GLOBAL TRENDS

One of the most notable geopolitical trends of the last five years has been the growing number of states intervening in and shaping conflicts to advance their own foreign policies and strategic agendas. What used to be the preserve of the United States and its Western European allies in the post-Cold War and post-9/11 eras has become a more generalised trend, with powers such as Iran, Israel, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) intervening in multiple conflicts across the world.

These interventions have taken a variety of forms, ranging from the episodic use of airstrikes to the deployment of land and maritime expeditionary forces. Some have been mounted unilaterally, skirting below the radar of international scrutiny, while others have sought wider legitimacy by assembling ‘coalitions of the willing’, such as Saudi Arabia’s intervention in the war in Yemen. Most have supported local allies or partners or proxies. Irrespective of the minutiae of specific interventions, this trend has been on full display in several armed conflicts in 2020 and early 2021.

Armed conflicts amid changing geopolitics

The nature of war has not fundamentally changed in recent years since conflicts are still predominantly internal affairs, in which non-state armed groups play a prominent role. Declared inter-state wars remain rare.1 What has changed is the increasingly multipolar global context in which armed conflicts are being fought.2 Other powerful countries, besides the US, are now trying to resolve or influence the outcome of wars abroad to further their own national goals. Compared to the peak of its unipolarity, characterised by interventions in the Balkans, Africa, the Middle East and Asia, the US has gradually become a distracted hegemon. The shift began under the administration of Barack Obama (2009–17) and continued under his successor, Donald Trump (2017–21), who expressed disdain for US involvement in foreign wars amid a general sense of war weariness in the domestic discourse. There were exceptions, including the US role in the territorial defeat of the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or ISIL) in the Middle East and the US military presence that accompanied efforts to broker an end to the war in Afghanistan ahead of its military withdrawal there.3 Global counter-terrorism missions remained a US priority, albeit with a smaller military footprint than previous interventions. Notwithstanding these, however, US foreign- and defence-policy priorities shifted towards ‘great-power contests’ with China and Russia, alongside the containment of Iran and North Korea. The US duly accorded prominence to conventional, nuclear and cyber deterrence, as well as alliance politics and defence diplomacy in regions of strategic contestation.

Trump was also uninterested in censuring other states’ own military interventions as long as these did not disturb his administration’s core interests, a stance that opened further space for other extrovert powers to fill. Joe Biden’s presidency has stemmed this policy drift in one instance: in February 2021, he announced the end of US support to offensive operations in the war in Yemen, including relevant arms sales – a pointed reference to Saudi Arabia.4 However, censuring a country with which the US has enjoyed close relations over its military intervention is one matter, and the extent to which the US is still able and willing to assert its influence in other armed conflicts remains to be seen.

Military interventions as foreign-policy tool

The Armed Conflict Survey 2021 reports that military interventions by major geopolitical powers have taken place in armed conflicts as diverse as those in Afghanistan, the Central African Republic (CAR), Iraq, Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh, the Sahel, Somalia, Syria, Ukraine and Yemen. What constitutes a ‘major geopolitical power’ is subjective, and the criterion used in this report is to include the wealthiest states (per the G20) that have mounted military interventions in armed conflicts, such as France, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. To feature balanced assessments of the wars in Yemen and Syria, military interventions by Iran and Israel are also covered in this essay.

Source: IISS analysis

Military interventions are understood here to involve sustained military operations in which the state’s armed forces fight independently, augment or fully supplant the combat power of one or more warring factions. These interventions feature expeditionary forces in declared deployments or combat operations conducted from afar with stand-off weapons and can include both declared and undeclared operations. They are distinct from dedicated training or peace-support missions, and from the sale of military equipment, although they may encompass such activities.

Changing Western interventions

Military interventions in 2020 and early 2021 by Western states reflect trends that began after the 9/11 attacks, with Western armed forces deployed alongside local partner states in operations against Islamist armed groups. However, the nature of the threat – and the nature of interventions – has changed. In 2019 the ISIS ‘caliphate’ in the Middle East was defeated and evicted from the territory it held by an international coalition of intervening powers, while the Sahel has grown in importance as a locus of Western military intervention against ISIS-affiliated groups. Moreover, the US will withdraw its armed forces from Afghanistan in 2021.

Exhaustion now characterises US domestic discourse around the utility and wisdom of sustaining large military interventions abroad. As large military counter-terrorism missions decrease, the US engagement in such operations is through its special forces, the training of local security partners and, in some instances, airstrikes by inhabited and uninhabited aerial vehicles (UAVs).5

The UK and France remain the most extrovert of Europe’s military powers. The UK is substantially less engaged in military interventions compared to a decade ago, but the Royal Air Force (RAF) remains in Iraq via Operation Shader (part of Operation Inherent Resolve), which marked its sixth year in 2020 and involves Typhoon aircraft conducting airstrikes against ISIS targets.6 In the Sahel, France’s military leads the multi-state Operation Barkhane, which also entered its sixth year in 2020. French forces are headquartered in N’Djamena, Chad, and mount operations against Islamist armed groups in cooperation with partner states organised under the G5 Sahel group (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger). The US and UK militaries have also contributed to training the armed forces of Sahelian countries.

Russia's and Turkey's many-fronted interventions

Russia and Turkey have recently adopted more assertive stances, intervening in conflicts close or contiguous to their borders, but occasionally stretching further afield (Russia in Syria and the CAR; Turkey in Libya). Rivalry between Russia and Turkey has also shaped their interventions in Nagorno-Karabakh and Syria.

Irrespective of their specific motivations, Russia’s military interventions are all underpinned by an extrovert foreign policy unafraid of challenging or breaching international norms to accrue influence in countries Moscow deems strategically important. Russia has displayed strategic flexibility by pursuing different kinds of intervention depending on its goals and the conflict in question. In Syria, it opted for an overt intervention, deploying a military task force in 2015 that remains in action, as well as using an air base in Latakia and a naval base in Tartus. Conversely, in Ukraine’s Donbas region, the ongoing Russian intervention has been conducted in a superficially deniable way to allow Moscow to undermine Ukrainian sovereignty.7 Russia has used private (Russian) military company Wagner Group in the CAR since 2018, supplementing it in 2020 with the deployment of at least 300 Russian military instructors.8 Wagner Group personnel have also deployed to Libya, although this intervention has not shaped the Libyan (or CAR) conflict as decisively as those in Syria or Ukraine.

Across the Black Sea from Russia, the Turkish military has also become increasingly interventionist across several fronts to accrue influence in ongoing armed conflicts or to pursue the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). In Syria and Iraq, Turkey continued its long history of cross-border military operations against the PKK and its affiliates, with Operation Claw-Eagle in Iraq comprising ground and air operations in 2020 and 2021. By deploying land, air and naval forces to Libya in January 2020 in support of the Government of National Accord (GNA), Turkey stepped up its interventionist ambition, driven by the desire to bolster its future claims on Libya’s natural resources and shore up its influence in the Mediterranean Sea. This intervention has placed Turkey in opposition to General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA), which receives support from Russia and France. In Nagorno-Karabakh, Turkish support, in the form of UAVs and intelligence, enabled Azerbaijan to mount a successful offensive against Armenia in 2020.

As of February 2021, Russia and Turkey do not appear to be experiencing intervention fatigue. Some of their interventions are relatively recent, and neither country has deployed a very large land army abroad that would require maintenance, instead using various combinations of airstrikes, contractors, local allies, task forces and other methods to reduce risk and offset the material costs of deployments. Intervention fatigue may develop in the future, but for now, Russia and Turkey remain enthusiastic armed-conflict interventionists.

The interventions of Iran, Israel and Saudi Arabia

Middle Eastern armed conflicts remain characterised by high levels of external intervention that have exacerbated key regional inter-state rivalries, notably those that pit Iran and its local partners against both Saudi Arabia and Israel. Competition is especially intense between Tehran and Riyadh, with each viewing the other’s influence in the Middle East conflict zones in zero-sum terms.

As part of its campaign for greater regional influence, over several years Iran has expanded its involvement in armed conflict across the region, notably in Iraq, Syria and Yemen. Tehran has sponsored local partners and allies, often augmenting their capabilities with deployments of Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Quds Force personnel. As explained in the IISS Strategic Dossier Iran’s Networks of Influence in the Middle East, Iran employs a mix of ideological, strategic, political and logistical links to a myriad of non-state actors, but ‘Tehran has made no attempt to formalise the status of any of these relationships or the network as a whole’.9 It persisted with this approach in 2020 and early 2021 despite the killing of its main strategist, Quds Force commander General Qasem Soleimani, in a US airstrike in January 2020. Iran’s rivalries with Israel and Saudi Arabia also continued in this period.

Israel’s intervention in Syria is driven by a defensive calculation that Iranian influence so close to its borders must be challenged and eroded, prompting it to maintain the tempo of its offensive air operations against IRGC and Hizbullah targets, with approximately 50 airstrikes in 2020 and more in January and February 2021.10

Saudi Arabia’s intervention in Yemen’s civil war began in 2015 and featured a coalition of Arab countries fighting on behalf of the United Nations-recognised Yemeni government against the Iranian-backed Houthi movement (Ansarullah). A motivating factor to intervene was Riyadh’s concerns that Tehran was consolidating its influence in the country. Over time, Saudi Arabia’s intervention ground to a stalemate. In 2019, the UAE withdrew its military contribution to the coalition; in 2021, the US announced the end of its diplomatic support of and arms sales to Saudi Arabia in connection to the Yemen war. International efforts have instead refocused on empowering efforts to broker a political resolution to the conflict. However, Saudi airstrikes against Houthi targets have continued, while Houthi missiles have been fired at Saudi cities and oil-production facilities. Nonetheless, the Saudi stance in Yemen is increasingly characterised by the fatigue of an inconclusive intervention.

Implications for conflict resolution

As a broadening range of states mount armed-conflict interventions, some of them have gained significant stakes in brokering ceasefires and peace deals in pursuit of their national interests, often circumventing or ignoring both Western states and the UN.

For example, the Russian and Turkish governments have sought prominent roles in the Syrian peace processes. At the height of the Syrian civil war in January 2017, Russia convened the Astana talks with Iran, Turkey and the regime of Bashar al-Assad. Repeat sessions of the Astana talks began to overshadow the parallel UN-run Geneva process. While UN mediation teams dealt with the fractured Syrian opposition and tried to deliver progress on humanitarian issues, the Astana talks were elevated to the level of major-power diplomacy, as Russia, Iran and Turkey hashed out their spheres of influence. In February 2021 in Sochi, Russia convened the 15th meeting of the Astana process as the Syrian conflict entered its tenth year.

In the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, Turkey’s military (backing Azerbaijan’s military offensive) and diplomatic interventions (subsequently playing a key role in the peace negotiations) were designed both to consolidate its role as a military partner to Azerbaijan and to increase its regional influence.11 Russia also benefited from helping to broker the deal, securing a five-year peacekeeping involvement for 1,960 Russian military personnel, which will occupy observation points, including in the Lachin corridor that connects Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh. Major-power diplomacy, conducted at the behest of the warring states’ patrons, has allowed Ankara and Moscow to embed their regional influence and define their spheres of influence in the South Caucasus.

The UN is responsible for mediation efforts to resolve the war in Yemen, but the leverage to end the conflict is distributed between the fighting parties and their external sponsors. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are likely to demand concessions in a future peace deal to reflect their military and financial investment during their five-year intervention. To complicate matters further, the two powers favour different approaches to settling the conflict. The Houthis remain potential spoilers, seeing no need to compromise and receiving continued support from Iran, which is unlikely to end during attempted peace talks.

The presence of powerful intervening states has implications for multilateral bodies involved in conflict resolution. The Syrian case has highlighted the setbacks faced by the UN Security Council (UNSC) as a forum for ending armed conflicts, with Russia repeatedly using its veto to protect Assad’s regime and to continually block resolutions calling for investigations into the latter’s use of chemical weapons. Regional conflict-resolution bodies are also affected, particularly when key member states are involved in the fighting. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) is a pertinent example. While it remains a platform for managing the Nagorno-Karabakh and Ukraine conflicts, member states Russia and Turkey can exert their influence in accordance with their national priorities. In Ukraine, Russia agreed to the remit of the OSCE Special Monitoring Mission (SMM). However, Moscow would never endorse an OSCE mission that runs contrary to its national interests in the country. In Nagorno-Karabakh, although the OSCE has kept talks going for 30 years, Turkey and Russia were able to sideline the process when pursuing their 2020 ceasefire agreement.12

Outlook

In an era of intensifying inter-state competition, the evolution of armed-conflict interventions by powerful states is an important trend to follow. The evidence so far suggests that there is a significant expansion in the number of powerful countries that are willing and able to intervene, albeit with varying outcomes.

Intervention fatigue has set in for Saudi Arabia in Yemen due to the fracturing of its coalition, the loss of US support and the failure to secure a decisive outcome. Other intervening powers seem to have learned valuable lessons from observing the US-led interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan, which involved large deployments on the ground. Russia has so far avoided these circumstances in its own interventions, no doubt also drawing on the wisdom of the Soviet Union’s earlier failed intervention in Afghanistan. Turkey meanwhile appears to have mounted a relatively quick intervention in the Nagorno-Karabakh war, although its Libya intervention may yet prove inconclusive given the complexity of the conflict and the involvement of multiple external players. Its interventions in Iraq and Syria mark the continuation of its long-standing and intractable war against the PKK, to which it appears committed for the long term.

The prevalent trends suggest that the geopolitical conditions could prompt yet more major geopolitical powers to become interventionist. China remains prominently absent from the list; despite its history of border wars, it lacks substantial experience in expeditionary warfare in either the modern or the imperial era, having avoided waging colonial warfare far outside its immediate environs. India is also absent: aside from fighting Pakistan over the disputed Kashmir, its only precedent is its failed intervention in Sri Lanka’s civil war in the 1980s. While China and India both contribute personnel to UN peacekeeping missions, they seem to lack a nascent appetite for mounting interventions in pursuit of national objectives. It is difficult to hypothesise credible circumstances in which this might change. For the sake of conjecture, if Chinese or Indian troops were sent to stabilise a future deterioration in the security of Afghanistan or Myanmar, current evidence would point more to involvement via a UN mission than through unilateral action. A more credible scenario involving the unilateral deployment of Chinese forces would be to protect and secure Chinese nationals and economic investments in Africa, perhaps using China’s military base in Djibouti, or possibly to assist Pakistan against future security threats to Chinese-funded infrastructure projects there.

Germany and Japan continue to face considerable domestic restraints to deploying even in multilateral missions that may face combat. Australia is engaged in a public debate over whether its military would intervene in a hypothetical war involving China, Taiwan and the US, but this discussion is worst-case speculation and scenario planning, not policy. The unofficial club of geopolitically powerful and wealthy states intervening in armed conflicts in pursuit of national goals is likely therefore to remain selective.

A final variable concerns the nature of intervention itself. The rising ubiquity of uninhabited combat vehicles on land, sea and air may change the cost calculus of interventions for militaries that can afford sufficiently sized formations of these technologies and develop practical doctrines to deploy them alongside inhabited platforms and traditional military formations. Another trend is the increasing use of state-backed private military companies to intervene in conflict-riven countries to secure political and economic influence alongside or on behalf of their client.13 Russia’s use of the Wagner Group to test the waters in the CAR and Libya conflicts serve as examples, and Libya’s conflict has also featured mercenaries recruited by Turkey from armed groups it supported in Syria. At the height of their interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan, the US and UK relied extensively on private military contractors to supplement their armed forces. The ways in which contractors are used in future interventions may yet evolve in different directions. The range of powerful countries choosing to engage their services may also widen. More broadly, the changing geopolitics of inter-state competition will continue to influence both the opportunities and the stakes surrounding armed-conflict interventions.

Notes

- 1 Samir Puri, Fighting and Negotiating with Armed Groups: Strategies for Securing Strategic Outcomes, IISS Adelphi 459 (Abingdon: Routledge for the International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2016), pp. 7–8.

- 2 Alexander Cooley and Daniel Nexon, Exit from Hegemony: The Unravelling of the American Global Order (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

- 3 The US has not abandoned stabilisation entirely, and its Global Fragility Act (2019) restated US inter-agency approaches to assist war-to-peace transitions. See US Department of State, ‘Report to Congress Pursuant to Section 504(c) of the Global Fragility Act’, 17 September 2020.

- 4 White House, ‘Remarks by President Biden on America’s Place in the World’, 4 February 2021.

- 5 For instance, in Somalia, US Africa Command (AFRICOM) reported that it had conducted an airstrike against an al-Shabaab compound in January 2021, which followed 52 US airstrikes there in 2020. See AFRICOM, ‘US Africa Command Conducts Strikes on al-Shabaab Compound’, 2 January 2021; and Harm Venhuizen, ‘US Airstrikes in Somalia Continue at Rapid Pace Even After Force Relocation’, Military Times, 26 January 2021.

- 6 RAF, ‘Six Years of Operation Shader’, 29 August 2020.

- 7 See IISS, Russia’s Military Modernisation: An Assessment (London: IISS, 2020), pp. 28–33. Moscow officially denies responsibility for the fighting in the Donbas, despite evidence that Russian soldiers have been heavily involved since the outbreak of the war in 2014. The Russian armed forces have a clear interest in the fighting in east Ukraine, as demonstrated by the Russian military build-up that took place in March and April 2021 in occupied Crimea and alongside Ukraine’s eastern border.

- 8 ‘Russia’s Use of its Private Military Companies’, IISS Strategic Comments, vol. 26, no. 39, 15 December 2020.

- 9 IISS, Iran’s Networks of Influence in the Middle East (London: IISS, 2019), pp. 8–9, 19.

- 10 Israel Defense Forces, ‘2020 in Numbers: A Whole Year in One Article’.

- 11 For context regarding the extent of Turkish military support, see Ece Toksabay, ‘Turkish Arms Sales to Azerbaijan Surged Before Nagorno-Karabakh Fighting’, Reuters, 14 October 2020.

- 12 Pamela Aall, Chester A. Crocker and Fen Osler Hampson, ‘A New Concert? Diplomacy for a Chaotic World’, Survival: Global Politics and Strategy, vol 62., no. 6, December 2020–January 2021, pp. 89–90.

- 13 Sean McFate, Goliath: Why the West Isn’t Winning. And What We Must Do About It (London: Penguin Random House UK, 2020), pp. 132–8.

The protracted nature of internal armed conflicts is well documented: more often than not, civil wars trap countries in cyclical spirals of violence in which conflict relapse is a recurring event.1 Countries are mired in ‘post-conflict’ phases for increasingly long periods; the term itself has become more difficult to define because of its overlap with active conflict and the expanded scope of post-conflict interventions. The last few decades have witnessed increasing interventions focused on post-conflict recovery and peacebuilding, often undertaken in parallel with moments of active conflict. This dynamic is evident in Afghanistan and Colombia (see Box 1), and in other long-standing wars in the Sahel, Somalia and Syria, among others.

The aftermath of war presents pressing security, development and humanitarian issues. A strategic analysis of these areas is essential to understand contemporary armed conflicts and identify appropriate responses and paths to durable peace.

The changing nature of armed conflict

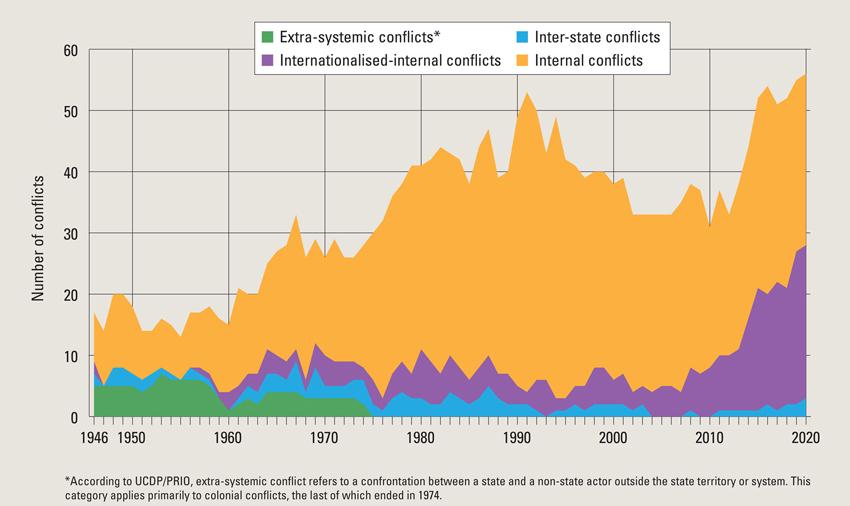

The progressive increase in the number of armed conflicts during the Cold War came to a halt with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. A cooperation momentum within the United Nations Security Council led to an intense period of conflict resolution and a parallel decline in the number of wars over the following two decades. This trend was abruptly reversed with the 2011 Arab Spring and the ensuing spread of conflicts involving the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL (see Figure 1). 2020 witnessed the highest number of conflicts since 1945. The conflict landscape also evolved: intra-state confrontations became even more predominant after 2010, especially those featuring third-party interventions, which have tripled in the last ten years.2 On the other hand, inter-state conflicts have remained very limited since the end of the Cold War.

Sources: UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset version 21.1; UCDP Non-State Conflict Dataset version 21.1; Nils Petter Gleditsch et al., ‘Armed Conflict 1946–2001: A New Dataset’, Journal of Peace Research, vol. 39, no. 5, September 2002, pp. 615–37; Ralph Sundberg, Kristine Eck and Joakim Kreutz, ‘Introducing the UCDP Non-State Conflict Dataset’, Journal of Peace Research, vol. 49, no. 2, March 2012, pp. 351–62; Therése Pettersson et al., ‘Organized Violence 1989–2020, with a Special Emphasis on Syria’, Journal of Peace Research, vol. 58, no. 4, July 2021, pp. 809–25.

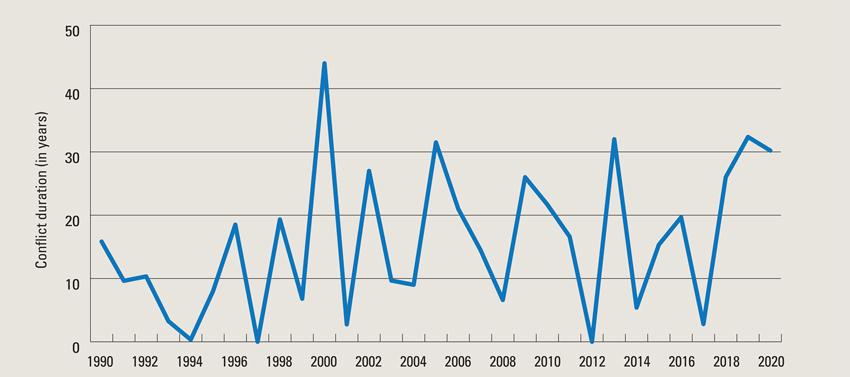

Note: The graph illustrates the average duration (in years) of each armed conflict that ended between 1990 and 2020. The start date of each conflict included in the graph refers to the first year of the conflict in which 25 or more battle-related fatalities occurred, regardless of the total count of deaths before or after that year. The end date of each conflict refers to either the official end year or the year in which the last conflict episode was registered. A unique identification code was used for each conflict in order to collate the data. The information in this graph is current as of the end of 2020 but may be subject to change over time as countries potentially relapse into conflict, thereby replacing the end years which have been considered here.

Sources: IISS calculation based on UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset version 21.1; Nils Petter Gleditsch et al., ‘Armed Conflict 1946–2001: A New Dataset’, Journal of Peace Research, vol. 39, no. 5, September 2002, pp. 615–37; and Therése Pettersson et al., ‘Organized Violence 1989–2020, with a Special Emphasis on Syria’, Journal of Peace Research, vol. 58, no. 4, July 2021, pp. 809–25.

Today’s conflict glut is caused not only by the spike in new conflicts since 2010 and their protractedness (e.g., Libya, the Sahel, Syria, Yemen), but also by the minimal progress made in resolving old ones (Afghanistan, Africa’s Great Lakes Region, Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia and Sudan, among others). The time horizon of armed conflicts has also increased, with conflicts becoming more prolonged starting from the early 1970s and particularly after the Cold War. Conflict duration nearly doubled in the space of three decades: while the average duration of conflicts that ended in 1990 was approximately 16 years, in 2020 it was over 30 years (see Figure 2). In turn, the aftermath of conflict has become more protracted as the active phases of conflicts have themselves extended.

The conflict to post-conflict continuum

The intersection between conflict and post-conflict – and their seeming overlap – is primarily explained by increasing conflict recurrence. Of the conflicts that have broken out since the 1990s, a greater share have been recurrent conflicts instead of new conflicts arising in previously peaceful countries. Between 1989 and 2018, nearly half of all conflicts recurred. More than 90% of recurring conflicts concern the same or similar grievances, highlighting the failure of peacebuilding efforts to address root causes. Conflict recurrence is also explained by the fact that since the end of the Cold War negotiated settlements have become the main modality to end conflict, rather than military victory of one of the warring parties.3 Although the former have been a positive development in terms of reducing human suffering and economic hardship, they seem to have been less effective in preventing conflict relapse.

Nevertheless, conflict recurrence is not a mere repetition of past conflicts. While grievances may be the same or similar, it may be more accurate to say that armed conflicts transition rather than statically recur. If war is the continuation of politics by other means, then conflicts may manifest either violently or non-violently, and war and peace are interacting manifestations of conflict dynamics.

In this vein, the conflict to post-conflict sequence is part of a non-linear transition between war and peace, where the two may either coexist or alternate. The trajectory of armed conflicts is dotted with frequent overlaps between the pre-, during- and post-conflict phases, which are all part of the conflict cycle. While analytically useful, a division of conflict into phases should be accompanied by the concept of war-to-peace transition, if policy responses and interventions are to be well-crafted.4

Overlapping war-making and reconstruction efforts

The non-linear transition between war and peace, including the intersection between war-making and post-conflict measures, is typified by the armed conflicts in Afghanistan and Colombia. Civil wars of a differing nature engulfed the two countries for several decades, and both implemented peacebuilding and stabilisation measures in parallel (see Box 1). While in Afghanistan the reconstruction has been supported and largely financed by the international community to promote state legitimacy, good governance and development in the country, Colombia represented a laboratory for innovative security and development policy (e.g., disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR), and urban violence reduction) and legislation (e.g., post-conflict transitional justice) during active conflict.

Box 1: Post-conflict interventions during war in Afghanistan and Colombia

Over the past several decades, Afghanistan and Colombia have experienced protracted armed conflicts with varying levels of violence, alternating with non-linear transitions from war to peace, as well as conflict relapse. To different degrees, the post-conflict interventions have undoubtedly achieved some positive outcomes in both countries, although persistent war and violence has frustrated durable peacebuilding efforts over the years.

In post-9/11 Afghanistan, the United States-led military intervention that overthrew the Taliban was followed by protracted insurgencies opposing the Western-backed government for the following two decades. The deployment of a UN peacekeeping force – the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan (ISAF), which later became a NATO combat mission – and the US troop surge under the Obama administration did not quell the Taliban insurgency. Neither did negotiation attempts between the Afghan government and the Taliban over the years. An agreement between the Taliban and the US in February 2020 provided for the withdrawal of the latter’s forces from the country during the course of 2021, opening the way for the Taliban to make strides in achieving control of Afghanistan.

The trajectory of the war in Afghanistan in the last two decades was accompanied by a parallel post-conflict reconstruction process resulting in one of the largest official development assistance (ODA) expenditures to date: over US$77 billion between 2001 and 2019.5 The most significant and largest post-conflict development programme in the country, the National Solidarity Programme (NSP), ran between 2003 and 2016 and consisted of over US$1.6bn to establish legitimate governance mechanisms and invest in community-driven development initiatives and infrastructure projects, aimed at generating positive economic and social impacts for rural communities. The Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs), which were civilian–military teams initially set up by the US in 2002 and later taken over by NATO, brought an innovative approach to security governance and reconstruction, promoting local development and good governance with a mix of defence, diplomacy and development. The PRTs’ presence at the local level and their emphasis on flexibility was proven to have a critical, if variable, impact on local dynamics.6 The overall effectiveness of the PRT approach depended on security conditions, on the PRTs’ ability to engage with the local population, and on the contributing states’ approach and level of funding.7 While in United Kingdom-controlled provinces civilian-led missions were oriented to support local governance, the US-led PRTs, mostly located in highly unstable areas, saw a predominant military component involved in both combat and reconstruction operations. In Herat province, under the control of the Italian forces, PRT activities were almost exclusively aimed at reconstruction and socio-economic development.

The conflict in Colombia exemplifies an endemic civil war with a largely domestically driven post-conflict and peacebuilding process. Violence peaked in the early 2000s with the Marxist guerrilla Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) on the brink of taking over numerous regions of the country. By then, the country was mired in historical neglect of rural areas, a dramatic surge in coca cultivation and cocaine production, and territorial disputes between guerrillas and paramilitaries. The Colombian state decided to reverse this trend by pursuing a dual strategy: uproot and defeat the FARC and, together with civil society, invest heavily in post-conflict development and transitional-justice initiatives.

The US-supported Plan Colombia, which consisted of US transfers of over US$9.6bn in 2000–15, applied high military pressure against the guerrillas. While the bulk of Plan Colombia’s budget was allocated to combat narco-trafficking and to counter-insurgency efforts, almost one-third was earmarked to improve socioeconomic conditions and deliver humanitarian assistance.8 Various domestically driven peacebuilding efforts with security and development components were established, aimed at recovering areas under non-state armed groups’ (NSAGs) control and reducing violence in urban and rural settings. For instance, since 1995 and for more than a decade, local-level Peace and Development Programmes have been implemented in several regions to reduce violence and build community institutions. Furthermore, in 2007–16, the policy of Territorial Consolidation included recovery, transition and stabilisation of conflict-affected areas through combined civil–military initiatives in which counter-insurgency goals were complemented by and articulated with socioeconomic development and governance.9

DDR in Colombia traditionally played a critical role in pacifying certain regions and/or achieving separate peace agreements with specific NSAGs. Since the 2000s, emphasis was placed on reintegration to ensure ex-combatants’ progress toward successful reinsertion in society. In 2003–06, over 31,000 paramilitary members from the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) demobilised. In parallel with waging war on the FARC, since the early 2000s the Colombian government also implemented a DDR programme for FARC combatants who decided to desert. By the time a final peace agreement was reached with the group in 2016, the programme had incentivised approximately 19,000 FARC members to abandon the group.

Finally, while still in conflict, Colombia invested in a transitional-justice process to bring justice for victims, hold perpetrators to account and advance reparation and reconciliation. The Justice and Peace Law (2005) was established to guarantee the right to truth, justice and remedy for more than 238,000 war events committed by the AUC – even though few paramilitaries were sentenced.10 In 2011, the landmark Victims’ Law 1448 mandated the legal responsibility of the Colombian state for the recognition, attention and remedy of war victims since 1985. Under this law, over nine million victims have been identified, 88% of which were internally displaced persons (IDPs).11

As in Afghanistan and Colombia, most of the conflicts featured in The Armed Conflict Survey 2021 display some post-conflict interventions aimed at reconstruction, a fact that reinforces the evidence for the tight interactions between the active phase of conflict and its aftermath.

The aftermath of war has also become politicised and contentious, as conflict parties instrumentalise the prospect of aid and support. Reconstruction often entails competing visions of how to implement peacebuilding and how to allocate resources. Incumbent governments may use post-conflict efforts as a tool to reinforce their power and legitimacy – something that typically can fuel further violence. In addition, in many cases in sub-Saharan Africa, the nature of the state is far removed from the Westphalian model promoted by Western-sponsored reconstruction efforts: therefore, it is more a case of ‘state-building’.

The trajectory of post-conflict intervention

The current use of the label ‘post-conflict’ and its practical application derive from a particular period in history after the end of the Cold War. The end of the systemic confrontation between the US and the Soviet Union unlocked the resolution of a series of armed conflicts around the globe. Angola, Cambodia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Mozambique and Namibia are examples of internal armed conflicts that were inextricably tied to the bipolar international order and that, to different degrees, achieved permanent resolution after 1991.12 This new era of UN Security Council activism also led to novel, but then standardised, approaches to rebuilding countries after war.13

The post-Cold War emergence of peacebuilding (led by multilateral institutions) resulted in an overarching policy focus on addressing the physical and human consequences of conflict. This focus targeted the immediate phase after violence halted, which policymakers labelled ‘post-conflict’. The term ‘reconstruction’ was added to signal the set of actions to be prioritised during this phase. ‘Post-conflict reconstruction’14 was then adopted as an overall formula for economic, social, institutional and security activities to be implemented with the support of international actors.15 While politics was purposefully left out of this equation – out of respect for sovereignty concerns – the post-conflict reconstruction approach implied that technocratic solutions and the successful execution of programmes in key areas would translate into successful and durable outcomes. The presumption that reconstruction could move forward successfully without considering the dynamics of the concluded war (and the political implications of the aftermath of war) has proven overly optimistic.

A fundamental disconnection took hold between international (i.e., Western) peacebuilding proponents and national elites in recipient conflict-affected countries, especially in Africa. While the former perceive reconstruction efforts as a new social contract, local elites see reconstruction as a discrete phase of war politics. Conflict-affected countries lack the capacity to implement peacebuilding policies and tend to perceive them as disconnected from the country’s social and political systems. Furthermore, local elites in countries with endemic state fragility (i.e., where the post-colonial state is perceived as alien and sovereignty is anchored in pre-existing and pre-colonial institutions) may see peacebuilding as just another opportunity for resource extraction and maximisation of political power.16 Notably, this has been the case for sub-Saharan African elites in conflict-affected countries, who would maintain an interest in preserving some level of state fragility or armed conflict.17

The 9/11 attacks on the US marked an inflection point. The ubiquity of transnational terrorism led to the adoption by state actors of a security paradigm anchored on counter-terrorism strategies, to which international institutions also adapted. For over a decade, the fight against al-Qaeda was the prism through which the US and its allies viewed many internal conflicts. With its emphasis on security, the war on terror overran reconstruction and development goals, grossly simplifying them with dangerous consequences. The post-conflict debacle in Iraq that followed the 2003 US-UK invasion was the tipping point of a post-conflict ‘fantasy’18 in which many post-conflict countries pursued the sudden but unrealistic establishment of pro-market-liberalisation institutions and multi-party democracy.

At the same time, multilateral actors (such as the UN and the World Bank) dedicated increasing attention to the sources of state fragility and the scope of post-conflict interventions. The progressive expansion of UN peacekeeping operations to include more robust security mandates and capacity-building functions, among others, is the clearest evidence of this trend. Other actors (including donors, development banks and civil society) spearheaded approaches to address war through integrated diplomatic, security and development efforts. While many of these initiatives are nascent, interventions to address conflict and post-conflict have become more intertwined than ever. Standard approaches that may have been considered ‘best practice’ were shown to be inadequate in particular cases, while the blurring of the line between conflict and postconflict also challenged the putative impartiality of international actors in implementing peacebuilding programmes. As a result, expectations are now at a historic low regarding what can be achieved by external actors to address the ravages of war where it has become endemic.

Whither post-conflict?

The last decade witnessed an upward trend in the number and lethality of internal armed conflicts, reaching a record high in 2020. Therefore, there is urgent need to reappraise the different types of interventions that take place in the aftermath of conflict, as well as the timing of these interventions. The current international system is characterised by US-China global competition and there are tensions in several regional theatres: the recent trend of third-party intervention in internal armed conflicts by state actors includes Russia, the US, Turkey, Israel, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, among others. While internal conflicts become more complex, the post-war phase too is characterised by a proliferation of state actors with their own interests.

The overlapping international and domestic dimensions of civil wars – exemplified by Colombia and Afghanistan – invite further reflection on the scope of post-conflict interventions and highlight the need for a conceptual and operational clarification of the ‘post-conflict’ label. The expansion in scope and mandates of peacekeeping operations has also seen them endure for far longer periods,19 itself an indicator that the approach to peacekeeping needs to be adapted if it is to offer a proper solution to conflict.

Four factors in particular need to be considered more carefully. Firstly, timing: a prolonged and unstable conflict aftermath can be disaggregated into a short-term or immediate post-conflict phase (for example, following a peace settlement or a military victory), and a more long-term and protracted postconflict. The policy and operational implications are different for each moment, and the short- versus long-term distinction should be a guiding principle when interventions are conceived. Secondly, a taxonomy of post-conflict typologies may be based on if and how the conflict ended and what is needed next. Conflict and post-conflict phases are often simultaneous, while some conflicts have seen postconflict interventions take place only once violence definitively ceased. Thirdly, the way a conflict ends (i.e., either by military victory or by peace agreement) has profound implications for the politics of the post-conflict phase. Finally, the type of investments needed during post-conflict is a key variable for which different strategies must be implemented. For example, the geographic scope of post-conflict may be limited to specific regions or areas, or peacebuilding may need to be implemented at the national level.

Post-conflict is commonly considered a discrete phase – separate from war – in which reconstruction occurs in the absence of violence. Yet contemporary conflicts feature frequent overlap between active conflicts and post-conflict. In turn, the quest for sound policy solutions to stabilise countries and regions and promote development depends on a reassessment of the boundaries and tenets of what post-conflict is and implies. The long aftermath of war requires its own special study that does not borrow too heavily from the classic understanding of peacekeeping and reconstruction policies but instead appreciates that ‘peace’, like ‘war’, has its grey areas.

Notes

- 1 See, for example, United Nations and World Bank, Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict (Washington DC: World Bank, 2018); Lise Morjé Howard and Alexandra Stark, ‘Why Civil Wars Are Lasting Longer’, Foreign Affairs, 27 February 2018; and Julie Jarland et al., ‘How Should We Understand Patterns of Recurring Conflict?’, Conflict Trends, Peace Research Institute Oslo, 27 May 2020.

- 2 See ‘Interventions in Armed Conflicts: Waning Western Dominance’, in IISS, The Armed Conflict Survey 2021 (Abingdon: Routledge for the International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2021), pp. 16–21.

- 3 Adam Day and David Passarelli, ‘Governing Uncertainty’, UN University Centre for Policy Research, March 2021, p. 37. See also Sebastian Von Einsiedel, ‘Civil War Trends and the Changing Nature of Armed Conflict’, Occasional Paper 10, United Nations University Centre for Policy Research, March 2017; Jarland et al., ‘How Should We Understand Patterns of Recurring Conflict?’; Paul D. Williams, ‘Continuity and Change in War and Conflict in Africa’, Prism, vol. 6, no. 4, 16 May 2017, pp. 33–45; and Barbara F. Walter, ‘Why Bad Governance Leads to Repeat Civil War’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, vol. 59, no. 7, 31 March 2014, pp. 1242–72.

- 4 See Philippe Bourgois, ‘The Continuum of Violence in War and Peace: Post-Cold War Lessons from El Salvador’, in Nancy Scheper-Hughes and Philippe Bourgois (eds), Violence in War and Peace: An Anthology (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004); Mark Duffield, Global Governance and the New Wars: The Merging of Development and Security (London: Zed Books, 2014); Robert Muggah (ed.), Security and Post-Conflict Reconstruction: Dealing with Fighters in the Aftermath of War (New York: Routledge, 2009); and Michael Pugh (ed.), Regeneration of War-torn Societies (London: Macmillan Press, 2000).

- 5 World Bank, ‘Net Official Development Assistance and Official Aid Received (Current US$) – Colombia, Afghanistan’.

- 6 See US Department of State, US Agency for International Development and US Department of Defense, ‘Provincial Reconstruction Teams in Afghanistan: An Interagency Assessment’, PN-ADG-252, June 2006.

- 7 William Maley, ‘Provincial Reconstruction Teams in Afghanistan – How They Arrived and Where They Are Going’, NATO Review, Autumn 2007.

- 8 Colombia, National Planning Department, SINERGIA, ‘15 Años del Plan Colombia’ [15 Years of Plan Colombia], 4 January 2016.

- 9 Juan Carlos Palou et al., ‘Balance de la Política Nacional de Consolidación Territorial’ [Stocktaking of National Policy of Territorial Consolidation], Ideas for Peace Foundation (FIP), Report Series no. 14, September 2011.

- 10 Juan David López Morales, ‘Las deudas y aciertos de Justicia y Paz, a 15 años de su creación’ [Failure and Success of the Justice and Peace Law, 15 Years After Its Adoption], Tiempo, 28 July 2020.

- 11 Government of Colombia, Unidad Para Las Victimas, ‘Registro Único de Víctimas’ [Registry of Victims]; See also Colombia, Ministry of Justice and Ministry of The Interior, ‘Ley de Víctimas Y Restitución de Tierras’, [Victims’ Law and Land Restitution], 2011.

- 12 The end of the Cold War did not result in these internal conflicts concluding at once or in a similar manner. While some were permanently settled (e.g., Cambodia, Mozambique, Namibia, Nicaragua), some relapsed almost immediately (e.g., Afghanistan, Angola) and others morphed, taking on different dynamics (e.g., El Salvador, Guatemala, the Great Lakes Region, Somalia) and/or entering new phases (e.g., Colombia, Indonesia, Peru, Sudan). Finally, a series of conflicts unraveled in former Soviet territories or spheres of influence (e.g., the Balkans, Chechnya, Nagorno-Karabakh, Tajikistan).

- 13 The RAND Corporation was among the first proponents of standard approaches to post-conflict reconstruction. See James Dobbins et al, America’s Role in Nation-Building: from Germany to Iraq (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2003).

- 14 The term ‘reconstruction’ as associated with the aftermath of war traces back to the American Civil War. Subsequently, it was embedded in the post-1945 international order through the establishment of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank). However, it is only after the Cold War that ‘reconstruction’ became a ‘hegemonic strategy’. See Colin Flint and Scott Kirsch, ‘Introduction: Reconstruction and the Worlds that War Makes’, in Colin Flint and Scott Kirsch (eds), Reconstructing Conflict: Integrating War and Post-War Geographies (Burlngton, VT: Ashgate, 2011).

- 15 Barnett et al compile a list of the all the terms coined and adopted by different donors and multilateral organisations to define their engagement to sustain peace. See Michael Barnett et al, ‘Peacebuilding: What Is in a Name?’ Global Governance, vol. 13, no. 1, January-March 2007, pp. 38–41.

- 16 It is indicative that Cambodia and Mozambique – both reputedly good examples of practices of transition to peace – have high levels of corruption and impunity, a trend that shows the power of elites in capturing state resources. See Christopher Cramer, Civil War Is Not a Stupid Thing: Accounting for Violence in Developing Countries (London: Hurst & Company, 2006).

- 17 See Jean-Francois Bayart, ‘Africa in the World: A History of Extraversion’, African Affairs, vol. 99, no. 395, April 2000, pp. 217–67; and Pierre Englebert and Denis M. Tull, ‘Postconflict Reconstruction in Africa: Flawed Ideas About Failed States’, International Security, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 106–39.

- 18 Cramer, Civil War Is Not a Stupid Thing: Accounting for Violence in Developing Countries, pp. 245–78

- 19 Von Einsiedel, ‘Civil War Trends and the Changing Nature of Armed Conflict’, p. 4.

Before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the world was facing unprecedented numbers of people on the move through voluntary economic migration (orderly and irregular) and forced displacement (refugees, asylum seekers and internally displaced persons (IDPs)). While globalisation, interconnectedness, livelihood inequalities and economic-activity trends have driven economic migration numbers upward, conflicts, violence and recurrent environmental crises have forced greater numbers to flee their homes over the last two decades. Most South–North migrants are in high-income countries, while an even higher proportion of forcibly displaced people are in the Global South. As economic migration has diminished considerably due to coronavirus-related restrictions, forced displacement has continued to increase. The impact of COVID-19 will likely exacerbate current drivers of migration and conflict, and effective global governance will be required to address interlinkages between these drivers and the root causes of people movement in the Global South.

The nexus of armed conflict and people movement

Economic migrants seek to improve their livelihoods by making a voluntary choice to move to another location to match their opportunities with their skills. Forcibly displaced people seek personal safety and leave their places of residence due to conflict, violence or persecution, moving either within their own country to seek safety or crossing borders to seek asylum. Some forced and economic movement may be attributable to climate-related resource depletion, which in turn can trigger armed conflict. For instance, a major drought in Syria in 2009–10 led to massive crop failure and loss of livelihoods that, together with anti-government sentiment and a lack of government response, was among the factors leading to armed conflict and large-scale forced displacement.

As forced displacement and economic migration are governed by different frameworks, distinguishing between them is essential but complicated. Overlap, confusion and complications emerge when irregular economic migrants1 and refugees move along the same routes (notably within and from Africa towards Europe, and from Central America towards the United States), and when these movements are mixed with climate-induced voluntary or forced movements. Another problem is the difficulties receiving countries face in understanding the difference between economically driven migration and conflict-induced forced displacement, and the fundamental differences between the terms refugee and migrant. This confusion has influenced the articulation of public discourse and ideas regarding how to reconcile the conventional rights of people on the move with national policies and priorities. Often this discourse has contributed to destination countries’ defensive and restrictive policy responses, which have involved externalising core aspects of migration management and asylum processing as part of a closed-border approach, combined with support to developing countries receiving displaced people.

Forced displacement and armed conflict are intrinsically linked. All armed conflicts generate some level of forced displacement while all refugee movements and some protracted internaldisplacement situations can be traced back to armed conflict. Therefore, solving some of the most intractable conflicts would go a long way towards ending some of the worst displacement crises. A few major conflicts (in Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan/South Sudan, Syria and Yemen) have produced the majority of the world’s forcibly displaced population, most of whom are hosted internally or in neighbouring countries.2

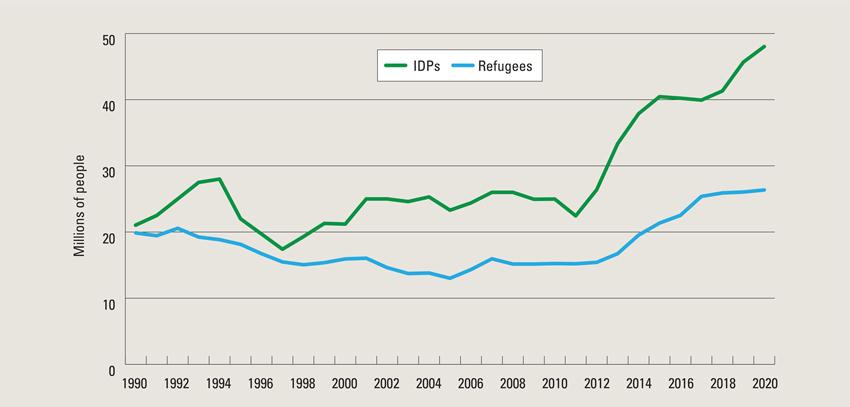

Dynamics and governance structures pre-COVID-19

The total number of people on the move by the end of 2019 was estimated at 327 million, of which 82m were forcibly displaced (34m refugees and asylum seekers and 48m IDPs (see Figure 1)).3 The remaining 245m were economic migrants of whom approximately 180m were of working age, with the remaining balance being children and elderly family members.4 Forcibly displaced populations have a smaller working-age proportion. In addition, irregular movements of economic migrants are estimated at several million, but exact numbers are difficult to document.

Sources: IDMC; UNHCR; UNRWA

While most economic-migrant workers (111.2m or 67.9%) are employed in high-income countries, recent years have seen an increasing proportion of economic migrants working in middle-income countries as compared to high-income host countries. An Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)-International Labour Organization (ILO) study has suggested that this change could be attributed to economic development in middle- and low-income countries, particularly those bordering countries that produce migrant workers, together with migration policies in high-income countries.5

The dynamics of orderly and irregular migration largely follow economic developments in both the origin and host countries, and until the coronavirus pandemic both forms of migration were on the rise amid widening inequality and record-high youth-unemployment levels in most origin countries. However, rising xenophobia and isolationist nationalistic policies in host countries, which show increasing disregard for human rights, have made irregular economic migration more difficult. This is in stark contrast to a concomitant trend to facilitate migration at regional levels (for example via the abolition of visa requirements6 and expansion of free movement of persons through mechanisms such as the African Union’s 2018 free-movement protocol and the new Intergovernmental Authority on Development Free Movement Protocol). Some African governments point to the fact that they have opened their borders and expanded rights while the West has done the opposite. On a more positive note, the European Union and individual member countries have begun providing development resources in support of these genuinely inclusive refugee policies in some African countries as a first step to contain and mitigate the impact of people movement within Africa.

Most European countries continue to close their borders to refugees and economic migrants, even when foreign labour could have a positive impact on domestic economies. Similar trends have been seen in the US. In the face of these dynamics, there has been growing international recognition of the need for better management of economic migration, leading to the 2018 Global Compact for Migration (GCM).

Since 1951, forced displacement has been governed by international instruments. In the years following the adoption of the Refugee Convention, many conflicts were resolved and displaced people found solutions to their plight. However, in the last three decades new armed conflicts have emerged that have not been resolved, including the long-running conflicts in Afghanistan, the Caucasus region, eastern Congo, Myanmar, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. This has led to the numbers of forcibly displaced persons increasing. As there are no eminent solutions, they face long-term livelihood challenges and are often hampered by exclusive and restrictive policy environments in asylum countries, leading to costly humanitarian dependency as opposed to enhanced self-sufficiency. A combination of nationalistic policies, dwindling official development assistance (ODA) resources and institutional and organisational resistance to change has meant that mitigation efforts have been insufficient, highlighting that the system is unsustainable and lacks global institutional mechanisms linking forced-displacement issues with conflict resolution.7 Some of these challenges began to be addressed from 2015, notably spurred by the magnitude of the Syrian crisis. Substantial development efforts by the World Bank and the EU were combined with a growing understanding of the need to broaden the governance mechanism towards a new approach, culminating in the 2018 Global Compact on Refugees (GCR).

The Global Compact on Migration (GCM) and the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR)

The GCM provides the first global framework for migration with the main objective to support international cooperation to address migration challenges. Its non-binding nature, and the fact that not all countries have signed up, has been a challenge to its implementation. The GCR in turn has a comprehensive and development-oriented vision, introducing a focus on preparedness, prevention and localisation. It is seen by many of the signature countries as an important step towards real change. Despite its non-binding nature, implementation is advancing, with real breakthroughs hampered by a lack of progress in achieving the central goal of agreement on burden and responsibility sharing.

COVID-19's impact on human mobility and armed conflict: Rethinking global governance and solutions

For people on the move, the coronavirus pandemic has created disproportionate health, economic and safety challenges by exacerbating pre-existing problems and stifling economic opportunities. The pandemic has also had a direct impact on national and international ability to provide health services, with particular impact on low-income countries that are affected by conflict and with weak capacity. The pandemic has also caused an unprecedented global economic recession, leaving 115m people in extreme poverty – the worst setback in a generation8 – and hampering livelihood opportunities across the globe, particularly in low- and middle-income countries and for the most vulnerable economic migrants and forcibly displaced people. In this way, COVID-19 further widened pre-existing inequality gaps. This is likely to expand mobility pressure and drive people to migrate at a greater risk, despite restrictions on movement and, at least in the short term, declining demand for migrant work. The pandemic has provided governments with a convenient reason to close borders to refugees and migrants, which has also restricted opportunities for people to seek asylum.

Regarding the pandemic’s long-term impact on economic migration, economic considerations may carry the day: irregular migration may pick up again as travel restrictions are gradually lifted. The socio-economic consequences of the pandemic have been severe in many developing countries, so it can be assumed that increasing numbers of people will seek to move. As vaccination coverage progresses (albeit with slower progress in the Global South) and the pressure from conflicts and unresolved inequality between the Global North and South persists, both forced and economic movements will increase again, likely with even higher risks. It is evident that COVID-19’s impact on conflict, violence and war will continue to be significant; so too will be the impact of conflict on forced displacement and economic migration.

The coronavirus pandemic has impacted global efforts to govern people movements, leading to reduced demand for legal migrants amid declining economic activity. As mentioned above, the demand is likely to increase in the future with calls to stimulate economic recovery. This context will emphasise the need for operationalising the GCM. The pandemic has had a negative impact on GCR implementation, with reduced political focus on its implementation and fewer ODA resources available for burden and responsibility sharing. The pandemic has shown that drastic measures to close borders, societies and economies can be taken, albeit on a temporary basis. It should then also be possible to make drastic changes in approaches to mobility, in order to effectively operationalise the full visions of the GCR and GCM, even if this calls for permanent and controversial change. An important feature of such change would be a much stronger emphasis on localisation.

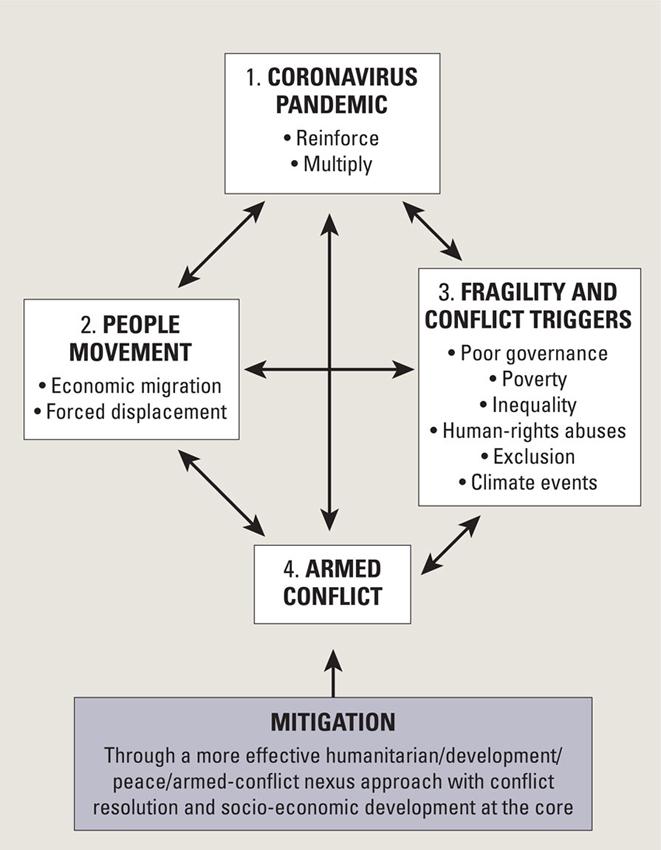

The vicious cycle of people movement, socioeconomic trends, armed conflict and the coronavirus pandemic

To understand fully how the pandemic has impacted upon people movement, socio-economic trends and armed conflict, it is important to look at how these issues influence each other. Figure 2 provides an illustration of this. It highlights how the pandemic reinforces and multiplies these elements and which mitigation measures are required. The listed fragility and conflict triggers represent socio-economic and developmental trends, and are therefore impacted upon by international-aid architecture. The figure emphasises the importance of the interconnectedness of each of the individual parts and the need for forward-looking trend analysis.

The most important COVID-19-induced dynamic related to the movement of people is that while economic migration has reduced, forced displacement continues to increase as old conflicts linger and new ones emerge. This stimulates the vicious cycle by which an economic slump in the Global South generates more conflict; conflicts produce more forced displacement; and the economic slump increases the propensity for economic migration, which is stifled by border-crossing restrictions. All these factors add pressure on people movement.

Poor governance, inequality, poverty, exclusion, human-rights abuses and the slow and sudden onset of climate-related disasters are threat multipliers, key conflict drivers and root causes of forced displacement and sometimes economic migration.9 People movement can be both a result of conflict drivers and a trigger for more conflict. The coronavirus pandemic exacerbates conflicts by increasing social and economic vulnerability, which in turn impacts upon these conflict drivers, leading to increases in forced displacement. The pandemic-induced economic slump further incites people to migrate for economic reasons. Therefore COVID-19 also has an indirect impact on community tension and migration. The pandemic has led to a reduction in economic-migrant remittances, thereby increasing poverty in middle- and low-income countries and indirectly impacting conflict propensity. These developments risk leading to further exclusion, with forcibly displaced people facing deeper poverty (adding to grievances and tension) and conflict propensity.10

A localisation approach to aid is proposed as part of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the New Way of Working,11 and indeed the GCR and GCM. There is growing international consensus – reflected in reforms to UN peace architecture – that ODA should be implemented through and by local structures.12 A localisation approach would improve aid efficiency by supporting national ownership and local capacities and improving sustainability and protection of human rights while reducing the pressure on forced and irregular economic movements. This approach would cost less than mitigation efforts implemented in developing countries by external agencies. It could also reduce conflict drivers in some affected regions. The national and international response to COVID-19 has made it clear that localisation is crucial to achieving results. However, it has also further highlighted that international-aid architecture is incredibly resistant to such change. Localisation is indirectly linked to conflict dynamics and peacebuilding. The UN peace architecture continues to focus on armed-conflict resolution while the impact of the pandemic has inspired further emphasis on preventive efforts. These new efforts focus on national ownership and leadership, a theme that links to the SDGs given the role of inequality and exclusion as drivers of conflicts; political buy-in from member states and links to the World Bank’s new ‘fragility, conflict and violence’ approach; and conflict sensitivity in response to COVID-19’s seismic secondary impacts.13

The historic shock of the Second World War led to the UN Charter and other frameworks to secure global peace. The COVID-19 shock could similarly be inspiration for a new charter with a smarter multilateral approach to securing greater equality and climate solutions, preventing armed conflicts and addressing challenges faced by people on the move.

Conclusion

The main concerns for the future are how and to what extent the coronavirus pandemic will continue to exacerbate armed conflict and related forced displacement, as well as influence South-North and South-South irregular economic migration. This analysis has highlighted two interrelated narratives that are central to the future trends of people movement and armed conflict. One concerns economic development and people-movement policies in the Global North. The other concerns the need to build a new impetus for poverty alleviation and conflict prevention and resolution in the Global South.

Regarding the pandemic’s long-term impact on people movement and armed conflict, it is reasonable to conclude that COVID-19 is here to stay in one form or another, and its impact level will stabilise over the coming years. The global economy will also have to adjust to the new normal. Wealthy countries will potentially need a larger migrant workforce to regenerate their economies. While this was the case before the pandemic, it will be even more important as part of the coming economic rebound. However, this need is at odds with nationalistic-driven restrictions in the Global North. In the long term it is likely that economic considerations will take priority. The likely result is differentiated and selective economic migration along geographic and cultural-historical proximity lines, which would increase fragility, frustration and economic-migration pressure in the Global South. Countries in the Global South will need external support to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on poverty and inequality, which in turn would contribute to the prevention of new armed conflicts and to solutions for ongoing struggles.

COVID-19 is an entirely new entity as well as a multiplier of existing weaknesses and drivers, presenting new opportunities and challenges. It exposes existing economic inequalities and system deficiencies to an extent that has not been seen before, and highlights the need for fundamental corrective action, including through localisation approaches.

The centre of gravity for mitigation efforts may need to be pursued in the Global South, which is home to most armed conflicts and most of the world’s forcibly displaced people, as well as a growing destination for migrant workers. Minimising conflict-induced forced displacement and reducing the propensity for irregular economic migration will require building political will for an agreement on burden- and responsibility-sharing that addresses both forced-displacement and economic-migration challenges and opportunities. It will require a redoubling of efforts to combat inequality between the Global South and Global North. A state-led, global-systems change that improves approaches to humanitarian development, peace and armed conflict – including conflict prevention and resolution and the full implementation of global frameworks for refugees and migration – would have a positive impact on such efforts. This change is of geopolitical importance: if support to the Global South is not provided, the lasting effects of COVID-19 will lead to further conflict and war, generating additional forced displacement and irregular economic migration that will increase instability at the global, regional and national levels.

Notes

- 1 For this essay, defined as movement that ‘takes place outside the laws, regulations, or international agreements governing the entry into or exit from the State of origin, transit or destination’. See International Organization for Migration, ‘Key Migration Terms’, 2011. It is important to note that the phenomenon of irregular migration refers to both the movement of people in an undocumented fashion, and irregular migration flows.

- 2 World Bank, Forcibly Displaced: Toward a Development Approach Supporting Refugees, the Internally Displaced and Their Hosts (Washington DC: World Bank, 2017), p. 88.

- 3 IDPs estimates vary across sources. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), there were more than 50.9m IDPs in 2019, considering conflict and environment displacements. See IDMC, ‘2020 Internal Displacement’, Global Internal Displacement Database.

- 4 See Migration Data Portal, ‘Types of Migration: Irregular Migration’, 2020; Tijan L. Bah et al., ‘How Has COVID-19 Affected the Intention to Migrate via the Backway to Europe’, Policy Research Working Paper WPS9658, World Bank Group, 12 May 2021; and UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), ‘Global Trends in Forced Displacement – 2020’, UNHCR Flagship Reports, 18 June 2021.

- 5 OECD and ILO, How Immigrants Contribute to Developing Countries’ Economies (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018).

- 6 European Migration Network, ‘Impact of Visa Liberalisation on Countries of Destination: Synthesis Report for the EMN Study’, March 2019.

- 7 Niels V. S. Harild, ‘Keeping the Promise: The Role of Bilateral Development Partners in Responding to Forced Displacement’, Evaluation, Learning and Quality Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Denmark, May 2020; and UNHCR, ‘Outcomes of the Global Refugee Forum 2019’, Global Refugee Forum 2019.

- 8 Tara Vishwanat, Arthur Alik-Lagrange and Leila Aghabarari, ‘Highly Vulnerable Yet Largely Invisible: Forcibly Displaced in the COVID-19-induced Recession’, Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement, 20 November 2020; and European Migration Network, ‘Impact of Visa Liberalisation on Countries of Destination: Synthesis Report for the EMN Study’, European Commission, March 2019.

- 9 Hartwig Schafer, ‘The Drivers of Conflict: Where Climate, Gender and Infrastructure Intersect’, World Bank Blogs, 5 March 2018.

- 10 Dilip Ratha et al., ‘Migration and Development Brief 34: Resilience: COVID-19 Crisis through a Migration Lens’, (Washington DC: KONMAD-World Bank), 2021); and Maha Kattaa, Tewodros Aragie Kebede and Swein Erik Stave, ‘Impact of COVID-19 on Syrian Refugees and Host Communities in Jordan and Lebanon’, International Labour Organization, 2020.

- 11 UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘The New Way of Working’, 10 April 2017.

- 12 See, for example, Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments, UN Development Programme and UN-Habitat, ‘Roadmap for Localizing the SDGs: Implementation and Monitoring at the Subnational Level’, June 2016; UNHCR, ‘The Sustainable Development Goals and the Global Compact on Refugees’; and International Organization for Migration, ‘Global Compact for Migration’.

- 13 Paige Arthur, Céline Monnier and Leah Zamore, ‘The New Secretary-General Report on Peacebuilding and Sustaining Peace: Prevention Back on the Agenda’, Centre on International Cooperation, New York University, 10 September 2020.