Barriers to Entry and Strategic Competition

I. INTRODUCTION

Entry is a source of competitive discipline on the industrial performance of firms. The threat of entry by new competitors puts a constraint on the latitude of existing firms to conduct their operations in ways that adversely effect consumers, while actual entry changes the structure of markets in ways that often brings about the same ends. Entry, actual or potential, can upset traditional patterns of market conduct, de-throne dominant firms, introduce new technology and fresh approaches to product design and marketing, and lead to more competitive prices.

As agreeable as these consequences of entry may seem to be in principle, there is considerable controversy over the extent to which they are achieved in practice. Observations of actual entry attempts reveal that direct entry typically has only a small effect on industry structure. Masson and Shaanan’s [1982] sample of 37 US industries over the period 1950–1966 yielded an average market share penetration by entrants of 4.5% over 6.8 years, a gain of less than 1 % per year. Yip [1982], in a sample of 59 entrants in narrowly defined markets, found a median gain of 6% (mean gain = 10%), with entry via acquisition achieving a penetration roughly three times that achieved by direct entrants. Biggadike [1976] investigated 40 entry attempts by 20 large US firms, and observed that less than 40% of these entrants achieved a penetration of at least 10% within two years. Hause and Du Reitz [1984] examined entry in Sweden over a 15 year period and observed that new entrants only managed 1.7% market penetration on average over that period.

Although these figures suggest that entrants manage to make only a fairly modest penetration into most markets, the number of actual entrants that appear in markets is often extremely large. For example, Dunne and Roberts [1986] examined about 400 four-digit US industries in 1967, 1972, 1977 and 1982, and observed 285, 347, 418 and 425 entrants on average per industry respectively. The predominant method of entry was new firms constructing new facilities (e.g. 69% in 1967 and 1982, 74–76% in 1972 and 1977), with diversifying firms numbering between 23–25% (1972, 1977) and 30% (1967 and 1982). In the UK for 1983, Geroski [1988c], observed an average of 197 entrants per three digit industry in 1983–4 (the maximum was 2556), roughly 12% of the stock of existing firms. However, the average gross penetration per entrant per industry was less than 0.1% and the average penetration for all entrants per industry was 5% (the maximum was 26.6%). Further, net import penetration averaged as much as four times the net domestic entry penetration rate.

Even more interesting, it appears from the data that the relationship between entry and exit is surprisingly close. Geroski (1988c) found that, on average, 130 firms exited per industry (the maximum was 1804), leaving a net increase in the number of firms of 67 (the maximum was 1030 and the minimum was − 34), and a net market share penetration of only 2%. There is also evidence to suggest that many of the entrants in year t entered in t − 1, t − 2 and t − 3, and, indeed, that a distressingly high percentage of entrants fail within a year of formation. Net and gross entry penetration and the net and gross number of entrants were each, however, highly positively correlated; the gross number of entrants and gross penetration were mildly negatively correlated. Fairly similar orders of magnitude were observed by Geroski [1988a] for the UK in the 1970s. Baldwin and Gorecki [1983] examined cumulative entry over the period 1970–1979 in 141 Canadian four-digit industries. All entrants post-1970 collectively acquired a market share by 1979 of about 26% on average; entry by birth accounted for 14% and entry by acquisition 12%. However high this market penetration appears to be, it must be noted that it was accompanied by a large turnover of firms; about 33% of the total 1979 population of firms were not present in 1970, and about 43% of the population of 1970 had, by 1979, disappeared (mainly by scrapping and not divestiture).

Thus, entry appears to be easy but post-entry market penetration and, indeed, survival is not. A question that this raises is whether the somewhat unimpressive market penetration by entrants reflects the existence of generally high barriers to entry in most markets or the differential efficiency advantages of established firms. Barriers to entry are often thought to reflect permanent disadvantages that entrants face, but may also be thought of as a kind of adjustment cost that entrants must overcome. Such adjustment costs can, of course, be affected by the strategic behaviour of incumbents, and this type of consideration broadens the range of potential factors which might account for what we observe. That is, it is of interest to ask whether the low post-entry market penetration that we have observed is caused by high levels of barriers or the strategic behaviour of incumbents, and why so many agents attempt entry when failure rates are high and post entry growth prospects are poor.

Although one may be interested in entry per se as an interesting phenomena to explain, the broader concern in looking at entry is, of course, with assessing market performance. If the extent of rivalry amongst active firms in a concentrated industry is too weak to generate a competitive outcome, it is important that new competitors exert a noticeable pressure on prices and productivity in order to have a positive welfare effect. In fact, many scholars believe that the mere anticipation of entry will induce incumbents to lower their prices toward more competitive levels, and thus that entry need not necessarily occur to have an effect on market performance. A benchmark in this respect has been established by Baumol et al [1982] who have applied the label ‘perfectly contestable’ to markets in which incumbent firms and potential entrants share the same technology and potential competitors can enter and exit without capital loss during the time taken by incumbent firms to change prices.

Formally, Baumol et al [1982] define a ‘perfectly contestable market’ as a market in which a necessary condition for an equilibrium outcome is that no firm can enter taking prices as given and earn strictly positive profits using the same technology as existing firms. In a perfectly competitive market, entrants can and will enter to take advantage of even transient profit opportunities at current prices. This behaviour is most reasonable when the costs of entry are completely reversible so that there are no capital losses in the event of exit. If these conditions are satisfied, a perfectly contestable market mirrors a competitive environment in which entry and exit are frictionless and barriers to entry and exit are non-existent. The assumption of identical costs insures that whenever incumbents can make profits, so can entrants, and, therefore, if a perfectly competitive market equilibrium exists, firms cannot sustain prices in excess of average cost. If more than one firm operates a positive levels of output in a perfectly contestable market equilibrium, the possibility of incremental changes in the output of a rival firm ensures that, in equilibrium, price cannot deviate from the competitive ideal of marginal cost. Thus, the outcome of competition in a market with unconstrained entry is perfectly competitive whenever the market is not a natural monopoly. If it is a natural monopoly, potential competition ensures that the behaviour of the monopolist is ‘regulated’ in the sense that total revenues are not more than total costs.

The theory of contestable markets is a useful benchmark to use in analyzing the effect of entry on market performance, but both the theory and its empirical relevance are open to question. A key assumption that is implicit in the theory of perfectly competitive markets is that capital can move with little risk of loss into and out of an industry over a period of time that is short compared to the time required for existing firms to respond with competitive price changes. If this assumption is satisfied, a firm can base its entry decision on current prices, and ‘hit and run’ can be a rational entry strategy that will police the pricing decisions of incumbent firms. However, it is unlikely that entry into any industry is perfectly reversible; so any entry attempt will probably entail some risk of capital loss if the firm should subsequently exit the industry. Farrell [1986], Gilbert [1986], and Stiglitz [1987] have argued that even if the sunk costs of entry are vanishingly small, the possibility of prompt, aggressive pricing by established firms can make entry unattractive and, by deterring ‘hit and run’ entry, permit existing firms to price at noncompletitive levels.

Empirical studies of entry also cast doubt on the contestability hypothesis. Many scholars (e.g. Bailey and Baumol [1984]) initially argued that transportation services, and, more specifically, the airline industry, were typical cases of contestable markets where fixed costs, although important, were not sunk because aircraft could be easily diverted to other uses. However, as recognized by Baumol and Willig [1986], several econometric studies have shown that the threat of entry in airline markets does not suffice to keep profits at normal levels (see, e.g., Graham, Kaplan, and Sibley [1983]; Call and Keeler [1985], Morrison and Winston [1987]). The intrinsic mobility of aircraft suggests that entry and exit may be easier in airlines than in most industries, and the fact that pricing in airlines is not determined by the threat of entry provides a good reason to question whether contestability is a force in most industries (see also Schwartz [1986] and Gilbert [1989]). Whether airlines are not contestable because airline fare schedules are capable of being changed with exceptional speed, because ground support facilities are scarce and expenditures on capital other than aircraft are largely sunk costs, or because incumbents are able to deter entry strategically through the use of non-price competitive weapons is not clear. However, the question is important enough to demand both theoretical and empirical work in the different types of entry barrier or deterrence strategies that might be relevant in any particular case.

Contestability theory is an extreme characterization of market performance that relies on the assumption that entry and exit are costless. At the other end of the spectrum is the view that infinitesimal sunk costs are sufficient to protect monopoly behaviour when incumbents respond rapidly and aggressively to entry attempts. In between, there is sufficient ground for divergent views on the effects of potential competition and on the ability of established firms to engage in strategic behaviour that deters entry. The ‘structuralist school’, typified by the work of Joe Bain [1956], maintains that the efficacy of potential competition depends on determinants of the conditions of entry such as economies of scale, technological advantages, and access to marketing or natural resources. Moreover, members of this school also argue that the conditions of entry can often be manipulated by established firms in various ways to reduce the likelihood that entry will occur and to mitigate its effects. In contrast, the ‘Chicago school’, typified by the work of Stigler [1968] and Demsetz [1982], maintains that market concentration reflects the differential efficiencies of established firms, and that most of the important types of entry barriers arise from restrictions on market conduct imposed by the government. Absent these, entry conditions are generally considered to be fairly easy and market performance is generally thought to approximate competitive outcomes fairly closely. Trying to explore the determinants of entry and to ascertain which of these several views about the effect of entry on market performance is most consistent with the facts is not an easy task, and our goal here is to introduce the reader to the basic issues involved in that choice.

We shall proceed through six stages.

Section II presents several different definitions of barriers to entry that have been proposed in the literature. Section III describes Bain’s determinants of barriers to entry and introduces the role of behaviour in the determination of the conditions of entry. We adopt Bain’s classification of entry barriers as a convenient organizational structure in which to discuss the possible sources of competitive advantage for established firms. This discussion identifies assumptions in Bain’s analysis of the conditions of entry that are essential to the predictions of the structuralist school. In particular, the assumed behavioural response of established firms to the entry of rival firms is critical to the likelihood of entry and to the ability of established firms to manipulate the conditions of entry to maintain supra-competitive profits. Our critique in Section III of Bain’s classification of the conditions of entry in terms of assumed behavioural responses of incumbent firms attempts to reduce the distinction between the predictions of the structuralist and Chicago schools to different assumptions about firm behaviour. However, the ultimate test of the theory relies on empirical observations and we draw heavily in this section on empirical studies of the conditions of entry and the effects of entry attempts. Section IV calls attention to the importance of exit barriers and specific assets in the theory of capital mobility. Section V describes the theory of dynamic limit pricing, which reflects empirical observations that the conditions of entry can affect the mobility of capital into an industry, but rarely succeed in isolating an industry from entry threats. This is followed in Section VI by a discussion of empirical models that quantify entry conditions, many of which are based on the dynamic limit pricing framework. Section VII contains a few concluding remarks.

II. DEFINITIONS OF MOBILITY BARRIERS

The concept of a ‘barrier to entry’ is more subtle than it appears to be at first sight. It has proved to be surprisingly difficult to uncover a definition of entry barriers (and more generally, of mobility barriers) that both commands wide acceptance in the profession and is empirically useful. Several alternatives have been proposed, and, in what follows, we summarize some of the more popular candidates. These definitions differ according to their emphasis on the structural characteristics of entry, the consequences of entry for economic performance, and the value of incumbency. While most of the early literature on barriers has focused on impediments to the entry of new capital into a market, we adopt the more general perspective of Caves and Porter [1977] who argue that economic performance depends on limitations to the movement of resources into, out of, or within an existing industry. Thus, we choose to use the more general term of ‘mobility barriers.’

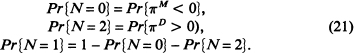

The earliest and perhaps most well-known structural definition of barriers to new competition is due to Bain [1956], who argued that the ‘condition of entry’ is determined ‘… by the advantages of established sellers in an industry over potential entrant sellers’ (p. 3), the comparison being made between the pre-entry profits of established firms and post-entry profits of entrants. Thus, a barrier to entry exists if an entrant cannot achieve the profit levels post-entry that the incumbent enjoyed prior to its arrival. Let Πi (![]() ) be incumbent i’s profit when incumbent firms i = 1, …, n operate at the pre-entry outputs

) be incumbent i’s profit when incumbent firms i = 1, …, n operate at the pre-entry outputs ![]() , and let Πe (

, and let Πe (![]() ) be the profit of an entrant at the post-entry outputs

) be the profit of an entrant at the post-entry outputs ![]() and

and ![]() . Then, entry is deterred if Πe < 0, and Bain’s measure of the height of barriers to entry for this industry is Πi − max [Πe, 0], the level of profits that can be sustained against entry in perpetuity.

. Then, entry is deterred if Πe < 0, and Bain’s measure of the height of barriers to entry for this industry is Πi − max [Πe, 0], the level of profits that can be sustained against entry in perpetuity.

Further, Bain argued that the ‘condition of entry is … primarily a structural situation … [which] describes … the circumstances in which the potentiality of competition will or will not become actual’ (p. 3; see also pp. 17–18). This additional proviso is intended to rule out transitory phenomena which affect entry from time to time (e.g. trade cycle effects, ‘innocently’ created entrant misperceptions, and so on), but it does gloss over the possibility that the effects of some structural factors on entry may depend on incumbents’ behaviour. In fact, Bain distinguished between the fundamental structural conditions which create symmetries between firms and the strategic behaviour of incumbents which exploit them, but argued that symmetries in outcome ultimately (ie. in the long run) rest on structural factors.

A complicating feature of this definition is that barriers to entry so defined are likely to be specific to the identities of both entrants and incumbents, and what may be a barrier from the point of view of one challenger may not necessarily be so from the point of view of another. For example, it may be the case that the most advantaged challenger is not a new firm, but, rather, one established elsewhere who can use certain assets to overcome what would be barriers for de novo firms. Of course, not all those firms or agents who threaten entry actually materialise as entrants in any given period. In order to assess the importance of potential and possibly unobservable entry threats, one needs to decide who the likely challengers are in principle, and how severe are the disadvantages they would suffer from were they to attempt entry. To overcome this type of problem, Bain suggested a counter-factual construction involving the ‘most advantaged’ potential competitor, leading to a definition of the ‘immediate condition of entry’ (pp. 9–11) which generates what might best be thought of as an estimate of the minimum height of barriers facing the full population of entrants.1 To construct this counterfactual entrant, one must know how the best placed agent ought to initiate its entry challenge; that is, one must identify the production, marketing, and distribution strategies that it ought to select. If, after a hypothetical entry by such a firm using such strategies, one finds that it cannot do as well as the incumbent was doing, then, according to Bain, a barrier is said to exist.

B. Stigler and the Chicago School

It is useful to contrast Bain’s structural view of barriers to entry with that of Stigler [1968], who proposed that: ‘… a barrier to entry may be defined as a cost of producing (at some or every rate of output) which must be borne by firms which seek to enter an industry but is not borne by firms already in the industry’ (p. 67). Formally, if Ci(x) and Ce(x) are an incumbent’s and entrant’s cost of producing x, Stigler’s measure of the height of a barrier to entry is Ce(x) − Ci(x). The primary conceptual difference between Stigler and Bain is that, in the former case, the entrant and incumbent are compared post-entry: a barrier exists if the two are not equally efficient after the costs of entering the industry are taken into account. Bain’s emphasis on the conditions of entry assign an entry barrier to any industry in which structural conditions exist that permit an established firm to elevate price above the minimum average cost of potential entrants. Stigler considers an entry barrier to exist only if the conditions of entry were less difficult for established firms than for new entrants.

There are some difficulties with Stigler’s definition. His reference to ‘some or every rate of output’ makes the definition ambiguous. Should the barrier to entry be measured at the point of minimum efficient scale, at the incumbent’s present output, or the entrant’s expected output? These quantities are likely to differ, and, therefore, Stigler’s measure of the size of the entry barrier can be arbitrary.2 Exactly what Stigler means by ‘costs that must be borne’ is not clear. Does this include costs incurred by incumbent firms that have become sunk costs? Stigler’s measure is also, as in Bain, specific to the identity of both entrant and incumbent. His focus on costs appears to ignore revenue-dependent sources of entry barriers, such as product differentiation, but, in fact, Stigler’s definition is generalisable in a straightforward way to include whatever costs an entrant might have to bear to overcome a product differentiation advantage of an incumbent firm. According to Stigler’s (somewhat generalized) definition, a barrier to entry would exist if the new firm has to overcome more consumer resistance than did the established firm. The height of an entry barrier would be the additional cost an entrant would have to bear in order to produce the same revenue as an established firm.

The practical distinction between Bain and Stigler lies in the evaluation of economies of scale as a barrier to entry. Economies of scale are a barrier to entry according to Bain because if scale economies are important, then entry is likely to lead to a price reduction, and, even if entry were successful, profits to the entrant post-entry are likely to be lower as a consequence than they were to the incumbent pre-entry. However, under Stigler’s definition, scale economies do not represent a barrier to entry if they imply penalties from suboptimal levels of production that are the same for both established firms and potential entrants. According to Stigler, if an entrant incurs a higher cost because it must produce at a lower level of output, the cost disadvantage is a consequence of demand conditions in the market and not the existence of a barrier to entry. ‘… some economists will say that economies of scale are a barrier to entry meaning that economies explain why no additional firms enter. It would be equally possible to say that inadequate demand is a barrier to entry’ (Stigler, 1968, p. 67).

C. A normative definition of barriers

Both Bain and Stigler’s approach to the definition of a barrier to entry is positive. Their definitions do not address the welfare consequences of entry, but, instead, characterize conditions that impede entry. Von Weizsacker has attempted to approach the definition of barriers to entry from a normative point of view. His concern is not with the factors that impede the mobility of capital, but rather with ‘socially undersirable limitations to entry of resources which are due to protection of resource owners already in the market’ (von Weizsacker [1980], p. 13). Von Weizsacker’s definition of barriers to entry is a qualification of the definition proposed by Stigler. Von Weizsacker defines a barrier to entry as ‘a cost of producing (at some or every rate of output) which must be borne by firms which seek to enter an industry but is not borne by firms already in the industry, and which implies a distortion in the use of economic resources form the social point of view.’ (. 400) The definition implies that there could be too little entry due to excessive protection, and also that there could be too much entry due to too little protection.

Consider the following simple example. Suppose a large number of firms have a cost function C(x) = mx + F, where F is sunk if entry occurs. The inverse demand function is P(X) = a − bX, where X is total demand and is equal in equilibrium to the total supply by all firms. The first best allocation in this market calls for one firm producing at an output at which P = m. However entry will occur until the profit of the (n + 1)st firm is negative. Suppose all firms that are active in the industry behave as Cournot competitors. Each firm produces (a − m)/(b(n + 1)), total output is n(a − m)/(b(n + 1)), and there are too many firms relative to the first best allocation. Of course, adding more firms to the market increases total output, but, relative to the total output with n − 1 firms, total output increases by only (a − m)/(bn(n + 1)), which is only 1/n of the sales of the nth firm. It is not difficult to show that if one could control only the number of firms in the market, the number that maximizes total economic surplus would be less than the number of firms in a market equilibrium. New entrants ignore the negative externality that they impose on existing firms, and, thus, there is too much entry.3 Conditions that increase the cost of entry into this market could increase economic surplus and would not be barriers to entry from von Weizsacker’s normative perspective.

If an activity creates positive externalities, the entrepreneur organizing it can be insufficiently protected by property rights so that there would be insufficient incentive to devote resources to this activity. For example, if patents do not provide enough protection for investors, too few resources would be devoted to investment in R & D. On the other hand, if an activity causes negative externalities, it can be excessively protected. Excessive patent protection, for example, could result in excessive inventive activity for the same reason. According to von Weiszacker, a barrier exists only if the equilibrium involves insufficient entry relative to the social optimum. Demsetz [1982] has further extended this normative approach to the evaluation of barriers to entry by arguing that, in many cases, what is called an entry barrier is an endogenous response to consumer preferences and supports an efficient allocation of resources. For example, the number of brands may be limited by consumers’ ability to evaluate different alternatives. Entry is restained by consumers’ reluctance to assume additional information cost. Rather than allowing resources into high profit industries, it might be better to take into account the role of externalities, information and transaction costs, and to consider entry barriers as a valuable second best answer to real world frictions: ‘… existing firms have an advantage insofar as their existence commands loyalty … (that is barriers) reflect lower real cost of transacting, industry specific investments, or reputable history (which is) an asset to the firm possessing it because information is not free …’ (pp. 50–1).4

The major strength of this approach—it’s explicit focus on the normative consequences of entry—is also the source of its major weakness. It is difficult enough to measure barriers to entry (defined à la Bain or Stigler) without adding an additional layer of normative complexity, and it is probably simpler to evaluate barriers in two explicit steps: first, measure their height, and then, second, evaluate their consequences for welfare.

In contrast to the normative approach to the determination of mobility barriers, Gilbert [1989a] concentrates solely on the advantages that accrue to established firms. According to Gilbert, a mobility barrier exists if firm earns rents (which may be negative) as a consequence of incumbency. Let ![]() be the profit of the ith incumbent firm in industry k and let

be the profit of the ith incumbent firm in industry k and let ![]() be the profit that firm i could earn if it were to abandon industry k and enter an alternative industry 1. Included in the set of alternative industries is the null industry of doing nothing, and this set could include k, in which case the incumbent would be a new entrant in its own industry. In the latter case, the hypothetical exit and re-entry should occur after remaining incumbent firms have had time to adjust to the exit of the firm. An incumbency rent exists if

be the profit that firm i could earn if it were to abandon industry k and enter an alternative industry 1. Included in the set of alternative industries is the null industry of doing nothing, and this set could include k, in which case the incumbent would be a new entrant in its own industry. In the latter case, the hypothetical exit and re-entry should occur after remaining incumbent firms have had time to adjust to the exit of the firm. An incumbency rent exists if ![]() > max(1)

> max(1) ![]() , and the magnitude of this difference is a measure of the incumbency rent. This definition has no relation to the consequences of entry or exit for economic welfare. The emphasis is on the role of history and how that affects relative profits; an entry barrier exists if a firm earns a premium by virtue of its being established in the industry. An exit barrier exists if an incumbent firm could earn more if it could leave the industry.

, and the magnitude of this difference is a measure of the incumbency rent. This definition has no relation to the consequences of entry or exit for economic welfare. The emphasis is on the role of history and how that affects relative profits; an entry barrier exists if a firm earns a premium by virtue of its being established in the industry. An exit barrier exists if an incumbent firm could earn more if it could leave the industry.

This definition is similar to that used by Bain, but is has some important differences. It does not depend on the identity of an entrant firm, because only the incumbent firm’s technology is considered. There are, however, as many values of incumbency as there are incumbent firms, and these values may span a wide range. It also deals with the question of opportunity costs of scarce factors. If the incumbent were to abandon the industry, one option it has is to sell its factors of production or to use them in a different activity, and this consideration means that they must be valued at their opportunity costs. A potential criticism of this definition of incumbency rents is that obvious sources of competitive advantage are likely to be discounted because they have values that capitalize monopoly profits. For example, a key patent need not be a source of incumbency rents if it can be sold for a price that equals its value to the current owner. But, as Section III.B discusses more fully, there are reasons not to call a patent an entry barrier if it has an opportunity cost equal to its value to the patentee, any more than a scarce piece of land should be considered a barrier to entry.

Most of the literature on capital mobility limits attention to the flow of physical capital into and out of an industry. Entry is ‘easy’ if an entrepreneur can move factors of production into an industry and earn profits that are comparable to the profits earned by incumbent firms. However this ignores the possibility of entry through acquisition of existing assets. Most of the entry literature has tended to ignore this avenue of entry, perhaps because entry by acquisition does not add to the productive resources of the industry. However, the opportunity to acquire an existing firm is an alternative to direct entry and this action can have real consequences for economic performance (see Gilbert and Newbery [1988]). The definition of barriers to entry as a rent to incumbency can incorporate entry by acquisition if one of the alternative activities available to an incumbent firm is the direct sale of its corporate assets. One should, however, note that the price of entry by acquisition need not be less than the price of direct entry by new capital investment in an industry. Entry by acquisition can be impeded by the managers of incumbent firms, who may place an asking price on corporate assets that exceed their value to new management. A reason why managers may refuse to sell out even if ‘the price is right’ is that managers have firm-specific capital that is invested in their firm. But, as Gilbert and Newbery [1988] argue, potential entrants may be able to acquire incumbent firms at favourable terms by threatening to enter as rivals if the target firms refuse to sell.

This review of the different approaches that have been taken to the identification and measurement of mobility barriers reveals that there is considerable controversy over what is a barrier to entry and how it should be measured. Economies of scale can be a significant barrier to entry according to Bain, insignificant according to Stigler, and von Weizsacker might argue that economies of scale do not prevent enough entry from occurring! In what follows, we will attempt to resolve some of the differences between the conclusions of Bain and Stigler, showing how the consequences for capital mobility of factors such as economies of scale depend critically on the behaviour of incumbent firms. This is consistent with our view of barriers to capital mobility as determining rents that are derived form incumbency. The size of these rents will depend on the behaviour of established firms. We will not attempt to perform a welfare analysis of barriers to capital mobility, but will remain content to alert the reader to the distinction between the positive and normative consequences of factors that might impede the flow of capital into and out of markets.

III. DETERMINANTS OF THE CONDITION OF ENTRY

Bain [1956] identified economies of scale, product differentiation, and absolute cost advantages of established firms as the major determinants of the conditions of entry. This taxonomy provides a convenient jumping-off point for a discussion of sources of barriers to capital mobility, and we shall consider each type of barrier in turn. However, it will be evident that the extent to which these factors actually impede capital mobility depends on industry behaviour, and, therefore, that they cannot be evaluated without taking into account the strategic actions that are available to established firms. The interactions between Bain’s sources of barriers to capital mobility and firm behaviour also imply that established firms may be able to enhance the deterrence value of structural barriers to capital mobility by engaging in strategic behaviour designed to make entry more difficult. Some of the ways in which this can be accomplished, and some of the obstacles to strategic exploitation of mobility barriers, are discussed below.

A. Barriers and strategic behaviour

Potential competitors will be reluctant to enter an industry if they anticipate that incumbents will respond to entry by competing aggressively for market share. Sophisticated incumbents who anticipate potential competition may attempt to signal an aggressive stance, perhaps by cutting prices before entry occurs (e.g., see the classic paper by Modigliani, [1958]). This type of strategy—often called ‘limit pricing’—captures the very reasonable notion that the presence of potential competitors can have an effect on price determination, and that strategic actions undertaken by incumbents may pre-empt and thus deter entrants. However, while intuitively appealing, the problem with this type of argument is that it is a little too simple. In the presence of complete information, there is no reason why the price that prevails before entry should have, by itself, an influence on the decisions of a potential entrant. The success of such a strategy depends on the extent to which potential rivals correlate pre-entry behaviour to post-entry profits. Streeten [1955], for example, argued that ‘the absence of excess profits will have an entirely different effect upon rivals contemplating entry according to whether it indicates an absence of profit opportunities, or a reluctance to exploit them. The latter will only have the effect of the former if it succeeds as a bluff … If we assume that potential entrants see through the bluff, the absence of excess profits will be no deterrent to entry’ (p. 261). Put otherwise, the pre-entry strategic action is unlikely to create an advantage for the incumbent in a situation where one does not already exist. Rather, it is designed to exploit structural asymmetries between entrant and incumbent, particularly in situations where the size of these are not well understood by the entrant.

The use of price as a signal of post-entry market conditions in conditions of incomplete information has been discussed more recently by Salop [1979] and posed in game-theoretic form by Milgrom and Roberts [1982a]. In the Milgrom and Roberts model, uncertainty is limited to entrants’ knowledge of an incumbent’s marginal production cost. Entry is assumed to be profitable if the incumbent has a high cost, but unprofitable if its cost is low, and they assume that the expected value of entry is negative, so entry would occur only if the potential entrant anticipates that the incumbent has a high cost. They show that there may exist a ‘separating equilibrium’, in which the incumbent’s pre-entry price is a function of its marginal production cost. Only in such an equilibrium does price serve as a signal of post-entry profitability. Although entry occurs if an incumbent is high cost in a separating equilibrium, the incumbent’s price is lower as a consequence of entrants’ imperfect information. Hence they conclude that the incumbent engages in limit pricing, but that it does not prevent entry when entry would be profitable. In effect, the purpose of limit pricing in the Milgrom and Roberts model is to prevent potential rivals from thinking that the incumbent firm has even higher costs than it actually has.

The consequences of imperfect information for entry deterrence depend on the information structure of the game between entrants and incumbents. Matthews and Mirman [1983], Saloner [1981], and Harrington [1984] describe signalling models in which prices are noisy signals of market conditions. As a result of exogenous disturbances, a potential entrant is not able to determine post-entry market conditions with certainty given an incumbent’s pricing decision. These models show that, in a noisy information model, the probability of entry can be an increasing function of an incumbent’s price (which provides a theoretical foundation for models of limit pricing such as Kamien and Schwartz [1971] and Gaskins [1971] discussed below in Section V). Moreover, the probability of entry depends on the information structure of the model, and may differ from the probability of entry that would occur with perfect information about market conditions. An extension of the Milgrom and Roberts model by Harrington [1984] illustrates the importance of these points. Harrington allows the entrant’s cost function to be uncertain and positively correlated with the incumbent’s cost (not unreasonable if they use similar production technologies). If the potential entrant believes its costs is high, it will stay out of the industry. With the different twist of positively correlated costs, the incumbent has an incentive to price high in order to signal a high cost and thereby convince the entrant that its cost is high too. In order to discourage entry, the incumbent prices high, not low!

Related to the theory of price as a signal of the conditions of entry are dynamic models of repeated games in which established firms can influence entrants’ expectations of post-entry competitive conditions through their choice of pre-entry pricing strategies. These games include Selten’s [1978] discussion of pricing by a chain store and the reputation models developed by Kreps and Wilson [1982] and Milgrom [1982]. These models rely on some degree of asymmetric information about incumbents’ behaviour in the post-entry market. A potential entrant may be unsure as to whether established firms will accommodate new entry or price aggressively in response to an entry attempt. These models show that even a small prior expectation by the entrant that an incumbent will respond to entry in an aggressive manner may be sufficient to encourage an incumbent to take an aggressive stance and reinforce the entrant’s expectations.

Strategic behaviour of incumbents is essential to the consequences for entry of most structural characteristics of markets. For example, suppose all firms have the cost function C(x) = mx + F. If industry behaviour is such that two or more firms act as perfect competitors, then entry would result in price equal to marginal cost and no firm would earn a profit. The only sustainable market structure would be a monopoly. Contrast this with a situation where incumbent firms always chose to keep their prices unchanged in response to entry. In the latter case, if price exceeds average cost, entry may be feasible even in an industry that is a natural monopoly. Thus, a theory of barriers to entry cannot be constructed in isolation from a theory of oligopoly behaviour.

B. Scale economies, sunk costs and limit pricing

According to Bain, economies of scale create problems for entrants in two ways, via a ‘percentage effect’ and an ‘absolute capital requirements effect’ (Bain, [1956], p. 55). The former depends on the size of the minimum efficient scale plant relative to the extent of the market, and occurs for large minimum efficient plants (MEP hereafter) because, if the entrant is to enter at efficient scale, the ‘… addition to going industry output … will result in a reduction of industry selling prices’ (p. 53) for any reasonable response by incumbents. If entry occurs at less than efficient scale, the entrant will face a cost penalty depending on the slope of the cost curve at sub-MEP scales. Note that implicit in Bain’s conclusion about the percentage effect of large MEP plants is the prescription that incumbents firms will not accommodate entry by scaling back their own production by an amount equal to the production offered by new entrants. Under the hypothesis of perfectly contestable markets, a potential entrant conjectures that market prices would be unaffected by its entry, which corresponds to a situation in which established firms do accommodate new entrants. In contrast, a competitive response to entry implies an increase in post-entry output. The key question is, therefore, the extent to which potential entrants expect that incumbent firms will act to hold onto market share.

Bain’s ‘absolute capital requirements effect’ arises from the large investment outlays necessary to build an appropriate sized plant (given capital market imperfections), and the size of the disadvantage so created is liable to depend on the absolute size of MEP. Implicit in this source of barrier to capital mobility is a view that new entrants will encounter difficulties in raising capital, locating and training a qualified workforce, and developing the inventories and distribution channels needed for entry at MES. These differential cost effects are discussed in more detail in the next section.

Estimating scale-related entry barriers involves generating estimates of the cost per unit that could be achieved at different output scales by the most advantaged entrant (i.e. one using the best possible organization of production currently available and minimizing factor expenditures). The major problem is that ‘the best possible’ is often difficult to observe. What can be easily observed are the actual unit costs of incumbent firms or the actual distribution of plant sizes, and a great temptation exists to infer ‘ought’ (i.e. the cost of the best-practice plant) from ‘is’ (i.e. those actually prevailing)5. What is needed to make this alternative approach work is the ability to isolate and identify those existing plants which most nearly approximate the best production process that can be implemented under the circumstances. The four following techniques all follow this procedure, making the implicit assumption that one or all existing firms are efficient, and that the best an entrant can do is to replicate their actions.

The simplest and most direct principle of plant selection originated with Bain (1956, p. 69), who postulated that: ‘… the largest plants are likely to be at least as large as is required for maximum efficiency …’, because the firms operating the largest plants are typically multiplant firms, and these firms have the option of building a plant to optimal size before they elect to build another plant at a different location. Of course, such a criteria does not give an estimate of MEP if the true average cost curve has a substantial flat segment. What is more, it is not obvious how large a firm must be in order to be free from constraints in the choice of plant size, nor whether such firms are sufficiently disciplined by market forces to seek the true minimum cost position; further, mistakes can lead to plant sizes that are too large. Consequently, it should not come as too much of a surprise to find that this approach generates a fairly wide range of predictions of MEP depending on different notions of ‘how large is large, but still efficient’. Bain computed the average size of all plants in the largest Census of Production size class, and numerous others have been introduced subsequently and used over the years: the average industry plant size as a proxy for MEP, the mid-point of the size distribution (i.e. that plant size above which is produced 50% of industry output), and the average size of the largest plants responsible for 50% of industry output.6 Lyons [1980] suggested an alternative proxy which is an interesting contrast to these five. Using a rather stronger argument about plant selection than Bain, he concluded that firms producing at the true MEP will be equally likely to operate one or two plants, and thus that MEP can be identified by looking at the actual plant sizes of those firms who, on average, operate about 1.5 plants.

As an alternative to the direct measurement of plant cost functions, one can use a ‘selection of the fittest’ principle to identify the efficient size class from the existing size distribution of firms. This approach identifies efficiency with the ability to survive and prosper: ‘… an efficient size of firm is one that meets any and all problems the entrepreneur actually faces …’ (Stigler, [1958], p. 73). There are obviously several empirical criteria one could use to pick out such ‘winners’. They are likely to be relatively profitable (and probably persistently so), and so one could choose MEP as that size of firm whose market share yielded the highest profit (this could be read off regressions such as those of Shepherd [1972], although Shepherd does not use this interpretation; however, see Scherer, [1980], p. 92). Alternatively, efficient firms could be those with high growth, investment, share prices and so on. However, it is generally agreed that the most plausible approach is to trace developments over time in market shares associated with different sized firms, (for obvious reasons, it is difficult to apply this technique to plants), and what have come to be labelled as ‘survivor technique estimates’ are generated by the following rule proposed by Stigler [1958]: ‘… if the share of a given (size) class falls, it is relatively inefficient, and in general is more inefficient the more rapidly share falls’ (p. 73), (pp. 75–6). Thus, the procedure defines L-shaped cost curves whose ‘kink’ (MEP) is determined by that size class whose market share does not decline. In principle, such estimates have little to say about efficiency as it is conventionally used (they refer to: ‘… the decisive meaning of efficiency from the viewpoint of the enterprise. Of course, social efficiency may be a very different thing’, p. 73), they are liable to be accurate indications of entry problems only for entrants who could exactly replicate the competitive conditions of incumbents in the size class they choose to enter, and they are liable to confound market power and cost effectiveness. In practice (e.g. Saving [1961], Weiss [1964], Rees [1973]: for a critique, see Shepherd [1967]), such estimates of MEP are not always stable over time, are not always unique, are very sensitive to market definitions, and problems can arise because the notion of ‘survivability’ is not easy to define precisely (is a 2% market share decline random noise, measurement error, or indicative of a real loss of competitive edge?).

Progress from the quality of the proxies generated thus far can only come from better, more extensive data used with perhaps more precise conceptualizations of how efficiency varies with scale. Two possibilities in this direction are ‘statistical cost estimates’ and ‘production or cost function estimates’. The former construct estimates of industry cost functions from observations on the unit costs of plants producing different output rates (e.g. Johnston [1960] and many others). Aside from a myriad of difficulties to be faced in accurately measuring costs, there is a major conceptual problem involved in assuming that all incumbents operate on the common average cost curve so estimated (i.e. the principle of plant selection implicitly involved is that all industry incumbents are efficient). While this may not bias estimates of MEP, it is certain to give a fairly murky picture of the cost disadvantages of producing at sub or super optimal scale. Thus, for example, high cost observations of small plants may reflect a steeply sloped common industry cost curve, or may reflect the inefficiency of those firms not cost competitive enough to gain a healthy market share. To take a second example, in a homogeneous goods industry where all firms operate as Cournot competitors with the same constant average cost function, one will observe one point on the cost curve, and this creates the erroneous impression of a single unique production capacity plant. The general point (which, of course, applies to all of the proxies discussed thus far) is that the use of observed costs (or plant sizes) to infer best practice costs cannot proceed without a critical awareness of how the data were generated. Much the same problem plagues production or cost function estimates which use basic data on factor inputs and expenditures to generate estimates of MEP given a priori assumptions on the industry wide commonality of production techniques, and its characteristics.7

All of the techniques discussed above share the common weakness identified at the outset; viz that in order to apply these numbers to describe the entry problems facing the most advantaged entrant, one has to imagine that certain (or all) incumbents are efficient, and that entrants can do no better than to replicate the decisions of these firms. This is an important shortcoming, and it is necessary to consider the far more expensive alternative of direct measurement of MEP. Here one has little choice except to simply work out from basic engineering principles what would be the optimal plant size (given current technology, factor prices, and so on) for an entrant to aspire to, and how large the various cost penalties associated with non-optimal scale are. Provided that such information is actually available at a not too unreasonable cost to potential entrants, one could imagine an entrant doing exactly this and, for this reason, one might argue that such ‘engineering’ estimates ‘… undoubtedly provide the best single source of information on the cost-scale question’ (Scherer, [1980], p. 94; for applications and extensive discussions of the technique, see Bain, [1956], Scherer et al., [1975], and Pratten, [1971]). From the work which has thus far been done (on samples biased towards industries believed to have large MEPs), it seems that MEP is fairly modest relative to market size, at least in economies like the U.S. with large low transport cost markets, or those with well developed export links (Scherer, [1980], pp. 96–7). Given at least a moderate target market share by entrants, entry difficulties due to scale economies in production or distribution may well be more the exception than the rule.8

Scale advantages can also arise on the demand side, from advantages which large firms enjoy in generating revenue. An interesting possibility in this respect arises in connection with advertising, and the debate on this particular subject is extensive (e.g. see Comanor and Wilson [1979]). Economies of scale may arise from thresholds in the effect of advertising on sales, from variations in rate structures with respect to size of advertising budget, and from variations in the effectiveness of different media (e.g. television vs the rest) whose use requires expenditures of different orders of magnitude. Evidence from both beer [Peles, 1971] and cigarettes [Brown, 1978] lend support to the notion that such economies exist. Brown, for example, calculated that a new entrant would be required to achieve an advertising-sales ratio nearly 50% higher than that of incumbent firms to enable it to compete on a par.

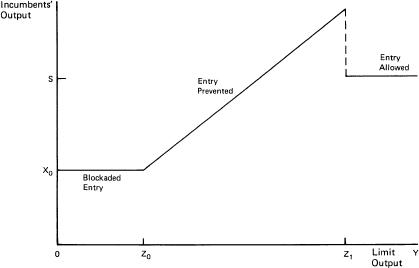

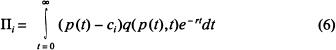

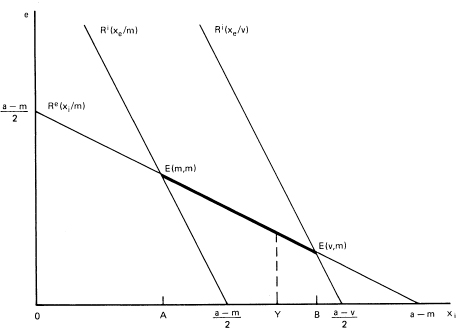

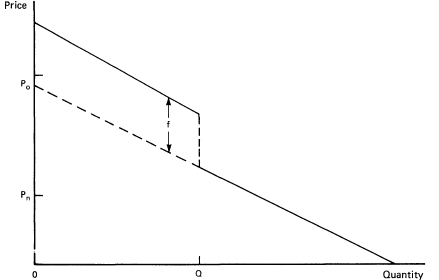

Estimates of MEP that are large or small in any particular market do not necessarily imply that barriers to mobility are large or small in that market, partly because the cost disadvantage of operating at sub-MEP scale may be only slight, and partly because the effects of entry on price at efficient scale depend on incumbents’ behaviour. Bain [1956], Sylos–Labini [1962], Modigliani [1958], and others have investigated the ability of incumbent firms to exploit the scale advantages of the ‘percentage effect’ originating from MEP, and their work has led to the classic ‘limit-pricing’ model of behaviour by a dominant firm or cartel. The model, which was originally proposed by Bain and Sylos–Labini and formalized by Modigliani (henceforth referred to as the BSM model), assumes that a dominant firm or cartel establishes an output which potential entrants expect will continue to be produced if entry occurs. This assumption, which the authors proposed as a conservative conjecture on the part of potential competitors, implies that new entrants face a residual inverse demand P(Xo + Xe), where Xo is the unchanged output of the dominant firm and Xe is the entrant’s output. In effect, the entrant’s inverse demand function is ‘shifted to the right’ by the amount Xo, and this gives incumbents the opportunities to affect the entrant’s expected post-entry profits. A firm cannot profit from entry if, given the incumbent output and the expectations of the potential entrant, the market price is below the entrant’s average cost at any feasible level of output. This condition is illustrated in Figure 1.

The BSM model assumes that potential entrants are pessimistic in their entry expectations. They act on the belief that incumbent firms will be able to maintain their pre-entry sales if entry occurs. Bain labels a situation where the optimal output of incumbent firm(s), without regard to the threat of entry, is sufficient to make entry unprofitable, as one of ‘blockaded’ entry. A situation where incumbent firm(s) earn higher profits by choosing an output at which entry is prevented than they would earn if entry is allowed, is called ‘effectively impeded’ entry. The converse is ‘ineffectively impeded entry’.

The ‘limit price’ and ‘limit output’ are determined by demand and the entrant’s technology. Figure 2 shows the incumbents’ optimal output as a function of the limit output, Y.9 Region B in Figure 2 corresponds to blockaded entry, which occurs if the incumbents’ optimal output ignoring entry, Xo, exceeds the limit output, Y. The smallest limit output for which incumbents maximize profits by allowing entry strictly exceeds Xo. This follows because if entry occurs, the new firm produces a strictly positive output, which means that incumbent firms suffer a non-negligible loss of market share. Thus, incumbent firms are willing to incur losses relative to the unconstrained output in order to deter entry. If the limit output were equal to Xo, the optimal output ignoring entry, the cost to incumbents of increasing output to deter entry would be nil. By continuity, the limit output at which entry is allowed must strictly exceed Xo. Moreover, at the limit output for which the incumbent is indifferent between preventing and allowing entry, total output is strictly lower and price is strictly higher when entry is allowed.

This condition must hold because, if incumbent firms allowed entry to occur, they would lose market share. In order to be indifferent between having all of the market (with no entry) and part of the market (with entry), the price must be higher in the latter case. Thus, when established firms act to limit entry of new competitors, price should be lower, and economic welfare may be higher, than if established firms accommodated new entrants.

FIGURE 2 Zones of strategic behavior.

The assumption that incumbent firms can convince potential entrants that they will continue to produce at the pre-entry output level regardless of whether or not entry occurs was recognized as crucial early in the development of the theory of limit pricing. One can easily see that alternative assumptions profoundly affect the scope for limit pricing. For example, suppose that the potential entrant conjectures that if it were to enter the market, it would compete with established firms as a Cournot oligopolist. In making its decision to enter, the entrant cares only about profits in the post-entry game. It will chose to enter if the incumbents’ Cournot equilibrium output is less than the limit output, and will stay out of the market otherwise. If the established firm’s pre-entry price and output have no bearing on the equilibrium of the post-entry game, they will properly be disregarded by the potential entrant. The incumbent might as well set the monopoly price in the pre-entry period, for any other choice would sacrifice profits in the pre-entry period with no consequences for the likelihood of entry. Limit pricing will not occur. Of course, Cournot competition is not the only plausible scenario for the post-entry game. Spence [1977] examined a limit-pricing model in which he assumed that the post-entry game was perfectly competitive, which implies that the post-entry price equals (the lowest) marginal cost of the competitors. Again, pre-entry output is no longer an indication of post-entry profitability and the limit pricing model breaks down. Spence argued that incumbent firms may invest in additional production capacity in order to lower their post-entry marginal cost and therefore lower the post-entry price and profitability for the entrant. Because the pre-entry price is not a signal of post-entry profitability, the incumbents can choose the monopoly price in the pre-entry stage, given their production costs. These alternatives to the BSM model differ in their assumptions about the behaviour of the firms in the industry, and, in particular, about the beliefs that firms have about how their rivals will behave. As these beliefs should be based on realistic expectations of the consequences of entry decisions, it is interesting to ask how established firms can convince potential entrants that actions such as limit pricing which are intended to discourage entry will indeed make entry unprofitable if it is attempted. We explore two different ways in which established firms can send credible signals to potential rivals that discourage entry. The first derives from the characteristics of the entrant’s production technology, while the second depends on asymmetric information about production costs.

The output commitment in the BSM model is credible if established firms would choose to maintain their pre-entry total output if entry should occur. The ability to credibly commit is related to the concept of ‘subgame perfection’ in the theory of dynamic games. A strategy, which defines the reaction of firms to the actions of their competitors and the random occurrences of nature (see Selten [1975] and Kreps and Wilson [1982]). Included in this possible spectrum of games is the game corresponding to the entry of a new competitor. Thus, a strategy in which established firms act to maintain their collective output in the face of entry is a subgame perfect equilibrium strategy (and hence credible) if it is an equilibrium choice of the established firms whether or not entry occurs.10

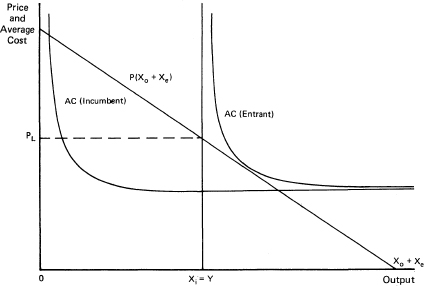

When capital expenditures, once made, become irreversible or ‘sunk’ in the next period, an established firm might be able to commit to producing an output that it could not sustain as an equilibrium if its first period expenditure were reversible. The existence of sunk expenditures has the effect of lowering the incumbent’s marginal cost for any output below the full capacity level of output, which, in turn, discourages the firm from cutting output in response to entry. This argument is due to Dixit [1981], who proposed the following simple model. Dixit allows production cost to depend on installed capacity, K, in addition to output. Both are measured in the same units (e.g. tons/yr of output and tons/yr of capacity). Capacity has a cost of s per unit and, once installed, has no alternative use. The cost function is

FIGURE 3 Marginal cost function with sunk costs.

![]()

The marginal cost function (1) is shown in Figure 3. Marginal cost is v whenever there is excess to capacity, and v + s when capacity and output are equal. F remains as a reversible fixed cost.

The incumbent has sunk costs of sK, but a potential entrant has no sunk costs because it has not yet invested in capacity. As the entrant will built just enough capacity to produce its anticipated output, the entrant’s cost function is simply

![]()

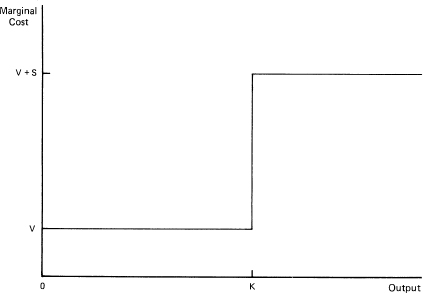

The Cournot-Nash reaction functions corresponding to the cost functions in (1) for the incumbent and (2) for the potential entrant are shown in Figure 4. The reaction function labelled Ri(xe/m) is the incumbent’s reaction function when the firm has no excess capacity (that is, when K = xi), so that its marginal cost is v + s = m. If K > xi, the incumbent’s marginal cost is only v and its reaction curve is Ri(xe/v), which is to the right of the reaction function with no excess capacity. The reaction function that the incumbent is ‘on’ depends upon the installed capacity and its output xi. The entrant has no installed capacity. Therefore, with respect to its entry decision, the entrant faces a marginal cost of v + s, which includes the cost of capacity. The entrant’s reaction function is shown as Re(xi/m) in Figure 4.

If the incumbent has no installed capacity, its reaction function is Ri(xe/m) and the Cournot equilibrium occurs at the point E(m, m). If the incumbent holds excess capacity, its reaction function is Ri(xe/v) and the Cournot equilibrium occurs at E(v, m). Depending on the incumbent’s choice of capacity, K, the post-entry equilibrium can be any point between A and B on the entrant’s reaction function. The point A corresponds to the incumbent’s equilibrium output at E(m, m). This is the smallest output that can be sustained by the incumbent as a Cournot equilibrium. The point B corresponds to the incumbent’s output at E(v, m) and is the largest output that can be sustained as a Cournot equilibrium. Outputs intermediate between A and B are equilibria for corresponding capacity investment, K. If, given an investment in capacity, K, the equilibrium output that results if a firm entered the market is such that the entrant would not break even, a rational firm would choose to stay out of the market. Thus, prior capacity investment is a way to make an entry deterring limit output ‘credible.’

Sunk cost in the Dixit model allow an established firm to maintain a more aggressive response to actual entry than would be possible if costs were not sunk. Dixit also shows the potential entry may encourage an incumbent firm to invest more in irreversible capital. This has the effect of increasing the incumbent’s post-entry equilibrium output, while lowering the entrant’s post-entry equilibrium output and the post-entry price. In manner similar in spirit to BSM limit pricing, the incumbent invests in capital to deter entry, and, as a result, pre-entry output is higher and pre-entry price is lower than the corresponding monopoly values. The analogy with the classical limit pricing model is even closer because, in Dixit’s example, sunk capital allows the incumbent to commit to a fixed output between A and B in Figure 4, and it would be correct for an entrant to assume that the incumbent’s output will remain unchanged in response to entry, as assumed in the BSM model.

FIGURE 4 Reaction functions and equilibria with capacity investment.

If capital expenditures were completely reversible, the incumbent firm would have the same cost function as the entrant and the incumbent would be unable to prevent entry by expanding output. Note that the possibility that sunk costs might contribute to the risk of an entry decision (because capital investment might be stranded in an unprofitable industry) is not a factor in the Dixit model. By assumption, there is no uncertainty. Entry occurs if it is profitable and entry is prevented if it is not profitable. Thus, the entrant is not at risk in the Dixit model.

According to the definition of mobility barriers advanced in Section II.D, sunk costs are a potential barrier to exit by the established firm, and in the Dixit model this has consequences for the entry decisions of potential rivals. Sunk costs imply that an established firm would tolerate a lower level of profit than it would accept if it were to invest capital in a new venture. The difference between the profit an established firm would earn after entry (after deducting sunk costs) and its profit if it could move capital out of the industry is a measure of the magnitude of the exit barrier. With the technology assumed in the Dixit model, the implication of this exit barrier is that the established firm (with its back to the wall, so to speak) can be an aggressive competitor to a new entrant. Knowing this, the entrant may be better off staying out of the market.

Sunk costs are a Dixit barrier for the established firm that permits the firm to act strategically and capitalize on the entrant’s need to operate at a large scale in order to make a profit. Sunk costs are not themselves an entry barrier in the Dixit model, but they allow an established firm to exploit convexities in entrants’ costs.11 Capital investment can be an effective entry deterrent in the Dixit model even if the potential entrant has the same cost function as the incumbent, or even if the entrant has lower cost, because the extent to which costs are sunk plays an important strategic role in permitting the established firm to commit to a level of output that it would maintain if entry were to occur. The established firm’s technology with its sunk capital cost is a mechanism by which the firm can sustain the aggressive market share assumptions implicit in the BSM model of limit pricing. In this respect, the Dixit model is a theoretical construction that supports Bain’s structural view of economies of scale as a barrier to entry. In the same way, Dixit’s model contradicts Stigler’s definition of a barrier to entry, which relies on symmetries in the pre-entry costs of established and new firms. Unless one distinguishes costs according to whether or not investment is sunk, the fact is that entry prevention can be achieved in the Dixit model even if the entrant and established firms share the same technology.

Strategic incentives for entry deterrence depend on the correlation between actions which the incumbent can take today and competition in the post-entry game tomorrow. By investing in sunk capital, the incumbent can lower its marginal cost and increase its post-entry equilibrium output. Actions which make the post-entry game more (less) competitive for the incumbent would increase (decrease) the scope for feasible entry deterrence. The discussion above shows clearly that there are situations where irreversible investment expenditures may allow an incumbent to deter entry, but there is an important caveat to bear in mind. Baumol et al. [1982] have argued that fixed costs which give rise to scale economies do not constitute barriers to entry, while sunk costs may. In the Dixit model, for example, the fact that the incumbent cannot recover its capital expenditures, but the entrant can (by not making them), implies that the effective rental rate of capital for the entrant exceeds that of the incumbent. By contrast, fixed costs, which can be completely eliminated in the long run by a total cessation of activity, affect the incumbent and the entrant alike, and can exist in the absence of sunk costs. Baumol et al. give the example of the Monday morning garbage collection in a particular neighbourhood. The average cost per residence (including the costs of getting the indivisible truck and driver to the dump) is higher than the marginal cost of serving an additional residence, and so there are increasing returns to scale. However, they argue that a prospective entrant can adopt hit-and-run tactics without cost disadvantage because the truck and driver can be fully employed in other activities by Monday afternoon: there are no sunk costs. Given that an entrant can enter a given market and then exit costly if and when price retaliation occurs, incumbents cannot block entry of a new competitor who is no more efficient. The potential of hit-and-run entry would constrain price to equal average cost in this market.

This argument is not entirely convincing for several reasons. Scale economies and sunk costs are often closely related. Entry into new markets often involves investment in durable plant and long-term labour and supply contracts, and it is rarely the case that these expenditures can be cancelled with no opportunity cost. Even in the case of trash collection, there are additional costs involved in deploying the truck and driver in a different neighbourhood12 and these would discourage entry. Even very modest sunk costs would be sufficient to deter entry if the competitive response to entry is sufficiently aggressive. The effectiveness of the entry threat described in Baumol et al. relies on the assumption that price would not move quickly relative to the time it takes to enter, earn the profits required to recover any sunk costs, and then leave. If sunk costs are modest, then only a small degree of price rigidity would be necessary to make hit-and-run entry an effective method of market discipline. But there is no assurance that, whatever the level of sunk costs, market prices would be sufficiently rigid to protect a hit-and-run entrant from the rise of an unprofitable entry attempt (see Farrell [1986], Gilbert [1986], and Stiglitz [1987]). Furthermore, whatever the post-entry competition might be, an entrant who anticipates that incumbent firms would act aggressively to maintain market share would deterred from entry if the production technology has increasing returns to scale, regardless of sunk costs. This is the driving principle of the classical BSM model of limit pricing, and Brock and Sheinkman [1981] provide a formalization of the result. They consider the Sylos postulate that quantities would not change after entry and compare the consequences of this assumption to that where potential entrants assume that prices would remain unchanged after entry. Not surprisingly, they find that ‘quantity sustainable’ equilibria do not have the same socially desirable properties that Baumol et al. find for price sustainable equilibria.

The model of limit pricing has attracted criticism not only because of its behaviourial assumptions, but also because it is essentially rather static. Amongst others, Stigler [1968] argued that it may be more desirable to retard the rate of entry rather than to impede entry altogether; Harrod [1952] and Hicks [1954] also pointed to the tradeoff between short run profits and long run losses from entry. Caves and Porter [1977] critized the theory for confining itself to the either/or question of whether a dominant firm will exclude an entrant, and ignoring the more subtle and important issues of the movement into, out of, and among segments of an industry. A related set of problems arises because limit price models focus on competition between insiders and outsiders, neglecting competition between insiders and competition between outsiders. Both types of dynamics consideration and these richer sets of competitive interactions have a major impact on the types of conclusion that are drawn from simple models, and we consider each in turn.

Gilbert and Vives [1986] extend the limit price model of entry prevention to the case of more than one incumbent and a single entrant (the results generalize to more than one potential entrant if entry occurs sequentially—see Vives [1982]). Incumbents act non-cooperatively and each chooses an output taking other firms’ outputs as given.

Entry is prevented if the total industry output exceeds the limit output. For the case of linear demand and constant marginal production costs with a fixed entry fee, they show that entry prevention is excessive in the sense that the industry prevents entry at least as much as, and sometimes more than, a perfectly coordinated cartel would. Moreover, there exist multiple equilibria involving entry prevention, and these can co-exist with an equilibrium in which entry is allowed. When equilibria involving entry prevention and accommodation occur simultaneously, the accommodation equilibrium dominates the equilibrium in which entry is allowed. Entry prevention is a public good, and we therefore expect free riding to occur. Yet, there is no tendency to provide too little entry deterrence in the Gilbert and Vives model. The reason is that each incumbent benefits from entry prevention by an amount proportional to its output and this benefit is independent of the number of incumbent firms. In contrast, the benefit of allowing entry to occur falls with the total number of firms in the industry. Thus with more incumbent firms, non-cooperative behaviour tips the balance in favour of entry prevention relative to what a coordinated cartel would do.

Vives [1982] examines how a single incumbent firm would behave in response to several potential entrants who can choose to enter the market sequentially (as in Prescott and Visscher [1978]). He shows that the incumbent firm will choose either to exclude all of the firms or to allow entry by all of the firms who desire to enter the industry. If the number of potential entrants is at least as large as the number of firms that would enter the industry in the absence of entry preventing behaviour, the incumbent should limit price and deter all entrants (see also Omari and Yarrow [1982] and Gilbert [1986]). If entry is deterred, the market structure is, of course, a monopoly; even if entry is allowed, with the assumed production technology in the Vives model, the market would still be very concentrated.

The limit pricing literature describes the incentives for entry prevention and the conditions that are necessary to maintain a level of output sufficient to deter entry. While the classic BSM model of limit pricing shows conditions under which an established firm would prefer to keep out new competition, Dixit’s [1981] extension of the limit pricing model shows the range of outputs which an established firm can credibly maintain. In other words, entry prevention may be desirable, but not credible. Gilbert [1986] used data on minimum efficient scale and factor costs in 16 industries to investigate conditions under which entry prevention might be credible by a single established firm. Entry prevention is easier the larger is the minimum efficient scale of entry and the larger is the share of costs that are sunk by an established firm. A large share of sunk costs implies that, ceteris paribus, short-run marginal cost when there is excess capacity will be small relative to long-run marginal cost, and this should enable an established firm to maintain a larger output in the face of entry. Gilbert used the share of capital and labour costs as an estimate of sunk costs (the argument for including labour costs is that many labour contracts are difficult to terminate without incurring substantial costs).

Even with the inclusion of labour costs, the share of costs that could be considered as sunk ranged from a low of 23% in petroleum refining to a high of 59% in electric motors. Minimum efficient scale for the 16 industries in the sample varied from about 1% of demand for beer brewing to 23% for turbogenerators. These data allow an estimation of the conditions on demand that would be required to allow a single established firm to maintain an output level large enough to deter entry. From Dixit’s [1981] model, this maximum output sustainable against entry increases with (i) the share of sunk costs (assuming the cost function described by equation (1)), (ii) the minimum efficient scale of entry, and (iii) the elasticity of demand. Knowing (i) and (ii), it is possible to estimate how large the elasticity of demand must be for a single established firm to (credibly) prevent entry. For these industries the elasticity of demand must be at least 1.5 (for cement). The minimum elasticity of demand is typically at least 2.0, and is as high as 4.3 (for petroleum refining). A short-run market elasticity in excess of 2.0 is rather high, and this implies that for most of the industries in this sample, a single established firm would have a difficult time maintaining a large enough output to exclude entry of at least one new competitor. Demand is not sufficiently elastic to make the required entry-preventing output of the established firm, even when the share of costs that are sunk is very large.