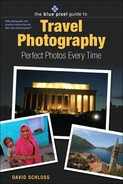

Chapter 1. Choosing the Right Gear

![]()

Right place, right time, right gear—a sunset along Trail Ridge Road in Rocky Mountain National Park. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

For every photographic trip there is the perfect balance of camera equipment. But most people find it impossible to know what gear to bring until they realize the item they desperately need is at home.

There are, however, a certain number of must-have accessories for the on-the-go photographer. Start with the basics—the digital photography tools you can’t do without. In this chapter I’ll discuss cameras, lenses, and computers, and what to look for in each category.

Figure 1.1. It’s possible to take too much gear on a trip, forcing you to spend all your time hauling equipment and deciding what to use. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

While digital technology revolutionized photography, if you’re a film shooter you’ll still be able to use most of these items. You can skip any item for reading digital media (compact flash card readers, for example) and you don’t need to bring your laptop (unless you want to watch a movie on the plane), but just about everything else still applies.

Selecting a Camera

All decisions about what to shove into a travel bag relate to your choice of camera. For most photographers, the camera is their most expensive and most important purchase. These days there are only two practical choices for the travel photographer—a point-and-shoot or a single lens reflex (SLR) (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Compact cameras (also called point-and-shoot cameras) have the advantage of small size. The larger SLR cameras offer more capability, but are also more expensive and heavier. (Photo by Bill Durrence)

![]()

The term point-and-shoot is a misleading—it’s used to refer to any compact camera without interchangeable lenses. An SLR camera is distinguishable from the point-and-shoot because it has interchangeable lenses. (Although some companies now make SLR cameras with a fixed lens and screw-on attachment lenses.) SLR cameras and specifically the cameras I’ll talk about in this book are increasingly based on a digital sensor instead of film, making them dSLR cameras.

Point and Buy

Many first-time travel photographers, in fact many first-time digital photographers, opt for point-and-shoot (aka “compact”). Compact digitals are lighter and smaller than their dSLR counterparts, they don’t have the hassle of interchangeable lenses, and they’re often seen as less intrusive (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. Compact cameras make it easy to shoot photos, like these buffalo along the road in Custer State Park. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

Cameras come in a variety of styles for three categories of users. A large, solidly built camera designed for the professional photographer is, not surprisingly, called a professional camera. On the other end of the spectrum are cameras that are less expensive, less durable, and often with fewer bells and whistles. These are called “consumer” cameras.

In the middle lies a group of photographers who want some of the features of a professional camera (faster shooting speed, improved durability, a few bells, some whistles) but don’t want to shell out for features they don’t need. These shooters are often referred to as “prosumers,” a horrible mashing of words that just means “a nonprofessional who wants some pro features.”

Pull out a big prosumer SLR (Figure 1.4) with a long lens, and chances are heads are going to turn But take out a compact camera, even in remote parts of the world, and you’re going to attract a lot less attention.

Figure 1.4. You won’t be inconspicuous if you’re using a big lens to take photos. (Photo by Corey Rich)

![]()

The biggest issue with point-and-shoots is their lack of flexibility. There’s less room to grow as a photographer with them since you can’t work your way up to better lenses and fewer accessories are available. A digital SLR often has interchangeable viewfinders, specialty lenses (such as macros and ultra-wide angles), lens-hoods, accessory strobes, and more. With a point-and-shoot, if you decide you want a wider-angle lens, or maybe a telephoto, you’re stuck with what you’ve got, and you’ll need to buy a new camera if you want greater flexibility.

Most digital point-and-shoots are equipped with a 3x zoom, providing a focal length equivalent to about 35-105mm. (See “Choosing a Lens” later in this chapter.) That’s not too shabby, but it leaves you without a wide-angle lens or a long telephoto lens, meaning you can’t capture wide landscapes or zoom in on a distant scene. Some models offer screw-on adapter lenses, but they are likely to produce photographs that are less sharp than ones taken with a single specialty lens.

Compact digitals are often slower than SLR cameras and are known to have a greater lag time, which is a measure of how long it takes between pressing the shutter release and having the camera actually capture a picture. With a long lag time you’re more likely to miss the perfect portrait shot as your subject moves, or capture a moving subject just a bit...too...late.

For the cost-conscious consumer, though, a top-of-the-line compact digital can be had for $600 to $1000, while a good digital SLR starts around that price. It’s best to choose a full featured point-and-shoot rather than a shirt-pocket sized camera, as those are mostly designed for convenience not image quality.

If you’re serious about getting good travel shots and opt for a point-and-shoot, you’ll want to make sure it has at a minimum these features:

• A durable body: Look for models that have metallic bodies and seem well built. If it feels light and flimsy when you hold it, it probably is.

• A good zoom lens: A 3x zoom is OK, but a 4x zoom is better. Some cameras have the term “wide angle” in their name, which means that their wide setting is wider than average. That’s great if you shoot a lot of landscapes, but you’ll sacrifice a bit on the telephoto side as a tradeoff.

• A high-resolution sensor: The minimum resolution you should look for is five megapixels. At that size you can enlarge pictures up to 8x10 while maintaining a high image quality. It’s a good baseline for shopping.

• A nice LCD screen: These built-in color displays are the center of the digital camera world. Make sure your camera’s screen is large enough to let you read the menus, and to see the photographs you’re composing.

• Lots of accessories: This might not be as essential to the new or casual photographer, but if you go the point-and-shoot route, look for models with such niceties as add-on lenses, filter attachments, and remote shutter releases.

There are some wonderful point-and-shoot cameras on the market, and most professional photographers I know wouldn’t be caught dead without at least a quality compact digital camera in their pocket, and they always have one for a backup when on the road. If you’re traveling with a point-and-shoot, you can still grab great pictures (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5. This photo of Opatija, Croatia was taken while walking back to the hotel after dinner, using a small point-and-shoot digital camera. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

Some of the most familiar names in photography—Nikon, Canon, Minolta, Olympus, Pentax, and others—make incredibly powerful point-and-shoot cameras, but some lesser known companies also offer great bargains. Don’t be afraid to look for cameras from Sony, Panasonic, Kodak, Casio, Samsung, or from any company that’s better known for making things like microwaves and radios than camera gear. The technology used inside a digital camera is remarkably similar to that used in an MP3 player or any other bit of electronics, so some newcomers to photography are making a name for themselves.

The Singular, Handy Single Lens Reflex

An SLR has a number of advantages over a compact point-and-shoot. The interchangeable lenses make it easy to compose your photograph in a variety of ways, and the camera’s metering and shutter systems are usually more advanced. SLRs universally have a flash hot-shoe that enables them to make use of sophisticated add-on systems.

As with the point-and-shoot camera, the SLR market is crowded, and you want to make sure you get the most for your money. Solid SLR cameras are made by Nikon, Canon, Konica-Minolta, Olympus, Pentax, and others, all of whom offer dependable bodies starting at around $900. Here are some features to look for:

• A durable body: An SLR has a lot of moving parts and you don’t want to damage them by dropping or banging the camera. At the $900 price point you’ll be hard pressed to find a body with a solid metal frame—those usually appear in the neighborhood of $1500. But be sure the model you choose feels solid.

• A good selection of lenses: Companies such as Canon and Nikon have dozens of lenses for their systems, and their cameras work with compatible lenses from companies like Sigma and Tamron. Other systems have a more limited range of optics, but that might not be an issue if you’re never going to buy a $2000 professional lens. Make sure your system has a good selection of both consumer and prosumer lenses before you commit. (See “Choosing a Lens” later in this chapter.)

• The right resolution sensor: Generally speaking, entry-level digital SLR cameras have a higher resolution than most high end point-and-shoot cameras, though this isn’t always the case. If you’re comparing a five-megapixel compact against a five-megapixel SLR, keep in mind that the SLR’s sensor probably produces a cleaner, more accurate image. That’s part of what you’re paying for.

• A decent LCD screen: In order to save money, digital SLR manufactures often put slightly lower-quality LCD screens into SLR cameras than into compacts because you do your composition and focusing through the viewfinder of the SLR, only turning to the screen for menu choices and the occasional image review. On the other hand, with a point-and-shoot, you use the LCD for everything from composing your photo to changing your settings. It’s OK if your SLR has a relatively small LCD. Just make sure it’s bright enough to see in daylight and large enough to get an idea of how your image turned out.

• TTL strobe system: A big advantage of SLRs is that they can use accessory strobes—flash systems that mount to a hot-shoe on the camera and work with the SLR to ensure a properly exposed picture (Figure 1.6). The process of making sure the strobe produces just the right amount of light is complicated and is usually achieved through a system with TTL in the name (that stands for Through The Lens, a type of flash metering, though different companies call their systems by different names like iTTL or eTTL.)

Figure 1.6. The display on the back of this Nikon SB-800 Speedlight indicates that it’s functioning in TTL mode, helping attain more accurate flash exposures. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

• Lots of accessories: Just as with the point-and-shoot, you want a system that has lots of accessories. All of the big names in cameras have tons of accessories available—more, in fact, than the average photographer knows what to do with.

Digital SLR cameras that come with a price tag up to about $1000 usually fall into the “consumer” range. They often sacrifice features (things like autofocus speed, sensor resolution, or durability) in order to hit a sweet spot that allows aspiring photographers to get good pictures without breaking the bank. If you’re unsure of your interest in photography, don’t spend more than this amount on your first camera. But if you think you’ll advance in the future, choose a system from a manufacturer that also makes more sophisticated (and more expensive) equipment so that you can keep your investment in lenses and accessories when you upgrade your camera body.

Sometimes you’ll hear the term “35mm digital” used to describe digital SLR cameras. But “35mm” can only be applied to cameras that shoot film, since that term signifies the size of the film used in the camera (and digital cameras don’t have film). Lots of companies have kept the term around, however, to make consumers feel more comfortable with the switch to digital.

SLRs that cost $1000 to $2500 are often called “prosumer” cameras (Figure 1.7). These cameras are faster, more solid (they’re usually made of sturdier materials), and more reliable in the long run. A good prosumer digital camera will serve you well for years. For those willing to go all-out there are the true professional bodies, with prices starting around $2500 and going up to nearly $10,000 (Figure 1.8). While these are the most durable, sophisticated, and impressive cameras on the market, they can really do more to confuse than to aid the new user. A pro camera can have a dizzying array of buttons and switches, and can weigh as much as five pounds.

Figure 1.7. Canon’s EOS Digital Rebel was the first “prosumer” digital SLR to sell for under $1000, including a lens. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

Figure 1.8. The Nikon D70s, left, costs less and has fewer features and buttons, but it’s easier to learn to use than Nikon’s top of the line digital SLR, the D2X, right. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

When selecting a camera, keep in mind that for any trip lasting more than a few days, it’s essential to have a backup even if you’re traveling to a region with lots of electronics stores (Figure 1.9). It’s important to know how your camera works, and you don’t want to be fumbling with the controls on a replacement camera. Having a backup also allows you to shoot a scene using two different lens focal lengths without having to change settings.

Figure 1.9. Taking a second camera along will let you work faster without having to change lenses, and can also prevent a photo trip disaster if one camera fails. (Photo by Bridget Fleming)

![]()

Pros often take two top-of-the-line bodies (or one pro body and one prosumer body), but the budding travel photographer can easily get away with a main body and a point-and-shoot. Budget accordingly—that once-in-a-lifetime safari might warrant two prosumer cameras. For versatility when traveling, it’s best to shoot with a SLR.

If you’re close to a major city, you can often rent a camera body for a trip. It’s cheaper to spend a few hundred dollars renting a second body thanto buy one just for a safari or extended vacation.

Choosing a Lens

A good photographer can compensate for a camera body that lacks some features, but there’s no way to overcome the poor image created by a cheap lens. Photography is all about the image, and there’s nothing worse than having a very expensive camera connected to a low quality lens. No matter how much you spend on your camera body, if the light coming through the front of the camera is distorted by a poorly made piece of glass, you’re going to get an image that’s sure to disappoint.

The variety of lenses on the market is stunning and the range of choices can make it difficult to choose the right lens for a given situation. A quick overview of some terms can steer you toward the perfect choice.

Understanding Focal Length

A lens’s focal length is provided in millimeters and is a measure of how much of a scene a lens can view. It’s easier to think of it as the amount of magnification applied to a subject with larger numbers indicating more magnification.

A standard lens (from about 35mm to 85mm) creates an image that closely approximates the view of the human eyes (Figure 1.10). These lenses are great for portraits, shots of details on a building, close-ups of animals, and more. Most photographers consider standard, or “normal,” lenses their workhorses.

Figure 1.10. Popular “normal” lenses today tend to be zooms that cover the middle range, like this Nikon 18-70mm. They make good all-purpose lenses, with the ability to cover both wide-angle scenes and those needing a short telephoto. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

Lenses break down into a these categories: wide angle, standard, telephoto, and super telephoto. A lens might be 24mm (wide angle) or 200mm (telephoto), for example.

In 35mm cameras (and in cameras listing the equivalent), lenses from 10mm to around 35mm are wide angle. These lenses are great for landscape shots, portraits of people or places that need to show a lot of what’s going on, or special effects for exaggerating the sizes of objects or their distances (Figure 1.11). A wide-angle lens is the one you’ll want for photographing a range of lions on the African plain, or for the portrait of a family reunion (Figure 1.12).

Figure 1.11. A fisheye lens lets you make a very different type of photo, circular with black sides and distortion at the edges. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

Figure 1.12. You can make beautiful photos with extreme wide-angle lenses, but be aware of the curvature that will happen at the edges of the frame. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

Figure 1.13. These colorful mailboxes represent the character of Vancouver and were shot with a short, normal lens. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

Figure 1.14. Many people find a compact telephoto zoom lens, like this 75-300mm from Canon, to be the perfect second lens to carry. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

A telephoto lens (85mm to around 200mm) works like a telescope for your camera, making things look larger than life (Figure 1.15). These lenses are perfect for capturing distant objects so that they don’t look like tiny specs and for near-distance photography where you want to isolate small details (Figure 1.15).

Figure 1.15. A telephoto lens was used to compress this market scene in Eastern Europe and add to the feel of color and crowding. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

A super-telephoto lens (anything longer than 200mm) is a specialized lens designed to photograph super-distant objects (Figure 1.16). Super-telephoto lenses tend to be heavy and expensive, so most photographers usually carry them only when the subject warrants their use.

Figure 1.16. Super telephotos tend to be those longer than 300mm, like this Nikon 80-400mm Vibration Reduction zoom, and give the photographer much more “reach.” (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

It’s important to get a lens or lenses that are the right focal length for the types of photographs you plan to make. It’s hard to shoot an eagle nesting in a tree with nothing but a wide-angle lens, and it’s equally hard to capture a panoramic shot with a super telephoto.

Deciding on a Zoom or Prime Lens

Most people have heard of a zoom lens—it’s one that lets you change focal lengths by turning a dial on the lens or pulling and pushing on the lens barrel (depending on the design.) Zoom lenses are versatile because they let you carry around a range of focal lengths without needing a bagful of lenses.

The opposite of a zoom lens is called a prime lens, and it has only one focal length. Because there are fewer moving parts in a prime lens, most prime lenses can be built to a higher quality than a zoom lens. Prime lenses are often less expensive than zooms (though less versatile), and usually produce a slightly better image at the same focal length. If your shooting style works with prime lenses (if you’re OK moving toward and away from your subject rather than zooming), then you can sometimes save money picking a prime instead of a zoom.

The Importance of the Lens Aperture

Inside a lens is a small diaphragm that allows light to pass through to hit the digital sensor. The opening in the diaphragm is called the aperture and is referred to with a number that’s known as the camera’s f-stop. A low f-stop indicates a wider opening that lets in more light; a high f-stop indicates a smaller opening that lets in less light. When the lens is set to a low f-stop, some of the photograph will be out of focus. When that lens is at a high f-stop, more of the picture will be in focus (Figures 1.18 and 1.19).

Figure 1.18. A long telephoto, in this case 400mm, lets the photographer get close-ups of wildlife without having to put themselves or the animals in danger. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

Figure 1.18. Using a small aperture, in this case f/11, means the depth of field will be increased, allowing more detail in the foreground and background. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

Figure 1.19. Using a wide aperture, in this case f/2.8, means the depth of field will be minimal, keeping the sharpness just to the subject and blurring the background. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

This has to do with the way beams of light travel before hitting your imaging sensor, and involves complex physics and optics. Suffice it to say that at a low-numbered f-stop there’s a bigger opening for light to get in, allowing light rays to come from different angles and creating blurriness in your photo. When you’ve got the camera at a high-numbered f-stop, there is a smaller opening, which forces all the light rays to hit the same point, so less blur.

In other words, when you use a lower f-stop, less of your photograph will be in focus; use a higher number, more will be in focus. If you take a picture with your camera set to f/2.8, there might be only two inches of depth of field. (The exact depth of field depends on the particular lens and the distance to your subject.) Focus on someone’s nose, and their ears will be slightly blurry, their shoulders even more blurry, and the background completely out of focus.

Take that same lens and that same subject and set your lens to f/22 and, when you focus on your subject’s nose, not only will it be in focus, but so will the ears, shoulders, and anything in the distance.

From a practical standpoint this means that the f-stop is crucially important in capturing the photograph you want. Let’s say you’re looking to take a photo of a local merchant, but the only background is ugly and distracting. Selecting a low f-stop will blur the background, leaving just the person in focus.

But if you want to capture not only that person but also the stall behind the person and the bustling nature of the market, you’ll choose a higher f-stop.

f-stop is pronounced “eff stop” and is written f/XX where XX is the number of the aperture setting. Because this number has to do with optical science it’s often not a whole number. What you end up getting is a number such as f/2.8 (pronounced “eff two point eight”)

In addition to its aperture, your camera also has a shutter, which is a small Venetian blind-like mechanism that opens and closes to let in light. The amount of time the shutter is open is usually measured in fractions of a second. A photo might be taken in 1/125th of a second, for example.

The less time the shutter is open, the more your pictures will seem to “stop” motion, freezing your subject. The longer it’s open, the more likely your photos will have a motion blur.

The tricky thing is that the shorter the amount of time the shutter is open, the more light you need to take your photo (because light has less time to hit your sensor). In a dark scene, you can take a photo with a longer exposure time to let in more light, but moving subjects will appear blurry. Any movement you make while the shutter is open for a long time will blur your photograph.

This is also the case when using a higher f-stop, because the aperture lets in less light at a higher setting than it does at a lower setting. Shutter speed and f-stop correlate. Each time you move your aperture setting one number higher, you’ll need to double the amount of time the shutter is open, and vice versa.

As a result, even if you’re shooting in daylight, if you set your camera to, say, f/22 (to get an entire landscape in focus, for example) you may need to stabilize the camera with a tripod or similar support.

Remember that tripods save the day. You don’t have to worry so much about your shutter speed if you’ve got your camera mounted on a stable tripod. Blurry pictures, be gone!

It’s all a big game of compromises and pocketbooks. If you’ve got deep pockets, you could get the top-of-the-line lenses in every category, but you’ll probably need an assistant to carry everything for you. See “Deciding of the Perfect Gear for You” below for some recommendations based on what the pros carry.

Special Considerations

Many manufacturers use special coatings on the lenses and special designs to prevent light from causing distracting lens flares or other distortions. The companies usually use letters in the name of the lens to indicate this. You might see that a company makes a 50mm f/1.4 and a 50mm f/1.4 APO lens (which is short for “apochromatic,” meaning “doesn’t distort your images”), with the latter one being more expensive and higher quality.

A very recent development is the use of an internal gyroscope designed to compensate for hand-shake or other blur-inducing movement. At first I was skeptical, but now I’ve come to love these systems, often called Vibration Reduction (VR) or Image Stabilization (IS). They allow photographers to shoot in much lower light (Figure 1.20). Naturally stabilized lenses cost more.

Figure 1.20. This shot wouldn’t have been possible without the lens’s built-in vibration reduction feature. Hand-held, the photo was shot at 1/6 of a second with a Nikon 70-200mm f/2.8 zoom. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

Deciding on the Perfect Gear for You

I bet you thought I’d end this discussion of cameras and lenses with advice on exact models to buy. Sorry, but there’s no single solution for travel photography.

Any choice you make will involve compromise. If you take several expensive lenses, you’ll carry around more weight than is comfortable or practical. If you pick only one or two lenses, you might have to settle for designs that don’t have APO coatings or don’t have a low f-stop number.

Most professionals have an arsenal of expensive cameras and lenses used in the studio and on professional jobs. If pros are traveling and want to bring along their cameras, they’ll usually turn to a second set of cameras and travel lenses with more range but more compromises too. The goal is to pick a few good lenses that can do the job of the working lenses, but with less weight.

In the next chapter I’ll discuss different packing styles for the travel photographer. First, to give you some idea of what cameras and lenses to take when on your trip, let’s look inside the bag of a Blue Pixel photographer. Remember, what works for one person doesn’t work well for another, but this a good starting point for lens shopping.

Armed with an idea of the type of photographs you’d like to take and the areas to which you’re traveling, a good photography store salesperson should be able to suggest specific lenses to fit your needs. Nothing beats the ability to get your hands on some lenses and try them out.

INSIDE BILL DURRENCE’S BAG

Bill Durrence has traveled the world as a professional photographer. These are the tools he packs.

![]()

Becoming Computer Literate

Digital photography requires significant computing power. While you might not need the most expensive computer, you’re going to want a nice machine on which to view, sort, and share your images. (See Chapter 7 for more on photo sharing.)

You might not always travel with your computer (thought most pro photographers do), but when you get back home you’re going to want a lot of computing muscle to work on those copious files you’ve generated.

Avoid the bargain-priced entry-level systems offered by many companies. Instead look for a computer that’s advertised as being at least in the middle of a company’s lineup. While computer specifications change almost monthly, a consumer-level photographer will probably end up spending just over $1,000 on a system, while a prosumer might spend a bit over $2,000, and a pro from $3,000 to $8,000.

Sure there are printers on the market with slots for your digital storage cards, allowing you to print without using a computer, but that’s really just a novelty. A computer gives you a place to edit your images, store them, back them up, share them, and print them.

It might feel cumbersome to bring a computer on the road—even a laptop—but it’s the best way to check your images to make sure that you got the shots you want (Figure 1.21). Plus, with free wireless Internet connections all over the world, you can send people photos of your trip to Europe while you are still on your trip.

Figure 1.21. Taking a laptop computer along means one more thing to pack and carry, but it is worth the trouble for digital photographers. You’ll be able to download your images, make sure you’re getting the photos you want, and back up the photos before returning home. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

If you’re going on a trip where you can’t take your computer, you can use a portable storage device to transfer your images while you’re on the road (Figure 1.22). You can even use some of them to burn a CD. The problem is that they’re usually almost as heavy as a laptop computer, and they don’t provide any way to edit or manage your images while you’re away from the office. (See Chapter 6 for more information on in-field naming, and why it’s a good idea to bring a computer.)

Figure 1.22. The other option for downloading images while on a trip is to use a digital wallet device, like the Flashtrax by SmartDisk. (Photo by Michael Schwarz)

![]()

Companies like Nixvue, Delkin, Epson, and others make portable devices that act as both card readers and data storage devices.

Computers advance at a rapid rate. A great rule of thumb is to look for computers that are advertised for hard-core computer gamers, or video editors. Both these user groups require a lot of horsepower to get the job done. Some key things to look for when shopping are:

• Processor: It doesn’t matter if you’re shopping for a PC or for a Mac, all computer manufacturers have different models powered by different levels of processors. The speed rating of a computer isn’t as important as you’d think. Shop for computers within the different levels. You might not need the fastest class of processor on the market, but as a digital photographer you should probably avoid the slowest machines.

• Optical burner: Most computers these days come with CD or DVD burners. A DVD burner will suit you better in the long run—you’ll be able to squeeze more backup images onto a single disc.

• RAM: Many people overlook the amount of memory in their computers, sticking with the amount of RAM installed by the manufacturer. But most companies put in just enough RAM to allow the computer to perform basic functions. It’s not uncommon these days for a computer to have more than 1GB of RAM. Get one gig of RAM at minimum, and if your computer can accept more, get more.

• Interfaces: Your computer needs to communicate with the rest of the world. Be sure the system you buy has at least a USB 2.0 port and a FireWire port (though some PCs will have only USB 2.0, that’s fine since all but some pro digital cameras have USB 2.0), wireless connectivity, and Ethernet ports.

If you’re traveling with a laptop, you’ll want to gear up on accessories, too. Make sure you’ve got the following before you go:

• Security: Essential for locking up your computer in a hotel room (they’re not foolproof, so don’t leave your computer anywhere that’s not reasonably safe). A good insurance policy is crucial too. Most home-owners and rental policies cover computer and camera items, but you might need a separate rider, especially if you’re traveling.

• CDs and/or DVDs: Necessary for backups (which you can send home) and for image storage.

• Cables: Make sure you’ve got the right cables for your camera, card reader as well as generic FireWire and Ethernet cables.

• Installation CDs: If there’s any time you don’t want your computer to crash, it’s when you’re on the road. And thanks to Murphy’s Law, that’s exactly when your hard disk will need to be reformatted. Bring copies of the installer CDs for your operating system and your crucial applications, along with serial numbers for the installation.

• Electrical adapters: Most laptops work on any voltage from 110-220, so you’ll need plug adapters to keep computing in any country.

Moving Your Photos from Camera to Computer

You’ll also need some way to get your images from your camera into your computer. The best way to do this is with a FireWire or USB 2.0 external card reader (Figure 1.23). Moving pictures over with the cable that came with your camera drains the battery in your camera. Using an external card reader ensures the fastest transfers and maintains battery life.

Figure 1.23. An external card reader is a must for getting images into the computer quickly and efficiently. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

Improving Your Memory

Manufacturers ship new digital cameras with anemic memory cards. Before you leave on your trip, buy a few high-capacity cards (Figure 1.24). A five-megapixel camera can shoot a few hundred images with a 1GB storage card, but only three or four images with the 16MB card that comes in the box.

Figure 1.24. The rule of thumb is to buy several cards for your camera, and the largest sizes you can afford. (Photo by Reed Hoffmann)

![]()

You’ll want a few cards so that you can keep shooting even after you’ve filled up a card with great travel images. You’ll also want to make sure you’ve got enough cards to keep taking pictures if you lose one or it stops working.

Accessorizing Yourself

Understanding the basics of camera and lens technology is only the first step in selecting your perfect travel gear, but it’s the most important step. In the next chapter we’ll examine the rest of the travel photographer’s essential gear, and talk about packing and traveling techniques.