1

The Invention of Mechanical Markets

ALTHOUGH THE raison d'être for financial markets implies that they cannot assess asset values perfectly, over the last four decades of the twentieth century, economists developed an approach to macroeconomics and finance that implied that financial markets allocate society's capital almost perfectly. To reach this conclusion, economists constructed probabilistic models that portray an imaginary world in which nonroutine change ceases to be important; indeed, it becomes irrelevant.

An economic theory of the world that starts from the premise that nothing genuinely new ever happens has a particularly simple—and thus attractive—mathematical structure: its models are made up of fully specified mechanical rules that are supposed to capture individual decisionmaking and market outcomes at all times: past, present, and future. As one of the pioneers of contemporary macroeconomics put it, “I prefer to use the term ‘theory'…[as] something that can be put on a computer and run…the construction of a mechanical artificial world populated by interacting robots that economics typically studies” (Lucas, 2002, p. 21).

To portray individuals as robots and markets as machines, contemporary economists must select one overarching rule that relates asset prices and risk to a set of fundamental factors, such as corporate earnings, interest rates, and overall economic activity, in all time periods. Only then can participants' decisionmaking process “be put on a computer and run.” But this portrayal grossly distorts our understanding of financial markets. After all, participants' forecasts drive the movements of prices and risk in these markets, and market participants revise their forecasting strategies at times and in ways that they themselves cannot ascertain in advance.

To be sure, with insightful selection of the causal variables and a bit of luck, a fully predetermined model might adequately describe—according to statistical or other, less stringent, criteria—the past relationship between causal variables and aggregate outcomes in a selected historical period. As time passes, however, market participants eventually revise their forecasting strategies, and the social context changes in ways that cannot be fully foreseen by anyone. The collapse of the hedge fund Long Term Capital Management in 1998, and the failure of ratings agencies to provide adequate risk assessments in the run-up to the financial crisis that began in 2007, shows that models assuming that the future follows mechanically from the past eventually become inadequate. Trading in financial markets cannot, in the end, be reduced to mere financial engineering.

ECONOMISTS' RATIONALITY OR MARKETS?

Ignoring such considerations, contemporary macroeconomic and finance theory developed models of asset prices and risk as if asset markets, and the broader economy, could be adequately portrayed as a fully predetermined mechanical system. And, recognizing that reducing economics and finance to engineering requires some justification, contemporary economists developed a mechanistic notion of rationality that they then claimed provided plausible individual foundations for their mechanical models.

Lucas hypothesized that the predictions produced by an economist's own fully predetermined model of market outcomes adequately characterizes the forecasts of rational market participants. The normative label of rationality has fostered the belief, among economists and noneconomists alike, that this so-called Rational Expectations Hypothesis (REH) really does capture the way reasonable people think about the future.

Of course, hypothesizing that any fully predetermined model can adequately characterize reasonable decisionmaking in markets is fundamentally bogus. Assuming away nonroutine change cannot magically eliminate its importance in real-world markets. Profit-seeking participants simply cannot afford to ignore such change and steadfastly adhere to any overarching forecasting strategy, even if economists refer to it as “rational.”1

The Soviet experiment in central planning clearly shows that even the vast and brutal powers of the state cannot compel history to follow a fully predetermined path.2 Change that cannot be fully foreseen, whether political, economic, institutional, or cultural, is the essence of any society's historical development.3

Such arguments were, however, completely ignored. Once an economist hypothesizes that his model generates an exact account of how an asset's prospects are related to available information about fundamental factors and adopts the Rational Expectations Hypothesis as the basis for “rational” trading decisions, it is only a short step to a model of the “rational market.”

Such a model implies that prices reflect the “true” prospects of the underlying assets nearly perfectly. An economist merely needs to assume that the market is populated solely by this sort of rational individuals, who all have equal access to information when making trading decisions. In the context of such a model, “competition…among the many [rational] intelligent participants [would result in an] efficient market at any point in time.” In such a market, “the actual price of a security will be a good estimate of its…[‘true'] value” (Fama, 1965, p. 56).

Economists and many others thought that the theory of the rational market provided the scientific underpinning for their belief that markets populated by rational individuals set asset prices correctly on average. In fact, this theory is the proverbial castle in the air: it rests on the demonstrably false premises that the future unfolds mechanically from the past, and that market participants believe this as well.

WAS MILTON FRIEDMAN REALLY UNCONCERNED

ABOUT ASSUMPTIONS?

Fully predetermined models presume that nonroutine change can be completely ignored when searching for adequate accounts of outcomes. These models offer an extreme response to the daunting challenge that such change poses for economic analysis. In contrast, relying on largely narrative analysis, Hayek, Knight, Keynes, and their contemporaries focused on the inextricable connection between nonroutine change, imperfect knowledge, and the pursuit of profit in capitalist economies.

As insightful and rich as these narrative accounts were, most contemporary economists probably felt that jettisoning them in favor of the clarity and transparent logic of mathematical models was a move in the right direction. After all, any explanation of the real world, let alone of the highly complex interdependence between individuals and the market, must necessarily abstract radically from its numerous characteristics. Even the detailed narrative accounts of Hayek, Keynes, Knight, and others left out many features of this interdependence.

But to instruct economists to embrace models that are constrained to portray capitalist economies as a world populated by interacting robots was not merely to call for more clarity and transparent logic in economic analysis. Economists were being asked to adopt an approach that went well beyond useful abstraction, because what it left out was actually the essential feature of capitalist economies.

Of course, most economists would readily agree that assuming away the importance of nonroutine change is not realistic. But they nonetheless cling to this core assumption in the belief that it transforms economics into an exact science. They also would agree that the Rational Expectations Hypothesis is not realistic, often describing it as a convenient assumption.4 When confronted with criticism that their assumptions are unrealistic, contemporary economists brush it off by invoking the dictum put forth by Milton Friedman (1953, p. 23) in his well-known essay on economic methodology: “theory cannot be tested by the ‘realism' of its assumptions.”

Our criticism, however, is not that the core assumptions of the contemporary approach are unrealistic. Useful scientific models are those that abstract from features of reality. The hope is that the omitted considerations really are relatively unimportant to understanding the phenomenon. The fatal flaw of contemporary economic models is their omission of considerations that play a crucial role in driving the outcomes that they seek to explain.

In fact, at no point did Friedman suggest that economists should not be concerned about the inadequacy of their models' assumptions.5 Indeed, at the time that he wrote his essay, examining assumptions was an important aspect of the discourse among economists. Friedman (1953, p. 23) recounted a “strong tendency that we all have to speak of the assumptions of a theory and to compare assumptions of alternative theories. There is too much smoke for there to be no fire”

Consequently, Friedman devoted substantial parts of his essay to an effort aimed at reconciling a “strong tendency” among economists of his time to discuss assumptions with his main conclusion that a theory cannot be tested by the realism of its assumptions. Using a variety of arguments and examples, he reiterated the essential point: an economist's success in devising a model that is likely to predict reasonably well crucially depends on the assumptions that are selected to construct it. As Friedman (1953, p. 26) put it, “The particular assumptions termed ‘crucial' are selected [at least in part] on the grounds of…intuitive plausibility, or capacity to suggest, if only by implication, some of the considerations that are relevant in judging or applying the model.”

The need to exclude many potentially relevant considerations is particularly acute if one aims to account for outcomes with mathematical models, which ipso facto make use of a few assumptions to explain a complex phenomenon. So the bolder an abstraction that one seeks, the more important it is to scrutinize the assumptions that one selects “on the grounds [of their] intuitive plausibility.”

Even more pertinent is Friedman's emphasis on the importance of understanding when the theory applies and when it does not. As he emphasizes throughout his essay, economists should scrutinize whether the assumptions they select are relevant in judging or applying the model.

Viewed from this perspective, the contemporary approach's core assumptions—that nonroutine change and imperfect knowledge on the part of market participants and economists are unimportant for understanding outcomes—strongly “suggest, if only by implication” that models based on them cannot adequately account for asset prices and risk. As we have seen, these assumptions imply that financial markets do not play an essential role in capitalist economies. Moreover, reliance on fully predetermined models and the Rational Expectations Hypothesis to specify decision-making assumes obviously irrational behavior in real-world markets (see Chapters 3 and 4). Friedman would surely consider assumptions that yield such implications unsuitable to serve as the crucial foundation of a theory that purports to account for how profit-seeking individuals make decisions and how modern financial markets set asset prices and allocate capital.6

Re-reading Friedman's essay makes it clear why he wanted to alert economists to the dangers of interpreting his methodological position as a lack of concern about the assumptions underpinning economic models. As a superb empirical economist, Friedman understood that basing economic models, as abstract as they must be, on bogus premises is a recipe for predictive failure.

For various reasons, contemporary economists typically do not mention the parts of Friedman's essay in which he acknowledges that careful selection and scrutiny of assumptions is the crucial aspect of building successful scientific models. Instead, they invoke a selective reading of his essay to justify their steadfast refusal to consider that the core assumptions underpinning their approach could be irreparably flawed.

It is not surprising that, as Friedman cautioned, models that place such assumptions at their core repeatedly failed what he considered the ultimate test of a good theory: its ability to provide adequate predictions. Nowhere is this failure more apparent than in asset markets. Indeed, after considering many empirical studies, Maurice Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff (1996, p. 625) concluded in their magisterial book on international macroeconomics that “the undeniable difficulties that international economists encounter in empirically explaining nominal exchange rate movements are an embarrassment, but one shared with virtually any other field that attempts to explain asset price data.”

Interestingly, however, this sober assessment—and the hundreds of studies that underpinned it—has not shaken economists' belief in the foundational principles of contemporary macroeconomics and finance. Despite their abject predictive record (indeed, despite the global financial crisis), fully predetermined accounts of economic outcomes are still held up as the only scientific kind, and the Rational Expectations Hypothesis remains the only widely accepted method for portraying how rational individuals forecast these outcomes.7

THE POST-CRISIS LIFE OF INTERACTING ROBOTS

One might have thought that the crisis that began in 2007 would have precipitated widespread questioning of the core assumptions of the contemporary approach to economic analysis. On the contrary, nearly all arguments about the causes of the crisis, and about the reforms needed to guard against the recurrence of such a catastrophe, take for granted the relevance of Lucas's conception of macroeconomics as a science of interacting robots whose rationality is based on the Rational Expectations Hypothesis.

Imperfectly Informed Robots

To be sure, insistence on fully predetermined models and the use of the Rational Expectations Hypothesis does not necessarily imply that the market sets asset prices at their supposedly true values—the key claim behind the so-called “Efficient Market Hypothesis”8 This implication of the Rational Expectations Hypothesis applies only if one assumes that all market participants have the proper incentives to search for the relevant information and are not somehow denied access to it. To preserve “rational expectations” and yet conclude that the Efficient Market Hypothesis is false, economists exploited the key distinction between information on fundamental variables, which serves as an input to the forecasting process, and the formal and informal knowledge that participants rely on to interpret that information and arrive at their forecasts.

In a seminal contribution to the Rational Expectations approach to the analysis of markets with informational imperfections, Grossman and Stiglitz (1980) pointed out that if all participants understood the supposedly true process driving asset prices, they would not devote the necessary resources to gathering information about the prospects of underlying assets.9 Thus, perfectly efficient markets (which, according to the Efficient Market Hypothesis, incorporate all available information into prices) are impossible.

Moreover, for various reasons, participants may not have equal access to information that is relevant to their decisionmaking. Formalizations of this idea in Rational Expectations models with so-called “asymmetric information” produce market prices that substantially deviate from the supposedly “true” values generated by their perfect-information analogs.10 These conclusions were generally viewed as providing the scientific underpinning needed to interpret important aspects of the crisis as stemming from distorted and asymmetric information, inadequate incentives, and imperfect market competition.

This helps explain why Rational Expectations models with asymmetric information have become ascendant in the public debate about the crisis that began in 2007. After all, woeful lack of transparency, glaring informational asymmetries, and distorted incentives for key market participants played significant roles in bringing the financial system to the brink of collapse.

Undoubtedly, Rational Expectations models with asymmetric information achieved “their aim [in showing] that the standard [Rational Expectations, ‘perfect information'] paradigm was no longer valid when there was even this seemingly small and obviously reasonable change in assumptions” (Stiglitz, 2010, p. 17). Such models' demonstration of the gross informational inefficiency of markets remains a profound conclusion—not because it is a statement about the real world, but because it shows that Efficient Market Hypothesis claim that markets are nearly perfect does not hold up even under the Rational Expectations Hypothesis.

Rational Expectations models with asymmetric information were widely thought to provide a scientific explanation of the severe informational problems exposed by the crisis that began in 2007. However, the claim that these models' conclusions are relevant for understanding real-world markets during the crisis is no less problematic than the Efficient Market Hypothesis claim—which rests on Rational Expectations models that assume away informational problems—that unfettered markets allocate capital perfectly.

Regardless of their informational assumptions, Rational Expectations models assume away the importance of nonroutine change and the imperfect knowledge that it engenders. Thus, if regulation and other measures could extinguish market distortions, the trading decisions of rational participants would result in asset prices that fluctuate randomly around their “true” underlying values, the truth being defined by how the economist's particular Rational Expectations model characterizes the process driving prices. Rational Expectations models with asymmetric information share with their orthodox perfect-information analogs—and also with behavioral finance models—this illusion of stability.

Asset-Price Swings as Bubbles?

Beyond colossal market failures, the crisis that started in 2007 highlighted another flaw of the Efficient Market Hypothesis: according to orthodox “rational market” models, excessive upswings in asset prices, such as those that occurred in housing and equity markets in the run-up to the crisis, should not really occur.11To be sure, as price swings were gathering momentum in the runup to the crisis, informational difficulties and other distortions in credit markets were apparent. But few would suggest that market distortions alone drive long swings in currency, equity, and other major financial markets around the world. On the contrary, in most respects, these large, organized exchanges are prototypes of the markets for which standard macroeconomic and finance theory was designed. They are characterized by a large number of buyers and sellers, few if any barriers to entry and exit, no impediments to price adjustments, and a plethora of available information that is quickly disseminated around the world. And yet asset prices in these markets often undergo long and wide swings that revolve around historical benchmark levels.

Linking Market Psychology to Fundamentals

The inability of Rational Expectations models to account for long-swing movements of asset prices and risk has not eroded the belief that an economist's Rational Expectations model adequately portrays the mechanism driving the true value of every asset. This belief has led economists to model long price swings in financial markets as departures from their supposedly “true” REH-based values. In keeping with the contemporary approach, they portrayed these so-called “bubbles” with mechanical rules, and assumed that if psychological considerations and other irrationalities could be eliminated, the market would return to its “normal” state: rational participants' trading decisions would result in asset prices that reflect the supposedly true prospects of projects and companies.12

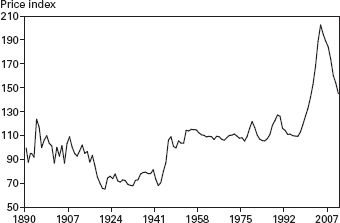

The kind of speculative fever envisioned by the bubble view of asset-price swings—with asset purchases reflecting only individuals' emotions and confidence that they can quickly unload their investments to the next fellow at a higher price—may play a role in some markets at some times.13 For example, evidence of such behavior can be found in real estate markets in several U.S. metropolitan areas, such as Phoenix and Miami, in the first half of the 2000s. As Figure 1.1 shows, housing prices in twenty metropolitan areas in the United States rose dramatically from the late 1990s to 2006. Accounts of this episode typically emphasize non-fundamental factors, such as emotions, get-rich-quick schemes, psychological biases (overconfidence), and house-flipping, which led individuals to bid up house prices (e.g., see Shiller, 2000; Cassidy, 2009). Indeed, the long upswing in Figure 1.1 is widely referred to as a “housing bubble.”

Fig. 1.1. U.S. real home price index, 1890—2009

Source: Data kindly provided by Robert Shiller.

Notes: The figure uses the Case-Shiller index, which is based on single-family home price indexes for the nine U.S. census divisions.

Many nonacademic commentators have interpreted such observations as providing vivid support for the view that asset-price swings are largely unrelated to economic fundamentals. Bubble models are widely considered to provide a scientific underpinning for this view. But these models overlook the key point: fundamental factors do play an important and pronounced role in driving asset-price swings, but their influence cannot be captured with mechanical rules.14

Fundamental considerations matter in two ways: they have a direct effect on individuals' forecasting and trading decisions, and they indirectly influence and sustain market psychology. Indeed, the key role of fundamentals is implicit in much of the discussion of the upswing in real estate prices in the run-up to the crisis that started in 2007. Although this upswing is usually referred to as a “bubble” and interpreted by many in purely psychological terms, some observers have also pointed out that the easing of credit, falling mortgage rates, and rising income levels during the 1990s and 2000s had direct effects on most individuals' decisions to buy and led to a sustained growth in market demand.

Behavioral economists focus on psychological factors in their attempts to explain why their “irrational” individuals ignore fundamentals. But this focus overlooks the important role that fundamental considerations play in sustaining market participants' optimism and confidence during the upswing.15 After all, if the trends in fundamentals had run in the opposite direction during the decade prior to 2007, the swing away from historical ranges of prices displayed in Figure 1.1 most likely would not have started, let alone lasted as long as it did.

The idea that fundamental factors can have an indirect effect on price movements through their influence on psychological factors was highlighted in a recent study of the U.S. housing market by Federal Reserve Bank of New York researcher James Kahn. He argued that the “resurgence in productivity that began in the mid-1990s contributed to a sense of optimism about future income that likely encouraged many consumers to pay high prices for housing” (Kahn, 2009, p. 1).

To be sure, the upswing in house prices in many markets around the country in the 2000s did reach levels that history and the subsequent long downswings tell us were excessive. But, as we show in Part II, such excessive fluctuations should not be interpreted to mean that asset-price swings are unrelated to fundamental factors.

In fact, even if an individual is interested only in short-term returns—a feature of much trading in many markets—the use of data on fundamental factors to forecast these returns is extremely valuable. And the evidence that news concerning a wide array of fundamentals plays a key role in driving asset-price swings is overwhelming.16

MISSING THE POINT IN THE ECONOMISTS' DEBATE

Economists concluded that fundamentals do not matter for asset-price movements because they could not find one overarching relationship that could account for long swings in asset prices. The constraint that economists should consider only fully predetermined accounts of outcomes has led many to presume that some or all participants are irrational, in the sense that they ignore fundamentals altogether. Their decisions are thought to be driven purely by psychological considerations.

The belief in the scientific stature of fully predetermined models, and in the adequacy of the Rational Expectations Hypothesis to portray how rational individuals think about the future, extends well beyond asset markets. Some economists go as far as to argue that the logical consistency that obtains when this hypothesis is imposed in fully predetermined models is a precondition of the ability of economic analysis to portray rationality and truth.

For example, in a well-known article published in The New York Times Magazine in September 2009, Paul Krugman (2009, p. 36) argued that Chicago-school free-market theorists “mistook beauty…for truth.” One of the leading Chicago economists, John Cochrane (2009, p. 4), responded that “logical consistency and plausible foundations are indeed ‘beautiful' but to me they are also basic preconditions for ‘truth.'” Of course, what Cochrane meant by plausible foundations were fully predetermined Rational Expectations models. But, given the fundamental flaws of fully predetermined models, focusing on their logical consistency or inconsistency, let alone that of the Rational Expectations Hypothesis itself, can hardly be considered relevant to a discussion of the basic preconditions for truth in economic analysis, whatever “truth” might mean.

There is an irony in the debate between Krugman and Cochrane. Although the New Keynesian and behavioral models, which Krugman favors,17 differ in terms of their specific assumptions, they are every bit as mechanical as those of the Chicago orthodoxy. Moreover, these approaches presume that the Rational Expectations Hypothesis provides the standard by which to define rationality and irrationality.18

Behavioral economics provides a case in point. After uncovering massive evidence that the contemporary economics' standard of rationality fails to capture adequately how individuals actually make decisions, the only sensible conclusion to draw was that this standard was utterly wrong. Instead, behavioral economists, applying a variant of Brecht's dictum, concluded that individuals are irrational.19

To justify that conclusion, behavioral economists and nonacademic commentators argued that the standard of rationality based on the Rational Expectations Hypothesis works—but only for truly intelligent investors. Most individuals lack the abilities needed to understand the future and correctly compute the consequences of their decisions.20

In fact, the Rational Expectations Hypothesis requires no assumptions about the intelligence of market participants whatsoever (for further discussion, see Chapters 3 and 4). Rather than imputing superhuman cognitive and computational abilities to individuals, the hypothesis presumes just the opposite: market participants forgo using whatever cognitive abilities they do have. The Rational Expectations Hypothesis supposes that individuals do not engage actively and creatively in revising the way they think about the future. Instead, they are presumed to adhere steadfastly to a single mechanical forecasting strategy at all times and in all circumstances. Thus, contrary to widespread belief, in the context of real-world markets, the Rational Expectations Hypothesis has no connection to how even minimally reasonable profit-seeking individuals forecast the future in real-world markets. When new relationships begin driving asset prices, they supposedly look the other way, and thus either abjure profit-seeking behavior altogether or forgo profit opportunities that are in plain sight.

THE DISTORTED LANGUAGE OF

ECONOMIC DISCOURSE

It is often remarked that the problem with economics is its reliance on mathematical apparatus. But our criticism is not focused on economists' use of mathematics. Instead, we criticize contemporary portrayal of the market economy as a mechanical system. Its scientific pretense and the claim that its conclusions follow as a matter of straightforward logic have made informed public discussion of various policy options almost impossible. Doubters have often been made to seem as unreasonable as those who deny the theory of evolution or that the earth is round.

Indeed, public debate is further distorted by the fact that economists formalize notions like “rationality” or “rational markets” in ways that have little or no connection to how noneconomists understand these terms. When economists invoke rationality to present or legitimize their public-policy recommendations, noneconomists interpret such statements as implying reasonable behavior by real people. In fact, as we discuss extensively in this book, economists' formalization of rationality portrays obviously irrational behavior in the context of real-world markets.

Such inversions of meaning have had a profound impact on the development of economics itself. For example, having embraced the fully predetermined notion of rationality, behavioral economists proceeded to search for reasons, mostly in psychological research and brain studies, to explain why individual behavior is so grossly inconsistent with that notion—a notion that had no connection with reasonable real-world behavior in the first place. Moreover, as we shall see, the idea that economists can provide an overarching account of markets, which has given rise to fully predetermined rationality, misses what markets really do.

1For a rigorous demonstration of this claim, see Frydman (1982). For other early arguments that the Rational Expectations Hypothesis is fundamentally flawed, see Frydman and Phelps (1983) and Phelps (1983). For a recent discussion and analytical results, see Frydman and Goldberg (2007, 2010a). For further discussion, see Chapter 3.

2Frydman (1983) formalized Hayek's (1948) arguments that central planning is impossible in principle and showed that these arguments imply the fundamental flaws of Rational Expectations models of market outcomes with decentralized information, such as those in Lucas (1973).

3For seminal arguments, see Popper (1946, 1957). Building on Frydman (1982, 1983) and Frydman and Rapaczynski (1993, 1994), we discuss in Chapters 2 and 3 the parallels between the contemporary approach to macroeconomics and finance, REH-based rationality, and the theory and experience of central planning.

4Even the most prominent critics of the orthodox theory of efficient markets use the Rational Expectations Hypothesis as a matter of “convenience.” See, for example, Stiglitz (2010), and our discussion below.

5Of course, on strictly logical grounds, Friedman's focus on the predictive test of a theory does not imply that he was arguing that economists should be unconcerned about their models' assumptions.

6Friedman's views on the relationship between the market and the state draw on Hayek's, and thus he held an ambivalent position on the Rational Expectations Hypothesis and its implications. Those who knew Friedman were aware that, on the one hand, he was not prepared to criticize this hypothesis. After all, it delivered the “scientific proof” that markets are perfect and that government intervention is undesirable and ineffective. On the other hand, Friedman (1961, p. 447) understood that fully predetermined models and the Rational Expectations Hypothesis were inconsistent with his argument that the state should not actively intervene because the effects of such actions are highly uncertain and “affect economic conditions after a lag that is long and variable.” In an interview with John Cassidy (2010a), James Heckman, Friedman's colleague at the University of Chicago at the time of the ascendancy of the Rational Expectations Hypothesis, recounts Friedman's ambivalence.

7In a recent interview published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Sargent (2010) has argued, rather unequivocally, that even the crisis has not undermined the broad consensus among macroeconomists concerning the usefulness of REH-based fully predetermined models. Recounting his visit to Princeton's Economics Department in the spring of 2009, Sargent (2010, p. 1) reminisced: “There were interesting discussions of many aspects of the financial crisis. But the sense was surely not that modern macro needed to be reconstructed. On the contrary, seminar participants were in the business of using the tools of modern macro, especially rational expectations theorizing, to shed light on the financial crisis.” See also Sims (2010).

8Strictly speaking, this claim is an implication of the Efficient Market Hypothesis, which postulates that asset prices reflect all available information. See Chapter 5.

9The argument runs roughly as follows: if some market participants did devote the necessary resources, others, who are presumed by the Rational Expectations Hypothesis to understand the true process through which this information is incorporated into prices, could glean the payoff from costly information simply by looking at prices. This free-rider problem would create a strong disincentive to gather information in the first place.

10For an overview of seminal contributions to the Rational Expectations approach to the analysis of markets with asymmetric information, see Akerlof (2001), Spence (2001), and Stiglitz (2001).

11Financial economists' attempts to reconcile the Efficient Market Hypothesis with the persistence and magnitude of the observed long swings have not been successful. See Chapter 5.

12In a book titled The Myth of the Rational Market, Justin Fox (2009) popularized the idea that the crisis had ended the myth of the rational market. But, as we noted in the introduction, contemporary market-failure and bubble models in fact perpetuate the belief that perfect markets are possible.

13Economists construct many types of bubble models, including those based on so-called “momentum trading.” See Chapter 6.

14To be sure, some behavioral finance models allow for fundamental considerations to influence prices. See Shleifer (2000). But even though these models purport to capture psychological considerations, they do so with fully predetermined non-REH-based rules. In addition to the oddity of representing psychology with mechanical rules, these models presume—as do all behavioral finance models—that psychology leads market participants to forgo obvious profit opportunities endlessly. See Chapters 6 and 7 for an extensive discussion of bubble models and the relative roles of fundamental and psychological factors in driving asset-price swings.

15Shiller (2000) and Akerlof and Shiller (2000) interpret psychological factors, particularly the notion of animal spirits, to suggest that market participants are irrational. However, in their narrative analysis of bubbles, they often discuss changes in fundamentals as triggering shifts in animal spirits.

16See Chapters 7-8 for an extensive discussion of the role of fundamentals in driving price swings in asset markets and their interactions with psychological factors.

17For example, in discussing the importance of the connection between the financial system and the wider economy for understanding the crisis and thinking about reform, Krugman endorses the approach taken by Bernanke and Gertler. (For an overview of these models, see Bernanke et al., 1999.) However, as pioneering as these models are in incorporating the financial sector into macroeconomics, they are fully predetermined and based on the Rational Expectations Hypothesis. As such, they suffer from the same fundamental flaws that plague other contemporary models. When used to analyze policy options, these models presume not only that the effects of contemplated policies can be fully pre-specified by a policymaker, but also that nothing else genuinely new will ever happen. Supposedly, market participants respond to policy changes according to the REH-based forecasting rules. See footnote 3 in the Introduction and Chapter 2 for further discussion.

18The convergence in contemporary macroeconomics has become so striking that by now the leading advocates of both the “freshwater” New Classical approach and the “saltwater” New Keynesian approach, regardless of their other differences, extol the virtues of using the Rational Expectations Hypothesis in constructing contemporary models. See Prescott (2006) and Blanchard (2009). It is also widely believed that reliance on the Rational Expectations Hypothesis makes New Keynesian models particularly useful for policy analysis by central banks. See footnote 7 in this chapter and Sims (2010). For further discussion, see Frydman and Goldberg (2008).

19Following the East German government's brutal repression of a worker uprising in 1953, Bertolt Brecht famously remarked, “Wouldn't it be easier to dissolve the people and elect another in their place?”

20Even Simon (1971), a forceful early critic of economists' notion of rationality, regarded it as an appropriate standard of decisionmaking, though he believed that it was unattainable for most people for various cognitive and other reasons. To underscore this view, he coined the term “bounded rationality” to refer to departures from the supposedly normative benchmark.