Overview

The Americas’ conflict landscape is characterised by grey zones between organised crime and political violence. Multiple criminal groups fight each other and the government, largely driven by competition over lucrative illicit economies, while increasingly challenging the state’s territorial control and monopoly on the use of force. They try, and often succeed, to infiltrate state institutions and influence politics, using intimidation and violence but also electoral votes they control as bargaining chips. In some cases, they also play a quasi-state role, providing goods and services and ensuring basic governance in their areas of control. This was in full display during the coronavirus pandemic, with gangs across the region enforcing (or imposing) lockdown measures, distributing essential goods and personal protective equipment, and fixing prices of critical goods. In sum, although the main motivations of conflict are not ideological (with the exception of Colombia and to a lesser extent Brazil), violence is often used for political purposes and to fundamentally undermine public security and ultimately the state’s authority.1

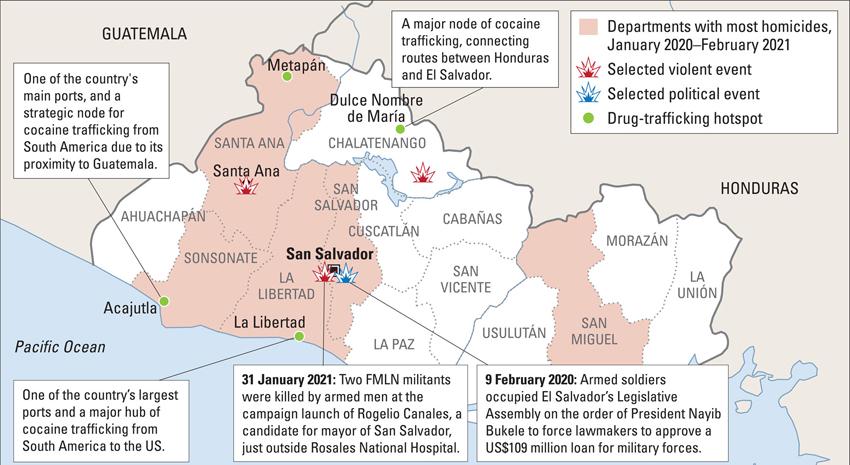

Conflict is particularly ripe along the transnational drugs routes that stretches from Colombia, South America’s coca cultivation and production powerhouse, to the main markets in the United States (through Central America and Mexico), Brazil and (through the latter) Europe. This means that policies in destination markets (especially in the US) directly influence the evolution of conflict. In particular, hardline drug policies promoted by the US and espoused by most Latin American countries have failed to curb illicit-drugs economies, thereby perpetuating violence.2 The nexus between violence, migration and regional instability also raises the global importance of Latin American conflicts despite their inherently internal nature, without any formal intervention by external powers.

Sources: IISS; Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), www.acleddata.com; El Salvador, Ministry of Justice and Public Security; Honduras, Office of Security of the Secretary of State; General Management of the National Police of Honduras; Mexico, Secretariat of Security and Civilian Protection; United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs; UN Office on Drugs and Crime; Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN

Root causes of conflict include the many inequalities (of income, land ownership, access to basic services, race, geography to name a few) that permeate the region’s societies and development models, compounded by institutional fragilities and governance flaws. The coronavirus pandemic’s devastating health, human and economic toll on the region simultaneously exacerbated social tensions and socio-economic inequalities while reinforcing gangs’ legitimacy and further weakening government effectiveness.3 This is likely to aggravate violence and instability in the medium term.

Regional Trends

Continued violence

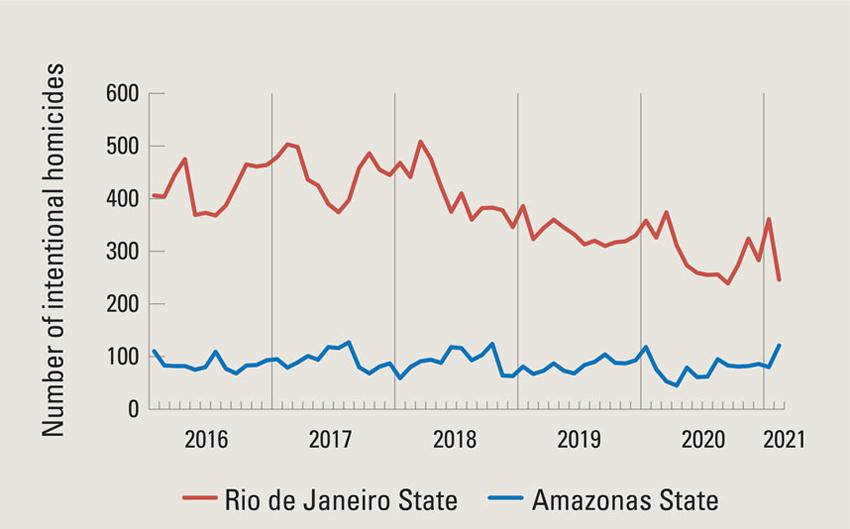

Conflict continued unabated in 2020 and early 2021, despite some initial coronavirus-related disruptions to the activities of criminal gangs.4 Homicide rates decreased notably in El Salvador, and to a lesser extent in Honduras, Colombia, Mexico and Brazil, but this was likely linked to pandemic-related mobility restrictions and other factors – including data-collection flaws as well as arrangements/truces with gangs – and not indicative of an improvement in violence trends.5 Indeed, the decline in homicides was concomitant to spikes of violence in areas of contestation and increases in massacres and killings by security forces across the region.

Sources: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), www.acleddata.com; Thomas Hale et al., ‘A Global Panel Database of Pandemic Policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker)’, Nature Human Behaviour, vol. 5, no. 4, April 2021, pp. 529–38

Economic and social upheaval

The pandemic, coupled with hurricanes Eta and Iota which brought havoc in Central America in November 2020, substantially aggravated underlying root causes of violence in the region.6 Despite most Latin American countries adopting emergency cash transfers to the most vulnerable segments of their populations, poverty rates are estimated to have increased from 30.5% of the regional population to 33.7% in 2019–20, with an additional 22 million people falling into poverty, the worst levels since 2008 (or since 2009 in the case of extreme poverty).7 This further undid progress to reduce inequalities, as shown by an estimated 3% increase of the regional Gini index.8 Employment indicators also worsened, both in terms of unemployment numbers and quality of jobs. Informal workers (including migrants) and youth were among the most affected, boosting the size of the recruitment pool for criminal organisations. Border closures between countries in the region (and with the US) temporarily halted migration, removing a traditional escape valve for countries (notably in Central America) in times of economic hardship.

State inefficiency and growing politicisation of criminal groups

Governments, whose resources and efficiency were significantly stretched by the multiple emergencies, proved increasingly incapable of performing their basic functions. Criminal groups skilfully leveraged the resulting governance gaps to expand and reinforce their territorial control while gaining legitimacy with local populations by providing basic services and essential goods during lockdowns. This reinforced pre-existing trends of politicisation of criminal groups, whose goals to infiltrate or even replace the state became more prominent.

Regional Drivers

Political and institutional

State fragility:

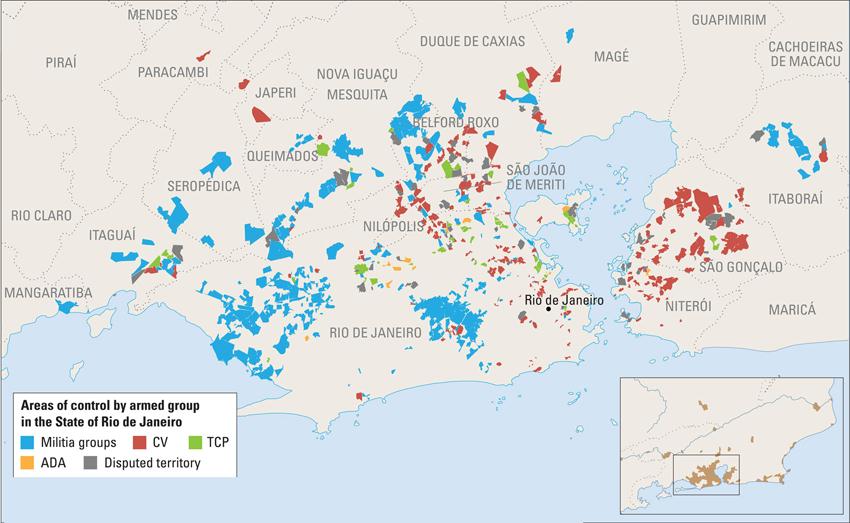

Widespread governance flaws and rampant corruption in the region have historically created a conducive environment for impunity, crime and violence to thrive. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index 2020 classified most countries in the region as either flawed democracies (including Brazil, Colombia and Mexico) or hybrid regimes (including El Salvador and Honduras).9 Institutional limitations have also allowed criminal groups to operate freely and impose their rule in large portions of national territories. In deprived neighbourhoods in Brazil, El Salvador and Honduras, where state governance is poor, criminal gangs impose their own social rules, security measures and illegal taxation schemes. In Mexico, cartels use bribery and violence against public officials to extract favours or impunity. Meanwhile, impenetrable territories in the forest of Colombia create safe havens for coca cultivation and insurgent groups far from the state’s reach.

Economic and social

Socio-economic divides:

Violence has marked the modern history of Latin America. Land disputes embedded in strong socioeconomic divides between rural and urban areas bolstered insurgency in the 1960s. Peace agreements were eventually reached in Nicaragua (1987), El Salvador (1992), Guatemala (1996) and Colombia (early 1990s and 2016) and guerrillas demobilised, but violence soon re-ignited amid continued economic stagnation. Similar pressing social and economic issues also triggered a surge in criminality in countries hitherto unaffected by armed conflict, including Brazil and Mexico, as many in need turned to illicit economies as a source of income. Despite improvement in the last two decades, poverty levels and inequality remain very high in Latin America. By the 2010s, rapid urbanisation,10 in a context of inequality and economic deprivation, further catalysed violence.11 Around 25% of the urban population in Latin America and the Caribbean is poor, and widespread informality and unemployment (especially for youth) provide the perfect terrain for criminal gangs and illicit activities to thrive.12

Drug-trafficking routes and territorial control:

In the late 1990s, drug production and trafficking established itself as a key root of conflict, with certain countries as well as national and transnational criminal groups playing specific roles in the drugs supply chain, further embedding violence in the region. In South America, most notably Colombia, coca cultivation rose dramatically as guerrillas and paramilitaries expanded their territorial control across the country. Honduras, and later El Salvador, increased their role in the transportation of cocaine between South and North America, progressively consolidating their position as transit countries.13 Mexican cartels assumed control of the final narcotics delivery into the US after the dismantling of the largest Colombian cartels. In Brazil, the second-largest market for cocaine after the US, urban gangs consolidated control over the domestic trade of imported cocaine, mostly from Colombia.14 As Brazilian gangs grew in strength and connections, they diversified their activities into cocaine trafficking to Europe, Africa and Asia.

Security

War on drugs:

The adoption of repressive drugs policies across the region, predominantly based on increased militarisation and eradication of illicit crops (including controversial aerial fumigation practices) has also fuelled conflict between state forces and criminal groups, while augmenting alienation among parts of the population (notably farmers and the rural poor). Repressive drugs policies also had the unintended consequence of reinforcing the territorial control and economic power of criminal groups by inducing higher retaliation capacity to confront state forces. The so-called war on gangs declared in El Salvador and Honduras in 2003 increased the defensive and offensive capacity of criminal groups, boosting their ability to hold territory and economic power. In Mexico, under the war on drugs declared by President Felipe Calderón in 2006, drug cartels morphed from a relatively contained business with limited geographical scope and low intensity of violence to a fragmented but organised network of criminal groups. This paved the way for increased violent confrontations and territorial disputes between cartels and against state forces. In Colombia, the implementation of the Plan Colombia in 2000 quickly escalated clashes between the army and guerrillas.15

Regional Outlook

Prospects for peace

The complex nature of conflict in the region, where the line between organised crime and political violence is blurred, will continue to weigh down prospects for durable peace.

Peace achieved through negotiation with nonstate armed groups will remain unlikely in 2021 given the difficulty of engaging myriad actors with different agendas and loyalties, often in conflict with one another, and the legal constraints of negotiating with criminal actors. In El Salvador, the Bukele administration’s continued erosion of checks and balances could enable further negotiations with the Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) gang, after an alleged truce was brokered in 2020. Even under this scenario, however, an escalation of violence in the short term cannot be ruled out as the two sides try to boost their bargaining power.

A continuation of iron-fist approaches to tackling organised crime is likely in Brazil and Colombia amid increased popular concerns about security in the run-up to general elections in 2022 in both countries. Peace in Mexico will remain elusive amid shifting balances of power and areas of contestation among criminal groups.

Escalation potential and spillover risks

The social and economic damage from the coronavirus pandemic and hurricanes Eta and Iota in Central America, coupled with an unprecedented political and economic crisis in Venezuela and increasing political instability in the region, point to a worsening conflict landscape and highlight some additional areas of fragility to watch. Climate change, which is particularly impacting the Dry Corridor in Central America, will be another multiplier of conflict in the medium to long term.

Deteriorating socio-economic conditions and increasingly limited fiscal space to provide support for vulnerable populations will drive greater numbers towards criminal groups or migration, in turn creating new business opportunities for illicit actors and threatening domestic and regional stability across Central America, the US border with Mexico, and the border regions between Colombia and Venezuela.16 Venezuela and Haiti, both mired in deepening political crisis, spiralling crime and collapsing institutions, represent other potential sources of conflict, with important regional spill-overs in terms of migration and violence.

The delayed roll-out of COVID-19 vaccinations in the region underscores the likelihood of additional lockdowns in the year ahead. This will add to existing socio-economic strains and further weaken state legitimacy to the benefit of criminal groups. Likely strong demand for drugs – especially for cocaine in the US and Europe – will continue to drive illegal economies in the region and competition among criminal organisations for territorial control, which will sustain violence.

Geopolitical changes

Developments in the US, Colombia and Venezuela will continue to determine conflict trends in the region. US policies on drugs, access to firearms and migration will remain the main geopolitical influencer. In early 2021, the administration of Joe Biden pledged a US$4 billion four-year aid package to address root causes of migration in the Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras), namely poverty, lack of economic opportunities, corruption and climate-related issues. While this could improve these countries’ outlook and governance in the medium to long term, it is unlikely to substantially curb migration flows in the short term; in fact, expectations of a more favourable migration policy will probably attract more migrants in the short term. Moreover, the Biden administration’s focus on corruption will complicate cooperation with Central American governments given the deterioration in the rule of law across the region in recent years. It is also unlikely that the US will deviate substantially from its traditional repressive drugs policies, as suggested by Biden’s support for Colombia’s decision to restart its aerial coca-eradication programme in early March 2021.

Colombia’s role as a global supplier of cocaine makes its security policy another key determinant of the regional violence outlook. While general elections in 2022 may herald some changes in this realm, the incumbent government is almost certain to continue its iron-fist security policy and discourse while it remains in office to retain the support of its core constituency. Lastly, the crisis in Venezuela, with its migrant outflows, its rampant illicit economies and the protection it affords to various Colombian non-state armed groups, will continue to affect dynamics of regional stability. Moreover, the country forms the main theatre for great-power competition in the region, featuring different forms of involvement from China, the European Union, Iran, Russia, Turkey and the US. Substantive progress towards breaking the political impasse and the organisation of free and fair elections seems doubtful in the short term amid irreconcilable negotiation positions from President Nicolás Maduro and acting president Juan Guaidó, a fragmented opposition and low appetite from Biden to use his domestic political capital to push for a negotiated solution. His Venezuela policy will likely resemble his predecessor’s, based on sanctions for the Maduro regime and full support for Guaidó.

Notes

- 1 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, ‘Gang Violence: Concepts, Benchmarks and Coding Rules’.

- 2 Liberal policies on arms possession in the US have been another driver of violence, providing criminal organisations across the border in Mexico easy access to weapons. See Parker Asmann, ‘Lack of US Gun Control Provokes Record Bloodshed in Mexico’, InSight Crime, 31 August 2019.

- 3 Latin America has been the region worst affected by the pandemic, against a backdrop of high levels of urbanisation and informality (60%), underdeveloped social-security nets, and fragmented and underfunded healthcare systems. Although home to only around 8% of the global population, it accounted for almost 20% and 30% respectively of total active cases and deaths in the world as of the end of 2020, with Brazil and Mexico ranking second and fourth globally for fatalities. According to the IMF, Latin American GDP contracted by 7% in 2020, the worst performance across the world’s regions. See Antonio David, Samuel Pienknagura and Jorge Roldos, ‘Latin America’s Informal Economy Dilemma’, Diálogo a Fondo; Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, ‘Social Panorama of Latin America 2020’, March 2021, p. 13; World Health Organization, ‘WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard’; International Monetary Fund, ‘World Economic Outlook Database’, April 2021.

- 4 When the strongest lockdown measures were in force in El Salvador, Honduras and Colombia (between April and August 2020) and Mexico (in December 2020 and January 2021), significant monthly spikes in conflict-related fatalities (namely battles, explosions/remote violence and violence against civilians, according to ACLED) were reported, signalling the rapid reactional and operational capacity of criminal groups to challenge state authority.

- 5 A truce was widely alleged to explain the substantial dip observed in El Salvador, where the murder rate halved year on year to 19.7 per 100,000. See Parker Asmann and Katie Jones, ‘InSight Crime’s 2020 Homicide Round-Up’, 29 January 2021.

- 6 Duncan Tucker and Encarni Pindado, ‘When it Rains it Pours: The Devastating Impact of Hurricanes Eta and Iota in Honduras’, Amnesty International, 13 December 2020.

- 7 Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, ‘Social Panorama of Latin America 2020’, Graphic 1, p. 15.

- 8 Ibid, p. 28.

- 9 Only three countries in the region were considered ‘full democracies’, while a further three were classed as ‘authoritarian regimes’. See Economist Intelligence Unit, ‘Democracy Index 2020: In Sickness and in Health’.

- 10 With 81% of its population living in cities, Latin America is currently the most urbanised region in the world. See Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, ‘Social Panorama of Latin America 2020’, p. 16.

- 11 In 2013, for example, 84% of the 50 most violent cities (including the top 16) in the world were in Latin America and the Caribbean. World Bank, ‘Stopping Crime and Violence in Latin America: A Look at Prevention from Cradle to Adulthood’, Results Briefs, 17 May 2018.

- 12 Natalie Alvarado and Robert Muggah, ‘Crime and Violence: Obstacles to Development in Latin America and Caribbean Cities’, Inter-American Development Bank, November 2018, p. 2.

- 13 In 2010, Honduras was classified as a major drug-transit country by the United States government, followed by El Salvador in 2011. According to the US Department of State, by 2015, 90% of cocaine on the US market had first transited through the Central America–Mexico corridor. See US Department of State, Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, ‘International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, Volume I: Drug and Chemical Control’, March 2016, p. 161.

- 14 Alongside cocaine and marijuana, more recently synthetic drugs have also been part of drug-trafficking operations.

- 15 Plan Colombia, adopted in 2000, primarily aimed to end the conflict in Colombia by supporting the Colombian armed forces (through funding and training) to eradicate drug trafficking.

- 16 All seven of Colombia’s departments bordering Venezuela have seen the presence of multiple criminal groups. Some of them move across extensive areas on both sides of the border, including Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) dissident units such as the Second Marquetalia. At least 70% of the National Liberation Army’s forces are located in the borderlands. While clashes between dissidents from the FARC, the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the Venezuelan army in Venezuela’s border regions and sporadic incursions of the latter into Colombian territory will continue in the year ahead, it is unlikely that political tensions between Colombia and Venezuela will result in a full-fledged military confrontation. See International Crisis Group, ‘Disorder on the Border: Keeping the Peace between Colombia and Venezuela’, Report No. 84, 14 December 2020.

MEXICO

Source: Mexico, Ministry of Finance and Public Credit

Overview

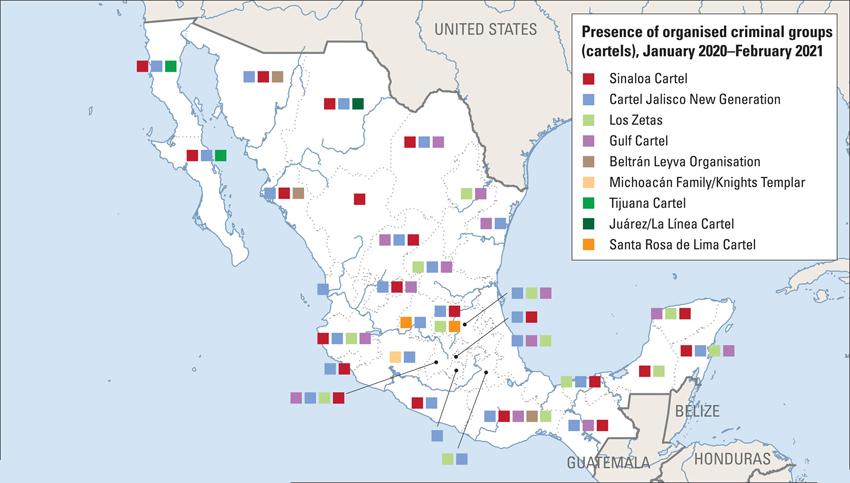

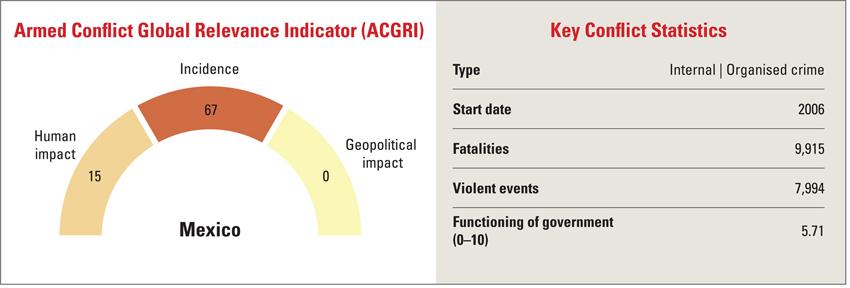

Mexican drug-trafficking organisations (DTOs) originated in the 1970s, serving as intermediaries trafficking cocaine from South America to the United States, in addition to producing drugs (primarily marijuana) locally. At the time, operations were largely controlled by the Guadalajara Cartel led by Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo. After his arrest in 1989 – following the murder of a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agent in Mexico – the territory it had controlled was split between four major DTOs run by Félix Gallardo’s closest associates, namely the Sinaloa, Juarez, Tijuana and Sonora cartels, an arrangement that largely persisted for the next 15 years. Drug-related violence began escalating following the 2000 electoral defeat of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), after seven decades of continuous rule, which undid many existing unofficial agreements between the DTOs and the government. Numerous high-profile acts of violence led President Felipe Calderón (2006–12) to launch the war on drugs in December 2006, triggering a full-scale (ongoing) confrontation between state security forces and the DTOs. Of the 19 DTOs identified by the government, 11 operate in more than one state and two – the Sinaloa Cartel and the Cartel Jalisco New Generation (CJNG) – have a presence in every state of Mexico as well as strong international operations.

Despite restrictions caused by the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, violence showed little respite, with 35,484 intentional homicides recorded (or a homicide rate of 22.6 per 100,000). This represented a modest decrease of 0.4% compared to 2019’s record number of absolute and relative homicides in Mexico.1 Although the decrease reversed the continuous annual increases witnessed since 2014, it cannot yet be established whether it represented the beginning of a structural downward trend akin to the 2011–14 period.

During 2020, the government reinforced its existing strategy of combatting DTOs through the National Guard (GN), a gendarmerie-style force created in 2019 specifically to deal with cartel violence and fulfil a campaign promise by current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador to demilitarise the war against DTOs. The GN was involved in virtually every major operation against DTOs in 2020 and by the end of the year had become the second-largest security force in the country.

However, the lack of substantive security advances translated into relatively high public disapproval levels for López Obrador’s security policy, which throughout 2020 was among the most consistently poorly rated policy areas.

Conflict Parties

Secretariat of National Defence (SEDENA) – (Army and Air Force)

Strength: 165,500.

Areas of operation: Across the whole country but concentrates its forces in the north and the Pacific region: in Baja California, Chihuahua Coahuila, Jalisco, Guerrero, Michoacán, Sonora and Tamaulipas.

Leadership: General Luis Crecencio Sandoval (head of SEDENA); General Manuel de Jesús Hernández González (head of the air force).

Structure: SEDENA forms one branch of Mexico’s two defence ministries. The army is divided into 12 military regions and 46 military zones. The air force is divided into four air regions. The General Staff of National Defence is divided into eight sections, of which the second section (intelligence) and the seventh section (combatting drug trafficking) focus on DTOs.

History: The Ministry of War and the Navy was created in 1821 to supervise the army, navy and air force. In 1939 it was divided to create SEDENA and the Secretariat of the Navy (SEMAR).

Objectives: Provide internal security and fight drug trafficking.

Opponents: DTOs.

Affiliates/allies: SEMAR, GN and special-forces combat group GAIN (Drug Trafficking Information Analysis Group), which is in charge of capturing DTO leaders. Also supported by the National Intelligence Centre (CNI) and the Attorney General’s Office, as well as foreign governments through cooperation programmes (e.g. the Mérida Initiative with the US).

Resources/capabilities: Infantry, armoured vehicles and combat helicopters. 2020 budget: US$5.5 billion (approximately MXN 118bn).2

Secretariat of the Navy (SEMAR)

Strength: 50,500.

Areas of operation: The country’s coasts, divided into the Pacific and Gulf of Mexico–Caribbean zones.

Leadership: Admiral José Rafael Ojeda Durán.

Structure: Divided into General (70%) and Naval Infantry Corps (marines; 30%), which operate in eight naval regions and 18 naval zones (12 in the Pacific and six in the Gulf and Caribbean). The marines’ special forces also combat criminal groups in the country’s interior.

History: Created in 1821. SEMAR separated from SEDENA in 1939.

Objectives: Defend Mexico’s coasts, strategic infrastructure (mainly oil platforms in the Gulf of Mexico) and the environment at sea, and fight piracy.

Opponents: DTOs, particularly those that traffic people through the coasts, from South and Central America, and those that transport drugs via sea from Colombia and Venezuela.

Affiliates/allies: SEDENA, GN and CNI. Cooperates with US Coast Guard at the border.

Resources/capabilities: Fast vessels for interception, exploration and intelligence; supported by naval aviation. 2020 budget: US$1.63bn (approximately MXN 35bn).

National Guard (GN)

Strength: 92,100.

Areas of operation: Across the whole country. The states of Guanajuato, Jalisco, Mexico, Michoacán, Oaxaca and Sinaloa had the highest number of operational coordination regions at the end of 2020.

Leadership: Alfonso Durazo (secretary of public security and citizen protection (SSPC)); General (Retd) Luis Rodríguez Bucio (commander).

Structure: A total of 266 coordination regions expected to be operational by the end of 2021. 200 of these were operational as of 31 December 2020.

History: Began operating in May 2019, by presidential order. The law gave GN personnel the authority to stop suspected criminals on the streets.

Objectives: Reduce the level of violence in the country and combat DTOs.

Opponents: DTOs and medium-sized criminal organisations.

Affiliates/allies: SEDENA, SEMAR, and local and municipal police.

Resources/capabilities: Acquired resources from the defunct Federal Police, including their helicopter teams and equipment such as assault rifles. Relies on intelligence from SEDENA, SEMAR and the CNI.

Sinaloa Cartel (CPS)

Strength: Unknown.

Areas of operation: Headquartered in Culiacán, Sinaloa, but with a presence in all 32 states of Mexico. Outside Mexico, active in Asia, Canada, Central America and Europe. In the US, it has an important presence in California, Colorado, Texas and New York.

Leadership: Historical leader since the mid-1990s, Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán was captured in 2016 and imprisoned for life in the US in 2019. His number two, Ismael ‘El Mayo’ Zambada García, is in a leadership struggle with El Chapo’s sons, Ovidio and Iván Archibaldo.

Structure: Hierarchical organisation, with three sub-divisions: finance/business, logistics for drug transportation and military structures.

History: Preceded by the Guadalajara Cartel, co-founded in the late 1970s by leader Rafael Caro Quintero. In the 1990s, following the peace processes in Central America, the large-scale ground transit of cocaine began. In the mid-1990s, El Chapo became leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, opened routes from Guatemala to Mexico and the Tijuana route, and forged alliances with the Medellín Cartel in Colombia. Focused for 20 years on cocaine, but now diversifying into heroin, methamphetamine and fentanyl.

Objectives: Control all drugs markets (for cocaine and methamphetamine in particular), including production networks in Colombia, distribution in Central America and Mexico and consumption in the United States.

Opponents: Other DTOs, including the Gulf Cartel, the Tijuana Cartel and the Juarez Cartel. SEMAR, SEDENA’s intelligence section and special forces. The US DEA and Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA).

Affiliates/allies: Many subordinate medium-sized and small DTOs, at the regional level, including cocaine-producing partners in Colombia. Partners with many corrupt Mexican government officials. A large number of Sinaloa governors are suspected of supporting the cartel.

Resources/capabilities: High-powered weapons, such as the Barrett M107 sniper rifle and anti-aircraft missiles, and a large fleet of drug-transport planes.

Cartel Jalisco New Generation (CJNG)

Strength: Unknown.

Areas of operation: Headquartered in the state of Jalisco, with a presence in most states, particularly Colima, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Jalisco, Michoacán and Nayarit. It also controls the Pacific ports of Manzanillo and Lazaro Cardenas, where chemicals from China enter Mexico. It has rapidly expanded in the US, where it is thought to have a presence in 35 states and in Puerto Rico.

Leadership: The main leader is Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, commonly known as ‘El Mencho’.

Structure: El Mencho successfully co-opted all regional leaders of the Michoacán Family and the Knights Templar to control the laboratories in the Michoacán mountains.

History: Formed in 2011 in Guadalajara, Jalisco, CJNG initially produced methamphetamine in rural laboratories in Jalisco and Michoacán. In 2012–13, it expanded to Veracruz. Since 2015–16 its influence has grown throughout the country, thanks in part to gaps left after the government successfully targeted other DTOs (such as the Michoacán Family, the Knights Templar, Los Zetas and the Sinaloa Cartel).

Objectives: Fully replace the Sinaloa Cartel at the helm of Mexico’s criminal networks.

Opponents: Sinaloa Cartel, Los Zetas, the special forces of SEMAR and SEDENA.

Affiliates/allies: Demobilised members of the Michoacán Family and the Knights Templar, as well as large numbers of collaborating peasants.

Resources/capabilities: Estimated capital of US$1bn from the sale of methamphetamine and fentanyl as well as the extortion of merchants and money-laundering activities in Guadalajara.

Los Zetas

Strength: Unknown. Hit hard by the government between 2012 and 2016.

Areas of operation: Tamaulipas State, mainly along the border with Texas, as well as Coahuila, Nuevo León, Veracruz, Tabasco and the area along the border with Guatemala.

Leadership: Founded by Heriberto Lazcano, former member of the Mexican army. Since 2013, 33 of its main leaders (including Lazcano) have been arrested or killed in combat by military forces.

Structure: Horizontal, decentralised structure that works as a large business with multiple criminal activities. Unsuccessful at drug trafficking, its cells carry out extortions and kidnappings, collect criminal taxes from merchants and traffic migrants from Central America to Texas.

History: Originally the armed wing of the Gulf Cartel, drawing most of its members from the Mexican and Guatemalan armies. Notorious for perpetrating mass violence against the civilian population and migrants. Between 2010 and 2012, a major SEMAR offensive to dismantle the ‘Gulf Corridor’ weakened the group significantly. It is the DTO against which the Mexican government has been most successful.

Objectives: Control criminal activity in the Gulf of Mexico states.

Opponents: CJNG, Gulf Cartel and the special forces of SEMAR.

Affiliates/allies: Criminal networks in Tamaulipas State.

Resources/capabilities: Migrant smuggling and criminal taxes on merchants.

Gulf Cartel

Strength: Unknown.

Areas of operation: Operates and controls territories in Tamaulipas State, particularly the border area with Texas, including strategic border cities, such as Nuevo Laredo, Reynosa and Matamoros.

Leadership: The current leader is Homero Cárdenas Guillén. Many former leaders have been killed in combat or detained and extradited to the US.

Structure: Unstable, with fragmented leadership.

History: The second-oldest DTO in the country, smuggling alcohol, weapons and drugs across the US border since the 1940s. After forging a partnership with the Colombian Cali Cartel in the 1990s, the group focused on introducing cocaine to the US market. Los Zetas violently separated from the group in 2010.

Objectives: Smuggle drugs on the Texas–Tamaulipas border and control drug trafficking in northeast US.

Opponents: Los Zetas, CJNG and the special forces of SEMAR and SEDENA.

Affiliates/allies: Closely linked to Tamaulipas State’s governors (three former governors have been charged in Texas) and criminal networks.

Resources/capabilities: Many Tamaulipas businessmen support the cartel in laundering money.

Beltrán Leyva Organisation

Strength: Unknown.

Areas of operation: Mainly in the states of Guerrero and Morelos, and the Mexico City–Acapulco highway. The group controls poppy production and the export of heroin from Iguala (Guerrero) to Chicago, IL.

Leadership: Founded by brothers Arturo, Alfredo, Carlos and Héctor Leyva – Arturo was killed in 2009 and the other three were imprisoned, with Héctor dying in 2018.

Structure: Based around vertically organised cells. After the death or imprisonment of the four brothers, seven local criminal groups emerged in Guerrero State: the Ardillos, the Granados, the Independent Cartel of Acapulco (CIDA), the Mazatecos, the Rojos, the Ruelas Torres and the United Warrios (GU).

History: A breakaway group of the Sinaloa Cartel formed in 2008 in Sinaloa before moving to the South Pacific–Acapulco (Guerrero State), Morelos and Mexico State.

Objectives: Control heroin trafficking in the South Pacific and from Mexico to Chicago.

Opponents: Sinaloa Cartel, CJNG and the special forces of SEDENA.

Affiliates/allies: An estimated 100,000 peasants who grow poppies in Guerrero.

Resources/capabilities: Profits from the sale of heroin in the US and from criminal activities such as extortion and kidnapping in Mexico.

Michoacán Family/Knights Templar

Strength: Unknown.

Areas of operation: The surviving criminal cells moved to Guanajuato, Guerrero and Mexico State.

Leadership: Fragmented following the 2015 arrest of Servando Gómez Martínez.

Structure: Organised into independent cells.

History: Gained power by producing methamphetamines, importing chemical precursors from China. Founded by Nazario Moreno Gonzalez in 2005, the organisation’s initial recruitment was based on a religious discourse. Between 2006 and 2012, the group built a broad network of collaborators among the population, gained control of a large number of local politicians on the Pacific coast of Michoacán and ran methamphetamine labs in the mountains. However, it was practically dismantled by Mexican government forces between 2013 and 2016. Following the capture of its first leaders, the Michoacán Family became the Knights Templar in 2013–14, under the leadership of Servando Gomez.

Objectives: Control mining and agricultural production (of avocados for export to the US) in Michoacán State; control the port of Lazaro Cardenas (for smuggling the chemical base for producing methamphetamine); and steal fuel in Guanajuato State.

Opponents: Sinaloa Cartel, CJNG, Los Zetas and the special forces of SEDENA.

Affiliates/allies: A large number of collaborating peasants.

Resources/capabilities: The revenue from criminal taxes on many economic activities.

Tijuana Cartel (also known as Arellano Felix Family Organisation)

Strength: Exact numbers unknown, but thought to have regained some strength since 2018.

Areas of operation: A bi-national, cross-border organisation operating between Tijuana, Baja California and San Diego, CA; Los Angeles, CA.

Leadership: Fragmented as Benjamin Arellano Felix and his brothers Ramón, Eduardo, Luis Fernando, Francisco, Carlos and Javier are all imprisoned in California jails.

Structure: Groups of young people either become gunmen or cocaine exporters (middle-class youth who have visas to cross the border). Their leaders are family members.

History: During the 1980s and 1990s, the Arellano Felix brothers controlled the north of the country and transported drugs across the border through tunnels, migrants and people moving on foot or by car.

Objectives: Control drug trafficking from Baja California to California, US.

Opponents: Sinaloa Cartel, the special forces of SEDENA and US intelligence services cooperating with Mexican authorities at the border.

Affiliates/allies: Many people cross the border daily with small amounts of drugs.

Resources/capabilities: Revenue from the crossborder cocaine trade.

Juarez Cartel/La Línea

Strength: Unknown.

Areas of operation: A bi-national, cross-border organisation active in North Chihuahua and North Sonora in Mexico and Southwest Texas; Las Cruces and Albuquerque, NM, and Tucson, AZ, in the US.

Leadership: Founded by Amado Carrillo Fuentes in the 1990s. His brother Vicente Carrillo Fuentes directs it from prison.

Structure: Three local cartels in Ciudad Juárez: La Línea, Los Artistas Asesinos and Los Aztecas, which clash over cocaine shipments to be exported to El Paso, TX.

History: Amado Carrillo Fuentes, the ‘Lord of the Skies’, orchestrated the smuggling of drugs in small planes at low altitude, which went undetected by radars. In 2009 it began to fight with the Sinaloa Cartel for control of the Central Mexican and the US-highway trafficking routes.

Objectives: Control drugs crossing from Ciudad Juárez to El Paso, and into New Mexico and Arizona, and drug trafficking to northeast US.

Opponents: Los Zetas, CJNG, the special forces of SEDENA and the DEA.

Affiliates/allies: Groups of young people either become gunmen or drugs-exporters (middle-class youth who have visas to cross the border).

Resources/capabilities: The proceeds from drug trafficking.

Santa Rosa de Lima Cartel (CSRL)

Strength: Exact numbers unknown but experienced large-scale arrests in 2019–20.

Areas of operation: Guanajuato; minor operations in neighbouring states including Queretaro and Hidalgo.

Leadership: Founded by David Rogel Figueroa ‘El Güero’ in 2014 and from 2017 led by José Antonio Yépez Ortiz ‘El Marro’. Unclear leadership structure following El Marro’s arrest on 2 August 2020 though the organisation is highly family oriented.

Structure: Organised into numerous regional cells. One cell known as the Shadow Group was previously associated with the Gulf Cartel. Many high-level operatives (including financial operatives) are relatives of El Marro.

History: Formed in 2014 as a huachicolero (fuel theft) gang in the state of Guanajuato and grew to a fully fledged DTO after 2017 when El Marro assumed leadership, expanding its operations to include drug trafficking, retail drug trade, kidnapping and extortion. Significantly weakened since 2019 because of the government’s campaign against fuel theft as well as conflict with the CJNG, which has contested its dominance in the state.

Objectives: Control the fuel-theft market in the Bermuda Triangle area of Guanajuato as well as supplementary resources through drug trafficking (mainly cocaine) and other illegal activities in that area.

Opponents: CJNG, GN, other SEDENA and SEMAR forces.

Affiliates/allies: Local fuel-theft gangs.

Resources/capabilities: The proceeds from fuel theft and other drug-trafficking revenues. Fuel-theft income has fallen significantly since 2019 and it is believed the group is severely weakened, having possibly lost around 40% of its manpower.3

Conflict Drivers

Political

Institutional corruption and impunity:

Mexico has traditionally suffered from high levels of corruption and impunity, enabled by a permissive political culture as well as lax law enforcement. Mexico ranked 124th worldwide and second worst (only above Venezuela) among Latin America’s seven biggest economies in the 2020 Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.4 Against this backdrop, DTOs have found it easy to bribe or intimidate public officials, particularly targeting municipal-level officials given the lack of protection offered to them and the underfunding and underarming of municipal police forces. An estimated 264 mayors, mayoral candidates and former mayors were murdered by DTOs between 2002 and 2019.5 Higher-profile officials have also been targeted, including, for example, a district-court judge, Uriel Villegas Ortiz, in June 2020, the first killing of a federal judge since 2016, and the former governor of Jalisco, Aristóteles Sandovla, in December 2020, the highest-ranking public official killed since the drug war began.

Economic and social

Poverty and precarity:

Widespread poverty and precarious labour conditions among Mexico’s youth (around a quarter of the population) contributes a constant supply of manpower for DTOs. An estimated 48.8% of Mexico’s population (61.1m people) lived under the national poverty line in 2018,6 a figure that has not improved significantly since the 1990s and which highlights the poor future prospects for many young people as social mobility is also limited. This bleak economic picture increases the appeal of joining a DTO, as the potential income far outstrips that offered by most legal employment, despite the risk of death or imprisonment. Informal employment is high at 55.8% of the labour force,7 facilitating money laundering and other financial crimes driven by DTOs.

It is also estimated that around 35–45,000 Mexican children may be involved to some degree with DTOs, usually as lookouts but even as hitmen, while girls are frequently coerced into the sex trade.8

Geography:

Mexico’s location, situated between the main source of cocaine production (South America) and the main consumption market for all drugs (the US), triggered its emergence as a major drug-trafficking centre. Mexico is also a major drugs producer in its own right, being the largest producer of opium in the Western Hemisphere with an estimated 6% of the global supply (only behind Afghanistan and Myanmar) as well as the second-largest marijuana producer in the world (behind Afghanistan).9 Mexico is also a major producer of synthetic drugs such as methamphetamine, and a transit route for fentanyl from China, where most of it is produced, into the US.

The so-called Golden Triangle region which encompasses the states of Sinaloa, Chihuahua and Durango is estimated to account for as much as three-quarters of Mexico’s cultivated drug production. Jalisco and Michoacán are in turn the primary centres of synthetic-drugs production, leveraging precursor chemicals illegally imported from Asia through the ports of Lázaro Cárdenas and Manzanillo.

International

US drug demand and policy:

The market conditions driving the prevalence of DTOs in Mexico stem from the US demand for illegal drugs (estimated by some sources to be nearly US$150bn annually). DTOs are also able to easily obtain assault rifles and other weapons in the US and smuggle them across the border to Mexico, usually in small but steady quantities which are difficult to detect, in so-called ‘ant trafficking’. US drug policy has largely supported the military strategies adopted by successive Mexican governments to combat DTOs. This, in turn, has precluded discussion of potential alternative approaches such as more widespread legalisation of drugs (including some hard drugs), or negotiations between government and the DTOs.

Political and Military Developments

The fight against financial crime

The López Obrador administration considerably strengthened the scope of operations of the Financial Intelligence Unit (UIF) of the secretariat of finance tasked with investigating money laundering and terrorist financing. During 2020, the UIF froze a total of 19,970 financial accounts related to organised crime, compared to 800 in 2018.10 These accounts amounted to a total of US$372.3m (MXN $8bn) in assets, compared to US$244.2m (MXN $4.7bn) frozen in 2019 and dwarfing the US$3.6m (MXN $69.7m) in 2018. This rise in overall asset seizures suggests a stronger commitment to attacking DTO finances than previous administrations.

Arrest and exoneration of General Cienfuegos

On 15 October 2020, Mexico’s former secretary of defence, General Salvador Cienfuegos, was arrested in the US on drug-trafficking and money-laundering charges. The López Obrador government, which had not been informed of the investigations, reacted strongly and managed to negotiate Cienfuegos’s extradition to Mexico. In an unprecedented move, announced as a measure to strengthen bilateral security cooperation, all charges were dropped in November so that Cienfuegos could be transferred to Mexican custody. In January 2021, Cienfuegos was exonerated by Mexico’s attorney general’s office amid allegations of government interference in the investigation. However, the DEA’s evidence against Cienfuegos was found to be riddled with translation errors which undermined their case.

Source: Press conference by Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, 31 December 2020

New proposed regulation of foreign security officials

At the end of 2020, in what was widely seen as a response to Cienfuegos’s arrest, a reform was proposed to the National Security Law to regulate foreign law-enforcement officials operating in Mexico. The law would remove diplomatic immunity for foreign agents operating in Mexico and force them to share all information regarding ongoing investigations with their Mexican counterparts and would force Mexican officials to report all communications with foreign agents to the government. The reform was fast-tracked in the Senate on 9 December and in the Chamber of Deputies on 17 December, however López Obrador eventually had the law watered down before its final approval on 14 January 2021 to exclude the sharing of confidential information and to remove restrictions to electronic communications.

Continued militarisation of the fight against crime

A presidential decree signed in May 2020 allowed the armed forces to continue participating in public-security duties, as a complement to the GN, until 2024, in a further manifestation of the higher prominence of the military in public life under López Obrador compared to previous administrations. In July, the military was also tasked with administering Mexico’s ports and customs, many of which have been significantly infiltrated by organised crime.

Focus on Guanajuato

José Antonio Yépez Ortiz, the leader of the CSRL, was captured in August 2020 in a combined operation involving federal and state police forces and the GN. The most important arrest of a major DTO leader in 2020, it highlighted the growing importance of Guanajuato State in Mexico’s drugs war. Once one of Mexico’s safest states and a major manufacturing hub, since 2018 it had become one of the most violent: in 2020 its homicide rate was the second-highest nationwide (72.1 per 100,00).11 The biggest mass killing of 2020 occurred in Guanajuato in July when CSRL gunmen stormed a drug rehabilitation centre in Irapuato, killing 27 people.

Attack against Omar García Harfuch

In June 2020, CJNG gunmen ambushed a vehicle carrying Mexico City’s secretary of public security, Omar García Harfuch, in broad daylight in one of the capital’s most upscale neighbourhoods. Despite being shot several times, García Harfuch survived the attack. A dozen CJNG members were arrested for participating in the attack. Notably, the attackers were carrying military-grade weaponry including a .50-calibre sniper rifle.

Key Events in 2020–21

POLITICAL EVENTS

9 March 2020

‘Day Without Women’ march takes place in response to López Obrador’s lack of attention towards feminicides and gender violence.

23 March

The government imposes social-distancing measures and closes non-essential activities to curb the coronavirus pandemic.

29 March

López Obrador visits Sinaloa and shakes hands with El Chapo’s mother.

April

Large DTOs are seen distributing food and other pandemic-related aid in the absence of government support.

11 May

López Obrador signs a decree enabling the armed forces to continue internal public-security duties until March 2024.

1 June

A new system of state-level pandemic alerts is introduced, allowing states with falling case levels to gradually begin reopening.

1–2 June

The UIF undertakes ‘Operation Agave Azul’, freezing the assets of nearly 2,000 people and companies related to the CJNG.

17 July

López Obrador announces a plan to hand over control of ports and customs to the military to reduce corruption.

15 October

Former secretary of defence Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos is arrested in the US on drug-trafficking and money-laundering charges.

17 November

US drops charges against Cienfuegos ahead of his return to Mexico to face investigation.

19 November

Senate approves marijuana-legalisation bill (following approval in the lower house, Senate will need to vote again).

15 December

Chamber of Deputies approves controversial reform to National Security Law.

18 December

Mexico City and the neighbouring state of Mexico are placed on the highest coronavirus alert level due to rising cases of COVID-19 from a second wave.

14 January 2021

Cienfuegos is cleared of all charges in Mexico. Watered-down version of National Security Law is approved.

MILITARY/VIOLENT EVENTS

16 June 2020

A district-court judge, Uriel Villegas Ortiz, and his wife are murdered in Colima State.

26 June

Omar García Harfuch, Mexico City secretary of public security, is targeted in an assassination attempt by CJNG.

1 July

27 people in a drug rehabilitation centre in Irapuato, Guanajuato State, are murdered by hitmen of the CSRL.

2 August

‘El Marro’, leader of the CSRL, is arrested.

18 December

Aristóteles Sandoval, former governor of Jalisco, is murdered.

Impact

Human rights and humanitarian

Despite López Obrador pledging that it would not, one year after its creation, the GN appeared to have inherited many of the same complaints regarding human-rights abuses levelled at the armed forces and the now defunct Federal Police. Over the course of 2020, the National Commission for Human Rights (CNDH) received 350 human-rights complaints relating to the GN, almost equalling the 359 it received about SEDENA.12 These complaints came from all but one state and involved arbitrary detentions, excessive use of force, intimidation, prevention of access to justice, cruel and degrading acts, torture and forced disappearances. Part of the problem lies in the fact that around half of the GN are former members of the Federal Police and armed forces, with low levels (20% of its members and just 0.3% of new recruits) of vetting on human-rights records and successful completion of police training.13

Many DTOs have branched out into migrant kidnapping, preying on Central Americans attempting to reach the Mexican border and cross over to the US. The 2019 US ‘Remain in Mexico’ policy kept asylum seekers in Mexico while their cases were reviewed by US authorities, which made them a target for DTOs: it was estimated that around 80% of migrants and asylum seekers sent to Mexico to wait for US court hearings were victims of violence in the first nine months of 2019.14

Political stability

The impact of drug-related violence on national domestic political stability was less severe than often perceived by the public or the media, however lower levels of government and certain regions were worse affected. Drug-related violence did not impede the functioning of government and state institutions at a federal level nor cause any interruption to democratic order. Likewise, DTOs rarely targeted high-level federal officials (with some exceptions, like a small number of federal judges). In contrast, state- and municipal-level institutions and officials suffered greatly from DTO threats, bribery and killings, especially in a small number of particularly violent states. Overall, however, the risk of severe political instability caused by DTO-related violence was low, with DTOs seemingly avoiding challenging the state directly.

Economic and social

The impact of DTO violence on economic stability was also relatively minor, given its limited negative effects on productive activity, public services and the functioning of markets. This is despite the considerable overall cost of violence in Mexico, with one estimate putting it as high as 21.3% of GDP, although this included indirect costs such as lost future income from homicides as well as opportunity costs from security spending (direct costs of violence accounted for only about one-fifth of the total).15

The López Obrador administration has recognised the economic factors driving the drug trade, arguing in favour of social development as a longterm solution to crime. In its two years in office, it has already implemented various youth-focused social-assistance schemes and raised the country’s minimum wage considerably more than its predecessors, yet the pandemic-related recession will offset many of these actions, with poverty and labour precarity expected to persist and continue to drive crime.

Conflict Outlook

Political scenarios

Mexico will hold midterm elections on 6 June 2021 which will see the entire Chamber of Deputies up for election, as well as numerous other state and local positions. According to most polls, the ruling party, Morena, remained on course to retain its legislative majority, although it could lose the supermajority that has allowed it to reform the constitution at will. Regardless, there appeared to be few prospects of a change in security policy and most changes that would have required constitutional amendments have already been undertaken. López Obrador did not signal any willingness to change security policy, which will continue to prioritise the GN as the main force to combat the DTOs, despite few major successes to date.

Despite the expansion of the military’s duties into civilian and economic life, it is unlikely that it will make inroads into Mexican politics, given the lack of modern historical precedence and the likelihood of strong public repudiation should the military step out of the bounds set by the executive.

Mexico’s efforts against the DTOs will continue to rely heavily on US assistance, particularly in terms of information sharing: US intelligence has contributed significantly to the capture of major DTO leaders in the last 20 years. However, the controversial reform of the National Security Law and strong US opposition to it will threaten prospects for continued close cooperation.

Escalation potential and conflict-related risks

The dynamics of the drug war in Mexico make it difficult to estimate whether the conflict will intensify during any given year, as much depends on the balance of power between different DTOs, as well as arrests or killings of major DTO leaders causing power vacuums or escalations in violence. One trend that could impact DTOs’ financial power (and therefore their capacity for violence) is the growing importance of the synthetic-drug trade, particularly fentanyl, which benefits from easy production and transportation, and high profit margins. The government has responded by intensifying seizures of these drugs. Fentanyl seizures in 2020 totalled 1,301 kg, which represented a 486% increase compared to the 222 kg seized in 2019. Additionally, a total of 175 clandestine laboratories producing synthetic drugs of all types were dismantled, nearly twice as many as in 2019. 16 Despite the increase in fentanyl seizures, the drug will continue to pose a challenge due to the ease of its illegal and legal importation into Mexico and the widespread use of its chemical precursors in the medical industry, ruling out the possibility of a total ban.

A more positive trend is the potential legalisation of marijuana, already decriminalised by a 2018 Supreme Court ruling. In November 2020, the Senate approved a bill which decriminalised the possession of up to 28 grams of marijuana, allowed individuals to grow as many as six plants and established a regulatory framework for the production and sale of cannabis products. Should the bill be signed into law in 2021, Mexico would become the fourth country in the world to legalise marijuana for recreational use. However, the drug’s importance as a source of financing to DTOs has been vastly curtailed in recent years due to the shift towards synthetic drugs and reduced demand from the US.

Prospects for peace

The persistence of widespread poverty and lack of economic opportunities for large segments of the Mexican population, combined with the inability of successive governments to establish a security policy that demonstrably reduces violence, suggests that the conflict against DTOs will not end any time soon. At best, the consolidation of a few large DTOs (namely the Sinaloa Cartel and the CJNG) could reduce competition between them and thereby reduce violence. The impact of government efforts at combatting financial crime and synthetic drugs on DTO finances could either reduce their capacity for violence, or alternatively lead them to expand their reach into other criminal, or even some non-criminal, activity.

Strategic implications and global influences

Cooperation with the US on security matters will remain an important pillar of the strategic relationship between the two countries. Despite the Biden administration’s focus on domestic issues in early 2021, migration was one aspect given immediate priority due to surging numbers of Central American migrants in the first months of the year. While Mexico largely cooperated with the Trump administration on migration, it will be tempted to assume a more assertive stance with Biden if it perceives that major disagreements can be avoided, such as occurred in mid-2019 and resulted in the threat of a trade war. This assertiveness could also further complicate cooperation on security matters, already strained by Cienfuegos’s arrest and Mexico’s reform of the National Security Law, which was ultimately watered down due to pressure. Mexico’s dependency on US intelligence and, to a lesser extent, resources, including for its weapons procurement, means that changes to existing cooperation arrangements are likely to be marginal, and little more than posturing.

Notes

- 1 Arturo Angel, ‘En México Asesinaron a Más de 35 Mil Personas en 2020, Solo un 0.4% Menos que un Año Antes’ [In Mexico, More than 35 Thousand People Were Murdered in 2020, Only 0.4% Less than a Year Before], Animal Politico, 21 January 2021; and Government of Mexico, Secretariat of Security and Civilian Protection, ‘Cifras de Delitos y Víctimas por Cada 100 Mil Habitants 2015–2021’ [Crime and Victim Figures per 100 Thousand Inhabitants 2015–2021], 20 June 2021.

- 2 Government of Mexico, Ministry of Finance, ‘Informes sobre la Situación Económica, las Finanzas Públicas y la Deuda Pública’ [Report on the Economic Situation, Public Finance and Public Debt], Fourth Trimestre, 2020, p. 38.

- 3 Ilse Becerril, ‘El Cártel de Santa Rosa de Lima Tras la Captura del Marro: Pactó con el CJNG y Ahora Opera con Solo el 60% de Sus Sicarios’ [The Santa Rosa de Lima Cartel After the Capture of Marro: It Made a Pact with the CJNG and Now Operates with Only 60% of Its Hitmen], infobae, 9 September 2020.

- 4 Transparency International, ‘Corruption Perceptions Index’, 2020.

- 5 Justice in Mexico, ‘Organized Crime and Violence in Mexico 2020 Special Report’, 30 July 2020.

- 6 Coneval, ‘Medición de la Pobreza – Pobreza en México: Resultados de Pobreza en México 2018 a Nivel Nacional y Por Entidades Federativas’ [Measurement of Poverty – Poverty in Mexico: Results of Poverty in Mexico 2018 at the National Level and by Federal Entities], 2018.

- 7 Inegi, ‘Principales Resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo (nueva edición) (ENOEN) de Diciembre de 2020’ [Main Results of the National Survey on Occupation and Employment (new edition) (ENOEN) December 2020], December 2020.

- 8 ‘Menores en la Delincuencia Organizada de México: a los 14 años Roban, Secuestran y Venden Droga’ [Minors in Organised Crime in Mexico: At Age 14 They Steal, Kidnap and Sell Drugs], Forbes, 24 September 2020.

- 9 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, ‘World Drug Report 2021, Chapter 3: Drug Market Trends: Cannabis, Opioids’, June 2021, p. 88.

- 10 Mexican Government, ‘Informe Anual de Seguridad 2020’ [Annual Security Report 2020].

- 11 Government of Mexico, Secretariat of Security and Civilian Protection, ‘Cifras de Delitos y Víctimas por Cada 100 Mil Habitants 2015–2021’ [Crime and Victim Figures per 100 Thousand Inhabitants 2015–2021], 20 June 2021.

- 12 ‘Ejército y Guardia Nacional, a la par con quejas en CNDH’ [Army and National Guard, On Par with Complaints to CNDH], El Universal, 8 February 2021.

- 13 Duncan Tucker, ‘La Nueva Guardia Nacional de México Está Rompiendo Su Juramento de Respetar Los Derechos Humanos’ [Mexico’s New National Guard Is Breaking Its Oath to Respect Human Rights], Amnesty International, 8 November 2020.

- 14 ‘The Devastating Toll of “Remain in Mexico” One Year Later’, Doctors Without Borders, 29 January 2020.

- 15 Institute for Economics & Peace, ‘Mexico Peace Index 2020: Identifying and Measuring the Factors that Drive Peace’, April 2020, p. 48.

- 16 ‘Informe 2020 del Gabinete de Seguridad. Conferencia Presidente AMLO’ [2020 Security Cabinet Report. President AMLO Conference], Andrés Manuel López Obrador, YouTube, 31 December 2020.

COLOMBIA

Sources: IISS; Colombia, Institute of Studies for Development and Peace (Indepaz); Verdad Abierta; El Espectador

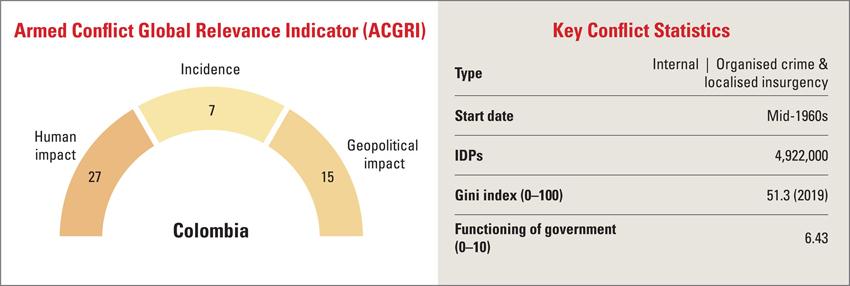

Overview

Colombia has been ravaged by violence since it became a republic in 1810. A low-intensity civil war between political parties in the 1950s (La Violencia) evolved in the 1960s to include multiple Marxist guerrillas fighting the state. In response to these guerrillas, paramilitary groups emerged in the 1980s, supported by state authorities and private actors. Since the early 2000s, the conflict has moved away from political goals and increasingly towards economic incentives, especially as drug trafficking became the most important funding source for illicit groups, both fuelling violence and making it more protracted.

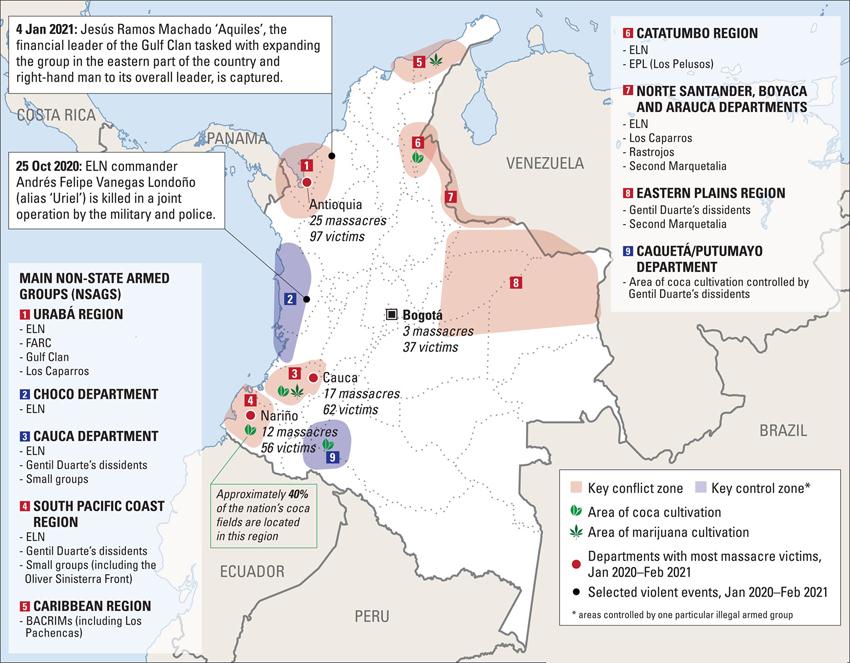

Illegal economies boosted insurgent and paramilitary capabilities amid a slow and weak state response, which resulted in the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrilla group controlling 40% of Colombia’s territory by 2000.1 A stronger reaction by successive governments – along with support from the United States under Plan Colombia2 – facilitated negotiation processes with FARC and the United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC) paramilitary group. By 2006, most paramilitary combatants had demobilised and in 2016 FARC signed a peace agreement with the government and began transitioning into a political party.3 Yet deficiencies in the implementation of the demobilisation and reintegration of combatants from both the AUC and FARC contributed to the emergence of bandas criminales or BACRIMs (criminal gangs) and FARC dissident divisions. These groups, along with the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), also known as the Pelusos, have reshaped the armed conflict in recent years.

In 2020, the ELN remained the non-state armed group (NSAG) with the strongest territorial presence and most significant military capabilities. However, FARC dissident groups grew and became better organised, with a single commander, Miguel Botache Santillana, also known as ‘Gentil Duarte’, bringing together six FARC dissident fronts in over half the country.

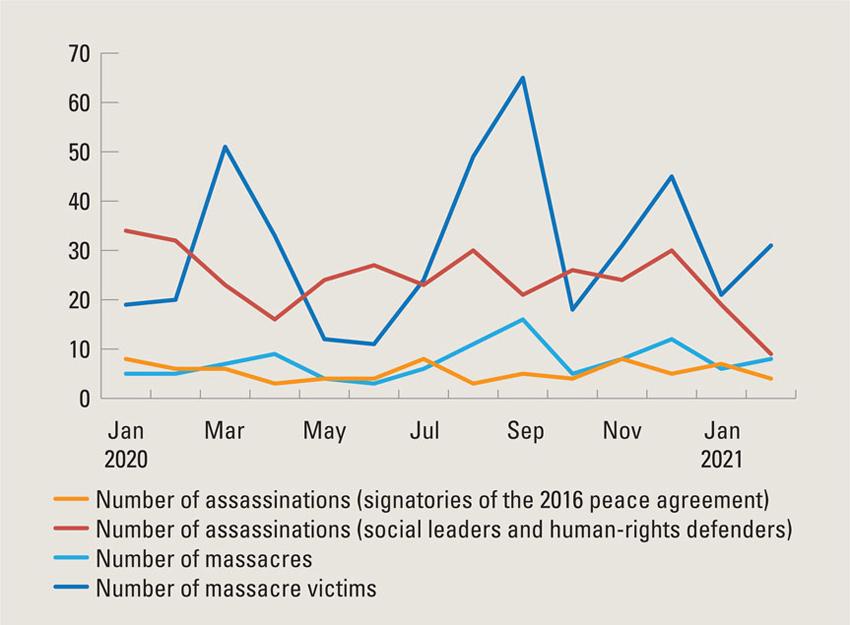

Competition over former FARC-controlled areas, coca cultivation, cocaine production and distribution corridors, illegal mining and extortion continued to underpin ongoing dynamics of violence. In 2020, 91 massacres were registered, a steep escalation from the eight registered in 2015.4 In 2020, the police registered a total of 368 terrorist attacks, representing a dramatic 98% and 204% increase compared to 2019 and 2018 levels respectively.5 Between October 2019 and September 2020, there were 193 direct confrontations between NSAGs and the Colombian armed forces, and 61 confrontations solely between NSAGs.6

Conflict Parties

Colombian armed forces

Strength: 293,200 across the army, air force and navy. The national police has 189,000 police officers.

Areas of operation: Across the country but limited presence in some rural areas such as the Catatumbo, Urabá and Pacific coast regions.

Leadership: President Iván Duque (commander-in-chief); Diego Molano (minister of defence); Luis Fernando Navarro Jiménez (general commander).

Structure: Army, navy and air force. The National Police (PONAL) is in charge of public and civil security. Though not formally part of the military forces, PONAL has been controlled and administered by the Ministry of National Defence and has had a militarised structure since 1953.

History: Originated in the late 18th century as the Liberating Army of the independence movement against the Spanish Empire. The military forces were formally created with the 1821 Cúcuta Constitution.

Objectives: Defend national sovereignty, consolidate the state against NSAGs and maintain rule and order.

Opponents: ELN, FARC dissidents, BACRIMs including the Gulf Clan, EPL and other criminal organisations.

Affiliates/allies: National Police.

Resources/capabilities: 2020 defence budget of US$9.69 billion and US$10.69bn for 2021. Overall capabilities have improved in recent decades. The army is planning to modernise its armoured fighting vehicles, while the navy has improved its offshore-patrol capacities in recent years. The ground-attack capabilities of the air force remain limited.

Gentil Duarte's FARC dissidents

Strength: Approximately 3,000 members.7

Areas of operation: Presence in at least 12 of Colombia’s 32 departments, mainly in Antioquia, Caquetá, Cauca, Guaviare, Meta, Nariño, Putumayo and Vaupes.8

Leadership: Miguel Botache Santillana, alias ‘Gentil Duarte’ (commander). 1st and 7th Fronts: Néstor Gregorio Vera Fernández, alias ‘Iván Mordisco’; 33rd Front: Jhon Milicias; Western Coordinating Command: Gerson Antonio Pérez Delgado, alias ‘Caín’, and Euclides España Caicedo, alias ‘Jonier’.

Structure: Replicates the former FARC operational structure with ‘fronts’ for each region. However, it did not retain FARC’s hierarchal system across regional groups. The fronts therefore enjoy greater freedom to make decisions and manage their finances at the local level.

History: The group brought together multiple FARC units that rejected the 2016 peace agreement. Most remained in hiding until 2018–19, before beginning to conduct activities while claiming to be the ‘true’ FARC.

Objectives: Overthrow the government and establish a socialist state.

Opponents: Colombian armed forces, the Gulf Clan, the Second Marquetalia and other smaller local criminal groups such the EPL.

Affiliates/allies: ELN Western War Front in the Chocó region. Mexican drug-trafficking organisations (DTOs), mainly the Sinaloa Cartel and the Cartel Jalisco New Generation (CJNG).

Resources/capabilities: Inherited FARC’s former economic structures and rent-seeking activities (including extortion, kidnapping, ransom and illegal mining). Drug trafficking or tax collection on drug distribution in its areas of influence. Possesses long- and short-range weapons, obtained from conflict zones in Central America, former Soviet bloc countries and illegal suppliers in the US.

Second Marquetalia (FARC dissidents)

Strength: Between 300 and 800 members.9

Areas of operation: Border areas with Venezuela, mainly in the departments of Guainía, Norte de Santander and Vichada, and others such as Antioquia, Cauca and Casanare.

Leadership: The main commanders include Luciano Marín Arango, alias ‘Iván Márquez’; Hernán Darío Velásquez, alias ‘El Paisa’; Seuxis Pausias Hernández Solarte, alias ‘Jesús Santrich’ (killed in May 2021); Henry Castellanos Garzón, alias ‘Romaña’; and Olivio Iván Merchán Gómez, alias ‘Loco Iván’ (killed in combat in November 2020).

Structure: Sought to incorporate other groups under the unified coordination of its four main commanders. Its organisational structure remains unknown, but it likely replicates the old FARC structure.

History: Created in 2019 when a group of senior FARC commanders – who were signatories of the 2016 peace agreement – abandoned the reincorporation process and resumed fighting.

Objectives: Overthrow the government and create a socialist state. Recreate the original FARC.

Opponents: Colombian armed forces, Gentil Duarte’s dissidents and the Gulf Clan.

Affiliates/allies: Non-aggression pact in Casanare with the ELN Eastern War Front and alliances with ELN fronts in Antioquia and Cauca. Allied with Los Caparros in Bajo Cauca where the Gulf Clan is present.

Resources/capabilities: Its sources of financing include former undeclared assets of FARC, the illegal transport of migrants, drug trafficking and smuggling. Renewed weaponry with more modern rifles such as the IWI Tavor X95.

National Liberation Army (ELN)

Strength: Approximately 4,000 members.10

Areas of operation: Operates in at least 16 of Colombia’s 32 departments and capital cities, including Bogotá.11 Retains a particularly strong presence along the border with Venezuela, especially in the departments of Arauca, Norte de Santander and Vichada, but also in the departments of Cauca, Chocó, Nariño and Valle del Cauca – where it has inherited FARC territories. Has also expanded rapidly in Venezuela.

Leadership: Nicolás Rodríguez Bautista, alias ‘Gabino’ (commander).

Structure: The Central Command (COCE) directs strategy and is composed of five commanders and divisions that operate independently. The ELN has seven war fronts, including the Camilo Torres Restrepo National Urban War Front which has a presence in multiple capital cities. Maintains a horizontal military structure with a high level of independence given to each front. Many FARC dissidents have joined the ELN in recent years.

History: Founded in 1964 by a group of Catholic priests, leftwing intellectuals and students embracing liberation theology and trying to emulate the 1959 Cuban Revolution.

Objectives: Overthrow the Colombian government and create a socialist state.

Opponents: Colombian armed forces, the EPL in the Catatumbo region and the Gulf Clan in Arauca, Antioquia and Chocó.

Affiliates/allies: The Second Marquetalia and other FARC dissidents in regions such as Chocó and Catatumbo; Los Caparros in Antioquia.

Resources/capabilities: Extortion, illegal mining and gasoline black market. Controls the illegal trafficking of timber and cocaine in various departments. Weapons come mainly from illegal foreign trade, including remnants of Soviet arms.

The Gulf Clan (also known as Gaitanistas Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AGC) or The Urabeños)

Strength: Approximately 3,000 members, though estimates vary.12

Areas of operation: Presence in at least 17 departments in Colombia, as well as abroad.13 Based in the Gulf of Urabá (on the Atlantic coast, close to Panama). Also has an extensive presence in the city of Medellín and departments such as Antioquia, La Guajira, Norte de Santander, Santander and Valle del Cauca.

Leadership: Dario Antonio Úsuga David, alias ‘Otoniel’.

Structure: About a third of the local cells are directly commanded by the leadership in Urabá, while the others are loosely affiliated with local criminal organisations, who use the name Gulf Clan and are expected to provide services or follow strategic orders when requested.

History: Emerged from the demobilisation of AUC paramilitaries in 2006. Some of its leaders and members are former EPL combatants and drug traffickers from groups that have since disbanded, such as the Popular Revolutionary Anti-Terrorist Army of Colombia (ERPAC).

Objectives: Drug trafficking. Using the name Gaitanistas Self-Defence Forces is a way of legitimising itself as a counterinsurgent group.

Opponents: Colombian armed forces, ELN, the Caparros, the EPL, Gentil Duarte’s dissidents and the Second Marquetalia (except in Córdoba and Antioquia).

Affiliates/allies: Works with the Second Marquetalia in Córdoba and Antioquia.

Resources/capabilities: Financing comes from transnational drug trafficking, providing services for independent drug traffickers. Multiple group members, including leaders, run their own international trafficking routes. Also involved in illegal prostitution, human trafficking to Panama and extortion.

Los Caparros

Strength: 400 members.14

Areas of operation: Lower Cauca area of Antioquia. After the peace agreement, they extended their influence in places such as Briceño, El Bagre, Nechí, Valdivia, Yarumales, Valdivia in Antioquia and Puerto Libertador and San José de Uré in Córdoba.

Leadership: Robinson Gil Tapias, alias ‘Flechas’.

Structure: Divided into three fronts: the Elmer Ordoñez Beltrán Front, the Carlos Mario Tabares Front and the Norberto Olivares Front.

History: Emerged from the demobilisation of the AUC in 2006 as one of the groups from the Gulf Clan. With the FARC demobilisation and the assassination of Danilo Chiquito, one of the main leaders decided to start his own group.

Objectives: Control drug trafficking in Córdoba, Antioquia, especially in the mountain range of the Paramillo Massif.

Opponents: The Gulf Clan and the Colombian armed forces.

Affiliates/allies: The Second Marquetalia and the ELN, in Córdoba, Sucre and the Urabá Gulf.

Resources/capabilities: Involved in all stages of drug trafficking (coca cultivation, cocaine production and international shipment) in the departments of Córdoba and Antioquia. Also engaged in illegal mining.

Conflict Drivers

Political

Slow implementation of the peace agreement:

President Iván Duque was elected in 2018 on a platform of scepticism around the 2016 peace agreement. While his government allocated around US$684 million for the Development Programmes with a Territorial Approach (PDETs), multiple voices have denounced the slow pace and low political will to produce tangible results.15 For example, the construction of public works stipulated as part of the agreement has slowed down dramatically: whereas 544 construction projects began in 2019, only 53 started in 2020. Moreover, 38% of the required legal adjustments for implementation were still pending.16 As a result, NSAGs have reoccupied many areas of the country, with their presence reported in 30 out of 32 departments.17 Meanwhile, demobilised FARC combatants faced increased insecurity, with homicides increasing sharply from 32 in 2017 to 73 in 2020.18

Economic and social

Socio-economic inequalities and institutional flaws:

Widespread inequalities, in land ownership and other areas, have historically fuelled the conflict. Colombia is Latin America’s second-most unequal country, with a 27%19 monetary poverty rate and a Gini index of 51.3.20 This inequality is exacerbated by the state’s inability to provide justice and resolve land disputes, as well as widespread corruption. Colombia also consistently ranks in the lower half of Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.21

Illegal economies and coca eradication:

Coca crops and cocaine production remain important drivers of violence, as the most important revenue source for illicit criminal and terrorist groups, as well as an income source for marginalised rural communities. The latter’s relationship with national authorities is therefore strained by efforts to forcefully reduce cultivation. Legal restrictions on aerial fumigations enforced by the Constitutional Court since 2017 have undermined government eradication efforts, necessitating the use of manual methods instead, making the process longer and more labour-intensive.

International

Venezuela:

Venezuela continues to play a significant role in the Colombian armed conflict, acting as a safe haven for Colombian NSAGs such as the ELN and some FARC dissidents. As of May 2019, around 50% of ELN members were thought to have taken refuge in Venezuela.22 Ongoing socio-economic and political turmoil in Venezuela has also triggered a major regional migration crisis, causing approximately 5m people to flee, with most settling in neighbouring countries, including 1.8m in Colombia.23 Over 50% of these migrants were deemed to have an irregular status,24 and almost 30% settled in neighbouring departments such as Norte de Santander and La Guajira, areas with a strong military presence of diverse illegal armed groups.25 This migrant crisis has further stretched the Colombian government’s limited capacity to address diverse pressing economic and social problems in the country.

Political and Military Developments

JEP moves forward

Despite the controversy surrounding the Special Justice for the Peace (JEP) created by the peace agreement, the tribunal continued its investigations into the seven macro cases that have been opened. More than 300,000 victims have registered under the JEP and over 12,000 individuals have submitted themselves to its jurisdiction, including 9,806 former FARC combatants and 3,007 members of the military and police.26