Chapter 1

The Need for Building Better Businesses

The book's Introduction provided information on how the LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® method was developed to specifically address challenges that LEGO faced. Though many things have changed since the turn of 2001/2002, challenges like these have only become even clearer and more urgent. Our experience has brought to light a number of issues in how business and management is conducted that have led to a continued demand or need for LEGO SERIOUS PLAY, and the difference it can make.

Three areas where LEGO SERIOUS PLAY provides a solution are:

- Beyond 20/80 meetings and Creating leaning in

- Leading to unlock

- Breaking habitual thinking

We present this sequence (as shown in Figure 1.1) in this particular order for a reason: first the manager has to break the 20/80 dynamics and create meetings where everybody is leaning in and contributing. Once this happens, he or she needs to lead to unlock everyone's full potential and, finally, do so in a way that breaks the habitual thinking and unearths new and surprising insights.

Figure 1.1 How the Method Creates Value

Our description of the types of challenges focuses less on the content and more on dynamics or structure. This aligns with our view of LEGO SERIOUS PLAY as a language. The manager may want to go beyond 20/80, lead to unlock, or break habitual thinking on almost any complex issue.

So, let's go into a bit more depth on the three types of challenges.

Beyond 20/80 and Creating Leaning In

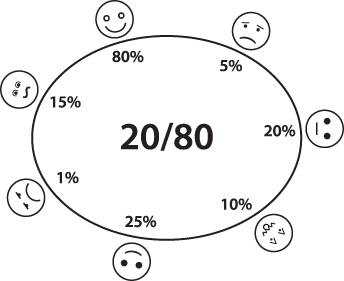

The drawing in Figure 1.2 captures the flow, or lack of flow, of most meetings in many organizations.

Figure 1.2 Typical 20/80 Meeting

One or two individuals, often the most senior member and/or the meeting's host, control and enjoy the meeting. These 20 percent of the participants take 80 percent of the time, hence the title of 20/80. To make matters worse, these individuals typically contribute only 70 to 80 percent of their full potential in order to solve the meeting's issues. The remaining 80 percent of the participants contribute far less, arguably down to a few percent of their potential. In addition, they have a negative experience—a feeling that they may even carry into work after the meeting.

The main reason for this is that a couple of such dominant, extroverted or quick-thinking people around the table immediately start talking, prompting them to take over the agenda and the angle from which the content is discussed. There is no democratic process ensuring that everybody both has a voice and is obliged to use it.

These meetings very often have an additional characteristic: the participants are physically leaning out rather than leaning into the conversation. They push away from the table, slide down into their chairs, glance out the window, or check e-mails or status on social media on their smartphones. Their bodily actions mirror their state of mind, and highlight their rather unengaged position.

Both 20/80 and leaning out are dynamics that lead to lower-quality in-person meetings. The so-called attention density is low. We will refer to attention density further in Chapter 7; however, the key definition of it is that it is the combination of how long we pay attention to something and how much we pay attention to it. The how much can further be divided into are we listening, or are we listening and looking, or are we even listening, looking, and touching. Meeting attendees are creating very little or even no new knowledge, and thus no new solutions. These meetings may even destroy value—partly because the participants are taken away from value-creating activities, partly because employees haven't solved the complex issue the meeting was intended to address, and partly because the meeting itself destroys collaborative efforts between the individuals and may even create stress (which has a very negative impact on the brain).

Managers and leaders need to create 100/100 meetings, conversations where 100 percent of attendees are contributing their full potential—100 percent of what they have to offer.

Leading in Order to Unlock

Once the manager has succeeded in creating 100/100 meetings where all participants contribute, a new leadership challenge emerges: leading to unlock.

Specifically, managers must unlock potential in three areas: the knowledge in the room, people's understanding of the system, and the connection between the individual's and the organization's purpose. Let's look at each of these.

The Knowledge in the Room

Knowledge is the first area where the manager's role will change. We all have access to more data and information nowadays than any one person can handle, or even has the remotest chance of remembering. Very often, we aren't even aware of or certain about our own knowledge on a given topic. Therefore, when you have a number of very smart people suddenly eager to contribute but who don't necessarily know exactly how they can form a solution, it becomes the leader/manager's job to unlock each individual's knowledge and uncover patterns in what each is sharing.

We have just indicated an interesting angle that makes this challenge even more daunting: people themselves often don't even know what they know. This has to do with the intricacies of our brains; part of what we know is stored deeply in the brain but other elements are stored in different places in the cortex or even the hippocampus. And since we don't always know exactly how much we know, we're frequently not even aware that we know something.

Chapter 7 will go into more detail on memory. For now, the message is this: in order to innovate and transform businesses and activities, everyone needs to activate more of their knowledge and find underlying and often surprising patterns. Additionally, if we want to intentionally transform an activity—individually or as team—we need to make this clear and shared. And leading to unlock requires us to make this possible.

Understanding the System

The manager's second task is to help unlock the understanding or properties of the system. This includes creating a culture and process where there is an understanding that the organization needs to probe, sense, and then respond—and doing so in a sustainable manner. This need has become more urgent recently, since most of today's organizations compete or collaborate in complex adaptive systems. Unlocking this understanding is crucial, because complex adaptive systems have emergent properties. When a system has emergent properties, it means that we cannot predict or outline how a single alteration may change the entire system. Such alterations, often called emergence, are defined by being dynamic, unforeseen, and changing the state of the system.

The leadership challenge has moved from succeeding in the simple systems of years gone by, and in most cases also beyond succeeding in complicated systems. In simple systems, it was possible to make sense of information, categorize, and respond accordingly. Best practices worked, and bureaucracies excelled in such systems.

Though this is a bit more challenging in complicated systems, they still offer the opportunity to make sense of information. Individuals can then analyze and respond based on this understanding. Experts fare well in complicated systems; one could ponder whether the “manager as an expert” paradigm is a natural response to competing in a complicated system.

However, a complex system takes on emergent properties. Consequently, managers and employees cannot collect the information in an inactive manner. Rather, they have to probe the system, learn from this, and then respond. There is more mutual influence here; agents coevolve the system, which is why understanding has to be unlocked.

This process includes developing an understanding of the group's current identity, what it can be in the future, and how this would change the system. We can perceive the identity as a strange attractor in the complex adaptive system. It also requires that members of a group get a grasp on what they can change versus what they cannot, and in which combinations. Finally, all of this must be monitored.

Connecting Purposes between Organization and Individual

Finally, the manager is left with the unlocking the connection between the purpose of the company and the employees. This element in some part builds directly on what happens when the group is able to unlock an understanding of the system. As written earlier, this is based on the ability to understand the group's identity, which inevitably leads to a clarification of its purpose.

When a manager is able to create a connection between the organization's and the employees' purposes, then engagement typically grows; the organization fares better, and the employees are more satisfied. Connecting purposes creates similar pursuits and more meaningful relationships between all parties involved, and benefits everyone—including the customer.

Many make the argument that members of the workforce are increasingly fickle or substantially more loyal to their personal life vision rather than that of the company. Hence, if a company can connect its own goals with its employees' goals, the organization becomes more resilient and more agile at a time when those capabilities are needed most.

Breaking Habitual Thinking

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, employees have access to a lot of data, and often have a very deep understanding of their expertise. While this occasionally leads to the challenge of unlocking all of this knowledge, it also brings to light another challenge: breaking habitual thinking.

We humans tend to look for the first pattern that fits what we know, and then stay with it. A strong subject matter expertise often leads us to feel that we know what to look for, and hence will look only for that. We will find data that support us and, unfortunately, unconsciously ignore disturbing information. This causes us to miss surprising and valuable patterns.

We see a classic example of this in Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons's The Invisible Gorilla test, where they studied the concept of selective attention.1 In this experiment, the observer sees two teams of young people standing in a circle and passing two basketballs between them. The observer is then challenged to count how often one of the teams passes the ball. Midway through the video an adult dressed up like a gorilla goes into the middle of the circle, punches its chest, and seemingly roars. Very few people see the gorilla, for the simple reason that they are focused on counting passes. It is very likely that such selective focus was part of the downfall of Kodak, as it kept ignoring digital photography, or Blockbuster missing out on streaming, unlike its then competitor Netflix. However, this is not a recent phenomenon; in 1878 Sir William Preece, chief engineer at the British Post Office, said:

The Americans have need of the telephone, but we do not. We have plenty of messenger boys.

Clearly the wrong data to focus on.

Therefore, the manager's final challenge is to help the team members to break their habitual patterns of thinking. He or she needs to help everyone suspend going for the first acceptable solution, and instead think once more, think differently, and then see the new pattern that leads to a surprising solution. Here is an example of how this worked out for the manager and founder of Scurri, an Internet start-up based on the coast of Ireland.

Contemplating the Needs

The red thread through all the needs that we have listed here is that the manager wants—truly, needs—to build a better and more sustainable business. However, he or she must do it by unlocking something so far unknown. These unknowns are knowledge both within each person's head and between people's brains, knowledge of the system, the connection between purposes, and finding the surprise by breaking habitual thinking.

Once the manager uses the LEGO SERIOUS PLAY method to unlock these unknowns, he or she can create a deep impact where the transformation happens on two levels:

- Individually, for the employees involved in the workshop, it changes something in their understanding and thus their personal commitment to change.

- Organizationally, it changes how the organization works. This could, for example, be in the direction (vision) or in how decisions are made between people (culture).

Are these challenges new? Are they unique to the time we live in? Maybe not, as always, change has never happened faster than “right now.” The following is a classic quote attributed to Scientific American in 1867:

It is not too much to say…that more has been done, richer and more prolific discoveries have been made, grander achievements have been realized in the course of the 50 years of our own lifetime than in all the previous lifetime of the race. It is in the three momentous matters of light, locomotion, and communication that the progress effected in this generation contrasts surprisingly with the aggregate of the progress effected in all the generations put together since the earliest dawn of authentic history.

If nothing else, it is a good reminder that everyone has always lived in times of great change, and it has never happened faster than whenever “right now” may be. Consequently, managers have always been met with increasingly difficult problems, shorter development time, higher pace of change, and so on.

It's important to consider what characterizes the system and the time in which these complex problems arise. We see the need for LEGO SERIOUS PLAY tying to a period where everyone has real-time access to abundant data and information, but struggle with making sense of it, let alone connecting individual knowledge to shared knowledge.

In addition, there is a growing need to balance two different but possibly complementary forces: high tech and high touch. We are entering an age where both forces are simultaneously at play. High tech offers a range of virtual solutions to human interaction, from relative simple time/place independent idea generation to virtual reality. Parallel to this, many individuals and organizations are deliberately choosing to focus on the concrete in-person experience of an interaction, aiming to strengthen that interaction's attention density.

We see a balance forming: though there are more virtual interactions and fewer in-person interactions, the demanded outcome of the in-person meetings will be higher than what is often expected today. Attention density has to be high, and there will be a code of conduct stressing that those in the room are immersed in the interaction.

And this demand for the quality of the high-touch meeting is creating three essential needs for which LEGO SERIOUS PLAY works well. You've probably guessed them: going beyond 20/80 meetings, leading in order to unlock knowledge, and the need to break habitual thinking.

The method is designed to counter these challenges and provide added value in terms of enhanced insights, confidence, and commitment. It does this through a unique facilitation approach—a specific set of group dynamics and learning sciences. In this way, it creates a language that connects within and between brains. An essential and very concrete element in that language is the LEGO brick, and the particular way it is used in LEGO SERIOUS PLAY.