At the same moment that we perceive the identity of an object within a frame, we are also aware of the spatial relationship between the object and the frame. These frame ‘fields of forces’ exert pressure on the objects contained within the frame and all adjustment to the composition of a group of visual elements will be arranged with reference to these pressures. Different placement of the subject within the frame’s ‘field of forces’ can therefore induce a perceptual feeling of equilibrium, of motion or of ambiguity.

A field of forces can be plotted, which plots the position of rest or balance (centre and midpoint on the diagonal between corner and centre) and positions of ambiguity(?) where the observer cannot predict the potential motion of the object and therefore an element of perceptual unease is created. Whether the object is passively attracted by centre or edge or whether the object actively moved on its own volition depends on content. The awareness of motion of a static visual element with relation to the frame is an intrinsic part of perception. It is not an intellectual judgement tacked on to the content of an image based on previous experience, but an integral part of perception.

The closed frame compositional technique is structured to keep the attention only on the information that is contained in the shot. The open frame convention allows action to move in and out of the frame and does not disguise the fact that the shot is only a partial viewpoint of a much larger environment (see also page 125).

Frames within frames

The ratio of the longest side of a rectangle to the shortest side is called the aspect ratio of the image. The aspect ratio of the frame and the relationship of the subject to the edge of frame has a considerable impact on the composition of a shot. Historically, film progressed from the Academy aspect ratio of 1.33:1 (a 4 × 3 rectangle) to a mixture of Cinemascope and widescreen ratios. TV inherited the 4:3 screen size and then, with the advent of digital production and reception, took the opportunity to convert to a TV widescreen ratio of 1.78:1 (a 16 × 9 rectangle).

Film and television programmes usually stay with one aspect ratio for the whole production but often break up the repetition of the same projected shape by creating compositions that involve frames within frames. The simplest device is to frame a shot though a doorway or arch which emphasizes the enclosed view or by using foreground masking, an irregular ‘new’ frame can be created which gives variety to the constant repetition of the screen shape.

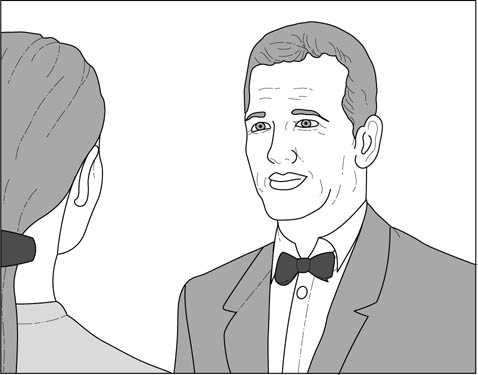

The familiar over-the-shoulder two shot is in effect a frame within a frame image as the back of the foreground head is redundant information and is there to allow greater attention on the speaker and the curve of the head into the shoulder gives a more visually attractive shape to the side of the frame. It has been used in feature film and later television productions since about 1910. Essentially it is a composition that allows the audience to have the same viewpoint as the foreground listener and adds emphasis to the speaker.

There are compositional advantages and disadvantages in using either aspect ratio. Widescreen is good at showing relationships between people and location. Sports coverage benefits from the extra width in following live events. Composing closer shots of faces is usually easier in the 4:3 aspect ratio but as in film, during the transition to widescreen framing during the 1950s, new framing conventions are being developed and old 4:3 compositional conventions that do not work are abandoned. The shared priority in working in any aspect ratio is knowing under what conditions the audience will view the image.