A system is a set of interdependent parts which together form a unitary whole that performs some function. Essentially, the parts must be interdependent and/or interacting. A heap of components may form a ‘whole’ but not necessarily a system unless arranged, say, to form a machine. Any system can be shown to be a sub-system of some larger system. Thus a carburettor is a sub-system of the car engine and a sub-sub-system of the car itself.

In order to understand how a system fulfils its function, it is useful to know how all its parts are related to each other and how the system is to be linked to the larger system that constitutes its environment. The way a watch measures time can be deduced by knowing how its parts are related to each other and the way it conveys time can be deduced by studying how it is used—that is, by studying the watch/user relationship.

This discussion raises two important questions. How are the boundaries of any system determined? What are its appropriate sub-systems? The answer to both questions depends on the purpose of the analysis, and incorrect answers can lead to errors. Take, for example, the design of a machine such as a lathe. It is common to treat the machine itself as the system. In consequence, inadequate attention is given to the physical limitations of the human operator. Ergonomists today speak of the ‘man-machine’ system to emphasize that the system often consists of both man and machine, and consequently machine parts such as levers and dials need to be designed with human physiology in mind. In another sphere, those engaged in analysing clerical procedures emphasize that each procedure must be looked at as a whole so that the needs of all users are adequately considered. An order-handling procedure is interdepartmental and must be designed to serve the needs of all the departments concerned with order handling—production, sales, accounting and so on—it should never be designed purely with one department in mind.

Many national controversies are in part arguments over the appropriateness of the system. Is it possible to make a study of national transport needs by a study of railway economics in isolation? Can one study the training of physicists and chemists by studying merely their education at university level and ignoring schools? Even where people are agreed about the purpose of an analysis, there may still be debate over system. The difficulty or cost of dealing with the complexity of a larger system may make for the acceptance of something less than ideal. A case can usually be made out for studying some larger system. Thus Susan Stebbing, a logician, commented on physics:

In order that physics as a science should be possible, it is necessary that we should be able to consider some characteristics in isolation from other characteristics. It is in fact the case that physicists have been successful in regarding the physical world as separable into small systems, and into sub-systems of those systems, with respect to which physical statements can be made. It may be true that

Thou canst not stir a flower

Without troubling of a star,

but it must be admitted that no one stirring a flower has ever succeeded in observing the consequent troubling of a star. Astronomers have prosecuted their researches in the confident belief that in turning their telescopes upon the moon they have in no way affected that which they are observing.’103

This debate over system is not merely academic. To study too wide a system for the purpose at hand is wasteful, but to study too narrow a system may lead to sectional efficiency at the expense of the total system. If a particular system seeks to achieve certain objectives at minimum cost, it is not likely to do so by seeking separately to minimize cost for each of the sub-systems, since overall minimum cost may necessitate high cost in one sub-system to achieve low cost elsewhere. For instance, a motor manufacturer might reduce the cost of piston rings by increasing their production and consequently spreading the fixed costs: but unless he can simultaneously make more pistons and cylinder blocks he will only increase the overall cost by accumulating an expensive surplus. It is the interdependence of sub-systems from the point of view of the purpose at hand that necessitates the overall approach.

The purpose of an analysis also determines which sub-systems are appropriate. If we wish to understand how a watch works, it is of little value to study how the gold parts are arranged in relation to the brass parts if they are purely ornamental. In studying a watch as a mechanism, aesthetic aspects are irrelevant. However, in any study of the watch as a marketable commodity, the system would include the watch's appearance as one important sub-system.

THE SYSTEMS APPROACH TO ORGANIZATION

The systems approach emphasizes that for any investigation there is an appropriate system to be studied, and the purpose of the investigation decides both the boundaries of the system and the appropriate sub-systems. If the investigation concerns company organization, what is the system to be studied? The organization of the company is a means to achieving its objectives. Thus the system must embrace both the company itself and that part of the external environment, for example the market, that impinges on objectives, so that these can be set as a basis for organization. What are the appropriate sub-systems to be studied? The sub-systems chosen centre on the main decisions to be made to accomplish objectives. The organization should be designed to facilitate decision-making, but since decisions depend on information and information on communication, the organization is built up from an analysis of information needs and communication networks. Decision-making is chosen rather than activities or departments because it is through the process of decision-making that objectives and policies are laid down and actions taken that result in company success or failure.

The systems approach to organization consists of the following steps.

1. Specifying objectives.

2. Listing the sub-systems, or main decision areas.

3. Analysing the decision areas and establishing information needs.

4. Designing the communication channels for the information flow.

5. Grouping decision areas to minimise the communications burden.

Devising a system that pursues the wrong objectives solves the wrong problem. This may be far more wasteful than choosing a system that fulfils objectives inefficiently. A company that sets an objective purely in terms of volume sales may devise the ideal marketing campaign to achieve this objective but may go bankrupt while doing so. The problems involved in specifying objectives have already been discussed. Despite the difficulties encountered, setting company objectives is essential if guide lines are to be provided for decision-making throughout the company.

LISTING THE SUB-SYSTEMS, OR MAIN DECISION AREAS

In listing the decisions that are to be made within a company, a difficulty arises in that all problems cannot be anticipated, so that appropriate decisions cannot always be predicted. Another difficulty lies in determining the unit of decision since almost every decision is part of a system of decisions. As Simon illustrates:

‘The minute decisions that govern specific actions are inevitably instances of the application of broader decisions relative to purpose and to method. The walker contracts his leg muscles in order to take a step; he takes a step in order to proceed toward his destination; he is going to the destination, a mail box, in order to mail a letter; he is sending a letter in order to transmit certain information to another person, and so forth.’104

The unit of decision is a matter of judgment depending on the purpose and therefore the detail of the analysis. The problem is illustrated in the case study (Appendix I).

ANALYSING THE DECISION AREAS AND ESTABLISHING INFORMATION NEEDS

Decision-making means making a choice from a range of possible courses of action. Managers aim to be efficient at making decisions, that is, choosing the alternative which, as far as they can tell, will give better results as measured by their objectives than the alternatives displaced.

It is not immediately apparent that decision-making is any problem. Superficially, it appears to be merely a matter of getting the facts on the grounds that when these have been examined the right solution or decision will automatically present itself. Decision-making is usually more complex than this. Many important decisions have to be made without knowledge of all the facts and are often more akin to acts of faith. Decision-making deserves detailed study since the success of a company depends on the quality of its decisions.

Effective decision-making depends on how well the following steps are carried out.

Establishment of Goals

Like the company itself, every decision seeks to further some goal or objective. A decision on inventory level might seek to choose the level which minimizes the costs of carrying inventory plus the costs of running out. Decision goals, like company objectives, can be multiple and conflicting. However, since all goals are meant to further company objectives, conflicts need to be resolved by choosing those goals that will best further these objectives. In practice, it may be difficult to show explicitly the relevance to company objectives of decisions made lower down in the organization, such as decisions on leave of absence.

The choice of a wrong decision goal means that the wrong problem is put forward for solution. A sales manager may be simply given the goal of increasing turnover by 10 per cent. If literally pursued, the attainment of the goal might lead to unprofitable sales, which may not have been the intention of those who laid down the goal. An interesting example of the importance of defining the right goal or problem to be solved was mentioned by Mountbatten in an interview recorded in The Observer Colour Supplement, September 6th, 1964, in referring to the work of Sir Solly Zuckerman:

‘Solly had been asked to work on the general problem of how much bombing was required to “silence a battery”. Being a scientist, and a man with a very logical and original mind, he asked a question which nobody seemed to have asked before: “What does ‘silence’ mean? Does it mean drop a bomb on every gun, and put it out of action, does it mean knock out the men firing the guns, or what?” His point of view was, you can't answer the question “What is required to silence a battery?” unless you can define what you mean by “silence”.

‘What Solly found, in a nutshell, was that if you knocked out one-third of the guns only, by that time the noise and the blast, the disruption of communications, and the general alarm and excursion had such an effect on the morale of all the troops in the vicinity that you had virtually silenced the whole battery. On this basis, Pantelleria was far from being impregnable. He was right. We took it with a loss of only three men.’

Identifying possible Courses of Action

The essence of decision-making is that the manager has to make up his mind which course of action to choose. However, the posing of different courses of action for consideration is not straightforward. Simon points out that they are not usually given but must be sought, so it is necessary to include the search for alternatives as an important part of the process of decision-making. The words ‘searching for alternatives’ seem a little misleading as this suggests that the decision-maker already knows what he is looking for. This may not be true. Hence it may be better to speak of the ‘process for identifying possible courses of action.’

Since the process for identifying possible courses of action determines what is considered, it is also a factor in determining the quality of the decision finally taken. A manager may simply adopt what others have done in like circumstances and not worry about identifying possible courses of action. The danger is that standard solutions are installed when conditions are far from standard and goals are distorted to suit the solution. The processes for identifying possible courses of action range from ‘brainstorming’ to sophisticated management techniques such as those of Operational Research. Management techniques are becoming more and more important in identifying alternatives. For example, one company wished to increase its sales of men's socks. The different courses of action suggested by reflection were to have a ‘sock sales week’ and/or increase expenditure on advertising socks. A market analysis, however, showed that the company only catered for about 15 per cent of the men's sock market and might profitably consider producing ‘fancy socks’ and socks at another price level.

Identifying Consequences

Every course of action will have a set of consequences if chosen. Again, the consequences attached to alternatives are seldom given but have to be identified. Often only major consequences are listed and side-effects ignored. In particular, the side-effects on morale of decisions made within a company have tended to be ignored.

Knight, the economist, has suggested a classification of the conditions under which decisions are made.105 Decisions can be made under conditions of certainty, risk and uncertainty. A decision under certainty occurs if each possible course of action has a unique outcome. In these conditions, choosing among outcomes or consequences is the same as choosing among the possible courses of action. If the courses of action can also be ranked in order of preference, decision-making is made routine. A decision under conditions of risk means that more than one possible outcome or set of consequences is associated with each course of action, but that probabilities for the outcomes can be stated. Finally, decision under conditions of uncertainty means that more than one possible outcome is associated with at least one of the different courses of action but that probabilities for the outcomes cannot be stated. It is doubtful whether managers ever feel that they make decisions in conditions of complete uncertainty. In fact, specialist advice might increase the manager's uncertainty when making a decision by showing the decision to be more complex than previously envisaged. Shackle, another economist, speculates that in conditions of uncertainty the manager ‘feels’ out his experience and chooses a course of action that causes him to feel some degree of certainty that no unpleasant surprise will occur.

The management sciences have developed an operational language for expressing risks and techniques for measuring it. Of particular importance is the application, since World War II, of mathematical and statistical techniques to management problems, aided when necessary by electronic computation. However, Simon argues that ‘many, perhaps most, of the problems that have to be handled at middle and high levels in management have not been made amenable to mathematical treatment, and probably never will.’ Simon also considers how to improve the problem-solving capabilities of humans in ‘non-programmed’ situations and how computers might be used to aid managers in problem solving without first reducing the problems to mathematical or numerical form.106 Ashby's work on the mechanization of thought processes is also relevant to this problem.107

All the management sciences seek to provide information to reduce uncertainty. If a new product is launched without any market analysis, the decision is made under conditions of uncertainty. The information resulting from a market analysis and pilot venture could reduce uncertainty and transform the decision into the category of risk.

The more decision-making can be simplified, the more it can be formalized, in which case the decision may either be delegated or sufficiently programmed to be passed on to a computer. Decision-making is also simplified by formulating policy, since information on policy removes a great deal of uncertainty within the organization. Policy can be regarded as a set of rules for reaching a decision. Where such rules can be developed, consistency in decision-making throughout the organization is more likely and time is saved because less reference is made to superiors.

Managers seek to reduce uncertainty in decision-making. Galbraith, the economist, even argues that ‘the development of the modern business enterprise can be understood only as a comprehensive effort to reduce risk.’108 He criticizes theoretical economists who assume managerial behaviour to be explained simply in terms of a need to maximise profit. Managers may in fact sacrifice additional profit in favour of certainty. The results of an investigation by Meyer and Kuh109 would tend to support Galbraith. They found that businessmen favoured the internal financing of capital investment and tended to limit this investment to the amounts that were available within the company. They tended to ignore the market rate of interest and business opportunities that could only be financed by external borrowing. It is argued that this behaviour occurs because the consequences are far more serious if an externally financed investment fails than if the investment is internally financed. However, an equally plausible explanation is that people carry over into business life their personal dislike of borrowing.

Establishing Criteria for Evaluating Consequences

The decision goal determines the criterion for evaluating the various sets of consequences. There is a need, however, for measuring the extent to which an event furthers objectives. A common unit of measurement is necessary to resolve conflicts. Without it, one cannot compare, say, the alternative that leads to lowest distribution costs and the alternative that achieves shortest delivery time. Unfortunately, all consequences cannot be expressed precisely in terms of their effect on cost and profit so there may be difficulty in using money as the common unit of measurement. This may lead to a complex problem of value measurement which has been the concern of Von Neumann and Morgenstern.110

Establishing Decision Rules

If consequences are evaluated by predictions of their effect on profit, it would be consistent to choose the alternative that is likely to add most to profit. The answer may not be so easy. There is the problem of the conflict which might arise between long- and short-term profit expectations. There is also the difficulty of relating profit to risk and uncertainty. A low profit with low risk may be more acceptable than a high profit with high risk. Profit expectations alone may not tell the whole story. Certain of the alternatives may have consequences which are not susceptible to measurement but none the less can be very important. The manager may choose not the ‘best’ alternative as judged on quantitative grounds but some other alternative that he considers is more likely to further his goals.

Example

The decision process as described above can be illustrated by a simple example. A company wishes to increase its profits by introducing a new product. Alternative products are considered. The managing director asks for likely sales on the two products. Sales department claims that 150,000 units of Product No. 1 can be sold but only about 100,000 units of Product No. 2. However, questioning reveals that the forecasts are not certain but contain an element of risk and sales forecasting produce ranges of possible sales and attached to each range the probability of actual sales falling within that range. The costing department calculated net profit on the assumption that the mean of each range was likely to be the actual level of sales if sales fell within that range. The managing director then decided that of the two products he would select that which was likely to yield most profit overall. Fig. 26 gives all the basic data. Profit expectation is found by multiplying the probability figure by the net additional profit figure and the total profit expectation is simply the sum of the products. On the basis of the data in Fig. 26 the managing director would choose Product No. 2 which gives the highest profit expectation. However, the difference in profit expectation between the two products is so slight that other non-measurable considerations might lead to Product No. 1 being chosen instead of Product No. 2.

|

Anticipated Sales |

Probability (a) |

Net |

Profit |

|

|

|

|

£ |

£ |

|

Product |

30,000 |

0˙2 |

4,000 |

800 |

|

No. 1 |

90,000 |

0˙25 |

8,000 |

2,000 |

|

|

150,000 |

0˙3 |

12,000 |

3,600 |

|

|

210,000 |

0˙25 |

16,000 |

4,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

—— |

|

| Total 10,400 | |||||

|

|||||

Product |

20,000 |

0˙l |

3,000 |

300 |

|

No. 2 |

60,000 |

0˙l |

8,000 |

800 |

|

|

100,000 |

0˙5 |

10,000 |

5,000 |

|

|

140,000 |

0˙3 |

15,000 |

4,500 |

|

|

|

|

|

—— |

|

| Total 10,600 | |||||

A final comment on decision-making lies in Simon's argument that no manager explores all alternatives but terminates his search when a satisfactory rather than a best solution has been discovered. (‘Always be content with the third-best solution. The second-best comes too late and the best never comes at all’—A. J. Rowe.) The manager's behaviour is ‘satisficing’ rather than maximizing. Alternatives are separately sought and evaluated and the search to identify further alternatives is only continued if no alternative is found to be satisfactory. The cost and difficulty of identifying alternatives and the urgency of the solution will have a bearing on what is considered satisfactory.

Information Needs

The discussion on the decision process itself is important. It shows how decisions can be simplified, which is important when determining the level to which decisions can be delegated. Furthermore, the discussion has shown that the quality of decision-making depends on the quality of the information available as well as on managerial judgment. Information to management has been said to provide the same function as headlights to the night driver. The headlights illuminate the road ahead but do not rule out the need for good judgment. The informational system does affect organizational planning. It ought to influence the level at which delegation takes place. Also, since information needs to be communicated, it determines the communication network, which, in turn, is facilitated or hampered by the organization structure. Finally, informational requirements may necessitate the setting up of specialist departments whose job it is to provide the appropriate information to management. Such specialist departments need to be integrated into the company and so affect any organization plan.

A planned management information system has as its goal an integrated system of reports that gives each level the ‘right’ information at the ‘right’ time so that decisions are based on the best information available, as far as the provision of such information can be justified on economic grounds. There are a number of different approaches to an information system. One approach is to design quicker ways to process data. This approach is useful in situations where information needs are well established and speed has some merit, for example in accounting, records for legal purposes, or an air-raid warning system, but is not very helpful in situations where information needs are only vaguely known. Another approach is to increase the amount of data available. This approach can often lead to the collection of useless information. Another approach is to examine existing reports for duplication and so avoid the situation where sales and production (say) are producing the same statistics. This approach may merely reduce the cost of doing the unnecessary. Finally, managers may order certain reports to be discontinued and only re-introduce them when individuals protest. This approach may lead those who have been deprived into producing their own unofficial records and reports. The most fundamental approach is the ‘decision approach’ which consists of specifying the decisions to be made and then determining information requirements. This is the more logical approach since the purpose of information is to facilitate decision-making. All information systems must be tailor-made to suit specific circumstances and each report forming part of a management information system should satisfy criteria as to relevance and adequacy, cost in relation to usefulness, timeliness, accuracy and precision, and presentation. Relevance and Adequacy. All decision-making is concerned with formulating plans or controlling the execution of plans. Hence, information is needed for either planning or control. Planning looks ahead to determine what is to be done while control currently establishes whether plans are being or are likely to be achieved.

If an existing or proposed piece of information or report is to be useful in planning it must facilitate one or more of the steps taken in making a decision by

(i) providing information on goals,

(ii) identifying the alternatives or ruling out a whole class of alternatives formerly thought possible,

(iii) showing the consequences likely to arise from adopting an alternative,

(iv) helping to evaluate alternatives.

If an existing or proposed information system is to be adequate for planning purposes, it must be concerned with the major uncertainties—that is, concerned with the uncertainties in the main decision areas as deduced from objectives, past company history and forecasts.

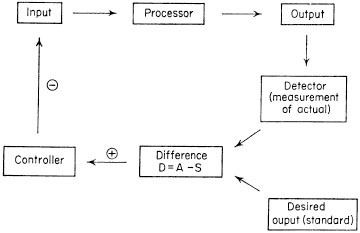

When plans are formulated, expectations are laid down about the conditions which must exist if the plans are to be satisfactorily carried out. Each expectation is termed a ‘standard’ and the difference between actual achievement and standard is calculated as a basis for control. Thus, let actual achievement = A and standard = S, then A – S=D, the difference. If D is outside acceptable limits, either actual performance is above or below what might reasonably be expected, or expectations were set too high or too low in the first place. Control is being exercised wherever this comparison is made between what is happening and what was intended if the purpose is to reduce the error between the two. Thus if S refers to the anticipated cost of a product or a process, it is termed standard cost and D is the variance. If S refers to the anticipated cost of a department or the company as a whole it is referred to as a budget and the formula D = A – S represents the process of budgetary control. There are many other control systems and all possess an underlying unity of concept which is not always recognized. The systems analyst in describing this unity uses a number of terms which may be unfamiliar, many being taken from control engineering.

The measurement and comparison of actual with standard and subsequent corrective action is referred to as ‘feedback’. Technically, feedback means transferring a portion of the energy from the output of some device back to its input to achieve control. It can be regarded as checking on the output of some process and controlling the input to the process in accordance with the effectiveness of the output as judged against standard. Such an arrangement in which the input depends on feedback from the output is known as a ‘closed-loop control system’. If the feedback reduces the error, that is the difference between actual and standard, rather than aggravates it, the feedback is termed negative. Positive feedback aggravates the error.

Fig. 27 is a model of a closed-loop system with negative feedback; the model is more descriptive than that represented by D = A – S. It could represent a machine with a built-in control mechanism such as a thermostat regulating the temperature of a house. The input is the labour and fuel needed to keep the furnace going. The processor is the furnace itself and the output is the heat entering the room. The thermostat would include some mechanism to detect the actual room temperature. If the thermostat dial were set at 70°, this would be the desired output or standard. Where the actual temperature varies from 70° some controller switches the furnace on or off. The system would be closed-loop or closed-cycle because the input of labour and fuel depends on the actual output of heat. If the input were modified as a result of directly sensing the actual disturbing influences outside the house, the system would be ‘open-loop’. Open-loop systems may be more effective in certain business situations since, unlike error-regulated systems, they can achieve perfect control in theory.

FIG. 27.—A closed-loop system with negative feedback.

The model in Fig. 27 is general and could even represent overall company control. Inputs would be labour, orders, materials, capital and information. Outputs would be products and services to customers and dividends to shareholders. Company objectives would express the desired outputs. Control would seek to nullify the random effects of fluctuating orders, material supplies and to detect and pursue trends as a basis for revising objectives.

Controls serve a number of specific purposes.

(a) They foster delegation. A reluctance to delegate may be traced to a fear of losing control, reinforced by the knowledge that delegation does not mean being absolved from blame in the event of failure. Budgeting in particular, of all management control systems, has been instrumental in fostering delegation and facilitating decentralization. As the economist Neil Chamberlain comments:

‘The neoclassical school of economists believed that the one sure curb on the expansion of any company was a marginal cost curve which was bound to rise, sooner or later, due to the inability of all factors to increase proportionately; and that the factor which, of all factors, was most certain to be the limiting one was management. More labour and more capital might be added in equal doses, preserving their proportionality, but management—particularly the top-level entrepreneurial type of management—by its very nature had to remain fixed, or relatively fixed, thereby eventually leading to diminishing returns: the job of overseeing the expanding firm would require management to spread itself thinner and thinner, becoming less and less effective, until rising costs would put an end to its growth. The process of budgeting, with its potentialities for decentralization, no longer makes this expectation so certain. At a minimum, it increases very considerably the size to which a firm may grow before diminishing returns set in. The weight of detail under which it was believed that top management's effectiveness would be smothered has been distributed to others farther down the organization; the necessity for close supervision has been lightened through the concepts of budgetary responsibility and management by exception.’111

(b) They save managerial time. Controls save managerial time by focusing attention purely on significant deviation from plans.

(c) They provide feedback for planning. Past performance helps shape future aspirations and those who do not learn from the past tend merely to repeat their errors. This point emphasizes the fact that the same information may be used for both planning and control purposes.

(d) They measure performance. Because controls measure performance they are often resented. However, such accountability for performance is the factor that facilitates delegation. As management has already found in budgeting, if such resentment is to be avoided without abandoning accountability, then those being controlled should be encouraged to participate in setting standards.

In examining the usefulness of information for control purposes we need to determine whether:

A. The information is complete. Is each of the quantities in the equation D = A – S available? It is frequently the case that standards have not been laid down either implicitly or explicitly during planning and information is merely available on A, the actual state, and management is left to control on this basis. Without standards there can be no control though standards may be implicit—they may exist but may not be available for reference.

B. The standard has been set correctly. Standards may be based on ‘forgotten guesswork’. Any standard should fulfil the following conditions.

(i) It should be reasonably attainable, since a standard represents the conditions that exist if a job is carried out satisfactorily. Standards set too high either cause anxiety or tend to be treated with contempt. Standards set too low tend to breed premature satisfaction and complacency.

(ii) It should be based on certain conditions for its attainment. If these conditions change, so should the standard. Where alternative conditions may be operative then alternative standards may be developed. This is the reasoning behind flexible budgeting; an appropriate expense budget, for example, is developed for each range of possible output levels.

(iii) It should correspond to responsibility. Someone must be made accountable for variation from standard if control is to be effective.

(iv) It should be limited to key activities. Often controls are based on factors that are easy to measure, rather than key. For example, time cards may be the only information that an office manager receives (apart from the limited amount received through visual observation) as to the efficiency of the clerks under him. In such circumstances, it is not surprising that the clerks feel that good time-keeping is mainly what is demanded of them. We cannot possibly control all factors in a situation; control over minor factors dissipates energy.

(v) It should be based on best analysis available. Ideally, standards are based on analysis and measurement and so generate the need for measurement (for example merit rating). However, descriptive standards can in certain circumstances be effective, for instance standards of military dress, and past performance (which may be the only guide, as in the field of labour relations). The setting of standards for any particular activity improves with experience but initially management may have to make do with crude approximations.

(vi) It should be based on results rather than method. It is better to set standards on results rather than method; the way the job is done being left to the man himself. In this way self-control is likely to be encouraged and periodic accountability is substituted for close supervision. However, control over results may be too remote or even be impossible, so that control over method becomes essential. In the field of advertising, control must be on method, for example media selection, because the end-results of advertising cannot usually be measured, in the short period, in terms of resulting sales. In such circumstances the standard constitutes a criterion and represents the conditions that exist when the job is being carried out satisfactorily.

C. The control information is structured. The various levels in an organization should not receive identical control information since this may bring with it a tendency for superiors to duplicate the work of subordinates. Villiers argues that control reports for the various levels of management should be comparable but related in the same way as an atlas is related to an ordnance survey map.112 Only the controls reaching the executive with responsibility for taking action should give details of variation from standard. For the executive charged with taking immediate action, the difference or error, D, needs to be broken down and analysed into its constituents but executives at higher levels simply wish to be informed of the variation. If the higher executive wants the details, these are readily available. As an example, a managing director may simply know that costs have risen in factory ‘A’ The manager of factory ‘A’ may know that costs have risen because department ‘X’ has made excessive scrap during the period under review. Only the foreman in the department knows the various reasons for this excessive scrap as it is his immediate responsibility to take remedial or corrective action. If all levels were to receive the details, they may be overburdened and neglect work that is more pertinent to their immediate responsibilities, or they may be inclined to suggest remedies before the subordinates are given an opportunity to take action. Of course, if unacceptable variations persist between standard and actual, it becomes the responsibility of higher levels to take action.

The PERT/Cost system used for controlling weapon development in the USA provides a perfect example of structured control information.113

Cost in Relation to Usefulness. A report or any other piece of information cannot be justified simply on the ground that it is useful for planning or control purposes. Its cost must not exceed the likely benefits derived from its use. The total expenditure on information that is justified on economic grounds will vary from company to company and will also depend on the availability of management techniques for reducing uncertainty. A large firm can usually justify a greater expenditure on providing information than a small firm in the same line of business. A company with a thirty million pound turnover is more likely to justify a ten thousand pound annual expenditure on marketing surveys than a company that only has half a million turnover. However, two companies of such a difference in size might justifiably spend the same amount on information if the smaller company was in a line of business where uncertainty was high while the larger company had a monopoly in selling a standard product to an assured market.

The efficiency with which uncertainty can be reduced depends, among other things, on the development of management techniques. As techniques are discovered and prove their worth, more is spent on securing the services of specialists who use their techniques to produce improved planning and control information.

Information should not be distributed randomly to all and sundry. Cheap duplication of information and the enormous output capacity of the modern electronic computer have tended to encourage the widening of distribution lists while the cost of sorting, filing and reading information has tended to be ignored. Although too little information may lead to wrong decisions, too much information is wasteful of resources and often means that relevant items of information are overlooked in an information jungle.

Timeliness. Information should normally be provided when the best use can be made of it. Although speed should not be sought for its own sake, information consistently late may be useless or lead to action that is inappropriate to a new situation that has developed meanwhile. In the example of the foreman and his scrap, reports on scrap levels which reach him too late cause scrap to accumulate before remedial measures are taken. On the other hand, there is no point in producing information faster than it can be used unless originating it earlier reduces its cost.

Accuracy. Accuracy should not be sought for its own sake. There is often a conflict between providing figures that are accurate to the nearest penny and providing data on time and in a way that is operationally useful. Time is often wasted in computational work by taking figures to an unnecessary degree of accuracy. For sales statistics it may be possible to ignore shillings and pence when the resultant error is insignificant for the purpose.

Presentation. Some engineer once said that the impact of a report depended not only on the weight of its contents but also on the speed with which its message is put across. Good presentation should aim at bringing the significant facts into focus in a language familiar to the reader. A detailed discussion of presentation is outside the scope of this book but there are a number of good books on the subject.114

DESIGNING THE COMMUNICATION CHANNELS FOR THE INFORMATION FLOW

Communication is the means by which information is passed from one person to another and can be carried out by gesture, talk, instrument or written word. It is through communication that information is passed to the decision-maker and resulting decisions passed to those involved in executing them. Without communication there could be no organization since it would be impossible to get people to act in a co-ordinated way; people would be linked together by an abstract chain of command but acting without a chain of understanding. Where communication is poor, co-ordination is poor since co-ordination implies that people are being informed about each other's plans. Furthermore, co-operation presupposes co-ordination so that co-operation itself depends on communication.

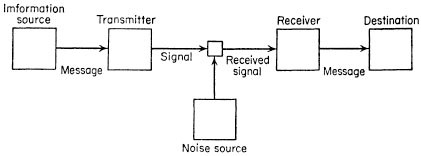

An elementary communication system is shown overleaf.

The information source is the origin of the message. The transmitter converts the message into signals and transmits the signals to a receiver over a communication channel. The receiver converts the signals back into a message which is passed over to its destination. The words ‘transmitter’ and ‘receiver’ are here used in a general way, and include such instruments as typewriters, tape recorders, telephones and even the shorthand notes taken down by a typist. The noise source adds an interfering signal to the message signals. Noise can be defined as any addition to the signal which is not intended by the information source, such as distortions of sound or error in transmission. The word ‘noise’ is used in a technical sense. It may coincide with common usage in a telephone or radio message, but also embraces a stenographer's errors in shorthand and typing, misprints by a teleprinter, or even misinterpretations of a spoken sentence. In oral speech the information source is the brain, the transmitter is the voice mechanism, the communication channel is the air, the receiver is the ear of the listener and the destination is the brain of the listener.

FIG. 28.—(Diagram, Shannon and Weaver.115)

Noise is other sounds that make the message difficult to hear. Redundancy occurs when there is more information in the message than is strictly necessary, for example when each word of a message is repeated. Some redundancy is usually desirable to correct any errors that might occur in the transmission of a message. The redundancy in the English language aids the listener to identify from the context words that otherwise might be misunderstood. For example, the sentence ‘Gd sv the Qn’ would be correctly interpreted as ‘God save the Queen’.

Weaver distinguishes three problem areas in communication.

‘Relative to the broad subject of communication, there seems to be problems at three levels. Thus it seems reasonable to ask, serially:

Level ‘A’ How accurately can the symbols of communication be transmitted? (The technical problem.)

Level ‘B’ How precisely do the transmitted symbols convey the desired meaning? (The semantic problem.)

Level ‘C’. How effectively does the received meaning affect conduct in the desired way? (The effectiveness problem.)’116

Weaver also states that:

‘The mathematical theory of the engineering aspects of communication, as developed chiefly by Claude Shannon at the Bell Telephone Laboratories, admittedly applies in the first instance only to problem A, namely the technical problem of accuracy of transference of various types of signals from sender to receiver.’117

He goes on to note, however, that ‘the theory of Level “A” is, at least to a significant degree, also a theory of levels “B” and “C” ’.118

Problem level ‘A’ is not so important as yet in organization work as to justify full discussion though Shannon's information theory has been applied in work organization.119, 120 The problem levels ‘B’ and ‘C are more relevant but the theory is very much in its infancy.121 Hence this section will confine itself to a general discussion on communication channels.

The line of communication between two people or two organizational units is the communication channel. Thus A—B indicates that communication exists between units A and B. As this connection does not show whether the communication is one way or two way, it is common to add arrow-heads to indicate the direction of communication. Thus A ↔ B would indicate that the communication is two way while A→ B would mean that communication is merely from A to B. Where several units are linked together by several channels, a communication network is established. A communication network relates people to each other and top management to every unit in the business. An analogy can be found with the human nervous system. The brain cells are linked up with every organ and every tissue of the body through the nerves. Each nerve (or channel) has its special work to do. Some carry messages to the brain, and others, messages from the brain to the cells. The brain receives and examines the information and sends off answers, although much routine decision-making has already been delegated to other parts of the nervous system such as the ganglia. It is interesting to note that any muscle that is cut off from all communication with the brain quickly dies unless the connection is restored.

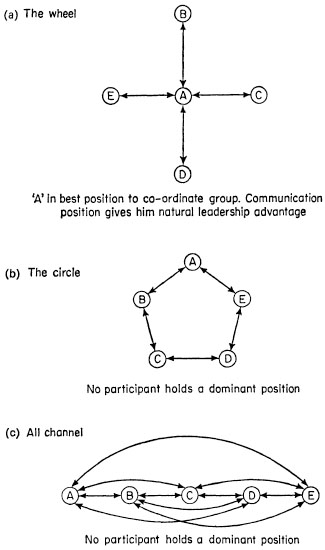

Drawings a-c in Fig. 29 show various communication networks for a group of five people. The question arises as to which network is best. Laboratory experiments undertaken by psychologists Bavelas and Leavitt122 suggest that the ‘wheel’ is faster if the problem to be solved is straight-forward, but that the ‘all-channel’ network stimulates high morale and adaptability and encourages accuracy. Likert, with his overlapping work group form of organization, is recommending the all-channel network since this would represent the work group in conference. Committees are generally all-channel unless the chairman insists on all communication being routed through him.

FIG. 29.—Communication networks.

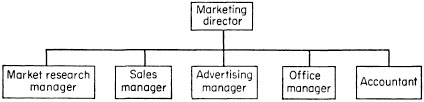

‘A’, in the wheel, is in the best position to co-ordinate the group. The group are dependent on him regardless of the formal authority he possesses. He may impede or speed up group activity and, since he acts as a filter, he can also influence the attitudes of members to each other. Too many channels may mean that ‘A’ is overloaded. The wheel may be inappropriate where the group is required to solve a problem that depends on cross-fertilization of ideas. Suppose the marketing director below has to decide market strategy

What communication network should be adopted? The all-channel would be the most appropriate, since the participants will all have ideas of their own which need to be discussed by the group as a whole so that ideas are ventilated and conflicts resolved. On the other hand, if the marketing director merely has to decide the date of the annual sales conference, the wheel would be more appropriate since the director may simply require information from his colleagues as to convenient dates.

A network can be examined in much the same way as information reaching the manager can be examined.

(i) A network may be inadequate. Someone may be missed out of the network who should not be; salesmen may not be informed about a proposed advertising campaign, though such information may be necessary to planning their sales appeals.

(ii) The channel itself may be overloaded; taking the telephone service as an example, this may necessitate

(a) increasing the number of channels;

(b) queueing; on this point Rowe comments as follows:

The flow of information can introduce time lags into a system as a result of queueing effects. In a sense, information flowing through a number of decision makers is comparable to jobs flowing in a factory or cars flowing on the highways. For example, if the decision-maker is viewed as a processing centre, the rate of arrival of decisions and the time taken to make the decision will determine the average delay or queueing effect. If appropriate priorities are assigned the various decisions to be made, it is possible to both improve effectiveness and reduce delay times. Another means of reducing delays is to have alternate channels for the given decisions. Filtering or screening decisions is still another means of reducing the flow time through the system123;

(c) accepting a higher error rate unless messages can be made clear in the first place, since redundancy as a means of avoiding errors may not be possible.

(iii) A network can be examined for economy.

(a) Distribution lists may be too wide.

(b) The information source and destination could perhaps be located nearer to each other.

(c) The channel itself may not be the most efficient available.

(iv) A network may also be too slow. Transmission times may be calculated for each channel and the total time compared with that desirable as a basis for considering other networks. Forrester of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has shown how internal delays in communication can produce oscillations in outputs and stock levels which may be wrongly attributed to environmental factors.124

GROUPING DECISION AREAS TO MINIMIZE COMMUNICATIONS BURDEN

As specialization increases, interdependence increases and with it the need for co-ordination. How much interdependence can be tolerated without giving rise to a serious failure in coordination, assuming that the people concerned are willing to co-operate? The answer depends on:

1. Channel capacity. The information capacity of a channel is the maximum rate of transmitting information that is possible through the channel. The greater the channel capacity relative to communication needs, the greater the tolerance for interdependence.

2. Stability of interdependence. The more stable the work relationships between organization units, the greater the tolerance for interdependence since stability facilitates prediction, so coordination may be achieved by a plan and this reduces the need for subsequent communication. In an example given earlier, it was argued that sales training could be carried out by the personnel department because co-ordination by plan was possible. The syllabus, etc., could be agreed, say, each year between sales and personnel staff and there would be no need for them to keep in constant touch with each other. Where relationships are in a state of flux, co-ordination must be achieved by constant feedback since the unpredictability of events rules out planning in advance.

The systems approach lays stress on minimizing the communications burden to improve co-ordination. Grouping people under a common superior and putting them physically close to each other may reduce the communications burden and, therefore, may be one way to improve co-ordination. Looking at the company as a whole, if co-ordination is the goal, then groupings should be chosen which lead to more self-containment than alternative groupings; information sources, decision and action points most dependent on each other are grouped together. The pattern of interdependence between units may also be made more stable by grouping units under a common superior so that co-ordination is improved by having all units subscribe to a common plan.

Some writers aim at a broad systems approach without the detailed analysis of decisions and information flows as described above. For example, Rice speaks of his Import—Conversion—Export model, derived from open systems theory which he describes as follows:

‘When a complex enterprise is differentiated into parts, the sub-systems that carry out the dominant import-conversion-export process, that is perform the primary task of the enterprise, are the operating systems. Generally, there are three kinds of operating systems:

(a) import—the acquisition of raw materials;

(b) conversion—the transformation of imports into exports;

(c) export—the disposal of the results of import and conversion.

In simple organizations there may be incomplete differentiation and one operating system may carry out more than one part of the total process, or even all of it; in complex organizations there may be more than one operating system of each kind. Most organizations will contain a mixture of both simple and complex structures.’125

Further descriptions of his model might be summarized as follows:

Where there are several products, there may be several major operating systems (subdivision on the basis of major differences in sources of raw material), several conversion systems (subdivision on the basis of differences in technology or process sequence), and several export systems (subdivisions on the basis of the differences in distribution). Each operating system, too, can be further subdivided into smaller discrete systems in that each has its own primary task and hence its own dominant import-conversion-export process (in other words each is a system in its own right and so could be further subdivided on the basis of its having an input which is processed, and an output which results from the processing). Since a system external to the operating systems is required to control and service them, there is also a need for a managing system which contains management plus the control and service functions (such as finance, personnel, and research and development). Rice refers to his initial division of an enterprise into operating systems and a managing system as the first order of differentiation. Where the operating systems and the managing systems are further subdivided, the result is second-order of differentiation; further subdivision leads to third-order of differentiation, and so on. Control and service functions come under the management within whose area the functions exclusively operate.

The main criticism of this approach by Rice is that it is at too high a level of generality to be useful in detailed organization planning. In fact, it differs little from the approach put forward by some ‘classical’ writers who argued that the first step in company organization was to define the operational departments which were, generally, Purchasing (Import), Processing (Conversion) and Distribution (Export), and then to distinguish the specialist departments who help management to co-ordinate and control these operational departments. Furthermore, they argued that grouping within these divisions could also then be carried out on the basis of grouping together those activities that came nearest to serving common goals.

THE SYSTEMS CONTRIBUTION TO CLASSICAL ORGANIZATION PROBLEMS

GROUPING INTO DEPARTMENTS AND HIGHER ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS

The systems approach is mainly concerned with grouping to achieve co-ordination. The approach recommends listing the main decision areas within a company and determining the information needed for the decision to be made effectively. Activities may then be grouped to minimize the time spent in communicating this information. Co-ordination is thus facilitated by having the ‘right’ information communicated to decision-makers with minimum delay arising as a result of the organization structure.

The time spent communicating information is not usually the sole criterion used by systems analysts in considering the problem of grouping. The decisions that give rise to the communications are considered.

1. It may be undesirable to group together specialist staff, such as quality control experts, and decision-makers whose functions are directly affected by their recommendations, as this may result in limiting the activities of the specialist staff as well as affecting their objectivity.

2. Speed in communicating information is more vital in some decision areas than in others. In the event of conflict between alternative groupings, speed must be taken into consideration.

Most companies are organized on a functional basis; each department is devoted to some function—production, marketing, and so on. This type of departmentalism is not appropriate in all circumstances and some firms have moved over to what is termed ‘project management’. This can be regarded as divisionalization on the basis of project. The firms adopting some sort of project management—the British Aircraft Corporation is one of them—generally fall into the following categories.

(i) They are engaged in designing and building large plant or machinery to customer specification.

(ii) They depend on product innovation since the products they produce are quickly obsolescent.

(iii) The product or project is technically complex and requires a great amount of development work by a number of different technical specialists.

(iv) The product or project must be produced to a rigid time schedule to meet customer specification or market demand.

Firms falling into one or more of the above categories are likely to find a major problem in co-ordinating activities on a project. In these circumstances, a company organized into functional departments may find its organization is slow, cumbersome and inflexible. The specialists concerned with some project need to be brought together, not scattered widely throughout the departments. They also need to give their undivided attention to one project so that their contribution can be relied on. They may also need to be placed under a common superior responsible for the overall direction of the project.

The situation may be looked at from a systems viewpoint. The need for co-ordination on a project may be far greater than the need for co-ordination between projects. Alternatively, co-ordination between projects can be planned well in advance whereas co-ordination on a project requires day-to-day consultation among those concerned with it. The information required for the successful completion may be much less concerned with what is happening on other projects than with what is happening on the project itself. Communication networks, if drawn, would be distinguished on a project basis. Project management thus leads to grouping those decision areas most dependent on each other.

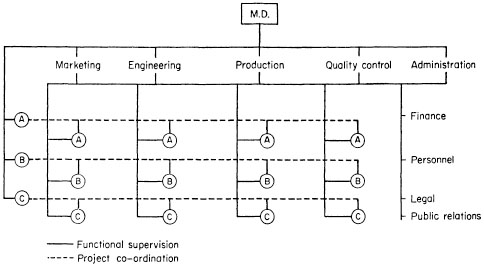

The need for project management has often been indicated by the use of network analysis126 but has sometimes led in the first instance to the matrix type of organization as shown in Fig. 31. In this form of organization, the specialists concerned with the project report both to a functional boss and to a project co-ordinator. The specialist is both a member of a functional group and also of a project team.

The matrix organization does not always lead to the degree of project control considered necessary, and conflicts may arise between the functional manager and project co-ordinator. As a consequence, firms may move on to project management where the specialists are allocated to a project for the duration of its life and are answerable only to the project co-ordinator until the project is finished. The aim has been to make the project team as self-contained as possible. This may result in duplication and under-utilization of resources, but such waste may be a reasonable price to pay for achieving co-ordination.

FIG. 31.—’Matrix’ organization.

Companies do not go to the extreme in project management but retain some functional departments as some overall company direction is necessary. Furthermore, to split all departments on a project basis (the legal department is a good example) may be manifestly less efficient than retaining some departments to serve the company as a whole.

Project management has been effective in achieving co-ordination on a project; in developing strong teamwork and teams which identify themselves with project goals. However, there still remains the problem of setting these advantages against the following losses.

(i) Under-utilization of resources in order to achieve self-containment of projects.

(ii) Failure to achieve some economies of scale.

(iii) Failure to achieve co-ordination of functions company wide. There is a difficulty in maintaining standards of proficiency and uniformity of practice among specialists who are no longer controlled by a common head.

(iv) Insecurity among project members since project teams are disbanded on completion of a project.

To summarize, organizing on a broad functional basis helps in achieving economies of scale and company wide co-ordination of functions but the problem of co-ordination within departments and/or between departments is made difficult. Project management simplifies co-ordination on a project but may fail to achieve economies of scale and company-wide co-ordination of functions.

Workload

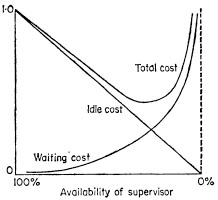

On the subject of assessing managerial work load, Rowe argues that an economic span of control could be determined as shown in Fig. 32.

FIG. 32.—Distribution of economic span of control. (From A.J. Rowe, ‘Management Decision Making and the Computer’, Management International, 2/1962, by permission of Betriebswirtschaftlicher Verlag.)

‘Since the supervisor is a decision processor, an economic span of control could be determined as shown in Fig. 32. If the supervisor is always available (no subordinates), there would be a high idle cost; however, if there were too many subordinates, decisions would be held up due to the supervisor being unavailable. This leads to a high waiting cost. Thus, the correct span of control would consider the cost of delays in decisions on the entire business. Since the waiting or queueing effect increases exponentially, it appears that there is an optimum availability of the supervisor which can be related to the span of control.’127

Rowe is rightly pointing out the queueing aspects of the work load problem since it may not pay to cater for peak work load conditions. However, his exposition is inadequate as it ignores, like the classical approach, the fact that a manager carries out work other than that arising through having subordinates.

DELEGATING AUTHORITY

Communication can be from the information source to the decision-maker or from the decision-maker to the point of action. If the information source and the point of action are fixed, then the communications burden can only be reduced by varying the point of decision. In these circumstances, the delegation of decision-making authority assumes major importance in organization. Also, unless it is known who makes what decisions it is not possible to determine the distribution of information.

Network Centrality

Communication networks provide an insight into the problem of allocating decision-making authority. As Simon states:

‘The possibility of permitting a particular individual to make a particular decision will often hinge on whether there can be transmitted to him the information he will need to make a wise decision, and whether he, in turn, will be able to transmit his decision to other members of the organization whose behaviour it is supposed to influence.... An apparently simple way to allocate the function of decision-making would be to assign to each member of the organization those decisions for which he posesses the relevant information. The basic difficulty in this is that not all the information relevant to a particular decision is possessed by a single individual.128

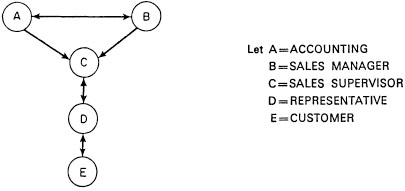

As an extension of these ideas in simple problem solving, decision-making tends to gravitate to the person at the centre of the communication network.

Suppose, for example, the above network is appropriate for making a decision about closing an account on economic grounds. All the executives in the network have some information to contribute which is relevant to the decision, but who should actually make the decision? In this simple instance, a good case can be made out for allowing the decision to be made by the person in the centre of the network; calculated as follows. First, all links or channels through which a person must go to communicate with someone else are added up. Thus, in the case above,

For ‘A’ AB = 1, AC = 1, AD = 2, AE = 3, making 7 in all.

For ‘B’ BA = 1, BC = 1, BD = 2, BE = 3, making 7 in all.

For ‘C’ CA = 1, CB = 1, CD = 1, CE = 2, making 5 in all.

For ‘D’ DA = 2, DB = 2, DC = 1, DE = 1, making 6 in all.

For ‘E’ EA = 3, EB = 3, EG = 2, ED = 1, making 9 in all.

The totals add up to a grand total of 34. This grand total is divided by each individual total to find the centrality of each position. On this basis,

A's score is 4˙9

B's score is 4˙9

C's score is 6˙8

D's score is 5˙7

E's score is 3˙8

In cases where the ‘right’ decision depends on information being supplied by all participants, and the decision is almost self-evident when all such information is assembled, then the correct decision can be made quickest by the person with the highest centrality score. In the case above it is C, the sales supervisor, so all information should be sent to him to make the decision.

There are many limitations to allocating decision-making authority in this way.

(a) All decision-making is not of the problem-solving variety where the decision is a simple inference from facts supplied by all in the network. In the case above, for example, B may bring to bear on the information supplied by others an experience that would not be elicited unless he had looked at all the information together. This is particularly true in cases where the decision to be made is of a qualitative nature.

(b) The approach assumes that each participant has the same amount to contribute to the solution of the problem. It may well be that one participant has most of the information with which he is already familiar. Even though this person may not be in the centre of the network, it may still be quicker for him to make the decision since any other person in the network would have to assimilate the bulk of information already held by him.

(c) Even where decision-making is in the nature of simple problem-solving, speed in decision-making is not the only factor that should be considered. Cost affects the choice of decision level as well as speed. In certain cases it may pay for a decision to be made at a level lower than that indicated by the centrality position on the ground that the loss in speed is more than compensated by the saving in cost. Ensuring the quality of policy decisions may also outweigh considerations of speed; the repercussions from an error in decision-making, if great, may lead to the decision being made at a higher level than suggested by the centrality position.

(d) The network only considers the making of the one decision. Decisions, when made, are conveyed to others to help them make their decisions, but the person in the best position to make a decision may not be in a best position to communicate it to others.

(e) The highest centrality score may be obtained by a specialist but it may still be advisable for the specialist to remain purely advisory.

In determining the point at which each decision should be made, the systems approach takes into account the factors mentioned by the other approaches.

The classical approach would consider

1. the cost of decision-making at various levels,

2. the decreased cost or increased effectiveness resulting from economies of scale and/or improved co-ordination.

The human approach would tend to concentrate on decision-making in certain cases by work groups.

However, the systems approach re-emphasizes the fact that co-ordination is improved if communications are improved and decision-making can be speeded up if the decisions are made at the point where the communications burden is minimized. This occurs, in certain cases of simple problem solving, at the position which is the centre in the communications network.

In project management, the project co-ordinators are man-aging teams of specialists. The problem of who makes what decision is almost always determined by the team members’ speciality. There is probably no need for much formality. Similarly, there may be no need to specify how a man should do his job, since he is a professional, though he still needs guidance on objectives. Also, the responsibilities of the project manager and his team are often made clear without formal schedules, since attached to the projects themselves are defined budgets, goals and time schedules. The project team recognizes its responsibility for meeting these targets. The lack of formality is avoided not because formality encourages rigidity, but because authority and responsibility are made clear in other ways.

SPECIFYING RESPONSIBILITY OR ACCOUNTABILITY FOR PERFORMANCE

Appendix II shows how decision-making authority might be allocated in a way that pays attention to information and communication requirements, and at the same time indicates the subtlety of the decision-making process by recognizing, for example, that many decisions result from team work though the final decision may be taken by one man. This schedule has been successfully used in practice but varies in format to suit particular circumstances. The one shown is designed and completed for the marketing department of ‘Strongwear’; a company used as a case study at the end of this section. The first three pages show the allocation of authority over field salesmen and the rest of the schedule shows the allocation of authority for the main marketing decisions. The abbreviations used are explained on the schedule. The column headings are as follows:

(i) Decision Area. In this column are entered the decisions to be allocated. The size of decision unit is a matter of judgment depending on the extent to which decision-making is likely to be diffused in an organization. For example, in some companies the three separate decisions listed under ‘Work Methods’ might be combined into one decision—’determining work standards’.

(ii) Makes Recommendations. Into the column ‘makes recommendations’ is entered the title initials or code number of those who, through having undertaken no specific study of the decision in question, should nevertheless be in a position to make recommendations because of their general experience. They are specifically encouraged, by being included in the schedule, to make suggestions as part of their job.

(iii) To be Informed After Decision Made. Into this column is entered the title initials of those to be informed after the decision is made to allow them to carry out their own work.

(iv) Information Source. Relevant information improves decision-making but obtaining such information may involve consulting others or reports produced by them. However, the information source limits the range of discretion open to the decision-maker. The decision-making may in fact be purely nominal and routine as when the superior gives such close direction that he lays down not only the decision goal but also how alternative courses of action are to be sought and evaluated. At the other extreme an information source may be purely advisory, as, for example, when the Market Research Manager gives advice to the Marketing Director. Somewhere in between the information source simply gives direction on goals. In this schedule a superior can never be in the position of ‘advisory only’ to a subordinate decision-maker as advice from a superior is really direction. As Brown points out ‘clearly, if a manager gives “advice” to a subordinate, he expects it to be accepted, and he cannot escape the responsibility for having done so. Advice is a confused way of giving an instruction.’129

(v) Makes Decisions. Although emphasis has been placed on simplifying decisions, there are also cases where circumstances change and make decision-making more complex. As a consequence, although the making of a particular decision may, as a general rule, fall within the province of a particular executive, there are always circumstances where the executive's good sense tells him that he should refer the decision ‘upstairs’. Hence, it is realistic to divide the column ‘makes decisions’ into the two categories shown—those who usually make the decisions and those who only do so in exceptional cases.

(vi) Appropriate Information. Into the column ‘appropriate information’ can be entered the titles or numbers of those documents that are relevant to the decision. Where no information is available, one should ask whether it should be provided.

ESTABLISHING RELATIONSHIPS

The systems approach emphasizes decision-making and communicating appropriate information to the decision-maker. In the process, the way people are linked together for the purpose of making some decision is revealed. Showing the way people contribute to various decisions in this way also makes explicit their formal relationship to each other.

WORK ORGANIZATION

More and more, teams of workers carrying out mainly physical activity are being replaced by machines tended by one or two controllers. The ergonomist specializing in systems work is concerned with the design of these man-machine systems. The emphasis is not on how work should be shared out among workers but on how work should be divided between man and machine. The ideal division changes as technical advances are made; man can still read handwriting better than any machine though this may not always be so.

The division of work between man and computer is of particular current interest. The ideal division in this case does not, however, depend simply on advances in technology but on the extent to which decision-making can be formalized. Where decision-making can be reduced to following a set of rules, it can be made into a routine and handed over to the computer. In such circumstances, though, it may be more logical to regard the decision-maker as the man who makes the rules while the computer may be regrded as merely supplying answers.

As decisions are simplified they can be delegated to lower levels in the organization. On the other hand, it has been argued that the use of a computer may bring with it a tendency to centralization. This is not necessarily so. A computer may provide information that was not previously thought possible and may thus simplify decision-making, allowing it to be pushed downwards. Furthermore, the ICI Mercury computer at Wilton is connected to other divisions all over the country by teleprinter links. This principle is being extended in modern timesharing computers, which are large machines capable of accepting several quite different jobs and scheduling their performance within the machine.

The more decision-making is simplified, the less the opportunity for exercising judgment. Hence there appears a possibility of conflict between decision simplification and job enlargement. This is to confuse job enlargement with making all work non-routine. Thus Simon comments:

‘Implicit in virtually all discussions of routine is the assumption that any increase in the routinization of work decreases work satisfaction and impairs the growth and self-realization of the worker. Not only is this assumption unbuttressed by empirical evidence but casual observation of the world about us suggests that it is false. I mentioned earlier Gresham's Law of Planning—that routine drives out non-programmed activity. A completely unstructured situation, to which one can apply only the most general problem-solving skills, without specific rules or direction, is, if prolonged, painful for most people. Routine is a welcome refuge from the trackless forests of unfamiliar problem spaces. The work on curiosity of Berlyne and others suggests that some kind of principle of moderation applies. People (and rats) find the most interest in situations that are neither completely strange nor entirely known—where there is novelty to be explored, but where similarities and programs remembered from past experience help guide the exploration.’130