Chapter 7

Getting Up Close and Personal with Customers

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Taking a wide-angle view of markets

Taking a wide-angle view of markets

![]() Comparing good customers with bad customers

Comparing good customers with bad customers

![]() Investigating your competitors’ customers

Investigating your competitors’ customers

![]() Looking closely at customer behavior

Looking closely at customer behavior

![]() Creating loyal customers

Creating loyal customers

Getting to know the neighbors is a fine way to make for a happier home life. And for business? More than almost anything else, how well you know your customers ultimately determines how successful you are in your business plans.

But we’re the first to admit it: Not all neighbors can be ideal. In fact, some can be the proverbial ones from Hades. So how do you figure out what makes good or bad neighbors — or customers — tick? It can be downright frustrating. In your business plans, you may be tempted to throw up your hands and leave the entire mess to the so-called experts — marketing gurus, consultants, or perhaps astrologers. Don’t. This chapter shows you how to acquaint yourself with your customers so that you can offer them more value and serve them more profitably than anyone else in your industry.

We compare good customers with difficult customers and try to help you gain some insights from your competitors’ customers as well. We take a closer look at why customers buy your products and services. And we examine customer perceptions and decision-making processes. We consider ways to develop loyal customers by improving customer service, and we take a quick look at other businesses that invest in your products or services.

Keeping Track of the Big Picture

By now everyone knows about missing a forest because of too much attention to individual trees. When you first start to think about your customers, you don’t want to fall into a similar trap. Focusing on a small number of individual customers and their personal habits, likes, and dislikes is both tempting and easy. But stop right there! Don’t view your customers and your business activities too narrowly. Look instead at the larger forest, or at least that patch you’ve identified through market segmentation — the customer behaviors and basic needs that define your addressable market (see Chapter 6 for more info on defining market segments).

General Motors’ Cadillac used to be the luxury car in America. Everyone knew you were the man if you were seen behind the wheel of one of these highway yachts. Forty years ago it outsold its nearest rival by a five-to-one margin. But nothing stands still forever. Buyers aged; a new generation of drivers hit the road; and foreign automakers began to target this emerging segment with styles and features more suited to the demands of this new generation of upscale customers. Lured by the intense loyalty of its customer base and the high margins they were willing to pay, Cadillac was frozen in the past; the inside joke was that its customers’ average age was between 65 and death. In 2020 Cadillac’s market share was barely 7 percent of the luxury market.

Unfortunately, companies (and even entire industries) lose sight of the big picture all the time. Companies view markets too narrowly and neglect customer needs — a classic management blunder. Keep the big picture in mind, and chances are you’ll recognize strategic market opportunities. Charles Revson did when he revolutionized the cosmetics industry. Revson famously quipped, “In the factory, we make cosmetics; in the store, we sell hope.” As the founder of Revlon, he understood that he offered his customers something far more important than simple chemistry: the prospect of youth, beauty, and sex appeal. Boy, talk about sizzle!

Numerous firms in other industries also began to understand that they were selling what some called the “enhanced product.” These included gas stations. Proprietors realized that they had a captive audience who actually didn’t want to be there at all, but the demands of a fossil-fueled motor engine required the periodic stop. So why not sell them something in constant high demand, relatively small in size, and quick and easy to pick and purchase? Indeed, why not! Today almost 85 percent of gasoline vendors are, in fact, small convenience stores carrying a limited variety of FMCGs (fast-moving consumer goods) like packaged snack foods, beverages, tobacco products, and the like. Gasoline sales generate less than 3 cents per gallon profit to the store owner.

Winemakers reached a similar conclusion. The product itself is relatively complex with few, other than experts, understanding the science that differentiates bad or excellent from good. Some of the more astute winery proprietors realized there’s more to wine than the juice itself: If managed right, it could become an “experience” product. Many people today, especially younger consumers, want some fun associated with the buy process. And that’s what they began to get at the winery: facility tours, tastings, gift shops (some with goods actually related to wine), and access to the site for events such as weddings, anniversaries, or corporate meetings — all available for a fee.

Categorizing Your Customers

Buyers of goods and services are influenced by many factors. These are internal in some instances — how people are raised, such as their exposure to powerful forces like religion or politics or education. The rising field of neuroscience is also finding evidence that genetics can determine personality traits, just as it does your physical appearance or eye color. (“Isn’t it weird how Mariah is just like her mom when it comes to being so considerate to others?”) But external forces also have a strong influence on behavior, which is something you should be aware of when you consider your customers and their attitudes toward your firm and its products.

Comparing generations

When you were born, believe it or not, is often a major driver of customer behavioral attitudes. Market researchers have identified five demographic generations that define people, as follows:

- The Silent Generation — born 1928–1945

- Baby Boomers — born 1946–1964

- Generation X — born 1965–1980

- Millennials — born 1981–1996

- Generation Z — born 1997–2012

People born into these generations were exposed to different events that shaped their worldview, including attitudes toward technology, politics, social norms, and economic life, among other categories. They bring these views to their evaluation of what you offer in the marketplace today:

- The Silent Generation (increasingly silent as the clock ticks away) experienced the Great Depression as children or teenagers. Cataclysmic events had a profound influence on this group’s attitudes toward economic security and social stability.

- The storied “Boomers” — more than 75 million of them — were raised in relative affluence compared to their parents, enjoyed educational opportunities unheard of before, and reflected a joyful optimism about the future. Can-do, by golly!

- The Gen Xers, however, about 65 million strong, came of age in a very different time as the American Dream began to unravel through tragic events like Vietnam, civil rights battles, and a growing political divide. Skepticism began to replace optimism. Try telling an Xer that they could go to the moon and their government could solve problems.

- Next are the 72 million Millennials — far more liberal in their social attitudes than prior generations, quick to embrace diversity and pluralism in the workplace and society in general, but also burdened with school debt, deteriorating job prospects, and downward mobility for the first time ever in America. They’re confused and questioning.

- Generation Z members — 67 million in number — were raised in a technological revolution and accepted it wholeheartedly. They were coddled by fawning parents and grandparents pushing them to succeed. They also saw the decline of the old dinosaur firms and the rise of the young disrupters — and have an entrepreneurial spirit that’s challenging everything. And while they celebrate economic wealth and accomplishment, they’ve also retained the social liberalism of the Millennials; they want their suppliers to be intentional in their values. But they’re overwhelmed, trying to do everything at once, and now beginning to question their work-life balance decisions.

Defining your good customers

A fresh look at customers should start with the ones you enjoy seeing — those who regularly purchase goods or services from you. But sometimes, knowing what a customer is not can be just as important as knowing what a customer is. You can find out about your business and best customers by observing the other kinds of customers shopping your industry — the difficult customers, the former customers, and the nonexistent customers.

Your business can measure and describe its customers in several ways:

- Track each customer’s unit and revenue volume over relevant time frames.

- Figure out who your customers are, including demographic and psychographic data that you have available or can access.

- Learn what and who influences your customers.

If you want more details on how to separate your customers into appropriate groups (market segments), check out Chapter 6.

Handling your not-so-best customers

“Can there be such a thing as a ‘bad’ customer? Isn’t that a contradiction?” you ask. Not at all. Bad customers — like the neighbor from hell — simply cause you more trouble than they’re worth and don’t fit into your company’s values and strategies. Let them pollute some other neighborhood, not yours. Bad customers do the following:

- Ask you to serve them in ways that aren’t practical or economic for your company.

- Distract you, causing you to veer away from your strategy and dilute your business plan.

- Purchase in such small quantities that the cost of doing business with them far outweighs any revenue that they generate.

- Require so much service and attention that you can’t focus your efforts on more valuable (and profitable) customers.

- Remain dissatisfied with what you do, despite all your best efforts.

You need to consider two things here: (a) how to identify the less-than-ideal customers, and (b) how to de-market them without giving yourself a black eye that could be embarrassing or worse. Start by closely examining your current book of business.

How you communicate the news to those you’ve cut off is critical, however. No one likes rejection. Be sure you manage the de-marketing plan with care and consideration, perhaps directing them to an alternative supplier.

1. First figure out who they are.

2a. Try to convert them into good customers if you can.

2b. If they can’t be prodded into increasing their purchase volume, then relegate them to a lower status by, for example, limiting their transactions with you to online-only or self-service.

2c. But if your best efforts still fail, wash your hands of them and move on.

Scoping out the other guy’s customers

You may think that when customers take their business elsewhere, it points to a failure on your part. On the contrary, these people present an opportunity. The fact that you haven’t been able to serve this group gives you a challenge: Finding out what your market really thinks is important. Your competitors’ customers tell you what you lack as a company. This information is extremely useful, especially when you work on the big picture in the early stages of business planning, defining who you are and who you want to serve.

- Spend some time where customers gather. Use trade shows, user groups, and industry conferences to make informal contacts and begin a dialogue with your non-customers. And don’t forget that customer comment pages of vendor websites often are chock-full of valuable insights straight from the horse’s mouth — both positive and negative.

- Ask pointed questions of people who choose competing products, perhaps through a focus group (a structured get-together of a curated group of consumers, led by an external facilitator who isn’t perceived as biased or judgmental).

- Did they investigate what was available on the market? Are they even aware of you? If so, what are their impressions? What turns them off?

Listen to what these consumers have to say, even if it’s painful. Don’t get defensive if you hear negative things about your firm or its goods and services. Information about your customers is valuable, if not priceless.

It’s like having a customer service representative or department in your own firm. By encouraging customers to comment, you learn things that otherwise you might find out only after sales slide and a paid consultant investigates and reports on free information available in real-time if only you had created an accessible channel. (And don’t call it the “Complaint Department.” No one wants to work there, and most customers are put off by the term. And think about it: A customer complaint is in fact a plea for help — it’s free consulting. Are you listening?)

Discovering the Ways Customers Behave

Perhaps the most difficult — and useful — questions that you can answer about your customers have to do with their behavior: Why do they buy what they buy? What actually compels them to seek out products or services in the marketplace? What are they really looking for? Unfortunately, most people don’t wear their hearts on their sleeves. They often conceal their true feelings, fearful they aren’t mainstream enough and might raise the ire of others. Who wants that?

Because of this, market research surveys and questionnaires that seemingly ask straightforward questions can’t always be trusted to reveal underlying attitudes and beliefs. You need to probe deeper to get at the rock-bottom truth about your customers before you can design-in the features they really seek and communicate to them in words and symbols they get. In the past you might have needed a psychiatrist to do this work for you, but not today. Modern technology has given us modern tools to do the excavation in an affordable way — kind of like a digital Dr. Phil.

Understanding customer needs

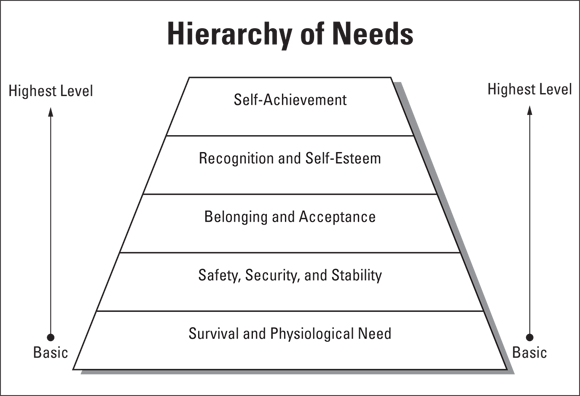

Why do people buy things in the first place? Psychologist types tell us that needs fulfillment is really at the heart of all consumer behavior (see Figure 7-1). Everybody has needs and wants. When a customer discovers a need, it creates the motivation that drives human activity:

- Survival, at the most basic level, results in the universal need for food, shelter, and clothing. In the modern world, these basic needs support grocery stores, carpenters, and the garment industry.

- The urge for safety, security, and stability generates the need for seat belts in cars, funds in a financial institution account, and all kinds of insurance products and even home alarm systems.

- The desire for belonging and acceptance creates the need for designer-label duds, members-only clubs, and beauty-enhancing aids.

- The urge to be recognized and held in esteem establishes the need for expensive private universities, ever bigger homes, and award plaques and trophies (the latter of various kinds).

- The desire for self-achievement results in the need for adventure vacations, quiz shows, and web-based educational courses.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 7-1: A basic overview of people’s needs, as sketched out some 50 years ago by the social psychologist Abraham Maslow in his famous “Hierarchy of Needs” model.

Consider an example of understanding customer needs: Ever notice those ads where a shapely young female is paraded out in a red bikini to show off the latest round of drills, hammers, and saws? Let’s be honest here, the idea of commoditizing a woman’s body in order to sell products is more than tacky. So those who wallow in this gutter are simply despicable oinkers? Perhaps. But why would otherwise upstanding firms indulge in such sexist behavior? Primarily because it works.

At the end of the day we humans are the top dogs in the animal kingdom, and like all creatures large and small, we have a powerful innate drive to procreate the species and outsmart the daily sources of destruction — survival of the fittest as Dr. Darwin said. The DIY tool-buying segment tends to be overwhelmingly male, and many are in their prime child-rearing years. They’re the target for brands like DeWalt and Craftsman found in Home Depot and Sears. But to get their attention amidst the barrage of shrieking advertising messages that bombard us almost everywhere we turn, something more alluring than a picture of a screwdriver is needed. Enter the hot model in the bikini. Psychology 101 — you figure out what primal instincts are aroused.

But why red? Because we humanoids respond visually to red and yellow more than other colors; they have the longest wavelengths on the visible spectrum. And if you can’t attract and engage the buyer in the first place, you won’t be able to sell them your product, be it computer games or garage tools.

Determining customer motives

Motives are needs that have been awakened and activated (refer to Figure 7-1). They send people scurrying into the marketplace to search for products or services that can fulfill a particular need, although they aren’t always what they seem to be:

- Greeting-card companies, for example, don’t charge exorbitant prices just to sell cute little jingles (either online or in print). The prices are justified because they actually sell small insurance policies against their customers’ fear of feeling guilty. And perhaps that fear of guilt (over a missed birthday or anniversary) is really what propels buyers into the greeting-card market.

- Most people have a need to be accepted and liked by others, and they enjoy having a certain amount of status in the eyes of others. This powerful motivation creates great market opportunities for beauty shops, aerobics studios, luxury goods, and breath-mint companies.

Although motives obviously apply to individual consumers, they work equally well in the context of business or corporate behavior. When a business sends out a post to employees or brings in a facilitator to explain to the troops why diversity in the workplace is good and gender or other forms of discrimination are bad, what’s the motivation? We hope it’s because organizational leadership believes that this message is important and should be heard and understood by everyone at the firm. But there might be another motivation. If for some reason an employee believes they were the victim of such reprehensible behavior by a supervisor or colleague, the firm can claim that it did what was legally necessary to inform staff that this behavior was definitely unacceptable at the firm and contrary to policy. If there was, in fact, a breach of the law, then it was the fault of the involved individuals, so sue them; the firm itself should not be held liable. What was the real motivation for the firm’s nondiscrimination policies and training? You be the judge.

Figuring Out How Customers Make Choices

How do customers make choices in the marketplace? The most important thing to remember is that customers decide to buy things based on their view of the world — their perceptions of reality. Few customers buy without thinking; instead, they bring their perceptions of the world into a decision-making process that (ideally) leads them to purchase your product or service rather than your competitors’. (Remember our definition of a customer? Someone who doesn’t have a better alternative.)

Realizing perceptions are reality

Customer perceptions represent the market’s worldview and include not only what your customers think of your products and services, but also how they see your company and view your competitors.

As customers turn to the marketplace, they confront a mind-boggling array of choices. Many variables influence your customers as they evaluate their alternatives: advertising, endorsements, reviews, and salesmanship, not to mention their own gut reactions. It’s been estimated that a typical urban or suburban American is exposed to between 4,000 and 10,000 advertising messages per day. Shopper paradise, or Dante’s inferno? You need to know how customers respond to all these stimuli if you ultimately want to earn and keep their business.

Have you ever wondered, for example, why men’s yellow sweaters are difficult to find or why women’s clothes in black are everywhere? Well, it’s not because your eyesight is failing: Market research consistently shows that a majority of men believe that the color yellow suggests weakness, and most women think black makes them look thin. Unfortunately, body shaming thrives in America.

Setting in motion the five steps to adoption

The decision-making process (DMP) that buyers go through often involves a series of well-defined steps leading up to the adoption of a product or service. (In this case, of course, adoption refers to a newly formed relationship with that product or service — not a child or a pet. But we’re all for that, too, if it’s your desire.)

TABLE 7-1 The Buyer’s Five-Step Adoption Process

Primary Steps | Description of Customer | Your Task |

|---|---|---|

Awareness | Aware of a product or service but lacking detailed knowledge | Develop a strategy that educates and excites potential customers |

Interest | Curious because of publicity and seeking more information | Provide more detailed product information and continue to build momentum |

Evaluation | Deciding whether or not to test the product or service | Make the product-evaluation process as easy and rewarding as possible |

Trial | Using the product or service on a test basis | Make the trial as simple and risk-free as you can |

Adoption | Deciding to become a regular user | Develop strategies to retain good customers |

Suppose that you own a software company with a brand-new business-productivity program or app. You fear, however, that customers will be reluctant to give the program a try, if they assume the software is difficult to figure out or incompatible with their computer systems. (Keep in mind that people act on their perceptions of reality rather than on the reality itself!) To move potential customers past the evaluation step of the adoption process, your CTA (“call to action” on your website) may want to consider access to a trial version of the program (“Click here for a trial!”) — along with a simple purchase option after the trial period ends. Microsoft’s Office 365 offers this, as do thousands of others like the movie streaming site Hulu or digital music app Spotify. Some software makers have gone even further by sponsoring hands-on workshops to demonstrate their hopefully cool new programs, which gives potential buyers a chance to evaluate, try out, and get comfortable with the product — all before they buy it.

Understanding the Global Customer

Powerful political forces began to converge in the ending decades of the 20th century to create conditions that opened up economic borders around the world. By the start of the 21st century, it was estimated that more than 3 billion new global citizens could participate in the grand dance of the capitalist market. The more adventurous large Western firms quickly grasped the opportunities for growth and made plans to push through the opening gates. At first the stampede was especially focused on the “BRICs” — that is, Brazil, Russia, India, and China, which between them held more than 2 billion people.

The hope, of course, was that the ways and habits of the so-called “advanced economies” would quickly take root in these newly “emerging economies.” Unfortunately, the business pioneers had to learn a hard lesson before dreams of wealth actually materialized. This had to do with culture, both national and local: Not all customers throughout the world behaved alike. In fact, some of them were absolutely contrary to how the good folks back home shopped and bought. Read the nearby sidebar “The moral of the story: Know thy customer” before you disagree.

As this fact sank in, companies brought in the Indiana Jones types to get a better handle on how their products and services could be reshaped to meet international demands. Culture, we are told, does have similar foundations the world over. It seems that people, no matter where they live — the heavily populated places or the far-off Timbuktus (even Timbukthrees) — all have basic systems for the following: economic exchange, family formation, education, social norm and justice enforcement, and spiritual beliefs. But surely the forces of globalization, especially mass communication, would bring about a convergence of these cultural variables so that the global bazaar would be a one-size-fits-all paradise for the big firms moving in, right?

So was globalization just a giant chase for fool’s gold, to be shunned like the plague by the savvy business planner? No again. Not everyone benefitted from this trend, which was more evident in the advanced economies. And some products do appear to be universal in their appeal; who doesn’t love Mickey Mouse, and a Big Mac and fries seem to whet the appetite worldwide. Overall we’re fans of globalization, and we think you should be as well. If nothing else, population trends favor emerging market nations; these are the growth hot spots both today and in the future that will drive revenue, maybe for your firm, too.

More importantly, the opening of borders demonstrates that there’s a lot of commonality in all the peoples of the world and that we really can find bonds of agreement when we get to know one another better. This is good — very good, in fact — when held up to the many atrocities of the past century. When approached carefully and conscientiously, the opportunities in foreign markets can be positive for all, real win-win situations. And this goes for the small and medium-sized enterprises as well as the big elephants that trek the commercial jungle. So when you’re evaluating how to boost sales, don’t neglect these international markets, even though they talk in many tongues and use currencies that might be only dimes to the dollar. Serious opportunity is out there if you’re willing to make the effort to know how these global customers think and choose their suppliers.

Serving Your Customers Better

The more you discover about your customers, the better you can serve them. And in competitive markets, that can mean the difference between a successful business and a failure. Remember, your competitors can always try to copy the products you offer, and they will, but copying the services you provide to support those products is a lot more difficult.

Often, the difference between a customer and a satisfied customer is based entirely on the service you provide. Satisfied customers become loyal customers. And loyal customers are one of the keys to growth and profit.

Take a look at the flip side of the coin: Lost customers are expensive. Research shows that most of your customers probably aren’t profitable until they’ve been with you for several years. Why? Because in the beginning, you have to shoulder hidden costs, such as advertising, promotions, sales commissions, customer training, and what the bean counters call “SG&A” expenses. SG&A is sales, general, and administrative costs (also called “overhead,” but be wary, or it can put you under water). Your firm likely needs to spend a fair amount of money just to open the door each morning, and it’s difficult to accurately allocate these general costs to an individual product or service. To stay competitive, you will likely price your new offering based on the direct costs necessary to bring it to market and add in a fair profit margin for everything else.

OK, but what happens? If you did have a truly accurate cost allocation system, you’d likely find that your margin isn’t covering all those “new customer acquisition” costs. In fact, as the research showed, that new customer was actually unprofitable for those first few years they purchased from you. It took time to pay off those initial acquisition costs. And worse: The same studies showed that a typical company loses 15 to 20 percent of its customer base annually. Many of these customers were long-timers — that is, their prior purchases had covered that hidden acquisition cost. Meanwhile, you’re flogging the sales team to get out there and corral new customers to make up for the loss and meet the annual growth goals.

But what kind of customers come in? New ones, of course. Expensive ones. Customers who have yet to pay off their “acquisition” costs. And who left? To a large extent, customers who have already paid for themselves — the profitable ones. Studies across industries indicate that it costs about five times as much to attract a new customer as it does to keep an existing one. And it can cost up to 16 times as much to bring a new customer up to the level of profitability that a loyal customer represents.

- The inflection of a customer service rep’s voice can be off-putting to a customer, as it may sound hostile. One way to overcome that? One firm put mirrors on the wall facing its call-center workers, with a big sign over it: KEEP SMILING! Seems that when you smile, your voice turns down, and you sound more friendly to the caller.

- Another tactic is to use what’s called “concreteness” in language. When an unhappy customer calls to ask what to do now that a flight’s been cancelled, a typical response might be “Let me see what we can do.” But a better one? “Let’s see what might be available on a Chicago to Dallas connection going out this afternoon.” This conveys an assurance to the customer that you have heard what they said and you are on it, pronto.

Looking at a Special Case: Business Customers

Many of the business examples we include in this book have to do with companies that sell products and services primarily to individual consumers. That’s understandable, as they get a lot more attention by everybody and they are more interesting to discuss (we mean, can we talk industrial fasteners here?). But we don’t want to neglect the other companies out there in the business-to-business or B2B markets, especially since there’s more commerce done in this segment than in B2C markets. (Industrial fasteners actually account for about $90 billion in annual worldwide sales these days; got your attention now?)

There’s another characteristic of industrial markets that also makes them highly competitive: Many products and services are commodities (see Chapter 5). Since individual incumbents in a particular industry offer very similar products, how can you compete on anything other than price? Throw in the tsunami of goods flowing across borders from abroad, where differing levels of economic development often mean lower costs for foreign suppliers, and the hurdle is raised even further for domestic suppliers in wealthy countries like the United States.

In this section, you find details on how companies, institutions, and government agencies behave when they act as the customers. What makes the business buyer different? Read on to find out.

Filling secondhand demand

Demand for goods and services in B2B markets is almost always derived demand. In other words, businesses purchase only the goods and services that they can use to better serve their own customers.

Steel is typically a product that most all individual consumers buy — but never shop for. Own a home or a car, have some appliances in the kitchen or tools in the garage? You have steel. But what you shopped for and then actually bought was a product containing the metal. Same goes for microprocessors: They’re everywhere around you today — your phone, PC or laptop, in the car and other electronic devices. But your purchase of a semiconductor chip was an indirect one.

What are the implications for these derived demand product firms? If a steel maker cuts price across the board, for example, should it expect a huge increase in orders? Not necessarily. Steel users increase their purchases only if they think that they can sell more of their own product or service, and sales may be affected by many factors beyond the underlying price of steel. How many of us dashed out to buy a new Chrysler Jeep the last time US Steel (USX Corporation) reduced its steel prices by 10 percent?

- Will a price reduction on your part result in increased sales for your business customers — and your company?

- Will your customers (and their customers) benefit if you offer them additional product features that raise costs but don’t add much value?

- Are your business customers looking for continuity and price stability so they can do adequate advance planning at their end?

Steel, as we note, is a classic commodity product. US Steel operated the nation’s largest steel mill in Gary, Indiana, near many of its industrial customers. But these users had other choices available to them, so price was critical, and profit margins were always squeezed. The mill’s general manager decided to try a different tactic: He instituted a new customer service policy. After an order was received and a delivery date set, then that’s when the order would be sent. The order would be fulfilled on time, in full, every time. If it wasn’t? The mill would pay a penalty to the customer. This proved to be a benefit that customers were willing to pay for, since their own production schedules and operations were highly dependent on having the steel order there precisely when needed. Higher sales were booked; more steel was rolled; capacity utilization went up (the key metric in a mill’s efficiency); and profits rose dramatically. The savvy general manager was promoted to HQ in Pittsburgh to oversee all steel operations for the firm (perhaps they read an early edition of this book).

Decision-making as a formal affair

Purchase decisions in the business-to-business marketplace tend to be more formal, rational, and professional than in most consumer markets. Many people from different parts of the target company may be involved in the decision-making process (DMP). One division in the company may recommend your product or service, another may acquire it, yet another may pay for it, and all the divisions do the work for a separate customer center that actually uses the product. Taken together, these groups form the decision-making unit (DMU).

Table 7-2 describes three ways in which a business DMU may behave when it thinks about buying a product or service. Businesses often change their buying behavior over time, so knowing where your business customers are in their DMP can help you plan when and how to make the sale.

TABLE 7-2 How Businesses Behave When They Buy

Buying Behavior | Description of the Customer’s DMP |

|---|---|

Business as usual | Continues to order more of the product or service, automating the process via EDI (electronic data interchange) software that communicates with suppliers to ensure that inventories don’t fall below certain levels. |

Yes, but … | Asks for changes in the existing sales arrangement, modifying one or more purchase terms (such as pricing, financing, quantities, and options), and including various people who are part of the DMU. |

Opportunity knocks | Purchases a product or service for the first time, perhaps after putting out a request for proposal (RFP) to several possible suppliers and making a deliberate, complete decision involving all parties in the DMU. |

Knowing the forces to be reckoned with

As you work with business customers, you have to deal with several powerful forces that you rarely encounter in consumer markets. It’s usually a waste to create a “warm and fuzzy” ad campaign that plays on the emotions of the buyers to persuade them to bite. If you want your B2B strategies to succeed over time, you must factor these forces into your business plans.

Asking some important questions

Consider the following questions (and there are many more that might apply to your industry):

- What’s the state of your customer’s business?

- Is your customer’s business booming, maturing, or dying?

- Is it facing increased competition or enjoying record sales and profits?

- Is it shedding assets, outsourcing operations, and restructuring?

- Is it threatening to become a competitor to you?

- How does your customer’s company manage its supply chain management operations?

- Does your customer purchase from you centrally, or does it have buyers scattered around the company?

- Does the purchase require several levels of approval before your customer makes a decision?

- Do senior executives (who may or may not know much about product details) make the ultimate purchase decisions?

- Does your customer use an online bidding system for RFPs (request for proposals)?

- Who’s important to whom?

- Do your customer’s key decision-makers tend to be engineers, finance, or marketing staff?

- Does your customer use both small and large suppliers? Does it seek diversity in its suppliers?

- Does your customer have a policy of requiring more than one supplier in critical areas?

- Does your customer appear to have a long-term relationship with existing suppliers? Does it use suppliers also used by industry leaders, or does it use mavericks?

Investigating unique forces

- Get out into the field and talk to potential business buyers. Phone calls, letters, and online or other communication modes are efficient, but nothing beats the effectiveness of a face-to-face meeting that allows for relationship personalization.

- Attend conferences and conventions that your business customers attend, and find out about critical events and forces that shape their thinking. Maybe even sponsor a meet-and-greet there.

You also might investigate a supplier of tools to enhance your digital marketing efforts. Many fine vendors are in this space today, and they’re not just for the big guys. For example, Adobe Systems, the Silicon Valley firm you probably know best from its pioneering PDF (Portable Document Format) product, set up Adobe Marketing Cloud in 2012. Adobe provides a comprehensive and integrated set of digital marketing solutions to its customers and partners. Even though it counts a good number of Fortune 500 firms as customers, it also has something for small and medium-sized enterprises. These solutions focus on analytics, web and app experience management, testing and targeting, advertising, audience management, video, social engagement, and campaign orchestration — all on a single platform. This allows you to get a deep insight into your customers and then build personalized campaigns to manage the relationships. Adobe is not the only one out there offering these services, but it’s a good example of how you can get some help until you’re able to build your own in-house digital capabilities.

If you think about your business only in terms of your existing customers and current products, you risk losing sight of broader customer needs — needs that a competitor is no doubt going to satisfy at some point if you don’t. You also create a shortsighted view of your strategic choices that can result in missed market opportunities and woefully inadequate business plans.

If you think about your business only in terms of your existing customers and current products, you risk losing sight of broader customer needs — needs that a competitor is no doubt going to satisfy at some point if you don’t. You also create a shortsighted view of your strategic choices that can result in missed market opportunities and woefully inadequate business plans. Do you want to know our favorite definition of a “customer”? Someone who doesn’t have a better alternative. If you aren’t the best alternative, you’re toast.

Do you want to know our favorite definition of a “customer”? Someone who doesn’t have a better alternative. If you aren’t the best alternative, you’re toast. Serve the steak … but sell the sizzle. Successful restaurants learned long ago that patrons wanted more than delicious and healthy edibles. That was a given, what you needed to compete. But with so many dining choices out there, you had to satisfy more than an empty stomach with good-tasting food. The smarter players realized that an appeal to the customer’s other sensory perceptions could be a way to go. This included not only visual appeal — who wants to eat in a dump? — but also audio and olfactory receptors, like soothing background music and mouth-watering smells. Let ’em hear the sizzle of the pan, smell the savory sauce. You win when you understand your customers in all their dimensions, not just the one directly tied to your product or service. Mmmm, hand us that menu now.

Serve the steak … but sell the sizzle. Successful restaurants learned long ago that patrons wanted more than delicious and healthy edibles. That was a given, what you needed to compete. But with so many dining choices out there, you had to satisfy more than an empty stomach with good-tasting food. The smarter players realized that an appeal to the customer’s other sensory perceptions could be a way to go. This included not only visual appeal — who wants to eat in a dump? — but also audio and olfactory receptors, like soothing background music and mouth-watering smells. Let ’em hear the sizzle of the pan, smell the savory sauce. You win when you understand your customers in all their dimensions, not just the one directly tied to your product or service. Mmmm, hand us that menu now.