Chapter 6

COMMUNICATING IN A DIVERSE WORK ENVIRONMENT

“I do not want my house to be walled in on all sides and my windows to be stuffed. I want the cultures of all the lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any.”

Mahatma Gandhi1

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the role of culture in shaping perspectives.

- Learn ways to succeed in a global environment.

- Appreciate that in life, familiar scripts do not apply in international communication.

- Learn ways to resolve conflicts that arises out of cultural differences.

- Understand methods for interacting effectively in cross-border virtual teams.

INTRODUCTION

Observing a business or social setting in the modern world, one can easily find the presence of many heterogeneous groups. Whether it is a classroom, an IT company, a multinational office, or a business process outsourcing (BPO) unit, globalization has indeed made an irreversible foray into our lives and these heterogeneous groups can represent different countries, cultures, and languages. For the purpose of effective functioning, it becomes imperative that these divergent groups are merged into a singular unit and that is why intercultural communication has gained immense importance in the business world. When varying cultures collide in the workplace, regardless of origin, the mannerisms and habits that the individuals were brought up with and consider socially acceptable can result in friction. This friction can start in personal relationships, but could interfere with productivity and customer relationships.

We are all products of our environment. Our educational backgrounds, religious and political affiliations, and family and social relationships are shaped by the environment in which we are brought up. Our philosophical leanings are powerful determinants of how the world perceives us and how we perceive others. We learn to make choices and communicate accordingly. Ways of communicating with those of different ethnicities and cultures can vary and sometimes lead to miscommunication and misinterpretation. The reason for this is that people from other cultures interpret our signs and signals in markedly different ways. This leads to a communication breakdown. Such a situation may be amplified in business situations where many cultures collide.

Consider the following example. When Nikita Khrushchev, the former President of the erstwhile Soviet Union, visited the United States at the height of the Cold War, he greeted the U.S. press with a clasping of his hands, shaking them over each shoulder. This expression was understood to be a sign of greeting in the Soviet Union, symbolizing the embracing of a good friend. But in the United States, this gesture is understood to be the symbol of a winner in a battle; consequently, the U.S. media interpreted it as a sign that the Soviet Union would be victorious over the United States. This incident only exacerbated the cold war, not dissipating the tension as was the intention of the visit!

Managers must become proficient cross-cultural communicators to succeed in a global environment. Effective managers are able to recognize and adapt to different cultures. This assumes particular importance today as most executives are engaged in international assignments.

As stated earlier, communication means that the message is received, but issues get compounded in a diverse work environment where many cultures collide. This makes it imperative to clarify the two terms culture and communication.

CULTURE

Culture (derived from the Latin word “cultura,” meaning “to cultivate”) is everything that is imbibed, shared, taught, and discussed. Culture may transcend religion. Communication is through shared meaning, which is ascribed to behaviour, words, and objects. Culture is deep-rooted in the psyche; it is complex and often difficult to change.

The term “culture” has two interpretations. It can either refer to the capacity of human beings to classify experiences in the form of symbols or it can mean the distinct ways in which people think and behave in different countries and regions.

Thus, culture has been variously described as a model or a template as well as a medium that we live and breathe in. Culture is learned and innate—an interlocking system. It is a shared relationship and a division of groups. Cultural identities can stem from the following differences: race, ethnicity, gender, class, religion, country of origin, and geographic region. Culture, thus, governs the values, attitudes, and behaviours of people most of the time. It has two main parts (as can be seen in Exhibit 6.1):

- The unobservable, non-material aspect, which is the belief.

- The observable and non-material aspect, which is the behaviour.

Culture is the context to which an individual belongs. Indeed, it is a way of life. Culture influences how we talk, behave, and deal with conflict. Culture is the sociological reality from which few can escape.

Cultural nuances such as attitudes towards hierarchy and status, individualism and teamwork, punctuation, technology, and context are discussed further in this section.

Exhibit 6.1 Composition of Culture

Information Bytes 6.1

In India cultural differences exist widely. This is because of a large ethnic diversity in the population. For example, there is a pronounced difference between the general culture of North India and South India. The Bengali culture is distinctly different from Marathi culture. In fact, each state of India can be treated as a separate country in itself! Apart from linguistic diversity, each state is characterized by specific customs, rituals, traditions, and culinary preferences. All this exists under the umbrella of a secular democratic nation. No wonder India is referred to as having a “salad bowl” culture!

Hierarchy and Status

There are many cultures where rank, hierarchy, and status are given extreme importance. Employees who are new to this culture may find it odd that their attempts to call supervisors by their first names, sit before their supervisors do, sit on chairs reserved for people in senior positions, and so on, are likely to be misinterpreted as disrespect. On the other hand, an employee who has been taught to show deference towards age, gender, or title, might, out of respect, shy away from being honest or offering ideas because offering suggestions to an elder or a supervisor might appear as a challenge to their authority. This dimension is termed as power distance and is the extent to which a society accepts the fact that power in institutions and organizations is distributed unequally.

The view of authority, position, status, rank, and power affects the business environment in a number of ways. In many countries, there is more emphasis on the logic and force of an argument. In others, there is a greater emphasis on the rank and position of the presenter than on the subject matter. This affects the manner in which the message is perceived. In a highly centralized culture, a relatively high-ranking individual's message is taken very seriously, even if one disagrees. On the other hand, in a relatively decentralized system, one can anticipate a greater acceptance of participative management practices.

Teamwork Versus Individualism

There are countries where individualism is frowned upon and teamwork is encouraged. Employees used to such a culture may find it difficult, at least initially, to adjust to an individualistic working style in another country. They may consider people in such countries to be overly independent, self-centered, selfish, and possessing isolationist tendencies. On the other hand, people used to working alone might find another culture to be too dependent on others, slow in making decisions, and incapable of leading an independent life.

Punctuality

Some cultures place a high premium on time. They associate adherence to time with professionalism, high ethical standards, and reliability. Conversely, there are some cultures where time standards are rather relaxed. People in such cultures dislike being hurried and take their own time in making decisions. People used to the former might find the latter to be irresponsible and too flexible.

Most cultures fall into two types of temporal conceptions. The “monochromic” type adheres to schedules; this takes precedence over personal interaction. On the other end of the continuum is the “polychromic” type, where personal interaction, transaction, and involvement take precedence over preset time schedules. Though this is a generalization, by and large, the culture of a state may be described as one of the two in orientation. The main characteristics of these two kinds of culture are discussed in this section.

- Monochronic: A monochronic culture discourages one-to-one interaction and is highly performance-oriented. It also restricts the flow of information and self-disclosure. Personal interactions between people are limited. Personal relationships between colleagues are determined by the terms of the job, and multiple tasks are handled one at a time in a prescheduled manner.

In such a culture, one should expect time schedules to be strictly followed and know that personal favours are not appreciated as far as scheduling is concerned. These cultures rarely distinguish between outsiders and insiders. An example of such a culture is that prevalent in Germany.

- Polychronic: A polychronic culture encourages interaction among people and is characterized by flexibility as far as scheduling is concerned. It is also highly relationship-oriented, where multiple tasks are handled simultaneously by adequate delegation. Cultures in India and Mexico are polychronic in nature.

In polychronic cultures, one should expect delays in meeting deadlines. People may have to be urged to put in their best through motivation, praise, and encouragement. Insiders are generally preferred over outsiders.

Communication Bytes 6.1

The world's expatriate workforce is becoming increasingly female. Women accounted for 23 per cent of international assignees last year. The workforce is also getting younger. According to the 11th annual Global Relocation Trends Survey, issued jointly by GMAC Global Relocation Services and the National Foreign Trade Council, “The 2005 Annual Global Relocation Trends Report” indicates that relocation of non-U.S. personnel to the United States is increasing. 60 per cent of the surveyed companies provided cross-cultural preparation before international assignments. This figure was consistent with previous surveys. 28 per cent provided training for the entire family, 27 per cent for expatriate and spouse, and 5 per cent for expatriates alone. Although formal cross-cultural training was mandatory at only 20 per cent of companies, the lowest percentage in the survey's history, 73 per cent of respondents rated it as having a great or high value in making the assignment a success. India, China and Singapore are the emerging destinations for expatriates.2

Technology

Generally, cultures may be divided into three distinct groups according to their approaches towards technology: control, subjugation, and harmonization.

- Control cultures: In control cultures such as those of northern Europe and North America, technology is viewed as an essential ingredient to control the environment. Technology is employed to improve prospects as well as to enhance productivity. Failures are generally attributed to a technical deficiency.

- Subjugation cultures: In subjugation cultures such as those of central Africa and southwestern Asia, technology is viewed rather skeptically. Technology is subjugated to cultural norms and beliefs, and errors, if any, are attributed to failures in judgment rather than technology.

- Harmonization cultures: In harmonization cultures such as those common in many Native American societies and some East Asian nations, technology is harmonized with the existing environment. These cultures are neither subjugated by technology, nor do they attempt to control it.

Cultural Contexts

Communication, especially in a cross-cultural environment, is largely contextual. Edward T. Hall was the first person to coin the term contexting3. According to him, contexting requires a speaker to decide how much prior information the audience possesses about the topic and communicate based on this assumption. It appears that all cultures arrange their members and relationships along the context scale. One of the important aspects of communication, whether addressing a single person or an entire group, is to ascertain the correct level of contexting of one's communication. A communicator in an international business setting must understand the context of any communication in order to understand what was really meant to be conveyed. The rules vary from culture to culture.

Cultures can be divided into two types based on their approach to providing context:

- High-context cultures: These cultures believe that the meaning is in the messenger and much of what is meant is largely unsaid. Examples of such cultures are Japan, China, Mexico, Greece, the Arab countries, Brazil, and Korea.

- Low-context cultures: These cultures believe that the meaning is in the message and thus communication is generally direct and straightforward. The United States, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Germany, and the German-speaking portion of Switzerland are some examples of low-context cultures.

Apart from these, medium-context cultures include England, Finland, Italy, and France.

In high-context cultures, much of what is not said must be inferred. To people from lower context cultures, this may seem to be needlessly vague. Conversely, those from high-context cultures may view their low-context counterparts as impersonal and confusingly literal. Since contexting represents a cross-cultural shift in the conception of explicit versus implicit communication, any area of business communication in which such distinctions play a part is significantly affected. Thus, in high-context cultures, the emphasis on words in general, and on the written word in particular, is relatively weak since words provide only one aspect of the context of communication. As a result, how something is said matters more than what is actually said. By contrast, in low-context cultures, the actual words matter more than the intended meaning. What is actually said—and especially what is actually written—matters more than the context in which it was said.

Information Bytes 6.2

My Big Fat Greek Wedding is a rather interesting movie from a cross-cultural perspective. One scene, in particular, stands out. During the wedding, when the bride is walking down the aisle, all the guests from the bride's side of the family spit on her as she passes. This cultural expression of good luck by her Greek family is considered offensive and one of worst methods of degradation in American culture. This is just one example of how a simple, heartfelt gesture by people of a particular culture could lead to potential disaster in another one.4

The implications for contexting are far-reaching in the business world. There is considerable emphasis on explicit communication in low-context cultures. This makes the law rigid and inflexible. This is not the case in high-context cultures, where laws are flexible enough to accommodate different situations (how else can one explain the extradition of Warren Anderson, the former chairman of Union Carbide, the company responsible for the worst industrial catastrophe in the world in Bhopal in 1984?). People in high-context cultures, as a result, find that their interpersonal behaviour is governed by individual interpretation (that is, the context of the relationship), while people in low-context cultures find that their relationships are dictated by external rules.

Another dimension of contexting is face-saving. Face-saving implies preservation of dignity and outward prestige. High-context cultures are more concerned with “saving face.” They tend to favour a communication approach that values indirectness and politeness. They may consider directness in communication to be rude and offensive. As a corollary, high-context cultures view indirectness as honest and considerate, while low-context cultures view indirectness as dishonest and offensive. High-context cultures prefer minimal disclosure and tend to remain vague and evasive. This is in sharp contrast to low-context cultures, where preference is given to high verbal disclosure and stating the obvious.

CONCEPTS OF CULTURE

Variations of cultural concepts exist across countries and continents. Some of these concepts include:

- Leitkultur: Leitkultur is the concept of a core culture, where minorities have their own culture but integrate it well with the “core concept” of the nation's culture. The culture of Germany is an example of this.

- Melting pot: A melting pot is where the culture of minorities or immigrants “melts” or amalgamates into the mainstream culture of the host nation. The United States is a melting pot of cultures as it is a host to citizens from diverse nationalities.

- Monoculturalism: Monoculturalism is the concept of a single culture for a single nation. Certain Islamic nations, like Pakistan, celebrate monoculturalism.

- Salad bowl: A salad bowl is a where different cultures maintain their own identities while learning to coexist and interact peacefully within a nation. The heterogeneous culture of India (which has people of different religious beliefs and cultural traditions and at least 22 different languages) is an example of a salad bowl culture.

The word culture might also mean one of the following:

- National/ethnic culture: This is the culture of a nation; an example is Indian culture or American culture.

- Secondary or subgroup culture: This refers to a secondary culture within a larger culture and is also called a co-culture. Examples are organizational culture, Muslim culture, and Hindu culture.

- Culture in the anthropological sense: This refers to how anthropologists delineate the concept of culture. For example, tribal culture is an example of a culture in an anthropological sense.

- High society: This is the exclusive and high-profile reference to culture, such as creative arts like theatre, painting, or sculpture. It might also refer to the sophistication and refinement of an individual.

INTERNATIONAL COMMUNICATION

In a diverse environment, communication is far more complicated than in the simpler model illustrated in previous chapters. Consequently, many employees feel frustrated when their warm smiles are misinterpreted, their informal demeanor mistaken for sloppy work, or their heavy accents confused.

There are many instances of symbols and signs that differ across cultures. For instance, while the “o” sign indicates nothing in most cultures, it indicates money in Japanese culture. When two people of the same gender hold hands, it is of no consequence in one culture (India, for example), but has a different connotation in another. As mentioned earlier, direct communicators (such as Americans) prefer to state things as they are (bottom-line first), but an indirect communicator from another culture might want to take the contextual background into account before trying to understand a certain response.

Communication with different cultures can be understood using the same variables that describe other forms of communication. We tend to judge and predict more when we are communicating with people we are unfamiliar with. We anticipate (but are never completely sure of) the response we will get from a stranger. As we get to know someone, we become surer of the kind of response to expect. Communication improves if people recognize where familiar scripts do not apply and seek to modify their behaviour accordingly.

Direct Versus Indirect Communication

In most Western countries, communication is direct and straightforward. The meaning is explicit and the content gains prominence over context and presentation. However, in Japan, a manager nodding in response to a presentation does not mean that that the manager is in agreement with the presentation. It merely implies that the manager is listening to the presentation.

Accents and Fluency

The international language of business is undoubtedly English. However a non-native speaker's accent, fluency, articulation, and usage of words may create problems and misunderstandings. One frequently cited example of how variations within a single language can affect business occurred when a U.S. deodorant manufacturer sent a Spanish translation of its slogan to their Mexican operations. The slogan read “if you use our deodorant, you won't be embarrassed.” The translation used the term “embarazada” to mean “embarrassed.” This provided much amusement to the Mexican market, as “embarazada” means “pregnant” in Mexican Spanish.

Chain of Command

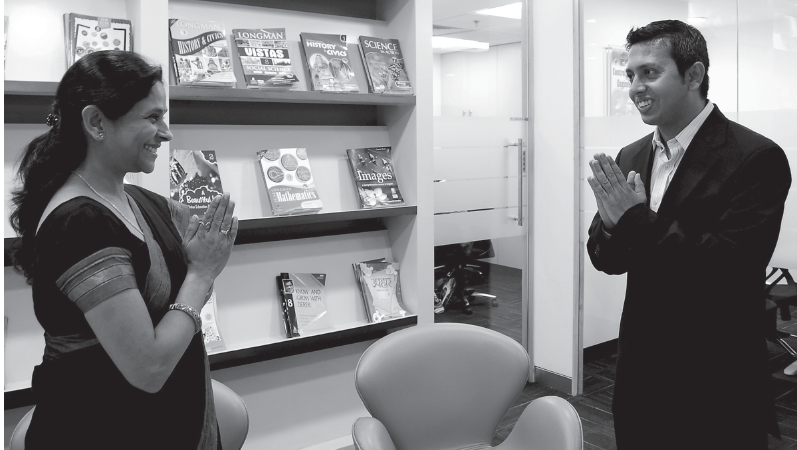

In organizations where the chain of command and hierarchy are rigidly followed, communication is deferential, passive, and slow. For instance, in India as well as Mexico, one is supposed to be respectful and humble when communicating with seniors. Most opinions, suggestions, and so on are put in the form of open-ended questions.

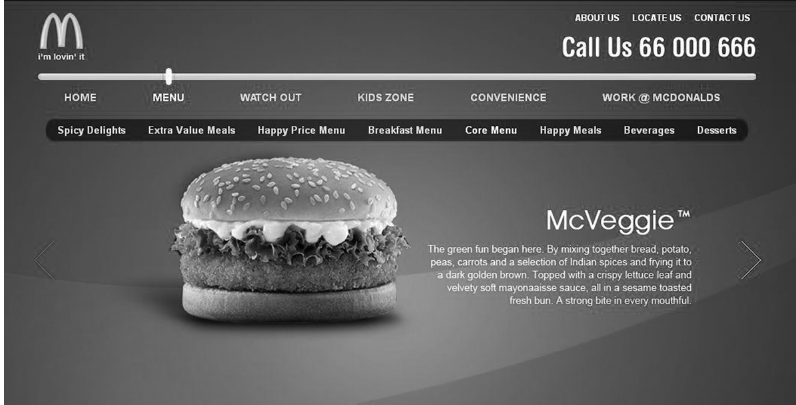

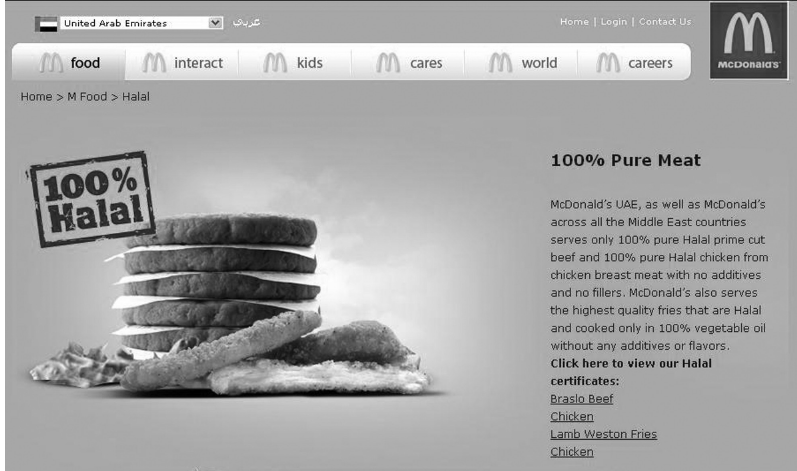

A global organization like McDonald's markets its products according to the culture of each specific country. Because India has a sizeable vegetarian population, McDonald's India prominently advertises its vegetarian fare on its Web site. However, in an Islamic country like the United Arab Emirates, McDonald's chooses to promote its non-vegetarian fare which uses halal meat. (Used with permission from McDonald's Corporation).

Information Bytes 6.3

Cultural differences abound across the globe. A blogger recounts how, as an Indian, she was used to the bossy and strict attitude of the new manager (a German) at her job. However, her Australian colleagues were more used to democratic processes and found the new manager's style to be too authoritarian and dictatorial. The German manager became aware of her situation and gradually adapted the Australian work culture. In short, informal Australian managers are effective in Australia but not in India or Germany, and vice versa.

Physical Aspects

Physical considerations in communication include open and closed office systems, issues of physical space, distance, and proximity, and physical artifacts of culture. For example, there is a sharp contrast between the Western closed office system and the Japanese open office system. In the latter, department heads have no individual offices at all. Instead, their desks are simply one of numerous other desks placed in a regularly patterned arrangement in a large open area. No partitions are used between the desks and no individual offices exist. Yet each person is strategically placed in a way that communicates his or her rank and status just as surely as in the U.S. or French systems. Thus, the department heads' desks are normally placed at a point farthest from the door where they can view their whole department easily at a glance. Moreover, status may also be indicated by placement near a window. The messages communicated by placement in a large open office may be lost on a French or U.S. visitor unfamiliar with the system.

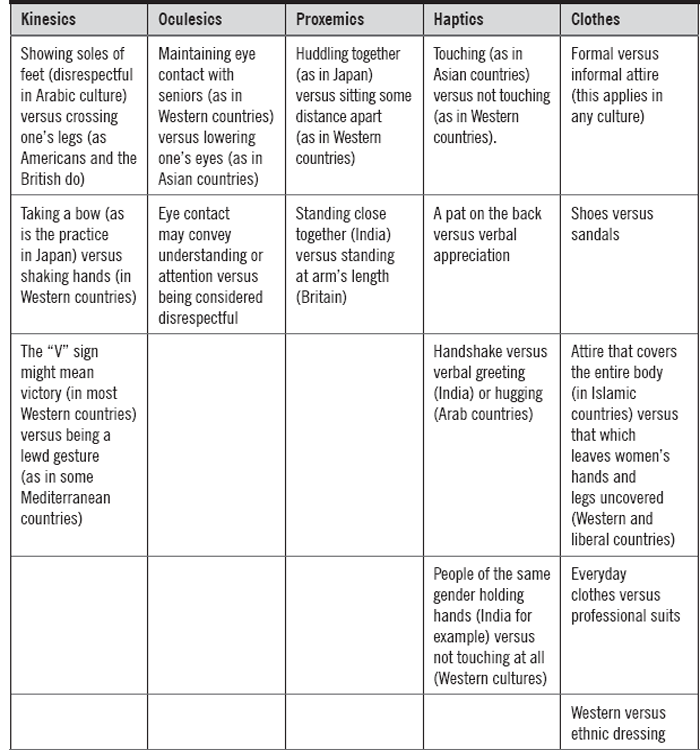

Non-verbal Communication

The words used are only part of any message. Four-fifths of the listener's emphasis is generally on the non-verbal gestures made by the speaker while delivering the message. There are five components of non-verbal communication:

- Kinesics or body language

- Oculesics or eye contact

- Proxemics or the use of body space

- Haptics or behaviour, including touching

- Clothes

Exhibit 6.2 indicates the cultural differences of such signals.

Communicative predictions are based on data from three levels:

- The cultural level: At the cultural level, only information pertaining to a person's culture is ascertained. After gaining knowledge about the cultural norms, one can at least predict some of the individual's responses.

- The socio-cultural level: At the socio-cultural level, information pertaining to the group the recipient belongs to is ascertained. Groups influence individual behaviour to some extent, and the response can be predicted with proper knowledge about the group.

- The psycho-cultural level: At the psycho-cultural level, data about the individual can be gathered from friends and close relatives. At this level, personal habits, characteristics, and other types of data may be gathered to accurately predict the individual's response.

Exhibit 6.2 Non-verbal Signals and Cultural Differences

PROVERBS AND CULTURE

By examining proverbs, one can determine how certain aspects of a culture are viewed. This can relate to attitudes towards women, humility, fate, action, religion, spirituality, aspiration, and ambition as well as characteristics related to work such as professionalism, formality, hierarchy, competitiveness, and pragmatism. Proverbs are cultural indicators. Commonly employed as socialization devices, they are passed on from one generation to the other to perpetuate the cultural orientation of the family, society, and country. Exhibit 6.3 provides a list of proverbs from across the world as well as their meanings.

INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION AND THE WORKPLACE

Intercultural communication in the workplace includes interactions between members of different cultures at the workplace. In organizations, culture affects people's behaviour as well as how they respond to instructions, listen to their supervisors, relate with colleagues, and resolve misunderstandings among themselves.

Exhibit 6.3 Proverbs and Culture

When immigrants stay for a long time in a host country, a process known as acculturation may occur, where traits of the original culture are replaced with those of the host country. This is essentially a group phenomenon. On an individual level, assimilation, a process where immigrants or expatriates adopt the culture of the host country, may occur. However, it is not necessary that these processes occur. In many cases, people prefer to retain their original cultural identity and resist attempts to transform their beliefs.

At times, employees face a situation described as culture shock—the anxiety and apprehension experienced by an individual when he or she operates in a different culture. In these times, the organization must intervene to ensure that the employee is warmly welcomed in the host country and made as comfortable as possible. At least in the initial phase, the organization can do the following:

- Conduct an induction programme for overseas employees. In the induction, the culture of the specific organization, the policies of the organization, and the office jargon and style of business correspondence may be explained to the employee.

- Create an environment free of racism and discrimination. It is the responsibility of the organization to ensure that no embarrassing situations occur due to racist or discriminatory attitudes. At the outset, the managers must ensure that the organization has a zero tolerance policy towards racism and any form of discrimination at the workplace. This will provide reassurance to new employees and help them to adjust to the organization.

Organizational culture is the persona or the identity of the organization. It comprises the values and beliefs of the organization and manifests itself in appropriate behaviours. One can assess the culture of an organization by looking at the interiors of the office, the communication style adopted by the organization, the dress code, the mission and vision statements of the organization, and the accepted rules of conduct. At times of mergers, acquisitions, and organizational transformations, strategic planners need to look not only at the tangible changes to be made, but also at the intangible cultural aspects that should be changed.

Every employee should adapt and try to adjust to each other's cultures.

Information Bytes 6.4

For most people across the world, the weekend comprises Saturday and Sunday. However, for those in the Middle East, the weekend comprises Friday and Saturday, and Sunday is the first working day of the week.

Cultural Conflicts

Cultural conflicts occur when there is a perceived difference in values and beliefs between people from different cultures. The most important barrier to cultural communication is ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism is when people of one culture perceive their culture to be superior to others. They assume that their own cultural norms are the ultimate norms of behaviour, and judge others by the same yardstick. This leads to stereotyping and premature judgments, which affect behaviour and productivity in the long term. There are a few issues one needs to keep in mind while training expatriates for cross-cultural shifts:

- They should be given a basic idea about the new workplace they would be shifting to.

- The style of business correspondence practiced by the country or organization where they are going should be communicated to them.

- An idea about the appropriate kinds of clothes to wear should be given. This is especially important for people who shift from one kind of climate to another.

- Detailed information about the immigration rules is important. It is also good for travelers to follow a few basic rules such as always keeping a photocopy of their passport handy.

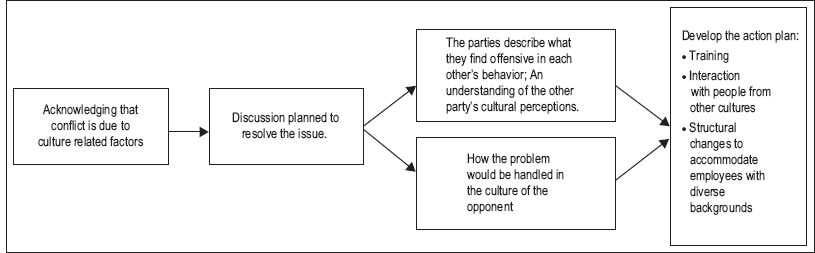

Resolving Cultural Conflicts

With changing demographics, cultural differences have become an important issue in organizations across the world. Many cultural sub-groups resist attempts by the dominant culture to assimilate them into the mainstream culture and desire to maintain their cultural identity. In this scenario, it is essential to educate people about the nuances of various cultures. Exhibit 6.4 illustrates one such process.

Awareness about the importance of cultural differences is important. Acknowledgement that differences exist and are due to culture is the first step in recognizing and dealing with conflict. This acknowledgement should be followed by a discussion initiated by the conflicting parties or via managerial intervention. The discussion should address the following issues:

- The specific offensive action

- Cultural perceptions

- Conflict handling in various cultures

- Best possible solution

Solutions could range from conducting training programmes for cultural sensitization, enabling interaction across cultures by formulating cross-cultural teams, or bringing about a structural change in the organizational setup to accommodate these differences.

Jeanne Brett, Kristin Behfar, and Mary C. Kern have outlined few representative situations and strategies to deal with cultural differences.5

According to the authors, there are four main strategies to deal with cultural conflict based on the situation:

- Adaptation: Some teams find ways to work with or around the challenges they face, adapting their practices or attitudes without making changes to the group's membership or assignments. Adaptation works when team members are willing to acknowledge and name their cultural differences and to assume responsibility for figuring out how to live with them.

- Structural intervention: A structural intervention is a deliberate reorganization or reassignment designed to reduce interpersonal friction or to remove a source of conflict for one or more groups. This approach can be extremely effective when obvious subgroups demarcate the team (for example, headquarters versus national subsidiaries) or if team members are proud, defensive, threatened, or clinging to negative stereotypes of one another.

Exhibit 6.4 A Model for Handling Conflict

- Managerial intervention: The manager should always behave as an intermediary and not as an arbiter or judge in any case of cultural conflict. By involving the team members, both the manager and the team gain in terms of team productivity.

- Exit: When teams are permanent, the exit of one or more members is a strategy of last resort. If nothing else works, this method can be used, either voluntarily or after a formal request from the management. Exit is likely when emotions are running high, too much face has been lost on both sides, and nothing can salvage the situation. Exhibit 6.5 can help us identify the right strategy once we have identified both the problem and the “enabling situational conditions” that apply to the team.

Working across different time zones has become increasingly common. A clash of cultures, especially when the sender and the receiver are not face to face, can lead to unprecedented problems. Different approaches towards time management, meetings, greetings, replies, and e-mails can create confusion and chaos. This can hinder the overall productivity and morale of the workforce.

Exhibit 6.5 Strategies for Resolving Cultural Conflicts

| Representative problems | Strategy | Complicating factors |

|---|---|---|

|

Decision-making differences; Communication differences; Situational conditions Team members can attribute a challenge to culture rather than personality; Higher level managers are not available; Team is embarrassed to involve higher level managers |

Adaptation |

Team members must be exceptionally aware; They must know that negotiating a common understanding takes time |

|

The team is affected by emotional tensions relating to language fluency issues or prejudice; Team members are inhibited by perceived status differences among teammates; |

Structural intervention |

The team can be subdivided to mix cultures or expertise; Tasks can be subdivided; If team members aren't carefully divided into subgroups, it can strengthen pre-existing differences; Subgroup solutions have to fit back together |

|

Violations of hierarchy have resulted in loss of face; An absence of ground rules is causing conflict; The problem has produced a high level of emotion; The team has reached a stalemate; A higher level manager is able and willing to intervene |

Managerial intervention |

The team becomes overly dependent on the manager; Team members may be sidelined or resistant |

|

A team member cannot adjust to the challenge at hand and has become unable to contribute to the project; The team is permanent rather than temporary; Emotions are beyond the point of intervention; Too much face has been lost; |

Exit | Talent and training costs are lost |

An important component of communication is trust. It is easier to build trust in a face-to-face situation. In a virtual situation, the time factor is perhaps the greatest barrier. Business has to be conducted virtually—that is, online—and is purpose-specific. How does one build trust considering the limitations of time and a highly impersonal medium? Again, some cultures do not place a premium on relationship building in business (the United States and Germany are examples), while someone from India or the Middle East may feel awkward plunging straight into business. Thus, in intercultural communication, one should always look beyond the form to the content.

The intercultural complexities that make virtual teams challenging are:

- Language: It is difficult to decipher a foreign language on the telephone or voice mail. Frequent interruptions and clarifications mar conversation. This also hampers productivity. People are not aware of the terms and jargon used in other cultures and may fail to grasp the meaning and intent of the other person. Those who do not speak English as their primary language may misspell words, use short forms, invent new words, use poor grammar, and generally be unclear. Reading an e-mail with such problems can be a struggle, and the meaning of the message can be radically altered with a single out-of-place word. It is important for those communicating across cultures to bear in mind that this is to be expected. The best way to approach such e-mails is to look beyond the form to the intent. If that is not possible, then a simple e-mail should be sent asking for clarification. Another way of dealing with this is to send close-ended questions, which can have only “yes” or “no” as answers.

- Response time: In some cultures, the response time is rather slow and may inhibit communication. A common timeframe should be agreed upon at the very start of the communication.

- Formality/informality: In some cultures, communication is rather deferential. In the time-bound professional cultures, excess formalities are unnecessary. This becomes awkward for the recipient at the other end who believes in the virtues of respect and rapport-building. The best solution is to acquaint oneself with the verbal and non-verbal nuances of the other culture; understand and be considerate of the “otherness” of the team members; and get to know the other team members before getting down to business.

Working Your Way Out of Challenges

The following suggestions might be useful when trying to successfully deal with a multicultural team:

- Try to bring together all members of the multicultural team physically, at least once in a while. If this is not possible, try to arrange a videoconferencing session where members see and interact with one another.

- Formulate clear ground rules for the following engagements:

- Rules for written communication

- Rules for processing responses

- Rules for conflict resolution

- Rules for personal conduct during meetings

- Guidelines for decision-making

- Set clear-cut team objectives and share them with everybody else.

- Ask everybody to write something about their own culture, in particular their style of working, customs, beliefs, and ways in which they deal with conflict. Have an informal sharing session.

- Celebrate important festive occasions of each culture in a small way.

- Follow up with written communication so that everyone is on the same footing.

- Create a zero-tolerance policy for any form of racism and discrimination.

Information Bytes 6.5

In May 2007, Kwintessential Ltd., a leading intercultural communication consultancy, announced the launch of three new Google gadgets. These were the translation quote gadget, the free e-mail translation gadget, and the intercultural business communication gadget. With these innovations, users across the world can simply choose their language and enter the words to get their quotes. The free e-mail translation gadget allows users to send e-mail to anyone in German, French, or Italian. The third tool offers practical tips to users across the world on overcoming cross-communication difficulties.

Source: Based on material taken from <http://hailgadget.com/2011/04/intercultural-communication-firm-launchesnew-google-gadgets/>, accessed on June 3, 2011.

SUMMARY

- Culture is the context to which an individual belongs. Indeed, it is a way of life. Culture influences how we talk, behave, and deal with conflict. Culture is the sociological reality from which few can escape.

- Globalization, immigration, and international tourism have led to a large number of people being engaged in cross-cultural interaction. This has increased people's desire to understand the cultures of other countries as well as the norms of cultural interaction.

- Attitudes towards time, physical proximity, and forms of communication differentiate one culture from another.

- The biggest barrier to cultural understanding is ethnocentricity—the feeling that one culture is superior to another.

- Cultural conflicts can be resolved through adaptation, structural intervention, and managerial intervention strategies, with someone exiting being the last option.

ASSESS YOUR KNOWLEDGE

- “Communication serves not only as an expression of cultural background, but as a shaper of cultural identity.” Explain this statement in light of the impact of culture on communication and vice versa.

- “Low-context communication may help prevent misunderstandings, but it can also escalate conflict because it is more confrontational than high-context communication.” Explain the differences between low- and high-context cultures.

- How can cultural awareness enable managers to communicate effectively in organizations? Explain giving examples.

- Why is ethnocentrism considered to be the most important barrier to cross-cultural communication?

- Enumerate the four ways managers adopt to deal with cross-cultural communication conflict. Why is adaptation not always the best way out?

- Describe the process of resolving conflicts in a typical global work setting.

- How do idioms and phrases used in a country represent the culture of that country? Explain with examples.

USE YOUR KNOWLEDGE

- You represent an Indian firm. You have been asked to prepare a presentation on doing business in Japan. What aspects of Japanese culture would you incorporate in your presentation?

- The following cross-border mergers and acquisitions have taken place recently. What aspects of each culture, according to you, should be taken into account for a smooth transition of the parent company into the host company?

- TATA Chemical acquires U.S.-based Soda Ash Maker General Industrial Products for USD 1 billion.

- Indian shipping company Great Offshore acquires U.K.-based Sea Dragon for USD 1.4 billion.

- Essar Energy acquires 50 per cent stake in Kenya Petroleum Refineries Ltd.

- Banswara Syntex acquires French firm Carreman Michel Thierry for USD 125 million.

- Investigate cultural issues relating to the merger between a) HP and Compaq, and b) Chrysler and Daimler-Benz. What strategies may be adopted to deal with cultural conflict at the workplace?

WEB-BASED EXERCISES

- Refer to the following link: <http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/cross-cultural_communication/>. What does the author mean by “face saving” as an important cultural variable?

- Refer to the following link: <jcmc.indiana.edu/vol11/issue1/wuertz.html>. Read the article by E. Wurtz named “A cross-cultural analysis of Web sites from high-context cultures and low-context cultures.” Comment on the manner in which McDonald's has used the Internet for online marketing.

- On January 27, 2006, Lakshmi Mittal, head of the world's largest steelmaker, shocked the world by announcing a surprise hostile takeover bid valued at USD 23 billion (EUR18.6 billion) for his largest rival, Europe's Arcelor. Critically analyse the cultural issues in the Arcelor-Mittal merger. Refer to the following link for help: < http://www.slideshare.net/robvandamm/arcelormittal-merger-case-cross-culture-management.>

FURTHER READING

- A. Williams, “Resolving Conflict in a Multicultural Environment” MCS Conciliation Quarterly (Summer 1994).

- D.A. Victor, International Business Communication (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1992).

- E.T. Hall, The Silent Language (Greenwich, CT: Fawcett Publications, 1959).

- F. Trompenaars and C. Hampden-Turner, Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Cultural Diversity in Global Business (New York: Irwin, 1998).

- G. Hofstede, Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (London: McGraw-Hill, 1991).

- William Gudykunst and Young Yun Kim, “Communicating with Strangers: An Approach to Intercultural Communication,” in John Stewart, ed., Bridges Not Walls, 6th edition (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995).