Essay 5

Learning through practice

Mark Lumley, Architype

Architype has developed a consistent approach to design, energy modelling and project management that has produced a series of exemplar schools. Each project within this substantial body of work has built on lessons from its predecessor. The practice has a fundamental belief in the rigorous study of the schools in use, which is helped by a continuing dialogue with contractors, managers, staff and students. This approach, coupled with the exacting demands of the Passivhaus model, is outlined in a critical review of recent work.

Introduction

Architype has been developing its own approach to the making of ‘sustainable and humanistic’ buildings over a period of several decades. Stimulated by an early interest in timber construction and work with community groups on self-build projects using the Segal method, the practice combines a passion for technical knowledge with a real concern for the experience of building users and for the efficiency of buildings in use. The practice’s working methods have been guided by research through knowledge partnerships and research grants, and by revisiting, observing and measuring their buildings after handover.

This essay explains how five schools36 built for Wolverhampton City Council between 2006 and 2013 provided an opportunity to reflect on good practice and develop lessons learned through a post-occupancy evaluation (POE) feedback loop.

Delivering five buildings with the same client gave rise to a unique set of opportunities:

- the ability to maintain the same design and consultancy team for all five schools and build them with the same contractor (with the exception of Willows Primary & SEN School), building enough confidence to push the design parameters

- procurement at a time when the political climate facilitated proper investment in education infrastructure; Wolverhampton City Council maintained a strong vision for improving its school estate in some of the city’s most deprived areas

- securing a number of research grants that allowed the practice to employ qualified research assistants to undertake detailed post-occupancy assessment.

This delivery process was improved using an extended Soft Landings37 programme on three of the schools, which helped make a positive difference to the occupants, and enabled understanding of how the schools performed in real life, not just as propositions.

A strong feedback loop – the importance of post-occupancy monitoring

The principle of a strong feedback loop was embedded after the first funded study was undertaken, by a full-time researcher in a Knowledge Transfer Partnership (KTP) with Oxford Brookes University between 2006 and 2007.

Despite both the first two Wolverhampton schools scoring highly for user satisfaction in a BUS study, a number of problems were identified: CO2 occasionally reaching higher levels than anticipated in some classes, despite a well-designed natural ventilation strategy; issues relating to the operability (particularly BMS protocols) of windows; and some minor failings in the building envelope relating to thermal bridging and airtightness. The poor energy performance of appliances and fittings, particularly in school kitchens, was also noted. Sub-metering systems were not installed properly, which prevented accurate monitoring of energy use, and there was unsatisfactory commissioning of mechanical and electrical systems generally, often driven by a need to occupy a building as soon as possible.

These initial findings provoked strong reactions in the design team. On the whole this generation of buildings was carefully designed, with expert input from a team of environmental specialists. The schools won design awards and, judging from staff comments, were much loved and enjoyed by their users. Having got so many things right, the design team were justifiably sensitive but resolved to learn from ‘positive criticism’.

Subsequently Architype successfully applied for grants from the Technology Strategy Board (now Innovate UK) to carry out further POE studies on two projects. This helped develop in-house skills for carrying out post-occupancy investigations, in particular with the suite of tools promoted by Innovate UK.

Passivhaus and the follow-on schools

During this period of detailed analysis Architype also started to investigate Passivhaus, in part to gain a better understanding of building physics but also to provide discipline to their intuitive concern for orientation, form factors, eliminating cold bridges, and achieving high degrees of airtightness and much higher U-values. It also forced a review of the impact of ‘unregulated energy’, excluded from Building Regulations, and regard for the performance of all the equipment and appliances going into the building, to meet the Passivhaus Primary Energy target.38

Having successfully delivered St Luke’s and the Willows primary schools, Architype took on two further primary schools, Oak Meadow and Bushbury Hill, and proposed Passivhaus as the energy and comfort standard. Passivhaus seemed to address most of the key areas around building performance that had proven challenging over the previous years – in particular providing a strategy to tackle ventilation heat losses through the use of mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR), which is prescribed by Passivhaus.

The predictive and calculation skills specific to the Passivhaus Planning Package (PHPP) required some learning and support from specialists,39 but the knowledge accumulated through the research studies and the improving technical skills gave Architype a head start.

Significant markers

Achieving Passivhaus certification required further technical improvements, including learning to detail with minimal cold bridges and to achieve high levels of airtightness. Areas of high energy consumption were addressed, for instance the poorly performing kitchens revealed by the KTP study. (These were solved in part by the use of more efficient appliances and electric hobs instead of gas.) IT usage and other electrical consumption were reduced, in particular lighting and its controls. The air supply and extraction were better integrated with the building fabric, and orientation and shading for control of solar gain were also critical factors. The client, design and contractor teams worked well, and there was no need for complex incentives with a common focus on the goal of Passivhaus certification.

The delivery of the first two Passivhaus schools was achieved to a fast programme and came in on budget. Despite some teething problems the schools performed well, and both picked up awards – one a regional RIBA award, the other a national Passivhaus award.

Second-generation Passivhaus and continued learning

Wilkinson Primary School (see Case Study 6) was the last to be completed, in November 2013. This second-generation Passivhaus school benefited from the experiences of the previous projects, with some dramatic simplifications to the building envelope, services and controls (compare, for instance, the section drawings in the case studies).

For the second-generation school there was more engagement with the users, who were given the operational support necessary to run a Passivhaus building. Guidance was also given to the client on the appropriate level of skills required to run the building management system (BMS) and for general operation of the building. Many design decisions were intended to simplify operation – for instance reducing the number of high-level automatic actuators in order to reduce maintenance and improve reliability. However, the building’s different seasonal operation required some understanding on the part of users, and some participation for proper running and optimal comfort (this is discussed in Case Study 6). Improvements like this were also applied retrospectively to the earlier Passivhaus schools.

Handover, commissioning and further engagement

In all the schools the team ran workshops in which they brought school representatives, the head teacher and maintenance staff together with members of the design team, usually the mechanical and electrical engineers, a Passivhaus consultant, contractors and controls installers. Convened as part of a defects resolution process, these meetings aimed to get the right people in the room together to get a reliable account of problems, and find a way to move forward with solutions. The impact of these has been positive, though careful management of technical discussions and reporting is needed to enable useful progress. The group sessions were particularly productive, with vigorous discussion and shared solutions emerging from people who might otherwise have been blaming each other in private and trying to evade responsibility.

The early projects all suffered from reduced commissioning and, faced with deadlines imposed by the school calendar, were handed over earlier than the design team would have liked. Following handover, there were protracted periods of trying to get everything operating properly, particularly the now-familiar problems with operational protocols for BMS. The perseverance and diligence required to get things right at handover should be noted by any architect and client trying to agree the scope of RIBA Stage 7 activities.

Conclusions

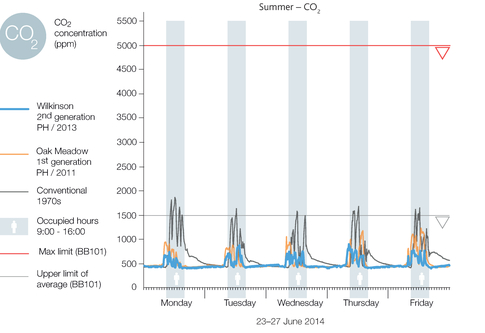

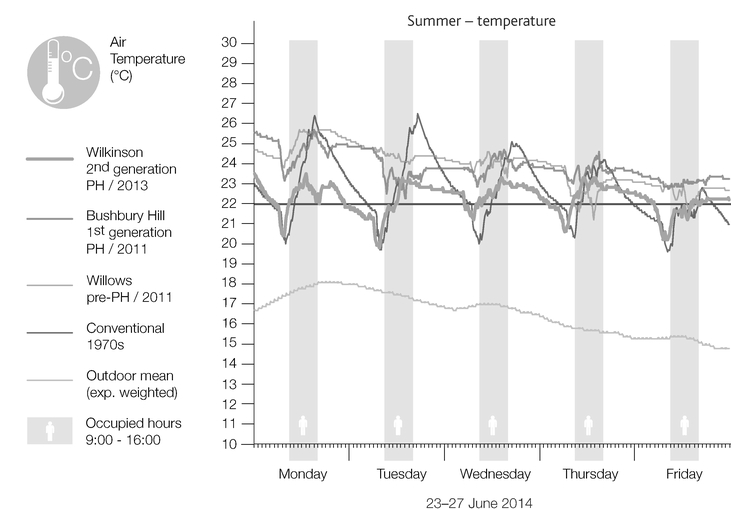

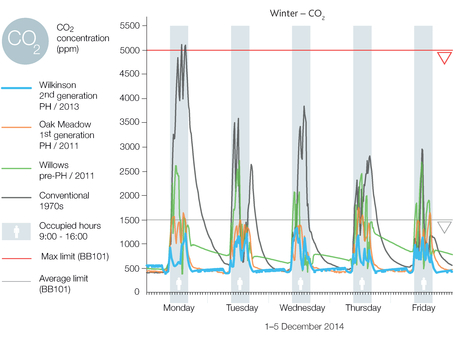

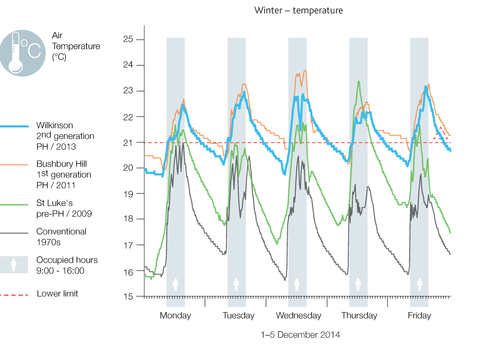

A further KTP study, this time with Coventry University, has been completed, leading to the appointment of a part-time research/POE post within the practice. This study provides a comparison of performance across the five Wolverhampton schools, along with a 1970s school not designed by Architype. Classrooms from each were monitored for CO2 levels, temperature and humidity, and questionnaires were issued to pupils and staff at different points in the year to gain further understanding of the different age perceptions of comfort, and occupants’ ability to affect their immediate environment or comfort level. The findings are powerfully represented by graphs (Figures 02–05), which show clear steps of improvement through the different generations of schools with regards to classroom CO2 levels and temperature stability.

02 Summer CO2

In practice now Architype routinely includes post-occupancy activities to ensure that buildings work as intended – the practice is determined to address the performance gap. A more ambitious target, to be achieved within the next decade, is to be able to provide a guarantee for its buildings’ performance.

Architype’s commitment to stay involved with projects long after their handover is recognised by clients, who have respect for a practice that does not walk away from problems. From a commercial point of view this credibility with clients has had benefits: being offered follow-on work, or receiving the positive references that are essential for winning new work.

Architects who are reluctant to engage with post-completion problems frequently mention concerns over liability, but Architype’s experience has been quite the opposite. When notified, insurers have generally encouraged a proactive approach to dealing with the issues. That is, to get any problems with the building solved in a cooperative manner, to prevent escalation and to avoid conflicts and being drawn into time-consuming disputes.

05 Winter temperature

Ten Elements of a New Professionalism

The theme of cooperation and collaboration runs consistently through Architype’s work, and the practice’s approach is well aligned with many of the principles in the Ten Elements of a New Professionalism promoted by the Usable Buildings Trust40 and the Edge, the campaigning built-environment think tank that commissioned the ‘Collaboration for Change’ report.41

- Be a steward of the community, its resources, and the planet. Take a broad view.

- Do the right thing, beyond your obligation to whoever pays your fee.

- Develop trusting relationships, with open and honest collaboration.

- Bridge between design, project implementation and use. Concentrate on the outcomes.

- Don’t walk away. Provide follow-through and aftercare.

- Evaluate and reflect upon the performance in use of your work. Feed back the findings.

- Learn from your actions and admit your mistakes. Share your understanding openly.

- Bring together practice, industry, education, research and policy making.

- Challenge assumptions and standards. Be honest about what you don’t know.

- Understand contexts and constraints. Create lasting value. Keep options open for the future.42