Chapter 7. The Flow of It

The eye on the pole.

Three months into production, Murch is working 12 to 14 hours a day, six days out of every seven. But he faithfully takes an eight-mile run once a week, on Sunday, his one day off. He throws a coin onto a city map, then heads off in that direction from the hotel. Bucharest is a wonderfully strange city, with much to take in, so he brings along two tools of the trade: a digital still camera and a microcassette audio recorder. Today, a fine fall Sunday, is particularly plentiful:

October 13, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Good Run out Plevnei Boulevard to the pedestrian overpass across the RR tracks.

Main entrance of Cotroceni Palace, passing it just now.

Took a picture of an eye on a telephone post—beautiful.

An older woman in an orange overcoat: talked to me about “sports” as I ran by on Plevnei.

On Giuleshti—why does this all feel familiar in some strange way? The northern part of Manhattan, southern part of the Bronx when I was growing up.

Grand Overpass: you can drive onto it from Giuleshti, but how do you get off it onto Grivitsei? It seemed like you could from the street map I just passed.

The halfway point is the little pizza place on Grivitsei that they were painting up about a month ago.

A wedding at St. George’s: with an accordion player outside welcoming them in.

Next day, it’s back to work upstairs at Kodak Cinelabs. At this stage in the filmmaking process Murch organizes his editing activities into what he calls “groups.” He defines a group as the amount of film he can “put on my plate at any one time.” Ideally, it is also a sequence, a succession of connected scenes.

Earlier, Murch broke the script down into numbered sequences before shooting began, based on his feeling for the dramatic “clustering” of scenes. For example, group 16, as Murch catalogs it, consists of part of sequence 18 and part of sequence 19, four scenes in all: Inman and Reverend Veasey leaving the river where they hid from the Home Guard; the two of them coming upon Junior (Giovanni Ribisi) and a dead bull; helping Junior dispose of the bull; Junior inviting them back to his place; and the men being greeted by the women at the cabin. In the screenplay these are part of scene 93 and all of scenes 94, 95, and 96. Murch’s one-line description for the sequence is: “Inman & V: find saw, meet Junior, ‘There’ll be tang.’” There are a total of 45 sequences in the film, and they consist of 213 scenes.

October 14, 2002, Murch’s Journal

If I finish Group 12 today, God willing then I will have cut 12½ minutes in three working days from start to finish, which would be 25 minutes a six-day week. If I could maintain that... I would be done cutting the film three days after they finish shooting... Inshallah. 01/14/03: I did not even come close. 02/14/03: I hope to be all finished by Monday Feb 17th.

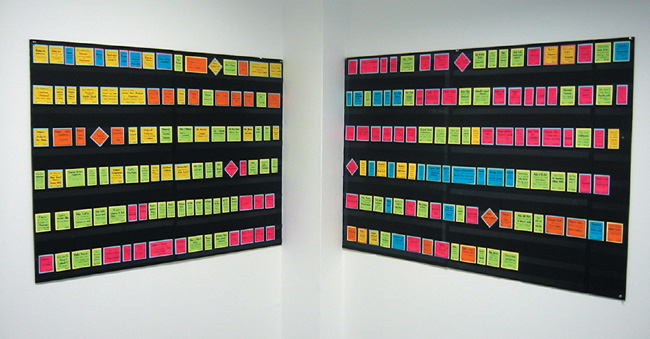

During production, selecting a group to work on is simply a function of what sections are available in their entirety—what’s been shot. A scene that has been shot has its card marked with a yellow tag, so when Murch looks over his scene boards and spots an adjacent set, all with yellow tags, he’ll designate that as a group. But group 15, for example, was made up of four disconnected scenes: 56–Rooster attacks Ada; 67–Ada looks into the well; 86–Ruby and Ada build a fence; and the main part of 93–Veasey finds a saw. A group averages 15,000 feet of film dailies, or three hours. By working in these hunks, Murch’s notes can be “proportional and useful,” he says. “Any smaller and I’d be too picky and detailed; any longer and I’d be overwhelmed.”

Murch views each shot from the group, making a second set of notes about what he sees. He made the first set of notes during dailies, the day after shooting. Murch puts notes into the logbook on his laptop. It’s a record-keeping system set up in FileMaker Pro that he designed for this purpose, first used on The Unbearable Lightness of Being. The single record (shown on the next page) contains all the editing information for one camera take: a wide shot in group 16/sequence 18—Inman, Veasey, and Junior stand in the creek; Inman and Veasey help Junior with the dead bull.

Murch’s first set of notes from dailies screenings are simple, descriptive, and record his immediate emotional reactions—all that’s really required at this point in the process. The notes from his second viewing will be more detailed and analytical, go deeper, and record the footage counts for each of the 20 “beats,” or dramatic moments, that Murch feels in this single shot. “The first set of notes are a lover’s first impression of the beloved,” Murch says later. “The second set are a surgeon’s notes before making the first incision.”

Murch makes these scene cards by hand. When a group is marked with a yellow tag, it means the scenes have been shot and they’re ready for editing.

The same scene as written in the screenplay.

As he is writing his “surgeon’s” notes, Murch hasn’t yet looked at Minghella’s shooting comments, which come with script supervisor Dianne Dreyer’s notes as well. Interestingly, there is no distinction between Minghella’s and Dreyer’s comments. When Murch finally toggles FileMaker to reveal Minghella/Dreyer’s comments for this particular take, he finds simply, “With Hallelujah.” The note means there was an extra line recorded for this take: Veasey’s exclamation as he runs into the woods to defecate.

Work on a group normally takes three days. On the first day, Murch screens and takes notes. If a group consists of three hours of film (a typical amount), it will take Murch nine hours to watch it, stopping as necessary to make notes. On the second day, he’ll use FCP to assemble the material into scenes—the first time the material has been joined together editorially. He will do this with the sound turned off, even if it is a dialogue scene, treating everything as if it were a silent movie. On his third day with a group, Murch turns on the sound and refines his work of the previous day—trimming beginnings and endings of shots, moving dialogue around, overlapping picture and sound. He is finding the film’s rhythm and getting shots to work more precisely with each other. Larger structural issues that may arise are noted but left undone. It’s not yet time for those kinds of decisions. As Murch describes it, he “doesn’t know enough yet, and I’m only the editor.” So he works with “eyes half-closed, not expressing opinions unreservedly.” Until the first assembly is completed, every scene gets the benefit of the doubt.

Working six-day weeks, Murch can complete two groups a week. The amount of film shot on Cold Mountain already surpasses 300,000 feet, or 55 hours. Having passed the halfway point in the shooting schedule, Murch is rethinking his note-taking system, pondering how best to keep up with the regular flood of footage, yet adequately annotate so he has a useful reference.

October 19, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Finished group 14 sound and revisions and got 4,000 feet into notes on 16 (12,000 feet) so a third of the way. Also caught up on dailies looked at four reels from day 61. How can I speed up the note-taking process? I have tried doing selects only... “Be a star in three scenes and adequate in everything else,” as John Ford said. The trick is to define adequate.

Back in the U.S., word that Murch is using Final Cut Pro to edit Cold Mountain begins to get around the filmmaking community. A technology reporter for The Hollywood Reporter, the entertainment industry trade paper, inquires about doing a story. Walter has an exchange of emails with Ramy at DigitalFilm Tree about whether it’s a good idea to be interviewed for the story while technical issues are still being worked out. How should he explain the “known unknowns”—especially the uncertainties of having reliable change lists and the audio export protocol needed for sound editing? He doesn’t want to come out with anything that might embarrass Apple.

The two-column list from Murch’s logbook with some of the takes for scenes 93 and 94, including shot #459-Bi7.

Murch’s second viewing notes for shot #459-Bi7.

“I don’t want Apple to have a fit,” he writes to Ramy. “On the other hand I don’t want Miramax to have a fit either. The truth is, it will all work out, but it is a delicate political situation.”

Ramy answers by encouraging Walter to go forward with the interview; DFT will be happy to supply The Hollywood Reporter with any background or technical information for the story. In this same email, perhaps of more immediate significance, Ramy also writes about new developments with change lists: “We are providing Apple with workflow notes for Loran Kary who is leading the creation of Cinema Tools’ change list functionality due out around April... it is public knowledge that Apple recently purchased EMagic, a large European audio software/hardware company. Clearly Apple is ‘going in the direction’ of professional software/hardware.” Since its inception, Apple has branded itself as making computers “for the rest of us”—suggesting that it focuses primarily on serving consumers. But as more highly regarded professionals like Murch pick up applications such as Final Cut Pro and run with them, Apple becomes an even stronger force in the creative community, where it has always been the favored platform.

The news about positive developments with change lists for Final Cut Pro is soon confirmed when Ramy gets an eyewitness demonstration at Apple headquarters, which Walter notes in his journal:

October 22, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Great email from Ramy: “I just saw a change list print out. It looks really good. In short, change lists will not be an issue. Loran did well, he surprised us. Just wanted to let you know. Please keep this sealed.” That is great, great news—another ogre waiting for us down the hall just disappeared. Inshallah.

Murch decides to do the interview with The Hollywood Reporter.

By this time, Murch’s assistants are going strong on their Final Cut Pro systems, cutting away on their scenes. In a follow-up email to The Hollywood Reporter writer, Sheigh Crabtree, Murch proudly explains how the apprentice editors are working: “G4 laptops (even an old clamshell iBook) can become satellite stations, not linked to FibreChannel.” Murch is saying that Final Cut can be configured to run more simply on laptops than when it is networked among several workstations and must use an external viewing monitor, as it is configured for his edit room. “You download the selected media to each laptop, which is equipped with just FCP (no Aurora card needed if no NTSC monitor).” The assistants can then export their edited scenes back to the main system—as sequence information only—“where it is relinked to the media on the FibreChannel. If you include these laptops, we have seven stations working on the film.”

November 2, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Sean and Dei’s scenes are done, recut, and in the film. They turned out well and just needed a little “Murching.” We may catch up some time. Saw Walter’s scenes in progress. There is something very considerate and precise about his work and the way he is doing it. God bless. Ilinca and Susanna’s scenes yet to come: Wuthering Heights and “Cut my hair once.” Five assistants learning to edit by actually doing it, and then showing the material to me, getting notes, and revising. What other system would have made doing this so easy?

Having passed the two-thirds point in the shooting schedule, Murch begins to share a common concern among crew, cast, and producers: Will Minghella finish filming on time, which is scheduled for December 7? Going overtime on a motion picture can cause all sorts of problems. Just being permitted to film for extra days can be a major struggle between director and studio. It may even be forbidden by contract or by the completion guaranty company that issues the insurance bond against just such a contingency.

November 6, 2002, Murch’s Journal

In any ten-day period Ant has shot 20 scenes, sometimes 19, once 18. EXCEPT for the first ten days, when he shot seven, and days 61-70, when he shot 11 (Chain gang escaping from Brown and killed). Otherwise it is 20, 18, 19, 20, 20, 19. If he can keep up that rate, he needs 35 more shooting days, and he has 28. So seven is the magic number.

Film production can be exhausting.

Murch determines from Dianne Dreyer’s reports that Minghella begins picking up the pace: He writes in he journal: “In the last ten days: Ant has shot 23 scenes, including all of the Sara stuff, or 2.3 scenes a day. He has 60 scenes to shoot in 26 days, which is 2.3 scenes a day. So maintaining the current pace, he can finish on time. Congratulations!”

Later in November Murch has dinner with Steve Andrews, the first assistant director. (Andrews, Murch, and Minghella all worked together in their same capacities on The Talented Mr. Ripley and The English Patient.) As first assistant director, Andrews is primarily responsible for keeping director and crew on schedule, and for getting each day’s designated script pages shot in the time allotted—“making the day.” Murch and Andrews discuss what this takes, and what can drag it down.

“Will we finish on time?” Andrews asks.

Murch tells him they will if the rate of 2.3 scenes a day established over the last ten days continues.

“Do you have enough time to cut the film?” Andrews asks.

“It is about the same as Ripley,” Murch responds, “with a little more wiggle room because of intercutting the two stories. The weak spot will probably be from the end of the battle until Inman gets on the road and Ruby appears.” There will be tremendous pressure to resolve this as soon as possible, he says.

Film dailies being processed in the “bath” at Kodak Bucharest.

In addition to being a beehive of activity, Murch’s editing room has now become a preferred destination for anyone who visits Cold Mountain in Romania, according to producer Albert Berger. “Normally you’d just high-tail it to the set, but this was a must-stop, to go to his domain. He was like a mad scientist up there doing all these experiments.” Producers, movie executives, press, friends of the cast and crew—even Cold Mountain author Charles Frazier—all climb the stairs to the second floor of Kodak Cinelab. They know Murch’s credits and awards, of course, but are drawn because they hear that Murch is up to something special using the Final Cut Pro system.

“Normally you’d just high-tail it to the set, but this was a must-stop, to go to Walter’s domain.”

November 11, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Reviewed Sean’s new scene: very good, just one or two changes... and also Dei’s scene, same thing—the scene at the door with Sally and the girls he did very well. Charles Frazier and wife Katherine came to visit—very nice, spent an hour or so with them, talking about the film and the process.

Gave Ilinca her scene.

Having assistants able to cut scenes is one aspect of Final Cut Pro’s potential for egalitarianism. Ilinca Nanoveanu, the Romanian apprentice editor, cuts the scene of Ada reading Wuthering Heights to Ruby, and she later mentions this to Anthony at a crew and cast party.

“I heard you liked my scene,” she says.

“What?” Anthony says, astonished.

As young Walter later tells the story: “Dad sat us down at breakfast. No one was supposed to know that we were working on scenes. Ilinca came into our edit room later and cried her eyes out because she thought she had done something terrible. I told her to go in and tell Dad. ‘You’ll feel better,’ I said. She came back in tears.”

Later Murch explains to Minghella that he is giving the assistants rare editing experience, something Final Cut alone makes possible. He makes it clear that he reviews and re-edits those scenes as necessary. Minghella supports the experiment—another testament to his faith in Murch.

December 10, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Ilinca upset that she told Anthony that she cut the Heathcliff scene. Tears and self-recrimination. I console her, but tell her to take the lesson to heart. But not so much to heart that it becomes a black hole.

Despite the contretemps, Murch later looks back on it proudly. “Seeing Ilinca cut that scene makes Final Cut Pro worth the price of admission,” he says. “It’s the first time the assistants had access to the editing experience on a film like this, where they can work with professionally shot material and be able to bounce their work off me. Something like that just hasn’t been economically or logistically possible before FCP.”

The time is soon approaching when production will end, the editing crew will move to London to finish the film, and the sound conversion issue becomes more urgent. An email from Ramy gives Murch hope for a new solution. Ramy proposes a working relationship between Murch and Mark Gilbert, an audio software developer with the London firm, Gallery. “There is the potential of him playing a part in addressing ‘unknown sound post’ issues facing us,” Ramy writes to Walter on November 19, 2002.

Like DFT’s friend, Brooks Harris, Mark Gilbert develops software solutions for difficult audio-transfer problems. As it happens, Gilbert has worked for George Lucas on Star Wars Episode I and met Murch, who was visiting a dialogue recording session for Episode I at Abbey Road Studios in London. Gallery has a pioneering OMF technology called MetaFlow, which takes 24-bit film sound recorded on location, converts it into 16-bit files readable by an Avid, and then exports these edited soundtracks into ProTools for refined sound editing. Movies such as Die Another Day, The Matrix, and Jersey Girl all used MetaFlow. Gilbert tells Ramy he’s “really keen” to see if he can adapt MetaFlow to help Walter with Final Cut.

Once again the question of Apple’s operating systems arises. Ramy engages Murch in an email dialogue about upgrading all of Murch’s Final Cut Pro systems from Mac OS 9.2 to Mac OS X (aka “System 10”). By making this change Murch could step onto Apple’s chosen playing field, and be in a better position to receive official support. Two companies whose gear Murch uses are already preparing for the new OS. Aurora, which makes his Igniter video digitizing card, is coming out with a beta version for OS X. Rorke, which makes his shared area network (SAN) media storage system, is also unveiling an OS X beta test version of its networking software for the 1.2 terabyte hard drive array. Murch is game for converting to OS X when he moves to London. Two days later Ramy shares this information with Bill Hudson at Apple: “There are some important issues that need to be addressed now, including their [Cold Mountain] migration to OS X. I am assuming this is something everyone will want. In my last communication with Walter, he was open to migrating to OS X if done properly and safely. So let’s strategize our next step here as they will be going to London and start post soon. Call me at the next opportunity as we want to be on the ball.”

Two weeks later Hudson replies in an email to Ramy that converting Cold Mountain to Mac OS X, “scares the hell out of me—especially since they are working so well now with what they have.” Separately, Brian Meaney concurs: “I think moving them to OS X will be very hard right now without a known SAN solution.” Apple is once again caught in a dilemma. Getting Murch on Mac OS X would allow the company to be more on-the-record helpful with software solutions and general troubleshooting. But changing operating systems in the middle of a film does not seem wise. It could put the film at risk. Apple advises to stand pat. Cautious as that may sound, Apple has Murch and Cold Mountain’s best interests at heart.

On Thanksgiving Day Ramy receives bad, but not quite terminal, news from Mark Gilbert in London about his MetaFlow program for sound export: Gilbert may not be able to solve Murch’s audio export problem after all. “FCP can only do embedded OMF,” Gilbert tells Ramy, “rather than compositions only. This seems to be what Walter is asking for. In fact, that’s not something we will be able to assist with, I am afraid. I will look into other ways of getting the events list out of FCP. I know there is a hack to do this which might be exploitable.” Should Murch and Cullen fail to get a solution from either Mark Gilbert or Brooks Harris to overcome Final Cut Pro’s sound export limitations, they will be forced to create their own multi-step workaround—an extra task they hoped to avoid but are ready to do if necessary.

November 23, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Party for “Thanksgiving” here in Brashov—thrown by Nicole, Jude, Renée. Jack White and the White Stripes performed (he plays the character, Georgia). Very loud but good—but I couldn’t take too much of it. I sat and talked to Ilinca at the coffee bar and Jude came over, and Ilinca was very happy to meet and be introduced to him. He talked about his work on this film, and how meeting this character has been a revelation to him, has forced him to be a better person.

There is one month left until production wraps in Romania. Having cut together more and more film, Murch begins to find Cold Mountain’s rhythms and patterns. He senses how some separate scenes might work better intermingled.

November 16, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Finished Swanger killing and torture, group 20, turned out well, I think—interesting sounds (breathing and squeaks)—and good surprising intercuts of Ada and Ruby after the shotgun blast goes off. I thought it would be one intercut, but it turned out to be three: “what’s that” :: then return to Esco killing and Sally collapse :: back to Ruby running off leaving Ada :: move in on Teague looking and listening to the struggle :: back to Ada running off.

Four months later, when he edits this scene again in London, Murch will write in his journal, “Now it is just, ‘what’s that?’ without either of them running off.”

The dogs of time keep nipping at his heels. On Sunday, November 17, Murch writes about his progress putting the first assembly together: “Today I have been cutting for three and a half months and am just coming up to three hours, which is not quite fifteen minutes a week. How to improve, move faster, keep the work at a high level?”

A makeshift sound stage has been constructed in an abandoned helicopter factory up in the mountains. This is where the first camera unit will film crucial scenes between Inman and Ada by the campfire, their subsequent lovemaking, and the forest scene where Teague and his gang find deserters Pangle and Stobrod and shoot them.

Weather permitting, a day must also be found to film the exterior scene of Inman’s death—the final scene in the film except for the coda, which was shot months ago at the height of summer.

At this point there are often more than three hours of dailies to be screened and logged each day, which eats up time that would otherwise be spent assembling material. Aggie flies in from London the afternoon of December 6 and hangs out in the editing rooms until Murch finishes screening selects at 10 p.m. This week 56,000 feet of film dailies are printed, more than double the average week’s volume.

Any equipment not immediately necessary to the task at hand is boxed up to be shipped in advance to London. The edit rooms begin to have a transient look to them.

The plan is now to extend the shooting an extra six days past the original wrap, with Saturday, December 14, being the final cutoff. Anything not done by that date will not be shot.

Ilinca marks sync on the last Cold Mountain daily roll using “the electro-muscular-mechanical process,” as Murch calls it.

On December 9, Aggie flies back to London after a final weekend in Bucharest, with a last celebratory dinner for the whole editorial crew on Saturday.

More footage is shot in the final six days than in any other week of production—59,000 feet, almost 10 percent of the entire amount of workprint over the 113 shooting days.

The last take on the last day of filming (setup number 954) is Georgia’s point-of-view of Teague shooting Pangle and Stobrod. And with that gunshot, production comes to an end.

Activity at Cinelabs continues for another day, however. Saturday’s material has to be developed and printed, and then screened on Sunday before the actors and crew can be released. If the film has been scratched or damaged, the scene must be redone. The lab is kept open and busy over the weekend.

December 15, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Finished looking at dailies from the last day’s filming. All ok. 4,900 records in the Log Book. 597,000 feet of dailies. 33,000 in the last three days. There are some MIA’s I have to catch up on, but that’s all... Congratulations to everybody... Packing UP!

On Monday, Murch and Cullen, and Cullen’s wife Juliette and baby Ora, leave Romania for London to set up the editing rooms at Minghella’s Old Chapel Studios. Young Walter, Dei Reynolds, and the Romanian apprentices, Mihai and Ilinca, stay on to finish the final boxing up of equipment and film.

December 16, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Flying out of Bucharest to London with most of the crew—Anthony sitting across the aisle, Ian in front of me, Sean and Juliette and Ora up the by the bulkhead. Farewell Romania. You were good to us and we thank you.

Arrived safely at PH. Aggie was home, and we spent a lovely afternoon evening.

When British film directors choose to live and work in London rather than migrate to Hollywood, they are saying something about who they are and the kinds of films they want to make—and that’s true for Anthony Minghella, who was born on the Isle of Wight. There is an active moviemaking community in the United Kingdom, and some wonderfully original and independent voices. Think of Mike Leigh, Mike Newell, Stephen Frears, and Neil Jordan. Normally they work on smallish budget films with backing from various U.K. government funds and tax-benefit programs; only rarely do American studios support their work. So when an Academy Award-winning director decides to stay home and not relocate to Los Angeles, that’s news—especially when his current movie is the high-profile Cold Mountain, financed and distributed by Miramax Films. Recognizing this, along with Minghella’s vision, leadership, and ambitious ideas for the industry, the British Film Council appoints him chairman of the prestigious British Film Institute at the end of 2002.

Minghella will complete Cold Mountain working from the London production office of Mirage Enterprises, a company he runs with his partner, Sydney Pollack. Mirage is located in a former Baptist chapel near Hampstead Heath in North London; it was previously a studio space for rock-and-roll photographer Gered Mankowitz. The Old Chapel studio, as it’s called, is a convenient ten-minute walk from Minghella’s house. Murch’s edit suite will be located on the second floor in four small, cozy rooms. Downstairs in his office, Minghella will have his own Final Cut Pro edit station. Like the other four stations upstairs, it will be linked to the Rorke RAID system over a FibreChannel.

The Old Chapel Studio near Hampstead Heath in London.

December 18, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Meeting with Anthony to discuss preliminary scheduling. I said I wouldn’t be done at least before the 27th of January, God willing.

Half of the Cold Mountain Romanian edit rooms were disassembled two weeks prior, crated up, and shipped to London so Walter could arrive and continue working unabated.

December 20, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Trying to do notes on 30 and did some, but felt exhausted, hopeless. Rest of our equipment didn’t arrive today and now will sit in storage until Monday the 6th.

The holidays are here, time for a break: two weeks off. Fortunately for Murch, he is well acquainted with London and enjoys living and working here. In the mid-1980s, not far from the Old Chapel, he oversaw work done by the Jim Henson Studios for Return to Oz. He edited Julia for director Fred Zinneman in London. His wife, Aggie, is English, and they have a cottage in Primrose Hill, a pleasant 20-minute walk from the Mirage offices.

It’s been five months since Murch passed through London on his way to Romania to begin work on Cold Mountain. The film is now scheduled to open in one year’s time, on Christmas Day, 2003. In an ideal world, after this holiday hiatus Murch would be screening the first assembly for Minghella. Instead, he estimates he’s at least four weeks behind schedule. Standing down now for two weeks provides much needed rest, recuperation, and resettling for him and his assistants. But this interval is like intermittent slumber with troubled dreams of big things left undone. After the break, when Murch arrives at the Old Chapel to resume work, it’s the middle of winter and threatening to snow.

January 6, 2003, Murch’s Journal

I am grumpy and nervous, scared, tired, disoriented. Walk to the Chapel and have a meeting with Sean, Walter, Dei—what needs to get done this week.

Is Final Cut Pro to blame for Murch being behind? Would the edit schedule have been any different using Avid? Recall that Murch did not start assembling footage until the end of July, two weeks later than he originally hoped. There were delays getting the conventional editing equipment through Romanian customs: benches, rewinds, bins. A lot of time and energy was spent early on with Final Cut Pro issues: getting audio conversions figured out, refining the workflow, and communicating with DigitalFilm Tree. All that effort, to some undetermined extent, cost precious time.

On the other hand, FCP never seized up. Ingenious workarounds kept everything running. It may have simply been the deluge of film footage that weighed down the schedule, on top of not having second assistant Dei Reynolds on board until the end of July.

It snowed all that week of January 6 in London—the heaviest in a decade. By Friday the snow is gone, Walter’s edit room is fully set up, and his spirits lift.

January 9, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Harvey W visits the Chapel and we screen some material for him: Junior’s, Sara’s, Stobrod, and Ruby. He likes it, laughs at the right places.

Once again the journal is replete with footage calculations, schedule projections for the remaining groups, a new three act division of the entire film, and a measurement of the walking distance from Murch’s cottage to the edit rooms at the Old Chapel: 1,280 paces. And a meditation: “May I ask your help to find out what the best path is to get the assembly together, in the best shape.”

The pace picks up, from a brisk walk to a healthy jog.

January 13, 2003, Murch’s Journal

It feels good to be cutting again: like grandma playing her piano: “If I didn’t do this every day, I would have died long ago,” she said to me once, aged 97, as she was pounding it out in the front room of her house. There is something about it, the music of it, which is enhancing.

Everything about the edit is now directed at the intermediate finish line of completing the first assembly. Only when Murch has all the scenes laid out according to the script can Minghella re-engage with the work and make his transition from director shooting to director editing. Once a first assembly is screened, the director can truly fathom what he has to work with and start getting the film down to a releasable length. Minghella and Murch will start searching for the movie that lies beneath the surface, like Michelangelo, finding the figure that exists within the marble, waiting to be revealed.

Minghella on the stairway at the Old Chapel.

As Walter sees it, the break a director is forced to take between filming and editing is a good thing, a necessary transition. Film directors should come down off the emotional roller coaster of shooting a movie before they enter the quiet, deliberative environment of the editing room. From production’s white-hot, highly social milieu of a large crew and top-notch cast, Minghella now joins Murch where a quieter, cooler, and more dispassionate viewpoint prevails. A director must now be prepared to judge a shot for what it is on the screen, not for particular events or emotions involved in filming it. Associations recalled from that particular day on location, positive or negative, are memories to be left behind. Such withdrawal takes time. The further the director distances himself from the shooting, the more helpful he will be in the editing room. On Julia, the 1977 film with Jane Fonda and Vanessa Redgrave that Murch edited, 70 year-old director Fred Zinneman went off to the Alps to scale some mountains, to put himself in life-threatening situations where he had to forget about shooting. For Minghella, a director who relishes the editing process and feels completely at home inside the edit room, coming down off that mountain is a good thing. But the first assembly of Cold Mountain is not yet ready. It is a matter of professional pride for editors to be done with the assembly as quickly as possible after shooting—usually two weeks—and Murch feels guilty that this is not the case. He hopes Minghella will be sympathetic to the facts of the schedule.

January 16, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Answer from Anthony who was calming—talked about being finished when I am finished. “I know you’ll be ready with the assembly as soon as you can be, and that’s the beginning and end of the matter. If there’s anything I can do to help then let me know. I meet with Miramax and the producers on Friday and will explain the delay and why there is one. Obviously, we need to get going on a cut, but the failings are mine, I think, rather than yours.”

However patient he might be, Minghella is champing to get underway with the editing. He’s spent the past two weeks getting familiar with Final Cut Pro and he wants to put it to work reviewing scenes on his own, thinking about changes, making notes, and engaging with Murch in the process. So now, at the end of January 2003, not wanting to keep Minghella waiting any longer, Murch screens a nearly completed first assembly that runs just under four hours. Murch, Minghella, his wife Carolyn and son Max, and Cassius Matthias, one of the Mirage staff producers, gather in Walter’s edit room on a Saturday afternoon. Murch turns down the dimmer, the track lights go out, and he hits play. The Panasonic 50-inch plasma display lights up and the film begins. A few moments into the battle scene there’s a problem: “It kept freezing,” Murch writes later, “something about the complexity of layered and filtered sound when the film is that long... it was frustrating, but ultimately Ant was generous about the situation. We will reconvene on Monday afternoon.”

Sean and Walter stay late to figure out the nature of the problem. They can see that the playhead on the Final Cut timeline acts fragile and sticky even when they reduce the amount of media they ask FCP to play from 2½ hours to half an hour. An important viewing for the director was cancelled, and the solution was not yet in sight.

January 25, 2003, Murch’s Journal

After the screening, walking home, I feel as if my head is coming unscrewed.

The following day Murch shares his frustration with Ramy in an email with a subject line, Difficulties: “You can imagine the disappointment all around, particularly for me. The editor has only one chance to show the director his version of the film, and this is now gone.”

Over the weekend, Murch and Cullen discover Final Cut’s problem: the software can’t handle the quantity of audio equalization filtering that Murch had added to the soundtracks. He was using multiple filters to improve the sound of some sections of dialogue. They were playing in real time, as opposed to being rendered, or permanently embedded in the saved file. If more of these audio effects are rendered ahead of time, it’s easier for FCP to play long sequences. A bug in FCP 3.0 overestimated the complexity of audio filtering, acting like a software traffic cop telling it, “Slow down, slippery road ahead,” when in fact the road was clear and dry. Murch learns that FCP can be ungainly when it moves, copies, and renders large amount of digitized footage. It all takes longer than it would in Avid. The frustration level rises. “How will the schedule work out with so much still to edit?” Murch writes a few days later in his journal. “God bless this situation and may it resolve itself happily and creatively.”

The second attempt to screen the four-hour assembly using newly rendered audio material goes fine. Not yet being the entire assembly, it ends with Inman cresting the mountain and seeing the town of Cold Mountain below.

January 27, 2003, Murch’s Journal

The motto on Tower Cottage [an old house Murch passes every day on his way to work]: is “Strength and Patience”—Fortis et Patiens. Let that be your motto now. Successfully screened the film twice—once for me to see that it all went smoothly, once for Anthony and me. We finished about nine thirty. Well done! You got through it—at least this part.

There is much to think about in that four-hour assembly, but firm opinions have still to be put on hold until the whole film can be seen in one piece from beginning to end.

Cold Mountain sound supervisor, Eddy Joseph, has worked on sound for major motion pictures for over 25 years.

Plans are made to staff up the sound editing crew. Walter and Anthony meet with Eddy Joseph, the supervising sound editor, a 50-something Englishman who’s worked in that capacity on Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, many of director Alan Parker’s movies, and has 25 years experience with sound and movies. In addition to editing sound himself, Eddy will manage a six-man crew of sound editors and assistants who each specialize in various sub-fields: dialogue, ADR (automatic dialogue replacement), atmospheres (like birds chirping, wind blowing), “hard” effects (gunshots, horses, etc.), and Foley (footsteps and character movement). He’ll be responsible for bringing all the sound elements together in the sound mixing theater, first in temporary mixes for preview screenings, and at the end, for a final sound mix that Murch will manage, and co-mix.

Anthony explains to Eddy how he and Murch will be making “enormous changes at the last minute,” which can be a nightmare for the sound department. Anthony likes to work on films until the very last possible moment, tweaking the cuts, replacing lines of dialogue, dropping or adding scenes, or trying a new music cue. It comes from his live theater experience and a writer’s never-ending need to revise. It’s difficult for Minghella to see the enterprise as really ever done, finished and impervious, like cured concrete. Murch shares this same drive to find perfection. Eddy says he is ready to be flexible and “pro-actively creative.” There is one potential hitch: Eddy says he doesn’t really like the ProTools sound editing system. He doesn’t have that much personal experience with it, but is “willing to give it a go.”

February 13, 2003, Murch’s Journal

I finished the campfire killing grounds scene—whew. But that puts me behind the eight ball for the remaining scenes with Inman and Ada. Guidance and wisdom and assistance, please...

The day before Murch completes the full first assembly, he steps back for a moment and asks rhetorically, “Why are we screening the film two months after the end of principal photography? Because the load of film—600,000 feet—is just beyond what I can process and keep up with working six days a week. It means that the slightest wrinkle sets me over the edge and I lose time that I cannot retrieve.”

Murch makes a list of what might have kept things on schedule, and what could be done differently next time.

2. Anthony make selections and give me detailed notes

3. Hire an additional editor to work with me

4. Hire a different editor, one who works faster than I do

5. Not have delays at the beginning that made it impossible for me to start editing until two weeks after start of shooting

6. Not move into a facility (the Chapel) that had never had a film edited in it (also applies to Kodak)

7. Not move location until the first assembly is finished

8. Have a “Man in Havana” here in London setting things up before we came back

What may appear on the surface to be an aggressive, even cold-hearted attitude, is really a matter of feeling bad about being late, Murch admits later. “Editors often strike a macho posture,” he says, “proving to their directors how good they are by delivering a first assembly as soon as one week after production ends.”

Murch will screen the entire first assembly on February 18. He refers to this volume reduction—compiling the first assembly from all the raw footage—as “the crush ratio,” a term in winemaking that measures the first pressing against the original volume of picked grapes. A second pressing will get the first assembly down to a release print. Murch already looks beyond the first crush to the second pressing: getting a five hour-plus assembly to a releasable length.

February 15, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Crush ratio on CM is 22:1.On EP it was 11:1. Julia had a CR of 12, but only shot 180,000 feet. Then there is the second pressing, which is how much of the assembly do you throw away? On Ripley it was 55%. On Julia it was 30%. On EP it was 40%. On K-19 it was 43% ¶ 03/15/03 on Apocalypse the crush ratio was 11% and the second pressing was 55%

February 16, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Finished this assembly 11pm Sunday night. Five hours four minutes seventeen seconds. Congratulations! Exactly two months since we returned to England, and seven months since the first day’s dailies.

One of the limitations of Final Cut 3.0 is an arbitrary time cutoff: no sequence can be longer than four hours. So, as with old-fashioned road-show movies of the fifties, the Cold Mountain first assembly must be shown in two parts, with an intermission.

February 18, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Beautiful sunny frosty day and I’m off to screen the film.

Successful screening of the film, no technical glitches—in two 2.5-hour parts. First impressions: It is long and has an eccentric beginning. The film hits the tracks when Ruby arrives (and Veasey soon after). Solve the beginning, cut it down but keep the two stories balanced, find the most efficient path.

Taking tomorrow off...

There is nothing more important to humanity’s physical, psychic, social, and political survival and well-being than the conversion to hydrogen fuel.

A new phase of editing begins—refining the story, clarifying the emotions, making the first steps at reducing the first assembly to an acceptable running time. The orientation over the last six months has been one of accumulation, a building-up of material. Now the engines are suddenly thrown into full reverse. The enterprise will head in the opposite direction, shedding material as expeditiously as possible. Murch may be more than five weeks behind schedule, but before he turns up the speed it’s time to make inquiries to Apple in Cupertino about acquiring Final Cut Pro version 4.0. Among other features, the new software release is rumored to include support for making reliable change lists and a function for exporting edited audio files to ProTools for further sound editing. These two functions could help Murch make up for time lost, or at least prevent further delays.

FEBRUARY 24, 2003—LONDON

Murch sends Brian Meaney, Apple’s Final Cut Pro product designer, an email update on progress with Cold Mountain and the successful first assembly screening. “Anthony Minghella said that he had ‘absolute confidence’ in the fidelity of the FCP image compared to what he remembers from the projected 35mm film dailies, and would be delighted to show the film to Miramax on an FCP output.” Murch mentions the “teething problems” he experienced with slowed-down playback caused by the audio filters. Then he invites Meaney to come visit the edit room in London, in part so he can discuss “a running list of suggestions for operational improvements in FCP as well as features in the present system that I think are particularly successful. Toward the end of March we would like to begin the process of conforming the 35mm workprint,” that is, preparing a version in film that mirrors his FCP cut—a projectable film print for theater screenings. Then Murch pops the question: “To that end, when a beta of the next version of FCP is available, we would love to be able to test-drive it on the one CM workstation that we have already converted to OS X.” Murch encourages continued dialogue between Apple and DigitalFilm Tree regarding OMF sound export. He then concludes, writing about the whole Cold Mountain/Final Cut Pro endeavor: “Congratulations to everyone on the FCP team whose efforts made this achievement not only possible but eminently pleasurable.”

Two days later Meaney responds to Murch. It’s a friendly, positive email but it needs some decoding: “Thanks for the good word! I’m glad things are moving along so well with your project... And most definitely when a new version of FCP is available, I would be very interested in getting your thoughts.” Not exactly a commitment for a tangible piece of software Murch hoped to get, but Meaney does offer to send Walter the beta copy of Cinema Tools, “which has preliminary change list support inside of it.”

This is very good news. Murch and Cullen will at least get one piece they need to finish the puzzle: the change list function. Revisions to the picture that Murch makes will be accurately and efficiently transmitted to the sound editors. For now, it’s back to the task at hand: finding fat, cutting it, and rearranging the essence.

Murch wrote to Apple manager Brian Meaney in Cupertino, California, to request the beta version of Final Cut Pro 4.0.

March 4, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Revising the battle and pre-battle nips tucks transpositions. Connected up the rabbit in the tunnel with the rabbit in the trench, and all the associated restructuring.

Murch and Minghella settle into what will become their editing routine for the next 12 weeks. This process began with the February 18 showing of the first assembly. The work will revolve in three-week cycles, each interval marked by a screening in Murch’s second floor edit room using Final Cut Pro on the 50-inch plasma monitor for an invited audience of up to ten people, which is all that the room can comfortably contain. After each screening, having debriefed together immediately afterward, editor and director collate their own notes with comments from the others who attended. They review that list, decide priorities, and establish goals for the next screening. Significantly, the entire assembly is not up for grabs each pass; some sections are put aside for a later date while others become the immediate focus. As Murch tries out ideas, makes discoveries, and tightens things up, Minghella is downstairs on his FCP workstation re-examining material, looking at the choice of takes, and otherwise getting himself oriented to the material that Murch reworks upstairs. As Murch gets scenes or sequences sketched out, Minghella goes upstairs to watch, review, discuss, and make decisions. The upstairs-downstairs pattern continues on a daily basis, whenever Minghella is available.

From here on out, editing is, for the most part, all about story, structure, character, and length. There were hints, clues, and portents about these big issues as the dailies flew by over the last six months. But now the material has been “crushed” (first assembly), so the process of revision and reordering can begin in earnest. In film editing, however, unlike the winemaking process, none of the raw material is ever really discarded.

March 4, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Feeling good today though a little tired. Good Chi—thank you!

On a subconscious level, the mass of film, all 111 hours of it, is rooted in Walter Murch’s memory/dream bank, not as an objective database, but as a living organism. A film editor draws on this subliminal source for creative thought and discovery much as a musician does. It is said that musical performers “work” on a piece even when they are away from their instruments, not actually practicing in the corporeal sense. The mind somehow keeps on playing the music surreptitiously, of its own volition, preparing for the next performance while the musician goes about other business, or is asleep. This Jungian stew, these Cold Mountain sounds and images, cooks night and day whether Murch is aware of it or not. Elements reshape and rearrange themselves of their own volition, boiling up into consciousness, sometimes uninvited but always welcomed.

March 5, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Screen for Gabriel, Dennis, Eddie, Alan (Music, VFX, SFX). Went well, but a few miscuts because of improper relinking. Sean says will be fixed by tomorrow.

MARCH 19, 2003—LONDON

Exactly one month after screening the first assembly, Murch and Minghella have cut out 53 minutes, or 17 percent. But removing unnecessary shots isn’t even half the battle. The tricky part is connecting what remains, having shots and scenes work together that were not written to coexist. With new juxtapositions come insights and revelations about characters and meaning. Economical ways to move the story forward are discovered. Remove the wrong support beam, however, and the structure tilts dangerously. Alone together now, upstairs in the Old Chapel, Minghella and Murch play their familiar tune, one they practiced to perfection on two previous motion pictures. The lines between director and editor, editor and writer, writer and director become transparent. With trust, openness, and a Socratic method of inquiry, the duet begins.

“I write notes to Walter as well as discuss things with him,” Minghella says later, sitting on the couch in his roomy office, which is decorated with framed black-and-white production stills from Cold Mountain. “I find that both of us operate on different levels, and sometimes we like to read ideas, sometimes we like to speak ideas. I’ve fallen in with Walter’s requirements. And part of the way he likes to work is to catalog and list and order.”

March 22, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Cut out six and a half minutes from first hour. We made an important connection between the line “store hours” and the match being struck, leading to the “flag” shot—definitely not store hours. Anthony said that he saw how the beginning would work now...

When Minghella and Murch work together, divisions disappear between director and editor, editor and writer, writer and director.

What is it like for to work with Murch? “In the middle of a conversation, Walter will suddenly walk over to a screen and start looking at the rhythms of prime numbers,” says Minghella. “I mean, literally, he will suddenly be examining the logarithmic relationships of one prime number to another. It’s not accidental that his mind is intrigued by patterns at a point when the film is so obsessed with its pattern. And so he finds it important to have lists, and so what we tend to do is both talk around the film, talk of the film, but also to make lists. And those lists of impressions are very significant. He stores them all, catalogs them all.” If Murch wanted to, he could even bring up the English Patient lists now, says Minghella.

“I never discuss with Walter what I think the best take is,” Minghella continues. “I never discuss with him what I think the shot sequence should be. I realize I would miss out on his own creative reaction if he was simply following my instructions. It’s one of the reasons why I don’t like to dictate to him how to solve a problem.”

“People I work with have proved themselves and they play their instruments in a particular way”—Minghella is speaking of Murch, director of photography John Seale, wardrobe designer Ann Roth, first assistant director Steve Andrews, and others. “They are a handful. They are extremely experienced, extremely successful, arguably each of them is the best in their field. They bring with them an enormous amount of baggage. They’re not eager to prove anything. If you’re not interested in that way of playing, then don’t work with them.”

“Of all of them, Walter’s idiosyncrasies are the most pronounced. I’m about to spend a year with Walter, and I know that year will be as defined by his personality and requirements as it will be by mine—an intense, relentless, feast-or-famine experience. Walter can either be closed and silent and remote, or the exact opposite, overwhelmingly warm and embracing and loquacious. If you’re not prepared for the inexplicable changes in temperature in the room, if you’re not prepared for the sudden excursion into issues of the nature of the rotation of the planets, of the derivation of certain words, if you’re not in the market for his particular intellectual and emotional gymnasium, then find somebody else to work with. He has much more to contribute in terms of the atmosphere of the editing process than I do. I don’t see it as my job to control that. I approach it as he says he approaches the film, which is to surrender to the flow of it.”

“Part of the process of making a film, to me, is a process of enabling. It’s about passing on empowerment. The more you can empower everybody, the more likely you are to get the best result. Certainly with Walter, a disempowered Walter is a waste of a huge, huge mind and a huge talent. So I just try to understand his particular requirements and respect them and nourish them, because he is easily destabilized. He has an enormous amount of pride, an appropriate pride. And it simply doesn’t do to mess with that.”