10 Income From Recording

Until the 1950s, recording artists were not paid royalties for the sale of recordings. They were paid in a similar manner to session musicians, meaning they were paid at the prevailing rate for a vocalist who sang at a recording session, and that was the end of the compensation. Those artists who negotiated for a royalty for recording music “only received a penny amount per sale rather than a percentage of a sales price as they do today.” (Butler, 2004) For the artist who owns their own label and markets their own recordings, income and earnings from their sale is immediate. In most instances, however, aggregate earnings from them will be far lower than for those artists who are signed to recording contracts with bigger independent or major labels.

The artist manager’s relationship with the record label will depend on the size of the artist’s earnings. For managers with top sellers at major labels, they will be like staff members of the label. However, do not be surprised to find that, as a manager of a mid-level or developing act, that the attitude seems to be one of tolerating the fact that the artist has a manager with whom the label staffers must deal. Our discussion of income from recordings will begin with a look at what a contract with a large independent or major label can mean to an artist and their career.

Recording for large labels

From the artist manager’s perspective, the record label represents an important career-marketing machine for the artist as well as an indirect income generator for other aspects of the artist’s career, both as a writer and performer. So the recording contract can play a pivotal role in career development. Knowing that this will require the formality of a contract, the manager should seek an experienced and active entertainment attorney to handle the negotiations with the label. Entertainment law is a specialized area with new contract provisions occurring as regularly as the music business changes— almost daily. An experienced attorney knows what he or she can get as concessions from the company and they also know what contract provisions might be open for negotiation for a better deal for the artist. The manager should let the attorney be the negotiator, but he or she should be at all meetings where negotiations are taking place. Since business negotiations can become contentious, it is better for the attorney to take the hard-line role with the label rather than the manager, since the manager will be conducting business with the label when the contract has been completed.

When you cut away all of the fine print of any contract, it is simply an exchange of promises. With a recording contract, the basic promises exchanged are these: the artist promises to create recordings exclusively for the record company, and the company promises to commercially exploit the recordings. Labels essentially promote and market recordings, and the recording promoted by the label results in immense benefit to the other aspects of the artist’s career. Among the most valued contributions a label makes to an artist’s career is when they actively promote the recording for radio airplay resulting in a greatly increased connection of the artist’s music to active consumers. The label often creates a video to accompany the release of the recording, which is then promoted to national and international music video channels, and to local video programs adding extremely valuable visual promotion of the artist and their music. It is impossible for managers of new artists to find this level of funding to promote an artist, and this is why the label becomes so important. The immediate benefits to the artist include quickly increasing their public profile and exponentially building a fan base that purchases tickets to performances. Clearly the release of a recording promoted by a record company can infuse considerable energy into a career. As we will see in the next section, the actual earnings for the artist from a recording can be a complicated, slow-to-arrive income source, especially for the new artist.

Income and expenses for the artist from a recording contract

A recording contract specifies how the artist will earn income from the relationship with the record company. The contract will say that the record label provides all financing necessary to create the recording. But it also includes specifics about what the artist must recoup to the record label as part of their standard agreement to pay for the creation of their own recordings. As you read this section, keep in mind that the expenses being charged to the artist are payable to or recoupable by the record label only if the recording earns adequate income from the project to pay them. The artist will not be personally liable for repayment for any losses as a result of the creation and marketing of the recording. If it does not make money the artist must repay nothing. The understanding that the label is taking the financial risk for the recording project helps to explain why the label has considerable control over how the recording is handled as a commercial music project.

One notable exception to the artist repaying recoupable expenses occurs when they are offered a second album after the first one loses money for the record label. In this instance, losses from the first album will be carried forward to cross collateralize the second album. This means that the artist will not be paid royalties until the recoupable items from both albums have been repaid through the artist’s royalty earnings.

Creating and paying for the recording

The contract with the record company will require that the artist pays for all of the costs of recording an album. Remember, the artist has agreed to create recordings and the label expects them to pay for them as part of that promise. All of the recording costs including the studio time, payments to players on the recording session, payment to the producer of the recording, travel costs, instrument cartage, and dozens of other expenses are all borne by the artist. This does not mean the artist pays for the recording from personal funds; rather, the record company will actually pay for the recording as a form of an advance to the artist, and its expense will be deducted from the album royalties that the artist ultimately accrues as the album is sold. When this and all other recoupable expense deductions by the record company have been made, royalty checks will begin to issue to the artist. We will discuss other deductions against royalty payments later in this chapter.

As the manager begins preparation to negotiate the recording contract with an attorney, it is important to know that advances to the artist are specifically noted in the original contract with the record label by amounts and in association with which albums.

The artist will also be offered an advance as an incentive to sign the record contract and to help offset living costs while the album is being created. The label may agree to issue a check for $50,000 as an advance, but the manager and artist must remember this is merely a loan against the future anticipated royalties the artist will earn from the sale of the recording. So if the recording session costs $250,000, and the advance is added to that amount, the artist has created a $300,000 obligation against the future earnings from the recording.

For several reasons, it is always advisable for the artist manager to negotiate as large an advance as possible from the record label. First, an advance is the ideal income source to help pay off existing debt the artist has accrued and to help the manager put together a new show for the artist to take on tour. Second, because of the way record companies handle their accounting and payments to a new artist, it might be two or three years before the artist is issued their first royalty check from sales of the recording. A large, early advance puts income into their career now and not later, and given the odds against the recording project ever breaking even, there is a good possibility that the advance may be the only money the artist ever receives from the record label. Finally, advance checks from record companies are immediately commissionable to the artist manager because they are actually pre-payment of the artist’s future earnings. For the manager of a new artist, this commission will help offset considerable personal expense that has accrued launching the career of the artist. Some would argue that large advances might make the artist unaffordable to the record company, but labels are conservative by nature and will advance only amounts that they feel they will recoup.

Artist’s income

An artist earns most of their income from the record company in the form of royalties that are due, according to the recording contract, each time a copy of the recording is sold at retail. Royalties very simply are a percentage of the price of a recording paid to the artist, operating very much like a salesman’s commission.

The “price” against which the artist’s royalty payments are made is defined a couple of ways. Many new recording contracts specify that the royalties paid to an artist are a percentage of the wholesale price of the recording, meaning they are paid a percentage of the price that the record company charges its dealers who distribute their recordings. Simplifying the math, if an artist is paid a 10% royalty for each recording sold and the wholesale price is $10, then the artist earns one dollar in royalties per recording sold. Another way royalty payments are determined is found in many older contracts—and some new ones—that still contains language saying that royalties are paid as a percentage of the suggested retail price minus a 25% charge for packaging. There are actually more calculations to determine royalty earnings, but this shows the basic concept of payment by the label to the artist.

Royalty rates for new artists can range from 12% to 14% for each recording sold; more established artists can earn up to 20%, and major recording artists might exceed 20%. (Hull, 2004) Most contracts also include a provision that allows the royalty rate to increase as a recording reaches sales plateaus such as a half million or million units.

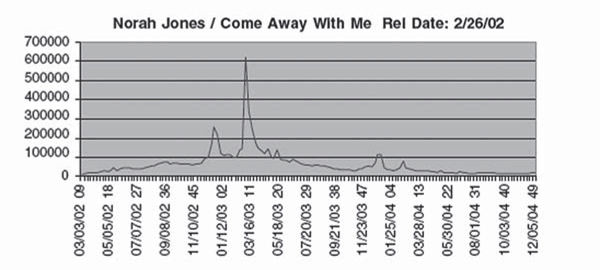

Royalty payments for new and established artists flow very differently, primarily because of the artist’s relative positions in their careers. The new artist has a growing base of fans that is slowly becoming familiar with the artist and is beginning to buy their music as shown in Figure 10.1. This is a view of the product life cycle for the first album for Norah Jones. (Hutchison, p. 114) You can see that initial sales are slow to build, but eventually the artist’s music begins to sell very well where you see the spike. Like all products with a limited shelf life, the album sales begin to slow after it has been in the marketplace for a while, and the label then prepares for the second album release. Toward the left of the chart, sales are slow, album development expenses are high, promotional expenses are very heavy, and there is income but little earnings for the label and the artist—meaning that artist royalties may be nonexistent.

Figure 10.1 The product life cycle for the first album for Norah Jones

(Hutchison, 114)

Throughout the life of the recording, the label is also collecting royalty earnings for the artist based on the shipment of the recordings into the marketplace. As the shipments are made, the label sets aside the artist’s royalties for each and holds them in a reserve account. As the royalties accrue to the artist, costs that are recoupable to the record company are paid from that account. This simply means that the label applies earned royalties to the money the artist owes back to the label for creating the recording. As you can see from the chart, sales grow slowly for many new artists. For the artist used in this example with a $10 wholesale price, a 7% net royalty (we subtracted the producer’s 5% from the 12% all-in rate) means the artist earns 70 cents for each album sold. Based on that math, the artist will be required to sell over 500,000 copies of the album before the $350,000 recording fund (recording session plus advance) has been recouped by the label. And there are many other charges back to the artist that require recoupment before royalty payments are paid to the artist. It becomes easy to see why artists may not receive a royalty check from the label for perhaps two years after the first recording was released, if ever.

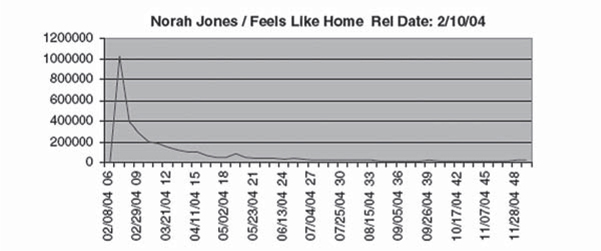

For the established artist the life cycle of a recording looks like the graph in Figure 10.2. (Hutchison, p. 114) Consumers had become very familiar with Norah Jones’ music and they reacted quickly in acquiring her second album. As shown in the chart, sales typically spike within the first 90 days of release, and then have smaller spikes throughout the life of the recording as singles are released. In this instance, income arrives quickly to the label, costs are recaptured quickly, and the label is able to distribute royalties much earlier than for the first album released.

Figure 10.2 The product life cycle for Norah Jones as an established artist

(Hutchison, p. 114)

The timing of royalty income is important to the artist manager since one of the typical responsibilities they have is to manage a budget for the artist. Labels distribute royalty checks for recordings three quarters (one quarter equals three months) following the release of the recording. Remember that the artist must recoup certain recording and other expenses to the label before they are entitled to royalty payments, so the timing of their earnings may take considerably longer than nine months to appear. The label may be able to give the manager an estimate of when and how much the royalties will be when they are distributed.

New and established artists must deal with another delay of royalty distribution, which is defined by label accountants as “the reserve for returns.” The artist’s royalty account is based on shipments of recordings minus the royalty value of the albums that are returned unsold. In an effort to hedge the overpayment of royalties to artists, the label withholds 20% of royalties that are due to the artist in a separate account that is referred to as the reserve account for returns. When the album has completed its life cycle, distributors return the unsold recordings to the label. The label then deducts the value of artist royalties for the returned recordings from the reserve account for returns, and then pays the balance (if there is one) to the artist. (Macy, 2006)

How does an artist manager determine if the royalty payments to the artist are accurate? Most recording contracts allow the artist a two-year window within which to request an audit to confirm that payments are accurate. However, a recent California law has extended that to three years, and it has given more latitude on the choice of the auditor who is permitted to examine the label’s accounting records.

As a footnote to this section discussing an artist’s income from a recording, it is interesting to also look at a major label’s income sources from hit recordings. Warner Bros. gave the New York Times a candid look at the 2006 earnings of one of their hip-hop releases, which showed:

• The physical CD was responsible for generating 74% of the income for the project, or $17,000,000 dollars.

• The sale of various digital products associated with the artist and the CD increased the earnings by $6,000,000 dollars, with $4,000,000 of that generated by ring tones edited from hit singles.

• The digital earnings figure also included over $300,000 for mobile games played on cell phones and an additional $94,000 spent by consumers to purchase wallpaper for digital devices. (Leeds, 2006)

It is clear that earnings directly associated with recordings will continue to evolve.

The role of the producer

Another element that impacts the earnings of the artist is the cost of paying a producer to create the recording. The producer is the individual who assembles all of the necessary elements to take into the recording studio to create the recording. This ranges from reserving a studio, to finding musicians, to helping choose songs for the artist to record. Since the artist pays for the recording, the responsibility of paying the producer is the artist’s, and this is done through the artist’s royalty earnings.

Also, an artist signed to a record label with an “ all-in” contract means that the specific royalty rate being paid to the artist includes the royalty payment to the producer of the recording. For example, the artist who earns a 12% royalty may be required to pay 4% or 5% of that royalty rate to the producer, reducing the artist’s earnings to 7% or 8%. Many producers require an advance paid by the record company followed by earnings from royalties. Because the record label is fronting the money to create the recording, their position is that of a key stakeholder in its success, so the company will have considerable input into who is chosen to produce the recording. The artist and producer certainly must have compatible creative chemistry, but the label will want to have the right to overrule a decision by a new artist on who the producer will be.

The choice of the producer will be based on who can create commercial music using the talents of the artist that will result in a recording that will connect with music consumers. The label and the artist will look for a producer who has a good or a developing reputation, and one who is a good creative “fit” with the artist. Labels also seek producers who have their own marquee value to radio programmers as well as with the consumer. The success a producer has with other artists builds a reputation can help market the music of a new artist.

Other expenses charged to the artist

The label has promised to market and exploit the recordings that the artist creates. However, the marketing they are willing to pay for has limits. When these limits are exceeded, the excess is charged back to the artist with their permission, and the artist must pay for it with royalties earned from the sale of the recording. Here are some of the charges the manager can expect to see on the artist’s statement of account.

• A portion of the video will be charged to the artist. Recording contracts often specify that the label will pay half of the cost of a video up to a total of $100,000; the artist will pay for all amounts that exceed that. Competitive country videos can be created for less than $100,000, but videos for BET and MTV2 can easily exceed $250,000 dollars.

• If independent radio promotion people are hired—those not directly employed by the record label—to attain radio airplay, the artist may be required to pay half or all of this additional expense.

• If independent publicists are hired (those not under contract with nor on the regular payroll of the record company), they will be paid entirely by the artist.

• If the record company pays for any aspect of live performances, the entire amount becomes recoupable. This would include costumes, hairdressers, makeup assistants, and other stylists—plus any transportation or equipment required for a performance.

• The artist will also be required to pay all costs of creating multimedia configurations of the recorded performance for current and future technologies.

• Any tour support money provided by the label will be recoupable by the label.

• An array of other things might be charged back to the artist. For example, if the artist wants an upgraded jewel case for their CD, they will be charged the difference; if the artist wants a full color jewel case booklet rather than one with black and white interior pages, they will be charged additional.

Any charges to the artist that are beyond the specifics in the recording contract will require the approval of the artist manager before the artist becomes obligated for the expense.

Deductions from the artist’s earnings will also include a reduced royalty rate for recordings that are sold at military installations and for those sold in foreign markets. Certain taxes are also deducted from the artist’s earnings.

Things for which the label customarily pays

The manager will find the contract contains some things that a record label typically provides as part of its agreement with the artist. Labels will pay for the manufacturing of the physical product after it is mixed and mastered.

Promotion costs are paid by the label. In this instance, label “promotion” is more like lobbying. Most labels employ promotion people whose responsibility is to influence radio programmers to choose the label’s recordings to be played on the radio. The personnel costs for this service are borne by the label. However, if outside independent promoters are hired, some or all of this additional cost will accrue to the artist. Label promotion also includes those at the label who are trying to influence programmers of video channels to choose the artist’s work, and those who are working with Internet websites to find opportunities to expose the artist’s music.

The label also pays for marketing costs, which includes advertising. The label makes advertising decisions based on the most effective way to place a paid message in front of a consumer within the target market of the artist. There is a wide array of media to carry the message, and the label will choose the most efficient way to use the available advertising budget to reach the consumer. Other marketing costs can include product design, wholesale and retail distribution, shipping, publicity, tour support, and a portion of the video production. Labels will view some of these as products of their creative services department, but they all serve to market the recording.

It becomes the responsibility of the artist manager to assure that their artist is getting the best opportunity for success with their recorded music project. A prominent record promotion executive with a major label said, “All artists are not created equally at a label,” meaning that artists have similar contracts with the label, but they can be treated quite differently in the way company resources are used to promote the artist’s recordings. A manager needs to have a good relationship with the promotion people at the label and needs to be actively and continually aware of the amount of effort the label is making to promote recordings—in part because the cash cows will always get what they need and the new artists will get what’s left. This becomes one of those times when the artist manager must be a very aggressive advocate for the artist to be sure the label gives the artist a reasonable amount of the resources needed to make the recording a success. It is logical to assume that labels would want to commit resources to make all of their recordings successful. However, many radio promotion people are paid based upon the chart position achieved by a recording, and/or retail sales of a recording, so they will put their energies where it has the most impact on their personal bonus structure.

Current trends in contracts for recording artists

Trends in recording artist contracts being offered by major labels and large independent labels contain numerous concessions that contracts have traditionally not included. Labels are seeking ways to reduce their financial risk and increase their earnings by linking to income streams that were previously reserved only for the artist. These new contracts are multiple rights agreements—sometimes referred to as “360 deals”—and will likely include the following additional provisions that will make the label a partner with the artist by sharing non-traditional income.

• The label will require ownership of the official website of the artist including the right to sell advertising and the artist’s merchandise on the site. And though the label will own the website, costs to create it will be charged back to the artist and will be recoupable. If the artist is able to share the income generated by the website the manager will be required to negotiate that as part of the recording contract.

• Income earned by the artist from touring and merchandise sales must be shared with the label. The amount of this percentage varies, depending on the label, and is an important negotiating point for the manager and the artist’s attorney.

• The newest contracts give the label a license to use artwork created for the album for other products.

• The creation of ring tones, voice tones, and ring backs for the label’s promotional use are contract requirements. The new artist will also be expected to agree to the use of their image as computer wallpaper. The promotional use does not necessarily need be linked to an artist’s album project, and because it is used for promotional purposes there will be no royalties paid.

• Labels seek to sell more music electronically and are interested in increasing the number of outlets that will sell the artist’s recordings. However, as the manager will find in the contract, revenue from electronic sales of recordings is significantly lower than for the standard CD. As the label sells more albums online, the overall units-sold royalty income to the artist will decline.

• Contracts being offered by labels continue to include a required deduction for packaging and they create a reserve for returns for sales of singles and albums online. Online sales have no packaging and music sold online is not returnable, but expect this provision to be included in the contract.

• When an artist’s recording is licensed for a use for something other than a sound recording, perhaps for use in performance DVD, the artist can expect to earn 12% of the net earnings produced by the license. Net earnings means the income after all expenses are paid. Previous contracts offered to artists set the net income sharing with the artist at 50%.

• The manager should also be alert to the number of recoupable expenses to the artist, and to watch for an increase in the percentages of recoupment to the label of things like the cost of a video. For example independent promotion costs had been shared equally with the label in the past, but labels now shift a greater percentage of that to the artist in the newest contracts.

(Milom, 2006)

As labels seek to find ways to improve their profitability, contracts offered to new artists will continue to include creative ways for labels to participate in the earnings of the artist. However, as artists and their manager’s track the value of new media developments, more income opportunities become available and they are now demanding more income for the use of their talents. For example, artists are seeking higher fees for licensing music videos in which they are featured. As Billboard notes, there are more online outlets that feature video as website content than ever before, and artists want to participate in the revenue that is generated. (Bruno, 2005) Google, Yahoo, YouTube, MySpace, AOL and others generate massive amounts of Internet traffic to their websites and record labels have found ways to profit from it, and artists seek their share.

The author extends an expression of gratitude to veteran entertainment attorney Mike Milom of Bass, Berry & Sims, PLC, and to Music Row publisher David Ross for permission to use the information in the previous section.

A changing model for major labels?

As labels seek ways to cope with the decreasing sale of recordings, a model likely to emerge is one in which new artists are signed to label contracts as “ brands,” and will become managed in all aspects of their careers by the label. Salaried brand managers will receive bonuses based on their successful commercial exploitation of all of the artist’s talents. Labels will pay for recordings, using them as both catalysts and foundations to generate all possible income streams for the label and the artist. Management functions don’t change. They instead become employed by the label with the title Brand Manager, with the label providing the investment necessary to launch the career as a brand. Visit this book’s website, www.artistmanagementonline.com, for more on this subject.

Artists who record for independent labels

Independent record labels often serve musical niches that the majors do not seek, but they can also give developing mainstream artists a place to prove their commercial viability before the manager presents them for a recording deal with a major label. When an artist demonstrates they have the ability to artistically connect with paying customers, the manager has a very strong position from which to negotiate a recording contract with a major label.

From a sales perspective, independent labels account for a quarter of the music recorded worldwide, and few independent labels have the resources that permit them to compete for consumers at the level of the major labels. Most do not. (Legrand, 2004) As a result, they approach their business very differently, and the artist manager approaches his or her profession on behalf of the independent artist in a different way too.

Unless they are very large companies, independent labels typically cannot afford a staff to promote a recording to radio. Nor can they afford advertising, videos, video promotion, and price and positioning at retail. They rarely have money for tour support. Compared to the 500,000 units sold for a moderately successful major label project, a successful recorded music project for an independent label sells in the range of 100,000 to 200,000 units. (Gordon, 2005) What does this mean to the artist manager?

It means the manager, by necessity, is very involved in the independent album project and is key to generating income from the sale of recordings. Much of the “ marketing” for an independent recording is coordination by the manager of the artist’s activities to promote the release of the project, and the resulting publicity and performance dates. Some independent labels help support the project with their staff publicists and with street teams and Web promotion. Most of the sales of recordings are the result of live performances with the sale occurring either at the venue or at local stores on days surrounding a performance. (Hutchison, 310) The growth and potential of online promotion and sale of independent music is explored in depth in Chapter 7 where we look at the manager’s work for the artist using the Internet.

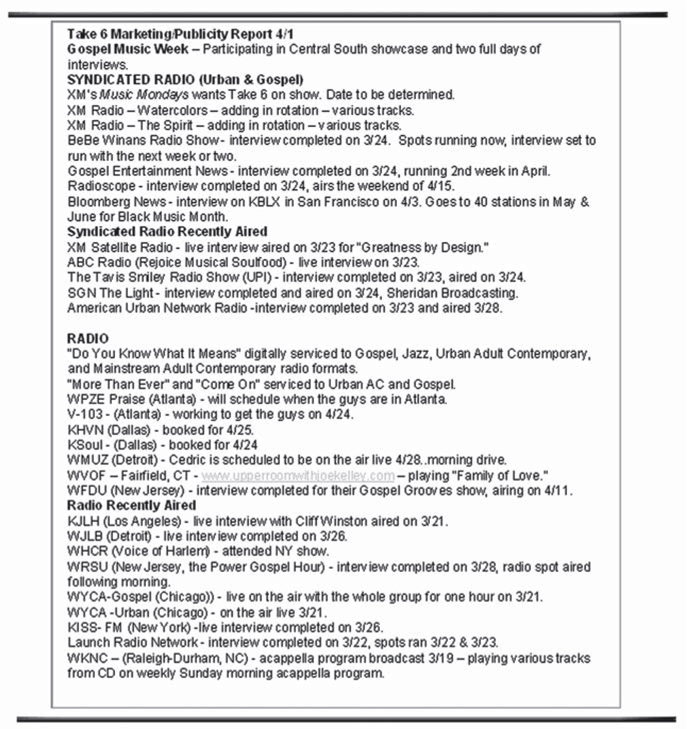

It is difficult to appreciate the amount of effort required by the artist manager on behalf of an artist releasing a recording on an independent label without looking at an example. To support a very active touring schedule, Grammy winners and platinum-selling artists Take 6 released an album in March 2006 on an independent label, which they own. Industry veteran and artist manager Chris Palmer had spent months planning for the release of the recording and created an immensely active schedule of public appearances and meetings with the media to promote it. He was managing in an environment that had a very limited budget, a small management staff of two (including himself), and a few contract team members for the Web and promotional support. Periodically he provided members of the artist’s team with updates of the activities he was coordinating in his “Marketing Report.” His April 1, 2006 report shows the enormous amount of planning and continuous follow-up and coordination necessary to execute a marketing plan for an independent label. An extract from his report is presented here with the full report reprinted with special permission from Chris Palmer as Appendix A. Major labels and large independents handle these activities on behalf of artists; for smaller independent labels, the work and responsibility falls to the artist manager.

Figure 10.3 An extract from the marketing report of Chris Palmer

It’s business

In all of the dealings that the artist manager will have with the record company it is important to remember that the label is in the business of selling recordings. The key word here is “business.” And when the artist is signed to a label, they become an asset as much as any other item of value listed in the company’s annual report. Assets are managed to the financial benefit of the company until they no longer have value. In the case of an artist, when their recordings are no longer selling they are no longer an asset, and the company ends the business relationship. The joy of the shiny new recording contract and promises of stardom—will eventually become a visit by a label representative from top management with the message that their business with your artist is over. Sometimes the label will deliver the news personally to the artist, but it often becomes the regrettable duty of the artist manager to be the messenger.

Through it all, always remember that this is business, and that selling recordings and associated products drive the bottom line for the record company.

The role of radio in the recording artist’s income

Many of the traditional forms of promoting the artist are relatively straight forward. For example, when an artist appears in a town for a live performance there is publicity through the media, music is played on radio, advertising is purchased, tickets are sold, the performance sells seats, and the artist sells recordings and merchandise as a result.

Some say that traditional radio exposure of an artist’s music is responsible for 70% of the sales of an artist’s recordings. While the role radio can play in the promotion of an artist’s career may seem obvious, the way radio uses that relationship is not so obvious. In this section we will look at traditional terrestrial radio, what the priorities are for radio and its owners, and how the artist manager can use this information for the benefit of the artist’s career.

The business of radio

It is important to understand what business radio is in, and what business it is not in. Radio is not in the business of selling recordings, promoting careers of artists, selling concert tickets, nor working to assure a healthy music business. With the exception of when a radio station promotes a concert and sells tickets, none of this activity surrounding an artist goes to the profitability of the radio station and is not important to its business other than for its promotional value. What is important to the radio station is its number of listeners. Veteran radio programmer Lee Logan once said that the business of radio is to build an audience to lease to advertisers. And that is as succinct as one can put it.

Let’s look at the first part of that statement. Radio builds audiences. The purpose of the entertainment you enjoy on radio is to attract your attention and keep you tuned in. Even though radio audience measurement company Arbitron continues to show that talk radio is the most popular radio format in the US, over 80% of the remaining radio stations program some form of music to entertain its audience. (Arbitron, 2006) In order to build a particular station’s audience, the programmer—who makes all decisions about everything that goes out over the air—seeks music and on-air talent that will keep its current audience and attract new listeners.

Now, to the second part of Lee Logan’s statement. Advertising rates are based exclusively on the number of people who listen to a radio station, so the larger the audience that the programmer can build, the more the station can charge for its advertising, and the more money the business will make. For example, in Los Angeles, Arbitron audience ratings for station KZLA continued to decline from 2.1% share of the city’s radio audience to a rating of 1.7% by the summer of 2006. The result was that the station replaced personnel and changed its format from country to a contemporary hit format. (Satzman, 2003) Why? They switched formats because a change of 1/10th of 1% of the audience share in Los Angeles is worth one million dollars of advertising revenue per year for the station owners. KZLA ownership felt they would draw a larger audience share with a different programming format. The same principle applies to commercial radio stations everywhere, though the financial impact depends upon the audience size of the radio market.

The point of this is for the artist manager to understand what is important to commercial radio. In order to get anything done through someone else, you must understand what they need. In the case of radio, they need growth in their audience share. As a result, programmers are very careful to play music that will keep current listeners and attract new ones, and they will program their stations to be predictable by meeting the listener’s expectations when they tune into the station. If the manager’s artist is too unlike the music being played on the station, this conservative nature of most programmers means they will not schedule the artist’s music for airplay.

Most music will never be heard by a commercial radio programmer or music director without aggressive one-on-one promotion by someone skilled and experienced in getting it done. If the artist is signed to a major label or a large independent, the company will have a staff that promotes recordings to radio. Programmers will know that there is a significant promotional effort behind a recording and it will be apparent that the artist’s recording is intended for mass commercial marketing. It is easier to get the consideration of a programmer under these circumstances than if the artist is new and is on an independent label with no affiliation with a major.

This is not to say that the new artist the manager just signed will never find their way to radio. A continuing classroom exercise by the author examines the Billboard Top 200 sales chart and finds that for most business quarters except the fourth, 20% to 30% of the artists who are in the listing of the top 50 selling albums are relatively new artists. Considering the number of veteran sellers of hit recordings who crowd the top of the sales and airplay charts, these observations show that there is opportunity for a new artist. We liberally define a new artist for this purpose as one who has been active with their first commercially viable single and album over the last year or 18 months.

The charts

There are two kinds of “charts” that the manager should understand. Billboard publishes its Top 200 each week, which is a ranking of the top selling album recordings in the US. The publication includes the weekly chart that ranks the position of the recording based on sales, but it does not show actual sales data. The sales data is proprietary information that is available only to those companies that subscribe to the data services of SoundScan. Each time a recording is sold in the US at a retail store or online, SoundScan captures the information and reports it to its central data assembly location. The 7 days of sales that make up the Top 200 charts end at midnight EST, and the sales data then is reported early Wednesday morning to SoundScan clients. Also, the Billboard magazine chart that is created for the publication shows the rankings 1–200 without the actual sales data. As a point of reference, there is no company anywhere other than SoundScan that compiles verifiable and actual sales data of recordings.

The other kind of chart the manager should understand is an airplay chart. Where the Top 200 shows the sales of albums, airplay charts show the number of times a single has been played on commercial radio. A number one song is the single that receives the highest amount of radio airplay for a 7 day period. (A number one album is the one that sells the most within a 7 day period.) Billboard magazine publishes airplay charts each week in its magazine, which is a guide showing how often songs are being played. Similar airplay information is compiled by another company called MediaBase, which is published each Tuesday in USA Today, and through other publications and websites.

Airplay charts are convenient guides to radio programmers so they will know what songs their counterparts in other cities are choosing to play most often. Radio programmers have wide and varied duties at the radio station and making decisions about which music to play and which music to stop playing is just a part of their responsibilities. To the programmer, the airplay chart is used as a reference, or barometer, of how songs are performing elsewhere. The research, experience, and understanding a programmer has of the local radio market are perhaps the most important criteria in the music selection decisions.

College radio

College radio in recent years has picked up considerable competition from the Internet as a source for filtering new and interesting music. However, it still has enough reach and impact that the manager of an artist should not overlook its influence. In the 1980s, college radio was the source for music that was overlooked by commercial radio because it was generally viewed as being out of the mainstream. The alternative music format began at college radio and now has its own commercial format following. (Calderone, 2005) Because college radio is noncommercial, it has limited resources to market and promote itself. The traditional programming of college radio is to offer small blocks of time during a broadcast day to introduce audiences to a broad array of music that defines the adjective “eclectic.”

The size of college radio audiences is often much smaller than the commercial counterpart. In a mid-size southeastern US city, the suburban university’s college radio station has 2,000 unique listeners each week. Its competition at a nearby urban university has a weekly audience that is nearly ten times as large. By commercial radio standards this is still a relatively small listener base, but it can be an important promotional avenue for the artist building a fan base and who is on tour playing at venues appealing to college students.

Sponsorships, endorsements, television, motion pictures

Among the things that an active and visible recording career can provide is access to other ways to earn income and to exploit the talents of the artist. Sponsorships and endorsements are offered to an artist when the target market of a brand are the same as the artists’, or the target market of the artist is one that the brand seeks to have as its customer. The manager and sometimes the agent will be able to negotiate a sponsorship on behalf of the artist.

Carolyn Ballen from The Indie Music Forum offers some ideas that can be presented to a possible sponsor about the benefits that sponsoring an artist could be. They include:

• An endorsement from the artist in the sponsor’s advertising.

• The sponsor has access to a large following of people within the sponsor’s target market.

• A logo presence via a banner or product demonstrations on the grounds of performances.

• An ad in the artist’s CD.

• Mentions about the product from the stage.

• A logo on all printed materials, including advertising, and logos with links on the artist’s website.

• Promotion of the brand in all fan club emails and other consumer communications.

(Ballen, 2007) Starpolish.com.

There may be a temptation by an artist-songwriter to include a sponsor mention in their song lyrics, but radio programmers are sensitive to the use of this Trojan Horse-style of commercial promotion and will likely not program the song.

Sponsorships can amount to a few thousand dollars for a local or regional touring band, but easily goes into the millions for major artists.

Television and motion pictures can add an additional dimension to the career and income of an artist, and this is often done with the help of a full service booking agency such as Creative Artists Agency or the William Morris Agency. These organizations have the in-house resources to represent the artist in both their music as well as for any acting opportunities that may be appropriate for the artist. Movies in 2007 featuring acting by music artists Justin Timberlake, Beyoncé Knowles, Ludacris, Queen Latifah, Tim McGraw and others join many artists who have seen their talents grow beyond the stage of live musical performance. It is dependent on the artist manager to encourage artists to develop in creative areas that can take advantage of the brand they have developed and draw from its value in other areas of entertainment.

There are also opportunities for artist’s recordings based on the successful model Disney developed with its soundtracks and artist spin-offs from the television show, High School Musical, and the Hannah Montana television series. Both became multiplatinum selling recordings with little radio support except through Radio Disney. Seeing the Disney success, CBS corporation reactivated the CBS label imprint in late 2006. The company’s news release says “An emphasis of the new label will be to build awareness for CBS Records’ artists and songs by integrating music into CBS television series.” The company says it plans to use iTunes for music distribution and will encourage program producers to use the music of both independent and established artists in program soundtracks. (CBS, 2006)

References

Arbitron, 2006, “Format Trends,” http://arbitron.com/home/content.stm.

Ballen, Carolyn, 2007, “Looking for Sponsorship?” Starpolish.com, Advice.

Bruno, Antony, 2005, “Video Booms Online—But For Whom?” Billboard.com, October 29, 2005.

Butler, S., 2004, “The Publisher’s Place: Clause and Effect,” Billboard, May 7.

Calderone, T., 2005, “College Radio Grows Up; Nine Inch Nails Returns,” New York Times, February 6.

CBS Corporation, 2006, PR Newswire, Dec. 16, 2006, http://www.prnewswire.com.

Gordon, E., 2005, National Public Radio, “News and Notes With Ed Gordon,” June 17.

Hull, Geoffrey P., 2004, The Recording Industry, p. 147, Routledge.

Hutchison, T., et al., 2005, Record Label Marketing, Focal Press.

Leeds, Jeff, 2006, “Squeezing Money From the Music,” The New York Times, December 11, 2006.

Legrand, E., 2004, “Global Music: European Indies Rise Up,” Billboard, Aug. 14.

Macy, A., 2006, personal conversation.

Milom, Mike, 2006, “The Impact of New Business Models on Artists,” Music Row, Music Row Publications, Inc.

Morris, M., 2004, “Taking Issue: Good News For Artists,” Billboard, Sept. 25.

Palmer, Chris, 2006, personal notes.

Satzman, D., 2003, “Radio Ratings Service Again Under Fire for Methodology,” Los Angeles Business Journay, February 24 edition.