CHAPTER 14

Producing the Television Newscast

CONTENTS

Producers—Definitions and Skills

The Logistics and Strategies of Producing

Technical Aspects of Producing

In-Class Exercise: Creating a Newscast

KEY WORDS

Ad-Libs

Associate Producer

Back Timing

Balancing the Anchors

Blocks

Bumps

Clusters

Executive Producer

Field Producer

Gatekeeper

Kicker

Leads

Line Producer

Live Shots

News Hole

Peaks and Valleys

Teases

Toss

Web Producer

INTRODUCTION

By following this text, we’ve acquired the news, written the copy, and reported the story. However, even those who only want to report, shoot, edit, or anchor must be keenly aware of the producing process. A reporter may shape an individual story, but it is the producer who frames the entire newscast.

Producing is an exceptionally difficult art. The time constraints are brutal: A 30-minute newscast contains eight minutes of commercials, leaving only 22 minutes for news. Subtract three minutes for your weather report (19 minutes remain), another four for sports (now 15 minutes are left for news), and then another minute for bumps, opens, and closes. Your half-hour of news lasts a mere 14 minutes.

Another problem facing producers is they serve as the final gatekeeper, which is a person who allows or denies a news story to get on the air. The gatekeeping process starts with the assignment editor, who may or may not bother sending a crew to cover a story. Gatekeeping continues in the field with the videographer —remember, any time you point a camera at one subject, you effectively point it away from all others. A reporter filters the news as well, picking one interview over another. The person editing the story then truncates the footage into a manageable running time, excluding excess footage. By the time the story is finished, it still must be approved by the producer.

FAST FACT: Gatekeeping was first associated with news selection in David White’s groundbreaking article “The Gate Keeper: A Case Study in the Selection of News” in 1950.

An interrelated problem for producers is dealing with the personalities of those in the newsroom. The sports reporter may want more time for a compelling local event, whereas the investigative reporter may demand an extra 30 seconds for a lead story. Anchors want to be on the air. This is not merely their egos talking, because if the station’s management is paying an above average salary, they want to see their anchors frequently. Finally, television news reporters expect to see themselves on the air, crave the occasional live shot, and appreciate being called onto the set for a “live toss” to their news report. Producers must deal with these factors constantly, juggling times, deadlines, the competition, and a score of easily bruised egos. Facing these challenges is daunting enough, but for television producers, their success or failure is witnessed on the air every day.

At the close of this chapter, we’ll look at how news stations are using web producers to send the news online. As the newscast producers concentrate their efforts into getting their programs on air, the news is fed to the station’s web producer, who is responsible for getting the stories onto the Internet. This specialized position is proving invaluable for newsrooms as more news consumers search for their information online.

PRODUCERS— DEFINITIONS AND SKILLS

Most TV news producers will tell you that they are the creative force that makes the difference between a good newscast and a poor one. It’s hard to argue with them. Producers lay out the newscast, decide what stories will lead the newscast, and determine the flow of the rest of the stories so that they best hold the attention of the viewers. Producers also play an important role in deciding how to use the video and sound bites that are available to them and their reporters and how to best work them into the newscast to maintain a maximum of interest. Each producer brings his or her own particular skills and abilities to the process and gives each newscast has a different look. The battle for viewers is intense.

FIGURE 14.1 DeshaCAM/Shutterstock.com

Assistant News Director Robbyn DeSpain of KFVS12 says:

The most important role of a producer is to put a newscast together that has urgency, importance, and good content. The biggest opponent we have is the many other options available for someone deciding whether to watch the news. We’re trying to keep the viewer from hitting the off button on the remote control. That’s why breaking news, breaking weather, or that big investigative piece are always right at the top of the show. We’ve got to hook the viewer to keep them watching. I also use teases to try and entice my audience to stick around for that promotable story in my second or third block. You’ll notice that the important seven-day weather forecast is often far down in the show. That’s intentional, to keep viewers and ratings as long as possible.

The success of television news programs, regardless of whether they are at the network or local level, depends not only on the quality of the news gatherers, reporters, and videographers, but also on the ability of the producer, the executive producer, and the line producer. Producers determine not only what goes into the nightly news, but also how much time is devoted to each story and in what order the stories will appear.

No two producers would create exactly the same newscast, just as no two writers or reporters would write or report a story the same way. However, there are certain rules and philosophies about the production of a newscast. You have read about the differences and similarities in style and philosophy in writing and reporting throughout this book. This chapter discusses the thinking of producers on news and how they put their newscasts together. We’ll begin by illustrating how producers are used differently in various stations. Note that some stations use titles such as senior producer or assistant producer instead of those listed below. This is an in-house decision but it does not impact the duties of a position; it is simply a different job title.

Executive Producer

The executive producer is responsible for the long-term look of the newscasts. He or she determines, in consultation with the news director and the station’s general manager, the set, the style of the opening and close, the choice of anchors, the philosophy, and other details. The executive producer reports directly to the news director. If there are problems with the newscast, the executive producer will have to do some explaining after the show. Of course, the executive producer will review the problem with the line producer before the news director calls. If the ratings slip, the executive producer must explain why and try to fix the problem. Otherwise, he or she may be looking for another job.

Line Producer (Show Producer)

On a day-to-day basis, the line (or show) producer is mostly responsible for deciding what goes into the news broadcast and making sure it’s ready to air. The executive producer and news director will watch in the wings, but most of the responsibility for preparing the individual newscasts is given to the line producer. He or she prepares the rundown (lineup), which outlines which packages, voiceovers, and readers will appear in the show, in what order they’ll appear, and how much time will be devoted to each story. If there is any doubt about which story should lead the newscast, the line producer may consult with the executive producer or the news director. This consultation also applies to any problem that cannot be resolved simply.

The line producer works closely with the assignment editor and reporters. They talk about the rundown, reporter assignments, the angle the producer wishes the stories to take, story times, and whether the story is used as a package or a voiceover. As the day progresses, the line producer updates the rundown to reflect any breaking stories. If the producer has a special liking for a story, he or she tells the assignment editor and a reporter is assigned to the story. Sometimes the producer and assignment editor decide which reporter covers a particular story.

Line producers also work with each other to ensure that their newscasts are not repetitious. Because viewers expect updated news throughout the day, line producers coordinate their efforts among the 5pm, 6pm, and 11pm newscasts. For example, the 5pm producer may inform the 6pm producer that the 5pm program will lead with a package on traffic fatalities. The 6pm producer won’t want to duplicate that lead, even if it is a hard-hitting story. Instead, that second newscast may have the reporter begin the newscast with a live shot in the field, followed by a voiceover (which was cut from the 5pm package’s footage). This allows the news to be updated for each program, offering viewers something new to watch on the next show.

Associate Producer

In large cities and network newsrooms, the line producer has assistants to help carry the load. These associate producers help reporters put together packages when they are in a rush or have been assigned to a second story. They cut sound bites and pick video for the packages. When a package is reduced to a voiceover, the associate producer usually handles all the details, including writing the script. They also produce VOSOTs.

The associate producer typically coordinates the microwave and satellite feeds from reporters in the field. Working closely with the line producer, the associate producer informs him or her if the feed has any problems. The associate producer often selects and edits parts of the feed to be used as voiceovers. Again, depending on the size of the news operation, there may not be any associate producers—writers are assigned the same duties. In many smaller markets, reporters are responsible for editing the package together with little or no help.

Field Producer

Usually found in larger markets and at networks, field producers help reporters with research and detail work, setting up interviews, locating people at the scene of the story (often in advance), directing the videographer, and making travel arrangements. The field producer is often described as the “advance” person or “facilitator.” He or she speaks with the newsmakers in advance of the reporter’s arrival, briefs the reporter on what the interviewees know about the story, and suggests questions to ask in interviews.

Web Producer

One benefit of the 24-hour news cycle is the ability for newsrooms to have an online presence so viewers can find Internet updates at their leisure. This has led to the birth of web producers, who constantly update their stations’ websites. Maggie McGlamry, web producer for WGXA in Macon, says:

As a web producer, my job relies heavily on social media. Once I publish the news stories on our station’s website, I share the stories on Facebook and Twitter to get a wider viewership. An important part of my job is to know which stories will do well on social media, and even further than that, which social media outlets to use. For example, “feel-good” stories are a great way to increase viewership because no matter where in the country or world the story occurs, people online gravitate toward spreading happier news. Additionally, if hard news (like a murder) occurs locally, people in our DMA spread the stories via social media because it’s close to home.

FIGURE 14.2 Kuzma/iStockphoto.com

The skills needed for web producing are akin to those found among show producers, but there is a distinct difference in speed. Unlike viewers that watch the newscast at 6pm or 11pm, social media users expect information around the clock. McGlamry continues:

Being quick is the second most important part of my job, behind accuracy. In my DMA there are two other news stations, so we are always trying to publish news first. We are constantly checking social media accounts and looking for leads to new stories. Once we have a new story, my job is to type it up and get it on the web as quickly as possible. There is always a feeling of satisfaction when I get a story out to our viewers before the other stations. Of course, publishing first doesn’t matter if it isn’t accurate information. We lose credibility every time an inaccuracy is pub lished, so we always take the time to ask for clarifica tions or sources when needed.

FIGURE 14.3

It’s a good idea to avoid leaving viewers with a sense that “there’s nothing good in the news tonight” by working some “uplifting” stories into the show.

Producers and Writing Skills

In addition to having solid time management aptitude, the ability to deal with multiple ongoing tasks and personalities, and possessing the news judgment to make sure the best possible stories get on the air, each producer must have ex ceptional writing skills. This goes beyond simply writing bumps and transitions to string together stories to create a newscast. This means being able to rewrite national readers on the fly, help reporters hone a 45-second story into a 30-second news hole, and craft a quick lead for a story when everyone else in the newsroom is drawing a blank.

As noted in the earlier chapters on writing, the elements of putting together a story still rely on the traditional concepts of getting the information correct, starting with the most vital facts in a compelling lead, relaying everything in a conversational but authoritative style, and focusing on telling a story that engages the viewer. Underpinning all of this is good writing. The duty of every producer is not just to create a strong newscast, but to use the right words to tell the best news stories possible. Even though they are not seen on air as anchors and reporters, the producers still willingly provide the voice of the newscast every day.

THE LOGISTICS AND STRATEGIES OF PRODUCING

Like some other elements of news (anchoring, reporting, and editing), producing is best learned via real-life experiences. Through experience, newscast producers learn that they face the same challenges regardless of the size of their viewing audience, the number of reporters they lead, or whether their newscast is a five-minute update at 7:25am or an evening report at 11pm. There is rarely enough time or manpower to make all of the stories fit, yet producers pull it off every day.

There are basic steps that are universal in newsrooms. The newscasts begin with staff meetings, continue throughout the day as stories either thrive or die, and then finally go on air at their appointed hour. While no two days are ever alike, there are steps that make the producing job much more manageable.

Staff Meetings

The producers hold staff meetings as many as three times a day—in the morning, the late afternoon, and after the early evening newscast—to discuss that day’s news coverage. That’s where initial newscast decisions are made: What will the lead story be? Which stories will be covered? Which reporter and videographer will cover them? Keep in mind that these decisions are subject to change, depending on the day’s events. The last meeting of the day is a debriefing to discuss what went right and wrong with the early evening newscasts and to plan coverage for the late evening news.

The meeting is a place to discuss story ideas; it’s not unlike a war room where the battle plan is set for that day’s action. All staff members are expected to contribute and share information. A good producer is a good listener who realizes that ideas are not limited to the assignment editor. KFVS12’s Robbyn DeSpain notes:

There are several factors that determine how much time is devoted to a story in my newscast. What is its impact or benefit to the viewer? What kind of visual elements do I have to support it such as an interview, video, or graphics? How much explaining does it need to make sense? Those questions are answered at the morning and afternoon editorial meetings. When a reporter pitches a story, a conversation is had about what the focus of that story should be and how it can be best be told. When a story doesn’t have a lot of supportive video, then graphics or a series of informative standups can be used to make it more appealing. I determine the best way to tell each story, and often use a map or a graphic as a better way than just locator video.

During the meeting, the staff goes over each story available for the day’s newscasts. Decisions are made, and the line (show) producers of the early evening newscasts create a rundown (lineup), which is a list of stories planned for those newscasts. Reporters and camera people are then assigned to stories.

The Rundown

The preliminary rundown is what comes out of the staff meetings. Decisions reached at the morning meeting determine what goes into the rundown for the evening news, and discussions at the afternoon meeting establish what the late-night news looks like. But all this is subject to change depending on breaking news stories, because the rundown is a living document. At times, the rundown looks exactly like the newscast, whereas at other times it looks nothing like it because of unpredictable developments. Atlanta’s WSB-TV Director Lucas Johnson says stories are constantly added or dropped from newscasts. Johnson says:

There are producers who will not leave a single block of the show alone. They’ll float one story and then have to change every other anchor read in the block as a result. We use the Grass Valley Ignite control room automation system and when a change is made, it takes three to seven seconds to import the change. During that time, we can’t do anything, so we have to make sure we have the time to take the import. We typically try to import during a PKG or long VO.

FIGURE 14.4 track5/iStockphoto.com

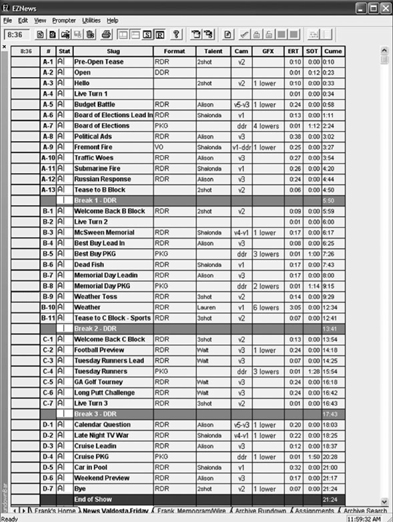

A rundown is a blueprint of what stories will be presented in a newscast, which anchor reads them, how long the story lasts, and what type of story it is (such as a reader or package). This sample rundown is identical to the one you’ve already seen in Chapter 2. To quickly review, the column headings across the top are as follows:

■Number, or #—where a story appears in the newscast.

■Stat—short for “status,” it shows if the story is approved for air.

■Slug—a two- or three-word description or title of the story.

■Format—whether a story is simply read by the anchor, has video, or is a field package from a reporter.

■Talent—which anchor(s) is on camera.

■Cam—which camera or video source should be on air.

■Gphx—tells the director what graphics are needed, if any.

■ERT—estimated run time, used by producers to predict how much time a story will take in the newscast.

■SOT—sound on tape, it shows how long preproduced segments, such as commercial breaks and packages, will take in the newscast.

■Cume—the cumulative time of all stories thus far in the rundown.

As you scan the rundown, you’ll notice that the A block stories are mostly local except for two international stories in a “global wrap” that ends the segment. B block has four stories (two of which are packages), followed by weather. Sports is the C block while D block has lighter feature packages to close out the show. Alison and Shalonda are the news anchors, Lauren covers weather, and Walt is the sportscaster.

A lot of thought must go into the arrangement of stories in the newscast to make it clear and interesting. As mentioned earlier, no two producers are likely to agree on the exact order of the stories in a newscast. If you examined the newscasts produced at stations in the same market on the same night, even the lead stories are often different unless some story completely dominates the news. Naturally, rundowns are frequently changed at the last moment as new stories come in, current stories are updated, and weak stories are dropped.

Name—Robbyn DeSpain

Job Title—Assistant News Director

Employer and Website—KFVS12, Cape Girardeau, MO; kfvs12.com

Social Media Outlets I Use—Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter

Typical Daily Duties—As Assistant News Director, I start my day by watching as much of the morning newscast as I can. That way I know what’s happened overnight, and I can go ahead and start thinking about coverage that day.

The morning editorial meeting is my first priority when I arrive at work. That is where the dayside reporters pitch their stories, we assign them, and talk about other coverage for the 4, 5, and 6pm newscasts. After that, I do all sorts of other things including attending management meetings, scheduling, approving timecards, taking part in producer and reporter reviews, and other things assigned by the news director.

As we get closer to newscast time, I work with the producers on showcasing their content, the reporters on fleshing out their stories, and the web team on getting stories posted online, on the station app, and sent out on social media. I also help guide breaking news coverage and planning. During the shows, I’ll watch them with the news director and help with writing or questions as needed.

Assembling a newscast so that it flows naturally from story to story, engages the viewer, and includes all of the day’s news is no easy feat; a sample exercise at the end of this chapter illustrates the juggling act faced by producers every day. There are, fortunately, some basic strategies that assist in fleshing out the rundown.

FIGURE 14.5 Courtesy of EZ News

Leads, Clusters, and Kickers

As in the above rundown, let’s assume there are four blocks in a local newscast. The blocks are separated by commercial breaks; thus the newscast flows as A block, break, B block, break, C block (usually sports), break, and then D block. Most producers aren’t terribly concerned with the content of C block, as the sports anchor will manage that for them.

Of course, the producer is interested in the total running time of C block so it will fit cleanly with the rest of the newscast. Also, if there is a “news” story hidden in sports, that may be of interest. A referendum on building a new football stadium may be placed in C block, although the news angle may warrant that report being moved to A block. Typically, a four-block newscast is split into the following:

■A block—a quick bump followed by the anchor introductions, then the block is filled with “hard news.” It closes with a tease to B block.

■B block—this block is filled with “lighter news,” such as education and health updates. Weather is often in the bottom of this block. It closes with a tease to sports in C block.

■C block—the sports segment thrives here. This block may open and close with banter among the news and sports anchors.

■D block—features, entertainment stories, and feel-good news are used to close out the show.

By leaving C block to sports, we’re left with A, B, and D for news. The first block, A, begins with the lead story of the newscast. The format of this news story may be a package, a live shot, or even a reader. Yet the mere placement of it above all others means it is the lead story, thus it is more important to the viewers than anything that follows.

After the lead is decided, many producers cluster their stories into the remaining slots. All health stories may be bundled in B block, while three short statewide readers at the bottom of A block may constitute a “state round-up.” The life or death of stories is decided at this stage, as a precious 20 seconds spent on a traffic jam may erase the 20 seconds needed for a school board update. Also, the weather report may be attached to the end of B block, so the producer must be very careful about what story to insert before the forecast. A story on a farmer’s crop would be a logical tie-in to the weather segment, but tragic numbers on an increase in child abuse would not.

Unlike A and B blocks, D block does not have the same hard news implication. Instead, D block is home to entertainment news, feel-good pieces on cute kids, and community announcements of upcoming festivals. D block is designed as a kicker block for two simple reasons. First, if the newscast is running over time, it is easy to drop the feature stories from D block without losing the newscast’s impact. Second, no anchor wants to end the newscast on a depressing story, only to then abruptly shift gears by saying, “Good night, stay tuned for Wheel of Fortune!”

FIGURE 14.6 naphtalina/iStockphoto.com

Peaks and Valleys

One popular approach to producing a newscast is known as the peak-and-valley format. Although the phrase has been around for decades, many producers use the format without using that name. This format treats every segment, or block, in the newscast as a sort of mini-newscast that can stand on its own. That doesn’t mean that each section has weather, sports, and financial news, but there is a good, strong story at the top of each segment, along with some less important stories and, in some segments, perhaps a feature or special report. Each segment ends with a strong story before the commercial.

The concept behind peaks and valleys is that if you sprinkle your most interesting and important stories throughout the newscast, you’ll hold your audience. If you place all your top stories in the early part of the newscast, you’ll lose the audience because the newscast—and your audience—will fizz out by the middle. Worse yet, the audience will switch to your competition. Instead, you should spread your most interesting and important stories throughout the newscast.

It’s also crucial to remember that weather is the most promotable element in a newscast. Many viewers say that weather is the main reason they watch local news, which is why producers tease it throughout the newscast.

For producers who use the “peak-and-valley” theory, it is extremely important before going to a commercial break to tease not only the weather, but also a strong story that has special appeal. The idea is that if you do not hook listeners on the first tease, you may get them on the second. If you do, it will keep the audience around through the commercial, which is another valley of the newscast. After the commercial, the audience expects another good story at the top of the next segment and the process begins all over again: A peak and then a valley and another peak and another valley, throughout each section of the show.

This theory of producing is different from the traditional approach (which started in radio), which gives the audience the best stories at the top of the newscast and follows them with stories of less and less interest until it’s time to say goodbye. This format made sense for radio and for early TV newscasts, which lasted a mere 15 minutes, including commercials.

The inverted pyramid approach continues in many small markets because it often is difficult even to find just one strong story each night. Too many producers still try to hold an audience by teasing sports and weather. In many communities, of course, sports and the weather are important news, as are college and high school sports scores. In farming communities, the weather may be the best story of the day, night, and week. But creative producers, even in small markets, should experiment with the peak-and-valley theory that teases other important stories or good features.

Rhythm and Flow

Although packages appeal most to the audience, producers shouldn’t play one off another. You should place them effectively throughout the news-cast, inserting readers or voiceovers between them. The package also serves another important purpose; it gives the anchors a breather and a chance for them, the producers, and the director to get organized for the rest of the show.

The line producer, who sits near the director in the control room, often needs time to reshuffle parts of the rundown and script because of late-breaking news and because packages are often still being edited during the newscast. Problems also develop when hard drives or computers crash as minutes tick away. The old scenario of tapes being “eaten” by VCRs has been replaced by the new problem of computers freezing during the final edits of a story. Although the technology has evolved, the glitches that can occur under deadline pressure have not.

FIGURE 14.7 Freder/iStockphoto.com

Ad-Libs, Bumps, Teases, and Tosses

In the 1980s, the “happy talk” phenomenon invaded a number of local television stations. This occurred when banter among the anchors became less about the news and more about themselves. Although it was an attempt to humanize the news anchors and make them more accessible to viewers, the fad seemed forced onto the news sets.

Today, most banter is limited to ad-libs, bumps, teases, and tosses. These terms may be used interchangeably in newsrooms, although there are some slight differences.

Ad-libs are used when the newscast runs short by perhaps 20 seconds. Instead of cramming in a final reader, the producer will alert the news team to ad-lib. The typical solution is to bring the weatherman back into action one last time to casually talk about the weather and joke with the anchors about whether they will need a jacket that evening. Sometimes, this is by design so late viewers can quickly glimpse the weather forecast. Other times, it’s because the producer had a story fall through. Either way, since the weatherman works without a teleprompter and is an expert at extemporaneous speaking, bringing them back on set is the perfect way to save a producer’s final segment.

Bumps and teases are similar to one another, but there is a subtle difference. Say the anchors are ending the A block and heading to a commercial break. A bump is generic, such as, “We’ll be back with more. Stay with us.” These are handy if the anchor doesn’t know what’s coming in the next block or, as is sometimes the case, the producer isn’t sure if a late-breaking story or last-minute live shot will come through. In these cases, bumps are perfectly appropriate.

Teases are far stronger. They promote a story in the next block, give a peek at the weather forecast, or maybe tease viewers into staying for something much later in the program. Here are examples of possible teases at the end of an A block:

You may think it’s just cold weather around the corner, but Heidi has a bone-chilling prediction when we return with her weather forecast.

If you thought traffic was bad today, wait until you hear what streets will be closed for construction starting tomorrow. We’ll have the details in a moment.

Looking ahead to sports, a blockbuster basketball trade has made one local player very happy, but his teammates are crying foul.

Any of the above is better than the typical “Stay with us.” A well-crafted tease is essential for keeping the audience over the commercial break. They are often the last tidbits inserted into the script (the rundown must be done first so the producer knows what story to tease), but are vital in holding the newscast together.

A toss is simple. This occurs when the sports or weather anchor is introduced to give their segment. These are unscripted; the teleprompter just reads TOSS TO SPORTS. The anchor finishes the news copy, sees the TOSS order on the teleprompter, pivots to the sports anchor, and quickly tosses the reins over. During the commercial break, the sports and weather anchors give the news anchors an idea of what would make a good toss. Although it’s similar to an ad-lib, a toss is an internal transition among the anchors. An ad-lib is more likely used to just fill time.

KYTV Anchor Ethan Forhetz stresses that time management is key to keeping the newscast flowing properly. To do this, he says there needs to be good communication from the producer in the control room to the anchors on set, adding:

Our producers will typically build in a little “chat time” after a story that is a talker or a viral video that we air. The time cues grow in importance as we get toward the end of the newscast. Seconds are increasingly valuable in the latter blocks of the show. It’s up to the producer to tell the anchors whether we have any time to fill. These days, weather rules the world, so if we get toward the end of the broadcast, it’s better to bring back the meteorologist in the last block than to chat with sports because, as a rule, more people are interested in the weather that might affect them than anything sports related.

An acknowledgment should also be made for local weather and sports anchors everywhere. Both deliver segments of several minutes per newscast, but each is aware that their respective time allotments can expand or contract dramatically depending on the news of the day. On a busy news day, sports and weather may each lose 30 or 45 seconds to accommodate an onslaught of news stories. On a slow day, the producer may ask them who would like more time to fill. This is when you’ll see the weather anchor spend more time discussing the pollen count or the sports anchor may insert a “Play of the Day” segment that usually isn’t aired.

Finally, both weather and sports anchors are expected to be on the set at the end of the newscast. If an ad-lib is needed, that quick weather update or a reminder about a local sports event is always good for 20 seconds.

TECHNICAL ASPECTS OF PRODUCING

In addition to getting the holistic pacing and scripting of the newscast correct, the producer must supervise the many technical aspects of putting the show together. Some of the considerations that should be addressed are the use of the graphics and downstream keys, balancing the anchors, the use of still pictures, how to properly incorporate live shots, and how to make sure the timing is correct for the entire newscast. We’ll first examine how graphics and digital elements can help the newscast.

DSKs and Graphics

The addition of digital graphics on newscasts serves different purposes. Not only does it improve the overall “look” of the program, graphics can convey information to the viewer that the anchor doesn’t need to read aloud.

The most basic graphic is the DSK. This stands for downstream key and is frequently referred to as a key. These are generally two lines long and appear in the lower portion of the image. When an anchor is on camera, the top line has the anchor’s name while the second line identifies the name of the program, like “News 13” or “Action News 5.” These keys are also used to identify interview subjects, reporters, and anyone else who appears on camera.

Other visual images that can help convey a story include box graphics and side graphics. The box graphic is familiar; as the anchor speaks, a box hangs over their shoulder with a quick visual reference about the story. For example, a story about El Salvador will use a box graphic of either the country’s flag or a locator map of the country itself.

A graphic that is more expansive and gives much more information is a side graphic, also called a split screen or split-screen overlay. This graphic is perfect if the producer wants to convey a short list, such as what voting locations are open or tips on how to winterize your house.

Still Pictures

Producers can use still pictures if video is not available. Think of a voiceover with a producer reading the copy over a series of still images. It is not as dramatic as video, but in some instances, still shots may be the only available option. For example, if there is a story about a famous singer, copyright laws could prohibit the newscast showing footage from a concert. However, the use of still pictures in a voiceover format is a perfectly acceptable alternative that can sidestep those copyright restrictions.

Maps and other graphics also should be used to support copy. If a plane has crashed in some relatively unknown area, it helps the viewer if you show a locator map and indicate with a star where the plane went down. The map should include at least one town familiar to your audience. Creating the images is easy if the station employs a dedicated graphics artist; simply email over the work request and it can usually be finished before the newscast. Another popular option is downloading still images from the national newsfeed. The most popular feeds, such as CNN’s Newsource, offer still images and maps for download. Other services are seen frequently on the air, especially for national and international maps. Google Earth is one example of a map service that can quickly illustrate locations for the viewers.

Balancing the Anchors

Visualize two anchors relaying the news on an evening newscast. Except for the weather and sports anchors, the two news anchors are the foundation of the program; the viewers expect to see them five evenings a week. The station’s management hires anchors to lend credibility, convey authority, and serve as the “face” for the station’s local presence. The anchors are promoted on billboards and in newspapers and are frequently approached in public on a first-name basis.

Producers are aware of both the station’s financial investment in the anchors and the viewers’ emotional investment in them. To make sure the anchors appear on camera and share enough time on air (often snidely called face time), the line producer should double-check the rundown for anchor balance. If one anchor will present seven readers and the other has only two, then the first anchor will appear on camera much longer than the other. This may happen in an occasional program, but if one anchor is consistently shown on camera while the other is hidden behind voiceovers, the news director is bound to notice. Even worse, the anchor with less face time will object. When the line producer is confronted with a series of rundowns that reveal a perceived slant for one anchor over another, the meeting will quickly become unpleasant.

As a side note, newsrooms are filled with anchors who feel they always receive the stories with difficult-to-pronounce foreign names or tongue-twisting medical phrases. Most veteran anchors realize that a pure balance (of either tricky stories or stacks of readers) is difficult to achieve every night. However, the line producer must be fair in balancing the anchors over the course of newscasts.

FIGURE 14.8 Stock image/Shutterstock.com

Live Shots

Ever since technology allowed TV stations to go live from the scene on a daily basis, there has been a debate about whether the technique is being overused. If there is a major traffic snarl in New York City because of road construction during the rush hour, does it make any sense to send a reporter back to the scene for the 11pm news—as one station did—when the highway is virtually abandoned? Even the reporter at the scene was annoyed by this decision because it was cold and she was shivering. “What the hell am I doing here?” she asked on the two-way radio, before the anchor tossed the broadcast to her.

The need to use the live shot as much as possible seems to have diminished somewhat as the novelty wore off and station managers have complained less to news directors. In the past, the managers often said, “We paid a bunch for this stuff . . . make it pay for itself.”

Most news managers also say the public tends to believe that a reporter at the scene is more on top of a story than a reporter getting his or her information over the phone. Finally, they say, newsmakers are more likely to talk to a reporter in person than on the phone. “It’s easy to say no to a strange voice on the phone,” said a producer, “but it’s difficult to say no to a reporter while looking him in the eye.”

There is no clear rule of thumb that dictates when a live shot is warranted. Even for veteran producers, it is a highly subjective call. A breaking story about a verdict from a courthouse? Sure. A forest fire that is sweeping toward the city limits? Absolutely. A live shot for the noon show foretelling the weekly opening of a local art display scheduled for 9 o’clock that night? Not so much.

Back Timing

One major task for the line producer is to ensure that the newscast gets off the air on time. This is particularly important when computers are in charge of establishing when programs and commercials start and end. We have all witnessed situations when one program is cut off abruptly by a new program. That situation happens because a computer has established the time when the new program or commercial is supposed to start.

The timing is particularly critical when local news is followed by a network program. The network computer will take over regardless. If the local news anchors are still saying goodbye or the station’s final commercial or logo is still playing, something is going to get cut off if the newscast timing is not accurate. If your commercial is cut, that revenue goes down the drain.

To defend against such problems, the show producer must track whether the newscast is “running on time.” Anchors may stumble on some lines, a package may be mistimed, or the banter between the on-set talent may be too short or long. That’s why producing is so difficult; the unexpected often happens. If the newscast is short, something else must be added to fill the time. The opposite is true if the show is running long—something must be cut. As a result, producers use back timing to make sure the program ends on time. In most newsrooms, the computer system back times a show for you, but a producer must be able to do the math on his or her own.

The computer tells you automatic ally where you stand on time at each point in the newscast. A “minus” sign means the show is running long. Figuring the time works like this: Take the total amount of time for the show, which is typically 30 minutes. Sub tract time for commer cials, which the station is contrac tually obli gated to run during the program. The amount of time left is the news hole, which is the time allocated for news to fill up the rest of the show until it reaches 30 minutes. In most cases, commercials take up eight minutes, leaving 22 minutes for news. But once weather, sports, the prerecorded open, the show’s goodbye, and the various teases are included, the amount of time for actual news drops to between 12 and 15 minutes.

FIGURE 14.9

The bottom line is that you must finish the newscast on time. This helps explain why readers may be shaved from 30 seconds down to 20, or why packages are trimmed down to VOs. News waits for no one, especially a producer who mistimes a show.

SUMMARY

The best opportunities for young people entering broadcast news are in producing. The expansion of local news and the spread of all-news channels to more cities have created a need for producers of all kinds. There is a high demand for producers because so many young people want to go on the air because of the perceived “glamour” and higher salaries usually associated with such jobs. The competition for anchor and reporter positions is much greater, even though producer positions may be available.

There also are substantial rewards in producing news programs. Certainly, salaries are going to continue to improve as the demand increases for people to produce news. Although producers work behind the scenes, their jobs are exciting and occasionally also glamorous. The excitement comes in the realization that as a producer you are “in control.” What you do in the newsroom determines what goes on the air. You are limited only by your own imagination and creativity. As pointed out earlier, in many newsrooms, the producers are in complete charge of the news.

Along with that power comes a lot of responsibility and risk. You will need good news judgment and other skills in many areas. Good writing is essential. Some experience in reporting is also desirable. You will also need to have an excellent knowledge of production techniques—microwave and satellite feeds, computer technologies, video editing, electronic still storage, and emerging technologies.

Another important consideration is stress. It’s a tough, emotionally and physically draining position with long hours. But the potential rewards are great if you have any interest in management. Producers are on the best track to the management offices. You must learn how to do just about everything in the newsroom and how to work with and manage a variety of co-workers. Who could be better qualified for the boss’s job?

Test Your Knowledge

1.List the various duties of the executive producer.

2.What are the responsibilities of the line producer?

3.Describe what the field producer does.

4.What is a rundown and why is it so important?

5.Explain the “peak-and-valley” theory of producing.

6.What is the meaning of the term inverted pyramid in producing?

7.What is a live shot and when should it be used?

8.What’s the purpose of the staff meetings?

9.Explain the term back time. Why is it so important?

10.Why is it important for a news station to have a web producer?

EXERCISES

1.Try to arrange with one of your local TV stations to “hang out” with a producer. Weekends are the best time because the pace is usually slower.

2.Arrange to accompany a field producer on a photo shoot. If there is none in your market, go along with the reporter who, in this case, is the field producer.

3.Take notes as you watch a local newscast and try to determine what kind of a format the producer is using. See if you can spot “peaks and valleys.”

4.Watch a local evening newscast. Then, check the station’s website to see if all of the stories are online, paying close attention to which stories have been updated on the Internet.

IN-CLASS EXERCISE: CREATING A NEWSCAST

As stated earlier, no two producers are likely to decide the exact same order of the stories in a newscast. If you examine the newscasts at different stations in the same market on the same night, you’d see that even the lead stories are often different unless some story completely dominates the news.

For this exercise, assume you are the producer of the 6pm news on a weekday in mid-August. At your 9am production meeting, you learn of the following stories. Which would you pursue for your A block, B block, and D block? Remember, weather is at the end of B block and sports occupies C block. Also, you will not use all of the stories:

1.From your health reporter: A 1:15 PKG on obesity, the fourth in a five-part series on modern health hazards.

2.From your futures files: The city council will meet at 7pm to discuss school rezoning. You have archival footage and can preview this meeting with a RDR, VO, VOSOT, PKG, or live shot from the location.

3.From the newswire: A Census Bureau report shows your county has gained a 9% minority population over the past year—this exceeds the state’s 4% gain.

4.From the newswire: Housing stats are down nationwide. Your state and city mirror the national trend.

5.From one of your videographers: Video footage of an early morning house fire in town. The structure was destroyed, but no one was hurt or killed.

6.From Twitter: A local Boy Scout troop has built a scale-model home out of toothpicks, which is on display at the mall. The display is to promote awareness of using renewable resources for shelter.

7.From your futures file: The airport authority is meeting at 3pm to discuss a possible runway extension. You can dispatch a crew to cover it or use file footage.

8.From Facebook: A local group of approximately 20 activists is alerting all news media of its protest at tonight’s city council meeting. They want a local park to be renamed in honor of a local civil rights leader.

9.From the newswire: The summer heat wave shows no signs of abating. High temperatures and humidity are forecast for at least the next week. So far, eleven people have died in your state due to heat stress over the past six weeks.

10.From one of your reporters: School will resume next week. A 1:05 PKG on back-to-school preparations is available.

11.From one of your reporters: The local university also begins classes next week. The university reports that student enrollment is down almost 6%.

12.From your futures file: The county extension agent will host an open house this weekend to aid farmers with seasonal crops.

13.From the overnight beat checks: An elderly couple was mugged last night while walking near their home. Both of the victims suffered minor injuries. The husband told police he wants revenge and isn’t afraid to use his gun.

14.From the newswire: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued a heat stress advisory for your area due to the ongoing heat wave.

15.From the fax machine: The city public information officer has sent an advisory that residents should restrict watering their lawns to evenings or early morning hours.