6

The Fable of Price Swings as Bubbles

THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS that began in 2007 has led many observers to question the relevance of contemporary macroeconomic and finance theory for understanding outcomes and guiding policy. Many economists have also recognized that their portrayals of individual behavior and markets are deficient. But they have remained steadfast in their belief that they should continue to search for better, and even more complete, fully predetermined accounts of outcomes.1

To be sure, swings in housing, equity, and other markets, which are often blamed for the crisis, substantially eroded faith in the ability of financial markets populated by rational participants to allocate society's capital nearly perfectly. Nevertheless, Rational Expectations accounts of the intrinsic values of assets have continued to serve as the foundation for modeling swings in prices and risk. For example, in modeling asset-price swings, economists portray them as mechanical departures from REH-based, supposedly true values of prospects and companies.

Thus, as different as the “rational market” and bubble views may appear to be, they share the core assumptions of contemporary macroeconomic and finance theory. They both portray true intrinsic values with the Rational Expectations Hypothesis and characterize asset-price movements with fully predetermined models. As a result, both approaches—rational market models, with their stable prices around supposedly “true” fundamental values, and bubble models, with their portrayals of swings as departures from these values—yield distorted accounts of asset-price and risk movements in real-world markets.

REINVENTING IRRATIONALITY

A modern macroeconomic model's predictions concerning an asset price depend on its assumptions about the forecasting behavior of individual investors. As we have seen, Rational Expectations models assume that individuals act as if they all forecast according to the economist's own overarching model, whose predictions concerning the market price and those that it attributes to individuals are constrained to be one and the same. In contrast, mathematical behavioral finance models explore the implications of not imposing such model consistency and thus are widely interpreted as capturing departures from full rationality. But all overarching models, as Lucas (2002, p. 21) memorably put it, can be “put on a computer and run.” Thus, even as crude approximations, they are simply false explanations of economic outcomes, which are driven by nonroutine change.

Nowhere is such change more important than in financial markets. Thus, consistency between individual and aggregate levels in a fully predetermined model has no connection to rationality in real-world markets, and inconsistency within these models is not a symptom of departures from full rationality in those markets. The consistency of participants' fully prespecified forecasting strategies with an economist's representation of aggregate outcomes is, to put it bluntly, beside the point. Imputing such strategies to market participants merely presumes that everyone gives up looking for new profit opportunities.

To be sure, psychology and emotions are important for understanding how individuals make decisions, and behavioral economists have contributed important insights about such behavior. But because they formalize these insights with overarching mechanical rules, their models do not characterize departures from full rationality but are merely alternative portrayals of obviously irrational behavior.

BUBBLES IN A WORLD OF RATIONAL

EXPECTATIONS: MECHANIZING

CROWD PSYCHOLOGY

The notion that market participants may sometimes bid up an asset price far away from valuations based on fundamentals because crowd psychology and mania lead them to expect ever-rising prices has a long history in economics and the popular press.2 The so-called “tulip mania” in Holland in the 1600s and the South Sea bubble of the 1700s, which involved speculation in exotic types of bulbs and government debt, respectively, are often viewed as two of the best examples of a purely speculative bubble.

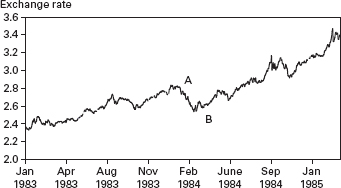

These episodes suggest that crowd psychology and manias may play a role in some markets now and then. But appealing to manias to explain price fluctuations in major asset markets, such as those for stocks, bonds, and currencies, suggests that long upswings are an aberration from otherwise normal times, during which the market sets asset prices at their supposedly true fundamental values. In fact, the long swings shown in Figures 5.1 and 5.2 are the norm, not the exception.

“Rational bubble” models ignore this observation and attempt to account for the dramatic upswings that sometimes characterize asset prices while preserving the Rational Expectations Hypothesis. In these models, crowd psychology can lead putatively rational individuals to downplay the importance of an asset's intrinsic value when forecasting future prices, even though they are assumed to have access to the supposedly true process governing this value.

In the simplest models, all investors sometimes come to believe that everyone else expects that, over successive periods, the asset's price will rise increasingly above what they all believe to be its intrinsic value. Partly because all market participants' forecasts embody this belief, it becomes self-fulfilling: the price moves steadily on average away from the hypothesized fundamental value. The Rational Expectations Hypothesis amounts to presuming that individuals act as if they possess an overarching model not only of an asset's intrinsic value but also of how crowd psychology actually develops when it takes over the market.

What might trigger individuals to think that crowd psychology has begun to influence an asset's price is left unspecified in the model. Presumably, a few successive price increases can lead to excitement and a sort of mania about the possibility that the price will continue to rise over an extended period of time.

All such bubble movements are assumed to end eventually. What triggers their collapse, as with what triggers their start, is usually not specified. The model merely presumes that some extraneous event causes the mania to dissipate. When it does, it is assumed to dissipate completely, thereby implying that the asset price immediately falls all the way back to its pseudo-intrinsic value implied by the Rational Expectations Hypothesis. Once a bubble bursts, then, the market is supposed to revert to setting asset prices nearly perfectly at their supposedly true values.

The validity of our argument that Rational Expectations models characterize grossly irrational behavior is not diminished when crowd psychology is incorporated into the analysis. On the contrary, it is difficult to fathom how anyone might forecast such an ephemeral phenomenon, let alone come to believe that it develops over time according to an overarching mechanical rule.

Like all REH-based models, the Rational Expectations bubble models also suffer from empirical difficulties. During a bubble, prices are supposed to rise steadily, save for a few random movements in the opposite direction. However, the dramatic upswings shown in Figures 5.1 and 5.2 all involve extended periods in which the asset price undergoes a persistent but partial movement back toward its benchmark value.

Consider the long upswing in the German mark-U.S. dollar exchange rate that occurred in the first half of the 1980s. By January 1983, the price of the dollar had begun to rise well above most estimates of its benchmark value. Over the ensuing two years, the exchange rate rose from 2.37 to 3.40, implying a further dollar appreciation of 44%. At its height, the dollar was overvalued relative to purchasing power parity by roughly 60%. Like most such dramatic upswings, economists and others referred to the dollar's rise as a bubble (see, e.g., Frankel, 1985; Krugman, 1986).

Figure 6.1 plots the daily German mark-U.S. dollar exchange rate during this supposed bubble, showing several periods in which the exchange rate moves persistently but partially back toward purchasing power parity. On January 9, 1984, for example, the market entered a nine-week period during which the dollar fell steadily, from 2.84 to 2.55 (points A and B in the figure). In fact, the dollar fell in eight of the nine weeks during this period. If the long upswing really had been due to crowd psychology and mania, it had surely dissipated by the beginning of 1984. But according to the Rational Expectations bubble model, the dollar should have immediately crashed to its fundamental value. No such crash occurred, and by mid-March 1984, the dollar had resumed its long upward climb.

Fig. 6.1. Swing in the German mark-U.S. dollar exchange rate, 1983-1985

Rational Expectations bubble models also fail to explain the long downswings that sometimes characterize asset prices. To begin with, while the downturns that follow the collapse of bubbles are supposed to involve a crash back to pseudo-intrinsic values implied by the Rational Expectations Hypothesis, these bubble models do not generate protracted movements below the pseudo-intrinsic values.3 There are, of course, episodes when prices fall by large magnitudes in the course of a single day—for example, the dramatic declines of U.S. equity prices on October 24, 1929 (“Black Thursday”), and on October 19, 1987 (“Black Monday”). But the long upswings depicted in Figures 5.1 and 5.2 are mostly followed by protracted downswings that last for years. For example, after U.S. equity prices reached their highs in September 1929 and March 2000 and began falling, they did not reach their lows until roughly three years later in both cases.4

The frequency, duration, and unevenness that characterizes the upswings and downswings that we actually observe in asset prices indicates that Rational Expectations bubble models do not provide even an approximate description of fluctuations in these markets.

A SEDUCTIVE NARRATIVE OF

BEHAVIORAL BUBBLES

Behavioral economists attempt to incorporate observation of how market participants actually behave into their models. They have recognized that, although collective manias may occur from time to time, price swings are an inherent feature of asset markets and thus cannot be explained on the basis of exceptional displays of crowd psychology. This observation has led them to seek less unusual patterns in decisionmaking to account for long swings.

One of the key findings emphasized in the literature comes from surveys of professional market participants concerning their trading strategies. These surveys reveal that the use of technical trading strategies is widespread, with many participants relying on them, at least in part, to make their trading decisions. Many of these so-called “chartist” strategies entail nothing more than extrapolating past price trends in one way or another (see Schulmeister, 2003, 2006). Consequently, formalizing the use of such strategies seemed like a particularly useful avenue for modeling asset-price swings.

Behavioral models also draw from the results of many controlled experiments in which payoff-relevant outcomes are uncertain. The results reveal that individuals' decisionmaking tends to deviate from what would be expected on the basis of standard probabilistic rules. These deviations often exhibit patterns. For example, when given new information, individuals tend to revise their beliefs about the likelihood of the uncertain outcomes slowly relative to what the laws of probability would imply, a phenomenon cognitive psychologists call “conservatism” (see Edwards, 1968; Shleifer, 2000). Psychologists interpret such patterns as suggesting that individuals rely on useful heuristics to aid them in making decisions in an uncertain world. In real-world markets, the tendency for a market participant to revise her forecasting strategy piecewise and moderately makes sense, given that which new strategy she should adopt is never clear.

And yet, while behavioral economists and psychologists have accumulated a massive amount of evidence showing that individuals do not act according to contemporary economists' standard of rationality, many of the behavioral bubble models use the Rational Expectations Hypothesis to portray the decisionmaking of a group of so-called “smart” or “informed” investors.5 By doing so, these models embody the same basic narrative that underlies the Efficient Market Hypothesis: if the market were populated solely by “intelligent investors” (Fama, 1965, p. 56), the price of the asset would roughly equal its “true” intrinsic value.

To generate bubble movements away from a model's pseudo-intrinsic values, an economist assumes the presence of so-called “irrational” or “uninformed” speculators. These individuals are “subject to animal spirits, fads and fashions, overconfidence and related psychological biases that might lead to momentum trading” (Abreu and Brunnermeier, 2003, p. 173). The forecasting behavior of the uninformed is often portrayed with one or more technical trading rules, which these participants use in a mechanical way and which extrapolate past price trends. This leads the uninformed to bid up prices, even though they may already be above the “smart” investors' assessment of intrinsic values.

By portraying the use of chartist rules as purely mechanical, behavioral economists transform what is a reasonable heuristic, which may supplement assessments based on inherently imperfect knowledge, into a strategy that is obviously incompatible with what anyone in real-world markets would consider even minimally reasonable behavior: participants supposedly never look for nonroutine change and remain forever faithful to their mechanical technical trading strategy.

LIMITS TO ARBITRAGE: AN ARTIFACT

OF MECHANISTIC THEORY

The insistence on overarching models leads to another difficulty. If it were really the case that smart investors roughly knew the “true” fundamental values of assets, they should be willing to wager large amounts of capital on any departures from these values. But if they did, they would bid prices to fluctuate randomly around their supposedly true values, implying that bubbles would not occur, despite the presence of uninformed or “less-intelligent” traders.

This difficulty has led to much research attempting to explain why smart investors do not always arbitrage away departures from the supposedly true intrinsic values. The literature on modeling so-called “limits to arbitrage” in a fully predetermined world has shown that if economists' smart individuals are risk-averse, they will voluntarily limit the amount of capital that they wager on the return of prices to their supposedly true intrinsic values.6The smart investors are assumed to know about the presence of the uninformed speculators, whose trading behavior increases the riskiness of investors' arbitrage positions. This risk further limits the size of these positions and enables the trading behavior of the momentum speculators to create a bubble.7

Economists have also looked at several institutional features of trading in real-world markets when modeling limits to arbitrage. For example, they have emphasized that all market participants face various capital constraints, which limit the size of both their long and short positions. Abreu and Brunnermeier (2003) assume such constraints as well as asymmetric information among their “rational” investors. In their model, momentum traders can create a bubble. The assumed information problem creates two types of smart investors: those who know that a bubble has formed and those who do not. Eventually, however, the price inflates so much that a sufficient number of smart investors become aware of the bubble, at which point the bubble bursts and the smart investors bid the price all the way back to its pseudo-intrinsic value. There is a possibility in the model that the smart investors who learn about a bubble early may not arbitrage a price's departure from its supposedly true fundamental value. Instead, they may initially bet on a continuation of the upswing in order to “ride the bubble though they know that the bubble will [eventually] burst” (Abreu and Brunnermeier, 2003, p. 175).8

THE TROUBLE WITH BEHAVIORAL BUBBLES

Of course, the need to model limits to arbitrage arises only because economists presume that asset prices unfold according to overarching mechanical rules, and that rational individuals somehow know the true process driving market outcomes. This core premise has led to an intensive search not only for institutional and other features of trading that motivate limited arbitrage but also for supposedly irrational heuristics and psychological biases that might justify the presence of mechanical momentum traders in bubble models.

There is no doubt that participants face capital constraints, and that some rely on technical trading and other heuristics. But by focusing on these issues, economists have missed the key problem facing market participants: the importance of nonroutine change and imperfect knowledge, which implies that even supposedly irrational behavior cannot be adequately modeled with fully predetermined mechanical rules.

Beyond their flawed foundations, it is difficult to reconcile behavioral bubble models with the long swings that we actually observe in asset markets. For one thing, the many models, such as that of Abreu and Brunnermeier (2003), that rely on asymmetrically informed smart investors to generate bubbles, are simply not credible explanations of outcomes in major asset markets, such as those for stocks and currencies. In these markets, a plethora of publicly available information is quickly disseminated around the world. Of course, company insiders have private information, and there may be isolated cases in which trading on such information influences a stock's price. But this scenario would not explain swings in broad stock-price indexes or currencies, such as those captured in Figures 5.1 and 5.2.

The Abreu and Brunnermeier (2003) model and many other Rational Expectations bubble accounts imply that once a bubble bursts, the asset price returns immediately to its supposedly true intrinsic value. But, as we have already seen, such an account does not provide even an approximate description of the downswings in financial markets.

Some behavioral bubble models do generate long-lived downswings. For example, in Frankel and Froot (1987) and De Grauwe and Grimaldi (2006), long swings away from pseudo-intrinsic values occur because all traders gradually switch over time between forecasting on the basis of an REH-based fundamental model and chartist rules. A long upswing in price occurs because market participants slowly abandon their fundamental model in favor of a chartist rule, whereas a long downswing arises because this process is eventually reversed.

Behavioral bubble models suggest that there is a relatively straightforward policy by which officials could deflate bubbles as soon as they begin. Instead of taking on the formidable task of fighting crowd psychology and manias, policy officials need only start a short-term price trend back toward the putative true fundamental value. According to behavioral models, this action would lead both chartists and smart investors to respond mechanically to the new trend, thereby reinforcing and sustaining it.

But this implication is contradicted by experience. One well-known example of the difficulty that policy officials face in engendering sustained countermovements in asset prices is provided by former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan's attempt to warn U.S. stock markets on December 5, 1996, of “irrational exuberance.”9 Initially, this pronouncement led to a sharp drop in equity prices. But if behavioral bubble models really captured the process driving equity values, this change in trend would have been more than sufficient to trigger a sustained reversal. Instead, U.S. stock prices resumed their upward trend, which lasted another four years.10

FORGOTTEN FUNDAMENTALS

Despite their apparent differences, the basic mechanism that underpins Rational Expectations and behavioral bubble models is essentially the same: upswings away from pseudo-intrinsic values arise because participants in the aggregate, for various reasons, increasingly downplay the importance of fundamental factors. Supposedly, then, fluctuations in asset markets are disconnected from movements of fundamental factors for long periods, implying that markets often grossly misallocate society's scarce capital. As we discuss in the next chapter and Chapter 11, this prediction is grossly inconsistent with the empirical record on asset-price fluctuations.

1For example, Krugman (2009) overlooked the possibility that economists' insistence on fully predetermined accounts of market outcomes should be reconsidered. Echoing a widely held belief, Krugman suggested that adding a mechanistic account of the financial sector to Rational Expectations maroeconomic models, as Bernanke et al. (1999) had done, would render such models relevant for understanding outcomes and guiding policy. For further remarks on this point, see footnote 17 in Chapter 1.

2For an excellent history of financial crises from this point of view, see Kindleberger (1996).

3Declining Rational Expectations bubbles are ruled out, because they have the potential to push prices to zero, which implies that such downswings could never get started.

4For an econometric analysis of the inability of Rational Expectations bubble models to account for price swings in currency markets, see Frydman et al. (2010b).

5Seminal behavioral bubble models include Frankel and Froot (1987) and DeLong et al. (1990b). For more recent models, see Abreu and Brunnermeier (2003) and De Grauwe and Grimaldi (2006). Frankel and Froot (1987) and De Grauwe and Grimaldi (2006) assume that all traders have access to what would be the true overarching model relating asset price to fundamentals in the absence of their use of chartist rules.

6See Gromb and Vayanos (2010) for a review of this literature.

7For empirical evidence that the importance of chartist rules and momentum trading is not nearly as great as is often believed and actually diminishes during the excessive phase of swings, see Chapter 7.

8Allen and Gorton (1993) show that agency problems and compensation structures based on short-term (quarterly or annual) performance also can lead portfolio managers, who supposedly know an asset's true value, to bet on a movement away from this level.

9Greenspan (2007) recounts the time leading up to and following his famous warning to the markets.

10Research on the efficacy of official intervention in currency markets also shows that policy officials face difficulties in influencing asset prices in any sustained way. Researchers have generally found that, although official intervention is effective in the near term at moving exchange rates in the desired direction, it does not usually lead to a sustained countermovement. For example, see Dominguez and Frankel (1993) and Fatum and Hutchison (2003, 2006).