Chapter 5

Examining the Business Environment

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Defining the business that you’re in

Defining the business that you’re in

![]() Taking a closer look at your industry

Taking a closer look at your industry

![]() Finding out where to turn for information

Finding out where to turn for information

![]() Knowing the keys to success

Knowing the keys to success

![]() Watching out for business opportunities and threats

Watching out for business opportunities and threats

One of the most important questions you can ask yourself as you prepare to create a business plan is “What business am I really in?” The question may sound simple, even trivial, which is precisely the reason why businesspeople too often ignore it. However, if you can answer this basic question correctly, you take the first giant step toward creating an effective business plan.

Remember when crisscrossing the United States on trains, with their elegant dining cars, two-level Pullman cars, and smoking lounges, was commonplace? Probably not. But you can still catch an old movie and become a bit nostalgic for a long-lost era (except for that smoking part). Railroad companies in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s thought that they knew exactly what business they were in: the railroad business, duh. The question was a no-brainer. As it turned out, however, passengers thought in more general terms: effective and efficient transportation. Railroad companies soon found competition in the form of interstate highways, General Motors and the Ford Motor Company, American Airlines, and airports. The forces that drove the choo-choo business extended well beyond rails. The railroad companies didn’t see the big picture — one business guru cleverly termed their problem “marketing myopia” — and they never regained their former glory.

The market, like the house in Las Vegas (or for that matter Atlantic City, Macao, or Monte Carlo), always wins. Always. So defog those glasses. In this chapter, we show you how to begin a systematic analysis of just how your market and chosen industry works. We analyze your industry, search for critical success factors, and then give you some pointers on preparing for the opportunities and threats that loom on the horizon. You’re not going to be able to predict the future, but we bet you’ll be much better prepared to deal with your hand no matter how the cards play out.

Understanding Your Business

- What basic needs do you fulfill?

- What underlying forces are at work?

- What role does your company play?

We say more about the shortsightedness of leadership in Chapter 17 and frame some ways to prevent you from falling into similar traps. First, though, we want to make sure that your company isn’t like the railroads by understanding the underlying forces that shape your business environment. Start by analyzing your industry. (For a closer look at your customers, check out Chapters 6 and 7. The competition gets the once-over in Chapter 8. And — just love those new specs — we have you take a closer look at your company in Chapters 9 and 10.)

Analyzing Your Industry

No business operates alone. No matter what kind of business you’re in, you’re affected by forces around you that you must recognize, plan for, and deal with to be successful over the long haul. Ivory-tower types often call this process industry analysis. You may have the urge to run the other way when the word analysis pops up (or perhaps think about your mother). We don’t want to sugarcoat this step, but we try to make the process as painless as possible.

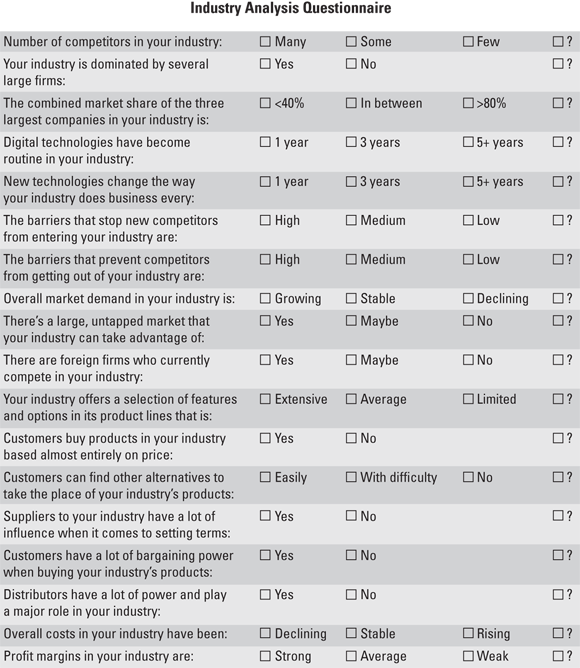

How much do you already know? Take a moment to complete the Industry Analysis Questionnaire (see Figure 5-1). If you’re unsure about an answer, check the ? box.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-1: The Industry Analysis Questionnaire.

Your answers provide a snapshot of what you think you know. The question boxes that you check highlight the areas that need a closer look. In any case, now you can roll up your sleeves and take a serious poke at completing your industry analysis.

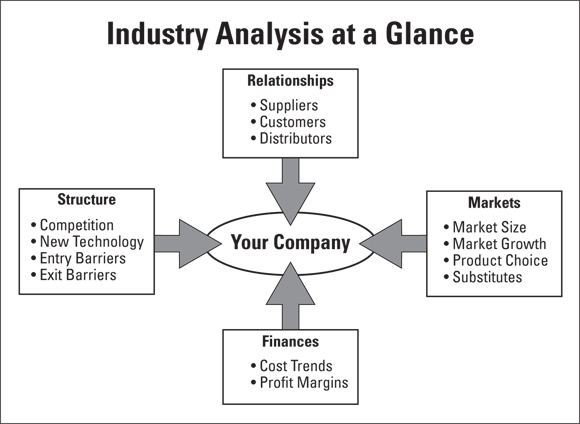

The good news is that many smart people have already worked hard at analyzing all sorts of industries. Although no two businesses are exactly the same, basic forces seem to be at work across many industries (see Figure 5-2).

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-2: The four major components of analyzing an industry.

The following sections describe the most important of these forces — those factors in your industry — and provide some hints on how you can think about these forces in terms of your business planning.

Configuring the structure

Every industry, from auto manufacturers to zucchini farmers and everything in between, has a unique shape and structure. Here are a few tips on how to recognize the particular structure of your industry.

Taking stock of your rivals

The number of competitors, taken by itself, has a major impact on the shape of an industry. This is referred to as industry structure. An industry can be a monopoly (one monster company with no significant competitors), an oligopoly (a small number of strong competitors who collectively dominate), a monopsony (many competitors but only one buyer), or a polyopoly (many viable competitors with no one overly dominant). This last term is rarely invoked, but we figure that you could use a word to represent the vast majority of industries out there, probably yours as well (and besides, it’ll make you look that much smarter to your colleagues, who are admiring how well you create your business plan). In addition to the number of competitors, you should check out how many of the companies are big and how many are small, as well as how they carve up the various markets that they compete in.

Examining technology

Changing technology drives many industries. Just consider digital to start with. Look both at how much and how fast things change in your own business. Although you don’t need to become a rocket scientist, you should feel comfortable with the underlying technological issues that fuel the change around you. You should also find out who owns or controls the technologies, especially IT, and how easily you can obtain them in a legal and ethical manner.

Overcoming barriers

The “table fees” that make it more or less difficult for new competitors to join the game are referred to as entry barriers. Some of these barriers are obvious — high capital costs (a lot of money needed up front), for example, to build economies of scale. In this case, the bigger you are, the lower your costs and, thus, more attractive to customers — all of which can discourage brand-new competitors by pricing them out. Other barriers are easy to miss, such as complex distribution systems that make it hard to reach customers without going through expensive gatekeepers. Try writing the Great New American Novel and getting it turned into a real book easily available to readers, without having to go through agents and their contacts (but wait, isn’t Amazon …?). Strong customer loyalty, long-term contracts, or a buyer’s costs associated with switching suppliers can also create formidable barriers for the new kids on the block.

As you think about your business, list the entry barriers that you think stand in the way of new competitors: for example, deeply entrenched incumbents in the industry, capital costs, distribution, access to raw materials, new technology, scale economies, regulation, patents, and switching costs. (Whew! Still with us?) Rank these barriers based on how impenetrable you find them. On which side of each barrier do you stand? Be realistic, but keep in mind that there were many obstacles that entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, and Jeff Bezos also encountered and overcame. Finish this book, and maybe you can, too!

Cashing out

Sometimes it can be hard to leave a casino, even when you really want to. How difficult is it for companies in an industry to get out of the market if they want to? The ties and attachments that keep competitors around are called exit barriers. Exit barriers can include everything from expensive factories or specialized equipment that companies can’t easily unload, to labor contracts with unfunded pension obligations for terminated workers, extended customer leases, service agreements, and government regulations. The problem is that firms with high exit barriers often do anything to stay alive, even if that means cutting prices and, thus, decreasing profit margins for everyone else — including potential new entrants.

Find out how many companies have left your industry over the past five years or so. Try to figure out why they got out of the market and what sort of difficulties they ran into as they made their way to the exits. How many of them left voluntarily, and how many were shown the door, penniless and in tatters? Spend some time scrolling through the pages of business blogs, magazines, and journals — they offer plenty of useful insights.

Measuring the markets

Competition comes down to customers, and customers make up markets. Ideally, the customers you intend to target represent a market that you feel is ripe for new goods or services. Some call this your addressable market. The following tips help you judge for yourself.

Just how big is big?

The size of a market tells you a lot about what’s likely to happen to it over time, especially when it comes to competition. Large markets, for example, are always big news and can’t help but attract the attention of strong competitors. Smaller markets don’t get the same spotlight, however, and because competitors can easily overlook them, they often represent business opportunities for the little guy — giving you lead time to get up and running before someone’s radar spots you. You hit the real jackpot if you can turn a small market into a bigger market by discovering a usage gap — finding a new use for your product or service that no other company has thought of before.

Make some market projections based on the new uses that you’re thinking about. You might also want to check out Chapter 15, where we explain the “product life cycle” concept and how demand shifts over time as market penetration evolves.

Growing or shrinking?

If large markets are good news, rapidly growing markets are great news, and competitors are going to circle like buzzards after the kill. A growing market offers the best odds for new players to gain a foothold and successfully join the existing competition. As for shrinking markets, you can bet that the old lions guarding the den will become leaner, meaner, and fiercer. (BTW, why would you want to chase declining demand?) As markets change size in either direction, the intensity of competition is likely to heat up.

Identify changes in the size of your market over the past three to five years, in terms of both units sold and revenue generated. If the market is changing rapidly in either direction, look for opportunities and try to predict the likely effect on both the numbers and the intensity of the competition. The Internet and other sources of business news are good places to start gathering data. Also try talking to customers, suppliers, and even other competitors in the market.

What choices do customers have?

A quick survey of the similarities and differences among products or services in a market measures something called product differentiation. If each product looks pretty much like every other product (think sugar or drywall), you can bet that price is important to customers in what’s known as a commodities marketplace. On the other hand, if each product is different and offers customers something unique or special — from credit card terms and benefits to RVs — product features are likely to determine long-term success or failure in the market.

Take a hard look at the products or services that the top three competitors in your market offer. How similar are they? In what ways are they unique? Think about what you can do to differentiate your product — adding special features or offering value-added services — so you can compete in ways beyond simply raising or lowering your price. If price is your only differentiator, it’s often a race to the bottom — any fool can come along and slide in under you, forcing you to match or walk.

Today you can “showroom” or “webroom” just about any product to obtain valuable competitor information:

- Showrooming means going into a physical store, using your smartphone to snap a picture of a product’s ID or other details on the label, and then Googling this to see what comes up. Online retailers typically will show competing products (“maybe you will like these instead!”).

- Webrooming is the opposite: first capturing the product details from the web and then marching off to the store to see what it’s like in its physical rather than virtual configuration.

What about something altogether different?

Every once in a while, a completely new type of product or service suddenly makes a debut in a market, crashing the party so to speak. The product often comes out of another industry and may even be based on a different technology. The new product becomes an overnight rival for the affections of existing customers — the rise of email to challenge fax machines, for example, or the proliferation of digital cameras to overtake film-based versions, or the social media platform TikTok offering users an easy means to post 30-second videos on their site. The threat of product substitution — new products taking over existing ones — is real, especially in fast-changing, highly competitive markets that are vulnerable to disruption, and what market isn’t today?

If you’re on the receiving end of substitution effects, you’ll want to consider how to hang on to those customers you already have. What barriers can you erect to keep them loyal? What new benefits might you offer? Look at what the legacy airline firms did when cheap low-frill competitors flew in: They came up with frequent flyer programs, with nontransferable miles, to raise the cost of switching airlines.

Think about what your customers did 5, 10, or maybe even 20 years ago (if you’re a tad bit on the gray side of life). Did they use your product or a similar one back then, or did a completely different kind of service or product serve their needs? Think about sitting in a stuffy classroom taking notes — and then Zooming in on your laptop while sitting at home for an online educational experience. What about 1, 5, or 10 years from now? What types of products or services may satisfy your customers’ needs then? How, for example, might artificial intelligence (AI) or augmented reality influence your business or market? Put on that thinking cap and let ’er rip; although you can’t predict the future, you can envision possibilities.

Remembering the relationships

Business, like the Internet, is all about connections. Connections aren’t just a matter of who you know — they involve who supplies your raw materials, distributes your product, and touts your services. Connections are about who your customers are and what kind of relationship you have with them. Social media influencers have realized this for years now, with the savvier ones bulking up their bank accounts as a result. A few tips can help you spot the key connections on which your business depends.

Recognizing supply and demand

One obvious way to think about products and services is how a company puts them together. Every company relies on outside suppliers at some stage of the assembly process, whether for basic supplies and raw materials or for entire finished components of the product itself. This applies even to such industries as online punditry. That brilliant gal whose newsletter you subscribe to seems to know everything going on in your industry. Is she really that omniscient, or does she have a really deep network of sources that keeps her up to date? When outside suppliers enter the picture, the nature of what they supply — the availability, complexity, and importance of that product or service to the company — often determines how much control they have over the terms of their relationship with a company. That means everything from prices and credit terms to delivery schedules.

The recent COVID-19 global pandemic made many firms acutely aware of their dependence on good supply chain management policies and procedures. The crisis shuttered factories and stopped output the world over. Lacking a component for installation at the assembly line meant that product couldn’t be shipped. And for the final retailer, an unshipped product is one that’s out of stock on the shelf — that is, a lost sale when the customer called.

It should be no surprise that many firms today are rethinking how they can build resiliency into their supply chains to overcome these potential bottleneck problems. Think about your own suppliers, be they insiders with intimate knowledge of industry events or providers of key components necessary for production. Are any of them in a position to limit your access or to raise prices on you? Might one suddenly disappear, and if so, can you turn to alternative sources? Can you form alliances with key suppliers or enter into long-term contracts that turn transactions into relationships? Are any of your suppliers capable of doing what you do, perhaps transforming themselves into competitors? How can you protect yourself?

Keeping customers happy

You’ve probably heard the expression “It’s a buyers’ market.” As an industry becomes more competitive, the balance of power naturally tends to shift toward the customer. Because they have a growing number of products to choose among, customers can afford to be finicky. As they shop around, customers make demands that often pressure businesses to lower prices, expand service, and develop new product features. A few large customers have even greater leverage as they negotiate favorable terms.

The last time that you or your competitors adjusted prices, did you raise or lower them? If you lowered prices, competitive pressures no doubt are going to force you to lower them again at some point, especially if you’re in one of those commodity-type markets. Think about other ways in which you can compete. Perhaps you can upgrade your customer-service policies, offering an on-time/every-time/in-full guarantee for delivery of orders. If you raised prices, how much resistance did you encounter? Given higher prices, did you inadvertently tempt customers to do what you do for themselves, eliminating the need for your product or service altogether?

Delivering the sale

No matter how excited customers get about a product or service, they can’t buy it unless they can find it on the Internet, in a store, through a catalog, or at their front doors. Distribution systems see to it that products get to the customers. A distribution channel refers to the particular path that a product takes — including wholesalers and anyone else in the middle — before it arrives in the hands of the final customer. The longer the supply chain, the more power the channel has when it comes to controlling prices and terms. But those chains are now being twisted tighter and tighter, into much shorter lengths.

Collapsing the channel was made possible by the digital revolution. The companies at the end of the chain have the greatest control because they have direct access to the customer and the data associated with that person: contact information, specific product preferences, and a slew of ancillary knowledge that can be used for more accurate and cost-efficient marketing (see Chapter 6 for more on this). Think about what alternatives you have in distributing your product or service. What distribution channels seem to be most effective? Who has the power in these channels, and how is that power likely to shift? The D2C route — direct to consumer — has become not only popular with customers but also more profitable for the suppliers, because the midpoint handlers are eliminated and the supplier itself now owns customer data.

Try to think of some ways to snuggle up close to your customers so nothing will be lost in translation and the cost savings that come from eliminating the intermediate stops can be passed on as your gift to them. Don’t abuse the knowledge that your newly minted customer data provides you. It’s just not right. But when used conscientiously and skillfully, chances are that most customers will be thrilled.

Figuring out the finances

Successful business planning depends on you making sense of dollars-and-cents issues. What are the costs of doing business? What is the potential for profit? Understanding cost and profit behavior is fundamental to knowing how to compete in your industry. The following tips can help get you started.

The cost side

With a little effort, you can break down the overall cost of doing business into the various stages of producing a product or service, from raw material and fabrication costs to product assembly, distribution, marketing, and post-sale service expenses. This cost profile often is quite similar for companies competing in the same industry. You can get a handle on how one firm gains a cost advantage by identifying where the bulk of the costs occur in the business and then looking at ways to reduce those costs.

Economies of scale usually come into play when major costs are fixed up front (think of large manufacturing plants or expensive machinery, for example). Increasing the number of products sold automatically reduces the individual cost of each unit, because you don’t need to purchase a new machine each time you turn out a new product — that machine’s cost is spread out over more and more products. Experience curves or learning curves refer to the potential for lower costs that result from the repetition of methods during the production process. The more you do, the more experienced and knowledgeable you become and the faster you get — that is, learning by doing.

Size matters in these kinds of industries, as the race often goes to the swiftest — that is, the firm that can get big before others and, thus, more efficient in its use of fixed cost inputs. This provides it a distinct competitive advantage and, in fact, is one major reason that anti-monopoly laws were put in place.

The profit drivers

Companies typically have their own rules of thumb when it comes to expected profit margins — how much money they expect to end up with after they subtract all the costs, divided by all the money that they expect to take in. In certain industries, these profit margins remain fairly constant year after year, as demand is more or less predictable. Consider a local power generating utility: Demand for electricity is a function of the number of households and businesses in the region, and the numbers of these typically go up or down in slow patterns of movement. A look at the history of other industries, however, points to more volatile profitability. These cycles often reflect highly fluctuating demand, such as the market for luxury goods like fine jewelry or high-end sports cars. Profit will depend on how much of a product or service an industry sells and delivers compared to the cost and available capacity of production that’s been built up. You want to be able to predict demand as accurately as possible. (See Chapter 10 about profits and costs and how to get more of one and less of the other.)

Knowing where an industry stands along the cycles of consumer demand and cost, as well as the direction in which the industry is heading, tells you a lot about the competitive pressures that may lie ahead. Ideally, you want to find yourself in an industry with predictable demand and without much excess capacity — now or in the near future. Try to answer the following questions:

- Is your industry one that has well-known business cycles?

- Traditionally, how long are the business cycles?

- If you’ve been in business for a while, have your profit margins changed significantly in recent years?

- What direction do profits appear to be heading in?

- Do you think that these changes in profitability may affect the number of competitors you face or the intensity of the competition over the next one to three years?

Don’t stop with our list here. No doubt we’ve missed some industry forces that may be important and perhaps unique to your business situation. Are labor costs spiraling upward due to a spike in demand and a shortage of qualified workers? Spend a little extra time and creative effort on coming up with other forces as you work on your own industry analysis.

After you give some thought to the many forces at work in your industry, put together a word portrait of your industry — you probably know a lot more than you imagine about what’s going on but have never systematically put it down in writing.

Coming up with supporting data

In most cases you’ll likely need current data to support your take on how various industry forces shape your business environment. You may find it difficult, however, to get your hands on the right pieces of information to explain what makes your industry tick.

Sometimes you may come up empty-handed because your business proposition is so new that no one has collected the data you need, or perhaps companies aren’t willing to part with it because they don’t want outsiders (including potential competitors like you) to analyze the industry too carefully.

Most of the time, however, too much data is available, and the problem becomes knowing where to turn first for the information you need, so you don’t have to invest a ton of effort separating wheat from chaff. Here are some details on how to shuck useful information about your industry without becoming overwhelmed.

- Resources on the web: The first place to start for most industry sleuthing is the Internet. Just key in the name of your industry, press Enter, and see what happens. The more specific your wording, the closer you’ll get to what you need. Many searches will lead you to sites that collect data for a wide variety of businesses, allowing for a more detailed hunt. Just a couple of the many out there:

www.statista.comandwww.numerator.comare market research firms that track and report on many organizations. Most of these sources provide some free data but will want to charge for a deeper dive. For the latter, be sure you exhaust the gratis sites before taking the plunge. - Online data providers: A growing number of companies specialize in providing proprietary business- and industry-related data at your fingertips. Standard & Poor’s Industry Surveys (

www.loc.gov/rr/business//company/industry_surveys.html), D&B Hoovers (www.hoovers.com), and Dun & Bradstreet Reports (www.dnb.com) are all available on the Internet. The information usually isn’t free, but it may be worth the investment. To cut the cost, look for first-time user offers or special promotions. - Government sources: Government agencies at all levels provide a wealth of data free for the asking, and you can find a good deal of it on the Internet. At the Federal level, check out the Securities & Exchange Commission (

www.sec.gov), the Department of Commerce (www.doc.gov), the Federal Trade Commission (www.ftc.gov), the Justice Department (www.usdoj.gov), and other regulatory agencies. Don’t forget that these larger departments have smaller, more focused units; Commerce, for example, houses the Census Bureau, which is a treasure trove of demographic data (https://data.census.gov/cedsci/). More locally, consult your state, county, or city website for business info closer to your backyard. (For just one example, the California State Association of Counties provides economic and related info at no cost to users:www.counties.org/data-and-research.) Finally, data collection isn’t limited to the United States. You may need to click the translate feature of your search engine, oui, but it can be worth the effort. (However, you better first brush up on those tricky meters and kilos.) - Trade associations: Many industries support trade groups that keep track of what goes on in their world. General business organizations, such as the chamber of commerce in your area, can also be quite useful in providing relevant information.

- Libraries: Business-school libraries are the best source of info, but public libraries also house numerous business periodicals and books, as well as hard-to-find academic references, industry newsletters, and even the annual reports of large corporations. In particular, check out the Dun & Bradstreet Industry Handbook, the Encyclopedia of Global Industries, the Handbook of North American Industry, or the Encyclopedia of Emerging Industries, just to name a few useful resources. Those dedicated folks who work there will love to see a live person again.

- Securities firms: Every major securities company — Schwab, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, Wells Fargo, whatever — has a research arm devoted to tracking various industries and their incumbents. The trick is to get your hands on the information. You may have to become a client in order to have access to their information, but it’s often incredibly detailed and forecasts prospects for the future. (Maybe ask old Gramps for the account password.)

- Colleges and universities: In addition to offering library resources, business schools often offer flesh-and-blood business experts. These people are paid to analyze, and every once in a while, they come up with a valuable insight or a really good idea. If you run across an expert in your industry, pay them a visit.

- Direct industry data and contacts: Go right to the source, if you can. All public companies in the United States are required to file comprehensive information on a timely basis with the SEC and other oversight agencies. Both annual and quarterly reports are in the public domain and freely accessible on the web. Start with the target firm’s website, which usually has a link to required financial reports and a tab for “news” that’s up to date. You can also find information at industry conventions and trade shows or through your advisory network, who might have insider knowledge of the firm. Finally, don’t hesitate to make a direct contact to the company’s PR department and see whether you can interview someone or take a factory tour. But probably best not to bring the camera.

Recognizing Critical Success Factors

Time spent doing careful industry analysis rewards you with a complete picture of the major forces at work in your business: the basic structure of your industry; your core markets; key relationships with suppliers, customers, and distributors; and profit margins and costs. The analysis can also point out trends in your industry and show you where your company is in terms of general industry and business cycles.

This information is all well and good. But how do you go about interpreting your industry landscape so that you can use it to improve your business planning? Just for fun, think about your industry as a great whitewater river. Imagine the many forces that you reviewed in the previous section as being the swift currents, dangerous rapids, haystacks, and even whirlpools in that river. You’re in the company canoe. You have to do more than just point out these features and paddle merrily along; you have to navigate around the hazards. As any whitewater expert can tell you, this means figuring out what needs to be done at every turn — what special skills, resources, and lines of communication need to be in place for you to survive and conquer each stretch of river. And think of this book as your paddle.

The CSFs for your company should be rather specific — a one-of-a-kind set of conditions based on your industry analysis and the forces that you see shaping your business. You probably don’t want to single out more than three or four CSFs at any one time. But no matter how many factors you believe are important, your CSFs are likely to fall into several general categories that you can identify ahead of time. In the following sections, we provide a starting point for creating your own CSF priorities.

Adopting new technologies, procedures, and policies

When digital commerce began to blossom in the early 2000s, it quickly became apparent that many retailers had to adopt this technology if they wanted to remain competitive. User-friendly digital capability became a CSF for industry incumbents. When reduced trade barriers led to the globalization of production, factories located in low-wage countries began to flood their products into advanced economies. If you couldn’t shift your own manufacturing abroad (“offshoring”) or get your workers to accept massive wage cuts (called “union busting”), you perished. These industry tectonics affected small businesses as well as large and challenged CSFs that had defined them in the past.

Getting a handle on what counts most

For manufactured commodity products such as steel or oil, large-scale mills or refineries are often the critical factors that lead to low-cost production and the capability to compete on price due to economies of scale. (For more information on economies of scale, refer to the earlier section “Overcoming barriers.”) Employees are becoming little more than appendages to automated machines in factories. In high-tech industries, on the other hand, victory in the “talent wars” may be the critical ingredient that allows for the creation of hot new products that keep the cash register ringing. Ditto for firms in investment banking or management consulting. Different industries have different CSF priorities. It’s usually a lot more complicated than “buy low, sell high.” Do you know yours? Keep reading for clues on how to find out.

Determining what drives your business

The long-term success of entertainment companies that consistently produce big (or these days little) screen hits and make money often hinges on organizational capabilities — the know-how to evaluate, organize, and manage site scouts, set designers and workers, production companies, as well as the media and distribution outlets that exhibit the last cut. And this says nothing of handling the fragile egos of the on- and off-screen creative talent.

In the health-care financing industry — a major subset of the nation’s largest business sector — goal achievement often stems from excelling in data management, efficiently steering hospitals and clinics, doctors, patients, medical suppliers, drugs, and insurance claims through a dysfunctional travesty masquerading as the health-care billing and reimbursement system.

Been to a casino lately? How do they make money? Not from the poker tables or that big spinning Wheel of Fortune. Those are for show. Profit comes primarily from keeping customers glued to their seats in front of the slots, where the odds are decidedly in the house’s favor. Come up with a trick to keep ’em glued down, such as having an hourly big prize paid to one randomly selected machine, and they’ll sit for hours in fear that the moment they move someone else will jump in and hit the jackpot on “their” seat. Seriously.

Looking for a great location

Supermarkets, retail drug stores, gas stations (remember when they were called “service” stations?) — it’s often the location of the business that spells success. Wonder why Pittsburgh was once the “steel capital” of America? Its location on rivers and roads provided ready and reasonably cheap access to the key raw materials that had to be hauled to the mills for conversion into iron and steel. If you’re interested in starting an outdoor entertainment venue, you might want to look into property around Orlando before trekking off to Buffalo. We think you see the drift here.

Dealing with distribution

Packaged foods, household products, snacks, and beverages often sink or swim depending on how much shelf space the supermarkets or local grocery stores allot to them. A successful packaged-goods company works hard to create incentives for everyone in the delivery chain, from the driver to the grocer, to make sure that store shelves have plenty of room for their brands, even squeezing out competing products. Speed of delivery and logistics can also be critical success factors, especially when freshness matters. Unfortunately, these kinds of stores finally caught on to what they were really selling — scarce space — so they began to charge “slotting” fees for the privilege of placing your product onto their shelf.

Marketing mind games

Manufacturers of cosmetics, clothing, perfume, and even CSDs (carbonated soft drinks like Coke) all sell hype and hope as much as they do the physical products themselves. In these cases, CSFs depend on the capability of companies to create and maintain strong brands. A brand represents the image of a particular product or service in the marketplace and how it affects consumer psychology. Just as food products fight for scarce shelf space at the supermarket, branded products are battling for the complex shelf space of your mind. In many markets, customers consider the name, the logo, or the label attached to a product before they buy the lipstick, jeans, or drinks that represent the brand.

Getting along with government regulation

Remember those weird words we use earlier in this chapter when discussing industry structure? Monopsony was one of them, and it refers to situations in which there is essentially only a single buyer for your offering. Governments are usually the target here (try selling your new ballistic missile system on Amazon; actually, please don’t). Companies that contract directly with public agencies, such as waste-management firms and public infrastructure construction companies like road builders, often succeed because of their unique capability (ahem …) to deal directly with bureaucrats and elected officials. Government regulation plays a role in many industries, and the know-how to navigate a swirling regulatory sea is often the critical factor in a company’s success. Pharmaceutical companies, for example, invest huge amounts of money in developing new drugs, and they stake all their potential profits and success on their skill in shepherding those “NCEs” (new chemical entities) through the Food and Drug Administration’s complex regulatory approval process.

SWOT: Preparing for Opportunities and Threats

After you have a handle on the major market forces that shape your industry and you can point out the critical success factors that determine what kind of company has the best shot at coming out on top, you can begin to look ahead. Using everything that you’ve discovered about how your industry works (see the earlier section “Analyzing Your Industry” to get started), what possibilities do you see for leveraging the company forward, and where do the potholes lie?

These kinds of questions often fall under the umbrella of something called situation analysis. When you think about it, your company’s situation depends partly on the structure of your organization and partly on things that happen outside, kind of a yin and yang in which you need to embrace the opposites and find ways to weave them both into your plans. These factors have long been in the playbook of business planners, located under the heading of “SWOT.” This acronym stands for strengths and weaknesses (internal factors to your organization) and opportunities and threats (the external angels and devils).

For the moment, we want to concentrate on the opportunities and threats that you may face. (Turn to Chapter 9 to work on your company’s strengths and weaknesses.) Opportunities and threats come from the forces, issues, trends, and events that exist beyond your control as a business planner and owner. They represent the challenges that your company has to tackle if you want to beat the competition. And today, in a world of historically high levels of disruption characterized by “VUCA” — volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity — it’s even doubly more difficult to read the tea leaves. But just because the task is daunting doesn’t imply it should be avoided. It can’t.

Finding warm and soothing waters

- Riding the wave of a new technology: When technologies change, existing companies are often slow to pick up on what’s new because they have so much invested in what’s old. They wallow in fantasies of a static environment that we call ROI: repression of innovation. The potential of new business opportunities is often left to the brave young upstarts willing to take risk, like Tesla in the EV (electric vehicle) space, usually because they have nothing to lose. What’s on the techno horizon in your industry? If it looks promising, what are you doing about it?

- Invention of new processes: Opportunity is often cloaked in a challenge. Some time ago Japan possessed the most expensive real estate on the planet. Manufacturers located there like Toyota Motors found it increasingly costly to build and manage parts and supply depots. So, they began to work closely with their suppliers to develop just-in-time (JIT) parts delivery systems. The partner would make the component and then deliver it directly to the Toyota assembly line ready for installation, thus eliminating the need for warehouses and contributing to significant cost savings. Necessity is the mother of invention.

- Finding new customer segments: New market opportunities are born when you can identify groups of customers who have been underserved or perhaps totally ignored by industry incumbents. The entire LGBTQ community was long the subject of discrimination by too many firms, even though data showed that people in such relationships had demonstrably higher levels of disposable income than those in heterosexual relationships. But then came Subaru, the smallish Japanese maker of cultish cars. As a niche marketer, promoting to groups like the outdoorsy crowd, it discovered that lesbians loved their products and, in fact, favored them four times as much as any other surveyed groups. Subaru launched a daring new ad campaign specifically targeting this demographic and has enjoyed a success that its larger and more well-endowed competitors haven’t.

- New uses for old products: Growth markets also spring up when firms find new uses for old products. We discuss earlier in this chapter how AM General repurposed its Humvee for civilians, but it was hardly the only one to spot a new opportunity. When medical researchers discovered that taking a small dose of acetylsalicylic acid a day could reduce the chance of a heart attack, aspirin became more than just an old-fashioned pain reliever. Pharmaceutical companies responded with new over-the-counter brands of “81” aspirin specifically designed for the new use and a new set of customers.

- Access to new pools of workers: Many industries have a shortage of human resources necessary to perform the available jobs. Business opportunities often arise when skilled workers become newly available, displacements from dying firms and industries or newly arrived immigrants fleeing catastrophe in their home nations or seeking new opportunities. Many of those who exit an industry are more strategic and resourceful than their cohorts; they are willing to take on new challenges and bring new ways of thinking into the game. In short, they open up opportunities for companies in need of a boost. Do you have the Hiring Now sign switched on and lighted — perhaps in a language besides English?

- Nontraditional new locations: Location means business opportunity. Starbucks used to be limited to its ubiquitous, green-starred locations around town. But then it convinced supermarket chains to free up a bit of space inside stores, which provided ready refreshment for current customers and drew in new ones seeking a quick brew. Customers love convenience. Where else can you spotlight your own products in addition to traditional locales?

- Bottom-of-the-pyramid opportunity: A number of years ago an influential academic researcher opened the eyes of businesspeople to the opportunities to be found “at the bottom of the pyramid” — that is, by reconfiguring products and services to better appeal to lower income and less advantaged groups in society. Collectively these folks represent an impressive amount of buying power, but traditional packing and distribution methods often overlooked their special needs. Is this an opportunity for you, too?

- Fresh organization models: New ways of doing business represent opportunities for the quick-witted. The pressure to downsize, for example, prompted firms to outsource all sorts of nonessential functions to other companies that do nothing but, say, manage IT, source and train staff, or undertake innovation and discovery projects. Can you offer your firm’s skills and talents to those organizations that want them but don’t see them as main jobs in their own operations — and, thus, might be willing to outsource the work to you? This is a win-win.

- New distribution channels: You rarely come across anything more exciting in the business world than finding a new way to connect with customers. We all now know by now how eBay’s founder stumbled across this amazing opportunity by trying to satisfy his girlfriend’s plea for an easier way to purchase flea market doodads. Think about how your own customers find your goods: Is there a better way?

- Changing laws or regulations: All levels of government (surprise, surprise) have a great deal to do with the way that companies operate in all sorts of industries. Have you taken your car in for its required smog check in California yet? Changing laws and regulation represent opportunities for firms to recalibrate how they grow sales and find new customers; track them and see what works.

Scanning for clouds on the horizon, ice on the water, or worse

Is your glass half full or half empty? Yeah, Pollyanna felt the same way — but that was a kid’s fantasy book, remember? We’re not knocking optimism, as entrepreneurs thrive on it, and so should you. But you’d be a fool to think the coin will always flip your way. Business is risk. For every big opportunity in an industry, you find an equally powerful threat to challenge the way in which you currently do business.

Consider the following external forces, grouped by category: Do any of them apply to your industry’s business environment? Do you have an escape hatch for the ifs and whens, or have you even thought about them? You might want to re-watch Titanic, mate. It’s called planning.

Technology threats include

- The digitization of everything

- The spread of AI and robotics

- Cybersecurity threats and IT hacking

Political threats include

- Political chaos and new or amended legislation

- New international trade and tariff laws

- Shifting patterns of global politics and power

Social threats include

- Newly empowered consumers

- Changing consumer preferences due to demographic shifts

- Growing income and wealth inequality

- Newly empowered employees

- FD&H (fat, dumb, and happy) management culture

Economic threats include

- New and aggressive competition, both foreign and domestic

- Substitute products and services

- Shortages of raw materials

- Loss of patent protection

- Organized labor demands

- Exchange-rate volatility

- Unanticipated disasters, natural and otherwise

- Anticipated disasters, but with no clear response and remediation programs

You can probably extend the list. But the problem isn’t how you check the box; these are forces usually beyond your control. It’s how you spot the threats coming in and then manage them to minimize damage. We deal more with this in Chapter 13, but for now let’s acknowledge that we’re at the inflexion point of a brave new world for business. Problems exist — indeed, VUCA on steroids. Get over it and act.

Okay, so what business are you really in? Don’t say that you’re in the widget business, if widgets are what you produce; go beyond the easy answer you base simply on what you do or what you make. You have to dig a bit deeper and ask yourself what makes your marketplace tick:

Okay, so what business are you really in? Don’t say that you’re in the widget business, if widgets are what you produce; go beyond the easy answer you base simply on what you do or what you make. You have to dig a bit deeper and ask yourself what makes your marketplace tick:  Make a list of all the major competitors in your industry, sometimes referred to as incumbents by the pointy-head crowd. Find out their sizes, based on revenue, profits, active users, production capacity, or some other readily available measure, and estimate their relative market shares for the markets that you want to explore. Try to get beyond just revenue numbers, as most industries have some telling metric specific to the industry that is more indicative of performance. For example, brick-and-mortar retailers are measured by sales per square foot, because in the end all they’re offering is space. Carefully choose keywords to take advantage of the extraordinary range of information on the Internet to gather as much data as you can find.

Make a list of all the major competitors in your industry, sometimes referred to as incumbents by the pointy-head crowd. Find out their sizes, based on revenue, profits, active users, production capacity, or some other readily available measure, and estimate their relative market shares for the markets that you want to explore. Try to get beyond just revenue numbers, as most industries have some telling metric specific to the industry that is more indicative of performance. For example, brick-and-mortar retailers are measured by sales per square foot, because in the end all they’re offering is space. Carefully choose keywords to take advantage of the extraordinary range of information on the Internet to gather as much data as you can find.