Chapter 2 Contents

The case for career development and its contributions to improving employee engagement is now quite clear. In an online survey conducted in October 2007 by ASTD (American Society of Training & Development) in conjunction with Dale Carnegie and Associates and the Institute for Corporate Productivity (i4cp), over 750 learning, HR, and business executives and other leaders provided insights on their organizations’ practices related to engagement among their workers. According to the survey, “The respondents agreed that learning plays a key role in shaping engagement, and they ranked learning activities high among the processes they now use—or should use—to engage their employees.... Respondents reported on the impact of the learning function on employee engagement when asked about the factors that influenced engagement in their organizations. Quality of workplace learning opportunities ranked first among respondents from all organizations. Learning through stretch assignments and frequency and breadth of learning opportunities also were highly rated factors influencing engagement.”1

It is striking that there is still an imbalance between what management thinks satisfies employees—and therefore actions organizations take to create a working environment—and what employees actually want. One might be quick to jump to the conclusion that money is the prime motivator for employee satisfaction. After all, cash is king, right? In fact, in the late 1990s, the Society for Human Resources Management (SHRM) polled its members to better understand retention factors. Survey results showed that 89% of respondents said the biggest threat to retention was “higher salaries offered by other organizations.”2 But if this is explored further, there is evidence that disputes this belief, even from writings from as early as the 1940s and 50s that sought to analyze and understand human motivation.

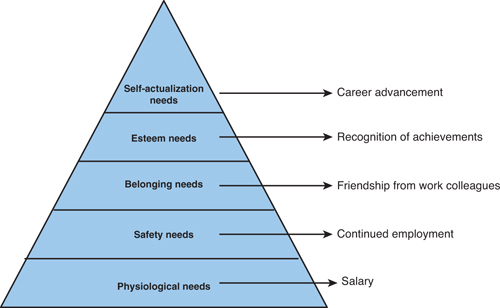

If we explore some of the early work of both Abraham Maslow and Frederick Herzberg, both professors of psychology, their theories of motivation provide insight into employee behavior. In 1954, Abraham Maslow published a volume of articles and papers under the title Motivation and Personality. His research and work established a hierarchy based on basic human needs and how this hierarchy would contribute to our understanding of motivation. He discussed these basic needs and their relationship to one another in what became known as Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs.”3

In Maslow’s theory, human needs are arranged in a hierarchy of importance. Needs emerge only when higher priority needs have been satisfied. By the same token, satisfied needs no longer influence behavior. This point seems worth stressing to managers and administrators, who often mistakenly assume that money and other tangible incentives are the only cures for morale and productivity problems. It may be, however, that the need to participate, to be recognized, to be creative, and to experience a sense of worth are better motivators in an affluent society, where many have already achieved an acceptable measure of freedom from hunger and threats to security and personal safety and are now driven by higher-order psychological needs.4

Maslow’s theory is often depicted as a triangle, where the basic needs appear on the bottom of the triangle and require fulfillment before the next need is met. Figure 2.15 reflects this hierarchy of needs. If this theory is applied to the workplace, the figure shows how management could provide a working environment that satisfies from the very basic needs to self-actualization. It could be argued that fulfilling self-actualization needs comes from within the person, whether that is by seeking employment in an area that one is passionate about or continuing to grow in one’s career. Managers can then create an environment for employees in which even the needs that sit on the highest point of the triangle are met by providing challenging work assignments and an opportunity for career advancement.

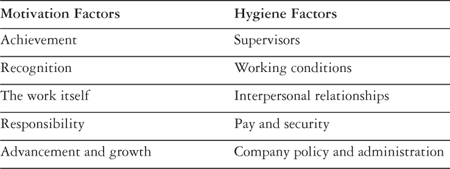

Another theory of motivation emerged a few years later; Frederick Herzberg developed the “two-factor theory” and in 1959 published his findings in a book entitled The Motivation to Work. He and a research team interviewed 203 accountants and engineers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, about satisfiers and dissatisfiers at work. Herzberg found factors that caused satisfaction (motivators) were different from factors causing dissatisfaction (hygiene factors).6 Table 2.1 shows the two sets of factors that caused either satisfaction or dissatisfaction and affected employee morale and productivity. Motivation factors relate to the work itself such as challenging work and recognition and provide satisfaction that leads to better morale, whereas hygiene factors relate to the work environment such as job security and salary. Hygiene factors do not give positive satisfaction, however; rather, they cause dissatisfaction if they are missing. Hence management needs to ensure hygiene factors are present—but must also provide the environment for the employee to experience motivation factors such as job achievement or career advancement.

Although both of these theories have been challenged over the years for one reason or another, they provide insight into how employees are motivated and provide management a potential framework on which to base employee career development practices.

Fast-forward to the twenty-first century, and studies continue to debunk manager perception of money being a motivator for why employees remain with a company. One study, as mentioned earlier, showed that managers believe employees leave for more money. Research conducted by Leigh Branham, along with the Saratoga Institute’s surveys that included almost 20,000 workers from 18 industries and many other studies, dispute this belief. Branham says that this research revealed “that actually 80–90% of employees leave for reasons related not to money, but to the job, the manager, the culture, or work environment... These internal reasons (also known as ‘push’ factors, as opposed to ‘pull’ factors, such as better-paying outside opportunity) are within the power of the organization and the manager to control and change.”8

Branham, in his analysis of unpublished research of Saratoga Institute conducted from 1996 to 2003, looked for common denominators and grouped the reasons for leaving to determine root causes. According to Branham’s analysis:

In fact, the number one response to the question, Why did you leave? was “limited career growth or promotional opportunity” (16% of responses), indicating a lack of hope.10

By now, the reader might be asking—so what do I do as a leader in an organization to improve employee engagement and therefore increase business performance? In the next section of this chapter, we discuss how IBM has used career development as a way to engage employees and increase satisfaction. Specific programs that have been implemented and lessons learned are discussed.

IBM Corporation has not been immune to the phenomenon described so far in this chapter. However, by better understanding client needs, IBM has been able to develop a career framework, a structure that defines the capabilities employees need to provide value to their clients. This framework is supported by a career development process that provides guidance to employees on how to advance in their careers. But this did not happen overnight. In fact, it was only after multiple studies and an evolution of interventions over a period of years that IBM was able to achieve this goal.

Internal surveys from 2003–2004 showed that some IBM employees felt they were not given an opportunity to improve their skills. Additionally, exit surveys revealed that perceived lack of career growth was one of the prime reasons employees voluntarily left the business. In 2004, IBM conducted a research project designed to better understand the challenges facing employees around their career development. Discussions with hundreds of IBM employees and managers, HR executives, review of existing IBM data such as exit surveys, and external benchmarking studies were reviewed. Additionally, input was obtained from an online global event called WorldJam, whereby thousands of IBM employees, managers, and executives collaborated for 72 hours and engaged in discussions on management effectiveness, workplace environment, and other matters. Collectively, input from these various studies and discussions led to a conclusion that IBM had a need for a “new day” in developing its people. These various studies pointed to five key themes that reflected the obstacles and critical success factors:11

• Career development is not viewed as a business priority.

• Challenging work assignments and opportunities are critical to employee development.

• Development tools are disconnected and their value to the employee is not clear.

• Career and expertise development needs to be aligned with the business strategy.

• Career development is about human interaction.

The study uncovered a huge gap between the corporate view of career development and the employee experience. Employees felt that the business focus on attaining short-term results consistently compromised development plans and activities. Furthermore, findings suggested that while many best-of-breed development resources were already available in IBM, the key challenge was that of execution. The underlying conclusion was that business priorities get in the way of development. While management can improve development practices and continue to create award-winning learning programs, in the end, none of it will make any difference unless career development becomes a business priority and employees have the time and opportunity to stretch their skills and learn new ones.

This conclusion was later validated by a 2005 study, sponsored by senior executives. The objective of this study was to recommend a strategy and implementation plan for professional development that would help IBM achieve growth and innovation and help employees attain career growth and success in a fast-changing business environment.

Based on these research findings, IBM put forth a call to action for a new day for career development that would span several years of iterative development and implementation. The new day would require redefining the roles of the employee, manager, and IBM in developing its employees and would focus the company’s efforts on ensuring effective execution of development best practices. The overarching goal of the new day was to align IBM’s values and business agenda with the passion of its great workforce to provide value to the client. It was about responding to employees’ hunger to make a difference, to feel connected to IBM, to be recognized for their contributions, and to realize their potential. An engaged, challenged, and expert workforce would be the key to IBM’s growth and innovation.

The following represent some of the programs IBM put into place from 2005 through 2007 as part of the first phase of this transformation of career development:

• An overhaul to the content of the new employee orientation program that had been put in place two years earlier that consisted of a 2-day classroom training and subsequent e-learning activities.

• Introduction to a one-day career event, a highly interactive, live event designed to help IBM employees learn about resources and tools they can use to grow their skills and create an engaging and energetic working experience for themselves today and into the future.

• Introduction of a formal learning program that offers employees the ability to explore and participate in short-term, experienced-based learning activities available outside of the formal classroom or e-learning. It is about finding the best alternatives for personal career growth and development and then creating the optimal solution.

• Revitalization of mentoring as a way to develop skills and career development of employees.

• Developing a “one-stop-shop” website that would become the trusted source for all career development guidance and personalized learning recommendations.

Between the time the initial analysis began in 2004 through 2007, when these programs were fully deployed and functioning, IBM enjoyed a six-point gain in employee satisfaction on a periodic survey that asked employees about their satisfaction with their ability to improve their skills at IBM. While many factors could contribute to this gain, surely the significant career development programs put in place by management would have had a positive impact on employee perception—and reality.

In 2006, an IBM study conducted with clients and business partners to better understand how the company could better serve its clients revealed a need to ensure IBM employees have the appropriate skills required to provide value to the client. One of the major outcomes of this study was the need for a common career framework that could benefit all IBM employees. As a result, in 2007, IBM embarked upon an initiative to create an enterprise-wide career framework that would enable career advancement for employees. At the time of this writing, the career framework is in the process of being implemented across IBM in a phased deployment that will take several years to complete. It will ultimately support the majority of job roles across the company. This is described later in this chapter and at length in Chapter 6, “Building Employee and Organizational Capability.”

Do an Internet search on the words “career framework,” and you will find literally thousands of websites in which all types of organizations—large and small, public and private—have implemented a framework to guide employees in the development of their careers. The sites contain many common words and phrases, such as skills, competencies, training and learning, career path, career progression, succession planning, gaps in skills and competencies, capabilities, opportunities, and more. Some frameworks are targeted at ensuring employees have the critical skills needed to satisfy customer demand and/or to achieve organizational goals. Other frameworks tackle longer-range career progression challenges such as how employees cannot only serve organizational goals by growing their skills, but also how they can enrich their lives through developing their careers along a particular path or even by changing paths over time. Others view the career framework as an enabler for succession planning. The possibilities seem to be endless—and they are defined differently from organization to organization.

In this chapter, an overview of IBM’s new career framework is presented, which when fully implemented, will be the backbone for how employees progress in their careers. It is also a major component of IBM’s expertise management system. The framework will be supported by a structured career development process that all employees currently utilize. Subsequent chapters describe IBM’s current career development process in depth and show how it provides the appropriate guidance for employees to grow the expertise needed to perform their current and future job roles. In addition, throughout the book, we highlight where applicable, on-going changes to the current career development process based on a need for continuous improvement.

Various dictionaries provide numerous definitions for the noun “career,” however “pursuing one’s life work” is a common thread. According to Dictionary.com,12 a career takes on various meanings as a noun:

“an occupation or profession, esp. one requiring special training, followed as one’s lifework: He sought a career as a lawyer.”

“a person’s progress or general course of action through life or through a phase of life, as in some profession or undertaking: His career as a soldier ended with the armistice.”

“success in a profession, occupation, etc.”

Merriam-Webster.com13 offers similar definitions, such as:

“a field for or pursuit of a consecutive progressive achievement especially in public, professional, or business life <Washington’s career as a soldier>”

“a profession for which one trains and which is undertaken as a permanent calling <a career in medicine> <a career diplomat>”

At IBM, these traditional views of a career are changing. As the technology industry continues to expand at a rapid pace and clients’ IT environments become increasingly complex, today’s employees need to be more multi-faceted, with a varied and versatile set of skills developed over time. No longer can a career be looked at as something that is undertaken as a “permanent calling.”

In today’s business arena, technical aptitude alone may not always be sufficient. There is a requirement for people to widen their portfolios of job roles, skills, and experiences to be applied and recombined in numerous ways to fuel innovative business value.

According to Ranjay Gulati, who wrote in a Harvard Business Review article in May 2007, “Rather than highly specialized expertise, customer-focused solutions require employees to develop two kinds of skills: multi-domain skills (the ability to work with multiple products and services, which requires a deep understanding of customers’ needs) and boundary-spanning skills (the ability to forge connections across internal boundaries.)”14

Although a life-long career as a specialist in a particular area is still needed and valued, marketplace demands suggest that some segment of the employee population needs a wider breadth of skills. This may enable—and/or force—employees to switch career paths over time to complementary or totally different job roles where new skills must be continually learned.

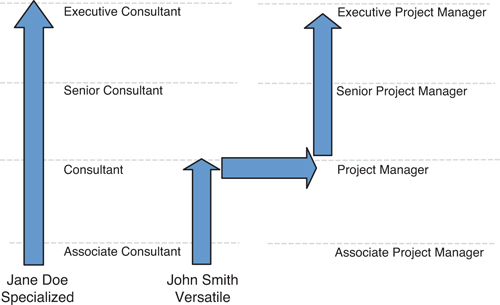

A career framework can facilitate both types of progression paths, whereby employees can grow in their careers either vertically in one area of specialization or horizontally across multiple areas of specialization over the course of time. Figure 2.2 shows this vertical and horizontal career progression.

Figure 2.2 depicts the career path of a consultant, Jane Doe, who starts out as an associate consultant and over time continues to grow her consulting capability through working on multiple engagments, increases her expertise via formal learning and on-the-job training, and takes on more responsibility as her job position matures. At the appropriate time, as she works her way up the consultant career ladder, has many client experiences, and receives various promotions over a number of years, Jane eventually becomes an executive consultant and is recognized as an expert in her field by not only her manager and peers, but by the client as well.

It should be noted that there is not necessarily a right or wrong time period for how long it may take an individual to go up the career ladder. It is determined by the individuals, their performance, the experiences they receive, the skills and capabilities they develop, and of course, the needs of the business. It may take many years to build the right capabilities needed to perform at the next level of any particular job role.

In contrast, John Smith, although he also starts out as an associate consultant, at some point he decides to branch out and leverage the project management skills he developed as a consultant by leading client engagements. He hears that project managers are in demand, given that the company is moving toward a project-based business. He also likes the planning aspects of the consulting role and wonders if he might be suited as a bona fide project manager. He explores this with his manager, who encourages John to think about becoming more versatile in building his capabilities. John subsequently decides he wants to change career paths and actually become a project manager. He works with his manager to put an individual development plan in place and identifies the additional skills and on-the-job experiences he needs to become competitive for a project manager job role.

John completes different learning activities to increase his skill in managing projects. He also works with his manager to be placed on the appropriate consulting projects to get increased experiential, on-the-job training. Once he has built more than just a beginning level of capability in managing projects, he finally takes on a project manager role, and over time, he gains sufficient expertise as a project manager and becomes competitive for promotion. Now John not only manages the project by tracking timelines, putting work breakdown structures in place, and managing to the project plan, but given his expertise as a consultant, he also gets involved with the consulting teams in expanding business opportunities. His more versatile set of capabilities has enabled him to expand beyond the expected career path and use more of the many skills he has acquired, rather than focusing specifically on his technical abilities.

Each career starts out in a similar fashion, but eventually these two individuals follow different paths that both result in success and fulfill a need for the company, the client, and the employee.

During the 1990s and early 2000s, changes occurred that would come to have a profound impact on IBM’s workforce. The explosion of the Internet and the ensuing services now needed by current and future clients to create complex networks resulted in a need for many new types of IT job roles and skills that hadn’t even been “invented” at the time. Expansion in emerging markets also created unique opportunities for different types of jobs, based on the skill base of varying countries. Lastly, IBM’s strategy of acquiring companies and their associated workforces and providing outsourcing services to companies—as well as hiring the outsourced company’s employees—created unique niches in “instantly acquired” job roles.

A more formal structure for developing expertise became paramount to attracting, developing, and retaining a skilled workforce of over 300,000 employees that were located in all corners of the globe. It’s hard to imagine the chaos that would result if there were no common language for defining job roles or the associated skills, or if each country or business unit “did its own thing,” based on what it thought was needed. There would be no way for employees to know about opportunities across the company, considerable waste and duplication of effort would be required to keep independent structures in place, and total solutions to meet client needs would not be feasible.

Around 1992, IBM created its first version of a “skills dictionary” or the beginning of a taxonomy that would define the skills needed by employees. Later that decade, IBM went on to create job roles based on this taxonomy and later expanded it globally across all business units. It has emerged into what is today, an expertise management system. This system guides the identification of the following elements:

• Competencies—The system starts with competencies that are needed by all employees, regardless of their job role, country, or status. These competencies or behaviors demonstrated by top performers are key indicators of success for high-performing employees and differentiate IBMers from competitor companies.

• Skills—Employees also focus on developing skills specific for their current roles or exploring skills needed for roles to which they aspire. Skills are fundamental to specific job roles and enable employees to perform their day-in, day-out tasks.

• Capabilities—As employees grow their competencies, become enabled, build skills, and gain new experiences, they develop capabilities that clients value.

Given the changing face of the IBM population, in 2003, IBM introduced competencies that were employee-focused. This was an expansion of existing competencies that were already focused on the development of leaders. There was a need to establish a common set of competencies that defined what it meant to be an IBM employee. These new competencies and associated behaviors were critical to achieving success for all IBM employees. They provided the foundation for professional growth and underscored company values, as well as established a common standard of high performance across the company. A robust curriculum of hundreds of learning activities were aligned to each of the competencies and their associated behaviors.

The competencies quickly became an underpinning of various HR processes, for example:

• The competencies are used to select new employees and as criteria for internal job movement. Various recruitment tools, including evaluation of job candidates, have incorporated the competencies as fundamental requirements of a successful employee at IBM, in addition to whatever technical or specialized skills a prospective candidate brings to the table.

• IBM’s performance management system has incorporated the competencies into its annual evaluation process and has had a significant impact on how results are achieved. Hence managers must consider an employee’s demonstration of the competencies when assessing year-end performance evaluations.

• The competencies have become a staple in pinpointing areas of focus that are important for individual development planning. Employees are encouraged to consider the competencies as they create their development goals and associated learning plans for achieving business performance.

Over time, the competencies have continued to show value to employees. Since the inception of the competencies in 2003, on average, over 300,000 learning activities in the competencies curriculum (classroom and e-learning activities) have been taken annually by IBM employees worldwide.

In a study conducted in June, 2004 by the IBM HR team, over 80 IBM employees across multiple business units participated and reported positive impact by increasing their competencies via the learning activities. Comments from participants include the following:15

“I was able to use what I learned in the Adaptability course in relation to recent organizational changes.”

“After taking How to Create Effective Presentations, I paid more attention when I created a presentation, which resulted in a more effective presentation.”

“I learned how to look at a project from the customer’s point of view. This approach made it easier to understand what they are asking for. Hopefully, this change will lead to better relationships and the ability to provide them with what they want.”

While the competencies have been extremely helpful to employees in defining the “basics” of what they need to demonstrate to be successful in their jobs, at the time of this writing, IBM is going through an extensive research study to determine whether the competencies are in line with the needs of today and tomorrow’s environment. The study may yield a new or refined set of competencies—or even a new structure for how the competencies are reflected in the career framework that is currently being deployed to employees.

IBM’s expertise taxonomy provides a standard framework and single set of terms so managers can develop and deploy resources consistently across all geographies and business units. This also allows IBM to satisfy developmental needs based on business unit and individual requirements.

The taxonomy is “housed” in a large database that identifies job roles and associated skills, creating common terms to describe what people do across the entire company. Although this may sound like a typical job description, the taxonomy provides the foundation for many other HR processes that enable having the right person, with the right skills, at the right time, place, and cost. This common language ensures consistency across various downstream IT applications that pull data from the taxonomy. For example, one of the various processes IBM uses is an assessment of employee skills. Applying the taxonomy to this type of assessment enables the company to determine what skills are in abundance, which skills are in need, and where those skills are located. This enables placement of employees with those skill sets on the appropriate projects or client engagements.

All employees need to grow and develop their skills. Hence, being able to identify skill gaps helps employees identify current skill needs and potential future job opportunities. It also provides the foundation for the types of learning activities an employee needs to progress in a chosen career.16

The career framework at IBM is an integral part of IBM’s expertise management system and provides the structure for how employees develop expertise over time; it also provides guidance for employees’ career progression. Furthermore, a structured career development process provides the various processes, tools, and career resources employees need to grow within the framework. The process also helps ensure that employees are growing the right skills as business strategies and needs change over time.

Capabilities are core skills that can be leveraged across the business. They are based on a multitude of experiences that IBM must deliver to enable client success. Capabilities focus on what’s needed to perform effectively, and they rely on a combination of applied knowledge, skills, abilities, and on-the-job experiences. Typically, multiple skills are required to demonstrate a level of proficiency in a particular capability. The level of achievement individuals attain in a particular capability is a composite of their education, skills, knowledge, and experience. To develop a capability, IBM employees must perform designated activities and achieve successful and consistent results that fulfill specified requirements as outlined in the capability level.17 The development of capabilities provides an avenue for advancement in one’s career by helping employees focus on the skills and experiences needed to advance within or move to other job roles in the company.

The career framework and supporting career development process provides guidance to employees on the variety of ways by which they can grow their careers in a linear or non-linear fashion (i.e. developing across many careers, resulting in development of multiple capabilities to varying levels). Generally, employees develop their careers at the job family level, for example, careers in Human Resources or Finance. As the career framework is deployed, employees will also be able to follow broader careers whereby employees leverage previously learned skills and apply them to new, but related job roles. For instance, a consultant is an expert in consulting methodology, however, because the consultant has to manage a consulting engagement, he also develops some level of project management skills. Over time, the consultant may desire a career change to become a project manager. He continues to grow his skills to eventually qualify for a new position as a project manager. The employee builds not only depth in a particular capability, but also breadth by growing capabilities in other complementary areas that enhance the individual’s ability to deliver client value. The process facilitates educated career advancement and encourages employees to progress in broader ways.18

Developing a varied set of capabilities is critical in IBM’s changing definition of career, where versatility in what one knows is becoming increasingly important to satisfying client demands. The primary objective is to help employees understand the core capabilities that IBM needs to deliver and what specifically employees need to do to make its clients successful. By establishing a common set of global capabilities with career milestones, the capabilities establish a common language that can facilitate career development and movement across the business.19

This chapter covered the importance of focusing on career development as an enabler of employee satisfaction and how development of a common career framework and supporting career development process can facilitate employee growth and progression in achieving career goals. Organizations would benefit from creating some form of framework that provides employees the ability to see the breadth of opportunities available to them and how they can grow by moving across job roles or business units. Other advantages include:

• Offers employees clear guidance on how to advance in their careers.

• Supplies a roadmap to developing capabilities that employees need not only to provide value to the client, but also to shape their own career paths over time.

• Provides clients with employees who have the capabilities to deliver “best in class,” seamless service.

• Aligns with company values and desired culture.

• Contributes to the company’s image in the marketplace and as a company to work for.

The career framework provides a model for how employees grow their expertise. A structured career development process provides the various resources employees need to advance their careers. In the next chapter, we introduce this supporting structure and provide the reader the opportunity to explore how some or all of these components may be suitable for their own organizations.

Endnotes

1Paradise, Andrew. “Learning Influences Engagement,” T+D magazine, January 2008, pp. 55–58.

2Gendron, Marie. “Keys to Retaining Your Best Managers in a Tight Job Market.” Harvard Management Update. No. U9806A. Copyright 1998 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College: All rights reserved.

3Adair, John. Leadership and Motivation: The Fifty-Fifty Rule and the Eight Key Principles of Motivating Others. Philadelphia, PA: Kogan Page U.S. 2006.

4“Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs,” Wikipedia.com, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maslow’s_hierarchy_of_needs.

5Graphic adapted from “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs,” Wikipedia.com, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maslow’s_hierarchy_of_needs.

6“Two-Factor Theory,” Wikipedia.com, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two_factor_theory.

7Herzberg, Frederick, “One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?” Harvard Business Review (September–October 1987), Reprint 87507, p. 8.

8Branham, Leigh with the cooperation of the Saratoga Institute™. The 7 Hidden Reasons Employees Leave: How to Recognize the Subtle Signs and Act Before It’s Too Late. New York: AMACOM Books, 2005, p. 3.

9Ibid, p. 19–20.

10Ibid, p. 20.

11People Development Team. “People Development at IBM: A New Day” presentation. December 17, 2004: p. 9.

14Gulati, Ranjay. “Silo Busting. How to Execute on the Promise of Customer Focus.” Harvard Business Review, May 2007: p. 105.

15IBM Learning Team in conjunction with Productivity Dynamics, Inc. IBM Competency. Level 3 Measurement Summary Report, June 2004: p. 9.

16IBM Intranet, Expertise Taxonomy website; “About Expertise Taxonomy.”

17Career Framework Team. Career Model Guide Playbook Chapter. March 24, 2008. p. 2–4.

18Career Framework Team. Career Model Guide. December 31, 2007: p. 48.

19Career Framework Team, March 24, 2008, op. cit. p. 2–4.