TWO

The Deterioration Trap

How to Manage Market Power to Beat Low-End Competitors

Sometimes research has an accidental quality. I was reminded of this recently when I bought a Louis Vuitton handbag for my daughter. She was very pleased until she took it to school and her classmates made fun of her for buying a knockoff. I knew it was a genuine Louis Vuitton—and had the bill to prove it! But her peers could not tell, and that was actually more important.

The quality of imitators, private labels, and generic products has increased to the point where even discerning eyes—and, believe me, teenage girls are very discerning—have a hard time telling the difference. The handbag episode encouraged me to look further afield. I looked at the discount racks of T.J. Maxx and found Armani suits. I found Burberry at BJ’s Wholesale Club. And these weren’t last year’s fashions. Big-name fashion brand goods can now be found in such stores during the same season they are launched.

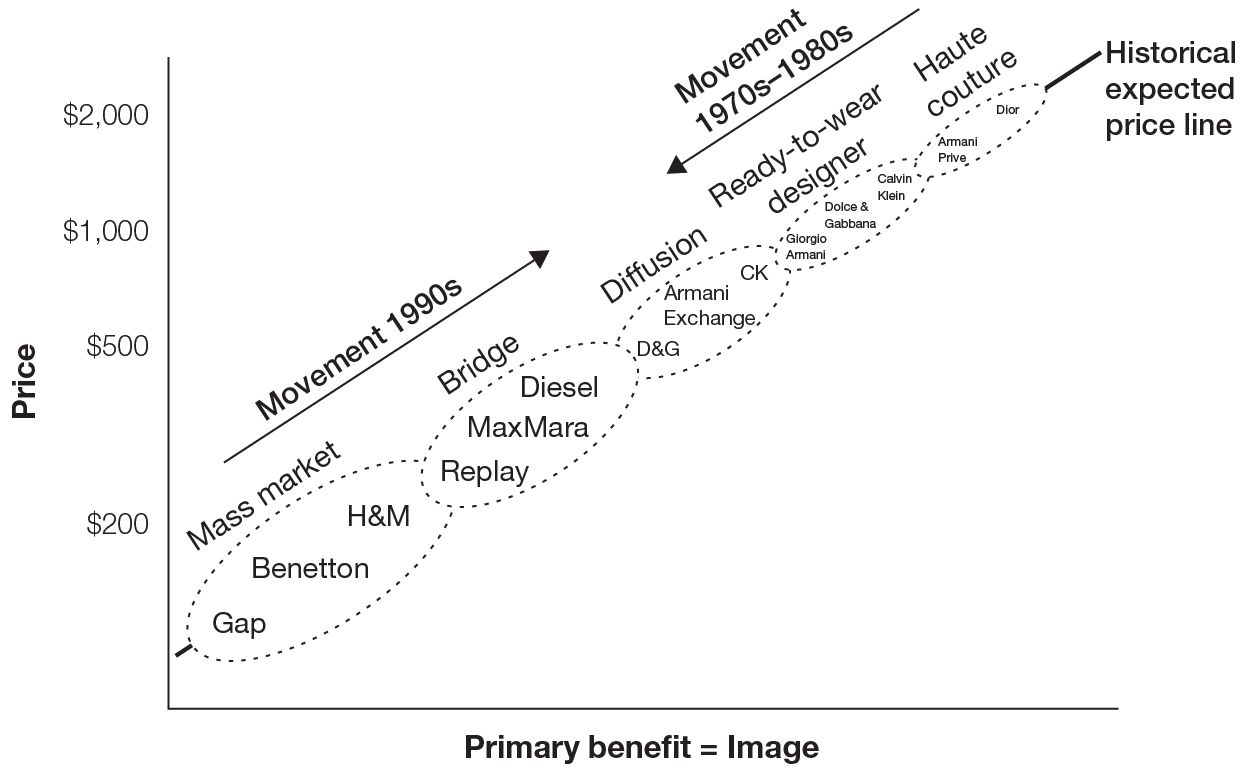

It is a familiar story. The fashion industry once had a clear price-benefit line. Premium designers charged top dollar. Now, the industry is being transformed, and valuable brands find themselves increasingly commoditized.

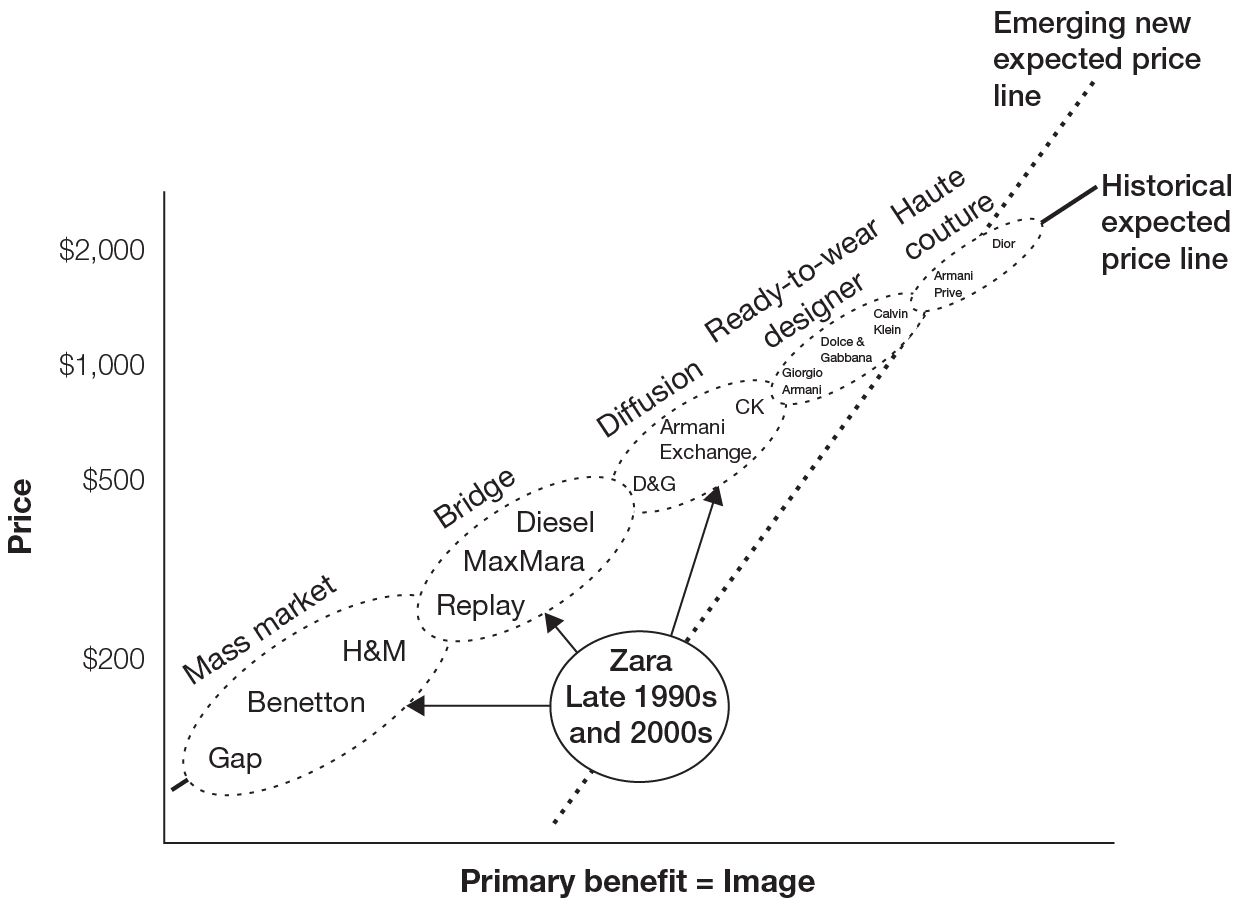

There’s more. Knockoffs and discounting among premium brands are a symptom of broader changes. One of the biggest challenges is emerging at the low end of the European fashion market where the Spanish retailer Zara, owned by Inditex, is using new mass production processes and sourcing strategies to offer low-priced imitations of newly released designer products.1

The emergence of Zara and other fashion-forward discounters is leading to a low-end migration of buyers in the European women’s fashion market.2 This is affecting the entire market. First the lower (mass-market) and mid-price-point segments are affected as direct competitors. But as the middle-price-point brands change their strategies, the ripples have spread to the very top designers, forcing everyone in the industry to shape a response.

Zarafication is not unusual but it is always impressive. It is an exemplar of the first common commodity trap: deterioration (see figure 2-1).

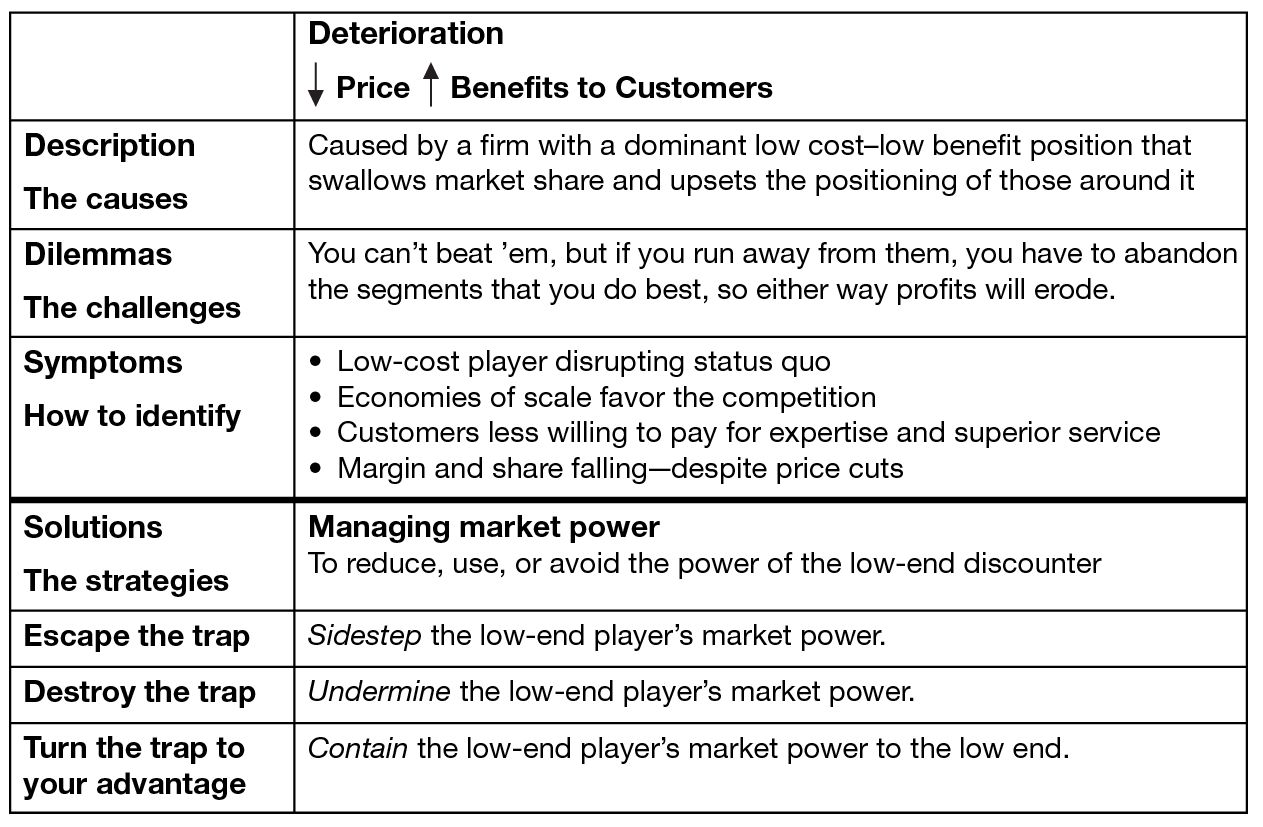

Chapter 2 summary: The deterioration trap

Deterioration occurs when a low-end competitor creates a dominant low price–low benefit position that expands the market share at the low end. Deterioration is created by declining price and lowering (or consistently low) positioning on the product’s primary benefit—the most important benefit offered by products in the industry. Like a black hole, the low-end competitor creates such a dominant price-benefit position that it literally swallows up positions around it. We have seen this pattern with the emergence of value retailers such as Walmart and no-frills airlines such as Southwest or Ryanair. These competitors are such a force to be reckoned with that everyone else has to compete on their terms.

TELLTALE SIGNS

The arrival of a dominant low-end player shakes up the market power of the industry, as Southwest did in the airline industry, Dell once did in computers, or Walmart is still doing in retailing. It is very hard for incumbents to compete with these disruptive players using their existing cost structures. Responses to deterioration must address the shift in market power and manage its distribution across the industry. Firms can do this by adopting market power management strategies that moot, contain, or undermine the market power of the low-end discounters causing the market deterioration. But first they have to recognize what is happening in their market.

So, what are the telltale signs of deterioration? If the following sound familiar, then you are likely to be facing this trap:

- A dominant low-cost competitor has emerged in your market, disrupting the status quo.

- The economies of scale enjoyed by the disrupting company make it impossible for you to compete on price.

- Customers are less and less willing to pay for additional benefits such as superior service and industry expertise.

- Your margins are falling and you are losing market share, even though you have lowered prices and product benefits to catch up with the competition.

The rest of this chapter examines how deterioration occurs and the most effective strategies to combat it.

FASHIONING BRIDGES

To better understand the phenomenon of deterioration, let’s look a little deeper into the fashion industry. What Zara is doing is simply the latest disruptive move in an industry in which business models are constantly being innovated. To fully understand the world of fashion, we need to go back to the 1960s when French and Italian haute couture fashion houses transformed what was a local boutique industry into a global market. Fashion houses typically hand-produced one- or two-of-a-kind products personally designed by a brilliant artist as a special order for wealthy customers. Seeking a broader market, these houses created ready-to-wear fashions, still high-priced but positioned slightly lower than their haute couture lines. Fashion shifted from fine art to an industrial activity—ready-to-wear fashion was usually produced in small batches in job shops. Later, the fashion houses addressed the opportunities created by ready-to-wear for the growing upper-middle market. Haute couture designers rolled up their silk sleeves and created upper-middle price range “diffusion brands” that translated their high-end images to broader markets. Dolce & Gabbana’s D&G; Calvin Klein’s CK; Giorgio Armani’s Emporio Armani and Armani Exchange; Versace’s Versus; and Prada’s Miu Miu were launched to capture different upper-middle market segments.

At the same time, as illustrated by figure 2-2, by the early 1990s, some mass marketers were moving up to the lower-middle price range market. Sweden’s H&M and Italy’s Benetton extended some of their lines to push a number of their products up. Retailers such as Replay and Diesel emerged in Europe using “bridge” brands, which were characterized by brand names with distinctive and fashionable images but not attached to a specific designer. The brand, not the designer, was the identity of the company. And their products were produced in large numbers.

The development of the European women’s fashion industry

And then came fast fashion. Zara, which opened its first store in La Coruña, Spain, in 1975, used superior production technologies and supply chain management to imitate ready to wear fashion. Zara’s model threatened the mass, bridge, and diffusion brands by offering better quality and style but at lower prices. Zara was able to do this by creating a time-compressed production process that has become the subject of many business school case studies. Zara stores—and there are now over thirteen hundred in seventy-two countries—receive two deliveries a week. Each delivery includes new models, so what the stores offer is constantly changing. With over two hundred designers of its own, Zara identifies the trends of haute couture and ready-to-wear, then moves these fashions to the middle market in about four weeks, compared with the six months needed by old technology and processes.

Imitation within four weeks threw the bridge and diffusion brands off their stride. Previously, the fashion firms issued fall and spring collections; but when Zara had imitations available in mid-season, these firms were forced to issue new mid-season designs to differentiate themselves from Zara, leaving them with more excess inventory mid-season. Consequently, they were forced to dump this inventory on discount channels. In the past, buyers got last season’s designs in the discount channels, but now they buy current-season designs at lower prices than the bridge and diffusion brand producers originally intended to charge. This further eroded their image at a time when they needed to distinguish themselves from Zara. Figure 2-3 shows the effect of Zara’s pressure on the market.

Consumer responses to these trends also have brought different parts of the market into closer competition. In Trading Up, Michael Silverstein and Neil Fiske note that consumers are accessorizing low-priced items such as Zara pants with a high-quality (diffusion-level) top or jewelry from a high-end designer.3 The mass and luxury markets are more and more in competition with each other as fashion trends allow more freedom to mix and match, not just on colors and style, but also among prestige levels.

Zara puts pressure on other segments in the women’s fashion industry in Europe by shifting the line

Zara has experienced tremendous growth and rising market power. By 2007, it was the biggest fashion company in Europe, outpacing H&M as the queen of cheap chic. With annual sales of €6,264 million (2007), it is committed to continuing international expansion. In 2008, Korea, Ukraine, Montenegro, Egypt, and Honduras were conquered, and, in 2009, Zara announced a joint venture with Tata Group to open stores in India starting in 2010.

MORE TO COME

Research by McKinsey shows that as long ago as 2002, bargain value retailers already accounted for more than 21 percent of the U.S. apparel market.4 This trend would only increase in this and other markets. There are going to be companies like Zara emerging in a host of other industries. Global competition, the advent of new business models, new manufacturing processes, and the rise of offshoring continue to create opportunities for low-end competitors to appear and take over markets. Half the population of consumers in the United States and Europe shops at value retailers such as Walmart (up from a quarter in 1996).5 Many other industries are experiencing a “shift to value”—something that will be exacerbated by the recent global downturn, But this started long before the downturn, and will continue even in better times.

For example, Geico—the funky name for the Berkshire Hathaway–owned Government Employees Insurance Company—is busy swallowing up the insurance market, based on a low-price promise and clever marketing in which characters from cavemen to geckos offer reminders about how easy it is to use the company’s online services and how to remember its unusual name. Geico has eroded and undermined the positions of traditional competitors, destroying their pricing power and differentiation, leading to commoditization in the auto insurance industry. Geico is now the fastest-growing major U.S. auto insurer, with 8.5 million policyholders.

Rubbermaid once was the dominant domestic player in the plastic goods market, offering surprisingly high-quality, durable products—from doghouses to garden sheds to kitchen storage containers to children’s toys. It earned Fortune’s Most Admired Company award a few years running in the mid-1990s. But Rubbermaid sold through Walmart, which had realized that Chinese manufacturers could make unbranded plastic goods far more cheaply than Rubbermaid could. Rubbermaid’s position deteriorated until it was bought by Newell. Similarly, when Corel and Corningware plates and dishes were hurt by cheaper Chinese rivals, Corning spun off its consumer products group, which ultimately went bankrupt.

The dilemma for managers is that they cannot compete head-to-head with these competitors and hope to win, yet if they stand still they will certainly lose share. Imitation of the imitator is not an option, and escape seems nearly impossible. Movement away from the low-end rival tends to back firms into smaller and smaller niches, while movement toward the rival (imitating and benchmarking it) leads to a no win game. Often a firm can’t match its low-end rival’s economies of scale, cost structure, and experience curve, so it loses the race. Even if it could match its rival’s position, doing so would only serve to accelerate the deterioration when the low end discounter uses its muscle to punish all challengers.

STRATEGIES FOR RESPONDING TO DETERIORATION

How can companies respond to deterioration? What should you do if the entire market is moving toward the low end? The answer comes from the problem: as low end discounters gain market power, their rivals must reduce or manage the market power of the dominant discounter by sidestepping, undermining, or containing or controlling the discounters.

Escape the Trap: Sidestep the Discounter

In a battle with a dominant low-end discounter, sometimes discretion is the better part of valor. Some companies can shift their positions to sidestep the market power of the low-end discounter by making its power irrelevant or by avoiding its power. There are several ways to accommodate or move out of the way of a firm gaining massive market power by low-end discounting. These include moving upscale, moving away, and moving on.

Move Upscale

The first way to sidestep the market power of a firm that’s driving market deterioration is to move upscale, conceding the low-end position to the discounter. For instance, some fashion firms have conceded the low and mid segments of the market and are moving upscale or away from the parts of the market where Zara has the most market power. In this way, the haute couture and ready-to-wear companies hope to perform a neat sidestep by moving into other high-end areas to keep their exclusivity. Some companies, such as Hermès, avoided the low-end threat by focusing entirely on high-end luxury goods that are classics rather than seasonal or annual fashion statements. Hermès reduced the number of its licensees and the stores carrying its goods to increase its exclusivity. Diesel and Chanel pursued a similar strategy.

Others are choosing unique materials to sidestep Zara, such as Diesel’s focus on building expertise and dominance in denim products. Some high-end brands are also using rare fibers such as “baby cashmere,” which comes from the first combing of a young goat, requiring about twenty goats to make a single sweater. This is a place where mass-producing low-end players cannot follow.

When the demand for luxury goods remains solid, thanks to the stability of the distribution of wealth among the rich, staying focused on this target segment can keep high-end brands out of Zara’s reach. Brands using this strategy emphasize exclusivity to clearly separate themselves from the low end. In some rare instances, the move can be so successful that it actually reverses the deterioration by drawing the market upscale away from the discounter.

The silk industry in Italy—responsible for over 90 percent of European silk production—successfully competed against low-cost Chinese rivals by concentrating on high-value-added positions. As a result, during one period of eight months, exports of Italian silk to China increased by 155 percent, despite the availability of low-cost silk from China.

Part of the secret of success in Italian silk making has been several initiatives to move upscale and redefine benefits for customers. Small Italian silk makers in the northern Italian city of Como, for example, joined together to create a new brand that gave them the scale and marketing to compete more effectively in global markets. These companies also co-invested in new technologies to produce higher-quality fabrics that don’t tear, irritate skin, or stain. They are changing how quality is defined for certain segments of the market, allowing them to effectively meet the Chinese challenge. The Italian manufacturers were also able to add convenience, innovation, and flexibility to their services. This allowed them, at least in the short term, to utilize the sidestep strategy—moving away from the pull of the market power of low-end players. Instead of trying to beat the low-end rivals—a competition that Italian silk makers were ill prepared for—they moved up out of the line of fire.

Move Away

Unless moving upscale is movement into a large or growth segment, moving upscale may not be enough. If so, companies can also move away from direct competition with the low-end player by changing channels, time, or place. For example, Procter & Gamble’s Iams brand and Hill’s Pet Nutrition’s Science Diet were initially sold through vets and specialty pet stores to avoid competition with large competitors such as Purina in the supermarkets. While coffee brands such as Folgers were fighting bitter price wars in the supermarkets for what had been seen as a commodity product, Howard Schultz created Starbucks as an entirely new channel for brewed coffees and beans, breaking free of commoditization until Starbucks over-saturated the market with too many stores.

End runs can also be achieved by moving to new geographies. When Southwest came into the domestic airline market, major carriers focused more attention on international routes where Southwest was not a problem. While the low-end players are using less-well-known brand names, the same pattern of accommodation can be seen in oral care products. While Colgate and P&G share the market in the United States, Colgate is the dominant player in many places overseas, enjoying more than a 70 percent share in many foreign countries. Under Reuben Mark’s leadership, Colgate divested itself of many unrelated business units and refocused on its core—oral care products. The company staked a solid claim in the global toothpaste market and proved many times that it would react aggressively if competitors tried to infiltrate its international strongholds. It is interesting to note that, while Colgate doesn’t promote its noncore brands aggressively overseas or in the United States, the firm continues to retain these brands as toehold positions just in case the competition decides to move into its strongholds. Colgate has accommodated P&G and other rivals in the American domestic market but chosen to fight its battles abroad. By moving away, Colgate has enjoyed a long record of strong, stable, steady growth in earnings per share and an incredibly impressive appreciation in its stock price until the 2008 credit crunch.

Move On

Many haute couture companies are sidestepping Zara’s market power by moving out of fashion clothing to avoid the deterioration there, instead investing more of their attention on other very high-end products. They are designing everything from designer hotels and restaurants (Armani, Bulgari, Versace, and others); consumer electronics and appliances (Armani is working with Samsung); cell phones (Prada is in partnership with LG); automobiles (Versace is designing the interiors of Lamborghinis); helicopters (Armani and Versace are designing the interiors of helicopters created by AgustaWestland); furniture (Armani Casa); and even floral arrangements at branded florist shops (Armani Fiori). Armani, in particular, is attempting to create a unique lifestyle and customer experience called the “Armani Lifestyle.” It is an appeal to the very wealthy, using products so high end and unique that they do not compete with Zara, nor can they be imitated by Zara’s mass production and sourcing system.

Sometimes companies exit from the market of a low-end competitor completely. When Asian companies began taking over the memory chip industry, Intel realized it could not compete on price so it shifted to making microprocessor chips for personal computers. When it faced newly competitive followers in microprocessors such as AMD during the late 1990s and cheap Asian microprocessors in the early 2000s, Intel moved to making chips for consumer electronics and other special applications.

When he took the helm as CEO in the mid-2000s, Paul Otellini realized that Intel needed to look beyond personal computers to growth markets, such as consumer electronics and health care, to escape the commodity trap of low-end players. He created the first new slogan for the company in many years: “Leap ahead.” The leap was spearheaded with Intel’s Viiv chip for consumer electronics (with the potential to draw together the home PC, TiVo, stereo, and cable television). Alliances with Cisco in networking and Motorola in wireless communications were established. Chips for digital medical systems for hospitals and remote health monitoring at home were developed. Intel also introduced its dual core chips into Apple computers for the first time, and was developing chips for devices from BlackBerrys to iPods. To prime the company to launch more products than ever before in its history, Intel hired twenty thousand new employees, including a bevy of anthropologists to shake up the engineering firm (one output from the anthropologists is Intel’s Technology Metabolism Index, which charts technology adoption). In the face of overwhelming deterioration in its core market, Intel appeared to be preparing to escape to new products or new markets. In February 2009, the company unveiled plans to invest $7 billion in U.S. factories that will make new, 32-nanometer chips and support seven thousand high-tech jobs.

Another approach to moving on is to redefine your target segment and create products with primary benefits that fit that segment, as appears to have happened in the increasingly commoditized chewing-gum business. When Wrigley’s traditional brands were imitated and underpriced, or sold alongside a lot of discounted candy, Wrigley saw its market share shrink. So Wrigley moved on to a new set of hot sugar-free brands, such as Orbit, which was differentiated based on innovation and functional attributes such as breath freshening, teeth whitening, or serving as a low-calorie snack.6

By mid-2007, traditional gums were losing market share, with Doublemint declining 5 percent over the year before, JuicyFruit down 19 percent, and Bubblicious and Bubble Yum off 21 percent and 11 percent, respectively. On the other hand, the popularity of the new sugar-free gums grew. Sales of Orbit, the market leader, had rocketed ahead 23 percent, Trident Splash grew by 103 percent, and Cadbury Adams’s Stride expanded by more than 1,000 percent.

To keep ahead of this new game and help to shape the new primary benefit, Wrigley launched a $45 million Global Innovation Center in Chicago in 2005. Among its next-generation creations, it developed a high-concept offering called “5” that promises to “stimulate your senses.” So the move to sidestep the fierce competition in the traditional segment actually led to a new growth segment that is replacing the traditional segment.

Destroy the Trap: Undermine the Discounter

The second way to beat a commodity trap is to attack it. Probably the hardest but also the most rewarding way to destroy a deterioration trap is to undermine the market power of the low-end discounter.

One way to undermine a competitor is to erode its power from below by offering even lower prices and benefits through a reinvented value chain that still generates profits. Another strategy is to redefine the way customers see price. Say a company is taking share by selling a very inexpensive product, such as an almost “disposable” car with very low product durability and easily replaceable engines and other parts to extend its life. The perceived purchase price of these cars could be increased, and the market share of the firm decreased, if rivals convince customers to look at the total cost of ownership, including repair and replacement costs, over the long term. So the perceived price of the product is redefined to include more than the initial purchase price.

Redefine Value

Companies can undermine the discounter by staking out a new position that is even lower or by fighting to neutralize the advantage of the discounter. Even if a new low-end competitor is moving in, there are many ways to create positions that undermine the rise of the entrant by attacking its low-cost or quality position. This can be done through simplified design, the stripping out of product benefits, or a reinvented value chain that lowers costs. Alternatively, a company can challenge the value proposition of the low-end rival.

In the fashion industry, for example, some companies are using celebrities and advertising to raise their image and directly undermine the value proposition of discount players. European mass retailer H&M is trying to neutralize Zara’s model of designerless fast fashion imitations by offering low-priced products while using stars such as Madonna and guest designers such as Karl Lagerfeld, Stella McCartney, and Roberto Cavalli to raise its image. The goal is to undermine Zara by offering more for a lower or similar price. In addition, H&M is redesigning its store formats to look more attractive than Zara’s stores in Europe. H&M displays its clothing on shiny steel racks, which look more upscale than the boxes and bins through which many European Zara customers have to search.

Fashion-forward players such as Gucci and Dior use innovation and speed to undermine or match Zara’s advantage in imitation, making half their sales from new products each year, compared with about 20 percent on average for less-fashion-forward firms. By rapidly introducing products and repositioning brands to have clearer positions and better-defined customer segments, customers are buying the intangible brand image, uniqueness, and emotional content of Gucci and Dior products, making Zara’s emphasis on imitating the physical product less effective.

These firms are not running away from Zara. They are making themselves fast enough to partially neutralize Zara’s advantage by making imitation more difficult. They now issue eight collections per year rather than two, as they once did. Gucci Groupe (owned by French conglomerate PPR) is repositioning its collection of brands (Gucci, YSL, Bottega Veneta, Alexander McQueen, Stella McCartney, and Balenciaga) to get more consistency and to clarify each brand’s image and target market.

Armani and other major designers like Dolce & Gabbana now preview portions of their collections in private showings to manufacturers and retailers. As a result, they sell most of their designs in secret well before they hit the runway, preempting Zara’s imitation of their designs after they become publicly released. Some 60 to 70 percent of Armani revenues are attributable to such “pre-collection” sales.

Another potential way to undermine Zara’s value proposition is through selling used clothing. While high-fashion houses are fighting for new clothing, there has been a rapid expansion of the market for used clothing. In the United States, the small, unorganized stores in this sector are being replaced with more organized chains. For example, “pre-owned” designer clothing chain Buffalo Exchange, with thirty-four stores nationally, did $56 million in revenue in 2008. Is this the CarMax of the clothing industry? Is there an opportunity for the high-end brands to create their own “pre-owned” fashion business in Europe, as Toyota did with certified pre-owned Lexus cars?

For example, in many cases haute couture and ready-to-wear garments have been worn only once before being discarded by their wealthy buyers, so there is room to create used-clothing stores that are not vintage stores. A designer could offer trade-in credits for used clothing toward the purchase of another used item or even a new high-end dress. And since there is no wear and tear to speak of, customers can purchase a relatively recent dress at a low price. This would undermine discounters such as Zara.

Automation can obviously change the cost structure of an industry. But the surprise is that even service industries are being automated and industrialized with outsourcing, off shoring, software, and new operational processes.7 Take the car-repair business. The vast majority of car repairs and bodywork was typically done in small, dirty, mom-and-pop shops that offered work of dubious quality, using pirated parts for a discounted price. Countering these low-end discounters were the high-priced car dealers that used genuine factory parts, all the latest diagnostic tools, and highly trained technicians; but many customers avoided them, fearing that these shops’ real purpose was to convince consumers that they needed to buy a new car. Now, specialty chains have emerged that use automation to industrialize their service, undermining the low-end providers by charging less than the independents while offering a more professional image, faster turnaround, better service, and higher customer satisfaction.8 Assembly-line procedures have been employed in both repair and bodywork by specialist firms. Thus, even when faced with a low-end competitor, companies sometimes have opportunities to undermine them by staking out an even lower position.

Redefine Price

Another way to undermine the market power of a low-end discounter is to redefine price. The key to a low-end discounter’s market power is its price, which drives market share. As it continues to drive down prices, the discounter destroys rivals and increases it scale, further lowering its costs. One way to undermine this power is to change customer perceptions of pricing. For example, frequent flier miles in airlines helped to offset the low prices of no-frills competitors by bundling the price of the ticket with future free travel.

There are many opportunities to switch the way customers see prices during a purchase decision without redefining the primary benefit or having to strip off secondary benefits. By focusing on the total cost of ownership (including energy, financing, repairs, downtime, and other operating expenses) rather than just the initial purchase price, GE has fought off lower-priced rivals in numerous businesses during the 2000s, including the locomotive and large turbine markets. GE bundles financing, repair services, and other services into the purchase price, making the total life-cycle cost of its products lower than its rivals’.

Companies can also give away the product or sell it at a very low price, then make their money on recurring revenues. Adobe gives away Acrobat Reader for its popular PDF format, but charges for software to create Acrobat files. Companies also can give away the product and charge a usage fee as is done with products from copiers (based on copies made) to leased automobiles (based on miles driven). Companies also charge for results. Consulting firms and other service organizations are now charging not by the hour or the project, but for the performance improvements that they deliver to their clients.

Another way to change pricing is to charge a membership fee but keep product prices low; warehouse clubs such as BJ’s and Costco do this. Sometimes companies use complexity in a way that makes it hard for customers to compare pricing, as with cell phone plans, medical insurance, or airline tickets. (Of course, this creates opportunities for another redefinition of prices based on simplified pricing.) These are just a few of the ways that pricing moves can be used to contain the market power of a low-end discounter.

Turn the Trap to your Advantage: Contain and Control the Discounter

The third way to beat a deterioration trap is to turn it to your advantage. In this strategy, companies work to contain the market power of the discounter to a limited part of the market.

Contain by Surrounding

The power of the low-end discounter can be contained by establishing positions around it—in effect creating a proliferation trap, as discussed in chapter 3. Consider what was happening to Walmart before the recession.

Target drew away some of Walmart’s market share by emphasizing design and style over price alone. Meanwhile, Costco and BJ’s Wholesale Club changed pricing to undermine Walmart’s market power, using membership fees to consistently offer merchandise at lower prices than Walmart superstores. The clubs focused on a limited selection of high-volume items that allowed them to sell the most popular trip-generating products for less.

Krogers, the largest independent grocery chain in the United States, also had success in challenging Walmart’s entry into the grocery business. Using slightly lower prices and improved customer service, Krogers continued to grow in the face of a threat from more than one hundred Walmart Superstores.9 Kroger’s has a “Customer 1st” strategy which, it says, focuses on four things: “Our people are great!; I get the products I want, plus a little; the shopping experience makes me want to return; and our prices are good.”10 Using this strategy, Krogers increased market share in thirty-seven of its fortyfour major markets in 2007 and recorded sales of $70,235 million, up 6 percent.

In essence, Walmart’s rivals used a proliferation trap to contain for several years the deterioration trap Walmart had created. But since deterioration in the market was rejuvenated by the recession that started in 2008, Walmart once again gained the upper hand. As people’s incomes shrink, they no longer seek proliferation, returning instead to the basics offered by low-end discounters.

Nevertheless, a swarm of rivals, particularly small ones, can turn the inflexibility and weight of the large company against it. For example, when clothing discounters like T.J. Maxx and the wholesale clubs pushed into the low-end clothing markets, Walmart began to try to compete in fashion. But it was fighting with a disadvantage. Walmart had trouble stocking stores with the right sizes for its customers because its customers typically wear much larger sizes than those made by fashion houses sold at the wholesale clubs and T.J. Maxx.

As rivals buzz around its ears, avenues for the expansion of the low-end discounter can be blocked. As specialists surrounded it, Walmart’s growth slowed during the mid 2000s. Due to its already large number of sku’s, Walmart was unable to expand its assortment to match the specialists without increasing inventory costs and the costs of increased complexity in its purchasing and distribution functions.

Microsoft has staved off containment by specialists by bundling numerous applications, such as Microsoft Office, browsers, and security software into its operating systems. In security software, Microsoft’s bundling strategy poses a tremendous threat to stand-alone software makers such as Symantec and McAfee. By offering security products such as firewalls and antivirus programs for free, Microsoft makes it impossible for rivals to compete on price.11 This type of deterioration is tough to beat, as companies such as Lotus and Netscape discovered. But many companies have beaten “free” by containing it at the low end of the market; examples include bottled water versus tap water, and private health care providers versus free government health care providers (for example, the Veteran’s Administration).

Intuit, for instance, beat back Microsoft by using speed to contain Microsoft Money in accounting products by offering more responsive customer service and the ability to keep up with fast-changing tax and accounting rules. Symantec and McAfee are responding by adding features that Microsoft doesn’t offer. McAfee is adding software that provides improved security management for computer systems administrators who want to establish and enforce policies about the degree of protection and access to various machines, types of data, and software. While Microsoft is protecting the operating system, Symantec is protecting information, and in the future might offer more protection in other areas such as interactions and identity.

Of course, Microsoft could imitate these moves but not so easily as you might think. Both accounting/tax and security software requires expertise and frequent and timely updating that is difficult for a behemoth like Microsoft to provide. These constraints help to contain and block Microsoft’s market power from some parts of the software market.

Companies can also use a geographic brand of containment. D&G is expanding the number of its company-owned boutiques around the world to compete better against companies such as Zara. By taking back control from licensees, D&G hopes to be able to execute its strategies against the discounter more quickly and forcefully. Benetton expanded its network of fifty-five hundred stores and increased its fashion cycles to four per year while reworking its image through advertising and new store design to try to contain the threat of Zara to the low end. At the same time, H&M is also beginning to contain Zara to its customer niche by introducing a series of specialized stores targeting different segments, such as children’s clothing, accessories, and lingerie, to surround Zara.

Some diffusion brands, such as Roberto Cavalli’s Just Cavalli and Gianfranco Ferre’s GF Ferre, are reducing their prices to contain Zara as well. At the same time, Chloé offered lower prices through its new See brand.

Legal maneuvering is another strategy for containment. Chloé, for example, is defending its diffusion designs against imitators using lawsuits, such as the one filed against UK-based Topshop (the UK chain was forced to destroy over one thousand of its dresses that copied a £185 Chloé design) and another against Kookaï for selling copycat versions of its snakeskin Silverado handbags.

Control by Moving Customers in the Market

A low-end discounter can also be controlled by moving customers to an upscale value proposition. This is more than moving the firm upscale—not only does the firm move its products upmarket, but it also redefines the market by taking its customer base with it, leaving the discounter with a shrinking market niche. As mentioned earlier, sometimes the sidestep move—if supported with clever repositioning and innovation—can be so successful that companies find a way to draw the entire market upward, essentially reversing the deterioration caused by the low-end competitor. In essence, the company moves upscale to escape the trap and in doing so migrates customers to the upper end of the market. This is a difficult strategy to implement, but when possible it avoids the danger of allowing the low-end discounter to grab more market share and power, forcing powerless non-discounters to become trapped in the gilded cage of a high-end niche. Instead of merely moving upscale and leaving much of the market behind with the low-end discounter, firms using this strategy take the market with them by offering a high-end product at a price below the expected price line.

This approach was successfully used by Gillette in meeting the challenge of the low-end entry of BIC disposable razors. The disposables took away share from Gillette’s higher-priced cartridge razors, which offered more benefit (closer shave) at a higher price. Gillette first responded by matching the move at the low end with its own disposable Good News razor, launched in 1976. But margins were so tight that, even though Gillette was successful in gaining share, this move contributed to the deterioration trap that BIC had created. Gillette’s profits deteriorated, and its success in disposables became a pyrrhic victory: Gillette narrowly avoided a hostile takeover in the 1980s.

Instead of continuing to fight it out in the brutally price-sensitive low-end, Gillette turned to raising the bar at the high end, starting with the Sensor. It offered such a compelling price-benefit position that Gillette actually took market share away from the disposables, deteriorating BIC’s position from above. From this new starting point, Gillette then went on to drive the process of escalation (as described in chapter 4), managing the momentum with a series of launches, including the Sensor, Mach3, and the Fusion models. Gillette always had its next-generation product waiting in the wings, and had at least one extension product to anticipate the moves of followers—for example, the Sensor Excel, the Mach3 Turbo, and M3Power. Its innovations have raised the bar on safety, smoothness, and closeness of shaving. Yet with Fusion, it appears that Gillette may be running out of room to keep driving the momentum, because how much closeness is too close? So Gillette had to look for a new way to change the game. By selling the company to P&G, Gillette can now tap into many new distribution strategies to gain market share, making new product development a less important feature of its strategy. But overall, what started out looking like an effort to make moot the low-end discounter’s market power by moving upscale, ultimately contained and even reduced BIC’s market power over the long run.

In some cases, deterioration becomes too hard to handle and there is no way to escape, destroy, or take advantage of it. This is especially true when deterioration is caused by a protracted economic downturn or other factors that evaporate a significant amount of demand. Under such circumstances, other strategies must be employed to survive (see “Deterioration and Demand Evaporation”).

Deterioration and Demand Evaporation

A sharp economic downturn sometimes causes the perfect storm. Market prices and benefits deteriorate as customers feeling the pinch seek bargains—and demand simply evaporates. While technically not commoditization, this type of deterioration makes it particularly difficult for firms to improve their competitive position or pricing power by escaping, undermining, or using the deterioration. In such situations, additional measures must be taken to survive the hurricane, including:

- Batten down the hatches to weather the storm by protecting the firm’s core business. This includes measures such as getting back to basics by pruning low-profit products and geographies or segments, decreasing discretionary spending, cutting excess capacity to prop up prices, reducing costs (through layoffs, more efficient processes, restructuring, and other such measures), and doing only the essentials necessary to survive. The goal is to maximize cash flow from core operations. Aggressive management of the top line is required as well. Customers must be convinced that the firm’s products are a basic necessity to compete with rivals, or will solve or prevent a major problem that the company might face in the future. The sales force may be directed to bypass purchasing agents to discuss sales with higher-level executives. Products or processes may be imported from emerging markets into the core business to capture emerging market knowledge about low-cost processes and low-end products. Firms will typically keep prices low, but not start or exacerbate price wars.

- Prepare to float with the hurricane winds to absorb or avoid too much financial and strategic damage. This is done by being proactive and moving before the problem worsens. To make it easier to absorb financial losses, firms lower their breakeven points by reducing debt-to-equity ratios, refinancing debt, reducing dividends and stock buybacks, and cutting fixed costs and assets, replacing them with variable costs or outsourcing. Firms unlock cash from their operations by cutting inventory and capital expenditures, stretching payables, and collecting receivables sooner. They often increase their strategic and operational flexibility and adjust their portfolios more quickly. Firms also reevaluate their risks from operations and their credit policies. The goal is to bite the bullet early in one large chunk rather than to suffer incremental loses as the firm makes reactionary incremental moves to adjust to increasing losses and declining demand.

- Landing on your feet when the storm is over. The best firms don’t just react to the storm. They position for the future by selectively increasing their R&D during the storm to be ahead of competitors when the storm breaks. Some firms look for transformative mergers as rivals weaken during the shakeout, creating opportunities to consolidate or reduce capacity in key markets. Others improve customer service, or even invest in customers, relying on the idea that customers will remember the favor when the inevitable recovery comes. Still others use the crisis to reinvent their business models and position for pent-up demand and the growth markets that will emerge after the downturn.

They work with the government to create new regulations designed to prevent future downturns, but simultaneously raise barriers to entry for post-downturn potential entrants. And they anticipate the inflation that might occur when the government prints money to pay off recession-era government debts incurred by stimulus and bailout packages, or the impact on the working, middle and upper classes when taxes are increased and other benefits cut to help balance the budget.

I think it was put best by Winston Churchill, who once said: “If you are going through hell, just keep on going!”

FIGHT OR FLIGHT? YOU CHOOSE

The key decision about market power management strategies is whether to fight or flee. Like any schoolyard fight-or-flight decision, the choice is based on the relative strengths of your rivals (whether you think you can win the fight) and the opportunities for flight (if there is an escape route). Winning the fight depends on the resources you have to throw at the battle relative to the low-end competitor. If you are hopelessly outmatched, then the choice may be to flee if a sidestepping move is feasible. If you are evenly matched or have an advantage, then containing or undermining the discounter becomes more possible. It is not just your own resources that count, but also the resources of partners that you can pull into the fray. As Zara has gained market power in fashion, using its profits to expand rapidly, it has been harder for rivals to stop Zara, or even to keep up. Fear of retaliation may also affect whether rivals choose to confront or contain the low-end player. In brief, companies caught in the deterioration trap need to assess the balance of power between themselves and the low-end discounter.

If you can’t win the fight with the low-end player, then the question is whether there is a route out. Can you aid someone else’s effort to undermine the low-end discounter or find an ally to help, as IBM did to Dell by selling its PC division to low-cost Chinese manufacturer Lenovo? If you already have a high-end brand or product position, you must judge whether your position will be a safe haven or will be affected by the ripples made by the low-end discounter, as we saw in the fashion industry. If there are ripple effects, your position is tenuous, but it can still be used as a launch platform for moving away or moving on to avoid the deterioration caused by the discounter. The question is whether you can move on or away quickly enough before your market share in your old position is so depleted so that you lack the resources to make the move. If your brand is focused on a smaller niche or a safe haven, then the issue is whether you can find a way to expand the market for this brand. If there is no path out, then you might be forced to come up with a way to fight—even though you will be in an unfair fight with a behemoth. In many cases, industry consolidation, or an extensive network of alliance partners, may be needed to gain the critical mass required to fight the low-end discounter.

Finally, you must consider the costs and risks of flight. If you have a valuable brand, sidestepping may stop deterioration temporarily, but at the sacrifice of your long-term brand equity. Flight may also signal weakness to the competitor and lead it to pursue you more aggressively up the price-benefit line or in other markets, as Toyota did to GM by starting with small cars and moving up to SUVs, luxury cars, and recently into larger light trucks. So flight may just lead to another tougher fight in the future. All these factors will affect the choice of a strategy to battle deterioration.

While Zara offers much lower quality and prestige than its haute couture rivals, the market power of a dominant low-end player more than makes up for its downsides. This change can be seen in the rising fortunes of Zara’s owner Amancio Ortega. With a net worth of $24 billion, he was Spain’s richest man and number 8 on the 2007 Forbes global list of billionaires. The son of a railway worker, he got his start making gowns and lingerie in his living room more than four decades before founding Zara in 1975. His fortune places him ahead of Stefan Persson (17), the head of the H&M chain started by his father, and far in front of Giorgio Armani (177) and the Benettons (323). There is a lot of money to be found at the low end of the market.

Fighting the market power of a large and growing low-end discounter that is causing the entire market to deteriorate can make you feel like David fighting Goliath. Yet Napoleon Bonaparte’s words remind us that “the essence of strategy is, with a weaker force, always to have more force at the crucial point than the enemy.” And if we recognize a rising power, we can undermine or contain it before it can gather too much market power. One wonders why Sears did not imitate or buy discounter Home Depot before it ruined Sears’s home improvement business. Or why one of the large retailers did not imitate or buy discounter Walmart before it gathered steam. As Leonardo da Vinci observed: “It is easier to resist at the beginning than at the end.”