5 Building Inclusive Leadership into the Company DNA

For at least half a decade before the Black Lives Matter movement came to the fore in the corporate sector, the smartest business leaders were talking about the importance of inclusive leadership—a concept I’ve defined here:

Inclusive leadership builds inclusive work environments, values diversity, and inspires individuals and teams to unlock their full potential by bringing their full selves, unique experiences, and perspectives to the organization.

Michael C. Bush, the CEO of the workplace-culture consulting firm Great Place to Work, has described a new breed of business executives who “transcend traditional leadership approaches that don’t keep up with today’s economic and political challenges. They embody emerging mindsets and skills like humility, empathy, and learning agility. They are the drivers of innovation and are setting the pace for the future of work.” Bush calls these executives for-all leaders.1 His description is right in line with the bold strategic vision that I talked about in the last chapter, the vision that has to come from the CEO and senior managers because only the leaders have the power to carry out big strategic changes in an organization. Once you’ve adopted the vision of an inclusive, for-all leader, however, the design you’ve created for a transformation must now be integrated into the workplace and embedded in the culture, values, performance, and incentive systems.

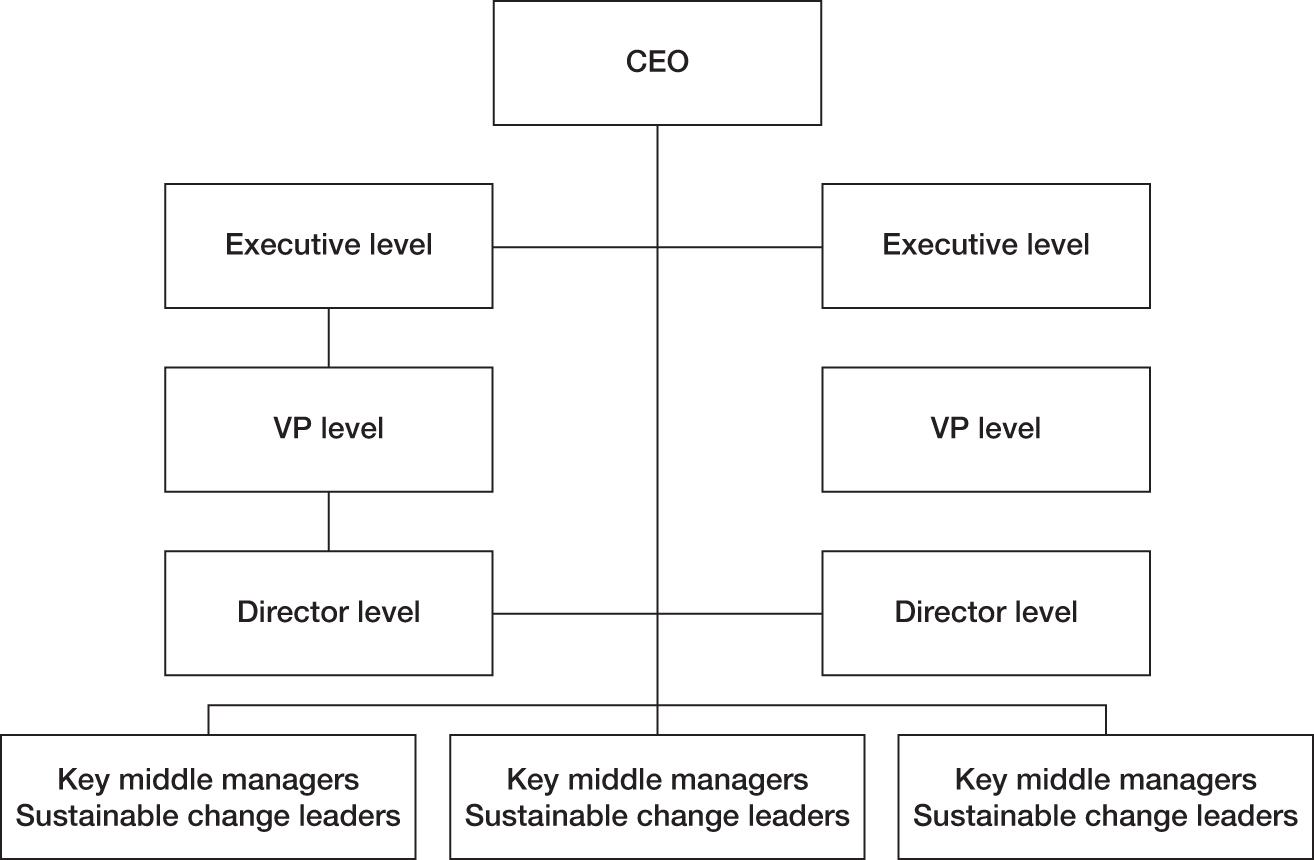

How do you instill inclusive leadership at every level? In my consulting practice, Culture Design Lab, when I talk to CEOs and other executives who want to bring about change, I ask them to draw a diagram of the organizational chart. This is a literal drawing, but I also ask them to describe the layers of management and how many people report directly to the senior-level managers, then the next level, and then the next. By diagramming your organization this way, you will find the key you need to unlock cultural transformation. (See figure 5-1.)

You look at these layers one by one because you’re seeking the answer to a crucial question: Who are the managers who have the largest number of employees reporting directly to them? In every organization, you’ll find that critical change lever somewhere in middle management. They’re the people most responsible for carrying out any new processes. They are also responsible for setting the career paths of others. At a supermarket chain, most of the workforce might report to district managers. At a restaurant chain, it’s usually the district or regional operating leaders who run a certain area. At a consumer-goods company, it will probably be the cross-functional leaders at a director level in sales, marketing, manufacturing, and technology. At a restaurant operation with several thousand locations and 100,000 employees you might have 150 middle managers. They are the people who are most responsible for the careers of the staff, so their actions and decisions have a powerful impact.

FIGURE 5-1

For-all leadership model: middle managers as catalysts for change

The key to driving sustainable change lies in reaching down the chain of command to the middle managers and giving them the tools and incentives to carry out the changes, because their domain is where most of the people in the organization reside.

In chapter 4, I talked about enlisting middle managers as your handpicked catalysts for change. You don’t have to bring in every middle manager from every division of the company, although that is certainly desirable in some businesses, but you should pick managers from the most critical business lines to be part of the initial team of catalysts. There are many ways to form such a team. Eventually you will expect all managers and supervisors to be change leaders, but you can roll out inclusive-leadership initiatives in phases. I advised a national chain that introduced its cultural changes in several stages by geographic region. On the other hand, if you have, say, ten facilities, each with a manager who falls into the category of critical middle management, you might start with bringing two or three of those managers into your team of catalysts and have them inform change throughout the workforce.

We often hear about middle management as the “frozen” layer where new initiatives and strategies go to die. When that happens, it’s largely because the company’s senior leadership has failed to give those middle managers the education and the tools they need to lead change. An important cross-industry study by Behnam Tabrizi of Stanford University revealed that in a randomly selected group of companies, the majority of large-scale change and innovation efforts failed. However, a hallmark of the 32 percent of companies that were successful in making transformative changes was “the involvement of mid-level managers two or more levels below the CEO. In those cases, executives weren’t merely managing incremental change; they were leading it by working levers of power up, across and down in their organizations.”2

Middle managers have a tough job. Lisa Wardell, former CEO of Adtalem, kept an eye on the challenges her middle managers faced when it came to carrying out DEI policies, and she says that without strong guidance and support from above, those managers were perpetually caught between the demands from senior management and the need to ensure daily performance.

“The underlying reason a diversity initiative doesn’t get past middle management is not intent,” she says. “It’s about fear of doing something or saying something wrong. That is why people don’t take risks. It’s why there aren’t talent moves that challenge the status quo. As a middle manager, you might have a team of three people and they all happen to be white males. That’s your team—so you’ll wonder if you’re being asked to switch out someone unless the senior leaders let you know that it’s a journey. Then, once you get someone in there who may not think the same way as you do, you have to have a forgiving environment to make things work.”3

At the same time, it’s imperative that your middle managers have decision-making powers. That’s a function of the times we live in. John Chambers, the former CEO of Cisco, addressed a conference hosted by Great Place to Work in 2017, in which he talked about the accelerating speed of change and the demands that that will place on the workplace of the future. “Companies won’t be able to win if they wait for senior executives to learn about problems and make decisions,” said Chambers. “You’re going to have information coming into your company in ways you never imagined before. Decisions will be made much further down in the organization at a fast pace.”4

It’s up to you as a senior leader to make sure your middle managers can succeed as great leaders for the twenty-first century. That means they’ll need to be invested with the authority to make decisive assignments, hires, promotions, and policy changes within their area, and they’ll need to know they have the ear of senior management when it comes to reporting ideas, problems, and new developments. If they don’t have a full set of tools to operationalize diversity and inclusion, the initiative is doomed, no matter how eagerly the senior teams promote it.

Let’s look at how you build and scale inclusive leadership purposefully and patiently by engaging middle management. My strategy for getting these key catalysts on board can be divided into two main components that are broad but full of complexities, and designed for the long haul:

- Lay out all of your expectations.

- Embark on a multiyear journey of change.

Lay Out All of Your Expectations

Make it crystal clear: you expect every leader to intentionally build a diverse workforce with inclusive work environments. At the heart of everything, you are training this group of catalysts to be the business leaders of the future. Start the conversation by discussing why you’re asking them to change the way they’ve been leading people. It’s because great companies—those that are the most profitable over the long term, those that show the most consistent value over time—know that everyone in the organization counts. Great companies understand that business success depends on developing all of the talent at every level of the organization.

The middle managers you choose as change catalysts may have heard the business case for diversity and inclusion before, but they might not be fully aware of how a DEI strategy can become a part of the overall business strategy. You can talk about why diversity and inclusion will lead to growth through greater innovation, and how you plan to deploy the strategies discussed in chapter 4 to get there.

Present data showing the numbers. The analysis you’ve conducted that shows the racial and gender composition of your company’s workforce can also be broken down by divisions within the organization, so that each middle manager knows how his or her division compares with others in the organization and among industry competitors. Set goals for hiring and promotions; for example, the number of new hires or promotions that should be Black, Latinx, Asian, female, or LGBTQIA+ in each division. Set target dates for these goals, and make it clear that for the middle managers, performance evaluation and compensation (more on that later in this chapter) will be closely tied to attracting and keeping a diverse workforce.

At the same time, let your middle managers know that senior management has their backs and is going to remove barriers and give them the tools they need to meet those goals. Everyone will need time—possibly a year or two—to deconstruct the way they’ve approached hiring, assignments, and promotions. Diversity is always kind of messy up front, because you have to process how an infinite variety of people see the world.

A 2020 study from Catalyst, the global organization that provides thought leadership on creating more inclusive workplaces for women, contains some valuable lessons to impart to your middle management change agents, starting with “get comfortable with the uncomfortable.” Here is more advice from Catalyst:

- Focus on learning, being humble enough to say, “This is more difficult than I want it to be or expected,” and courageously commit to doing things differently.

- Let go of your desire to be right. Consider that the way others may solve a problem or take initiative could be just as effective as your way of doing things, if not more so.

- Focus on helping your employees take ownership of their work. Give them the tools and support to execute on goals and to take great pride in their accomplishments and sense of collaboration.

- Speak up when you see biased behavior. Silence is not support. Allyship is about intentional action that demonstrates support for individuals or groups who are marginalized or underrepresented.5

Present an initiative for promoting those who are underrepresented at the top

What is equally important to keeping your middle management catalysts engaged instead of resistant is positive reinforcement from the top. If, for example, there are initiatives underway to promote underrepresented people to the top, that sends a powerful message to everyone in the organization—and it will help middle managers attract and retain diverse hires. A brilliant example of this is the plus-one approach that Chief Diversity Officer Erby Foster put into action at Clorox.

The idea was that the company could build in change simply by adding diverse leadership incrementally but with an effort to add those diverse leaders across all departments and functions. Within each division, the company should proactively identify knowledge or experience gaps on senior teams and bring in people from diverse backgrounds to fill the gaps. As Foster points out, if you have an ethnically diverse senior team but they all went to the same business school, that isn’t true diversity, because they’ve all learned to approach business problems the same way, so you’ll still have some blind spots that forestall innovative thinking. In that case, it’s important to look further afield, another degree. Hence, plus one.

To identify such gaps, the senior executive teams at Clorox conducted an executive inventory. In less than a year, nearly thirty teams evaluated their makeup and added new people who could bring diversity of thought. Clearly, this kind of intentional diversity creates immediate changes it the composition of a company’s leadership. It’s an excellent way to make sure that you spotlight very capable people of color and make them part of a structure that will remove or dismantle impediments to progress. It also has a strong impact further down the organization.

“If a Black person gets promoted to a senior position, all of the Black employees have a sense that ‘we got promoted,’ ” says Foster. “They see that the company is making some progress, so they want to stay.”

I’ve been in that situation myself. At Nestlé Purina I was promoted thirteen times in fifteen years, and as I moved up the ladder, I founded and led employee resource groups and promoted others who had previously been overlooked. White executives often don’t realize that when you have the first person of color step into a top position, it tells others that they, too, can achieve their dreams. We saw that when Barack Obama became the first Black president, and more recently, when Kamala Harris became the first African American and the first woman to hold the office of vice president. Roxanne Jones, a founding editor of ESPN The Magazine and former vice president at ESPN, wrote eloquently of the impact: “Harris’ journey inspires Black women and girls to break out of the boxes that dictate how we fill up space in the world. It shows us how to pivot and walk freely as multidimensional, unapologetic Black women. We don’t need to be chameleons, changing constantly to fit in.”6

The doors are beginning to fly open. People of color and other minority groups will start finding opportunities elsewhere if their present employer makes them feel marginalized. Employers that lose potential talent this way will be hard-pressed to catch up with more inclusive competitors.

Show your managers how to interrupt bias

I don’t believe that you can eliminate systemic racism and biases just by throwing money at antibias training, but it is very important to help everyone in the organization recognize how biases might affect their actions. When you let your middle managers know that inclusive leadership is going to be mandatory from here on, and biases will not be tolerated, you will most likely have to show them the way to a more inclusive management style.

This is no small feat. Biases are deeply ingrained and often unconscious. You’ll have to change mindsets and change the ways individuals communicate with one another and the judgments they make in the course of a day. Yet it’s a transformation that you instill through concrete steps and programs. The first step is your own intentional efforts to weed out bias. At all times, show your teams what you expect by leading through example.

I’ve talked already about how Lisa Wardell makes a point of calling people out on biased behavior when she feels it’s necessary—thereby letting everyone in the room see inclusive leadership in action. In another example, she tells a story of a meeting with two men and a woman from a company that had a service to sell. All three were white, but in this case the bias was directed at the woman, a young junior executive who was also the one who had done the research and given the presentation.

“I was asking questions, and the woman—I’ll call her Meghan—was answering them,” says Wardell. “The men were letting her speak, yet every time she closed her mouth, one of the men would jump in with ‘What Meghan is saying is …” or ‘just to reiterate …’ as if a woman wasn’t capable of making things clear. I finally told them, ‘If I don’t understand what Meghan is saying, I will let you know. Until then, I’m good.’ ”7

The way Wardell spoke out is one example of being a “bias interrupter.” This is a term that comes from my colleague Joan Williams, a law professor and founding director of the Center for WorkLife Law at the University of California Hastings College of the Law. Williams has documented how subtle forms of racial and gender bias are transmitted through organizational cultures and systems. To call out the deeply rooted expectations that influence our views of people and their abilities, she has created a series of tool kits called bias interrupters, which she defines this way: “Bias interrupters are tweaks to basic business systems (hiring, performance evaluations, assignments, promotions, and compensation) that interrupt implicit bias in the workplace, often without ever talking about bias.”8

Besides injecting bias interrupters into the conversation when needed, a CEO should institutionalize them as part of operational practices and policies. I have used bias interrupters in many ways. Requiring that a diverse slate of candidates be considered for any open role is a form of bias interruption. So is having white managers attend Black and Latinx MBA conferences and using action-learning teams to integrate diverse voices into key projects and expose nondiverse leaders to wider talent in the organization.

But there’s more you can do. Let your middle managers and other key catalysts know that they too will be expected to act as bias interrupters. Addressing structural racism requires having managers who understand the specific ways bias commonly privileges one group, so that they can understand the reasoning behind the new policies, procedures, and incentives. Accomplishing this will require antibias training, but it must be training that does more than just explore the cognitive bases of bias; it must provide concrete strategies for interrupting it.9 Williams’s “Individual Bias Interrupters” workshop does this by explaining how bias plays out on the ground and by giving managers time to brainstorm ways they personally would feel comfortable interrupting it. Facebook is doing something similar in its inclusion training sessions, which give people a chance to brainstorm ways to interrupt bias. Make this kind of training part of the structure: all training, from onboarding to leadership programming, should seamlessly build in continuing education on how bias enters into company culture, at many evidence-based, meet-you-where-you’re-at touch points.

There will be many such opportunities to interrupt biases as you begin the journey to inclusive leadership.

Embark on a Multiyear Journey of Change

We know that it’s going to take several years to reach your goals, so all of your managers and catalysts for change will need to know that you have patience. Present the action plan, asking middle managers to start with easy wins that they can achieve in the first quarter, such as a community-engagement initiative, recruiting interns from historically Black colleges and universities, or launching a supplier-diversity program. Such steps will help build momentum.

Use the momentum to gain more buy-in for a more diverse approach to hiring and assignments. What I’ve always taught my HR group about interviewing job candidates applies to all organization leaders when they’re evaluating candidates for a new job or an important assignment. Have a long conversation with every interested candidate. Don’t set time limits; let the conversation go on as long as it takes to find out who this person really is. Ask candidates questions that will encourage them to talk about what they can bring to the organization beyond their work experience.

Talk with your middle managers, too, about who they have selected for top assignments in the past year and why they’ve selected those people. No doubt perceived potential plays an important role in their selections, but what led them to see that potential? Was it just a matter of someone showing enthusiasm, having impressive educational credentials, or previous experience? Was it a perception of “leadership” qualities or of someone being a “a good fit”?

Middle managers have many balls to juggle when it comes to evaluating their staff, solving problems, and keeping both productivity and team morale high—all of which are important components of a sustainable culture of inclusion. Three of the most useful tools you can provide to help them meet these demands are giving them instrumental roles in action-learning teams, guiding them in their assignment decisions, and training them to spot and interrupt bias.

Make middle managers a part of every action-learning team

I always recommend that middle managers be represented on every action-learning team because they bring an important functional perspective of what can be accomplished. In particular, handpick several middle managers to serve on action-learning teams that are looking at how to achieve greater diversity and inclusion throughout the company, so that those managers will be at the forefront of the transition and see for themselves how previously unheard voices can emerge as leaders when they have the opportunity.

In addition, middle managers are typically the people who decide who is going to get the career-enhancing assignments and future promotions—a task that includes making assignments to action-learning teams. For those who participate in action-learning teams, the work they do becomes a stepping-stone to promotions or to top rankings when it comes to performance reviews, generating new business, sales numbers, and such—which is one of the reasons it’s so important to have a diverse slate of participants. The middle managers you enlist as catalysts for change will have the important task of scoping out potential and choosing who else serves on these teams.

Keep everyone on the alert for biases

As I’ve noted, all of the organization’s leaders are going to be engaged in an ongoing effort to eliminate bias—their own and that of others, conscious and unconscious. By continuously identifying and interrupting biases, you begin to incorporate a new communication style into the organization. The very language that managers use in hiring, performance reviews, assignments, promotions, and compensation will have to evolve to reflect more inclusive practices. The message to be inclusive comes first, but as you start requiring managers at every level to reflect on how they’re judging people and why, they will have to pay closer attention to each individual’s specific contributions and potential. Middle managers, because they interact closely with a large number of employees day to day, have a particularly influential role to play here in being on the alert for biases at every touchpoint.

They will also need to be aware of their own biases, and part of their training must guide them in recognizing how they judge people. For example, bias interruption is critical when it comes to the way your managers review their staff. Make meaningful performance reviews an integral part of the system. To be meaningful, employee evaluations must be specific. I’ve always required my managers to state examples so that it’s clear they aren’t just making assumptions, which can be reflections of blind spots. Otherwise, you risk a culture in which managers and colleagues might reflexively label a Black woman “aggressive” or an Asian employee “reserved” without actually analyzing what that individual has done to earn those adjectives. This is exactly the kind of culture that says “he has a lot of potential” when evaluating a young white male, while young Black employees have to prove what they can do.

Joan Williams says a performance review should begin with criteria directly related to the job requirements, so that you present evidence of a person’s capabilities. For example: “He is able to write an effective summary judgment motion under strict deadlines,” instead of, “He writes well.” Rather than saying simply, “She’s quick on her feet,” you might say, “In March, she gave X presentation in front of Y client on Z project, answered his questions effectively, and was successful in making the sale.” This way, the manager has to keep observing and documenting how effectively her staff members are doing their jobs—so that every evaluation of performance or potential comes with proof.

Keep track of DEI metrics

When a company’s leaders are trying to solve a problem, they gather evidence, set goals, and compile a set of metrics they can use to analyze their progress. As we often say in the business world, if it matters, measure it—so the fact that metrics have long been absent from DEI agendas speaks volumes. In chapter 3 I talked about auditing the culture and setting benchmarks for your progress. As you’re building an inclusive culture, collecting data will continue to be key.

Data analysis will help you identify where the biases are and let you continually gauge how antibias measures are working. Culture is defined by what we measure. Does your company measure the racial, ethnic, gender, and LGBTQIA+ composition in such areas as talent acquisition and development, talent retention, and supplier diversity? You won’t know what you have until you start keeping score.

The data should provide a complete evaluation of how the company finds job candidates, what questions are asked and what is measured in the interview process, how performance is assessed, how promotions are structured, and how the company handles complaints, reprimands, and dismissals. The exact metrics will vary from one organization to another, but the goal is always to measure the frequency of practices that indicate bias.

Take, for example, a measurement of how many people consistently receive top performance ratings and who those people are. Do your performance evaluations show consistently higher ratings for straight white men than for people of color, women, LGBTQIA+ employees, or other groups? Do employees’ ratings fall after they take parental leave or become involved in efforts to increase diversity? I’m thinking, in the lattermost case, of the criticism of Google’s treatment of minority employees, sparked when Timnit Gebru, a Black woman whom the New York Times called “a respected artificial intelligence researcher,” was fired from the company, a firing allegedly tied to her criticism of minority hiring and biases built into Google’s AI systems.10 Data should capture all of the patterns in the way people are evaluated.

Similarly, metrics should be used to give you a snapshot of who is being hired and promoted, whether people are truly receiving equal pay for equal work, who feels they are getting all of the tools they need to excel at their job—and even who feels their contributions to the organization are valued and who is happy with their job. Are the results skewing in ways that show an underappreciation of underrepresented groups? If so, then you know what needs to change.

At Jamba Juice, we polled employees on these questions every quarter. Bonuses for middle managers—in our case, that was general managers for each Jamba Juice café and district managers for the cafés under their jurisdiction—depended in part on the overall health of the culture and on employee engagement as measured in the survey. The other part of their compensation was determined by customer experience, which we measured in a separate survey that customers were asked to fill out online or by phone in return for a discount on their next purchase.

You can also use analysis to evaluate the evaluators. Williams suggests appointing people in the organization to be bias interrupters for multiple purposes—a role that either the chief diversity officer or a group of key catalysts from the HR team might play—and one of their key mandates should be to provide what Williams calls “bounceback.” That is, they make a point of identifying managers and supervisors whose performance assessments consistently show lower ratings for certain groups of people, and then talking through the evidence with them. For example, says Williams in the bias interrupter training materials on her website, “when a supervisor’s ratings of an underrepresented group deviate dramatically from the mean, the evaluations are returned to the supervisor with the message: either you have an undiagnosed performance problem that requires a performance improvement plan or you need to take another look at your evaluations as a group.”

Middle managers should be kept informed on all of this data so that they know how they stack up. They should be able to compare data from their own division with that of others, as well as with that of the company in general. They should be told if their departments consistently show lower performance ratings for certain groups of people. That way they will know when they themselves have work to do, while those who have a great track record for inclusive management can work with other managers who need improvement, perhaps through brainstorming sessions and action learning.

All along the way, of course, they will need senior management to support the recruiting and development of diverse talent, and to make it clear that diversity is mandatory and will be monitored. During his tenure as CDO at Clorox, Erby Foster developed a training intensive that gave the company a ready pipeline of women and minorities with the credentials to begin advancing their careers. From there, he tracked the promotions that occurred and held division managers accountable for promoting a certain number of underrepresented people from within the company each year. Managers received bonuses for meeting minority-representation goals. Even so, when one manager said he just didn’t know of enough qualified minorities and was willing to sacrifice his bonus, it became clear why the CEO must be the one who guides diversity mandates. In a case like that, the CEO has to step in and show the manager that his low diversity numbers are dragging the whole company down. Ultimately the resistant manager at Clorox saw how much of an impact he could make.

“So,” says Foster, “I asked him to become the executive sponsor for the Black employee resource group so that he could help influence their role in the company.” That was another tactic Foster used regularly: at some point, nearly every senior executive acted as a sponsor for an ERG. As a result, the senior executives developed a personal interest in the careers of underrepresented individuals and became advocates for them. Those personal connections, he says, helped eliminate a lot of bias.11

Link managers’ compensation to their DEI metrics

About those bonuses for good diversity numbers. It’s great to be able to tell all of your executive and management teams that they’re receiving a priceless opportunity to grow as powerful leaders for the future, but money speaks even louder.

People don’t like change and, at least subconsciously, know they can stop change just by ignoring it. That is particularly true of middle managers, because of their key role in the trajectory of so many careers. But at every level, you have to give people reasons to embrace the change. Part of that is a no-brainer principle: if you affect their compensation, you have their attention.

The incentive structure for helping create an inclusive culture needs to be tied directly to the goals you’ve established. At Jamba Juice, we instituted a new incentive system in which up to 20 percent of store managers’ compensation was determined by the engagement, climate, and organizational-health scores that came from continually measuring our progress through a variant of the Gallup Q12 survey. I’ve been consulting with a company that measures its year-end manager assessment based on how well the manager has done when it comes to building a future talent pipeline, building a leadership team, and achieving the company’s numerical goals for diversity.

Medallia CEO Leslie Stretch has instituted an incentive system in which 100 percent of his leadership teams’ equity compensation is based on increasing Black representation so that it is on track to reach at least 13 percent by 2023—matching Black representation in the US census. McDonald’s is tying 15 percent of executives’ bonuses to meeting DEI targets, with an aim to have 35 percent of its US senior management come from underrepresented groups by 2025, up from 29 percent when the initiative began in 2021, and increasing the number of women in senior roles worldwide to 45 percent by 2025 and 50 percent by 2030, up from 37 percent in 2021. I should stress that even though the CEO must delegate operational changes, there are no shortcuts. It still begins with having a great leader at the top, and once you’ve made it clear what you expect from both senior and middle managers, it’s more important than ever that as CEO you lead by example. It still falls to the CEO to show that we are all in this together and continually investing in upskilling the workforce so that they will feel relevant and confident.

Empathy must never waver. One of my favorite quotations that I think all leaders should take to heart is from Theodore Roosevelt: “People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.” All that most people in the business world need is a fair chance to be seen for their full selves and talents and passions—and if you give them that kind of chance, they will overdeliver.

Key Takeaway

Middle managers must be key catalysts in creating sustainable change that drives business performance.

Checklist for CEOs

![]() Identify the managers in your organization who are responsible for most of the workforce.

Identify the managers in your organization who are responsible for most of the workforce.

![]() Designate a key group of middle managers as catalysts for change.

Designate a key group of middle managers as catalysts for change.

![]() Train managers at every level in bias interruption.

Train managers at every level in bias interruption.

![]() Adapt overall company goals to middle management’s responsibilities: for instance, hiring and retaining people from underrepresented groups, assigning participation in action-learning teams, learning how to stop bias.

Adapt overall company goals to middle management’s responsibilities: for instance, hiring and retaining people from underrepresented groups, assigning participation in action-learning teams, learning how to stop bias.

![]() Identify knowledge or experience gaps on senior management teams and promote people from underrepresented groups who can provide what is needed.

Identify knowledge or experience gaps on senior management teams and promote people from underrepresented groups who can provide what is needed.

![]() Continue to collect data to identify practices that might reflect bias.

Continue to collect data to identify practices that might reflect bias.

![]() Create a compensation structure that is tied to meeting DEI goals.

Create a compensation structure that is tied to meeting DEI goals.