Chapter 3. Kicking the Tires

Walter Murch edited the motion picture K-19: The Widowmaker on an Avid editing system in 2002 at The Lot.

EARLY JANUARY 2002—WEST HOLLYWOOD, CA

Walter Murch is at the former Warner Hollywood Studio, now called The Lot, editing K-19, starring Harrison Ford and Liam Neeson, and directed by Kathryn Bigelow. His first assistant, Sean Cullen, comes into the room. Murch is editing on his Avid system. He works standing up, the way some writers do. “Walter,” Sean asks during a pause, “what do you think about this Final Cut Pro thing?”

Apple Computer’s Final Cut is considered to be a “prosumer” application, midway between professional and consumer, though it is widely used to edit documentaries, TV commercials, and low-budget independent films. Hobbyists, students, and filmmaker wannabes love it because it’s cheap and easy to learn. For a film editor of Murch’s stature to consider using FCP on a big movie could presage the long-predicted convergence of consumer-level digital video tools and the Hollywood film industry.

“Hmm,” Walter murmurs. “Let’s keep an eye on it.” An understated response, but to people who know him as well as Sean does, it means, “I’m interested!”

Over the course of nearly eight years, Cullen had worked at Murch’s side on The English Patient, The Talented Mr. Ripley, the restored Orson Welles classic, Touch of Evil, and Apocalypse Now Redux. They make a great partnership. Cullen is fearless when facing technological challenges. At the Yale School of Drama he received an MFA in Technical Design and Production in 1994. Cullen’s master’s thesis on motion control in theater included designs for a new Apple Macintosh interface. Cullen knows that Murch’s commitment to advancing film and sound technology goes back to when Murch got started in feature films in 1969, on The Rain People for Francis Ford Coppola—the first American movie to be edited (by Barry Malkin) on a flatbed Steenbeck editing table and re-recorded (by Murch) on a KEM flatbed mixing system. Ten years later, on Apocalypse Now, Murch and Coppola invented what later became known as the “5.1” sound format for movies when Murch mixed the film’s soundtrack (on cinema’s first automated mixing board) so helicopters could be heard flying in 360 degrees around the theater. Only problem was, no audio system could accommodate the effect then, so Coppola had speakers added or rewired in movie houses across the country, paying out of his own pocket. In the 1990s, this pioneering audio technology filtered down to consumers, who could begin listening to “surround sound” in their living rooms. So now, having spent his career seeking out and often inventing breakthroughs in post-production technologies, it was perfectly in character for Murch to explore the possibility of changing editing platforms for Cold Mountain.

Sean Cullen has worked as an assistant editor with Walter Murch since 1994. Prior to his film work, Cullen did technical design at the San Francisco Opera and was technical director at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre.

When Apple Macintosh computers arrived in the mid-1980s, Walter became a fan, and not just for personal use. He always had a Mac in the edit suite for note-taking and logging information. If there is a filmmaker who personified Apple’s “Think Different” campaign, it is Walter Murch.

He had migrated from film-based editing to the Avid digital system in 1995 on The English Patient, though his initial motivation had nothing to do with technology per se. Murch needed to work out of his home in the Bay Area while filming continued on location in Italy and Tunisia. His son, Walter, had to undergo emergency surgery for a brain tumor, and it was only by going digital that Murch could stay near his son in California and keep up with the schedule. His Academy Award for Best Editing on The English Patient made it the first such Oscar for a film edited on a non-linear digital system.

By the late 1990s Avid had a strong foothold in the film industry, as well as in television news and advertising, where it first made its mark. But Murch and Cullen were looking for an alternative.

Avid, headquartered in Tewksbury, Massachusetts, has a reputation among film editors and assistants for holding onto useful but expensive improvements for years at a time. Cullen and other assistant editors find the company’s backup support sketchy. Cullen says, and other assistant editors concur, that Avid systems are not easily accessible for troubleshooting problems. So a system crash can be a real crisis, often requiring an Avid-certified technician to help them recover, which can cost an editor days of work. Avid technicians have been known to ascribe problems to configurations that use non-Avid peripherals, such as an NEC monitor. Cullen describes using an Avid to be, “like dancing with a gorilla, and the gorilla always leads.” Murch and Cullen were looking for a digital editing system that could give them more flexibility, would cost less (affording them more workstations), and if it did crash, one they could more easily fix on their own.

With their gift for problem solving, appreciation for Apple’s creative tools, and zest for challenges beyond mere editing, Murch and Cullen were ready to consider Apple’s Final Cut Pro, even if it hadn’t been fully road-tested.

Just for fun, when the two were editing Apocalypse Now Redux at American Zoetrope in San Francisco in 1999 and 2000, Sean tried the newly released Final Cut Pro 1.0. The immediate problems with the application had more to do with housekeeping than anything else. With its corresponding FilmLogic software, FCP could track only key numbers—the coding system for tracking every frame of film negative—then used by Kodak. But Apocalypse Now had been shot in the 1970s, so the alpha/numeric stamps on its negative were long out of date. “I could probably get around that,” says Sean, “but it was too ‘ka-chunk’—too labor-intensive.”

Sound mixing The Godfather: Part II, 1974. Left to right, Mark Berger, Francis Ford Coppola, Walter Murch.

Murch first worked with Francis Ford Coppola on the motion picture, The Rain People (1969). Both enjoy seeking out the latest technical filmmaking advances, and in some cases, inventing them.

Murch holds his two Oscar awards for editing and sound mixing The English Patient (1996), directed by Anthony Minghella.

By 2002, two years later, Final Cut Pro had reached version 3.0. For Murch and Cullen, the prospect of doing an $80 million studio film on software costing $995 is too seductive to disregard, as is the prospect of living in Apple’s friendly interface and object-oriented, cut-and-paste world. With Walter’s encouragement, Sean uses his spare time to do technical research, pore over Apple’s Web site, and play with the software on his laptop. He starts coming across an outfit in West Hollywood called DigitalFilm Tree. “When I did a Google search, DigitalFilm Tree kept coming up—either a reference to them, or to Ramy Katrib, who had spoken at some conference.” Sean talks to Walter again: “There’s these guys in town, DigitalFilm Tree, and I’d like to give them a call. How would you feel about me saying we might do the next show on Final Cut?”

“Sure,” Walter says. “Let’s see what develops.”

Office of DigitalFilm Tree, located on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles. Sean Cullen contacted the company to find out more about using Final Cut Pro.

The historic Sentinel Building in San Francisco, offices of American Zoetrope, Francis Ford Coppola’s production company. Here, while working on Apocalypse Now Redux (2001) with Murch, Sean Cullen first experimented with Apple’s Final Cut Pro 1.0 to see how it handled film.

Ramy Katrib had formed DigitalFilm Tree in 1999 expressly to help film editors, as opposed to video editors, learn and properly configure Final Cut Pro. FCP wasn’t originally released with the idea of editing film, so there was a dearth of reliable information and technical support. Katrib quickly found a niche within the post-production community of editors looking for advice and TV and motion picture productions seeking consultation. The information went full circle, since Apple itself came to DFT for FCP development ideas and feedback from users in the field.

At the beginning of 2002, serious planning for post-production on Cold Mountain hasn’t even started. All Sean and Walter know for sure is that Anthony Minghella is directing; they don’t know where the film is going to be shot or edited. Tom Cruise is actively negotiating to take the role of Inman, which Jude Law will eventually play. Cullen and Murch understand this much: Cold Mountain is going to be a big-budget, high-profile, studio-backed film with a star-driven cast. Characteristic of the motion picture business, there are no deals, contracts, or handshakes. Anthony simply sent Murch an early draft of the script in the summer of 2001, and Walter enthusiastically agreed to edit the film. Still, it was incumbent on Cullen to be careful when contacting people that word about the project didn’t get out.

When Cullen calls DigitalFilm Tree, Scott Witman picks up the phone. “I’m thinking about doing this film and using Final Cut Pro,” Cullen says. “I want to talk to you guys about what’s possible and what you’ve done before, and just whether or not you think this could even have a chance of working.”

Witman’s answer might have ended the whole venture right then and there. “Well, we’re pretty busy right now,” he says. “A lot of people are asking for advice. We can’t give out free help any more.”

Sean assures Witman he has a professional relationship in mind: “No, no, not free. We’d pay you to consult—to find out what’s going on.”

“In the first conversation,” Sean recalls, “I sort of held back a little bit. I said it’s a large film, that we’d probably shoot half a million feet, and shoot for a number of months—maybe six months. They were starting to get interested. Witman said, ‘We’ll give you a call back.’ I just left my first name and the phone number.”

With his dark bedroom eyes and customary three-day growth of beard, the founder of DigitalFilm Tree is known among women in the digital film community as “beautiful Ramy.” He first began exploring the unmapped terrain between film and desktop digital video in 1998 while working the night shift at Magic Film & Video Works in Burbank. It was then considered the largest negative-cutting house in the world, where film negative was conformed for shows like E.R., NYPD Blue, and Spin City, along with most of New Line’s feature films. Ramy was the telecine operator, doing film-to-video transfers.

Ramy Katrib, founder and president of DigitalFilm Tree.

“When you walked in, the smell of chemicals and cement just overwhelmed you,” says Ramy. “They had ten splicing stations, old German machines with foot pedals, all going click-click, click-click. At the time that I worked there they had 70 employees, all negative cutting.” (As a measure of digital editing’s invasion of the film world, only 15 workers remain.)

“Negative cutting is the scariest post work I’ve ever seen,” says Ramy. “If you make an error you lose your job. I hated it.” But in retrospect, the experience was fortuitous both for Ramy Katrib and for Walter Murch. “I stopped being scared of film,” says Ramy. “I touched it. I rolled it.”

Ramy Katrib’s life began far from Hollywood. He was born in Beirut in 1970 of Lebanese-Christian parents. His father was an evangelist, his mother an English teacher. They settled in Loma Linda, east of Los Angeles, in 1975. From there Ramy went to U.C. Riverside and to Columbia College in L.A., where he learned hands-on film crafts. “School was all about learning how to edit, how to shoot; I liked that,” he says. “But everyone in my family was freaking out. They perceived L.A. as Sin City, even though it was only 50 miles away.”

On off-hours from his job at Magic Film & Video Works, Ramy produced his own documentaries. “Of course I wanted to be a filmmaker, just like every Joe out here,” he says. One project—still unfinished—was about the writer Mardik Martin, who wrote Mean Streets and Raging Bull. The other documentary was about proton treatment—the convergence of nuclear particle physics and medical treatment. For that project, Ramy bought one of the first Canon XL-1 digital video cameras when they came on the market. He was spending his own money, so finding ways to work cheaply and quickly was always a priority. Avid, which sold its low-end machines at $100,000 or more, was out of the question. Having both film and digital video footage to edit, Ramy’s challenge was to find a way to get film footage into a cheap desktop digital video system, such as Adobe’s Premiere, and then get it out accurately. At the time, this was uncharted territory.

Edvin Mehrabyan, known as “The Finisher” for his top-notch negative cutting.

Ramy was on the verge of buying a Fast-601 edit system that had Avid-like capabilities but cost $13,000 when he heard about Final Cut Pro. The Mac computer and FCP software together cost less than $4,000.

Even though Katrib did telecines at Magic Film & Video on a machine using a sophisticated Silicon Graphics computer and operated a DaVinci color-correction workstation costing six figures, he didn’t own a personal computer or even use email at that time—hard to believe, given his desire for taking FCP beyond its domain. But Cullen doesn’t know any of that when he reaches out for help with FCP. All he knows is that Ramy and DigitalFilm Tree are at the nexus where film editing meets Final Cut Pro.

Ramy calls Sean back and asks what kind of help he needs.

“Right now, we’re trying to stay low profile,” Sean replies. “We don’t want anyone to say, ‘What are you talking about?’ and short circuit things. We want to keep it quiet. Is that something you can do?”

“Oh, absolutely,” Ramy replies.

Sean continues. “It’s Cold Mountain with Anthony Minghella. Walter Murch is the editor.”

Ramy pauses to catch his breath. “Whoa!”

By early 2002, Ramy had built DigitalFilm Tree into a considerable force with help from two colleagues at his old telecine job, Henry Santos and Edvin Mehrabyan. During long nights on the graveyard shift, the three discovered a shared interest in pushing computer-based, non-linear editing software past its original purposes. Mehrabyan, a Russian-Armenian, was supervising all the negative cutting at Magic. He was nicknamed “The Finisher,” says Ramy. “Everyone knew him. People who had botched negative cutting jobs would come to him in a crisis from all around Los Angeles. He could fix negative tears by artificially slicing on the frame line and splicing it himself.”

Santos started working at Magic a year or so after Ramy. He was 18 then, a kid out of high school, but he already had excellent skills as a colorist—the person who corrects hues and tones in film and video transfers. “He was a sharp kid,” says Ramy, “so I brought him in as an apprentice to work in telecine.” Ramy already was demonstrating the kind of entrepreneurial, team-building instincts that would later serve him well in making DigitalFilm Tree a reality.

The next principal to join DFT was Tim Serda, a Macromedia certification engineer who worked on Final Cut Pro, which then had the code name Key Grip. Serda had moved to Apple when it acquired the application from Macromedia.

Once he had his own Final Cut Pro software, Ramy brought his burgeoning brain trust together to see if they could force FCP to accurately cut film. An essential element—the missing link—was FilmLogic, an application for transplanting video’s 30 frame-per-second databases and edit lists into the realm of 24 frame film. Ramy located Loran Kary, the father of FilmLogic, and invited him to Los Angeles to join in the experiment. Without telling anyone, they all gathered at Magic Film & Video Works one weekend.

Loran Kary developed FilmLogic, a database for taking 30 frame-per-second video information and converting it into 24 frame film. Apple later acquired the program and renamed it CinemaTools.

Ramy had finagled Sony into lending him a $15,000 DVCAM DSR 2000 digital video deck for a week. “We did something really simple—we transferred film dailies to a DV format, which was unprecedented,” he said. “For us, that was like—whoa! No one was doing this. I took that tape home and put it my Final Cut system. I put it in my little DVCAM deck, lined it up, captured it. And it behaved the same way that video behaved on an Avid. I knew we were onto something. It was too dramatic. And the fact that I was even approaching a place where I’m doing something with film that wasn’t on an Avid Film Composer—I was just smart enough to know that this was big.”

The interface for FilmLogic, the application used in conjunction with Final Cut Pro to convert information for 30 frame-per-second digital video to 24 frame-per-second film.

The group’s accomplishment was considerable for two reasons: first, Final Cut Pro software had been tricked into doing something Apple never had in mind when it designed and released the product solely for video; and second, an affordable, open-format, user-friendly competitor to Avid was being hatched in front of their eyes. Within a year Apple caught on to the implications, bought FilmLogic, renamed it Cinema Tools, and hired its creator, Loran Kary.

“The day we documented that test was when we launched DigitalFilm Tree,” says Ramy. “I don’t know why I decided to document it, because really, if you go back to that day, no one thought anything about anything; it was just kind of hanging out. I even remember a little grumbling from some of the people because it was a 16-hour day. It was no money, no nothing. But we cut a sequence in my apartment, where my system was. We generated a cut list out of FilmLogic. We went back to Magic, and Edvin cut it. And it lined up. It was just like an Avid cut. It was perfect; and everyone was there to verify it.”

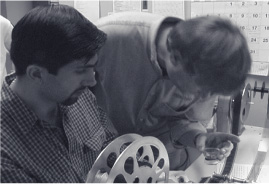

A test organized by Ramy Katrib in 2000 that proved Final Cut Pro, with FilmLogic, could accurately cut film.

Katrib, Edvin Mehrabyan, and Loran Kary prepare to begin the test in Katrib’s apartment.

“Once we did that test, I became an evangelist, like my dad,” says Ramy. “I was preaching it to everybody. And that’s when I started talking to Edvin and Henry—telling them this was going to change the whole landscape for film. We went through the process of hiring a lawyer, formed an LLC, and started DigitalFilm Tree.”

It’s nearly two years later when Sean Cullen drives out onto Santa Monica Boulevard from The Lot. He heads west toward Sunset Boulevard and finds DigitalFilm Tree’s home: a two-story English Tudor-style house, cater-corner from Larry Flynt’s Hustler Store. From the outside, the place looks like the location for Steve Martin’s failing production company in the film Bowfinger—a long-neglected, stereotypically noir Hollywood building. But once he goes inside, Sean sees the future of feature film editing.

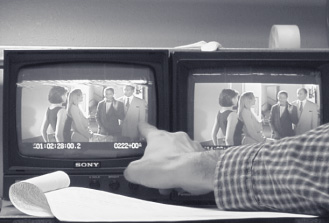

Video monitors show a sample scene being cut in Final Cut Pro.

Sean recalls that first encounter: “I outlined not only what I thought we might be doing, but some of the politics of Cold Mountain and a description of Walter’s personality. I told them he will say, ‘Oh, this is wrong. It’s off a few frames.’ I said, ‘You really want to be careful, because he’s always right. And you might say, ‘No, that’s in sync.’ And he’ll go, ‘No, it’s out of sync one frame early. Fix it, and then give me a call.’ And sure enough, it’s out of sync one frame early. I said, ‘Watch out, because Walter has a really sharp eye.’”

“The more we talked,” Sean says, “the more we realized we were perfect for each other. They were doing what nobody else was doing. They were groundbreaking because they were doing the first features. It was clear this was where the smart people were.” What had begun with DigitalFilm Tree saying, “We can’t give out free help,” quickly becomes “We’ll figure out the money later.”

Loran Kary uses a loupe to inspect cut camera negative—the end product of the successful Final Cut Pro test. Mehrabyan is on the left.

Cullen describes the sort of relationship he and Murch want to have with DFT. Changing editing platforms means they would need all kinds of troubleshooting and problem solving, especially since Final Cut Pro has never been used to edit a major feature film with so much footage. They will need to be in constant communication, night and day; the inevitable fire alarms will demand an instantaneous response. Sean needs to know if Ramy and DFT can provide that kind of backup and go the distance for well over a year. Barely containing his enthusiasm, Ramy says they can and will.

Cullen then talks about possible deal breakers. “There are a number of things that, unless they are provided to Walter, he isn’t going to do the film on Final Cut.” Sean tells DFT, “If we can’t make these things work—either because I don’t understand how they work, or they can’t work—then the deal is off, and we’ll do the show on Avid.’”

“Guys, the stuff on the right-hand monitor looks like crap.”

One requirement is being able to watch the same material on the computer screen and on the TV screen. By this, Cullen means that in addition to the normal computer monitor, Murch has to be able to use a large-screen TV in his edit room for viewing completed edits. Cullen also insists that both the computer and TV monitors be capable of displaying the same images, simultaneously, cleanly, and crisply by running digitized material at true 30 frames per second. Being a surrogate for the audience, the film editor needs to be immersed in the movie, free from technical distractions, even if he watches a single scene less than a minute long.

“I knew that Final Cut, when you took it out of the box, couldn’t support a reverse telecine process,” Cullen says later. “You couldn’t watch 30 frames per second on the TV. Avid does this, so I knew that we were going to have to do it. Walter needed to be able to have the record monitor and the TV both play back in real time, simultaneously, not switching one from the other.”

Ramy takes all these requirements in stride, telling Cullen they can be realized. To prove it, Ramy turns to their Final Cut Pro setup and runs some sample footage. Cullen isn’t impressed.

“Guys, the stuff on the right-hand monitor looks like crap,” he says.

“What do you mean?”

“Walter won’t go for that. That looks bad. It’s jumpy and tearing from the interlace.” For Cullen, the image is compromised and contains artifacts—lines that are jagged instead of straight—due to the low data rate by which media is being sent to the computer.

But Ramy sees the glass as half full. “Well, it’s not that bad,” he says.

“Okay, wait, stop,” says Sean. “We need to understand each other. If I say Walter isn’t going to go for it, he’s not going to go for it. And that isn’t good enough for us.”

“Well, we know we can get it better,” says Ramy, “just not on this machine.” Like many functions in the Final Cut Pro system, the data rate can be customized—in this case upward.

Sean is still dubious. “Okay, but I guarantee when Walter comes in, he’s going to need to see it looking really good on both the computer and the TV.”

Ramy later says, “It didn’t take very long to realize that Sean was a force of nature, a heavyweight. Sometimes when you talk to people, you can feel that some of it is registering and some of it isn’t. With Sean, everything was registering and he was coming back for more.”

One hugely threatening issue remains, and Sean, Ramy, and the others at DFT talk it through: the fact that Final Cut can create an Edit Decision List (EDL) for conforming the film workprint but cannot track subsequent changes to that list—an essential procedure in any big-budget feature.

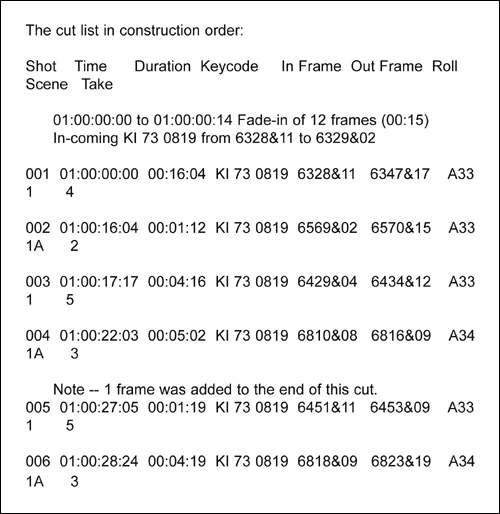

A cut list, or EDL, is the blueprint for how scenes of a film finally get put together. It lists the shots to be used, in order, with each beginning and end point, measured in feet and frames. All effects such as dissolves or fades are also noted. At the end of the editing, when the picture is “locked,” or declared finished, this cut list goes to the negative cutter. Up to that point the film that was originally exposed on the set has remained untouched, except to make the workprint. It’s been sealed in cans, safely locked away in the film lab vault. There is only one original camera negative, and it can never be replaced. Only when all the decision making on the picture editing is done, does the final negative cutting process begin.

An edit decision list (EDL), a database listing every cut in a movie that is generated by a digital editing system, such as Avid Film Composer or Final Cut Pro.

Negative cutting is done in a dust-free environment. The cutter wears white cotton gloves and makes splices using cement. There can be no mistakes. Each cement splice destroys one frame of negative, since the adjacent frame must be scraped to make a “hot splice.” Negative cutters work alone, for the most part. In the film business, they are the only crew members for whom a compulsive, sometimes neurotic personality is considered a job requirement, if not an asset. They work much like gem cutters, where a mistaken move can ruin the goods—except that a feature film negative is worth far more than most diamonds.

During post-production, the film editor is essentially creating the “pattern,” or template, that the negative cutter will later use to cut the whole cloth into a finished garment. That cut list must be exactly correct in referring to the original film negative. The basis for indexing all that film footage (114 miles of it in the case of Cold Mountain) is the key codes. Each frame of film has a unique address or marker. These alphanumeric inscriptions reside on the edge of the film negative, in the area outside the viewable frame. They occur once every foot (16 frames), pre-burned into the film stock when it is manufactured. A second set of tracking information is applied to the film workprint, or dailies. These are called edge numbers or print codes. They are stamped onto the edge of the film by an assistant using an Acmade numbering machine. The format is usually a seven-digit code, like a telephone number. The first three digits refer to the camera roll number, the last four to the footage. Different inking colors can be used to create sub-levels and categories. For example, you might code all footage using visual effects in red.

A sample of 35mm film showing negative key codes imprinted by Kodak at the time of manufacture. This system gives every frame of film its own unique address so editors can keep track of their whereabouts throughout the long process of film editing.

Keeping track of all the footage in a feature film is a major systems challenge. Typically, a two-hour feature film might have a shooting ratio of 20:1. That is, for every minute of film in the final release print, 20 minutes were shot. Even that shooting ratio is misleading, because a fair amount of film stock is wasted in normal operations: starts and stops, film run through the camera to thread it up, and hunks of leftovers that are not long enough to record a complete take (“short ends”). However, in some films, such as Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, the shooting ratio is much higher—100:1 or more.

The accounting method in day-to-day assembling of a film relies on the edge codes printed onto the workprint. These are what the editing team will use to conform the 35mm workprint to the arrangement of shots edited in the computer. Key codes on the negative don’t come into use until the end of the process, when the negative must be cut. However, both sets of numbers are encoded from the beginning, before editing irretrievably mixes up all the footage. With non-linear digital editing like Final Cut Pro or Avid, a lot of data—starting and ending key codes and print codes for each take—must be added manually by an assistant when the footage is digitized or brought into the computer.

Whether a film is edited on an upright Moviola, on a flatbed, or in a digital system such as Final Cut Pro, the same thing will eventually be delivered to the negative cutter: an EDL listing all the correct edit points. When a film is cut only using workprint, the edit list is manually written. The negative cutter also has the edited film workprint and its printed-through key codes as a guide for double-checking, but the list is paramount. When digitally editing, the alphanumeric key codes entered at the beginning remain embedded in the media files, hidden but available. They emerge in the cut list when it is generated on the computer.

Creating an EDL automatically is one of the most valuable timesaving benefits of non-linear editing. With a couple of keystrokes, you can produce a complex database that, in the analog world might take an assistant a week to make—with inadvertent errors a likelihood. EDLs from a non-linear system also have a built-in feature to check for any duplicate frames. Since every cut to the negative eliminates one neighboring frame (remember, it’s called “destructive editing”), the negative cutter needs to know ahead of time if any of those abutting film frames must be used somewhere else in the film. If so, an assistant will ask the lab to make a duplicate copy of the take in question, a dupe negative. Cut lists must be absolutely frame-accurate. Should a decision list go to the negative cutter with inaccuracies, disaster results. Needed frames may be mangled or—even worse—an incorrect version of the film may get printed at the lab.

Long before an EDL is required for the negative cutting, film assistants need a similar cut-by-cut database called a change list to do their work. The change list catalogs all the variations between two different edited versions of a film. The assistants use this to re-cut the workprint on their editing benches, conforming the projectable film to its digital counterpart. Sound editors also use the change lists to conform their soundtracks to match new versions; otherwise their audio work will be out of date or out of sync. Another beauty of digital editing is the ease with which this information can be communicated from the picture department to the sound editors.

Getting a reliable edit decision list out of Final Cut Pro was not a problem. But Cullen had to know if and when FCP would be able to generate dependable change lists. Did Apple at least have it in the works? Ramy replied that it was being developed, but he wasn’t sure it would be ready in time. Troubling news, but for an assistant film editor, there is no such thing as a perfect world. It helps, however, when variables such as this are known ahead of time.

All digital editing systems crash, lose media, or otherwise throw uncertainties into the path of a feature film barreling down the road to completion on a tight schedule. As Sean says, “I noticed working with the Avid on English Patient, things like media crashes and corruption all had the same amount of difficulty to solve. But when Avid told us, ‘That’s not a problem, just get over it,’ those were the things that really stuck in our minds. When they were open and up front about it, even though we were putting in the same amount of work, we thought, ‘Oh, that’s just part of the cost of using Avid.’”

“I didn’t want to get into a situation where I had suggested that we go the Final Cut route, knowing there were things that were going to be a problem,” Sean says. “Either not telling Walter, or minimizing problems, then having them come up. That’s always a pain.” Cullen wants to go through all the things with DigitalFilm Tree—both good and bad—that might materialize, to get a sense of how much of a problem they are going to be and how much energy it will take to do workarounds. Says Sean: “If it was something that wasn’t going to be fixed but I could solve, I could say to Walter, ‘It’s a problem, but I’ll take care of it.’ On an Avid, you’re taking care of things all the time. I knew there was going to be a certain amount of that going on.”

One of Final Cut Pro’s big advantages is price. Murch can have four fully loaded Final Cut Pro editing systems for less than the cost of one Avid system. Having four machines means backup and redundancy, thus avoiding project-wide crashes or breakdowns and making serious downtime much less likely. Apple’s Final Cut Pro system is relatively immune to serious crashes because it is a software-only system (except for a third-party card for digitizing) that is designed to run on Apple hardware. And because it can also run on a laptop, FCP gives an editing team great flexibility and mobility.

“I was immediately reminded of the fact that most kitchen stoves have four burners,” Walter says later. “When you’re cooking a big meal for the family you use all those burners. And in retrospect, looking back at all those shows I’ve done with two stations, it was very similar to trying to cook a banquet on two burners. There’s a lot of, ‘Well, I’ll take off the cauliflower and put that to one side. Meanwhile cook up the onions... Oops, the cauliflower has to go back on again!’ There’s just so much juggling because of all the different tasks you have to do at the same time.”

A “four-burner” configuration for Cold Mountain will provide one station for Walter to work on and a second for Sean to do syncing up of dailies, file management, and some editing. Of the two other stations, one will digitize “in” and the other will digitize “out.” That is, station three will be connected to a Beta SP videotape deck for the purpose of transposing videotapes of film dailies into the QuickTime digital files that FCP uses. Station four will take dailies, scenes, and assemblies from FCP and put them onto other media—sometimes VHS tapes but most often DVD—so that producers, the studio, and other post-production crew can view versions of the film as a work-in-progress.

Shawn Paper, film editor on Month of August (released in 2002), the first feature film to use Final Cut Pro.

“I enjoy collaborative work,” says Murch. “One of the profound implications of FCP is that it is so inexpensive that anyone with a PowerBook—and one of the machines we had was an old clamshell iBook—can download media and edit with it. So I was giving scenes to the assistants and apprentices for them to cut their teeth on. It’s a great teaching tool. Plus, it gave us a great deal of reliability and flexibility, in addition to being a system that I found completely transparent and enjoyable in the day-to-day cutting of the film.”

When Final Cut Pro first surfaced, the post-production community in Los Angeles didn’t take it seriously. It was not ready for an alternative to Avid. “People ridiculed it,” says Ramy. One day a film editor, Shawn Paper, who had always used the Avid system, came to Ramy and said, “I’ve got Final Cut Pro at home. Can I do this?” And Ramy said yes. And with help from DigitalFilm Tree, Paper cut the first feature film, Month of August, on Final Cut Pro.

That led to DFT working on several other motion pictures using FCP, such as Full Frontal in 2001, which was directed by Steven Soderbergh and edited by Sarah Flack, and featured David Duchovny, Catherine Keener, and Julia Roberts. DFT also supplied Final Cut Pro systems for The Rules of Attraction (2002), directed by Roger Avary and edited by Sharon Rutter, starring James Van Der Beek and Shannyn Sossamon. Then, in the spring of 2002, Sean Cullen and Cold Mountain walked in the door.

Since the first meeting went well, Sean wants to bring Walter to DigitalFilm Tree to “kick the tires,” as he put it. He requests a system that looks good on both monitors—record and playback—and he wants some footage available that Walter can cut. He reminds DFT that they still have made no financial arrangement. They tell Sean not to worry.

In the meantime, Ramy runs out to buy the second edition of Murch’s 1995 classic book on film editing, In the Blink of an Eye. He is shocked to find a long passage about Final Cut Pro and FilmLogic in the afterword. (That section, new to the 2001 edition, is called “Digital Film Editing: Past, Present and Imagined Future,” and fills fully half of the book’s 146 pages.) “How does Walter know about this stuff?” Ramy remembers thinking. “It was so new. When I told some of the people we work with that the next Final Cut Pro project could be for Walter Murch, they freaked out. People who come from the editing community were stunned. I wondered, ‘Why is Walter Murch even talking to us? We’re nobody.’”

Sean phones DFT a few days before he brings Walter to the company. “How’s it going? Are you guys ready?”

“Yeah, we’re all ready.”

“How good does the video look?”

“It looks great.”

“I need to know: does it look great, or does it look so-so? Because if it looks so-so, I’ll get Walter ready now.”

“No, it looks great.”

Sean doesn’t prompt Walter before they go together to see DigitalFilm Tree. Nevertheless, on the way over, he zeroes in on the potential problem.

Walter Murch’s book on film editing theory and practice, In the Blink of an Eye.

“How’s the video?” Walter wants to know.

“It should be good,” Sean tells him.

Walter and Sean arrive at DFT and are introduced to Edvin Mehrabyan, Tim Serda, Walter Shires, John Taylor, and Dan Fort. The group then goes into the edit suite, which doubles as a training room for Final Cut Pro users and students. Ramy and his team are smiling, feeling both sanguine and nervous. They have a brief discussion about what Murch and Cullen want to accomplish while they are there, and then... it’s showtime!

As Sean later remembers it, “The video image was good. Walter said it could get better, but it was definitely passable, that he could do a show on it.” Though he tries not to show it, Ramy is ecstatic.

Later, Ramy recalls the impact of having Walter Murch come to DigitalFilm Tree: “It wasn’t simply his award-winning credits. It wasn’t that he was the first Academy Award-winning editor we worked with. He was the third or fourth. It was the fact that he was wearing tennis shoes when he came here. The fact that he was down to earth, that he later sat right down to check his email. That’s when we started to appreciate that he was different. He would ask things and we would just look at each other. He wasn’t a pushover; his questions were brutal.” A silent stare from Murch can be intimidating, even for someone who is technically savvy. Ramy, freely admitting he was the least knowledgeable about technical things and editing, describes how during that first session with Murch at DFT, he intentionally put himself out there with incomplete information to force the other DFT people to chime in with more complete answers to Murch’s questions.

“We mostly told him what was bad about Final Cut,” Ramy says. “It will do things that are heart-stopping, and we knew this going in. We never sat down and tried to sell him. After you have spent months cutting a show, FCP can dish up an error message saying, ‘Sequence won’t open,’ or ‘File not found,’” Ramy says. One editor describes FCP as “jackass-put-together, dumb-shit code, a bullshit program.” Even Ramy, who is an evangelist, admits FCP is an application often constructed out of “sheer voodoo.” He says: “Things happen that make no logical sense. You can lose your project, or you’re doing a color-correction job, and all of a sudden it’s gone, like vapor, and you can’t find it.” Given that FCP is an application first developed by Macromedia, then rushed into its first release version by Apple, Ramy calls it “a hack on top of a hack.”

Still at DFT, Walter goes through what Sean calls “the artistic stuff”: how the interface feels, what other editors had problems with, how fast it is and how quickly sequences load—things that he knew he would be doing day in and day out. In his mind, he was weighing FCP against the Avid. “A lot of his questions, as mine had been, were referenced off the Avid,” Sean said. “We were on an Avid, we had used Avid. We knew the Avid problems, knew the Avid strengths. So a lot of it was comparing. Very much to DigitalFilm Tree’s credit, they never said, ‘Final Cut’s better.’ They were very honest: ‘Well, Avid is better at that, but Final Cut is still passable.’ Or, ‘Final Cut really doesn’t have that,’ or ‘Final Cut is much better at that than the Avid.’”

Three major concerns emerge by the end of the meeting at DFT: 1) how to generate accurate change lists to keep a 35mm film workprint version conformed to match the Final Cut Pro version; 2) how to transfer soundtracks on Walter’s machine—“sequence information”—to the sound editors’ ProTools workstations; and 3) whether FCP could swallow, digest, and play back so much media—a first assembly that might exceed five hours of running time. Sean admits he is less concerned about list-making functions because he won’t need them for nearly a year. DFT isn’t too worried about transferability of sequence information since they had access to programmers and engineers who are experienced with OMF (Open Media Format, the file format for transferring audio material between applications). DFT also knows that Apple is working on developments that might give Final Cut Pro a mechanism for exporting edited audio tracks to digital audio workstations (DAW).

Walter isn’t so easily satisfied, however. “He really wanted to know about the sequence transfer to the sound department,” Sean recalls, “because he’s very much a sound person, and he has a lot of experience working with sound departments. Walter knows that the more friction you have [between picture and sound departments], the harder the whole process is.”

“What if Apple doesn’t do it?” Walter asks. “What are we going to do?” The question hangs in the air.

In a way, the money discussion is easier. It comes down to Ramy saying: “Just as long as you take us on board when you do the film, this will all be pro bono work. And if you don’t take us, we’ll get a lot of good experience researching this.”

Sean and Walter come away from their meeting feeling that DigitalFilm Tree will be their “men in Havana,” but they haven’t quite decided to adopt FCP. They need to know more. Sean, Walter, and DFT agree to divide the next round of research. Walter will talk to editors who have done work on Final Cut Pro. Sean will investigate whether FileMaker, the program they use for organizing their code books, logs, and databases, will work well with Final Cut. DFT will look into the remaining technical hurdles and design issues.

After the meeting, Ramy calls his contacts at Apple to give them the headline: Walter Murch is interested in using Final Cut Pro on his next feature film. “I’m chatting with Apple people who are enthusiastic—I’m talking to higher tier managers, foot soldiers, not with the people who run the company. And I’m telling them that Walter’s here, and they’re downright giddy.” Ramy informs Walter and Sean that Apple is excited, that the company loves the idea of him using FCP.

At this point, Ramy reaches across the country for more help, getting in contact with Zed Saeed, a FCP fellow traveler on the East Coast. Saeed had put Oxygen Media on Final Cut Pro, the first television network of any substance to use the application. When he began working at Oxygen they had two Final Cut Pro systems; when he finished they had 200. Zed in New York, much like Ramy in Los Angeles, saw the future possibilities of Final Cut Pro in film editing. And since he was one of the few people on the East Coast to understand both technical and user needs, Zed had most of the new opportunities to himself. He also became a post-production consultant to Showtime Networks, designing and managing their film-based editing systems using Final Cut Pro.

Zed Zaeed, senior post production coordinator at DigitalFilm Tree.

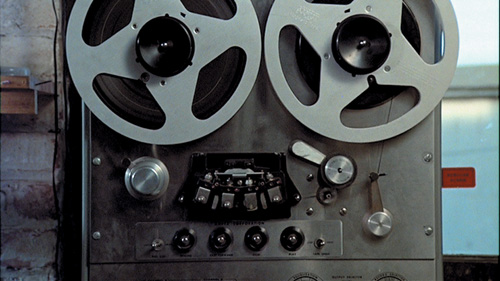

Born and raised in Pakistan, Zed Saeed came to the U.S. in 1983 to attend Hampshire College in western Massachusetts. By 1984, he had won his first Student Emmy Award for his short film Back to School. Of all the Final Cut Pro specialists none might be more excited about Murch using the system than Saeed. “There was nothing I ever wanted to do more than just make films,” he says. “My friends and I, we lived films: we ate film, we made films, we slept films. When I was in college we were obsessed with The Conversation, because as film students we were taught it was the height of sound design. We actually recorded the soundtrack of The Conversation from the videotape to ¼-inch audiotape—just like Harry Caul! We would be in our dorm rooms playing the reel-to-reel, listening to the soundtrack of The Conversation over and over and over again. I mean, that’s how obsessed we were with Walter Murch’s work. And it wasn’t like we thought it was a Coppola thing; we knew it was a Murch thing. We had researched it and found out he had put it together and it was his ideas. I’m not making this up after the fact. You can call my friends up and they’ll tell you, ‘Yeah, yeah, we used to do the reel-to-reel thing all the time.’”

Ramy Katrib and Zed Saeed first met in Las Vegas at NAB, the National Association of Broadcasters annual electronic media trade show. “We had a hysterical time in the hotel room where the DFT guys were all staying,” says Saeed. “Right then and there we both agreed that somehow, some day, I’d have to come out to L.A.”

Harry Caul’s reel-to-reel tape recorder from the film, The Conversation. Zed Saeed: “We would be in our dorm rooms playing the reel-to-reel, listening to the soundtrack of The Conversation.”

After Murch and Cullen return to the Lot to complete K-19, Ramy continues talking to Apple about Cold Mountain and the kind of assistance DFT needs so that it can help Murch and Cullen. “The response was fabulous, giddy, salivating,” says Ramy. “I can point to like four or five different individuals who were giving very positive feedback. It was all positive.”

Murch informs director Anthony Minghella about the possibility of using Final Cut Pro on Cold Mountain. Minghella, who is an Apple user and also savvy about digital editing, begins his own research into Final Cut Pro. In an April 28 email to Murch, he reports on his findings. “I see Soderbergh just made Full Frontal using Final Cut and may do the same for Solaris... there was mention that the system can now make change lists. True?” Minghella is open to Murch using Final Cut Pro, but he also knows enough about editing and digital technology to maintain a healthy skepticism.

MAY 7, 2002—BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA

While Walter completes the sound mix on K-19 at the Saul Zaentz Film Center, Sean wraps up his work in Los Angeles and sees to it that the film negative cutting is underway and going smoothly. In the months since K-19 entered its final finishing stages, vast changes have taken place in the Cold Mountain universe: Tom Cruise, originally cast as Inman, has been replaced by Jude Law, and Nicole Kidman, Cruise’s ex-wife, has been signed to play Inman’s lover, Ada Monroe. Equally far-reaching, the production has shifted from the United States to Romania, where more than 70 percent of the film will be shot. The plan is for Murch to leave for the United Kingdom after a few weeks’ break, then set up the Cold Mountain edit in London while film production gets underway in Bucharest. Then, on May 11, Walter receives word from Anthony Minghella that editing for Cold Mountain will not begin in London as originally planned. Instead, Anthony wants Walter to set up shop closer to the set, in Bucharest.

To: Walter Murch

From: Anthony Minghella

Date: May 11, 2002

Dear friend, a wave to you. I am pretending to examine the script but am, in fact, hostage to issues of schedule, budget, score, etc. The more I learn about Romania, the more I feel that there would be some real wisdom in your being based in Bucharest rather than London. I can’t imagine how I could profit from your work during shooting otherwise, and it looks like John [Seale, director of photography] will be using the lab there. I’m particularly thinking about the Crater sequence at the beginning of the movie and how it will need your help in ensuring we’ve collected the material we’ll need in the cutting room. Where are you? How is your inner being? Your outer one? Love and blessings. Ant.

Walter responds to Anthony with a series of questions: What’s the support system like there? The lab? The telecine? Anthony does not immediately know the answers. “We were already stretching the envelope, but if we were doing the stretching in London, at least we’d be in the orbit of people who knew about these things. But Romania?” asks Walter.

A few weeks later, on May 30, out of the blue, Ramy is asked to join a conference call with some Apple executives. “They said they had weighed the pros and the cons, and they would not engage Cold Mountain, Walter, or any part of our effort,” Ramy says later.

Now Ramy has to call Murch with the bad news: “Walter, I don’t know how to say this, but Apple said we shouldn’t do this, and that they will not be involved at all.”

“Why? Why are they doing this?” Walter wants to know.

“My best explanation is I think the liability is too high for them,” Ramy says. “They think that this project is too big for Final Cut Pro, that Final Cut Pro isn’t ready for something like this. I think some of the people I was talking to don’t appreciate who you are and what you represent to the community. Some of them weren’t the same people who had been enthusiastic, who did appreciate it.”

“Well, what if I still want to do it,” Walter asks firmly, “in spite of Apple? What if I still want to do this?”

There was such forcefulness in his voice that Ramy responds without hesitation. “We’re there! We’ll go with or without Apple.”

“There was no fear in the fact that Apple wasn’t going to go,” Ramy says late one night two years later, sitting at his desk across from Zed Saeed. “It was the strength of his voice, the way he said it. To me, it was just certain. There was nothing that I had to talk about to my partners. We were going to go. That’s when it started to settle in that we were going to be on a long ride—that this was going to change our lives.”

Zed jumps in, as is his wont, finishing Ramy’s thought with exuberance and passion. “This is Walter Murch, man, who’s seen action on Apocalypse Now! He’s asking us to jump into the fire with him. Hell, yes! What are we going to say, ‘Sorry, Walter...’?”

Adds Ramy, “We couldn’t say, ‘Well, if Apple’s not going, I think we’ll pass.’”

“We’re there,” he says softly, reliving the moment.

The day after the conversation in which Ramy and Walter tentatively decide to proceed with plans to edit Cold Mountain on Final Cut Pro, Walter sends him this email: “Dear Ramy: Good talking to you yesterday, and I am hopeful it will all work out. Any chance of getting a phone number for Steve Jobs? Thanks, Walter M.”