C H A P T E R 7

Getting Everything Up and Running

This chapter guides you through setting up all the essential components of your Ubuntu installation. This includes hardware configuration, as well as setting up e-mail. It covers the post-installation steps necessary to get your system up and running efficiently.

Like all modern Linux distributions, Ubuntu is practically automated when it comes to setting up key hardware and software components. Key software will work from the start, and most hardware will be automatically configured. However, you might need to tweak a few settings to make everything work correctly. Read on to learn more.

Will Ubuntu Support My Hardware?

The age-old criticism that the Linux OS lags way behind Windows in terms of hardware support is long dead. The majority of connectable devices, such as digital cameras and printers, will work with Ubuntu immediately, with little, if any, configuration.

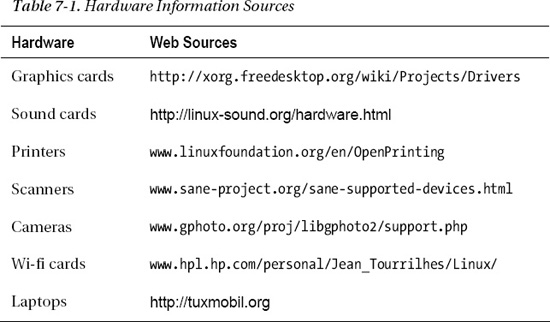

Most underlying PC hardware is pre-configured during installation without your knowledge and without requiring further work, so with luck there will be less hunting around for drivers than you might be used to with Windows. Your graphics and sound cards should work without a hitch, for example. In addition, nearly all USB and FireWire devices you plug in after installation will be supported. (Table 7-1 lists some online sources of information about hardware support for Ubuntu). You'll be surprised at how many user manuals now have a section for Linux—often given equal weight to Mac OS. Documentation for Netgear routers is one example.

However, it's still the case that a substantial number of devices are not supported by Ubuntu. Generally, it's a black or white situation: Ubuntu either works with a piece of hardware or it doesn't.

The types of hardware that Ubuntu doesn't support are often esoteric devices that rely on custom software provided by the hardware manufacturer, but even in mass-market areas such as printers, scanners, and wireless adapters, some manufacturers are still frustratingly uninterested in publishing their own Linux drivers, and even refuse to provide details about the hardware to volunteer programmers who offer to write free and open source drivers at no expense to the company. It's also sometimes the case that brand-new models of hardware won't work with Ubuntu when they first hit the market. Companies prioritize developer resources, so Windows drivers generally get written before Linux drivers. However, as soon as a new piece of hardware comes out, work is usually undertaken to ensure that Linux is made compatible with it, by the company, the community, or a combination of the two. This is especially true of hardware such as printers and scanners, and it's one more reason why you should regularly update your system online.

![]() Tip Before you hit the stores to buy a new piece of hardware, it's a good idea to do a little research. Compatibility with Linux is sometimes listed on the hardware box or at the manufacturer's web site (even if you sometimes need to search through the FAQ section to find out about it). And, of course, others may have tried your particular small object of desire, so searching <hardware name> + Linux compatibility in Google may provide enlightenment. Another good source for information on Ubuntu hardware compatibility, is www.ubuntu.com/certification.

Tip Before you hit the stores to buy a new piece of hardware, it's a good idea to do a little research. Compatibility with Linux is sometimes listed on the hardware box or at the manufacturer's web site (even if you sometimes need to search through the FAQ section to find out about it). And, of course, others may have tried your particular small object of desire, so searching <hardware name> + Linux compatibility in Google may provide enlightenment. Another good source for information on Ubuntu hardware compatibility, is www.ubuntu.com/certification.

Unfortunately, unlike with Windows, it's not very common to find Linux drivers on the CD that comes with the hardware. Even if you do find a Linux driver supplied, chances are that it will work with only certain enterprise-oriented versions of Linux, such as Red Hat Enterprise Linux or SUSE Linux Enterprise Desktop. Some drivers are usable but imperfect or lack features that are available in their Windows counterparts. At the time of this writing, Ubuntu has yet to gain the kind of momentum that leads manufacturers to specifically produce drivers for it, but this may change in the future, especially as more users encounter the system via Netbooks and mobile devices. Various OEMs have dipped their toes in the open source water. Dell and Shuttle are the biggest names currently bundling Linux with some of their desktop offerings, with smaller specialist companies like System 76 competing with excellent pre-installed offerings.

At the other end, Linux takes care of addressing most hardware through the kernel. If the hardware manufacturer has made specifications for a device available to the public, there probably is an open source driver available in the kernel to address your hardware. This is especially true for hardware devices that are a bit longer on the market (which means that open source developers have had time to develop specific drivers. If that is the case, you'll see that Ubuntu just recognizes the device and no additional configuration is needed at all.

![]() Note It's possible to use a program called alien to convert software installation packages designed for other distributions into Ubuntu installation files. Doing so isn't complicated but may not work well with driver files because of the subtle differences in where system files are stored across different Linux distributions. You can find more information about alien at

Note It's possible to use a program called alien to convert software installation packages designed for other distributions into Ubuntu installation files. Doing so isn't complicated but may not work well with driver files because of the subtle differences in where system files are stored across different Linux distributions. You can find more information about alien at http://kitenet.net/~joey/code/alien/. It's contained within the Ubuntu software repositories and can be downloaded using the Ubuntu Software Center or Synaptic Package Manager. A graphical front end to alien is available at http://code.google.com/p/foxoman/wiki/PackageConverter.

Using Proprietary vs. Open Source Drivers

As discussed earlier in this book, Linux is an open source OS. This means that the source code underlying Linux programs is available, so that everyone who is interested can contribute to its further development, or study the way the software was written. This is a good thing when it comes to hardware drivers, because bugs in the code can be spotted and repaired by anyone with an interest in doing so. If you consider that a bug in a graphics driver could mean your PC crashes every 5 minutes, the value of such an approach is abundantly clear.

Unfortunately, some hardware manufacturers don't like to disclose how their hardware works, because they want to protect their trade secrets. This makes it impossible for them to release open source drivers, because such drivers would expose exactly how the hardware operates. Because such companies are aware that growing numbers of people use Linux, they release proprietary drivers, whose source code is not made publicly available (in the same way that Windows source code is not released to the public).

Aside from ethical issues surrounding not being able to study the source code, the biggest issue with proprietary drivers relates to bug fixing. To use a proprietary driver is to be at the mercy of the hardware manufacturer's own development and release schedule. If the driver has a serious bug, you'll either have to work around it or put up with troubling issues until the manufacturer offers an update. A few years ago, a proprietary driver for a 3D graphics card stopped any computer it was installed on from going into hibernation mode (that is, suspending to disk). Those using the drivers had to wait months until the fix was released.

Despite this, and although the folks behind Ubuntu strongly support free and open source software, they realize proprietary drivers need to be used in certain situations. For example, it's impossible to use the 3D graphics elements of some graphics cards unless you have a proprietary driver, and this means that visual effects will be unavailable to users who happen to have hardware that isn't currently fully supported by open source drivers.

Because of this, Ubuntu automatically installs wi-fi proprietary drivers by default if no open source alternative exists (or if the open source version is not yet good enough). It also offers the opportunity to easily install some proprietary graphics card drivers if they provide more functionality than the open source versions.

![]() Note Linux sees hardware in a technical way, rather than in the way humans do. If you attach something such as a USB CD-R/RW drive, Linux will recognize the drive hardware and attempt to make it work. It won't try to find a driver for that specific make and model of CD-R/RW drive. Thus, Linux is able to work with a wide range of hardware, because a lot of hardware is similar on a technical level, despite the differences in case design, model names, and even prices!

Note Linux sees hardware in a technical way, rather than in the way humans do. If you attach something such as a USB CD-R/RW drive, Linux will recognize the drive hardware and attempt to make it work. It won't try to find a driver for that specific make and model of CD-R/RW drive. Thus, Linux is able to work with a wide range of hardware, because a lot of hardware is similar on a technical level, despite the differences in case design, model names, and even prices!

WHAT HARDWARE WORKS?

Installing Device Manager

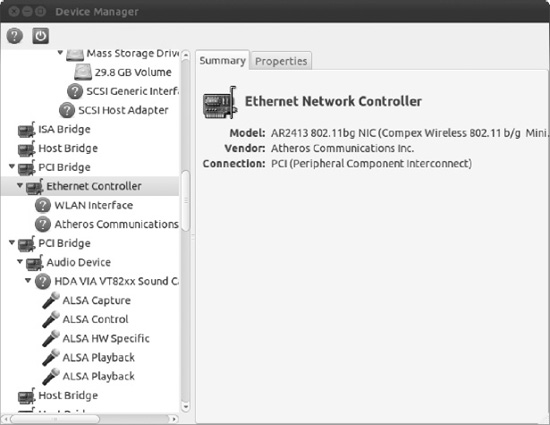

When using Windows, you might have come across Device Manager, the handy tool that lists your PC's hardware and provides access to various properties. Ubuntu offers a similar piece of software, as shown in Figure 7-1, but it isn't installed by default.

After you can connect to the Internet (following the instructions in the “Getting Online” section of this chapter), you can install Device Manager by using the Synaptic Package Manager (see the “Installing Software” section of this chapter), as follows:

- From the panel, select the Ubuntu Software Center icon and click it.

- Your cursor is automatically in the search field, so go ahead and type

device manager. - A list of programs will appear. Click Device Manager and then click the Install button that appears. Enter your password when asked.

- A progress bar will show that the software is installing. When it's done, a green tick will appear by the program's icon. You can now close the Ubuntu Software Center window.

Figure 7-1. Ubuntu's Device Manager program can display just about everything you need to know about attached hardware.

After you've installed Device Manager, you can open it from the Ubuntu menu by typing Device Manager in the Search bar. Next click the icon to launch the program. You'll need to click View ![]() Device Properties to ensure that Device Manager adds the useful (but occasionally overwhelming) Properties tab.

Device Properties to ensure that Device Manager adds the useful (but occasionally overwhelming) Properties tab.

You should be aware of a few important differences between the Windows and Ubuntu versions of Device Manager. Though the aim of Ubuntu's Device Manager is to manage hardware devices, the project is still in its infancy and can provide only hardware information at the time of this writing. On the other hand, Ubuntu's list is far more comprehensive than that in Windows. In Ubuntu, Device Manager thoroughly probes the hardware to discover its capabilities.

Perhaps the biggest difference, however, is that just because a piece of hardware is listed within Ubuntu's Device Manager doesn't mean that the hardware is configured to work with Ubuntu. In fact, it doesn't even imply that the hardware will ever work under Ubuntu. Device Manager's list is simply the result of probing devices attached to the various system buses (PCI, AGP, USB, and so on) and reporting the data.

Nonetheless, Device Manager is the best starting place if you find that a certain piece of hardware isn't working. If a piece of hardware is listed, then it proves, if nothing else, that the system recognizes that the hardware is attached. For example, later in this chapter, we describe how you can use Device Manager to discover crucial details about wireless network devices, which you can then use to install drivers.

![]() Tip If your computer is not yet online, you'll need to use a computer that is online (perhaps another computer, or Windows if you dual-boot) to download the software, and then copy it across to your Ubuntu computer for installation. To download the software, visit the following two addresses in your browser. You will be prompted to download a file after typing each address:

Tip If your computer is not yet online, you'll need to use a computer that is online (perhaps another computer, or Windows if you dual-boot) to download the software, and then copy it across to your Ubuntu computer for installation. To download the software, visit the following two addresses in your browser. You will be prompted to download a file after typing each address:

http://us.archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu/pool/universe/g/gnome-device-manager/gnome-device![]()

-manager_0.2-3_i386.deb

http://us.archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu/pool/universe/g/gnome-device-manager/libgnome![]()

-device-manager0_0.2-3_i386.deb

After the files are downloaded, copy them to the Desktop on your Ubuntu machine, using a USB memory stick or similar storage device. Right-click the icon for libgnome-device-manager0_0.2-3_i386.deb and select the first choice in the context menu, Open With Gdebi Package Manager. A Package Installer window will appear. Click the Install Package button and supply your password when asked. Close the window when the package has finished installing. Next, right-click the other icon, for gnome-device-manager itself and repeat the same procedure.

Configuring Ubuntu

Unlike some versions of Linux, Ubuntu doesn't rely on a centralized configuration software package. Instead, it uses smaller programs to configure hardware. For example, to configure the network, you'll use the NetworkManager program, and printers are configured using a separate printer configuration program. Because using some of the configuration software involves reconfiguring your entire system, doing so requires administrator privileges. Therefore, you'll be prompted for your login password each time you use some of the programs. In some cases, after you've made changes, you'll need to click the Apply button to put the changes into effect. When you've finished configuration, simply close the program window by clicking the Close button.

![]() Note Ubuntu remembers your password for 5 minutes after you enter it. Therefore, if you open the same application or another that requires administrator privileges within that amount of time, you won't be prompted to enter your password again.

Note Ubuntu remembers your password for 5 minutes after you enter it. Therefore, if you open the same application or another that requires administrator privileges within that amount of time, you won't be prompted to enter your password again.

GETTING HELP FROM THE COMMUNITY

Configuring Input Devices

Mouse and key repeat speeds are personal to each user, and you may find the default Ubuntu settings not to your taste, particularly if you have a high-resolution mouse such as a gaming model. Fortunately, changing each setting is easy.

Configuring Mouse Options

Open Applications and in the search bar, type mouse to display the Mouse Preferences icon. Click it to open the Mouse Preferences dialog box, which has General and Accessibility tabs. On a laptop, you might also see the Touchpad tab.

General Mouse Settings

On the General tab of the Mouse Preferences dialog box, shown in Figure 7-2, you can configure several options.

Figure 7-2. The Mouse Preferences dialog box lets you tame that mouse.

These options are as follows:

- Mouse Orientation: This option lets you set whether the mouse is to be used by a left-handed or right-handed person. Effectively, it swaps the functions of the right and left buttons.

- Locate Pointer: This option allows you to show where the mouse is by displaying a ripple surrounding the mouse pointer when you press the Ctrl key. This can be useful for partially sighted people who may not be able to locate the cursor on a busy Desktop.

- Acceleration: This setting controls how fast the mouse pointer moves. Whenever you move the mouse, the pointer on the screen moves a corresponding amount. However, the cursor actually increases in speed the more you move your hand (otherwise, you would need to drag your hand across the desk to get from one side of the screen to the other). This is referred to as acceleration. If you set the acceleration too high, the pointer will fly around the screen, seemingly unable to stop. If you set it too slow, you'll need to swipe the mouse several times to make it go anywhere.

- Sensitivity: This setting controls how quickly the acceleration kicks in when you first move the mouse. Choosing a higher setting means that you can move the mouse relatively quickly before it starts to accelerate and cover more screen space. A low setting means that acceleration will begin almost as soon as you move the mouse. Higher sensitivity settings give you more control over the mouse, which can be useful if you use image-editing programs, for example.

- Drag and Drop: This setting determines the amount of mouse movement allowed in a dragging maneuver before the item under the cursor is moved. It is designed for people who have limited dexterity and who might be unable to keep the mouse perfectly still when selecting an item. In such cases, a large threshold value may be preferred.

- Double-Click Timeout: This is ideal for those who are less physically dexterous, because the double-click speed can be slowed down. On the other hand, if you find yourself accidentally double-clicking items, you can speed it up. Test your settings by double-clicking the lightbulb image.

Changes are made as each setting is adjusted, so to test the new settings, simply move your mouse.

Accessibility Settings

The settings on the Accessibility tab can help people with physical disabilities use the mouse. However, to enable these features, you need to enable Assistive Technologies in Ubuntu first, as follows:

- Open the Assistive Technologies Preferences dialog box (from the panel, click Applications and type assist in the search bar. This will show the Assistive Technologies icon. Click it to open the Assistive Technologies preferences.

- Select the Enable Assistive Technologies check box and then click the Close and Log Out button (this is necessary to start the background services).

- Select Log Out in the Shutdown dialog box, and then log back in again when prompted.

- After logging in, return to the Accessibility tab of the Mouse Preferences dialog box (Applications

Mouse).

Mouse).

From the Accessibility tab, you can enable Simulated Secondary Click and dwell click options. Selecting the “Trigger secondary click by holding down the primary button” check box simulates a right-click after you hold the left-click for a certain amount of time (useful for those having trouble right-clicking). The right-click actually occurs when you release the mouse button, for instance bringing up a context menu if you're clicking on a file icon. The amount of time you have to hold down the mouse button can be configured by moving the Delay slider to the left for a faster response or to the right for a longer delay.

A dwell click allows you to simulate a mouse-click action after the mouse pointer has been left idle for a certain amount of the time so, for instance, hovering over an icon for a few seconds could double-click it to launch an application. To enable this feature, select “Initiate click when stopping pointer movement.” You can set the length of the idle time by moving the Delay slider to the left for less idle time or to the right for a longer delay. The Motion Threshold setting determines the amount of pointer movement allowed while the mouse is still considered idle (useful for those who might be unable to control small movements of their hands). Moving the Motion Threshold slider to the left makes the mouse pointer sensitive; moving it to the right makes the pointer less sensitive. You can choose two types of dwell click:

- Choose type of click beforehand: This option automatically clicks the mouse when the mouse pointer is idle. If you want to choose the type of mouse click each time, put a check in the box beside Show Click Type Window. This will show a floating window, from which you can select various types of clicks, such as single-click, double-click, and so on. Alternatively, you can choose the mouse click from the Dwell Click applet instead. (Applets are discussed in the “Working with Applets” section later in this chapter.)

- Choose type of click with mouse gestures: This option allows you to choose the type of mouse click to execute when the mouse movement is idle by moving the mouse in a certain direction, usually up, down, left, or right. Just wait until the mouse turns into a cross and then move the mouse. After you've performed the movement, the mouse will return to its original location before it was moved. All the mouse movements can be customized by changing the gestures in the drop-down lists for Single Click, Double Click, Drag Click, and Secondary Click.

![]() Note Orca, GNOME's screen reader software, also includes a tool that magnifies the area under the mouse pointer. It is available in the Assistive Technologies Preferences. Select the Preferred Applications option and set Orca to “run at start.” The software can be used to both magnify an area of the screen under the mouse and, using a speech synthesizer, read onscreen elements out loud.

Note Orca, GNOME's screen reader software, also includes a tool that magnifies the area under the mouse pointer. It is available in the Assistive Technologies Preferences. Select the Preferred Applications option and set Orca to “run at start.” The software can be used to both magnify an area of the screen under the mouse and, using a speech synthesizer, read onscreen elements out loud.

Touchpad Settings

The Touchpad tab in the Mouse Preferences appears on laptops only. You can set the following options:

- Disable touchpad while typing: It's easy to brush against the touchpad accidentally with the ball of your thumb while you're typing. This option, which is enabled by default, eliminates the problem by disabling the touchpad momentarily after each keypress.

- Enable mouse clicks with touchpad: This allows you to simulate a mouse click by tapping the touchpad. Depending on the sensitivity of your touchpad, this is either great or the most annoying thing in the world.

- Scrolling options: Like a scroll wheel on a mouse, your laptop's touchpad can be used to scroll pages and images up and down, or even left and right. By default, vertical edge scrolling is enabled, so that running your finger up and down the right edge of the touchpad will scroll web pages up and down. If you enable horizontal scrolling, you will additionally be able to scroll left and right by running your finger along the bottom edge of the touchpad. The two-finger scrolling option disables edge scrolling, and instead makes the touchpad scroll if you have two fingers moving on it at the same time. If you don't like any of these features, you can choose to disable scrolling completely.

Changing Keyboard Settings

From the applications interface, type keyboard. This shows the Keyboard icon which you can use to open the Keyboard Preferences dialog box. This dialog box has five tabs: General, Layouts, Accessibility, Mouse Keys, and Typing Break.

General Settings

The General tab offers Repeat Keys settings and a Cursor Blinking slider. You can alter the rate of key repeat, which can be useful if you often find yourself holding down the Backspace key to delete a sentence; a shorter setting on the Delay slider and a faster setting on the Speed slider can help. However, if you make the delay too short for your typing style, you may find double characters creeping into your documents; typing an f may result in ff, for example.

Modifying the Cursor Blinking slider setting may help if you sometimes lose the cursor in a document. A faster speed will mean that the cursor spends less time being invisible between flashes.

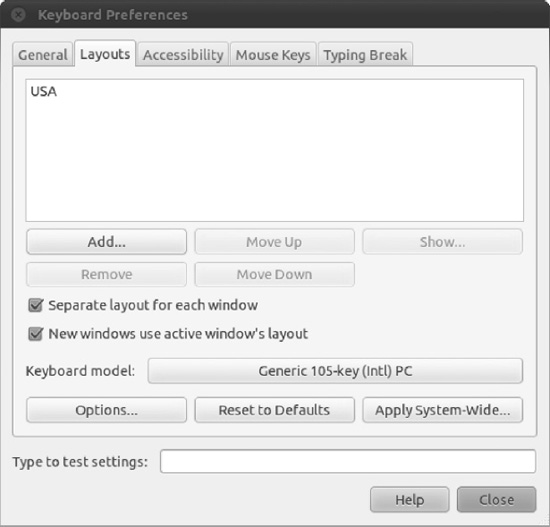

Layouts Settings

On the Layouts tab, you can choose your keyboard model, add an alternative keyboard layout, and configure layout options, as shown in Figure 7-3. Typically, the generic keyboard works fine for most setups. However, if you want to make full use of the extra keys on your keyboard, such as Mail, Web, Power, Sleep, Suspend, and so on, you should select your keyboard model.

If you write in two different languages on your keyboard, it may be helpful to be able to switch between them. Click the Add button, and select the second language from the list. To switch from one language to another, you can add the Keyboard Indicator applet in a panel and toggle from one language to another by clicking the applet.

The Keyboard Layout Options dialog box, accessed by clicking the Options button, lets you select from a multitude of handy tweaks that affect how the keyboard works. For example, you can configure the Caps Lock key to act like a simple Shift key, or you can turn it off altogether. You can configure the Windows key so that it performs a different function too. Put a check alongside the options you want after reading through the extensive list.

Figure 7-3. You can select another keyboard layout at this place

Accessibility Settings

As with the mouse, there are also accessibility options for keyboard users to help people with physical disabilities. On the Accessibility tab, you can configure the following settings:

- General: You have an option to enable/disable (“toggle”) accessibility features with keyboard shortcuts. This is disabled by default.

![]() Caution Do not check the box labeled “Accessibility features can be toggled with keyboard shortcuts” unless you are sure you need it. Once enabled, if you happen to hold down the Shift key for eight seconds, or tap the Shift key five times, a dialog window will appear asking whether you want to enable the Sticky or Slow Keys features. This can be a source of confusion!

Caution Do not check the box labeled “Accessibility features can be toggled with keyboard shortcuts” unless you are sure you need it. Once enabled, if you happen to hold down the Shift key for eight seconds, or tap the Shift key five times, a dialog window will appear asking whether you want to enable the Sticky or Slow Keys features. This can be a source of confusion!

- Sticky keys: Some people are unable to hold down more than one key at a time, which is a problem if you want to type a keyboard shortcut such as Ctrl+S to save your work. As its name suggests, the sticky keys feature “holds down” keys such as Shift, Ctrl, and Alt while you press another key on the keyboard. To enable sticky keys, select the Simulate Simultaneous Keypresses check box. You can test sticky keys by running the File Browser (click Files and Folders from the panel). Try pressing Alt and F sequentially; Nautilus will open the File menu as if you pressed those keys simultaneously. If you would like to disable sticky keys on the fly, without having to use this dialog box, select “Disable sticky keys if two keys are pressed together.” You can test this by pressing Ctrl+Alt. A Sticky Keys Alert dialog box will appear to prompt you to disable sticky keys.

- Slow keys: This feature controls the reaction rate of keys. By moving the Delay slider to the left, the reaction rate of the keys becomes faster. By moving the slider to the right, the reaction rate of the keys becomes slower, to the point that you would need to hold the key for a certain amount of time for it to be considered as a key press. This has obvious uses for people with limited dexterity in their fingers, but most people will not want this enabled.

- Bounce keys: This feature controls the repetition of letters on the screen when the same key is accidentally pressed. By moving the slider to the left, the repeat rate will be quicker; moving it to the right adds time for the key to be repeated.

At the bottom of the dialog box is a text box for typing to test the settings you've just configured. You can also enable sound notifications by clicking the Notifications button. These notifications will let you know when the keyboard accessibility features have been enabled or disabled. You can set sound alerts for accessibility in general, sticky keys, slow keys, and bounce keys.

Mouse Keys Settings

The mouse keys feature lets you use your numeric keypad to control the mouse pointer. By selecting the “Pointer can be controlled using the keypad” check box and pressing the Num Lock key, you can move the mouse pointer by typing from the numeric keypad.

With mouse keys enabled, the 5 key both simulates a mouse click and acts as the center of a directional wheel surrounding it. The 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9 keys simulate mouse direction. Some numeric keypads have arrows on them to indicate this.

You can move the Acceleration slider to adjust the time it takes while pressing the mouse keys for the mouse movement to reach full speed.

The Speed slider sets the distance offset of the mouse pointer when you press a mouse key. By moving the Speed slider left, the mouse pointer covers a smaller distance when you press a mouse key, giving you the illusion that the mouse movement is slower. By moving the Speed slider right, the mouse pointer covers a larger distance when you press a mouse key, giving you the illusion that the mouse movement is faster.

The Delay slider determines the amount of time to press the mouse keys before the mouse pointer starts to move. You can set the delay by moving the Delay slider to the left for a quicker response time and to the right for a longer delay.

Typing Break Settings

The Typing Break tab features a function that can force you to stop typing after a predetermined number of minutes, to give your fingers and wrists a rest. It does this by blanking the screen and displaying a “Take a break!” message. Note that a notification area icon will appear before the break time to give you advanced warning of the lockout.

Creating Keyboard Shortcuts

Ubuntu lets you define your own keyboard shortcuts for just about any action on the system. To create a shortcut, from the Panel, open Applications and type keyboard. This shows a few icons, including the Keyboard Shortcuts icon. Click it andin the dialog box, search through the list for the action you want to create a shortcut for, click it, and then press the key combination you want to use. For example, you might locate the Volume Up and Volume Down entries in the list, click each, and press Ctrl+left arrow and Ctrl+right arrow. Then you will be able to turn the volume of your sound card up or down by holding down Ctrl and tapping the left or right arrow key, respectively.

![]() Caution Be careful not to assign a shortcut to a popular key. It might be nice to make Totem media player appear when you hit the spacebar, for example, but that will mean that it will start up several times whenever you type a sentence in a word processor! Also be aware that some key combinations are used by applications. Within OpenOffice.org's Writer, for example, the Ctrl+left/right arrow key combination moves you from word to word in a paragraph. If you define those combinations as shortcuts, you will no longer have this functionality.

Caution Be careful not to assign a shortcut to a popular key. It might be nice to make Totem media player appear when you hit the spacebar, for example, but that will mean that it will start up several times whenever you type a sentence in a word processor! Also be aware that some key combinations are used by applications. Within OpenOffice.org's Writer, for example, the Ctrl+left/right arrow key combination moves you from word to word in a paragraph. If you define those combinations as shortcuts, you will no longer have this functionality.

An example of a handy shortcut is to configure your Home folder to appear whenever you press Ctrl+Home. This can be done by locating the Home Folder option under the Desktop heading.

Getting Online

Getting online is vital in our modern Internet age, and Ubuntu caters to all the standard ways of doing so. Linux was built from the ground up to be an online operating system and is of course based on UNIX, which pioneered the concept of networking computers together to share data back in the 1970s. However, none of this is to say that getting online with Ubuntu is difficult! In fact, it's easy.

Regardless of whether you use a mobile broadband connection, a standard wired Ethernet network device or a wireless network device, the same program, NetworkManager, is used to configure your network settings under Ubuntu. Support for many makes and models of equipment is built in, so in most cases, all you need to do is enter a few configuration details.

![]() Note Linux runs about 60 percent of the computers that make the Internet work! If you use Google, Facebook, or Wikipedia, you're using Linux. As your Linux skills increase, you'll eventually get to a stage where you, too, can run your own Internet servers. It sounds difficult but can be quite easy.

Note Linux runs about 60 percent of the computers that make the Internet work! If you use Google, Facebook, or Wikipedia, you're using Linux. As your Linux skills increase, you'll eventually get to a stage where you, too, can run your own Internet servers. It sounds difficult but can be quite easy.

Using NetworkManager

NetworkManager lets users easily manage wireless (also known as wi-fi) and wired connections, as well as mobile broadband connections. An icon for this utility sits in the notification area at the top right of the Desktop and changes according to the type of connection currently active (up/down arrows for wired network, radio waves for wireless network, and so on). NetworkManager automatically detects any wireless networks that are in range, as well as if you're currently plugged in to a wired network. If you automatically connect to a network, a black notification box will appear on the top right of your screen for a few seconds and then fade away.

Clicking the NetworkManager icon in the upper right corner of the screen will show a list of networks detected. By selecting an entry in the list, you can then connect to the network, and you'll be prompted to configure WEP/WPA protection, if applicable.

![]() Caution At times we have been prompted for the wrong kind of wireless protection—for example, we were asked for a 128-bit WEP key rather than a 64-bit key when trying to connect to a network. In other words, it pays to check that you're being prompted for the right thing, and to select the correct option if you're not. Failure to do so might result in frustration! If you are really stuck, make sure to read your wireless router documentation.

Caution At times we have been prompted for the wrong kind of wireless protection—for example, we were asked for a 128-bit WEP key rather than a 64-bit key when trying to connect to a network. In other words, it pays to check that you're being prompted for the right thing, and to select the correct option if you're not. Failure to do so might result in frustration! If you are really stuck, make sure to read your wireless router documentation.

Following this, the NetworkManager icon will display the signal strength of the connection for as long as you're connected. By clicking it, you'll be able to see at a glance what network you're connected to and any others within range. If you want to switch networks, just click the NetworkManager icon and select a different network in the list. If it's a secure network, you'll be prompted for a password before you're granted access.

![]() Tip By right-clicking the NetworkManager icon, you can opt to completely disable your network hardware if you wish. This is quite useful if you don't need a network and would like to conserve your laptop battery.

Tip By right-clicking the NetworkManager icon, you can opt to completely disable your network hardware if you wish. This is quite useful if you don't need a network and would like to conserve your laptop battery.

NetworkManager settings persist across reboots, provided the network that was last configured is in range. This means that NetworkManager is ideal for all kinds of wireless network users, from those who frequently switch between different networks (that is, mobile workers) to those who just use a single wireless network connection, such as that provided by a wireless network broadband router in a home/small office environment. NetworkManager will also let you switch to a wired (Ethernet) connection, if and when you attach one to your computer.

NetworkManager will automatically detect networks and the type of connection. If you want to manually supply details, such as the IP address and gateway, or the name of the wireless base station—which might be necessary if your base station doesn't broadcast its name or if you need to connect to a specialized setup—you can do so by editing the connection.

Configuring Wired Networking

Every conventional desktop or laptop computer comes with an Ethernet port which is used to make a wired network connection to a router, hub, or switch.

Wireless networking as an alternative is extremely popular, particularly of course for portable devices such as laptops, but connecting via a cable offers advantages in speed, reliability and security. For these reasons wired Ethernet connections are still the standard in office environments. Even at home, if you have a desktop computer located close to your router, you may as well connect them using the Ethernet cable that came with your router.

In most cases, NetworkManager will sense a wired Ethernet connection and automatically connect using the Dynamic Host Control Protocol (DHCP). This means that your computer receives its IP address, gateway, subnet mask, and Domain Name System (DNS) addresses automatically. All routers manufactured today are set up to automatically use DHCP out of the box.

![]() Tip If a DHCP server is not available, Ubuntu will attempt to set up a network automatically using the Zeroconf (or Zero Configuration Networking) system, just like Microsoft Windows systems. (Microsoft refers to this as Automatic Private IP Addressing, but it's also known as link-local.) In other words, if a bunch of computers plug into a hub or router on an ad hoc basis, without being configured and without a DHCP server operating, they will be able to network with each other. To make this work, each computer randomly assigns itself a unique IP address that starts with

Tip If a DHCP server is not available, Ubuntu will attempt to set up a network automatically using the Zeroconf (or Zero Configuration Networking) system, just like Microsoft Windows systems. (Microsoft refers to this as Automatic Private IP Addressing, but it's also known as link-local.) In other words, if a bunch of computers plug into a hub or router on an ad hoc basis, without being configured and without a DHCP server operating, they will be able to network with each other. To make this work, each computer randomly assigns itself a unique IP address that starts with 169.254 with a subnet mask of 255.255.0.0.

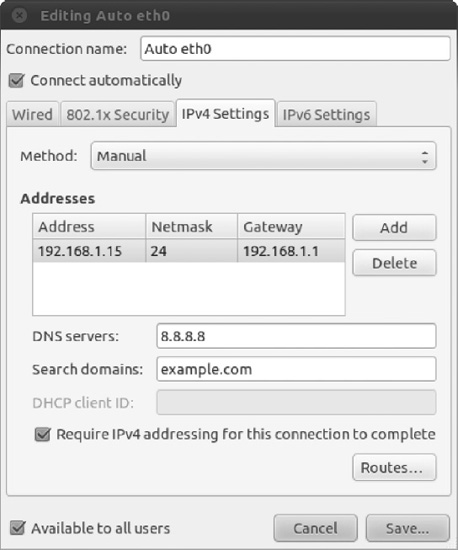

If you need to manually specify network details such as IP and router addresses, perhaps because you work in an office environment with nonstandard systems, start by speaking to your system administrator or technical support person to determine the settings you need. Ask the administrator for your IP address, DNS server addresses (there are usually two or three of these), your subnet mask, and the router address (sometimes called the gateway address). The settings you will get from your system administrator will usually be in the form of a series of four numbers separated by dots, something like 192.168.0.233. After you have this information, follow these steps:

- Left-click the NetworkManager icon in the notification area and select Edit Connections from the menu.

- Select the Wired tab from the tab bar and click the Add button. This launches the new network configuration screen, where you can create a profile for the wired network. To change settings of an existing wired connection, select the connection which is typically marked as Auto eth0, and click Edit to modify its properties.

- Provide a name for the new connection. Then select the IPv4 Settings tab and change the Method drop-down from Automatic (DHCP) to Manual.

- Click Add and supply the IP address, subnet mask, and gateway address for the device. You should also fill in the areas for DNS Servers and Search Domains. You can add more than one address to these sections by separating each one with a comma. Figure 7-4 shows an example of these settings. Click Apply after filling in the information. The network will be added to the list.

Figure 7-4. Ubuntu will automatically work with DHCP networks, or you can define a static IP address.

![]() Tip If you're using a static IP address with a router, such as that provided by a DSL modem, the DNS address is often the same as the router/gateway address.

Tip If you're using a static IP address with a router, such as that provided by a DSL modem, the DNS address is often the same as the router/gateway address.

Your network connection should now work. If you now have more than one wired network connection set up, you can switch between them by clicking on the NetworkManager icon and selecting the appropriately named connection under Wired Networks. If your newly set up connection isn't working, try rebooting. However, if your system administrator mentioned that a proxy must also be configured, you'll need to follow the instructions in the “Working with a Proxy Server” section later in this chapter.

Connecting to a Wireless Network

A wireless (wi-fi) network is, as its name suggests, a network that does away with cabling and uses radio frequencies to communicate. It's more common for notebooks and handheld computers to use wireless connections, but some desktop computers also do. Indeed, it's increasingly the case that many workplaces are switching to wireless networking, eschewing old-fashioned, cable-based networking.

![]() Note Slowly but surely, wi-fi is replacing wired Ethernet networks. However, sometimes wi-fi networks are impractical or simply undesirable. For example, the metal infrastructure in some buildings means the signal becomes unreliable. Wi-fi is also considered too insecure for some companies, as the wi-fi signal often spreads to the street outside the building. Although such transmissions are nearly always secured and WPA2 is considered secure, wi-fi security implementations have been broken. Ethernet might be considered old technology, but trying to steal data from physical cables is an order of magnitude more difficult, to the point of being practically impossible.

Note Slowly but surely, wi-fi is replacing wired Ethernet networks. However, sometimes wi-fi networks are impractical or simply undesirable. For example, the metal infrastructure in some buildings means the signal becomes unreliable. Wi-fi is also considered too insecure for some companies, as the wi-fi signal often spreads to the street outside the building. Although such transmissions are nearly always secured and WPA2 is considered secure, wi-fi security implementations have been broken. Ethernet might be considered old technology, but trying to steal data from physical cables is an order of magnitude more difficult, to the point of being practically impossible.

Notebooks and PDAs typically use built-in wireless network devices, with an invisible antenna built into the case. However, some older notebooks might use PCMCIA cards, which have an external square antenna, and some desktop computers might use PCI-based wireless cards or USB dongles, which have external rubber/plastic antennas, in the style of old cell phones.

Ubuntu includes support for most wireless network devices. However, it's possible to use Windows wireless network device drivers for unsupported hardware. In the past this was necessary rather often, nowadays you'll find that your wireless network card is supported in most cases. In rare cases, Ubuntu appears to support a wireless network device, in that it identifies it and lets you configure it, but you might find that it simply doesn't work (or works very badly, perhaps with an intermittent connection). In this situation, you can also try installing Windows drivers. See the “Installing Windows Wireless Network Device Drivers” section later in this chapter for details.

![]() Note Ubuntu is rare in the Linux world in that it uses some proprietary (closed source) wireless device drivers by default. Ubuntu is, after all, an open source OS and is committed to the goals of free and open source software. The use of proprietary drivers is considered a necessary evil because not all devices have open source drivers right now, and not all open source drivers support all the functions you might be used to (typically, they might not support the WPA functionality of your wi-fi device, for example). The use of proprietary drivers is regarded as a stopgap measure, and it's hoped that manufacturers will realize that it is in their interests to support open source driver development, making proprietary drivers redundant.

Note Ubuntu is rare in the Linux world in that it uses some proprietary (closed source) wireless device drivers by default. Ubuntu is, after all, an open source OS and is committed to the goals of free and open source software. The use of proprietary drivers is considered a necessary evil because not all devices have open source drivers right now, and not all open source drivers support all the functions you might be used to (typically, they might not support the WPA functionality of your wi-fi device, for example). The use of proprietary drivers is regarded as a stopgap measure, and it's hoped that manufacturers will realize that it is in their interests to support open source driver development, making proprietary drivers redundant.

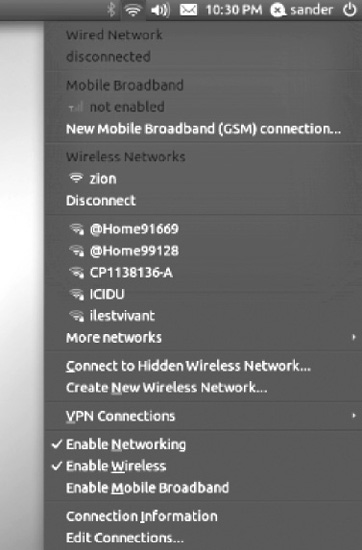

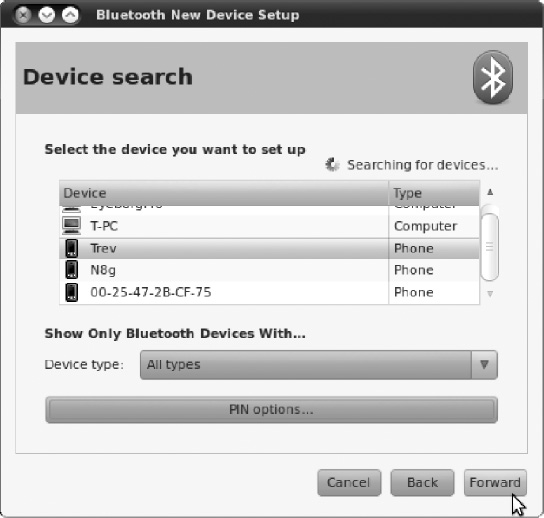

Connecting to a wireless network device is easy with NetworkManager. Just click the NetworkManager icon, and you will see the available wi-fi networks in the Wireless Network list. Networks protected with WEP/WPA have a padlock in the wireless icon to the right of the name, as shown in Figure 7-5. Those that are “open” don't have this padlock.

Figure 7-5. Clicking the network icon displays a list of available wireless networks.

You might see many wi-fi networks listed, depending on your location. The wireless base stations are identified by their Service Set Identifier (SSID) or sometimes ESSID, with E standing for Extended.

If the SSID you would like to connect to is not listed by NetworkManager, it could mean that your wireless base station isn't set to broadcast its SSID or, worse, Ubuntu's wi-fi drivers aren't functioning correctly. If it's the former, all you need to do is right-click the NetworkManager icon and select Connect to Other Wireless Network. Then, in the new dialog box, type the SSID under Network Name, set Wireless Security to None or the appropriate security type, fill in the other information depending on the type of wireless security you selected, and click Connect. If it's the latter, you may need to use a Windows driver, as described in the next section.

![]() Tip If you are not offered any wireless networks at all, ensure that the wireless hardware is switched on. Some notebooks have a keyboard combination to turn it off to save battery power. Others have a little switch located on one of the edges of the notebook. Left-click the NetworkManager icon and ensure that Enable Networking and Enable Wireless are both selected.

Tip If you are not offered any wireless networks at all, ensure that the wireless hardware is switched on. Some notebooks have a keyboard combination to turn it off to save battery power. Others have a little switch located on one of the edges of the notebook. Left-click the NetworkManager icon and ensure that Enable Networking and Enable Wireless are both selected.

To connect to a wi-fi network, select the wireless base station you want to connect to in the list. If it isn't protected by WEP/WPA, you will be connected to it automatically.

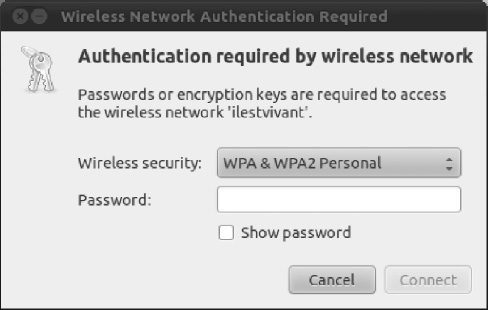

If the wi-fi network you wish to connect to is protected with WEP or WPA, a dialog box will appear, prompting you for the password/passphrase, as shown in Figure 7-6. In the Wireless Security field, make sure the correct type of security for the wireless network is selected—it's usually right, but don't assume it's automatically correct! By default, the password/passphrase is obfuscated by circle characters so that anyone looking over your shoulder can't see what you're typing. If it helps (and if your shoulder is clear), check the Show Password box. This can be really handy when you're typing a particularly long passphrase.

![]() Note WEP keys come in either hexadecimal (hex) or plain text (passphrase) varieties. Hex keys look similar to this in their 128-bit form:

Note WEP keys come in either hexadecimal (hex) or plain text (passphrase) varieties. Hex keys look similar to this in their 128-bit form: CB4C4189B1861E19BC9A9BDA59. In their 64-bit form, they will be shorter and may look similar to 4D9ED51E23. A passphrase will take the form of a single short sentence. In home and office environments, WPA networks are usually protected with passphrases. In larger corporate or academic environments, you might find that the network is protected with a WPA certificate.

Figure 7-6. Ubuntu is able to join WPA-protected wireless networks.

When you're finished, click the Connect button. You should see the NetworkManager icon start to animate as the program attempts to connect and find an IP address. After a few seconds, when the animation finishes and the icon switches to display signal strength, you should find yourself online.

If your computer doesn't seem to connect, try rebooting. If the hardware doesn't work after this, it might be that the drivers Ubuntu installed by default are incompatible with your network device. In this case, you can try using a Windows wireless network device driver, as described in the next section.

Should you find yourself in the unusual situation of needing to specify the IP address, subnet mask, and gateway for a wireless connection, you can do so using the manual configuration mode of NetworkManager, as outlined in the “Configuring an Ethernet Network Device” section earlier in this chapter. Simply follow the instructions in that section, but select the Wireless Connection entry in the list rather than Wired Connection. In the dialog box that appears, you'll see additional areas for entering your SSID and WEP/WPA protection details.

WEP VS. WPA

Installing Windows Wireless Network Device Drivers

NdisWrapper is effectively an open source driver (technically described as a kernel module) that allows Linux to use standard Windows drivers for wireless network devices. You might describe NdisWrapper as being a translation layer between the Linux kernel and the Windows drivers, which can be installed by using NdisWrapper's configuration tools.

You should use NdisWrapper in only one of two situations:

- Your wireless network hardware simply isn't recognized by Ubuntu: All you see when you click the NetworkManager icon is a Manual Configuration option; you don't see any wireless networks listed. Of course, you should first ensure that the wireless hardware in your computer is switched on—some notebooks offer the facility to deactivate it to save battery life.

- Your network hardware is recognized by Ubuntu but fails to work correctly or adequately when you configure it: Perhaps it is unable to associate with wireless base stations, or maybe you can't connect to WPA-enabled base stations and consider WEP too insecure for your surroundings. If this is the case, in addition to installing NdisWrapper, you'll need to undertake an additional step in order to blacklist the existing Ubuntu driver.

Using NdisWrapper is relatively simple, and just a handful of commands are required. However, getting hold of the necessary Windows driver files is harder work because, unfortunately, NdisWrapper isn't designed to work with the usual method of driver distribution: .exe files. Instead, NdisWrapper needs the specific .inf and .sys files that constitute the driver—effectively, the Windows system files. These are contained within the .exe file and must be manually extracted.

![]() Note Sometimes drivers are distributed as

Note Sometimes drivers are distributed as .zip files, in which case the relevant files are easy to get at. Keep your fingers crossed that this will be the case for your particular hardware!

NdisWrapper is far from perfect. Not all wireless devices have been proven to work with it, and it's not necessarily the case that a driver available for Windows will work under Linux. Sometimes trial and error is required. Annoyingly, Windows drivers sometimes appear to work but then prove unreliable. Some might stop working. Some might even crash your system. The best plan is simply to give it a try.

![]() Tip NdisWrapper gets better and better with every new release. This is why it's a good idea to update your system on a regular basis.

Tip NdisWrapper gets better and better with every new release. This is why it's a good idea to update your system on a regular basis.

In the instructions in this section, we explain how to make an Atheros AR5008 wireless network device that's built into an Apple MacBook work under Ubuntu using NdisWrapper. The instructions remain essentially the same for all types of wireless network hardware. However, some specific details, such as download addresses, will obviously differ.

First, you'll need to install the NdisWrapper software and then you can install the necessary Windows drivers. These steps will make your wireless network device available under Ubuntu. Then you can follow the instructions in the previous section to connect to that wireless network.

Installing the NdisWrapper Configuration Tools

NdisWrapper consists of two components: a kernel module and configuration tools. The kernel module comes as part of the default kernel package, so is installed by default, but you will need to install the configuration tools manually.

To do so, ensure you are online using a wired connection to your router have an active wired network connection, following the previous “Configuring an Ethernet Network Device” section. Then start up the Ubuntu Software Center, which you'll find under Applications. Do a search for windows wireless and install the Windows Wireless Drivers package which will come up in the search results. You will need to enter your password when prompted. Installing this package automatically installs not only the graphical Windows wireless driver installation tool, but also the underlying packages ndiswrapper-utils and ndiswrapper-common.

Installing the Windows Drivers

After the NdisWrapper configuration software is installed, you can install the Windows wireless network device drivers. There are several parts to the procedure:

- Identify the wireless network hardware and then source the appropriate Windows driver. If you're dual-booting with Windows, the drivers may already be available on your Windows partition.

- Extract the necessary

.sysand.inffiles from the driver archive (and possibly.binfiles, although this is rare). - You may need to “blacklist” (that is, tell the system to ignore) the built-in Ubuntu driver, so that NdisWrapper can associate with the hardware.

- Use the NdisWrapper configuration tool to install the Windows driver.

These steps are covered in the following sections. You will need another computer that's already online to download some files and check the NdisWrapper web site for information. If your computer dual-boots, you can use your Windows setup to do this, or if you have an Ethernet port on your computer, you could plug into a wired network.

Identifying Your Wireless Network Hardware and Sourcing Drivers

To identify the wireless network hardware for use with NdisWrapper, you need two pieces of information: the make and model of the hardware and the PCI ID number. The former is the make and model of the hardware as identified by Ubuntu as a result of system probing, rather than what's quoted on the packaging for the wireless network device or in its documentation. These details discovered by Ubuntu will usually relate to the manufacturer of the underlying components, rather than the company that assembled and marketed the computer. The PCI ID is two four-digit hexadecimal numbers used by your computer to identify the device internally (such as 168c:001a). The same PCI ID numbering system is used by both Windows and Ubuntu, which is why it's so useful in this instance.

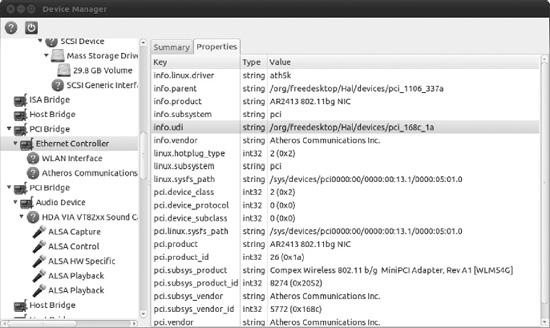

You can find both the PCI ID and the make/model information by using the Device Manager tool. Follow the instructions in the “Installing Device Manager” section earlier in this chapter if you haven't already installed this program. Then follow these steps:

- From the Panel, select Applications and startDevice Manager. In the left column, find the entry that reads Network Controller, Networking Wireless Control Interface, or WLAN Interface. You might also look for USB Interface, PCI Bridge, or 802.11 to exhaust your search. Then look at the corresponding summary in the right column, where you'll find the make and model of the hardware listed under the Vendor and Model headings. If no useful details are listed, you might need to click the parent entry in the list. On one test system, we found the WLAN Interface entry, but saw the make and model details only after we clicked the Ethernet Controller parent entry in the list on the left.

- Write down the make and model shown in Device Manager. For example, on a test notebook containing an Atheros wireless network device, the make and model read AR5001 Wireless Network Adapter. Remember that these details don't relate to those listed in the instruction manual or computer packaging (our notebook's specification lists the hardware simply as Built-in AirPort Extreme Wi-Fi). This is because Ubuntu is identifying the hardware generically, reading information from its component hardware.

- Click the Properties tab of Device Manager (if this isn't visible, click View

Device Properties) and look through the information there for a line that begins

Device Properties) and look through the information there for a line that begins info.udi. Look at the end of the line and make a note of the two sets of characters that are separated by an underscore and preceded bypci_. Look at Figure 7-7 for an example taken from our test machine. Yours may differ, but the line should always end withpci_and then the digits. If it doesn't, you have selected the wrong entry in the list of devices on the left. Try examining a different entry, such as the parent of the entry in the list. - Write down the characters following

pci_at the end of theinfo.udiline. Written alongside each other, the two sets of digits that are separated by an underscore form the all-important PCI ID number. In written form, they're usually separated by a colon. If either of the sets of letters or numbers is fewer than four characters long, simply add zeros before them in order to make four characters. In our test machine, the end of theinfo.udiline reads168c_1a. We add two zeros before1c, making a complete PCI ID of168c:001a. On another PC, the end of the line reads168c_13. Adding two zeros before13gives a PCI ID of168c:0013. - Using another computer that's able to go online, visit

http://sourceforge.net/apps/mediawiki/ndiswrapper/index.php. Under the Documentation heading, click the “List of known working devices” link. This is a community-generated listing of the wireless network devices that have been proven to work with NdisWrapper.

Figure 7-7. Find the PCI ID of your wireless network hardware by looking at the end of the

info.udiline. Tip The URL in step 5 was correct as this book went to press. If you find it no longer accurate, search Google, using NdisWrapper list as a search term.

Tip The URL in step 5 was correct as this book went to press. If you find it no longer accurate, search Google, using NdisWrapper list as a search term. - The “known to work” cards are grouped in alphabetical order. Select the appropriate list based on the card manufacturer's name. (Remember to use the name you discovered using Device Manager in steps 1 and 2, and not the official name in the computer's manual or packaging.)

- Using the search function of your browser (Ctrl+F within Firefox), look for the PCI ID number you noted earlier, in the format described in step 4. For the example in Figure 7-7, we would search for 168c:001a. In the list, look to match the following things, presented in order of importance:

- The PCI ID

- The model name of the wireless hardware, as reported by Device Manager (listed on the Summary tab)

- The manufacturer and model of the notebook, as mentioned on its case or within its documentation

- It's likely many entries in the list may match your PCI ID, so search until you find the one that best matches the model of the hardware. If there are still many matches, search until you find an entry that matches the manufacturer and model of the notebook. You might not be lucky enough to find an exact match for the notebook manufacturer and model, however, and you might need to select the most likely choice. Use your common sense and judgment. If your notebook is manufactured by ASUS, for example, but you can't find the drivers for the exact model, then choose drivers for another ASUS model.

Caution Watch out for any mention of

Caution Watch out for any mention of x86_64in the description of the driver file. This indicates that the entry in the list relates to 64-bit Linux. The version of Ubuntu supplied with this book is 32-bit. If you encounter an entry relating tox86_64, keep searching. - Look within the entry in the list for a direct link to the driver file. Sometimes this isn't given, and a manufacturer web site address is mentioned, which you can visit and navigate through to the driver download section (usually under the Support section on the web site). Download the Windows driver release.

Extracting the Driver Components

After downloading the drivers, you'll need to extract the .sys and .inf files relevant to your wireless network hardware. These are all that NdisWrapper needs, and the rest of the driver files can be discarded. However, extracting the files can be hard to do, because often they're contained within an .exe file. (Most driver .exe files are actually self-extracting archive files.) Additionally, the driver file might contain drivers for several different models of hardware, and it's necessary to identify the particular driver .inf file relevant to your wireless network device.

If the driver you've downloaded is a .zip file, your task will probably be much easier. Simply double-click the downloaded .zip file to look within it for the directory containing the actual driver files.

If the driver is an .exe file, it's necessary to extract the files within it. With any luck, you might be able to do this by using an archive tool like WinZip (www.winzip.com), assuming that you've downloaded the file using Windows. Simply open the archive by using the File ![]() Open menu option within WinZip. You may have to select All Files from the File Type drop-down list in order for the

Open menu option within WinZip. You may have to select All Files from the File Type drop-down list in order for the .exe file to show up in the file list. However, if you're using Windows, we recommend an open source and free-of-charge program called Universal Extractor, which can be downloaded from www.legroom.net/software/uniextract. This program can extract files from virtually every kind of archive, including most driver installation files. After it is installed, simply right-click the installation .exe file, and select UniExtract to Subdir. This will then create a new folder in the same directory as the downloaded file, containing the contents of the installer file.

After you've extracted the files within your downloaded driver file, look for the files you need. The driver files will likely be contained in a folder called something like Driver or named after the operating system, like Win_XP. After you've found the relevant directory, look for .inf, .sys, and .bin files (although you may not find any .bin files; they're used in only a handful of drivers). You can ignore any other files, such as .cab and .cat files. Click and drag the .inf, .sys, and .bin files to a separate folder.

The task now is to find the .inf file for your hardware. If there's more than one, you'll need to search each until you find the one you need. You need to look for text that corresponds to the PCI ID you noted earlier. Open the first .inf file in a text editor (double-clicking will do this in Windows) and, using the search tool, search for the first part of the PCI ID, as discovered earlier. For the example in Figure 7-7, we would search for 168c. If you don't find it within the file, move on to the next .inf file and search again. When you get a search match, it will probably be in a long line of text and to the right of the text VEN_. Then look farther along that line to see if the second part of the PCI ID is mentioned, probably to the right of the text that reads DEV_. In the case of the driver file we downloaded for the example, the entire line within the .inf file read as follows (the two component PCI ID parts are shown in bold):

%ATHER.DeviceDesc.001B% = ATHER_DEV_001B.ndi, PCIVEN_168C&DEV_001A

If you find both component parts of the PCI ID in the line, as in this example, then you've found the .inf file you need. (In fact, you'll probably find many lines matching what you need, which is fine.)

You must now transfer the .inf file, along with the .sys and .bin files (if any .bin files were included with the driver), to the computer on which you want to install the drivers. This can be done by putting them onto a floppy disk, CD, or USB memory stick. Create a new directory called driver on the Desktop and save them there.

Your procedure from this point depends on whether Ubuntu recognized your wireless networking device when you first booted but was unable to make it work correctly. If it did, you will need to blacklist the built-in driver so that NdisWrapper can associate with the hardware. If the device wasn't recognized, you can skip straight to the “Using NdisWrapper to Install the Drivers” section.

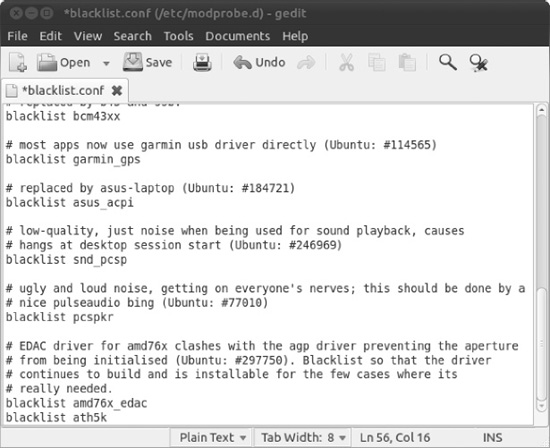

Blacklisting Existing Drivers

To blacklist the existing built-in driver that didn't work with your wireless device, you need to find out the name of the kernel module and then add it to the /etc/modprobe.d/blacklist file. Here are the steps:

- From the Panel, select Applications and Open Device Manager.) Next select the entry in the list for your wireless network device. This is the one you discovered in steps 1 and 2 earlier, in the “Identifying Your Wireless Network Hardware and Sourcing Drivers” section.

- Click the Properties tab (if this isn't visible, click View

Device Properties) and look for the line that begins

Device Properties) and look for the line that begins info.linux.driver. Then look in the Value column and make a note of what's there. For example, on one of our test notebooks, the Value column readath5k. Close Device Manager. - Hold down the Alt key on your keyboard and press F2. This will bring up the Run Application dialog. Type the following to open the

blacklistconfiguration file in the Gedit text editor:gksu gedit /etc/modprobe.d/blacklist.conf - Click Run and enter your password when prompted.

- At the bottom of the file, type the following on a new line:

blacklist modulename - Replace

modulenamewith the name of the module you discovered earlier. For example, on our test system, we typed the following (as shown in Figure 7-8):blacklist ath5k - Save the file and then reboot your computer.

You should now find that the wireless network device is no longer visible when you click the NetworkManager icon, and all you see is a Manual Configuration option. This is good, because it means the hardware no longer has a driver attached, and you can now tell NdisWrapper to use the hardware.

Figure 7-8. To stop Ubuntu from loading its own drivers, you may need to blacklist the module.

Using NdisWrapper to Install the Drivers

On the Ubuntu computer on which you want to install the drivers, you should now have the .inf file from the previous steps, plus the .sys and possibly .bin files that constitute the driver. You should have copied these files from the removable storage device into a new folder on your Desktop named driver.

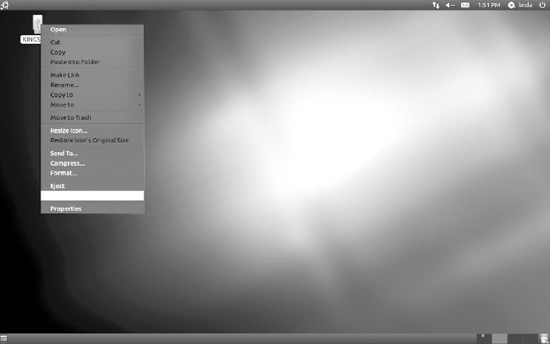

![]() Note If you've used a USB memory stick to transfer the files, its icon should appear automatically on the Desktop as soon as it's inserted. When you've finished with it, right-click it and select Unmount. You must do this before physically removing any kind of USB memory device, as explained later in this chapter.

Note If you've used a USB memory stick to transfer the files, its icon should appear automatically on the Desktop as soon as it's inserted. When you've finished with it, right-click it and select Unmount. You must do this before physically removing any kind of USB memory device, as explained later in this chapter.

To install the driver by using NdisWrapper, follow these instructions:

- From the panel, select Applications and in the Search bar, type windows. This will show an icon for the Windows Wireless Drivers application. If you haven' t installed it yet, you'll see it in the Apps Available for Download section. If this is the case, just click it to start the installation. Next, start the Windows Wireless Drivers application. Enter your password when prompted.

- Click the Install New Driver button.

- The Install Driver dialog box appears, prompting you to select the

.inffile for your wireless device. Click the Location drop-down list to open a file-browsing dialog box. - Navigate to the

.inffile you copied to your system, which you have placed in thedriverfolder on your Desktop. Double-click the Desktop folder and then double- click thedriverfolder listed in the right column. Select the.inffile you copied in thedriverfolder and then click the Open button. - Back in the Install Driver dialog box, click the Install button.

- At this point, you should see the driver listed at the left column of the Wireless Network Drivers dialog box. It specifies the name of the driver installed and whether the hardware is installed. If it says the hardware isn't installed, you've probably selected the wrong

.inffile, or might be using the wrong driver file. Return to the previous sections and try to get an alternative Windows driver. - No reboot is necessary, and your wireless network card should work immediately. To test whether the driver works, click the NetworkManager icon and see if there are wireless networks listed. If it works, click Close to exit the Wireless Network Drivers dialog box.

Following this, you should find that the network device is available for configuration. Follow the earlier instructions for connecting to a wireless network.

Removing NdisWrapper Drivers

As mentioned earlier, although NdisWrapper can solve a lot of headaches with nonworking wireless hardware, it isn't perfect. You might find that the Windows driver you install simply doesn't work. In such a case, you can download a different version of the driver and try again. But first you'll need to remove the existing driver.

From the Applications menu in the panel, selectWindows Wireless Drivers and enter your password when prompted. In the Windows Network Drivers dialog box, select the driver you want to remove in the left column and click Remove Driver. Click Yes when prompted to confirm the removal. Click Close to exit the tool.

SECURE CONNECTIONS ON THE NET

Connecting to a Mobile Broadband Network

Many countries now have widespread 3G cellular networks capable of delivering data at broadband speeds to mobile devices. Smartphones now come with 3G capability by default, with 3G USB adapters (“dongles”) to plug into your notebook now commonplace on pay-as-you-go or contract arrangements. Higher-end notebooks and Netbooks now come with mobile broadband adapters built as standard.

Ubuntu offers excellent support for mobile broadband devices, whether you want to connect via a 3G USB adapter plugged into your notebook, an inbuilt 3G adapter, or your 3G-enabled cellphone connected (“tethered”) via USB cable.

You can set up your mobile broadband device as follows:

- Connect your 3G device (dongle or cellphone) to your notebook:

- A dongle connected via USB cable should be instantly recognized.

- Cellphones will generally need to be switched into modem mode, and you will need to consult your manufacturer's documentation for details. For example, when you plug a Nokia smartphone into a notebook, a dialog will appear on the phone giving you the option of switching to Mass Storage Mode or PC Suite Mode. Select the latter to make it act as a modem.

- If your notebook has a built-in 3G device, make sure it's switched on.

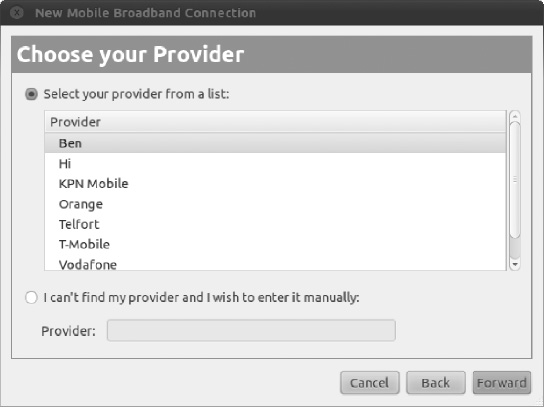

- Click the NetworkManager icon in the top panel of your Ubuntu Desktop. If your 3G device has been recognized, you should see a extra heading of Mobile Broadband, and under it ”New Mobile Broadband (GSM) connection,” which you should click on to start the New Mobile Broadband Connection setup wizard.

- The three simple steps in this wizard are:

- Choose Your Provider's Country: This will probably be correctly set already, based on the regional and language choices you made when you installed Ubuntu, but check it anyway before you click Forward.

- Choose Your Provider: You should see a list of all the 3G providers operating in your country. Choose yours. In the unlikely event of your provider not being listed, you can enter the name manually. Click Forward.

Figure 7-9. Ubuntu's mobile broadband connection wizard makes it straightforward to set up a 3G link.

- Choose Your Billing Plan: Several pre-set options will be shown in the “Select your plan” drop-down, depending on the options offered by your provider. For Vodafone UK, for example, the options are Contract, Prepaid, TopUp, and Go. The correct plan name for your 3G device should be there, but if it's not, there is an additional option of “My plan is not listed,” which will let you set the APN (Access Point Name) manually. (You will have to ask your provider for this information). Click Forward, check the settings, and click Apply.

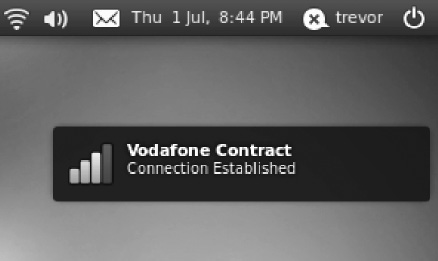

If you're within a 3G coverage area, your mobile broadband device should now make a connection, and all necessary settings such as IP address, gateway, and domain name servers should be automatically configured.

Figure 7-10. Uh-oh. Now that you're set up with a high-speed mobile broadband connection, your boss will expect you to be hard at work wherever you are!

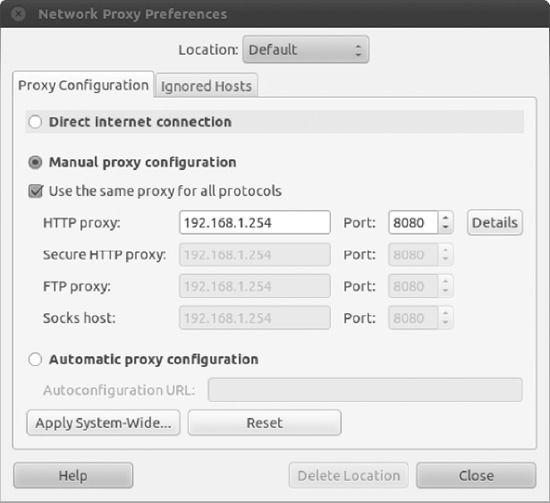

Working with a Proxy Server

Some networks in offices, schools, and universities require that you use a web proxy (often referred to as an HTTP proxy). A proxy is a server computer that provides additional security by providing a single portal to all web pages. It also helps speed up Internet access by storing frequently accessed pages. This means that if ten people request the same web page, there's no need to get the same ten pieces of data from the Internet. The proxy computer can send them its own copies.

You'll need to speak to your system administrator to see whether your location uses a proxy. If it does, your administrator will most likely give you an address, which may take the form of a web address (a URL) or an IP address. When you have this information, follow these steps to configure the proxy:

- Open Network Proxy Preferences (from the panel select Applications and in the search bar type Proxy).

- On the Proxy Configuration tab, choose one of the three types of proxy configuration:

- By default, the Direct Internet Connection option is selected, meaning that network traffic is routed directly, without using a proxy.

- Manual Proxy Configuration enables you to set the proxy servers and respective ports for HTTP Proxy, Secure HTTP Proxy, FTP Proxy, and Socks Host. You can fill in this information based on the settings you received from your system administrator. If you were provided with one proxy for Internet access, select the Use the Same Proxy for All Protocols check box and fill in the details for the HTTP proxy and port, as shown in Figure 7-11. If your proxy uses authentication, click the Details button. In the HTTP Proxy Details dialog box, select the Use Authentication check box and then supply the username and password. Click the Close button.

- Automatic Proxy Configuration allows you to enter the link (URL) to discover the proxy settings at your location.

- On the Ignored Hosts tab, you can set the list of sites that will bypass the proxy. By default, any site hosted on your own computer is bypassed. You can add and remove sites as well. You normally add intranet (internal) web sites to this list.

- Click the Close button after you're finished making changes to the proxy settings.

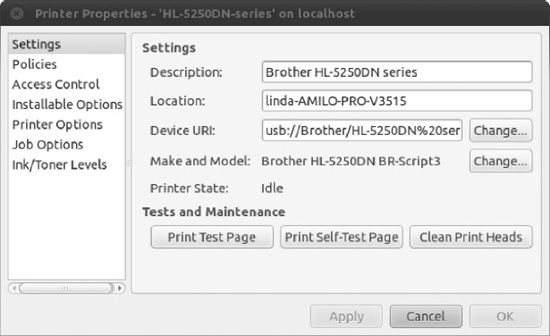

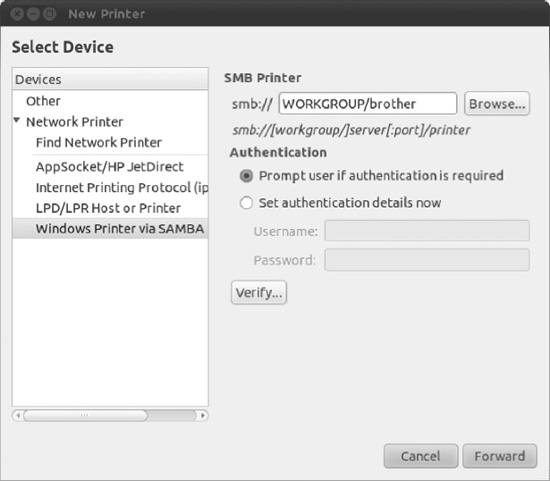

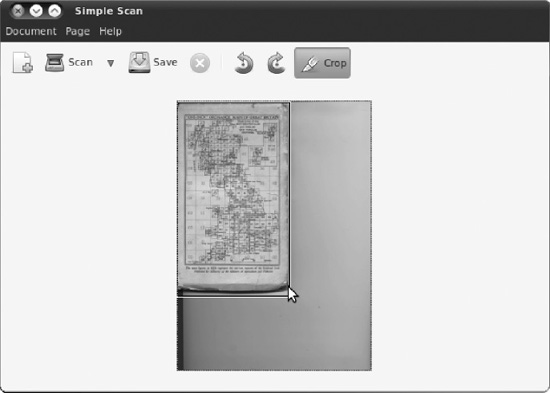

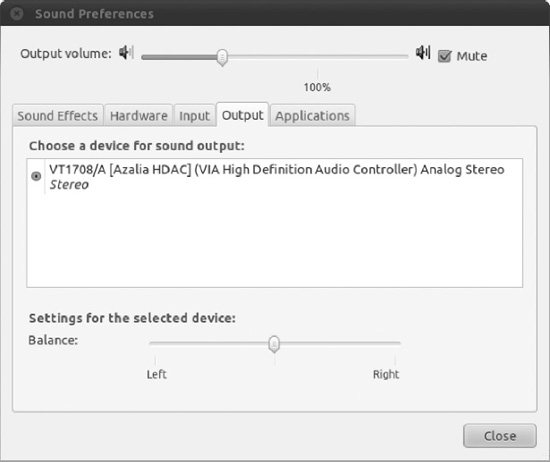

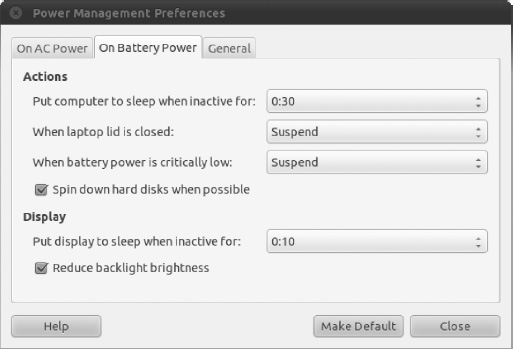

Figure 7-11. Proxy settings can be configured for a variety of locations.