Chapter 11. Bullets Explosions Music People

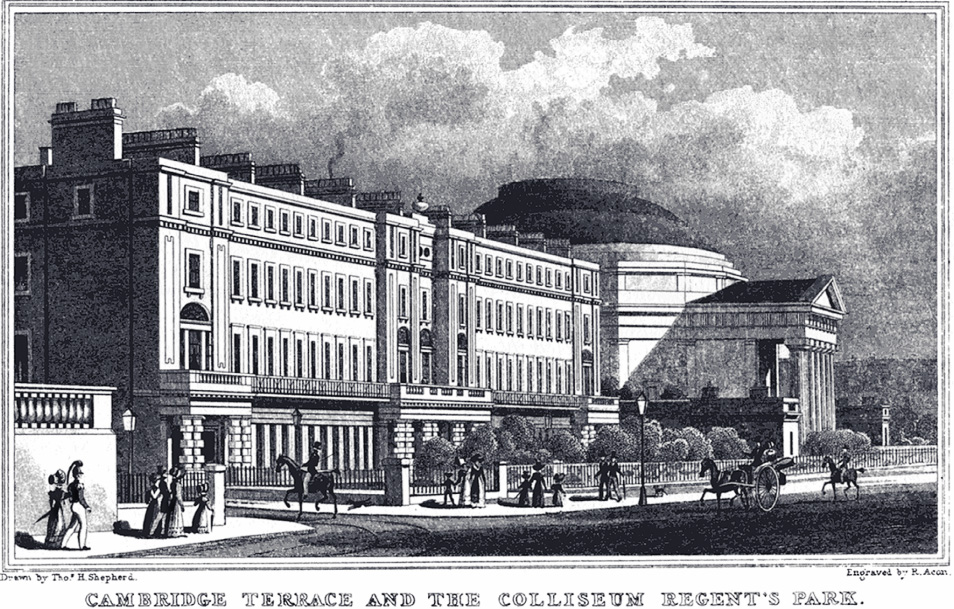

Murch mixes sound at De Lane Lea wearing his lucky sweater. “Aggie’s mother knitted it for her in 1964. A few years later I stole it. It’s got a few scars on it.”

Monday, October 18, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Amazing to remember in retrospect that Francis was not in the room during the mix of Conversation or Apocalypse. I played the mixes for him and he had comments, which we incorporated. Not around during the premixes of Godfather, but he was for the final.

The relationship between a film director and the sound mixer is just as intimate and complex as the one between director and film editor. After all, the mixer realizes the director’s imagination of how a movie will sound. At its simplest, sound mixing means plaiting three disparate elements—music, dialogue, and sound effects—into one harmonious whole. But to achieve that requires tens of thousands, maybe millions of decisions; no one keeps track, least of all mixers, who might blanch if they ever knew. For every sound there are choices about volume, equalization (EQ, or bass/treble), reverberation, synchronization to picture, placement within the speaker array (left, center, right, left-surround, right-surround, boom), the tonal quality of music, transitions between scenes, and more. These are subjective determinations, most of which can only be decided on a trial-and-error basis. There are no predetermined rules or formulas defining what sounds good for a particular film at a particular moment. The mixer brings together elements prepared by the sound editors and, like an orchestra leader who relies on top-notch players, succeeds only by virtue of having the best, properly prepared sound elements to work with.

Unlike filming, where the director approves the composition and angle of every shot before it’s taken, much of post-production sound work happens outside the director’s purview. The director may not be involved in choosing sound effects or even premixing the dialogue. Depending on the director’s personality and interests, he or she will normally participate in more essential aspects of sound preparation, such as recording ADR (automated dialogue replacement) and music taping, but even that isn’t a given.

Murch made eight passes in the sound mix before being satisfied with Inman’s cough.

For the most part, a film director is involved at arm’s length in sound mixing: watching and listening until the mixer is satisfied with the work, and then giving an okay or not. It’s a tedious business, and some directors don’t or can’t participate at such a minute level for the six to eight weeks it normally takes to do a mix from start to finish. In the scene where Inman gets shot, for example, Murch makes eight passes before he is satisfied with the equalization of Inman’s cough—the proper bass/treble, the right density of sound, reverberation, and pitch. He makes 16 refinements until he is happy with the separation he creates between the sound of Ada’s piano and the raindrops splattering on her window during the scene in which she sees her father die.

The mixer has to pay close attention to details, be a savvy audio engineer, operate a complex set of constantly evolving, cutting-edge controls, and work in a give-and-take style with numerous personalities—studio heads, producers, director, editor, other mixers, sound editors, and technical support. Using a professional film mixing theater can run $500 an hour or more, and that’s often without counting the cost of the mixers’ labor. Time and financial pressures make the sound mix a pressure cooker. A professional film sound mixer works under high stress all the time, so it’s no wonder many of them have a reputation for being prickly and forbidding.

The final sound mix occurs at the end of post production, sometimes only a few weeks before the film is released in theaters. By this time, the director isn’t always available to sit in at the mix. Anthony Minghella will be gone from the Cold Mountain mix for days at a time to attend to matters such as last-minute dialogue recording with actors in New York, or major press events, such as an interview with Jude Law and Nicole Kidman on the Barbara Walters show.

Even when he is in London, Minghella must go off to meet with producers, write new dialogue for ADR, check film prints from the lab, and so forth. The soundtrack will not be final, however, until he approves it.

Wearing both hats, as picture editor and sound mixer, enables Murch to keep his and Minghella’s confederated vision for the film intact. In the more typical filmmaking structure, where editing and mixing are handled by two different people, the editor’s extra pair of eyes and ears adds another layer of complexity to an already complicated creative process. The film editor is often marginalized during the sound mix in order to maintain a workable chain of command. One sound facility manager describes “a wall” between mixer and film editor during the typical feature film sound mix.

Sunday, October 19, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Heading to work at 7.20 pm. Already dark. Prep things for the temp mix on Tuesday.

Before starting the final mix on Cold Mountain, Murch must first complete one last temporary mix of the soundtrack so the film can be previewed at advance press screenings. Reviewers for monthly magazines and other publications with long lead times need to see the film right away to make their deadlines. It’s like another dress rehearsal for Murch and the sound team—working with newly revised scenes, new ADR, and finessing their audio work one more time before the real thing. Each new mix version begins where the last one left off. The continuous temp-mixing that began back in June only improves the end result. The movie soundtrack, like sedimentary geological formations, accretes enhancements as it evolves over time.

Because he has to squeeze in a temp mix before the final mix can start, Murch turns to Final Cut Pro for a technological innovation. The sound editors are busy prepping material for the final mix, which begins on Thursday, October 23. Murch decides to do most of the preparation for the temp mix himself at the Old Chapel, in FCP. “The tracks from the previous temp mix had been imported into FCP,” Murch recalls. “I recut them to match the new version, and we used my recut FCP tracks to do the last temp mix at De Lane Lea.” Murch says it saved time, allowed the sound editors to do their work without being bothered, and the result sounded great. The only compromise was using 16-bit digital sound (CD quality), the highest quality Final Cut Pro 3.0 could handle, rather than 24-bit. “I can’t really tell the difference,” Murch admits. “It’s miraculous really that we are able to do this—run FCP tracks straight into the board and get a Dolby 4-2-4, encoded/matrixed mix out of it.” He had pushed Final Cut Pro past another milestone, one neither Murch, DigitalFilm Tree, nor the Apple project team could ever have anticipated.

Thursday, October 23, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Today is first day of final mix. Good luck to all of us. May it go well. God willing.

Just as every scene in a movie must have a purpose if it belongs in the narrative, so the soundscape for a scene must be designed with specific intent. For example, Murch recalls wanting to use the sound of a field of crickets in one of the beginning scenes in Apocalypse Now when Willard is alone in his hotel room at night. “For story reasons,” Murch says, “we wanted the crickets to have a hallucinatory degree of precision and focus.” That led him to bring live crickets into Zoetrope’s basement studio to record them individually, over and over, creating a sound-effects layer with thousands of overlapping chirps. Effective sound design rests on concrete ideas like that. And mixing together such effects, along with music and dialogue, requires the mixer to have the equivalent of a script—a blueprint of sound that instructs his choices.

Walter Murch mixing sound on Apocalypse Now (1979).

Walter Murch has a map to comprehend the universe of sound, and he uses terms of light for its legend. White noise consists of every possible element of sound, just as the color white contains every color of light. Put white noise through an “audio prism” for decoding, and Murch finds the full spectrum for the language of sound. Speech, which he calls “encoded” sound, is at one end of the rainbow—violet. Language is considered to be encoded in the sense that the listener must decode it using linguistic tools to associate meaning. At the other extreme, where red exists in the light spectrum, Murch places music. He calls it “embodied sound,” in the sense that it requires no code for understanding; it can be experienced directly without analysis. In between speech and music are sound effects—half language, half music. They refer to something specific, like crickets chirping or a battle explosion, that requires some thought. Neither completely uncoded like music nor coded like speech, they are yellow, midway in the rainbow of sound colors.

If sound is like color, how might audio composition compare to painting? Murch wrote about this in a 1998 article, “Dense Clarity—Clear Density”: “A well-balanced painting will have an interesting and proportioned spread of colors from complementary parts of the spectrum, so the soundtrack of a film will appear balanced and interesting if it is made up of a well-proportioned spread of elements from our spectrum of ‘sound-colors.’”

Like a memorable painting, be it abstract or realistic, a good soundtrack doesn’t overreach. Trying to do too much with too many colors can produce an undesirable level of complexity that pleases no one. This is what Murch calls the “logjam.” Avoiding excess means, among other strategies, “choosing for every moment which sounds should predominate when they can’t all be included; deciding which sounds should play second fiddle,” he writes. The axiom to help make these choices is Murch’s “Law of Two-and-a-Half.”

The mind seems capable of keeping track of one person’s footsteps in a movie, for example, or even two, but not three or more. Murch had this realization early on, in 1969 when working on George Lucas’s low-budget sci-fi film, THX-1138. In the middle of the night at the Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, Murch recorded sound effects for the movie’s policemen/robots—recording himself clomping through the halls in special metal shoes he built. Later in the edit room, on syncing up the sounds to the images he realized that with two robots, their footsteps had to be in sync with the picture to be believable; but with three robots, none of the footsteps had to sync up exactly. “Our minds give up,” Murch writes. “There are too many steps happening too quickly—the group of footsteps is evaluated as a single entity.”

A soundtrack shouldn’t contain more than two major elements and a minor third—not unlike a musical chord. Or, to put it another way, the soundtrack should simultaneously give the audience a view of both the forest and the trees: “Clarity, which comes through a feeling for the individual elements (the notes), and Density, which comes through a feeling for the whole (the chord). I found this balance point to occur most often when there were not quite three layers of something—my ‘Law of Two-and-a-Half.’”

The physical properties of sound make such layering possible, what Murch calls “harmonic superimposure.” Like musical tones, sounds can be added together while each element retains its identity. The notes C, E, and G create something new, a C-major chord, but you can also hear each of the original notes. If movie sound effects have a relationship with each other (the crickets of Apocalypse Now) they can be multiplied and work in harmony. Pile up too many unrelated sounds on each other (dialogue, music score, auto traffic, a car radio, horns honking, ambulance siren, jet planes, etc.), and there is too much information—white noise. The sound mixer begins with many more sound elements than he can possibly feature at any one time. Like the cinematographer who shows different options of camera angles to a film director, the sound mixer gets a plethora of elements from the sound department, each of which he arranges by priority, or eliminates, depending on his sense of the scene and its relationship to scenes before and after.

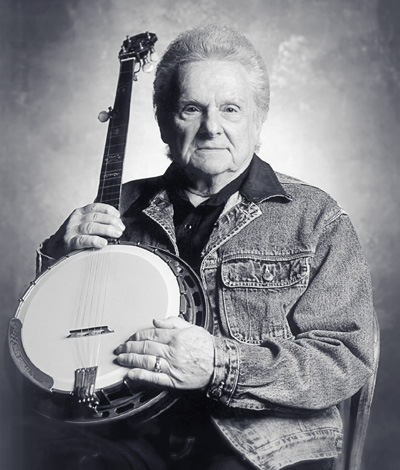

Walter Murch still walks to work, but now it’s two miles in the other direction from Hampstead: south to Soho and De Lane Lea. He joins dozens of other pedestrian commuters through Regent’s Park to London’s central business district. Entering the park from Primrose Hill, it’s a quiet, pleasant route along the Broad Walk adjacent to the London Zoo. These mornings Walter is serenaded by whistles, wails, warbles, and screeches from the nearby monkeys and exotic birds. The animals drive his dog Hana wild as she goes off leash chasing down scents and squirrels. He passes Daguerre’s 1828 Diorama building, which Walter calls “a sort of early 19th Century IMAX experience.” On leaving Regent’s Park at Marylebone Road, he is swept into the clamor of a 21st Century London rush hour: buses, motor scooters, taxis, honking horns, sirens, hundreds of commuters’ conversations—urban white noise, but still “a sort of morning calisthenics for the ears,” he says, “and better than listening to the car radio.”

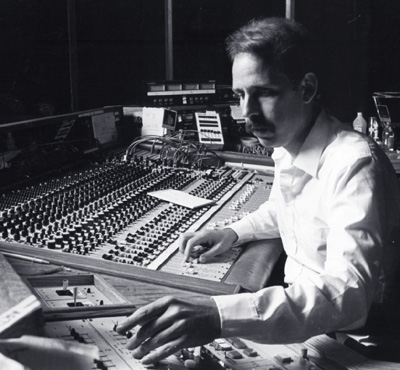

Sean Cullen, Hana, Walter, and Dei Reynolds meet in Walter’s edit room.

Studio A at De Lane Lea is taking on a decidedly lived-in look. The Cold Mountain sound team has been premixing or temp-mixing the soundtrack here on and off for over four months. For two days now a pink bakery box with several chocolate croissants has been on the long table behind the mix console. Bottles of water and days-old newspapers lie around, along with empty coffee mugs, a bowl of fruit, many laptops (all PowerBooks), magazines, piled-up dishes, and assistant Tim Bricknell’s mobile office: a banker’s box full of files. Half a dozen green and blue Ethernet cables snake around the floor for high-speed Internet hookups. If not for the movie screen or the movie sounds, this could be the aftermath of a hacker group’s all-nighter.

A day at the final mix begins unceremoniously. The sound editors and co-mixers are at work when Walter walks in; it’s like coming into a party already in progress—a very loud party. Martin Cantwell, the effects editor, sits at his ProTools station on the right-hand side of the console working on a section from the Battle of Petersburg. The crew greets Walter with cheerful good mornings between short bursts of high-decibel Civil War combat.

Before Murch takes his place at the console, he catches up on who’s doing what, and where. With the finishing work moving so fast, it’s critical for him to know all these details so he can plan for the tasks that lie ahead. Sound supervisor Eddy Joseph tells him that Mark Levinson just dropped off new ADR from the previous night’s loop group recording session with off-camera actors’ voices for the battle scene. As Joseph explains this new dialogue, sound editor Colin Ritchie puts it into the soundtrack on his ProTools work-station. Gruff male voices fill the theater: “Come on! Let’s get ’em, boys!” “Them Yankees gonna die in their own holes.” “We’ve got ’em now, boys!” “Shoot ’em!”

“Mark would have loved to have explained this to us himself,” Joseph tells Murch, “and when he and Anthony are free from Harvey, of course, he will.” He is referring of course to Harvey Weinstein, who has returned to London to check on the film’s progress.

“What’s the Harvey situation?” Murch inquires.

“He’s arriving any minute now.”

“To do what?” Murch asks in between bits of ADR.

“To destroy my edit room, I think,” Joseph says facetiously.

“They’re going to play Harvey the narration, the voiceover?”

“Yeah,” Joseph says. “The voiceover on reel one and reel nine, but also the new letter on reel two.”

“Them Yankees gonna die in their own holes!”

“I opened the door to my edit room this morning and there was Anthony,” Joseph says. “He looked like a zombie.”

“Really? Oh, God,” Murch says.

“Damn Yankees, trapped in...”

“Hurry up! They’re stuck! Shoot ’em!”

“It’s not just tiredness,” Joseph says. “It’s that weight, isn’t it?”

Murch agrees.

“You could feel his shoulders are a little bit down,” Joseph says.

“Tim said he’s just getting angrier and angrier, which is not a good place to be in,” Murch says.

“Not at this stage.”

“Let’s get ’em, boys!”

Like the process of editing the picture, finishing the sound mix consists of making a version, reviewing it, taking notes, addressing those notes in a new version, reviewing that, and so on—for as long as the schedule allows. That’s the theory, anyway. In reality, on a Minghella movie, new sound elements fly in as the mix progresses (ADR from the principal actors, loop group dialogue, revised music, new closing songs, and remixes of already recorded musical score). On the picture side, opening credits, closing credits, the main title sequence, and subtitles are still in process. These new and changing visual elements may throw the soundtrack off kilter, since they could require adjustments to the soundtrack structure, such as allowing more space for Kidman’s voiceover reading supplements to Ada’s letters, or adjusting musical transitions. Murch and the sound crew mix at a moving target.

Unlike picture editing, where it’s just Murch and Minghella (and the occasional producer), the mix is more of a team effort. With so many changes to the soundtrack still being made during the final sound mix, the sound editors from each subdepartment (dialogue, ADR, effects, Foley, music) are all there, standing by to edit the soundtrack right in the theater should that be necessary. The division between sound editing and mixing is becoming less defined. In part it’s because digital sound editing technology makes instant editing possible; and automated mix boards can save settings and versions just like an audio workstation. Given that Minghella encourages collaboration (which Murch enjoys, too), sound editors are not just present, they are consulted during the mix, asked to provide notes on the mix in progress.

“Them Yankees gonna die in their own holes!”

Each reel is just under 20 minutes long and is mixed individually whenever it becomes ready, often out of sequential order. If final audio elements are missing from a reel, or the exact running time of final visual elements is still uncertain, that reel is put off to be mixed later.

So how does Murch start? “I just kind of dive in,” he says. “I’ll listen to tracks in isolation and find out what works particularly well. For example, I may decide in a certain section of the battle to concentrate on people firing at each other and maybe their voices. And we won’t hear much music or other effects, like footsteps.”

Everyone makes a list of what still needs to be fixed as a reel plays through, pegged by timecode. An LCD counter below the screen enumerates elapsed minutes and seconds. Whoever has the first note starts the discussion. It’s an audio symposium among equals; everyone’s items hold equal weight and get debated only if there is disagreement, which is rare.

At this point, about halfway through discussion of reel one, Murch has a note. It concerns the section between the big explosion underneath the Confederate entrenchments and the charge of the Union Army.

“Okay, at 10:07... the horse snorts and it whinnies when it gets up. But then there’s a huff-huff after that, which we could boost. Let’s keep the monitor on dim here [an across-the-board level reduction to permit conversation while mixing]. At 10:42...”

Eddy Joseph jumps in. “Immediately after that, at 10:11, the first bit of the fife. I don’t think you should have that.”

Mike Prestwood-Smith agrees: “I don’t like that, either.”

“It sort of brings us out of the music,” Joseph adds.

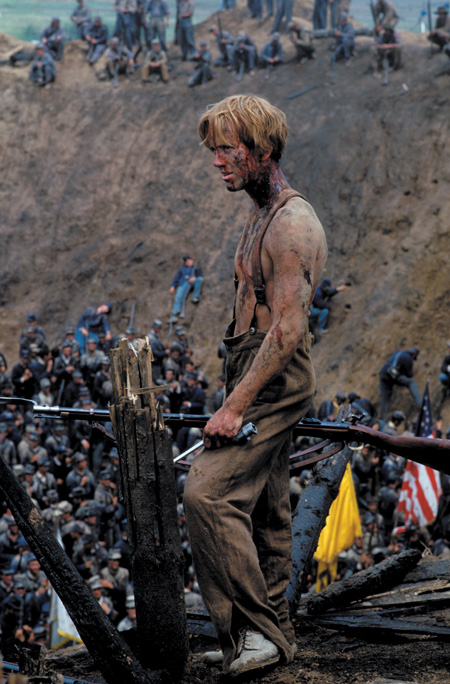

Murch agrees and goes on to the area where the Union Army makes its mad dash from screen left to screen right, Stars and Stripes flying, horses thundering, bayonets rattling, battle cries screeching.

Tuesday November 4, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Finished 3 and starting 1. We ran it through and the battle sounded like a big ball of noise. Guidance and perseverance.

“In general, this is a festival of midrange sounds [600 to 2,000 cycles],” Murch says to the sound crew. “The music is right in that range; the screaming people are in there; so are the small arms, and the rifles—right in there. What is very welcome when I hear them are sounds above and below those frequencies. Like all of the cannon fire and the subharmonic stuff. So we should find out where we have an opportunity to add something down there because it anchors everything. When Oakley hits the other guy, there’s a nice high metallic tinging sound. And also some ricochets and some things up around 5,000 or 6,000 cycles that will sing through. So if you know of any other effects that are like that, we can put them in.”

Matt Gough hits the Play button. The projected picture (downloaded from Final Cut Pro and shown via the video track of Pro Tools for this review) jumps ahead into the peak of battle down in the pit. A chorus sings, a horse whinnies, Oakley yells as he’s run through with a bayonet, explosions go off, men scream.

“We’ve gotten too hot on the clattery guns and stuff,” Matt says.

“The firing of the guns is good,” Murch says. “But it’s the combination of the clatter, the screams, and the rebel yells. It’s too much all on top of itself.”

Later that night at 8:30 pm, walking home from De Lane Lea through the now quiet, darkened streets of central London, Walter reflects on reel one and the issue of loudness and soundtrack complexity.

“Bullets, people, explosions, music—if you’re not careful everything congeals into noise that isn’t particularly interesting. If you play a track loud and then some other track comes along that’s louder than it, you immediately transfer your attention to the louder thing. Then a masking phenomenon takes place. A whole sound element isn’t perceivable. So we have to get rid of it.”

Murch describes the mixer’s task as “directing the attention of the audience’s ears, just as a director of photography directs its eyes.” He wants to give the audience the impression that there is sound for everything, all the time. In fact, only two or three sound concepts are present at any one moment—Murch’s rule of two and a half. Does it get tiring for Murch to mix a sequence like the Petersburg battle? “Because of the noise level it’s exhausting work since we’re immersed in it ten or twelve hours a day. The audience experiences a five-minute scene, but we’re hearing it continuously for two or three days.”

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 2003—SOHO, LONDON

At a lunch break in Studio A, Tim Bricknell, Minghella’s assistant and associate producer of Cold Mountain, sits down on the couch next to Murch. Murch previews these newly revised opening titles and closing credits which are in QuickTime movies on Bricknell’s PowerBook. Debbie Ross, the title sequence artist in Los Angeles, has been creating them using computer imagery. She finished these versions just a few hours ago, uploaded the sequences to a Cold Mountain FTP (file transfer protocol) server, from which Bricknell downloaded them. It’s another stunning one-two punch of digital editing technology and the Internet, increasing convenience while saving time and money.

The title sequence uses visual images of sky, water, and mountains, and Walter comments about the pacing and rhythm among the three elements. “We looked at these like dailies,” Murch says later. “But they are ready to be imported into the film using Final Cut because the graphic sequences are in QuickTime, and Final Cut works on QuickTime.” Prior to these technological advances, Ross would have made a videotape copy of her work (or a film print, if you go back farther in time), which would have been shipped from L.A. to London (two days) for screening.

Murch quickly moves his conversation with Bricknell from visual effects to the most formidable unresolved area still facing Anthony and Cold Mountain: the beginning of the film. Every storyteller knows that the start and finish to a narrative are the most vital—and the hardest to get right. The success of a story is determined right up front, when an audience meets characters, locates itself in space and time, and reads stylistic clues for tone and intention. Likewise, the choices for how a story is resolved determine whether moviegoers leave the theater satisfied, feeling two-plus hours of their time was well spent.

“Pretend you are Anthony for a moment,” Murch says to Bricknell, “and tell me what his thinking is on the whole reel one beginning idea.”

There are three issues: Where does Kidman’s voiceover reading of Ada’s letter begin? Where does the initial subtitle explaining the Battle of Petersburg appear and what will it say? Which music will be used for this entire section, from the studio and producer’s logos to the explosion shot?

So far, Murch hasn’t had a chance to go over these questions directly with Minghella, who just returned to London that morning on the red-eye from New York where he, Bricknell, and ADR supervisor Mark Levinson went to record Kidman reading new material for the expanded voiceover letter. The answers Murch needs bear immediately upon choices he must make about how the picture might require recutting and when to mix which reel.

Bricknell has some tentative answers.

The Kidman voiceover should begin immediately after the producers’ logos but before the main “Cold Mountain” title, he says. Murch asks whether there is enough time to fit it all in. Bricknell believes so, based on Levinson having tried Kidman’s narration against the picture on his laptop during the flight back. The subtitle will go at the end of the initial wide shot that reveals the Southern army’s encampment—what is being called “the rabbit shot,” since it starts with a rabbit coming up out of a hole. But, Murch notes to Bricknell, that shot is 12 seconds too short if the subtitle is going to stay on screen long enough to be read. And since that footage was enhanced much earlier with visual effects to strengthen details in the tableau, this means going back for more visual effects, which takes time. As to the music for the opening, Bricknell reports that Minghella is still undecided: “He’s trying ‘Scarlet Tide’ at the very beginning (a song written for the movie by Elvis Costello), he’s trying ‘Pretty Bird,’ he’s trying Ralph Stanley singing ‘Tarry With Me.’ He also likes the score at the very beginning, over the credits.”

“Okay, Murch says, “when we’re done today, I’ll go back up to the Chapel and sketch that out.”

In an email to producer Bill Horberg about the screenplay back in June 2002, before he had left California for Romania, Murch wrote about the way Cold Mountain begins. “The beginning of the film is harder going than the material past page 35. Which is the way the book was for me—harder to get through the first hundred pages than the rest. The Battle of the Crater is the whole enchilada, and gloriously upends traditional dramatic structure. You expect a film to end with a big battle.”

Murch likened this to Apocalypse Now, and how scenes with Kilgore (Robert Duvall) “front-loaded the film in a way it could never recover from. How could you top it? Nor could Private Ryan, for that matter. We have to watch out for this.”

In addition to beginning with a big battle, there is a basic issue for the audience right at the start: Which side are we on? Who do we root for? “The first voice we hear in the film now is the voice of the Northerner,” Murch says, “and then we see masked soldiers with an American flag going to blow up some other army. The natural unthinking response is the guys in blue (Union) are ‘us’ and those other people in grey (Confederates) are the ‘enemy’—in fact it’s just the opposite.” Inman is the hero of the film and the people to be concerned about are the enemies of the people with the American flag. “So there’s a kind of a warp at the beginning of the film,” Murch continues, “when you alter people’s ordinary preconceptions, which is that anyone with an American flag is on the right side and people with another kind of flag are on the wrong side.”

“The beginnings of films are wildly interpreted differently by different people. Everyone is coming into the theater in a different frame of mind, attaching their own meanings to the opening images. Everyone will put it together slightly differently. It’s very much like the beginning of Touch of Evil [which Murch re-edited in 1998]. It begins with a bomb being set, put in the trunk of a car, and then you wait three minutes and 20 seconds, and then it explodes. Here, instead of Charleton Heston and Janet Leigh, it’s Jude Law and a picture of Nicole Kidman. A bomb is underneath them. Are they going to get blown up? They do, in fact.”

The one-hour break from the sound mix is nearly over, but there’s still enough time for Walter to take Hana out for a walk through bustling, midday Soho. “There are advantages to having me mix the film,” Murch says, trying to keep Hana’s retractable leash from tripping lunchtime walkers hurrying through the narrow alleys. “There is the same brain working on the sound as worked on the images. But a significant disadvantage is that that brain can’t be cloned. I’m not available for emergencies: ‘Break glass and use editor.’ If I were simply the editor, I could come and go from the sound mix and be working on editorial things as the film was being mixed.”

Hana gets twisted around a traffic bollard just outside Golden Square Park before Walter lets her off leash. “There’s so much happening right now, and it’s so end-game, that unless you keep your wits about you, it’s easy to make a stupid critical mistake. We’re always braced for having to stop and re-cut a whole scene. Everyone would be amazed, I think, if that didn’t happen. So far, it looks like it’s not happening. It’s just this issue of extending the rabbit shot out by 12 seconds.”

After lunch, Minghella comes to the mix studio to discuss possible answers for the three remaining issues at the beginning of the film: Kidman’s voiceover, the subtitle, and the music. With Murch engaged as sound mixer, and so much uncertainty surrounding the film’s opening sequence, it’s understandable that Minghella wants Murch’s attention as editor.

“When Walter is out of his running-the-mix-board mode, he needs to sit back here with me, and we need to play, in terms of offering up some alternatives,” says Minghella. “My plan at the moment is that the movie will open with the music we’ve got and keep it going right up until the entry of the tunnel and the barrels. Then we lose that music, the big overture. It does something to the first five minutes that somehow generalizes it. We need to see if there is one piece of ethnic music that can go from there to the explosion. The challenge is, can we have score, silence, ethnic music, and Ada’s voice without everything turning into a blob? It needs Walter to be sitting away from having to push the button so he can help me adjudicate.”

There are two categories of music for Cold Mountain: original “score” composed solely for the film by Gabriel Yared and recorded at Abbey Road Studios in London, and “source music” from the Civil War era chosen by music producer T-Bone Burnett and recorded at his direction in Nashville with musicians such as Ralph Stanley, Alison Krauss, Stuart Duncan, Dirk Powell, and the Sacred Harp Singers. Yared and Burnett work independently of each other, but under Minghella’s direction. Yared first provided musical sketches early on during production, as did Burnett. Once Murch had a first assembly and scenes became more defined, the music was elaborated.

Sometimes Murch ignores the music’s original structural and emotional intentions and uses it the way he feels works best for the film. Over the course of editing for many months much of the score and source music gets shifted around, with Murch finding new places to use it, or even suggesting not to use some of it at all. Creative issues, such as whose music gets used where, can quickly get personal inside a film-in-progress. The buck in this case stops with the director. He is the person on the film whose job it is to resolve conflict and massage bruised egos. One moment this may involve two music composers; a few hours later Minghella might have to explain to an actor doing ADR why she is not rereading lines for her favorite scene—because it got cut.

Wednesday, November 5, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Mixing reel one. Lots of Con Edison “Dig we must for a better New York” barriers up around the music at the beginning, the Ada narration, and the extension of the rabbit “Petersburg” shot. “Can I be excused, teacher?” says Anthony. “I feel sick I have to go home”—only half joking. This is where the S hits the F. Hard slog through reel one with only two hours sleep + burning blood.

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 6, 2003—SOHO, LONDON

Everyone convenes at the mix with fresh ears. Minghella, having slept for the first time in 48 hours, explains his intentions clearly: “Whatever we do should end up with the tunnel shot [of Union soldiers laying explosives] wiping away that piece of music—the whole atmosphere of Ada—like a bit of nostalgia. And then what I’m hoping for is we have silence until we get to the caption, which is ‘Petersburg, Virginia,’ date, and so forth. At which point we get some so-called ‘primitive music.’ And what is that piece of music that carries us to the explosion and makes room for Ada’s voiceover with the letter?”

“And has the right mood,” Murch adds.

Minghella likes the idea of a single singing voice to underlie tranquil scenes of Inman and the other Southern soldiers just before the explosion. He suggests “Tarry with Me,” sung by Ralph Stanley, or “Pretty Bird,” performed by Alison Krauss.

“Do you have an instinct, Walter?” Anthony asks.

Murch comes right to the point: “My instinct is that neither of them will work. The pucker factor is very high. I don’t know if that music lets you sit back and go into this world, setting aside how it fights the dialogue, since both songs use very articulated voices. Is that the way to begin a movie like this? I know ‘Pretty Bird,’ and it’s noble, but may be too noble. It says: This film is going to be good for you.”

“Can I just see the Ralph Stanley?” Anthony asks. “Just play a little bit.” Which co-mixer Michael Prestwood-Smith does. Ralph Stanley is the legendary musician who was brought to an even wider audience through the soundtrack of the Coen brothers’ film, Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?

Ralph Stanley

The initial scene of the movie begins: Union soldiers set explosives underneath unwary Confederate soldiers, and Stanley’s unaccompanied voice emanates from some ancient place:

Tarry with me, O my Savior,

Tarry with me through the night;

I am lonely, Lord, without Thee,

Tarry with me through the night.

We see young Oakley push a wheelbarrow full of dead soldiers’ uniforms through the trenches, stopping where Inman and Swimmer crouch, waiting. “Don’t worry, son, them Yankees keep store hours,” someone says to Oakley. Inman chuckles and takes a dead man’s coat. The rabbit from the establishing shot emerges in the trench and a soldier chases it, shouting, “Keep your paws off my rabbit, keep your paws off my rabbit.” Meanwhile the fuse is burning down below the surface, about to ignite barrels of dynamite. Ralph Stanley sings on. It’s obvious by this point in the sequence that action and music are diverging, with two very different messages: bad things are coming as denoted by the darkness of Stanley’s singing, but the moments on screen are peaceful and comradely.

The sequence comes to an end with the first underground explosion. With hardly any discussion, Murch and Minghella agree that the Ralph Stanley vocal isn’t working here.

Minghella then asks to run the scene with no music, which they do.

Again they watch the Confederate encampment, Oakley, the wheelbarrow, Inman and Swimmer, and the rabbit chase. But it all seems to unfold at half-speed, like a pantomime. Not using any music is not going to work either. As Murch says to Minghella, “The architecture of the shots, the way it’s been edited, says music.”

Minghella realizes that none of the period, or source, music is transposable to this section. Murch agrees. “It doesn’t accommodate itself to what we’ve got.”

It is one of those “expect a miracle” moments, but none arrives at Studio A. Characteristic of the way they work, Minghella and Murch stop on a dime to probe what’s going on artistically, trying to comprehend what the film is telling them while a dozen people in the mix theater wait for a cue to what they’re supposed to do next. This isn’t self-indulgence. Only by understanding why something doesn’t work, why a filmmaker’s intentions are not getting realized, does it becomes possible to figure out a good alternative.

Minghella muses that during the battle and hellish combat down in the pit, source music not only works well, it enhances and deepens those scenes. “Why is it, do you think, that the shape-note singing, ‘Born to Die,’ works in the battle?” he asks rhetorically.

“We’ve earned it,” Murch responds. “We have invested in the film and in the explosion, and we’ve gotten to know the people. And there’s this incredible thing we’re looking at we’ve never seen before. It’s the juxtaposition of that imagery with the choral voices and seeing thousands of people—souls roasting in a pit of hell. There’s a resonance between souls crying out in torment and the sound of the music, and what we’re looking at.”

Minghella has to figure out what should be done, and do it right now. It’s that literal, unglamorous part of film directing that has more to do with managing than creating. Adding to Minghella’s frustration is the fact that he needs Murch to be in two, or even three places at once: with Levinson to help make selections from the previous night’s loop group for the chapel-building scene; discussing music options for the pre-explosion sequence with the two music editors, Alan and Fer; and continuing the final mix by skipping over this problem area for the time being.

“You and I aren’t getting the opportunity to share all the stuff that is going on in other rooms,” Anthony says to Walter. Then he makes a decision: “Alan, Fer, and I would be well used just going away and having a conversation and debate about what possible music we can offer into the mix in terms of the opening. I suggest you, Walter, continue with the mix starting from Ada’s conversation with Inman at the chapel.”

Minghella leaves Studio A with the music editors. The mix picks up in reel one from the scene when Inman and Ada first meet and talk as the chapel is being built—Inman’s flashback. Murch will mix this section knowing that additional loop group voices will be added later to build up the background atmosphere of young men alluding to the looming Southern secession.

Oakley (Lucas Black), the young Confederate soldier.

Murch continues with the mix until nearly 8 p.m. He is particularly fatigued, which is unusual, and takes a cab back to Primrose Hill. On the way home he talks about plans for the next day.

“Harvey is coming tomorrow at 9 a.m. I don’t think to the mix, I think to wrangle with Anthony again.” While Minghella has final cut on the film, the dance between him and the studio is complicated: a director might exercise the final cut prerogative if there’s irreconcilable conflict. But the studio can always find ways to retaliate, such as decreasing what it spends to market and promote a film.

Before leaving for London, Weinstein had been phoning from New York, inquiring about what Anthony was doing, trying to figure out if the studio still has time to recommend, cajole, or argue for changes they might want. “We’ll see tomorrow when Harvey shows up,” Walter says.

Grading the Print

Although the primary job facing Murch is the final sound mix, there are other finishing tasks requiring his attention that are equally important and time sensitive. One is preparing the digital intermediate so it is ready to strike the thousands of release prints of the film for Cold Mountain’s Christmas rollout. CFC, the film lab, finished scanning the camera negative into its computer system. Now the focus is on color-timing the material (called “grading” in the U.K.) using CFC’s proprietary software system to give the movie the look Minghella and cinematographer John Seale intend. Color, contrast, and brightness are adjusted within each shot, and balanced shot to shot so every scene appears seamless. The film gets printed from virgin negative that itself was created from a digital file made by scanning the original camera negative. So every digital reel must be carefully examined to make sure there are no artifacts, excessive graininess, or other imperfections. Only the director can sign off and approve each reel.

Director of photography, John Seale.

Minghella was worried in October when the first answer print came out of the lab for review. The colors he saw on film weren’t matching what he’d seen on the lab’s computer screens. John Seale spent three weeks in September with CFC color timer Adam Glasman, making minute color adjustments in a darkened room. It’s almost unheard of for a director of photography to have so much time to do color timing. But once a decision was made to use a digital intermediate, it only made sense to let Seale take full advantage of its latitude to make precise color adjustments. Normally the DP comes to the lab for color correction after the picture is locked and the negative is cut. That leaves only a small window of time, and by then a DP is often halfway around the world shooting another film. Even getting a DP to come in to do color correction the traditional way for a few days isn’t guaranteed. The digital intermediate process for color correction, however, can start several months before locking picture, giving a DP more flexibility to schedule the timing. Even though grading the negative for a digital intermediate can start well before the picture gets locked, subsequent changes to the edit are easily incorporated by integrating a new edit decision list (EDL) with previously determined color settings.

“We plug in the new EDL that Sean sends us,” Glasman says, “look at the data we’ve got, the grading decisions we’ve made, and make a new version. Then we can just flip through it and tweak accordingly.”

Seale says his first experience with color correction on a digital intermediate is paradise. “It’s so exciting. It’s like being able to get inside the frame and change somebody’s face, just isolate their face, change the color, pump it up a little brighter, take it down... There’s a million things that you can do within the frame.”

In the love scene between Ada and Inman at the end of the film, for example, Seale describes the initial images as “awful yellow-green” because of the way they were digitally scanned. In his color timing, he adds more red to give the scene a warm glow and even introduces a little flicker of yellow light: the burning campfire.

Midway through mixing on November 5, the call comes into Studio A that reel six is arriving fresh from the lab, ready for screening. Finding a stopping point, Murch walks upstairs and goes through the second floor café/lounge to De Lane Lea’s small screening theater. Minghella is on his way from down the street where he’s been working with Levinson selecting new ADR takes. While waiting for him to arrive, Walter engages Glasman in a conversation about the relationship between film print color and the sound mix—that nexus where Murch in particular makes his home. “I’ve just been looking at what we’re mixing to: Final Cut Pro output being projected in video. It achieves some of its dramatic effects by alternating bright, dark, bright, dark, and that visual aggressiveness is working well with the sound. If everything in the film print comes out too muted and dark, then the chemistry between visual and sound will get spoiled.”

Adam Glasman, colorist on Cold Mountain.

Minghella arrives with assistant Bricknell. Claire McGrane is here representing CFC, along with post-production supervisor Michael Saxton. Glasman explains that reel six, which the group is about to screen, is printed “cyan-green, two lights plus,” which means the settings the lab used—the printer’s lights—were too blue by an almost-imperceptible quarter of a photographic stop. These sorts of small inaccuracies are commonplace in the rush of preparing answer prints overnight. Chemicals in the “bath” through which the film travels at the lab are never absolute; neither is their temperature. These variables, along with the trial-and-error nature of film printing, often result in imperfect test prints, which is why they are also called “trial prints.”

Minghella finds it disconcerting to be reviewing a reel that the lab already admits is compromised. “Why is it that they can run it through and come out two points cyan?”

“It’s a hit-and-miss system,” Murch says. “The mysteries of the photochemical process.”

A major film director like Minghella has been through this process many times before. But with the stress of completing Cold Mountain and his executive producer breathing down his neck, he is too worn out to mask his feelings.

“I mean, the difficult thing is we’re going to be looking at a print that’s two points cyan. So it’s hard to navigate the grading, because we’re looking at it through a pair of sunglasses.”

He gets no argument. But unless things are delayed a whole day, Minghella will have to watch the reel and make a mental adjustment as he does.

“So anyway, we’ll look at it.”

The lights go down and reel six begins, playing without sound since it’s a test of just the film’s print quality. It starts with the second part of the Christmas party where Ada, Ruby, and Sally Swanger join Stobrod, Pangle, and Georgia in festive singing and dancing. As the shots go by, Anthony and Walter comment on what they see:

“This is all positive dust, isn’t it?” Anthony asks hopefully, wanting reassurance that occasional dark spots don’t represent unalterable blemishes on the underlying negative.

“Yes,” Glasman says.

“I’m worried about Renée’s lipstick,” Anthony says, thinking Zellweger may look too made up.

The reel plays on to the Sara scene, when Sara invites Inman into her bed. The scene ends with a zoom in on Inman’s face that was produced using a digital visual effect Murch requested. It’s designed to match, compositionally and emotionally, the incoming shot—a similar extreme close-up of Ada’s face at the Christmas party. There is concern that the visual effect shows too much grain, a consequence of enlarging a dimly lit, already grainy shot.

“We were a bit concerned about that zoom to the eye because of the grain,” Glasman says.

Minghella agrees, and adds that the close-up on Jude Law may reveal the makeup effects of his beard.

“Don’t you want to reconsider going back to what we had before?” Minghella asks Murch. Murch agrees.

There is concern about reverse-angle shots of Ada and Ruby listening to the music in the Christmas party. They appear dark in relation to the rest of the scene.

When they’re done watching the reel, Minghella seems happy after all: “The night scenes are looking really superb. You’ve really done beautiful work there. This has been one oasis of pleasure.” The group laughs, knowing Minghella spent most of the morning sequestered with Harvey Weinstein going over another list of change notes.

Then Minghella, Bricknell, and Saxton review the schedule for approving reels from the lab over the next few days. Minghella will fly to Los Angeles the following Wednesday for five days of promotion on Cold Mountain. Claire says she’ll have reel eight for him to see Monday, followed by one on Tuesday and reel nine on Wednesday. Minghella says he’d like to check the sound mix that is underway against these film print reels, as opposed to only hearing the mix while watching the Final Cut Pro digital video version. Using actual film will help Minghella and Murch check sync and also give them a truer idea of how the soundtrack will play in a release print.

No one confirms this request; there probably isn’t time. Minghella can sense the walls closing in. He turns to Saxton and says: “What I don’t want to do, Michael, and I’m not going to do, because it doesn’t make any sense, I’m not going to let go of anybody until I’ve let go of the film. I don’t want anybody to be signed off or let go until I’ve signed off on the movie. And I don’t care what that involves.”

Saxton agrees.

“I don’t want people being shut down or told to return their keys and their machines until we—Walter and I—have said this is where we want to be, even if we have to go back in and keep mixing next week. What is the final day that we need to release this mix?” he asks Saxton.

“Well, it depends. The very first screening is November 24. So we need to ship it by the 22nd. We’ve got—what is it?—a day and a half to print master,” Saxton says, referring to the final transfer of the finished sound mix, ready for marriage to the negative.

“We have to do the print master, then check it,” Murch says, “and then have a buffer in case there’s some problem with the optical negative.”

“We’re keeping everybody on until the print master is finished?” Anthony asks.

“I would if you want to,” Saxton says. “Some, not all, of the sound boys were going to finish at the end of the mix, because for the print master normally it’s just...”

“But when is the end of the mix?” Minghella asks.

“Well, that’s... you tell me.”

“I’m being asked to be schizophrenic.”

“I’ll do whatever you want, Anthony. We’ll keep everyone on. Keep all the options open. I’ve got the mix theater, I think, at least another two weeks.”

“We could be flying in more... I won’t bore you with it all. But there’s a mismatch, a disconnect between finishing the movie and the requirements of the studio.”

“We won’t have the film ready if you want to carry on mixing after you come back from the States,” Saxton says, referring to Minghella’s upcoming promotional trip.

“It’s not whether I want to,” Minghella says. “Want doesn’t have anything to do with anything. We’re still juggling. Walter hasn’t heard stuff we’ve done. We’re working on a reel where we’ve got new information. If there’s a problem when we put all this stuff together and we don’t like the effect of it, then they don’t get the movie. I can’t just deliver a movie when I haven’t seen it.”

Thursday, November 6, 2003, Murch’s Journal

Harvey is here talking to Anthony about the usual issues: Inman death shot (saying it looks like a “police blotter”); and Ada voiceover. Tim said that they were talking about Anthony shooting something new for the transition after Inman’s death. What will happen? Read this in four weeks and tell me. I will be in Toronto evaluating the release print master, hopefully. Endgame decisions.