The 7-Step Premise Development Process

This is a process that you can use for your entire writing career; it will always tell you the truth, not necessarily what you want to hear.

In chapter one, I introduced the seven steps of the premise development process. Before you could even begin to use that process we had to lay down six foundation stones, the base concepts and ideas essential to fully realizing the potential of the premise line tool and the seven-step process designed to create that tool. Now, with those stones in place, however securely, we turn to what could be called the practicum section of this book. Here, in part two, you will have the opportunity to apply all those new ideas and concepts in a practical, methodological way to your story idea—even if you didn’t write out that idea in the first exercise.

The 7 Steps

“The 7-Step Premise Development Process” is designed to give you a repeatable, reliable, and validated methodology for consistently producing stories that will have narrative legs and survive the overall development process. As I said way back in chapter one, I cannot promise that every story idea you have will survive the process, but, in the end, you will be grateful for learning sooner rather than later that you may be running after the “wrong” story. Knowing upfront that you are working with a weak idea will save you countless hours, weeks, or months writing something that would ultimately lead you into the story flood plains. This process will empower you to be a conscious writer, i.e., give you the tools you need to make an informed and productive choice about where to put your creative energy, time, and money.

To that end, the “The 7-Step Premise Development Process” contains the following steps:

- Step 1: Determine If You Have a Story or a Situation

- Step 2: Map the Invisible Structure to the “Anatomy of a Premise Line” Template

- Step 3: Develop the First Pass of Your Premise Line

- Step 4: Determine If Your Premise Is High Concept

- Step 5: Develop the Log Line

- Step 6: Finalize the Premise Line

- Step 7: Premise and Idea Testing

You and I will take each of these steps and systematically work through the process with your story idea. Some steps are straightforward and uncomplicated, like “Step 3: Develop the First Pass of Your Premise Line.” But others require more detailed explanations and treatment, like “Step 4: Determine If Your Premise Is High Concept.” In many ways, this part of the book is an iterative loop, meaning that you can work through the seven steps and loop back through the steps many times, tweaking, honing, and refining your premise line. After the first time through, you will not have to repeat “Step 1: Determine If You Have a Story or a Situation,” because you will know whether you have a story or a situation, but you will repeat steps two through seven. I have known people, including myself, who have taken more than a month working through this seven-step process. In fact, I have had stories of my own that have taken me more than two months to refine into a workable premise line. I don’t say this to discourage you—quite the contrary. One of the first myths I’d like to help dispel for you is that premise work is not real writing. So, use this part of the book as your ultimate resource, and as with a great search engine, you can come back time and again and always discover something new.

Why a Process and Not Just a List of Steps?

It is important to realize that what you are learning here is a process and not just a list of seven steps. Lots of self-help books sell various steps as part of the hype to get you to buy the book: seven steps to perfect health, five steps to six-pack abs, three steps to finding the love of your life, and many more. This book promises seven steps to master premise and story development, and while I admit part of this is marketing copy, it is also literally the truth. But these seven steps are not just a numbered list of “to-dos.” The “7-Step Premise Development Process” is a process, not a list.

A list is simply that: do step one, do step two, and so on. You work through the list in a linear way and carry out each list item slavishly, in order, and you don’t skip any steps. You do the list as it’s written and the final result should be the promised deliverable (your six-pack abs or the love of your life). A process, however, is very different. A process is a sequence of interdependent and related procedures, often involving inputs (data fed into the system) and outputs (outcomes resulting from the processed data) at various points in the process, leading to some expected goal or result. For example, in this process, each step does not stand alone; rather, each builds, one upon the other. Step one feeds into step two, and step two provides the input data needed to execute step three, and so on. This interdependence and input-output relationship is essential in appreciating how working a process is different from just running a list of “to-dos.”

The other important aspect of a process is that at some point you will make it your own. A list is a list; it doesn’t change. It is always the list. Not so with a process. With a process, you learn the steps, work the process-procedures, become familiar with the inputs and outputs, and develop an intimacy with the inter-relatedness of all the parts. Over time, steps merge, combine, or seemingly disappear and you find that you can “skip over” whole steps because you just know what to do. It becomes so second nature that you don’t have to think about it; you just do it. You are not a slave to the list—in fact, you change the process by customizing it to your style of learning and your creative process. You don’t keep doing each step because Jeff Lyons (or anyone else) says you have to do it in any particular way. No, you make it your own; it becomes your process, and, as such, it becomes streamlined and self-engineered to facilitate your creativity, not some formulaic requirement dictated by a guru or teacher.

Listen to everyone, try everything—follow no one. You are your own guru.

When this happens, when you make the method yours, then you can say you have mastered the process. But this only comes with practice, practice, and more practice. If you just try it a couple times and then put this book up on a shelf or in a drawer, then you get what you pay for: a nice paperweight and not a powerful development tool.

Forms, Worksheets, and Samples

As you move through the seven steps, along the way I have provided some customized worksheets and development templates that you can use to facilitate knowledge transfer. You don’t have to use these tools, you can just wing it yourself and do your own thing, but I find that the documents I’ve provided do help focus the work and make the steps easier to visualize. You can access the forms, templates, and worksheets at the companion website set up for this book provided by the publisher. You can find the web URL address in Appendix C of this book. Once you go to the resource webpage, instructions for downloading documents will be available on the website. You will find the following forms and worksheets.

Premise Line Worksheet

This is the primary tool you will use to develop your story’s premise line. It guides you through the four clauses and maps the Invisible Structure to the four clauses of the “Anatomy of a Premise Line” template. This will be used in “Step 2: Map the Invisible Structure to the ‘Anatomy of a Premise Line’ Template.”

Log Line Worksheet

This is the tool that you can use to develop your log line and tagline. It asks you basic questions to help you identify the hook of your story. This will be used in “Step 5: Develop the Log Line.”

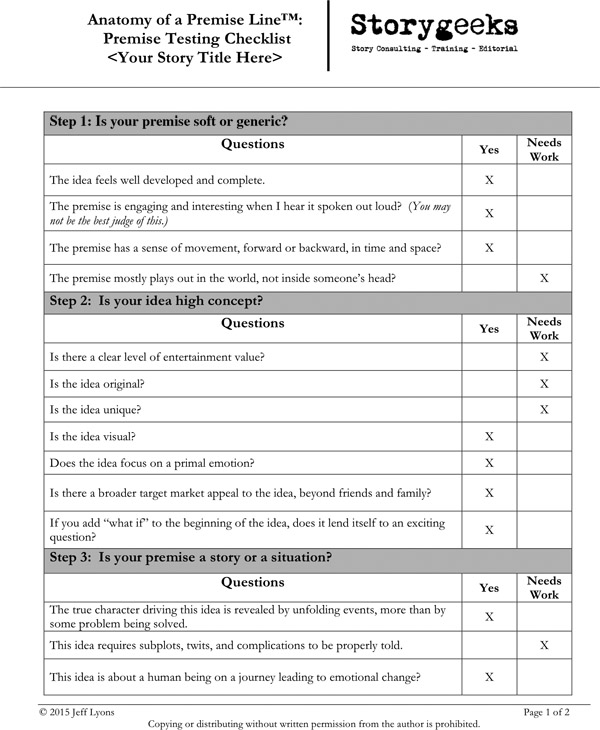

Premise Testing Checklist

This is the main tool that you can use to test your own premise ideas. This is a blank form that you can duplicate and use accordingly. This will be used in “Step 7: Premise and Idea Testing.”

Premise Testing Checklist Example

This is a fully filled-out premise testing checklist that illustrates how to properly fill in the boxes and add up the totals. This is also used in Step 7.

So—let’s begin.

Step 1: Determine If You Have a Story or a Situation

Why This Is the Hardest Step

Many of the steps of this seven-step process may feel hard at first, but of all the steps, this one is the hardest, because you have to tell yourself the truth. You know the five main criteria for assessing a situation versus a story, and once you work through each of those conditions you have to be willing to face the empirical results.

Does your story idea present a puzzle, mystery, or problem that is all about solving the problem and almost devoid of revealing your protagonist’s growth as a person? Is your protagonist challenged to almost exclusively out-think, out-maneuver, or out-fox the opposition, and not to change himself or herself? Are all of the reversals, complications, and subplots designed to complicate the problem and create more obstacles to be overcome, rather than open windows into character motivation? Does your protagonist end up in essentially the same emotional space at the end of the story as at the beginning? And is your protagonist grappling more with a shallow, personal psychological demon like booze or ADHD, rather than struggling to heal a profound moral component that drives all core dramatic action?

Take time with all of these five conditions and go over them carefully with impeccable attention. Don’t rush. If you end up with a situation and not a story, tell yourself the truth; it is only then that you can make an informed and proactive creative decision about how to proceed. If you have a situation and you move forward as if you have a story, then you will end up getting lost in the story flood plain. You will end up doing what I talked about in chapter three—losing your way and then backing into your story to find the right path forward. This is not the end of the world, but it is not a place you have to end up. As I’ve said before, this step is your first canary in that story coal mine. If it is lying dead on the bottom of the birdcage, you might want to start backing out of the cave. But, even if the canary dies, it doesn’t mean the idea has to. Remember, situations can be fun, entertaining, and financially profitable at the box office (and in print). Just tell yourself the truth about what it is you are dealing with—a story or a situation—and then you can make the best development choices.

The Whistles and Bells Test

The whistles and bells test is a quick test you can carry out whenever you get the inspirational flash of a new story idea. It is a simple, cut-to-the-chase technique that can quickly give you a sense of whether you have a story or a situation. It is not a substitute for learning the difference between a story and a situation, or for working through the full premise development process, but over time, with a lot of practice, you can hone a kind of sixth sense for the presence of a story. Here’s how you do it:

- Take your idea and get rid of all the whistles and bells. Get rid of all the car chases, all the robots, all the aliens, all the quirky set pieces; everything that you think is cool or that makes your script special and unique. Strip out all the flash-bang and glitz.

- Ask the question, “What is the story?”

- Wait and see what comes. If you have a story you will get a gestalt impression, almost immediately, of something like the following:

- This is a story about a man who has to learn how to love.

- This is a mother-daughter story about the meaning of loyalty.

- This is about a guy who will die if he doesn’t learn how to forgive himself for the past.

The test is especially useful with genre stories (mystery, horror, action-adventure, romance, etc.). For example, if you have a murder mystery, take away the murder and the mystery elements and than ask yourself if the story can still support itself without these two elements. If it is a story and not a situation, then you will still have a sense of the story (the human experience) even without the presence of the murder mystery.

Don’t look for lots of story details. Look for the big-picture sense of the thing: the protagonist and the main issue they face. You may get a clear picture of the opponent or core relationship too, but if you have a story you will get a gestalt sense of the hero-heroine and the core issue. The whistles and bells (action, adventure, mystery, etc.) are just noise, so when you get rid of them—if you have a story—it will hold up and shine through. A situation will just leave you with an action line or a puzzle-mystery to be solved. If you get a statement in your head similar to the three bullet points above, then you know you are on the right track and you can have even more confidence moving forward with the premise process. The “Whistles and Bells Test” is a powerful and easy technique that, when mastered, can develop your story senses to a fine edge.

Examples of Situations

All Is Lost (2013, Lionsgate):

Scenario: A lone sailor’s (Robert Redford) small boat is rammed at sea by a cargo container and he must survive the elements and his own mishaps in an effort not to lose hope.

Structures Missing: No moral component, no core relationship, no opposition (no, the sea is not the opposition, it is the story context—inanimate objects can’t be opponents).

Analysis: The story is about a guy battling himself to not lose the will to live in the face of overwhelming odds. This is a classic man-against-nature story, which is always a man-against-himself story. While these can be entertaining and engaging, they are almost always dramatically shallow and one-note. The sailor (unnamed in the story) is fighting for his life, but the message is more about “never give up,” which is also the tagline for the film. The main character does not give up, but he does give in and gives himself over to his fate, only to be rescued in the final seconds of the film—thus proving all is not lost. The entire film is a puzzle-problem scenario that tests the mettle of the hero, but it is more about problem solving than character development. We learn nothing about this man, other than that he is all too human.

Godzilla (2014, Warner Bros.):

Scenario: A scientist (Bryan Cranston) who thinks he has discovered the true cause of a horrible disaster in Japan convinces his estranged son, Ford (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), to help him investigate. The father dies when his theories are verified and two MUTOs (Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organisms) begin a rampage of destruction. Godzilla, the MUTOs’ only natural predator, reappears after being thought long dead, and proceeds to hunt his natural prey, while Ford uses his special ordinance skill set to disarm a nuclear bomb that is meant to kill the MUTOs, but which also threatens to destroy San Francisco. Ford explodes the bomb safely away from the city, which kills the MUTOs’ nest, and helps Godzilla get the upper hand in his own fight with the other monsters. Everyone is saved, and Godzilla goes back into the sea, presumably to arise again when nature calls him to save the day.

Structures Missing: No moral component, no core relationship (after father dies).

Analysis: This film follows in the tradition of the original, as a 1950s “B” monster movie. The father-son story promised some human depth, but was cut short with the father’s demise, and Ford’s “disarm the bomb” storyline only tangentially related to Godzilla; the real threat were the MUTOs. Ford started off as a promising character, as he grappled with his eccentric father, but then degraded into a typical “B” movie hero as he raced to rescue the city (and save his family). After the Cranston character died, there was no human relationship to drive the middle of the movie—or the hero—it was all monsters, all the time.

Use the five criteria to assess your story idea. Take your time. Assess whether you have a story or a situation, and then move forward. If you have a situation, then you can still do the next step, “Map the Invisible Structure to the ‘Anatomy of a Premise Line’,” but you will not have a meaningful constriction, moral component, or change. There is still benefit, however, in going through the mapping process to come to a strong, situational premise line.

Step 2: Map the Invisible Structure to the “Anatomy of a Premise Line” Template

Once you know you have a story, you can then map the Invisible Structure to the premise line template introduced in chapter five. If step one of the process is the hardest step, then step two is the longest. This step will benefit from you taking your time and having patience. I suggest you spend at least two weeks working through the Invisible Structure of your story idea. If you can allow yourself the discipline and fortitude to take even longer, that will be fantastic. I am usually of the school of thought that “less is more”—however, not in the case of this step of the process. In this case, “more is more.”

Apply the Map to Your Story Idea

If you did the first exercise in chapter one, then you have your first premise line written out. If you did not do the exercise, I suggest you go back and do it now. I’d like you to have some form of your premise written out so that you can do the mapping and have something concrete you can tweak and change as you repeat this step as many times as you need to. Take your story idea and do the following:

- Let your idea roll around in your head, and as you do, look over the seven components of the Invisible Structure (character, constriction, desire, relationship, resistance, adventure, and change).

- Read over your premise the way you have it written down and begin to look for each of the seven components in your writing. They will often jump out at you as single words, or more likely as phrases in the sentences. Write them down on a separate piece of paper to easily identify them. Repeat this as many times as you need to in order to get a solid feeling that you have found all the structure pieces obviously present in the writing.

- Now write down the missing pieces of the Invisible Structure, if some are absent. Which components did not jump out at you? Which appear lost? Maybe they are lost, or maybe they exist between the lines, and you just have to tease them out a bit? Go over your premise one more time (or many times) to get a sense of which Invisible Structure components are truly absent and which are just hiding behind the subtext.

- Map your premise to the “Anatomy of a Premise Line” template. Use the “Premise Line Worksheet” accessible through the e-Resources/Companion website URL provided in Appendix C, or refer to the worksheet example supplied in Appendix A, “Worksheets and Forms.” Build each of the four clauses of your premise line (protagonist clause, team goal clause, opposition clause, and dénouement clause). If you don’t use any of the provided worksheets, then duplicate the example premise maps given below.

Repeat this as many times as you need to, until you have a premise line that reflects the seven components of your story’s Invisible Structure, as best it can. You don’t have to get this perfect—in fact, you won’t. The key to this second step of the process is to listen for the structure talking to you, because it will “talk” to you as you work through the mapping. The pieces of the Invisible Structure that are clearly present will stand out, and the missing or hidden pieces will slowly make themselves known as you play with the language and rearrange sentences, manipulate phrases, and have fun with the wording. If you need to go back and review chapter five, “The Power of the Premise Line,” to re-familiarize yourself with each clause and its internal structure, then please do so. When you’re ready, follow the worksheet and write out your clauses as best you can. It helps to put the Invisible Structure elements of each clause in bold or underline so that you can visually identify them in the writing, thus assuring yourself that you are including the key structure pieces you need for each clause.

Be meticulous in the mechanics of the mapping process, but also be fluid and flexible in the creative writing taking place. This will be work, and can frustrate and challenge you. But, as I pointed out early in this book, it is better to sweat, strain, and work hard at this phase of the development process—before you have written a hundred or more pages of your script—than to write, write, write and find yourself lost in the story woods.

And don’t be discouraged if this step takes more time than you think it should take. Step two is the longest step of the process and juggles all the concepts you learned in part one. It is complex, but complexity breeds ease, not struggle. It may not feel that way as you work through the mapping, but you will see the truth of this when you come out the other side.

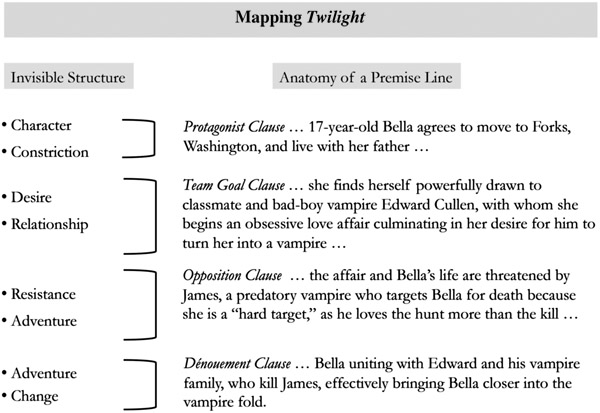

Three Test Cases

Use the following three films as guides to your own mapping process. Notice how the four clauses for each premise line are mapped to specific language reflecting the narrative of each story, and how that narrative, in turn, reflects back on the Invisible Structure. These are good examples that can help you visualize how your story might look after it is mapped.

Three Test Cases

Figure Pt2.1 Twilight (2008) Novel by Stephenie Meyer, Screenplay by Melissa Rosenberg.

Final Premise Line:

When 17-year-old Bella agrees to move to Forks, Washington, and live with her estranged dad, she finds herself powerfully drawn to classmate and bad-boy vampire Edward Cullen, with whom she begins an obsessive love affair culminating in her desire to be turned into a vampire so that they can be together forever, until the affair, and Bella’s life, are threatened by James, a predatory vampire who targets Bella for death because she is a “hard target,” and he loves the hunt more than the kill. This leads Bella to unite with Edward and his vampire family, who kill James, effectively bringing Bella closer into the vampire fold.

Note: This premise “line” demonstrates how two sentences can be used, and this works just fine. However, try for a single sentence, as this forces you to cut and kill your darlings. Definitely avoid more than two sentences.

Figure Pt2.2The Godfather (1972) Novel by Mario Puzo, Screenplay by Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola.

Final Premise Line:

The “innocent,” youngest son of a powerful mafia Godfather discovers his beloved father has been shot as part of a turf war, and agrees to join with older brother Sonny and step-brother Tom to exact revenge to re-establish the family’s honor and reclaim his own place within the family; when his ruthless need to keep his family safe emerges, causing Sonny and Tom to question his methods, distrust from his wife, and escalation of an already out-of-control war with the other mafia families; leading to Sonny’s death, his wife’s increased fear about what kind of man she’s married, a bloody and final end to the war, and his own dark metamorphosis into the new Godfather.

Note: This premise line demonstrates that a sentence may be very long, but can be written using proper grammar and punctuation as a single sentence. William Faulkner wrote this way and won a Nobel Prize (meaning he wrote long sentences with compound punctuation and many clauses), so don’t be put off by a complex sentence structure. The semicolon can be your friend; learn how to use it properly.

Figure Pt2.3 The Great Gatsby (2013) Novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Screenplay by Baz Luhrmann and Craig Pearce.

Final Premise Line:

When Nick Carraway, an ambitious Midwestern trader, leaves home to make his fortune amid the glamour of Long Island’s Nouveau riche, he attempts to solidify his standing among moneyed society by befriending Jay Gatsby, Nick’s rich and dissolute neighbor, and finds himself recruited by Gatsby to help rekindle an old romance with Daisy, Nick’s East Egg cousin; Nick finds himself caught in the middle of Gatsby’s romantic pursuit of Daisy, Daisy’s husband Tom’s affair with Myrtle, and Nick’s own contentious friendship with an ever erratic Gatsby, resulting in Myrtle’s death, Gatsby’s murder, ruined lives, and Nick’s ultimate rejection of the American Dream.

Note: This premise line demonstrates that you can change some of your wording in the final premise line so that each of the clauses don’t have to be slavishly followed word for word. In the Gatsby final premise line, I revised some of the text so that it captures the same effect, but reads a bit better than the individual clauses. Let yourself be flexible in how you render your final premise line. Let the mapping process act as the heavy lifting, and then refine or alter as you see fit for the final pass. Remember, this isn’t about being a mindless drone and doing the steps the way some guru tells you to—including me—do this the way you need to get results.

Step 3: Develop the First Pass of Your Premise Line

Now that you have worked through step two, you should have a fairly good map of the structure of your story in the form of the four clauses. They may be rough and grammatically awkward—that’s fine. Now is the time to refine and improve the narrative flow of your raw clauses. Use the map as your guide. This is the step that takes the output from step two and turns it into a narrative. Take some serious time with this step—don’t be rushed. Here is a basic approach that might help in the refining process:

- Don’t worry about having this be one sentence at this point. Write out each of the clauses as separate sentences, if that’s what feels right. You can condense and edit later.

- Literally mark up your writing and identify all the Invisible Structure pieces. If you are working off a computer screen, then highlight the seven components in a bright color. They may be single words or phrases, but look for them and mark them so you can physically see them in the text. If you have a print-out, mark up the copy accordingly. The idea here is to validate that you have the structure pieces in place.

- Once you have as many of the pieces in place as you can identify, start to rewrite the text with an eye toward killing your darlings; meaning, get rid of the adverbs, adjectives, and all the colorful and superfluous language that you think is clever or even “necessary” writing, but that doesn’t really tell the story. Here is an example of what I mean:

Text with lots of “Darlings” to kill:

Belfast, Ireland, 1967—When heavyweight contender Mickey Kerry, obsessed with becoming the Northern Ireland Area Champion, is approached by the reigning champ, Barney Wilson, for a title fight, Mickey hides the news, as well as his terminal illness, from his blond-haired, blue-eyed wife Jane, knowing full well that this fight is his last chance at the championship title—and the only hope for keeping his family from becoming homeless and penniless. Mickey teams up with Ben, his boxing manager, to secretly prepare for the Wilson fight, setting up a training camp and working secretly with Barney Wilson’s team to better prepare himself for the battle, a battle Mickey fully expects will kill him. At the same time, Mickey tries to set Jane up in her “dream business,” to prepare her for a life without him. Jane discovers he’s lying about the Wilson fight and kicks him out, turning then to a potential suitor, Inis, a local cop and “normal guy,” the kind of guy Jane had hoped Mickey would become someday. Inis is ready to step in and replace Mickey. Mickey loses the Wilson fight, and all his dreams, and in desperation arranges a winner-take-all fight with his worst nemesis, Rufus O’Reily, a fight that Mickey wins—thus winning back Jane and saving his family from ruin. He finally succumbs to his illness on Boxing Day, 1967, but not until after showing Jane the new store he bought her with his O’Reily winnings and spending the best Christmas of his life with his family.

Analysis:

As you can see, this premise has six sentences and lots of “value-added” language that could be considered fluff. But this is a great example of what your first-pass premise line might look like. Don’t worry about the early passes, they will all look and sound like this: long, flowery, and a bit overwritten. This is what you want. Once you know you have all the components of the Invisible Structure present, then you can start pulling out all the extraneous text and refining your language down to essential clauses. As I keep emphasizing, this may take time—lots of time. Take that time and let that be okay; it’s part of the process. Eventually, you will cut your premise down to a single sentence, or maybe two. In this case, the final result is spliced together with punctuation—not the best stylistic technique—but it’s still grammatically correct. One of Faulkner’s sentences from his novel Absalom, Absalom clocked in at 1,288 words. So, don’t worry if your sentence is long and a bit unwieldy—concern yourself with how smoothly it reads and what it says.

Text with the “Darlings” cut out:

Heavyweight contender Mickey Kerry, obsessed with becoming world champ, is approached by reigning champ Barney Wilson for a title fight and joins with Ben, his manager, to secretly prepare for the fight of his life, hiding the truth of his terminal illness from everyone, while trying to set his wife Jane up in her dream storefront; when Jane discovers Mickey’s scheme and kicks him out, she turns to a potential suitor, Inis, who is ready to step in and replace Mickey. When Mickey loses the Wilson fight, he is exposed as a liar, and in desperation arranges a winner-take-all bout with his worst nemesis, knowing it will lead to his death—he wins the fight, wins back Jane, and saves his family from ruin—only to succumb to his illness on Boxing Day, 1967, after spending the best Christmas of his life with his family.

Analysis:

As you can see, this version has only two sentences and is cut down to just the essentials needed to tell the story. We will use this same storyline in the next chapter as part of our synopsis-writing exercise, and you will see the premise line expand a bit to accommodate more of the story. The example here is meant to illustrate just how much you can cut from most prose and still retain your intent and the story’s integrity. “Killing your darlings” is a necessary craft skill every writer needs to learn, and one of the hardest to execute (no pun intended).

The premise line is for you foremost and for others secondarily. It is your lifeline as a writer, so make sure it speaks to you as a writing tool. If it speaks to you, then it will speak to others.

Step 4: Determine If Your Premise Is High Concept

At this point in the process we have defined your premise: we have broken it down to reveal your story’s Invisible Structure and validated that structure to demonstrate that you do, in fact, have a story and not something else—and you have settled on, at least preliminarily, your first premise line. Now it is important to understand what kind of premise you are working with: is it high concept or soft?

The obvious question you are probably asking at this point is, “I have a working premise—I’m happy! Who cares what kind of premise it is?” And that is a good question, a very understandable question, especially considering all the good work you’ve done to get a premise line. So, allow me to list exactly who will care a great deal about this issue:

- Literary, film, and television agencies

- Story development executives at production companies

- Movie studio creative executives

- TV network executives

- Independent film and television producers

- Film distributors and foreign sales agents

- Story department gatekeepers (readers, story analysts, story consultants)

- Essentially anyone and everyone that will be involved in marketing and selling your screenplay in the world marketplace

A lot of people will care what kind of premise you have. This concern affects you creatively, but it also affects your professional bottom line. In a moment, we will look specifically at what high concept means in the context of developing a story, but the essential point here is that the kind of premise you have is not so much a creative writing problem as it is a business issue. High concept sells scripts and novels, and gets movies made. Soft premises have a harder time getting optioned or sold, because marketing departments at movie studios have a difficult time conceptualizing effective sales campaigns, or identifying clear target markets for soft story ideas. They love high-concept ideas; those they can sell with gusto.

Screenwriters understand this better than novelists because the idea of high concept is endemic to the screenwriting trade. The term is part of the entertainment industry lexicon, even though few actually know what it really means. The stronger the high concept, the more likely a writer will get a pitch meeting or break through the gatekeepers at a production company or studio. But the same is true for novelists. There is a reason why Stephen King sells more books every year than most other novelists, and it has nothing to do with any perceived literary qualities of respective writing styles. Stephen King sells more books because he is a terrific prose writer and has mastered the art of the high-concept genre novel. He has found that magic balance between creating a piece of prose literature and commercial publishing.

Which Is Better: High Concept or Soft Concept?

If high concept translates into more sales, then high-concept premises must be better than soft premises—right? Wrong. The objective is not to make some judgmental assessment of right or wrong, better or worse, or to suggest some hierarchy of artistic worth. The point is simply that there is an economic reality to writing screenplays; what’s the point of writing if no one ever reads (or sees) your work? I suppose there are some who write for themselves and who put all their writing safely away in a drawer each night, and who could care less if the world knows about them, but these are the exceptions, not the rule. Writers write to be read, and more people will read your stuff if it is high concept.

The value here for a writer lies in knowing, before they send their work out into the world, what kind of premise they have so that they can appropriately respond to the business of being a writer and prepare themselves accordingly. For example, you wouldn’t want to send that horror-slasher script to Woody Allen’s production company, or conversely, send that introspective study in psychological angst to Twisted Pictures (Saw, Saw II-VI, Saw 3D). Rather, you will know ahead of the game that the horror-slasher script has a huge and specific target audience and a long list of genre-specific producers who will be interested, and the introspective angst script will probably have a small, niche market, so there is no point in expecting a bidding war to break out with the major studios (could happen, but probably not). Knowing your premise type helps make you a savvy entrepreneur and sets real anticipation and expectation for your post-writing job of being a writing brand and a professional.

It is important to understand that there is no market for screenplays outside of the established acquisition channels. What this means is that if you can’t sell your screenplay to a production company, or directly to a studio or network, you’re mostly done. I say “mostly” because there are distribution channels available now that were not available several years ago, like streaming video and web series production. But streaming video is more and more controlled by the large media companies, and unless you can self-finance a web show of your own, you are going to come up against the same obstacles and gatekeepers as in the “old” channels. The bottom line is: there will be no one publishing an anthology of the Best Unproduced, First-Time Screenplays anytime soon. At least novelists can self-publish, if their work goes “nowhere”—i.e., they can’t find a traditional publisher (or not). There is a “somewhere” they can go to find creative satisfaction and an audience: the Internet. Not so for screenwriters. As I often say, the beaches of Malibu are littered with the bodies of first-time screenwriters, because there is no market for physical screenplays. Consequently, knowing whether your premise is high concept or soft is not just a nice thing to know. It is an essential thing to know, as it helps you set your course and your commercial sights appropriately. As a screenwriter you won’t get many chances to break through the gatekeepers, so when it finally happens, you want your best presentation and your strongest high concept possible.

In order to know how to set your sights, you have to know the difference between the two types of premises. What does it mean for a premise to be high concept or soft? First, let’s look at what it means for a story to be high concept, then we’ll look at how this contrasts to a soft premise, and then we’ll talk about what you do as a writer after you know what type of premise you are working with.

What Is a High-Concept Premise?

As writers, we have all come up against the agent, producer, executive, or fellow writer who, when asked to give feedback on our story, retorts, “Yeah, good idea, but it needs to pop more. There’s no high concept.” But when asked to explain themselves and define their terms, these same people only deliver clichés:

- It’s your story’s hook.

- It’s what’s fun about your story.

- It’s your story’s heart.

- It’s your story as a movie one-sheet.

- It’s the essence of your premise.

- And so on…

While many of these speak to the idea of a high concept, none of them really explains what a high-concept idea is. “High concept” has become a term d’art that everyone uses and that almost no one really understands.

High concept applies to any idea: motorcycle design, toothpaste, cooking, comic books, novels, and movies—the list is endless. High concept is about essence, that visceral thing that grabs you by the scruff of the neck and doesn’t let go. From a writing perspective, a story idea that is high concept captures the reader’s or viewer’s imagination, excites their senses, gets them asking “what if,” and sparks them to start imagining the story even before they have read a word. More than this, a high-concept idea can be thought of as a cluster of qualities that exist on a continuum, rather than as a single trait that a story possesses or doesn’t possess. When these qualities are working together they convey the meaning of high concept for an idea in the same way personality qualities help define the individuality of a person.

There is an elegant construct that I think both defines the term “high concept” and that also gives you a tool for testing your ideas to quickly see if there is a high-concept component present in any premise idea: “The 7 Components of a High-Concept Premise.”

The 7 Components of a High-Concept Premise

The following are the seven components of any high-concept idea:

- High level of entertainment value

- High degree of originality

- High level of uniqueness (different than original)

- Highly visual

- Possesses a clear emotional focus (root emotion)

- Targets a broad, general audience, or a large niche market

- Sparks a “what if” question

Let’s look at each of these to get a better idea of what they mean.

High Level of Entertainment Value

This can be elusive. Defining “entertainment value” is like trying to define pornography; it’s in the eye of the beholder. Simply put, you know if something is entertaining if it holds your attention and sparks your imagination. If you are distracted easily from the idea or interested purely on an intellectual basis, then it is safe to say that the idea may be interesting, engaging, and curious, but not entertaining.

High Degree of Originality

What does it mean to be original? Some common words associated with originality are: fresh, new, innovative, novel (no, not a book). Think of originality as approach-centric. The idea may be centered in a familiar context, but the approach (original take) offered to get to that familiar context has never been used before.

So originality is more about finding new ways to present the familiar, rather than inventing something new from scratch.

Examples of Originality

- Dog Day Afternoon (1975, Warner Bros.):

- Familiar idea: A man robs a bank for money.

- Original take: A man robs a bank to get sex change for his transsexual lover and wins the hearts and minds of the people.

- Toute une vie (And Now My Love—1974, AVCO Emabssy Pictures):

- Conventional context: Boy meets girl.

- Unique take: We see all the generations that led to the boy and girl being born, their love affairs, lives, and all the things they experience that make them who they become as adults; the lovers don’t meet until the end of the movie.

- Frankenstein (1994, TriStar Pictures):

- Familiar idea: The evil monster terrorizes the humans.

- Original take: The monster and humans switch moral ground and the humans terrorize the monster.

High Level of Uniqueness

Whereas originality is about approach and fresh perspective, uniqueness is about being one-of-a-kind, first time, and incomparable. Being original can also involve uniqueness, but being unique transcends even originality. Sometimes this is achieved in the content or in the execution of a work. This often means taking a conventional context and rethinking it in a unique way.

Examples of Uniqueness

- Finnegans Wake (novel by James Joyce):

- Conventional context: Episodic, slice-of-life vignettes of HCE, ALP, and other characters.

- Unique take: One-of-a-kind writing style never before used in modern fiction.

- Sallie Gardner at a Gallop (1880, Eadweard Muybridge):

- Conventional context: No precedent.

- Unique take: Believed to be the first motion picture exhibition anywhere.

Highly Visual

High-concept ideas have a visual quality about them that is palpable. When you read or hear about a high-concept idea, your mind starts conjuring images and you literally see the idea unfold in your mind. This is why high-concept books make such good films when adapted. Books with cinematic imagery are almost always high-concept stories, like Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail, by Cheryl Strayed, and Gone Girl, by Gillian Flynn.

Possesses a Clear Emotional Focus

Like imagery, high-concept ideas spark emotion, but not just any emotion—usually it is a root emotion: fear, joy, hate, love, rage, etc. There is no wishy-washy emotional engagement of the reader. The involvement is strong, immediate, and intense.

Possesses Mass Audience Appeal

The idea appeals to an audience beyond friends and family. The target market is broad, diverse, and large. Some ideas are very niche, appealing to a specific demographic, but this is usually a large demographic. High-concept ideas are popular ideas, mass ideas, and often trendy ideas.

Usually Born from a “What if” Question

What if dinosaurs were cloned (Jurassic Park)? What if women stopped giving birth (Children of Men)? What if Martians invaded the Earth (War of the Worlds)? High-concept ideas are often posed first with a “what if” scenario and then the hook becomes clear. The hook is that part of the high concept that grabs the reader. It is often the one piece of the idea that is the original concept or the unique element. In the three examples just given, each of them has a clear hook that leads to a high-concept premise line.

As we will see later on when we cover premise testing, most ideas never have all seven components. Stories usually express their high concept along a continuum, meaning they may have two of the components, or five of the components. The more of them you can identify in your idea, the stronger the high concept. Having one quality out of seven does not mean you have a bad idea, it just means that you are closer to a soft premise than a high concept one. It is important that you know how to assess your premise idea. Knowing the kind of premise you have makes you knowledgeable, prepared, and fully conscious as a writer. You can take full ownership and responsibility for your work product, and any decisions you make with regard to the marketing and sale of your story idea will be fully transparent to you and consensual. This is a good thing; it only adds to your professionalism and helps build your confidence as an entrepreneur.

What Is a Soft-Generic Premise?

We’ve spent a long time talking about the high concept, so now let’s turn to the soft concept. What is a soft premise and how does it differ from a high concept one? As with the idea of high concept, a soft premise is often defined with clichés and generalities. When asked to define “soft premise,” proponents will often offer the following:

- It means there is little or no action.

- It means you have a “character” piece.

- It means you are dealing with internal, not external, action.

- It means your story doesn’t have a plot.

- It means your story is dull.

- And so on…

Once again, as with the conventional definitions for high concept, there is some truth to all of these conventional soft premise definitions, but none of them accurately describes the idea of a soft premise. Defining the soft premise can only have meaning in relation to the high concept. If you are missing the seven components of the high concept, then you are left with a soft premise. This is a “simple” reductionist approach that yields practical results. The weaker the high-concept premise is, the mushier the overall idea will feel. The less original, visual, or generic the premise idea, the more uninspired and “low-concept” the idea will play.

Every story is high concept to one degree or another—the question is to what degree. High concept exists on a continuum; it is not a single trait that is or is not present in a story. So, the more of the “7 Components of the High-Concept Premise” that are present, then the more high concept the idea. The fewer components present, the weaker the high concept.

As I said at the beginning of step one of this process (“Determine If You Have a Story or a Situation”), the premise line is your lifeline as a writer. Knowing you have a soft premise (by process of elimination of the “7 Components of the High-Concept Premise”) tells you a great deal about what may not be working in your idea. Even if you think the idea is fantastic, you may not always be the best judge. Consider the other side of this problem. “Soft” doesn’t mean the idea is bad, but sometimes realizing an idea is soft can help you realize the idea is, indeed, bad. Consider some premise lines that writers have given me for their screenplays:

- When a retired woman finds herself on a trip to Peru, she visits Inca historical sites and discovers the richness of past cultures.

- When a schoolteacher moves to a new town, he finds himself teaching a new subject that has never interested him, but when the students respond positively to his teaching, he decides to keep the class.

- When a grandmother turns one hundred, the family organizes a family reunion and the entire family gets together for the first time to celebrate.

- When a man plays golf for the first time he falls in love with the game and commits himself to a lifestyle of golf and recreation in order to master the sport.

These are not just boring good ideas; these are boring bad ideas. The above examples illustrate a circumstance where knowing what type of premise you have can be a major red flag tagging story problems you are developing at the premise level, which if not handled immediately will cause you days, weeks, or months of grief down the development road. The writers of each of these thought they had good ideas, until they applied the high-concept/soft premise analysis to their stories. All the other validation tools built into this process failed to register with them, but for some reason it all clicked when they typed their premise ideas.

The High-Concept / Log Line Worksheet Exercise

Using the “Log Line Worksheet” form in Appendix A (and available electronically on the e-Resources/Companion website URL found in Appendix C), fill in each of the seven components of any high-concept idea, as they pertain to your premise line. Don’t do the log line or tagline portions yet; those will be done in the next step of the process. Right now, focus on your story’s high concept and work with this form to identify as many of the high-concept components as you can for your story. If you do not use the provided worksheet, then do the work on your own using whatever method works for you. Hang on to the output from this step, as it will help you in the final step of the process when we cover premise and idea testing.

When you have a concrete technique like this one for assessing your premise type, as opposed to relying on tired, old clichés, you arm yourself with one more tool for the story development toolbox, and you bring yourself many steps closer to being a master of the premise development process. Soft or high-concept premise: knowing how to distinguish between both can pay off in terms of sales, but also in terms of saving precious writing blood, sweat, and tears during the development process.

Step 5: Develop the Log Line

Premise line in hand, or at least a version you feel is solid enough to work with, it is now time to create a log line for your story. The log line and premise line are often used interchangeably in the film and television worlds. Many people, including experienced producers and executives—and screenwriters—make little or no distinction between the two terms. Premise and log lines are, in fact, different things and provide different functions in the development process.

What Is a Log Line and Why Should You Care?

It was no accident that high concept was included here as step four, because to understand the log line you must first understand the meaning of high concept. The reason for this is the true nature of the log line:

The log line is your high concept stated in a single (short) sentence.

The log line is not your premise line. It is not related to the premise line in any way, beyond the connection it has to the same story the premise line is describing. The premise line is the entire core structure of your story in one sentence (or two)—often a complex and long sentence. But the log line captures a single component of your story: its high concept.

Remember, way back in chapter three, I talked about what happens when you get an idea for a new story. That big ball of undifferentiated information called the Invisible Structure drops in and you have that “aha” moment, and a story is born. Or at least you think a story is born. Then, you begin to unravel that Invisible Structure, piece by piece, to validate that you have a story and not a situation.

But, let us back up for a moment and revisit this idea of the “dropping in” of the story idea. When that story structure drops into your awareness, before you sense a story, before you sense any of the parts of the structure, something else happens in that moment that catches your breath and leaves you with that “aha” sensation. What happens is that you get an image in your mind that captures that sensation. This happens to everyone, not just writers, when they get an idea for anything new they are creating. The Invisible Structure of the idea drops in and immediately gives them a visual impression of the idea itself. Sometimes it is just a single image, sometimes it is a tableau of images creating a mini-movie, and sometimes the image is accompanied by a strong core emotion (love, fear, hate, shame, etc.). Regardless of how detailed the image, or how complex or simple, it excites you and sets you on fire to want to explore this new idea in earnest. This is your story’s hook. This is the thing that grabs you first, and then pulls you into the complexity under its surface. And if this hooked you, then it will hook an audience (or reader).

Just as with the story’s overall structure that must be captured and expressed in a usable and practical form (i.e., the premise line), so the hook/high concept needs to be captured and represented in a practical and usable form. That is the log line. The premise line is your story’s structure in a single sentence (or two), and the log line is your story’s hook captured in a short sentence. The log line holds that image and makes it accessible to others so they can share the same sense of excitement you had when the story dropped into you, but whereas you were compelled to go deeper under the surface, others will simply be hooked and compelled to read the script and make your movie.

How Do Premise Line and Log Line Work Together?

A natural question at this point is, “Why would I need a log line, when I have a working premise?” There are many reasons why a screenwriter needs a log line.

The log line accomplishes the following:

- It can lead you to the hook and entertainment value of your premise BEFORE you write your premise line.

- It can often help you develop the pitch-perfect, high-concept title (e.g., Jaws, Cowboys & Aliens).

- Producers will ask for one. The log line—not the premise line—is tailor-made for pitching. The log line is what ninety-nine percent of all producers or agents will ask for when you submit a query or trap them in an elevator to pitch your story. You don’t want to be unprepared.

- It validates your original moment of inspiration.

- The log line works with the premise line to help support the overall development process. Your log line and premise lines should fit together like a hand in a glove. They should not be different; meaning, they should have the same narrative tone, genre, and context.

Log Line Examples

- A monster shark terrorizes a small coastal town. [Jaws (1975), Peter Benchley, Carl Gottlieb]

- A cop battles über-thieves when they take over an office building. [Die Hard, novel Roderick Thorp, screenplay Jeb Stuart, Steven E. de Souza]

- A young boy discovers he’s a wizard and goes off to wizard school. [Harry Potter, J.K. Rowling]

- A man saves a pregnant woman in a world where women no longer give birth. [Children of Men, novel P.D. James, screenplay Alfonso Cuaron, Timothy Sexton, David Arata, Mark Fergus, Hawk Ostby]

Note: You may get the feeling that log lines sound a lot like situations—they are not. They are not stories or situations; they are log lines. They are the hook of your story in a short sentence, so don’t overthink this, or confuse them with premise lines, stories, and situations.

What Is a Tagline?

If log lines are the story’s hook, the tagline is the bait on the tip of the hook.

The tagline for any movie is pure hype. Taglines are advertising copy and nothing more. They will not help you write your premise line, but they will help catch the eye or ear of someone you might want to read your script or fund your movie. They can also look nice on the cover of your film’s novelization. Typically, you will not have to come up with this slick little piece of salesmanship, but sometimes it is worth writing on your own just to see what you come up with. Occasionally, it might help you find your way into the best idea for expressing your log line, playing a similar kick-starter role for the log line as the log line can for the premise line.

But, most often, this is not a critical piece of the process and can be considered value-added if you decide to conceive a tagline on your own. The more sales tools you have for your pitching effort, however, the better, so why not arm yourself with all the tools possible?

Tagline Examples

- Just when you thought it was safe to go back into the water. [Jaws (1975), Peter Benchley, Carl Gottlieb]

- In space, no one can hear you scream. [Alien (1979), Dan O’Bannon, Ronald Shusett]

- The trap is set. [Flytrap (2015), Stephen David Brooks]

- A romantic comedy. With zombies. [Shaun of the Dead (2004), Simon Pegg, Edgar Wright]

It should be no surprise to you that the higher the concept of a story, the stronger the tagline will be. Advertising loves high concept, and taglines are used with everything from toothpaste to Winnebagos. Sales is sales, and no one knows how to sell a widget better than the major film studios and television networks. Their marketing departments are geniuses when it comes to coming up with catchy and memorable taglines. To come up with your own taglines, just follow their example and you will find a great piece of bait.

The Log Line / Tagline Worksheet Exercise

Using the “Log Line Worksheet” form in Appendix A (and available electronically on the e-Resources/Companion website URL found in Appendix C), fill in the sections that apply to creating the tagline. If you do not use the provided worksheet, then do the work on your own using whatever method works for you. Hang on to the output from this step, as it will help you in the final step of the process when we cover premise and idea testing.

Step 6: Finalize the Premise Line

What Does Final Mean?

Are you ever really done with writing your premise line? You are never really done writing anything; you just decide to stop. At some point you just have to set goals, meet them, and then come to an end. What will happen with your premise line is that you will feel a physical sensation in your body, or have a strong emotional sense, or “hear” a voice in your head tell you that it’s time to stop. The premise line will feel balanced, alive, and will tell a story with an economy of words that will impress even you. You are now ready to move to the next phase of your development process and either start pages, or write a short synopsis or a long synopsis. Whatever you do—celebrate the moment. You have been through a long, hard slog, and you deserve to reap the rewards.

As you get into the writing process, post premise line, you will find yourself going back to it time and time again, checking your progress on the page with the story in your premise line. They may fall out of sync as you write. Perhaps you have gone off on a narrative tangent—no problem. Go back to the premise line and see where in the premise you need to come back to in order to maintain the through line. Or perhaps you go off on a story tangent and it feels right and true, and your premise line has fallen out of sync with your writing. This can happen. If it does, then rewrite the premise line to incorporate this more true story tangent. All it means is your premise line was wrong, so fix it and move on. This is how it goes over the course of the entire writing process. The premise will inform the writing, and the writing will inform he premise line. At some point they will just settle down and stay in sync; that’s when you know you are truly done with premise development. So, “final” is a relative term, not just for your screenplay as a final piece of writing, but also for your story’s premise. It is a work in progress as long as the work itself is in progress.

Step 7: Premise and Idea Testing

What Is Premise Testing and Why Should You Care?

Premise and idea testing are two things most writers don’t even think about. Here’s what they think about instead:

- They get an idea for a story.

- They start brainstorming scenes, characters, set pieces.

- They start writing pages.

- They write, write, write—then stop.

- They’re stuck—and the depression begins.

- They start to back into their story (see chapter three)—and realize the premise is off.

- They hire a story consultant, or script doctor, or get notes from someone they trust.

Invariably, if the consultant or editor knows what they’re doing, they bring the writer back to their core premise idea. The writer almost always has to start over with story fixes the consultant or editor suggested. If they know what they’re doing (they don’t always), then things move forward in a “correct” direction and the story is saved. But, the writer is often left with a lot of pages they can’t use—pages that are simply the legacy of lost time and creative effort.

Some say there is no such thing as wasted writing time; all writing is useful and helpful and better than not writing. I understand this sentiment, and it is a nice sentiment, but it is not true. I’ve worked with too many screenwriters, novelists, and producers, some of whom have wasted months or even years of writing time only because they didn’t know there was a craft solution to the problem of what I call “premature writing.”

Premise testing isn’t sexy, it isn’t creative, it isn’t artistically satisfying, and it will not bring you closer to your muse. But, what it will do is give you invaluable information about the state of your development process before you have committed countless hours to writing and script design. It is a pure exercise in marketing and product testing. Anyone who sells any product market tests that product. So, why not writers? Writers who have no interest in commercial success will find all this pointless. No problem. If you are writing for the pure joy of writing, and art for art’s sake, more power to you. But, if you are looking for work and maybe having a career as a professional screenwriter, then premise testing is a necessary skill you need to learn as an entrepreneur and businessperson.

It is in this spirit that I offer this practical tool that you can use to get objective and meaningful feedback about the potential of your story—before you write a first draft. As part of this week’s written assignments, you are being asked to fill out the “Premise Testing Checklist.” This checklist is designed to ask a series of questions to inform you about all things that make a book attractive to readers: commercialism, high concept, story vs. situation, etc.; all the things we’ve been discussing and exploring for the last two weeks. This checklist gives you a gestalt picture of the “appeal factor” of your story to your target audience, but more so it validates your premise, premise line, and the story idea itself.

Even if you couldn’t care less about commercial success, learning how to do this checklist will give you one more level of confidence that your book idea will work and actually have legs for the long haul of writing. This alone is enough of a reason to learn how to use this tool.

The key to using this to maximum effect, however, is that when you give it to third parties to fill out, you only give it to people who know what they’re talking about. Don’t give it to people who will tell you what you what to hear (like your mother—unless she’s an story editor at Paramount). Give the checklist to editors, other screenwriters, movie producers, writing teachers at local universities, or even hire story consultants to give you feedback. You need real advice and opinion. Only people who don’t know you well and who have no personal investment in the process will be able to give you that kind of feedback.

You may find that you have to explain some of the ideas behind high concept, story vs. situation, etc., but now you know those concepts and can explain them. You may be surprised how receptive people may be to learning new ideas from you. You may also be surprised how many people will respect the fact that you are asking for their feedback. If they want you to pay them for the privilege, then do it. It’s worth it (if they know what they’re doing with story). Their expertise is worth the price of admission. But, a lot of people will just say “okay” and help you. If you can only do friends and family, then go for it. But tell them to tell you the truth, not what you want to hear. Then take that feedback and use what you can, and discard what is not helpful. Go for objective feedback first; get knowledgeable writers and editorial people to help you.

How to Use the “Premise Testing Checklist”

The seven steps are as follows:

- Step 1: Determine if premise is soft.

- Step 2: Determine if premise is high concept.

- Step 3: Determine if it’s a story or a situation.

- Step 4: Does the log line work?

- Step 5: Does the tagline work?

- Step 6: Revise premise with any new insights; is it better? Worse?

- Step 7: Unit test your final premise line.

You can see that the seven steps all cover things we’ve explored and have used throughout the first two parts of this book. The two-page “Premise Testing Checklist” worksheet combines all that you’ve been using to develop your story idea.

The basic process unfolds as follows:

- Give the checklist to objective third parties and have them fill out steps one through six.

- Then give it to friends and family and have them do the same.

- Then, you answer both questions in step seven yourself.

- Add up all the checks in both columns and assess the outcomes.

The higher the “needs work” column number is, the more the message to you is “this needs more work.” Then you have to look at your responses and get a sense of where your respondents had common issues/checks. This can tell you a lot about where in the premise process you may need to go back and redesign the premise line. Your structure is off—this can tell you where to look.

Obviously, if you have more checks in the “yes” column than in the “needs work” column, then you are in good shape. It is still worth looking at the checklist responses for trends and patterns. You can learn a lot about what most appealed to respondents about your idea. And obviously, if your “yes” and “needs work” columns are about the same weight, then you have to look closely at where respondents checked their boxes to see what problems or strengths the respondents noted in common.

The bottom line here is that this checklist, and the process for getting it filled out, can be another assessment tool for you, giving you more feedback about your premise line and the story idea as an idea. As I said earlier, this may not be sexy and creative and artistic, but it is practical and useful and powerfully simple as a tool to help you know—before you start writing—that your premise idea will have legs strong enough to carry you (and your story) to the end.

![]()

Figure Pt2.4 Premise Testing Checklist Sample