Chapter 12

Forecasting and Budgeting

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Forecasting your financial picture

Forecasting your financial picture

![]() Looking at financial alternatives

Looking at financial alternatives

![]() Forming your company’s budget

Forming your company’s budget

You’ve most likely sat down at the kitchen table at some point in your life to put together a household budget — when money was tight and you had to pinch every penny to cover all your bills. Everybody knows what a budget is, of course: a way to figure out how much you need to spend on essentials (rent, utilities, car payments) and incidentals (all the frills that you don’t exactly need, like that new set of golf clubs). By its very nature, a budget looks ahead and combines a forecast and a set of guidelines for spending money.

As you may know from experience, putting together a budget is much easier if you have some basic financial information to work with. You can take comfort in knowing how much money is going to come in, for example, and when you expect it to arrive. You also need to keep track of the essentials that you have to take care of immediately, such as the mortgage and the car payment. Only then can you find out what you have left over. In your business, the leftover is your working capital.

For your company, your financial picture resides in the financial statements you put together. Take a look at Chapter 11 (no, not Chapter 11 bankruptcy — the one in this book) for more statement information. These financial statements — income statements, balance sheets, and cash-flow statements — are fairly straightforward, because you base them on how your company has performed in the prior years. Unfortunately, financial information isn’t quite as easy to put together and use when you have to plan for next year, three years from now, or even five years down the road.

In this chapter, we help you construct a financial forecast for your company, including a pro-forma income statement, an estimated balance sheet, and a projected cash-flow statement. Because nothing in the future is certain, we also introduce scenario planning and what-if analysis as ways to consider several financial alternatives. Finally, we show you how you can use your financial forecast to create a budget.

Constructing a Financial Forecast

So far, no one has found a way to accurately predict every detail of the future. The only thing we know for certain is that we face an uncertain future.

You make decisions every day based on your personal views of what lies ahead. Although situations may often end up surprising you, your assumptions about the future at least give you the basic framework to plan your life. Your expectations, no matter how outlandish, encourage you to set objectives, move forward, and achieve your goals somewhere down the road.

You can think about the future of your company in much the same way. Assumptions about your industry and marketplace — that you’ll have no new competitors, that a new technology will catch on, or that customers will remain loyal, for example — provide a framework to plan around. Your expectations of what lies ahead influence your business objectives and the long-term goals you set for the company.

- Everybody who looks at your forecast knows exactly what’s behind it.

- You know exactly where to go when you need to change your assumptions.

As you may have experienced elsewhere in life, coming up with predictions that you really believe in isn’t always easy. You may trust some numbers (next year’s sales figures) more than you do others (the size of an untested brand-new market). Your best estimates form the basis of some of your financial predictions, and you may use sophisticated number-crunching techniques to arrive at others. After you get the hang of it, you begin to see what a powerful and useful planning tool a financial forecast can be. You find yourself turning to it to help answer all sorts of important questions, such as these:

- What cash demands does your business face in the coming year?

- Can your company cover its debt obligations over the next three years?

- Does your business plan lead to profitability this year?

- Unrealistic expectations

- Nonobjective assumptions

- Unchecked predictions

The following sections examine the financial statements that make up a financial forecast. After we explain how you can put these statements together, we point out which of the numbers are most important and which are the most sensitive to changes.

Piecing together your pro-forma income statement

Pro forma refers to something that you describe or estimate in advance. (It can also signify a mere formality that you can ignore — but don’t get your hopes up; we’re talking about a serious part of a business plan.) When you construct your financial forecast, you should include pro-forma income statements — documents that show where you plan to get your money and how you plan to spend it — for at least three years and for as long as five years into the future, depending on the nature of your business. You should subdivide the first two years into quarterly income projections. After two years, when your income projections are much less certain, annual projections are fine. (For info on income statements, go to Chapter 11.)

- If you’re already in business and have a financial history to work with, upload all your past financial statements right away. (If these are not already in a spreadsheet format like Excel, then convert them to one.) You can use them to help you figure out what’s likely to happen next.

- If you run or are developing a new company and you don’t have a history to fall back on, you have to find other ways to get information on expected revenues and costs. Talk to people in similar businesses, and consult industry data through links on the Internet and other informative media.

The pro-forma income statement has two parts: projected revenue and anticipated costs.

Projected revenue

Your company’s projected revenue is based primarily on your sales forecast — exactly how much of your product or service you plan to sell. You have to think about two things: how much you expect to sell, naturally, and how much you want to charge. Unfortunately, you can’t completely separate the two projections, because any change in price usually affects the level of your sales (price up, volume down, and vice versa).

How do you make an accurate sales forecast? Start by looking at this formula:

Sales forecast = Market size × Growth rate × Market-share target

- Market size estimates the current number of potential customers or units of the good.

- Growth rate estimates the speed of market growth.

- Market-share target estimates the percentage of the market that you plan to capture.

Because your sales forecast has such a tremendous impact on the rest of your financial forecast — not to mention on the company itself — you should try to support your estimates with as much hard data as you can get. Depending on your situation, you can also rely on the following guides:

- Company experience: If you have experience and a track record in the market, you can use your sales history to make a sales prediction.

- Industry data: Industry data on market size and estimates of future growth come from all quarters, including trade associations, investment companies, and market-research firms (which we cover more extensively in Chapter 5).

Outside trends: In certain markets, sales levels mirror trends in other markets, social trends, or economic trends (a phenomenon we describe in Chapter 13).

Even if a product is brand-new, you can sometimes find a substitute market to track as a reference. When frozen yogurt first appeared on the scene, for example, its producers turned to the sales history of ice cream to help support their sales forecasts.

Projected revenue = Sales forecast (in units of your good) × Average price

Where does the average price come from? You base your average price on what you think your customers are willing to pay and what your competitors charge (refer to Part 2 for more information on how to analyze your industry and customers).

Now put all the numbers together and see how they work. We use an imaginary company called Yenta’s Yogurt (YY) as an example. Sally Smart, the flavored yogurt product manager, starts putting together a three-year revenue projection. Utilizing industry and market data along with sales history, Sally estimates that the entire market for flavored yogurts will grow about 10 percent a year and that YY’s market share will increase by roughly 2 percent a year, with projected price increases of approximately $1 to $2 per case of 12 yogurt containers (a very positive projection — you can’t always assume that market share and prices will increase). She puts the numbers together in a table so that she can easily refer to the underlying estimates and the assumptions that support them (see Table 12-1). All of this should be done in an Excel spreadsheet (or comparable tool) so you can quickly tweak numbers and see the overall effect.

TABLE 12-1 Flavored Yogurt Revenue Projection for Yenta’s Yogurt Co. (YY)

Revenue Projection | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

Projected total market size (units) | 210,000 | 231,000 | 254,100 |

Projected YY market share (%) | 20 | 22 | 24 |

Sales forecast (units) | 42,000 | 50,820 | 60,980 |

Average price | $26 | $27 | $29 |

Projected revenue | $1,092,000 | $1,372,140 | $1,768,420 |

Anticipated costs

You still have to look at anticipated costs — the price tag of doing business over the next several years. To make life a little easier, you can break anticipated costs into the major categories that appear in a pro-forma income statement: projected cost of goods sold; projected sales, general, and administration expenses; projected interest expenses; and projected taxes and depreciation (flip to Chapter 11 for more details). The following list defines these categories:

Projected cost of goods sold (COGS): COGS, which combines all the direct costs associated with putting together your product or delivering your service, is likely to be your single largest expense.

Although the following formula may look ugly, treat it as a simple way to calculate your projected COGS. Based on the assumption that the ratio of your costs to your revenue will stay the same,

- Projected COGS = (Current COGS ÷ Current revenue on sales) × Projected revenue

Sales, general, and administration (SG&A): SG&A represents your company’s overhead: sales expenses, advertising, travel, accounting, telephones, and all the other costs associated with supporting your business. If your company is brand-new, try to get a feel for what your support costs may be by asking people in similar businesses, cornering your accountant, or checking with a trade association for average support costs in your industry. There also may be something online that can help you here, so don’t be afraid to use that source.

If you have a mature business, you can estimate a range for your SG&A expenses by using two calculations:

- The first method projects a constant spending level, even if your company’s sales start growing. In effect, you assume that your support activities will all get more efficient and accommodate your additional growth without getting bigger themselves.

- The other method projects a constant SG&A-to-revenue ratio. In this case, you assume that support costs will grow as fast as your revenue without any increase in efficiency. Because your projected SG&A costs are higher, this is the more conservative estimate.

An accurate SG&A forecast probably lies somewhere in between. Given what you know about your company’s operations, come up with your own estimate and include the assumptions that you make.

An accurate SG&A forecast probably lies somewhere in between. Given what you know about your company’s operations, come up with your own estimate and include the assumptions that you make.- Interest expense: Your interest expense largely results from decisions that you make about your company’s long-term financing. Think about what sort of financing your business may need in the future (to acquire office space, computers, machinery, and so on) and what interest rates you may be able to lock in, and then estimate your interest expense as best you can.

Taxes and depreciation: Taxes certainly affect your bottom line, and you want to include your projections and assumptions in your anticipated costs. You usually can estimate the general impact taxes may have on the future by looking at their impact on your company now.

Depreciation, on the other hand, is an accountant’s way of tracking the value that your purchases (equipment, tools, whatever) lose over time. As such, depreciation expense doesn’t really come out of your pocket every year. You can estimate the numbers, but don’t get too carried away.

Estimating your balance sheet

The second part of your financial forecast is the estimated balance sheet, which, like a regular balance sheet (see Chapter 11), serves as a snapshot of what your company looks like at a particular moment — what it owns, what it owes, and what it’s worth. Your estimated balance sheets describe what you want your company to become in the future and how you plan to achieve your goal. The estimated balance sheets that you put together as parts of your financial forecast should start with the present and extend out three to five years in a series of year-end projections.

The pro-forma income statements in your financial forecast project future revenue, costs, and profits; your estimated balance sheets lay out exactly how your company needs to grow so that it can meet those projections. First, you want to look at what sorts of assets you need to support the planned size and scale of your business. After you assess your necessary assets, you have to consider how to finance your company — how much debt you plan to take on (liabilities) and how much of your investors’ money (equity) you plan to use.

Assets

Your company’s projected assets at the end of each year include everything from the money that you expect to have in the petty-cash drawer to the buildings and machines that you plan to own. Some are current assets, meaning that you can easily turn them into cash; others are fixed assets, which take much longer to get rid of (refer to Chapter 11 for detailed asset info).

Current assets: The cash you have on hand, as well as accounts receivable and inventories, add up to your current assets. How much should you plan for? That depends on the list of current liabilities (debts) you expect to have, because you have to pay short-term debts out of your current assets. What you have left over is your working capital.

Projected inventories (the amount of product in your warehouse) depend on how fast your company can put together products or services and get them to customers.

Fixed assets: Land, buildings, equipment, machinery, and other assets you can’t easily dispose of make up your company’s fixed assets. Your estimated balance sheets should account for the big-ticket items that you expect to purchase or get rid of.

Keep an eye on how each machine or piece of equipment helps your bottom line. If you plan to buy something big, make a quick calculation of its payback period (how long it takes to pay back the initial cost of the equipment out of the extra profit that you make). Here’s a simple example: There’s a new machine out there that you can purchase for $10,000. If you buy it, it will reduce your current costs with your existing machine by $3,333 a year. So, in three years the savings equals the cost of the machine: $10,000 ÷ $3,333 = 3). Your payback period is then three years. Is the payback period going to be months, years, or decades? If the payback period you foresee is longer than you’d like, consider an equipment lease as an alternative to an outright purchase.

Keep an eye on how each machine or piece of equipment helps your bottom line. If you plan to buy something big, make a quick calculation of its payback period (how long it takes to pay back the initial cost of the equipment out of the extra profit that you make). Here’s a simple example: There’s a new machine out there that you can purchase for $10,000. If you buy it, it will reduce your current costs with your existing machine by $3,333 a year. So, in three years the savings equals the cost of the machine: $10,000 ÷ $3,333 = 3). Your payback period is then three years. Is the payback period going to be months, years, or decades? If the payback period you foresee is longer than you’d like, consider an equipment lease as an alternative to an outright purchase.

Liabilities and owners’ equity

Estimated balance sheets have to balance, of course, and your projected assets at the end of each future year have to be offset by all the liabilities (current and long-term) that you intend to take on, plus your projected equity in the company. Think about how leveraged you intend to be (how much of your total assets you expect to pay for out of money that you borrow). Your use of leverage in the future says a great deal about your company.

- Current liabilities: You estimate in this category all the money that you expect to owe on a short-term basis in the future. Current liabilities include the amounts that you expect to owe other companies as part of your planned business operations, as well as payments you expect to send to the tax people.

Long-term liabilities: The long-term debt that you plan to take on represents the piece of your company that you intend to finance. Don’t be surprised, however, if potential creditors put a strict limit on how much they want to loan you, especially if you’re new to the business. In general, bankers and bondholders alike want to see enough equity put into your business to make them think that everyone is in the same boat, risk-wise.

Before you take on a new loan, find out what kind of debt-to-equity ratios similar companies have (for help, turn to Chapter 11). Make sure that yours falls somewhere in the same range.

Owners’ equity: The pieces of your company that you, your friends, relatives, acquaintances, and often total strangers lay claim to get lumped together as owners’ equity.

In general, you can estimate your company’s future benefit for the owners by projecting the return that you expect to make on the owners’ investment (refer to Chapter 11 for the details). You can compare that return with the earnings of investors in other companies or even other industries.

During the initial stages of your company, equity capital likely comes from the owners themselves — as cash straight out of the wallet or from the sale of stock to other investors. The equity at this stage is crucial, because if you want to borrow money later, you have to show your bankers that you have enough invested in your business to make your company a sound financial risk.

Unfortunately, profits have another side — a down side residing in the red. Although you probably don’t want to think about it, your company may lose money some years (especially during the early years). Losses don’t generate equity; on the contrary, they eat up equity. So you have to plan to have enough equity available to cover any anticipated losses that you project in your pro-forma income statements (refer to the earlier section “Piecing together your pro-forma income statement”).

Unfortunately, profits have another side — a down side residing in the red. Although you probably don’t want to think about it, your company may lose money some years (especially during the early years). Losses don’t generate equity; on the contrary, they eat up equity. So you have to plan to have enough equity available to cover any anticipated losses that you project in your pro-forma income statements (refer to the earlier section “Piecing together your pro-forma income statement”).

Projecting your cash flow

The flow of cash through a business is much like the flow of oil through an engine: It supports and sustains everything you do and keeps the various parts of your company functioning smoothly. We all know what happens when a car’s oil runs dry: The car belches blue smoke and dies. Running out of cash can be just as catastrophic for your company. If you survive the experience, it may take months or even years for your business to recover.

Cash-flow statements keep track of the cash that comes in and out of your company, as well as where the money ends up. Projected cash-flow statements ensure that you never find the cash drawer empty at the end of the month when you have bills to pay.

Exploring Alternative Financial Forecasts

Wouldn’t it be nice if you could lay out a financial forecast — create your pro-forma income statements, estimated balance sheets, and projected cash-flow statements — and be done with it? Unfortunately, the uncertain future that makes your financial forecast necessary in the first place is unpredictable enough to require constant attention. To keep up, you have to do the following things:

- Monitor your financial situation and revise the parts of your forecast that change when circumstances — and your financial objectives — shift.

- Update the entire financial forecast regularly, keeping track of the accuracy of your past predictions and extending your projections another month, quarter, or year.

- Consider financial assumptions that appear more optimistic and more pessimistic when compared to your best predictions, paying special attention to the estimates that you feel the least certain about.

Utilizing the DuPont formula

If you want to get a feel for what happens when you change any of the estimates that make up your company’s financial forecast, you have to understand how the numbers relate to one another. The DuPont company came up with a useful formula that other companies have used since its inception over 100 years ago (some old things are worth keeping around).

The idea behind the DuPont formula is simple: to describe all the ingredients that play a role in determining your return on equity (ROE) — a number that captures the overall profitability of your company. ROE is your company’s overall net profit divided by the owners’ equity. But knowing that your ROE is 13 percent, for example, is like getting a B+ on a test. You think that you did relatively well, but why did you get that particular grade? Why didn’t you get an A? You want to know what contributed to the grade so that you can do better next time.

- First level

- ROE = Return on assets (ROA) × Leverage

- You can increase your company’s return on equity by increasing the overall return on your company assets or by increasing your leverage (the ratio of your total company assets to equity).

- Second level

- Leverage = Assets ÷ Equity

- As your debt increases relative to equity, so does your company’s leverage.

- ROA = Asset turnover × Net profit margin

- You can increase your return on company assets by turning those assets into more sales or by increasing the amount of money that you make on each sale.

- Third level

- Asset turnover = Sales ÷ Assets

- Asset turnover is the amount of money that you take in on sales relative to your company’s assets. The bigger your asset turnover, the more efficiently you turn assets into sales.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 12-1: The DuPont chart turns the DuPont formula into a pyramid, with return on equity (ROE) at the top.

- Net profit margin = Net profit ÷ Sales

- Net profit margin is the profit that you make after subtracting expenses divided by the amount of money you take in on sales. The larger your profit margin, the lower your overall costs relative to the prices that you charge.

Answering a what-if analysis

After you see the makings of the DuPont formula (outlined in the previous section), you can start exploring different assumptions and what happens when you change the financial forecast. With the DuPont formula, you can look at how those changes can affect your projected profitability, measured by your return on equity. The DuPont formula makes answering questions like the following much easier:

- What if I cut prices by 3 percent?

- What if I increase sales volume by 10 percent?

- What if the cost of goods sold (COGS) goes up by 8 percent?

- What if I reduce company leverage by 25 percent?

Making a Budget

The pieces of your financial forecast — the pro-forma income statements, estimated balance sheets, and projected cash-flow statements — are meant to create a moving picture of your financial situation tomorrow, next month, next year, and three or even five years out. You can see a much clearer financial picture in the near term, of course, with your viewpoint clouding up the farther out you try to look. Fortunately, you can use the best of your forecasts to make near-term decisions about where, when, and how much money to spend on your company in the future.

Looking inside the budget

The rough outlines of your company’s budget look a lot like your projected cash-flow statement. In fact, the cash-flow statement is the perfect place to start. Projected cash flow is a forecast of your company’s projected money sources and where your funds may go in the future (check out the earlier section “Projecting your cash flow” for a deeper look). Your budget fills in all the details, turning your financial forecast into a specific plan for taking money in and doling it out. The master budget that you create should account for everything that your company plans to do over the next year or two.

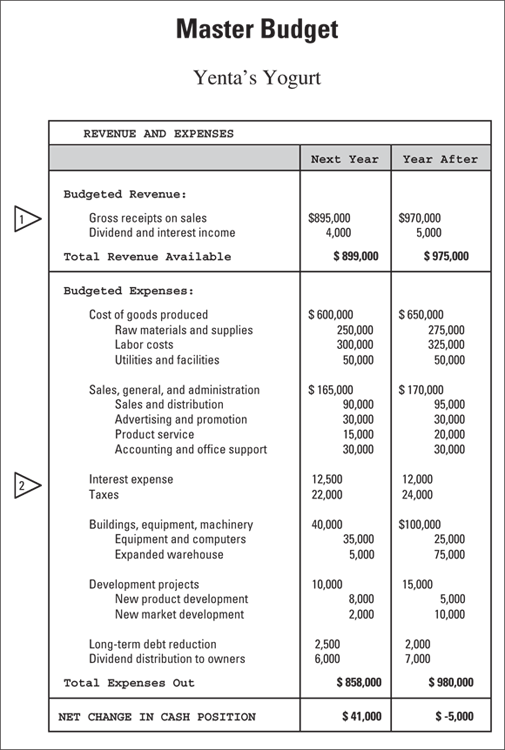

Yenta’s Yogurt put together a budget for the next two years based on a financial forecast and its projected cash flow (see Figure 12-2). The company’s master budget looks a great deal like one of its cash-flow statements (flip to Chapter 11 for a comparison). But the budget goes into more detail in dividing the broad financial objectives into actual revenue and expense targets for specific company activities. The company breaks down the cost of goods produced, for example, into the cost of raw materials and supplies, labor, utilities, and facilities.

Creating your budget

So when should you begin? If you’re just starting your business — or find yourself in a company without a budget in place — what better time than the present? If you’re up and running, when you start the new budget cycle depends on your company’s size. For big companies, the yearly budget process should begin six to nine months in advance.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 12-2: The master budget resembles a projected cash-flow statement.

There’s a better way, by using an approach called zero-based budgeting. When you insist on zero-based budgeting, you ask everybody — including yourself — to go back and start from ground zero to prepare the budget. Instead of depending on last year’s budget numbers, you make full use of your financial forecast and build up a new set of numbers from scratch. You also are able to fundamentally question each and every item in the projected budget for the coming year, which in these current times of constant and radical change is especially critical.

Top-down budgeting approach

Put the finishing touches on your company’s financial forecast, including the pro-forma income statements, expected balance sheets, and projected cash-flow statements.

If certain pieces are missing or incomplete, try to get the information that you need or make a note that a necessary document is unavailable. (Check out the earlier section “Constructing a Financial Forecast” to form the pieces of the forecast.)

Meet with your company’s decision-makers (or your trusted group, if you’re self-employed) to review the financial forecast.

Take time to discuss your general expectations about the future. Talk about the business assumptions that go into the forecast and the key predictions and estimates that come out of it.

Meet again to explore possible financial alternatives.

After everyone has had a chance to reflect on the financial forecast, look at different sets of business assumptions and weigh their potential effects on the forecast.

- Come up with revenue and expense targets for each of your company’s major business activities or functional areas (whichever is more appropriate to your company).

Meet one last time after you draft the budget to review the numbers and to make sure that everyone is on board.

Put together a written summary to go along with the numbers so that everyone in the company knows what the budget is, where it comes from, and what it means.

Bottom-up budgeting approach

The bottom-up approach to creating your budget is an expanded version of the top-down process, but it takes into account the demands of a bigger company and of more people who have valuable input. You still want to begin creating your budget by getting a group of senior managers together. That group should still spend time coming to a general understanding of, and agreement on, your company’s financial forecast. But instead of forcing a budget from the top, the bottom-up approach allows you to build the budget up through the company.

Meet with senior managers and ask them to review the company’s broad financial objectives for each of your major business areas.

Try to come up with guidelines that set the tone and direction for budget discussions and negotiations throughout the company. (See the earlier section “Constructing a Financial Forecast” to come up with objectives.)

Ask the top managers to meet with their managers and supervisors at all levels in the organization.

Meetings can start with a recap of the budget guidelines, but the discussions should focus on setting revenue and expense targets. After all, these division managers actually have to achieve the numbers and stay within the spending limits.

Summarize the results of the budget negotiations.

If necessary, get the senior group members together again to discuss revisions in the financial objectives, based on the insights, perceptions, and wisdom of the company’s entire management team.

Approve the budget at the top.

In this final pass, look at the overall budget not only in terms of current financial objectives, but also with respect to your larger business goals.

One final point about your organization’s budget: After you’re done with all the negotiating and “put the budget to bed,” everyone knows their budget allocation for the coming year. This implies that you’ve created an incentive tool for your managers and everyone else in the firm. Achieve the budgeted numbers, and you get a bump to your salary and bonus if the firm provides one. Most people live in the here and now, not three or five or further years out. So, to get that bonus, your team will work as hard as possible to make their numbers. But here’s the tricky part: How tightly aligned with your long-term strategy is this next-year’s budget? Suppose, for example, your long-term strategic goal is to become the perceived quality leader in your industry. Next, suppose that the budget for your operations department calls for a bonus if the managers there can cut expenses by 10 percent over the coming year. Do you want to guess which target those good folks will strive for? Whatever puts money in the pocket today.

Why go to all the trouble of predicting your finances in the first place? The answer is simple: Although the financial estimates and forecasts aren’t your business plan by themselves, they support your business plan in critical ways. Without them, you face the real danger of allowing your financial condition — money (or the lack of it) — to take control of, or even replace, your business plan.

Why go to all the trouble of predicting your finances in the first place? The answer is simple: Although the financial estimates and forecasts aren’t your business plan by themselves, they support your business plan in critical ways. Without them, you face the real danger of allowing your financial condition — money (or the lack of it) — to take control of, or even replace, your business plan.