CHAPTER 5

Learning Objectives

When contrasted with the two levels of objectives previously discussed (Input and Reaction), Level 2 (Learning) objectives need to be more precise and performance driven. This chapter shows typical ways in which learning objectives are developed and used to evaluate skills and knowledge acquisition.

ARE LEARNING OBJECTIVES NECESSARY?

As we move up the chain of impact, the objectives become more important. Few would disagree that learning objectives are more important than having clearly defined input and reaction objectives. While they are all important, learning objectives define what individuals must know to succeed with a project or program. In some programs, such as learning and development, competency building, technology implementation, and leadership development, learning is a critical part of the process—perhaps the most important part. The best learning objectives are those that capture in specific terms what participants must know to be successful.

For compliance programs, where the definition of compliance is based on individuals’ knowledge, a learning objective becomes the most crucial measure. For these programs, learning objectives might be the highest level of objective pursued.

For projects or programs where learning is not as significant, learning and knowledge are still necessary for project implementation success; therefore, learning objectives are required. While all solutions are not learning solutions, all solutions include a learning component. For example, consider an exhibitor at a major conference. The exhibitor uses a booth or display to communicate to current and prospective clients. The ultimate success of the exhibit is usually judged by additional sales or new clients—impact objectives (Level 4). Some would argue that learning is not an issue in this situation and that learning objectives would not be appropriate; however, all levels are in play in this scenario. For example, the exhibitor wants clients to have certain reactions as they approach the exhibit, peruse the information, and discuss products and services with client representatives. The exhibitor wants clients to know about the company, the brand, the message, and the products and services so they can take appropriate steps to make a purchase. Knowledge is critical. Moving on to Level 3, the exhibitor wants clients to follow up with action, such as checking out a product, visiting the website, ordering more informational materials, reviewing a sample, participating in a demonstration, or having a salesperson call. All of these are application objectives, which lead to impact objectives of driving sales. But to be successful in meeting application and impact objectives, the exhibitor realizes that potential clients must first know what the company offers.

HOW TO CONSTRUCT LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Learning objectives require more precision than input and reaction objectives. The best learning objectives are clearly written with action verbs and are performance focused. They might contain conditions and criteria (Mager, 1984).

Action Verbs

Learning objectives usually contain action verbs and are performance based. Specific action verbs reduce the risk of misinterpretation. For example, if a new strategy is being launched and it is expected that participants understand the strategy, an objective might read, “After completion of this session, participants should understand the strategy.” However, this objective is nonspecific and can lead to misinterpretation. The definition of understand is vague. A more precise objective would be, “After completing this session, participants should identify the five elements of the strategy and name the three pillars of the strategy.” These verbs identify action and leave no doubt as to the objective’s meaning. Table 5.1 lists typical specific verbs used in objectives.

Words to avoid are those without clear meaning, such as know, understand, internalize, and appreciate. These words are open to interpretation and should be avoided in learning objectives. This is not to suggest that if a learning objective uses the word understand that it is absolutely wrong. However, it probably is not the best choice to convey meaning, and it opens the door to challenges when time to measure success.

Performance

Essentially, performance describes what the participant will be able to do after participating or becoming involved in a project or program. To be precise, learning objectives must state what the participants will be able to do based on observable (visual or audible) behavior. The key question to ask is what a person will be doing to demonstrate mastery of the particular objective. This leads to the precise action verbs listed in Table 5.1. Consider this example: “Given the detailed client information, write a proposal for the product that meets the client’s needs.” This statement is performance driven, as the participant must produce a proposal, which is a visible action.

The issue of overt and covert objectives is important when addressing performance. An overt objective clearly expresses an action item that can be observed or heard, such as the example above. In a covert objective, the action is internalized, but lacks observable action. For example, in the objective, “Contrast the differences between consumer and commercial loans,” the individual could make the contrast mentally, which would not be visible. This is a covert objective. To make a covert objective more usable, a statement is often added to provide a way to make the objective more observable. For example, the above objective could be rewritten as, “Contrast the differences between consumer and commercial loans, and write the key differences.” The action of writing provides an overt measurement.

| Table 5.1: Action Verbs for Objectives | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conditions

When writing a learning objective, following the performance/action verb approach above is a step toward well-developed learning objectives; however, more detail might be necessary. Sometimes the parameters or conditions under which a person is expected to perform might need to be detailed. For example, consider the objective, “At the end of the conference, write a business development plan.” The question of condition comes into play here. Are participants supposed to write the plan from memory, or will guidelines or templates be provided? We suspect some example or guideline will be offered. So the new objective could be, “At the end of the conference, write a business development plan using the template supplied by the facilitator.” The revised objective gives more detail on the conditions under which the performance should occur.

Conditions can be written in a variety of ways. Table 5.2 shows the typical conditions for learning objectives. They provide additional detail to define what is expected. For example, instead of having an objective to calculate ROI for a technology project, the objective might be reworded as, “Given the total monetary benefits of the project and the total cost of the project, calculate the ROI.” In this statement, detail helps communicate expectations. The amount of detail should be adequate for participants to understand clearly what they must do. It must also be clear to any other stakeholder involved.

Criterion

In addition to action verbs and detailed conditions, a third dimension is helpful in developing learning objectives: stating clearly how well something is to be done. For example, an objective is, “Be able to list eight out of 10 elements of the company’s sexual harassment policy, given a copy of the policy.” The objective is met when eight out of 10 of the policy items are listed, given the policy. The eight out of 10 is the expected level of performance or the criterion for success.

- Given the attached job aid . . .

- Given a list of . . .

- Given any reference of the participant’s choice . . .

- Using a template . . .

- Given a sample size table . . .

- When provided with a standard set of tools . . .

- Given a properly functioning laptop . . .

- Without the aid of references . . .

- Without the aid of a calculator . . .

- With the aid of software . . .

Adapted from Preparing Instructional Objectives (rev. 2nd ed.). Robert F. Mager. california: lake publishing company, 1984.

Criteria can be developed by making use of speed, accuracy, and quality. An example of an accuracy criterion is in the above objective about a company’s sexual harassment policy. This objective focuses on accuracy. We are allowing only two mistakes. Accuracy can be stated in a variety of ways. Table 5.3 presents sample accuracy statements for learning objectives. Each of these provide a criterion that suggests how accurate the demonstration or competency must be.

Speed reflects the desired time required to demonstrate a particular performance. For example, consider the objective, “Be able to classify the type of customer complaint in five minutes, given the complete customer complaint report.” The five-minute timeframe places a speed criterion on the objective.

The third type of criterion is quality. When speed and accuracy are not the critical criteria, a quality measure might be needed. Quality focuses on waste, errors, rework, and acceptable standards. For example, in the objective, “Be able to operate the machine with no more than 2 percent waste,” the percentage of waste allowed is a quality measure. Quality is similar to accuracy, but the two criteria have distinct differences. Consider the objective, “Be able to make 85 percent of the daily sales calls with success ratings of 4.8 or higher from clients.” The 85 percent represents accuracy, while the success ratings reflect the quality of the sales calls.

- . . . with no more than 20% incorrect classifications.

- . . . and solutions must be accurate to the nearest two decimal places.

- with materials weighed accurately to the nearest gram.

- . . . correct to at least three significant figures.

- . . . with no more than two incorrect entries for every 10 pages of the log.

- . . . with the listening accurate enough so that no more than one request for repeated information is made for each customer contact.

Adapted from Preparing Instructional Objectives (rev. 2nd ed.). Robert F. Mager. california: lake publishing company, 1984.

Tips

Learning objectives provide a focus for participants, indicating what they must learn and do—sometimes with precision. Developing learning objectives is straightforward. The key issues are presented in Table 5.4.

CATEGORIES FOR LEARNING OBJECTIVES

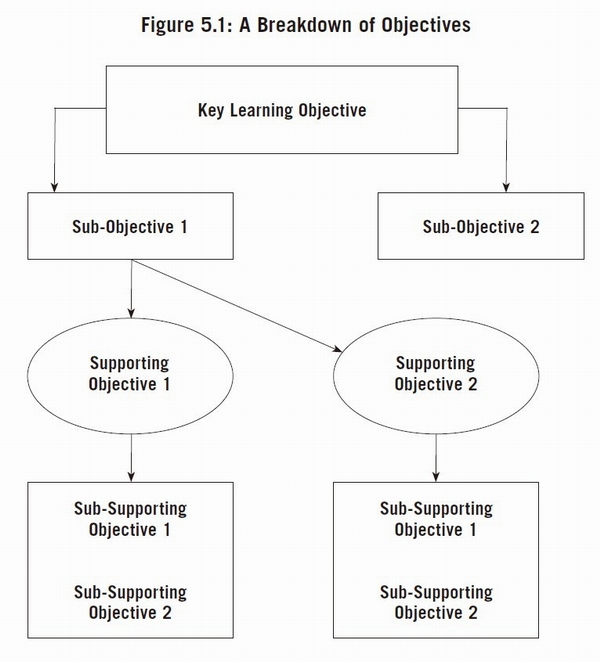

There are several ways to categorize learning objectives. Although they generally focus on skills and knowledge, there are other elements that can be important. Typically, the objectives are broad and only indicate specific major skills or knowledge areas that should be achieved as the program is implemented. These are sometimes called key learning objectives. As shown in Figure 5.1, these objectives break down into subcomponents. Each key objective may have sub-objectives that provide more detail. If necessary, these sub-objectives are broken into supporting objectives and, even further, sub-supporting objectives. This is necessary when many tasks, procedures, and new skills must be learned to make the programs successful. For short programs in which the focus on learning is light, this level of detail might not be needed. Identifying the major objectives and indicating what must be accomplished to meet those objectives are often sufficient.

Learning objectives are critical to measuring learning because they

- Communicate expected outcomes from learning

- Describe competent performance that should be the result of learning

- Provide a basis for evaluating learning

- Focus on learning for participants.

The best learning objectives

- Describe behaviors or actions that are observable and measurable

- Are outcome based, clearly worded, and specific

- Specify what the participant must do as a result of the program

- Have three components:

- Performance—what the participant will be able to do during and after the program

- Condition—circumstances under which the participant will perform the task

- Criterion—degree, amount, or level of accuracy, quality, or time necessary to perform the task.

Three types of learning objectives are

- Awareness—familiarity with terms, concepts, and processes

- Knowledge—general understanding of concepts and processes

- Performance—ability to demonstrate a skill or task, at least at a basic level.

Typical Measurement Categories

Learning measures focus on knowledge, skills, and attitudes, as well as confidence to apply or implement the program or process as desired. Sometimes, learning measures are expanded to different categories. Table 5.5 shows the typical measures collected at this level. Obviously, the more detailed the skills, the greater the number of objectives. Programs can vary, ranging from one or two simple skills to massive programs that may involve hundreds of skills.

Knowledge often includes the assimilation of facts, figures, and concepts. Instead of knowledge, the terms awareness, understanding, or information may be specific categories. Sometimes, perceptions or attitudes may change based on what a participant has learned. For example, in a diversity program, the participants’ attitudes toward having a diverse work group are often changed with the implementation of the program. Sometimes, the desire is to develop a reservoir of knowledge and skills and tap into it when developing capability, capacity, or readiness. When individuals are capable, they are often described as being job ready.

| Table 5.5: Typical Learning Measurement Categories | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When participants use skills for the first time, an appropriate measure might be the confidence that the participants have to use those skills in their job settings. This becomes critical in job situations in which skills must be performed accurately and within a certain standard. Sometimes, networking is part of a program, and developing contacts that may be valuable later is important. This may be within, or external to, an organization. For example, a leadership development program may include participants from different functional parts of the organization, and an expected outcome, from a learning perspective, is to know who to contact at particular times in the future.

Cognitive Levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy

Benjamin Bloom and other psychologists created a system for describing, in detail, different levels of cognitive functioning so that the precision of testing cognitive performance could be improved (Bloom, 1956). The result of this effort was a classification system that breaks cognitive processes into six types: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. The scheme is called a taxonomy, because each level is subsumed by the next, higher level. Since its creation, the taxonomy has been widely used to classify the cognitive level of learning objectives.

- The knowledge level is the lowest level of the taxonomy and simply indicates the ability to remember content in exactly the same form in which it was presented.

- The comprehension level consists of one of the following:

- Participants restate material in their own words.

- Participants translate information from one form to another.

- Participants apply designated rules.

- Participants recognize previously unseen examples of concepts.

- The application level requires participants to decide what rules are pertinent to a given problem and then to apply the rules to solve the problem. Although the term application is used, it is still a learning objective.

- At the analysis level, participants are required to break complex situations into their component parts and figure out how the parts relate to and influence one another.

- The synthesis level requires the creation of totally original material: products, designs, equipment, and so forth.

- The evaluation level is the highest level of Bloom’s taxonomy. This level requires participants to judge the appropriateness or value of some object, plan, design, and so on, for some purpose (Shrock & Coscarelli, 2000).

For most projects or programs, these levels of learning might not be necessary. For significant learning solutions, however, it might be helpful to classify objectives by these categories.

HOW TO USE LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Learning objectives are highly useful, giving projects proper direction and guidance. Here are five important uses.

Program Design

Learning objectives give specific direction to the designers. Using the objectives, designers build the appropriate content into the exercises, skill practice tests, and assessments.

Program Facilitation

Learning objectives give proper direction to facilitators by helping them understand what they must teach. For project leaders, these objectives show what participants and others involved in the project must know to make the project successful. They receive direction and guidance to ensure that the knowledge and skills are acquired by participants.

Marketing

Learning objectives are often important in marketing a project or program. They show what participants will learn to implement the project or program and make it successful. Detailed learning objectives might attract additional participants.

Participant Confidence

Learning objectives are fundamental information for participants. Before, during, and after the project or program, the objectives remind participants of what they should learn to make the program successful. These objectives provide clear direction of what is needed and perhaps the motivation to learn some of the material in advance of the program initiation.

Compliance

Sometimes learning objectives are used for compliance purposes. They show what must occur to meet a mandatory compliance or regulatory requirement. In these cases, objectives align with the requirements. When the objectives are met, the requirements are satisfied.

EXAMPLES

Table 5.6 shows some typical learning objectives. These objectives are critical to measuring learning. They communicate the expected outcomes of learning and define the desired competence or performance necessary for program success.

After completing the program, participants will be able to

- Identify the six features of the new ethics policy

- Demonstrate the use of each software routine in the standard time for the routine

- Use problem-solving skills, given a specific problem statement

- Determine whether they are eligible for the early retirement program

- Score 75 or better in 10 minutes on the new-product quiz

- Demonstrate all five customer-interaction skills with a success rating of 4 out of a possible 5

- Explain the five categories for the value of diversity in a work group

- Document suggestions for award consideration

- Score at least 9 out of 10 on a sexual harassment policy quiz

- Identify five new technology trends explained at the conference

- Name the six pillars of the division’s new strategy

- Successfully complete the leadership simulation in 15 minutes.

Table 5.7 shows the actual objectives taken from an annual agents conference organized by an insurance company. As you can see, it specifically indicates what the agents must learn at the conference (Phillips, Myhill, & McDonough, 2007).

After completing the conference, participants should be able to

- Identify the five steps for business development strategy

- Develop a business development plan, given a template

- Select the best community service group to join for business development

- Explain the changes in products within 10 minutes

- Identify the five most effective ways to turn a contact into a sale

- Identify at least five agents to call for suggestions and advice.

Adapted from “neighborhood insurance company case study,” Proving the Value of Meetings and Events. J.J. Phillips, M. Myhill, & J. Mcdonough. birmingham, alabama: ROI institute and Mpi, 2007.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Learning objectives, representing the second level of success in the chain of impact, are more involved than input and reaction objectives, as they must be clearly stated to prevent misinterpretation. Ideally, they should include an action verb, a performance statement, a condition, and a criterion. Not every objective should have all these elements, but these are the components necessary to make a comprehensive learning objective. For projects and programs where the learning component is prominent, learning objectives become extremely critical and must be developed with precision. When they are defined clearly, they provide direction for groups to build content and understand what is necessary to make the project successful. Chapter 6 will focus on the next level of objectives, application objectives.

EXERCISE: WHAT’S WRONG WITH THESE LEARNING OBJECTIVES?

Table 5.8 presents a list of learning objectives that need improvement. Indicate the concerns about the objectives, as stated. Responses to this exercise are provided in Appendix A.

- Given a one-hour session, be able to understand the difference among rebate, adjustment, and fee waiver.

- The participant will learn basic construction standards in the home-building industry, according to local and state codes.

- Understand the principles of leadership.

- Be able to recognize that the implementation of a great place to work requires time, adjustment, and continuous effort.

- Appreciate the viewpoint of others and perform as a great teammate.

- Demonstrate knowledge of the principles of project management.

- Be able to know well the major rules of spin selling.

- Be able to develop logical approaches to the solution of network downtime.