CHAPTER 8

ROI Objectives

At first glance, one might wonder why we need an entire chapter to talk about ROI objectives. Isn’t it merely a number? The short answer is, yes, it is a number; however, different formulas can be used to reach this number. There are specific issues that need to be addressed to use ROI appropriately.

The decision to have an ROI objective should be taken seriously. The program selected for this level of analysis should be carefully chosen. The basic premise for setting ROI objectives is that data will be collected to determine if the objectives are met. The development of ROI calculations involves important steps that go beyond what is covered in this chapter, although they are briefly mentioned. The following pages present not only the rationale for having an ROI objective, but also the ways in which it can be constructed, interpreted, and used.

ARE ROI OBJECTIVES NECESSARY?

ROI is the ultimate level of evaluation, as it compares the actual cost of a program or project to its monetary benefits. Some program sponsors demand this measure, while other stakeholders are daunted at the thought of fully exposing the program results (or lack of results). A negative ROI is always a concern.

ROI must be used carefully and reserved only for key strategic programs— important, expensive, and high-profile initiatives. To calculate ROI, the impact measures discussed in chapter 7 are converted to money and compared to program costs (using a fully loaded cost—both indirect and direct).

An ROI objective meets an important demand that is intensifying in organizations. As shown in Figure 8.1, the Show Me Evolution has occurred. Executives and key stakeholders have made higher-level demands on projects and programs, ranging from “Show me” to “Show me the real money, and make me believe it is a good investment.” To achieve the latter, the process must be credible, and an ROI calculation must be made. Converting data to money and developing the fully loaded costs are beyond the scope of this book. Many other books show how this is accomplished (Phillips & Phillips, 2007; Phillips & Zuniga, 2008).

| Figure 8.1: The Show Me Evolution | |

| Term | Issue |

| Show Me! | Collect impact data . . . |

| Show Me the Money! | And convert data to Money . . . |

| Show Me the real Money! | And isolate the effects of the project . . . |

| Show Me the real Money, and Make Me believe it is a good investment! | And compare the Money to the cost of the project. |

In short, ROI is a powerful objective that can serve as the answer to accountability concerns for some program sponsors and owners. For others, it conjures anxiety and disappointment.

BASIC ROI ISSUES

ROI objectives are based on formulas. Before presenting these formulas, we explore a few basic issues that must be understood before developing ROI objectives.

Definition

The term return-on-investment is occasionally—and sometimes intention-ally—misused. This misuse broadly defines ROI, including any benefit from the program. For example, it is common to have someone claim, “This program has a great ROI.” In that case, ROI is a vague concept. In this book, return-on-investment is precise and represents an actual value by comparing program costs to benefits. The two most common measures are the benefit-cost ratio (BCR) and the ROI percentage. Both are used, along with other approaches, to calculate the economic return or payback.

For many years, program leaders have sought to calculate the actual return-on-investment in programs and projects. If the program is considered an investment—not an expense—then it is appropriate to place it in the same funding process as other investments, such as the investment in equipment and facilities. Although the other investments might be different, executives and administrators often see them in the same light. Developing specific objectives that reflect the desired return on the investment is critical for the success of these programs.

Annualized Values: A Fundamental Concept

Using annualized values is an accepted practice for developing ROI in many organizations. All the formulas presented in this chapter use annualized values so that the first-year impact of the program can be calculated. This approach is a conservative way to develop ROI, as many short-term programs add value in the second or third year. For long-term programs, longer timeframes are used. For example, in an ROI analysis of a program involving self-directed teams in Litton Industries, a seven-year timeframe was used. For short-term programs that last only a few weeks, first-year values are more appropriate. Consequently, ROI objectives usually represent a year of monetary value measured not at the beginning of the program, but from the point where the impact is established.

HOW TO CONSTRUCT ROI OBJECTIVES

When selecting the approach to measure ROI and develop an objective, it is important to communicate to the target audience the formula used and the assumptions made in arriving at the decision to use this formula. This helps avoid confusion surrounding how the ROI value was actually developed. The two preferred methods, the benefit-cost ratio and the basic ROI formula, are described next.

Benefit-Cost Ratio

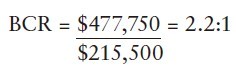

One of the oldest methods for evaluating projects and programs is cost-benefit analysis. This method compares the benefits of the program to the costs, resulting in a simple benefit-to-cost ratio. In formula form, the ratio is

In simple terms, the BCR compares the annual economic benefits of the program to the costs. A BCR of 1 means that the benefits equal the costs. A BCR of 2, usually written as 2:1, indicates that for each dollar spent on the program, two dollars are returned in benefits. The following example illustrates the use of the BCR. A behavior modification program designed for managers and supervisors was implemented at an electric and gas utility. An ROI objective of 50 percent was established. This is the minimum acceptable ROI value, set by the client. This translates to a target BCR of 1.5:1. In a follow-up evaluation, action planning and business performance monitoring captured the benefits. The first-year payoff for the program was $477,750. The fully loaded implementation cost was $215,500. Thus, the ratio was:

For every dollar invested in this program, 2.2 dollars in benefits were realized. The principal advantage of using this approach is that it avoids traditional financial measures, so confusion does not arise when comparing program investments with other investments in the company. Investment returns in plants, equipment, or subsidiaries, for example, are not usually reported using the benefit-cost ratio. Some program leaders prefer not to use the same formula to compare the return on program investments with the return on other investments. In these situations, the ROI for programs stands alone as a unique type of evaluation.

Unfortunately, no standards exist that constitute an acceptable BCR from the client perspective. A standard should be established within the organization, perhaps even for a specific type of program. However, a 1:1 ratio (breakeven) is unacceptable for many programs. In others, a 1.25:1 ratio is required, where the benefits are 1.25 times the cost of the program.

ROI Formula

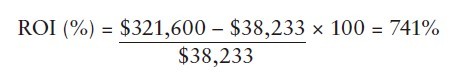

Perhaps the most appropriate formula for evaluating program investments is by comparing net program benefits to program costs. This is the traditional financial ROI and is directly related to the BCR. The comparison is expressed as a percentage when the fractional values are multiplied by 100. In formula form, the ROI is

Net program benefits are program benefits minus costs. The ROI value is related to the BCR by a factor of 1. Subtract 1 from the BCR and multiply by 100 to get the ROI percentage. In the electric and gas utility example, a BCR of 2.2:1 is the same as an ROI value of 120 percent (2.2 – 1 = 1.2, and 1.2 × 100 = 120 percent). This value exceeds the 50 percent ROI objective. This formula is essentially the same as the ROI for capital investments. For example, when a firm builds a new plant, the ROI is developed by dividing annual earnings by the investment. The annual earnings are comparable to net benefits (annual benefits minus the cost). The investment is comparable to fully loaded program costs, which represent the investment in the program.

An ROI of 50 percent means that the costs are recovered, and an additional 50 percent of the costs are reported as “earnings.” A program ROI of 150 percent indicates that the costs have been recovered, and an additional 1.5 times the costs are captured as “earnings.”

The following example illustrates the ROI calculation. Public and private sector groups have been concerned about literacy and have developed a variety of programs to tackle the issue. Magnavox Electronics Systems Company was involved in a literacy program that focused on language and math skills for entry-level electrical and mechanical assemblers. The ROI objective was 25 percent. The results of the program were impressive. Productivity and quality alone yielded an annual value of $321,600. The fully loaded costs for the program were just $38,233. Thus, the return-on-investment was

For each dollar invested, Magnavox received $7.41 in return after the costs of the literacy program had been recovered.

Using the ROI formula essentially places program investments on a level playing field with other investments using the same formula and similar concepts. The ROI calculation is easily understood by key management and financial executives who regularly use ROI with other investments.

ROI Interpretations

“Earnings” can be generated through increased sales or cost savings. In practice, more opportunities for cost savings occur than for profits. Cost savings can be generated when improvements in productivity, quality, efficiency, cycle time, or actual cost reduction occur. Of the nearly 500 studies we have reviewed, the vast majority were based on cost savings. Approximately 85 percent of the cases in the studies had a payoff based on output, quality, efficiency, time, or cost reduction. The others had a payoff based on sales increases, where the earnings were derived from the profit margin. This is important for nonprofits and public sector organizations for which the profit opportunity is often unavailable. Most programs will be connected directly to cost savings, or cost avoidance. ROI can still be developed in those settings, based on costs saved or avoided.

Financial executives have used the ROI approach for centuries. Still, this technique did not become widespread in industry for evaluating operating performance until the early 1920s. Conceptually, ROI has intrinsic appeal because it blends all the major ingredients of profitability into one number; the ROI statistic by itself can be compared with opportunities elsewhere (both inside and outside). Practically, however, ROI is an imperfect measurement that should be used in conjunction with other performance measurements (Horngren, 1982).

It is important that the formula outlined above be used in organizations. Deviations from or misuse of the formula can create confusion among users and finance and accounting staffs. The chief financial officer (CFO) and the finance and accounting staff should become partners in the use of ROI. Without their support, involvement, and commitment, using ROI on a wide-scale basis is difficult. Because of this relationship, the same financial terms must be used as those used and expected by the CFO.

Table 8.1 shows examples of misuse of financial terms in the literature. Terms such as return-on-intelligence (or return-on-information) abbreviated as ROI do nothing but confuse the CFO, who is thinking that ROI is the actual return-on-investment described above. Sometimes, return-onexpectations (ROE), return-on-anticipation (ROA), or return-on-client expectation (ROCE) are used, confusing the CFO, who is thinking returnon-equity, return-on-assets, and return-on-capital employed, respectively. Use of these terms in the calculation of payback of a program will do nothing but confuse others and perhaps cause you to lose the support of the finance and accounting staff. Other terms, such as return-on-people, return-on-resources, return-on-technology, and return-on-objectives, are often used, with almost no consistent financial calculations. The bottom line: Do not confuse the CFO. Consider this individual an ally, and use the same terminology, processes, and concepts when applying financial returns for programs.

| Table 8.1: Misuse of Financial Terms | ||

| Term | Misuse | CFO Definition |

| ROI | Return-on-information, return-onintelligence, or return-on-inspiration | Return-on-investment |

| ROE | Return-on-expectation or return-oneffort | Return-on-equity |

| ROA | Return-on-anticipation | Return-on-assets |

| ROCE | Return-on-client expectation | Return-on-capital employed |

| ROP | Return-on-people | ?? |

| ROR | Return-on-resources | ?? |

| ROT | Return-on-technology or return-ontraining | ?? |

| ROW | Return-on-Web | ?? |

| ROO | Return-on-objectives | ?? |

Specific ROI Targets

Specific objectives for ROI should be developed before an evaluation study is undertaken. While no generally accepted standards exist, four strategies have been used to establish a minimum acceptable requirement, or hurdle rate, for ROI in a program. The first approach is to set the ROI using the same values used to invest in capital expenditures, such as equipment, facilities, and new companies. For North America, Western Europe, and most of the Asia Pacific area (including Australia and New Zealand), the cost of capital is quite low, and the internal hurdle rate for ROI is usually in the 15 to 20 percent range. Using this strategy, organizations would set the expected ROI at the same value expected from other investments.

A second strategy is to use an ROI minimum that represents a higher standard than the value required for other investments. This target value is above the percentage required for other types of investments. The rationale: The ROI process for programs is still relatively new and often involves subjective input, including estimations. Because of that, a higher standard is required or suggested. For most of North America, Western Europe, and the Asia Pacific area, this value is set at 25 percent.

A third strategy is to set the ROI value at a break-even point. A 0 percent ROI represents breakeven. This is equivalent to a BCR of 1. The rationale for this approach is an eagerness to recapture the cost of the program only. This is the ROI objective for many public sector organizations. If the funds expended for programs can be captured, value and benefit have come from the program through the intangible measures—which are not converted to monetary values—and the behavior change that is evident in the application and implementation data. Thus, some organizations will use a break-even point, under the philosophy that they are not attempting to make a profit from a particular program.

Finally, a fourth, and sometimes recommended, strategy is to let the client or program sponsor set the minimum acceptable ROI value. In this scenario, the individual who initiates, approves, sponsors, or supports the program establishes the acceptable ROI. Almost every program has a major sponsor, and that person may be willing to offer the acceptable value. This links the expectations of financial return directly to the expectations of the individual sponsoring the program.

OTHER ROI MEASURES

In addition to the traditional BCR and ROI formulas previously described, several other measures are occasionally used under the general term return-oninvestment. These measures are designed primarily for evaluating capital expenditures, but sometimes work their way into program or project evaluations.

Payback Period

The payback period is another common method for evaluating capital expenditures. With this approach, the annual cash proceeds (savings) produced by an investment are compared to the initial cash outlay required by the investment. Measurement is usually in terms of years and months. For example, if the cost savings generated from a program are constant each year, the payback period is determined by dividing the total original cash investment (development costs, expenses, and so forth) by the amount of the expected annual or actual savings (program benefits). To illustrate this calculation, assume that an initial program cost is $100,000 with a three-year useful life. The annual savings from the program is expected to be $40,000. Thus, the payback period becomes

The program will “pay back” the original investment in 2.5 years. The payback period is simple to use, but has the limitation of ignoring the time value of money. Thus, it has not enjoyed widespread use in evaluating program investments.

Discounted Cash Flow

Discounted cash flow is a method of evaluating investment opportunities in which certain values are assigned to the timing of the proceeds from the investment. The assumption, based on interest rates, is that a dollar earned today is more valuable than a dollar earned a year from now.

There are several ways to use the discounted cash flow concept to evaluate a program investment. The most common approach is the net present value of an investment. This approach compares the savings, year by year, with the outflow of cash required by the investment. The expected savings received each year is discounted by selected interest rates. The outflow of cash is also discounted by the same interest rate if the investment is ongoing, otherwise the initial outlay of cash is used. If the present value of the savings should exceed the present value of the outlays, after discounting at a common interest rate, management usually considers the investment to be acceptable. The discounted cash flow method has the advantage of ranking investments, but it becomes difficult to calculate.

Internal Rate of Return

The internal rate-of-return (IRR) method determines the interest rate required to make the present value of the cash flow equal to zero. It represents the maximum rate of interest that could be paid if all project funds were borrowed and the organization had to break even on the projects. The IRR considers the time value of money and is unaffected by the scale of the project. It can be used to rank alternatives or to make accept/reject decisions when a minimum rate of return is specified. A major weakness of the IRR method, however, is that it assumes all returns are reinvested at the same internal rate of return. This can make an investment alternative with a high rate of return look even better than it really is, and a project with a low rate of return look even worse. In practice, the IRR is rarely used to evaluate program investments.

CAUTIONS WHEN USING ROI

Because of the sensitivity around the use of ROI, caution is needed when developing, calculating, and communicating the return-on-investment. The use of ROI objectives and the implementation of the ROI process is a very important issue and a goal of many functions. The following cautions are offered when using ROI.

Take a Conservative Approach

Conservatism in ROI analysis builds accuracy and credibility. What matters most is how the target audience perceives the value of the data. A conservative approach is always recommended for both the numerator of the ROI formula (net program benefits) and the denominator (program costs.)

Use Caution

There are many ways to calculate the return on funds invested or assets employed. The ROI is just one of them. Although the calculation for ROI in your project uses the same basic formula as in capital investment evaluations, it might not be fully understood by the target group. Its calculation method and its meaning should be clearly communicated. More important, it should be an item accepted by management as an appropriate measure for program evaluation.

Involve Management

Management ultimately makes the decision as to whether an ROI value is acceptable. To the extent possible, management should be involved in setting the parameters for calculations and establishing targets by which programs are considered acceptable within the organization.

Fully Disclose the Assumptions and Methodology

When discussing the ROI Methodology and communicating data, it is important to fully disclose the process, steps, and assumptions used in the process.

Teach Others

Each time an ROI is calculated, the project leader should use this opportunity to educate other managers and colleagues in the organization. Even if it is not in their area of responsibility, these individuals will be able to see the value of this approach to evaluation. Also, when possible, each project should serve as a case study to educate the team on specific techniques and methods.

Not Everyone Will Buy Into ROI

Not every audience member will understand, appreciate, or accept the ROI calculation. For a variety of reasons, one or more individuals might not agree with the values. These individuals might be highly emotional about the concept of showing accountability for projects. Attempts to persuade them might be beyond the scope of the task at hand.

Do Not Boast About a High Return

It is not unusual to generate what appears to be a very high return-on-investment for a program. A project manager who boasts a high return will be open to potential criticism from others unless there are indisputable facts on which the calculation is grounded.

Choose the Time and Place for Debate

The time to debate the ROI Methodology is not during the project evaluation (unless it cannot be avoided). There are constructive venues for debate on the ROI process, such as in a special forum, among the project team, in an educational session, in professional literature, on panel discussions, or even during development of an ROI impact study. Debating at an inappropriate time or place can detract from the quality and quantity of information presented.

HOW TO USE ROI OBJECTIVES

Program Design

An ROI objective provides extreme focus. Not only must business impact measures improve, but they must improve enough to overcome the cost of the program. This sets a clear expectation—one that can create high levels of motivation or anxiety, depending on how individuals perceive the objectives. In planning, organizers create appreciation for the proper use of ROI. It might require education so participants understand their roles.

Program Facilitation

For facilitators, obviously, the pressure is on when an ROI is included. The focus is intense, and those involved must do what they can to make it work for them. For programs with potentially high impact, the ROI can be extremely motivational, as it places a significant challenge before the participants and facilitator.

Management and Executives

Perhaps the group that relates to ROI objectives most is the management team. Managers and executives involved in projects clearly see the project’s value. Now they see that there is an ROI objective. Senior executives who approve the funding are much more satisfied with a project when there is an ROI objective. This enables them to rest comfortably, knowing that if the objective is met, the investment generates a positive return.

Marketing

There is no more powerful measure than a positive ROI to show the value of a project. When developed and calculated credibly, it can be used to convince others to become involved or persuade other sponsors to pursue similar projects. When the ROI is negative, stakeholders gain information as to what they could do to make it positive and successful. This is powerful data for all current and prospective stakeholders.

ROI Is Not for Every Program

ROI objectives should not be applied to every project or program. ROI objectives are appropriate for programs that meet criteria such as these:

- Important to the organization to meet operating goals. These programs are designed to add value. ROI may be helpful to show that value.

- Closely linked to strategic initiatives. Anything this important needs a high level of accountability.

- Very expensive to implement. An expensive program, requiring large amounts of resources, should be subjected to this level of accountability.

- Highly visible and sometimes controversial . These programs often require this level of accountability to satisfy the critics and the concerned.

- Targeted at a large audience. If a program is designed for all employees, it may be a candidate for ROI because of the exposure, resources, and time.

- Of interest to top executives and administrators. If top executives are interested in the ultimate impact of programs and projects, then the ROI should be developed.

These are only guidelines and should be considered within the context of the situation and the organization. Other criteria may also be appropriate. These criteria can be used in a process to sort out those programs most appropriate for this level of accountability.

It is also helpful to consider the programs for which ROI objectives are not appropriate. ROI is seldom appropriate for programs that are very short in duration, are very inexpensive, are legislated or required by regulation, are required by senior management, or serve as a basis to teach required skills for specific jobs. This is not meant to imply that an ROI objective (and subsequent ROI Methodology) cannot be implemented for these types of programs. However, when considering the limited resources for measurement and evaluation, careful use of these resources and time will result in evaluating more strategic types of programs.

FINAL THOUGHTS

This chapter explores the challenging yet rewarding issue of ROI objectives. Not every program should have an ROI objective. In fact, most programs should not. Expensive, high-profile, strategic programs are the most appropriate for an ROI objective. This chapter describes how the ROI objectives are developed using a variety of calculations, with the most common calculation being ROI expressed as a percentage. Use of an ROI objective should be pursued carefully and deliberately.