Chapter 19. Understanding Ansible, Puppet, and Chef

This chapter covers the following exam topics:

6.0 Automation and Programmability

6.6 Recognize the capabilities of configuration mechanisms Puppet, Chef, and Ansible

By now, you have seen how to use the IOS CLI to configure routers and switches. To configure using the CLI, you get into configuration mode, issue configuration commands (which change the running-config file), and eventually leave configuration mode. If you decide to keep those changes, you save the configuration to the startup-config file using the copy running-config startup-config command. Next time the router or switch boots, the device loads the startup-config file into RAM as the running-config. Simple enough.

This chapter discusses tools for configuration management that replaces that per-device configuration process. To even imagine what these tools do first requires you to make a leap of imagination to the everyday world of a network engineer at a medium to large enterprise. In a real working network, managing the configuration of the many networking devices creates challenges. Those challenges can be addressed using that same old “use configuration mode on each device” process, plus with hard work, attention to detail, and good operational practices. However, that manual per-device process becomes more and more difficult for a variety of reasons, so at some point, enterprises turn to automated configuration management tools to provide better results.

The first section of this chapter takes a generalized look at the issues of configuration management at scale along with some of the solutions to those problems. The second major section then details each of three configuration management tools—Ansible, Puppet, and Chef—to define some of the features and terms used with each. By the end of the chapter, you should be able to see some of the reasons why these automated configuration management tools have a role in modern networks and enough context to understand as you pick one to investigate for further reading.

“Do I Know This Already?” Quiz

Take the quiz (either here or use the PTP software) if you want to use the score to help you decide how much time to spend on this chapter. The letter answers are listed at the bottom of the page following the quiz. Appendix C, found both at the end of the book as well as on the companion website, includes both the answers and explanations. You can also find both answers and explanations in the PTP testing software.

Table 19-1 “Do I Know This Already?” Foundation Topics Section-to-Question Mapping

Foundation Topics Section |

Questions |

Device Configuration Challenges and Solutions |

1–3 |

Ansible, Puppet, and Chef Basics |

4, 5 |

1. Which answer best describes the meaning of the term configuration drift?

Changes to a single device’s configuration over time versus that single device’s original configuration

Larger and larger sections of unnecessary configuration in a device

Changes to a single device’s configuration over time versus other devices that have the same role

Differences in device configuration versus a centralized backup copy

2. An enterprise moves away from manual configuration methods, making changes by editing centralized configuration files. Which answers list an issue solved by using a version control system with those centralized files? (Choose two answers.)

The ability to find which engineer changed the central configuration file on a date/time

The ability to find the details of what changed in the configuration file over time

The ability to use a template with per-device variables to create configurations

The ability to recognize configuration drift in a device and notify the staff

3. Configuration monitoring (also called configuration enforcement) by a configuration management tool generally solves which problem?

Tracking the identity of individuals who changed files, along with which files they changed

Listing differences between a former and current configuration

Testing a configuration change to determine whether it will be rejected or not when implemented

Finding instances of configuration drift

4. Which of the following configuration management tools uses a push model to configure network devices?

Ansible

Puppet

Chef

None use a push model

5. Which of the following answers list a correct combination of configuration management tool and the term used for one of its primary configuration files? (Choose two answers.)

Ansible manifest

Puppet manifest

Chef recipe

Ansible recipe

Answers to the “Do I Know This Already?” quiz:

1 C

2 A, B

3 D

4 A

5 B, C

Foundation Topics

Device Configuration Challenges and Solutions

Think about any production network. What defines the exact intended configuration of each device in a production network? Is it the running-config as it exists right now or the startup-config before any recent changes were made or the startup-config from last month? Could one engineer change the device configuration so that it drifts away from that ideal, with the rest of the staff not knowing? What process, if any, might discover the configuration drift? And even with changes agreed upon by all, how do you know who changed the configuration, when, and specifically what changed?

Traditionally, CCNA teaches us how to configure one device using the configure terminal command to reach configuration mode, which changes the running-config file, and how to save that running-config file to the startup-config file. That manual process provides no means to answer any of the legitimate questions posed in the first paragraph; however, for many enterprises, those questions (and others) need answers, both consistent and accurate.

Not every company reaches the size to want to do something more with configuration management. Companies with one network engineer might do well enough managing device configurations, especially if the network device configurations do not change often. However, as a company moves to multiple network engineers and grows the numbers of devices and types of devices, with higher rates of configuration change, manual configuration management has problems.

This section begins by discussing a few of these kinds of configuration management issues so that you begin to understand why enterprises need more than good people and good practices to deal with device configuration. The rest of the section then details some of the features you can find in automated configuration management tools.

Configuration Drift

Consider the story of an enterprise of a size to need two network engineers, Alice and Bob. They both have experience and work well together. But the network configurations have grown beyond what any one person can know from memory, and with two network engineers, they may remember different details or even disagree on occasion.

One night at 1 a.m., Bob gets a call about an issue. He gets into the network from his laptop and resolves the problem with a small configuration change to branch office router BR22. Alice, the senior engineer, gets a different 4 a.m. call about another issue and makes a change to branch office router BR33.

The next day gets busy, and neither Alice nor Bob mentions the changes they made. They both follow procedures and document the changes in their change management system, which lists the details of every change. But they both get busy, the topic never comes up, and neither mentions the changes to each for months.

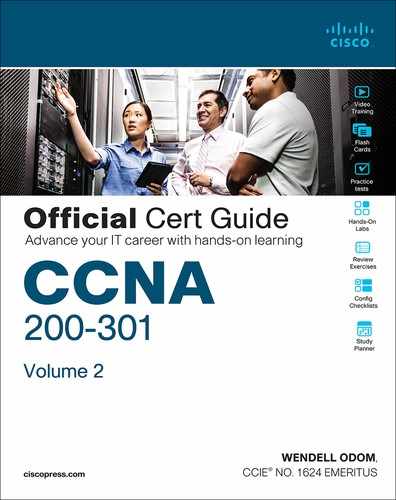

The story shows how configuration drift can occur—an effect in which the configuration drifts away from the intended configuration over time. Alice and Bob probably agree to what a standard branch office router configuration ought to look like, but they both made an exception to that configuration to fix a problem, causing configuration drift. Figure 19-1 shows the basic idea, with those two branch routers now with slightly different configurations than the other branch routers.

Figure 19-1 Configuration Drift in Branch Routers BR22 and BR33

Configuration drift becomes a much bigger problem if using only traditional manual configuration tools. For instance:

The on-device manual configuration process does not track change history: which lines changed, what changed on each line, what old configuration was removed, who changed the configuration, when each change was made.

External systems used by good systems management processes, like trouble ticketing and change management software, may record details. However, those sit outside the configuration and require analysis to figure out what changed. They also rely on humans to follow the operational processes consistently and correctly; otherwise, an engineer cannot find the entire history of changes to a configuration.

Referring to historical data in change management systems works poorly if a device has gone through multiple configuration changes over a period of time.

Centralized Configuration Files and Version Control

The manual per-device configuration model makes great sense for one person managing one device. With that model, the one network engineer can use the on-device startup-config as the intended ideal configuration. If a change is needed, the engineer gets into configuration mode and updates the running-config until happy with the change. Then the engineer saves a copy to startup-config as the now-current ideal config for the device.

The per-device manual configuration model does not work as well for larger networks, with hundreds or even thousands of network devices, with multiple network engineers. For instance, if the team thinks of the startup-config of each device as the ideal configuration, if one team member changes the configuration (like Alice and Bob each did in the earlier story), no records exist about the change. The config file does not show what changed, when it changed, or who changed it, and the process does not notify the entire team about the change.

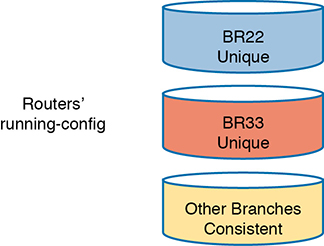

As a first step toward better configuration management, many medium to large enterprises store configurations in a central location. At first, storing files centrally may be a simple effort to keep backup copies of each device’s configuration. They would, of course, place the files in a shared folder accessible to the entire network team, as shown in Figure 19-2.

Figure 19-2 Copying Device Configurations to a Central Location

Which configuration file is the single source of truth in this model? The configuration files still exist on each device, but now they also exist on a centralized server, and engineers could change the on-device configuration as well as the text files on the server. For instance, if the copy of BR21’s configuration on the device differs from the file on the centralized server, which should be considered as correct, ideal, the truth about what the team intends for this device?

In practice, companies take both approaches. In some cases, companies continue to use the on-device configuration files as the source of truth, with the centralized configuration files treated as backup copies in case the device fails and must be replaced. However, other enterprises make the transition to treat the files on the server as the single source of truth about each device’s configuration. When using the centralized file as the source of truth, the engineers can take advantage of many configuration management tools and actually manage the configurations more easily and with more accuracy.

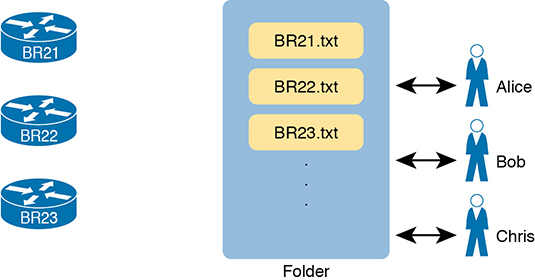

For example, configuration management tools use version control software to track the changes to centralized configuration files, noting who changes a file, what lines and specific characters changed, when the change occurred, and so on. The tools also allow you to compare the differences between versions of the files over time, as shown in Figure 19-3.

Figure 19-3 Showing File Differences in GitHub

The figure shows a sample of a comparison between two versions of a configuration file. The upper two highlighted lines, with the minus signs, show the lines that were changed, while the two lower highlighted lines, with the plus signs, show the new versions of each line.

Version control software solves many of the problems with the lack of change tracking within the devices themselves. Figure 19-3 shows output from a popular software-as-a-service site called GitHub (www.github.com). GitHub offers free and paid accounts, and it uses open-source software (Git) to perform the version control functions.

Configuration Monitoring and Enforcement

With a version control system and a convention of storing the configuration files in a central location, a network team can do a much better job of tracking changes and answering the who, what, and when of knowing what changed in every device’s configuration. However, using that model then introduces other challenges—challenges that can be best solved by also using an automated configuration management tool.

With this new model, engineers should make changes by editing the associated configuration files in the centralized repository. The configuration management tool can then be directed to copy or apply the configuration to the device, as shown in Figure 19-4. After that process completes, the central config file and the device’s running-config (and startup-config) should be identical.

Figure 19-4 Pushing Centralized Configuration to a Remote Device

Using the model shown in Figure 19-4 still has dangers. For instance, the network engineers should make changes by using the configuration management tools, but they still have the ability to log in to each device and make manual changes on each device. So, while the idea of using a configuration management tool with a centralized repository of config files sounds appealing, eventually someone will change the devices directly. Former correct configuration changes might be overwritten, and made incorrect, by future changes. In other words, eventually, some configuration drift can occur.

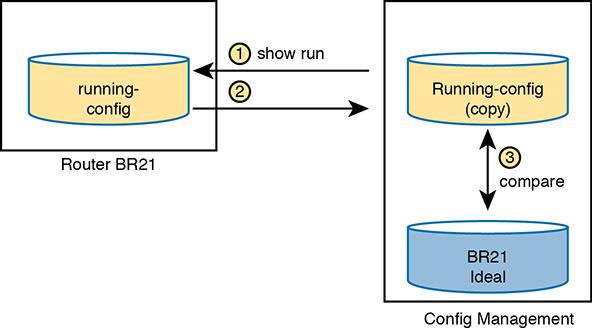

Configuration management tools can monitor device configurations to discover when the device configuration differs from the intended ideal configuration, and then either reconfigure the device or notify the network engineering staff to make the change. This feature might be called configuration monitoring or configuration enforcement, particularly if the tool automatically changes the device configuration.

Figure 19-5 shows the general idea behind configuration monitoring. The automated configuration management software asks for a copy of the device’s running-config file, as shown in steps 1 and 2. At step 3, the config management software compares the ideal config file with the just-arrived running-config file to check whether they have any differences (configuration drift). Per the configuration of the tool, it either fixes the configuration or notifies the staff about the configuration drift.

Figure 19-5 Configuration Monitoring

Configuration Provisioning

Configuration provisioning refers to how to provision or deploy changes to the configuration once made by changing files in the configuration management system. As one of the primary functions of a configuration management tool, you would likely see features like these:

The core function to implement configuration changes in one device after someone has edited the device’s centralized configuration file

The ability to choose which subset of devices to configure: all devices, types with a given attribute (such as those of a particular role), or just one device, based on attributes and logic

The ability to determine if each change was accepted or rejected, and to use logic to react differently in each case depending on the result

For each change, the ability to revert to the original configuration if even one configuration command is rejected on a device

The ability to validate the change now (without actually making the change) to determine whether the change will work or not when attempted

The ability to check the configuration after the process completes to confirm that the configuration management tool’s intended configuration does match the device’s configuration

The ability to use logic to choose whether to save the running-config to startup-config or not

The ability to represent configuration files as templates and variables so that devices with similar roles can use the same template but with different values

The ability to store the logic steps in a file, scheduled to execute, so that the changes can be implemented by the automation tool without the engineer being present

The list could go further, but these features outline some of the major features included in all of the configuration management tools discussed in this chapter. Most of the items in the list revolve around editing the central configuration file for a device. However, the tools have many more features, so you have more work to do to plan and implement how they work. The next few pages focus on giving a few more details about the last two items in the list.

Configuration Templates and Variables

Think about the roles filled by networking devices in an enterprise. Focusing on routers for a moment, routers often connect to both the WAN and one or more LANs. You might have a small number of larger routers connected to the WAN at large sites, with enough power to handle larger packet rates. Smaller sites, like branch offices, might have small routers, maybe with a single WAN interface and a single LAN interface; however, you might have a large number of those small branch routers in the network.

For any set of devices in the same role, the configurations are likely similar. For instance, a set of branch office routers might all have the exact same configuration for some IP services, like NTP or SNMP. If using OSPF interface configuration, routers in the same OSPF area and with identical interface IDs could have identical OSPF configuration.

For instance, Example 19-1 shows a configuration excerpt from a branch router, with the unique parts of the configuration highlighted. All the unhighlighted portions could be the same on all the other branch office routers of the same model (with the same interface numbers). An enterprise might have dozens or hundreds of branch routers with nearly identical configuration.

Example 19-1 Router BR1 Configuration, with Unique Values Highlighted

hostname BR1 ! interface GigabitEthernet0/0 ip address 10.1.1.1 255.255.255.0 ip ospf 1 area 11 ! interface GigabitEthernet0/1 ! interface GigabitEthernet0/1/0 ip address 10.1.12.1 255.255.255.0 ip ospf 1 area 11 ! router ospf 1 router-id 1.1.1.1

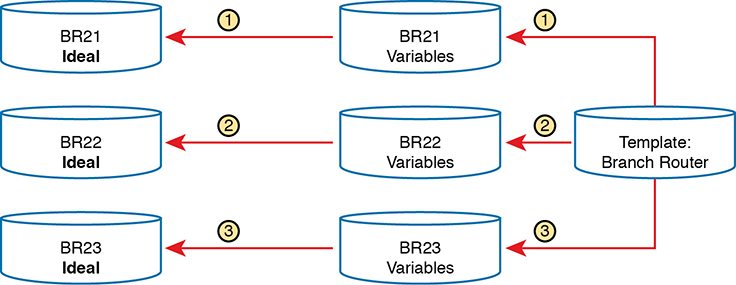

Configuration management tools can separate the components of a configuration into the parts in common to all devices in that role (the template) versus the parts unique to any one device (the variables). Engineers can then edit the standard template file for a device role as a separate file than each device’s variable file. The configuration management tool can then process the template and variables to create the ideal configuration file for each device, as shown in Figure 19-6, which shows the configuration files being built for branch routers BR21, BR22, and BR23.

Figure 19-6 Concept: Configuration Templates and Variables

To give a little more insight, Example 19-2 shows a template file that could be used by Ansible for the configuration shown in Example 19-1. Each tool specifies what language to use for each type of file, with Ansible using the Jinja2 language for templates. The template mimics the configuration in Example 19-1, except for placing variable names inside sets of double curly brackets.

Example 19-2 Jinja2 Template with Variables Based on Example 19-1

hostname {{hostname}} ! interface GigabitEthernet0/0 ip address {{address1}} {{mask1}} ip ospf {{OSPF_PID}} area {{area}} ! interface GigabitEthernet0/1 ! interface GigabitEthernet0/1/0 ip address {{address2}} {{mask2}} ip ospf {{OSPF_PID}} area {{area}} ! router ospf {{OSPF_PID}} router-id {{RID}}

To supply the values for a device, Ansible calls for defining variable files using YAML, as shown in Example 19-3. The file shows the syntax for defining the variables shown in the complete configuration in Example 19-1, but now defined as variables.

Example 19-3 YAML Variables File Based on Example 19-2

--- hostname: BR1 address1: 10.1.1.1 mask1: 255.255.255.0 address2: 10.1.12.1 mask2: 255.255.255.0 RID: 1.1.1.1 area: '11' OSPF_PID: '1'

The configuration management system processes a template plus all related variables to produce the intended configuration for a device. For instance, the engineer would create and edit one template file that looks like Example 19-2 and then create and edit one variable file like Example 19-3 for each branch office router. Ansible would process the files to create complete configuration files like the text shown in Example 19-1.

It might seem like extra work to separate configurations into a template and variables, but using templates has some big advantages. In particular:

Templates increase the focus on having a standard configuration for each device role, helping to avoid snowflakes (uniquely configured devices).

New devices with an existing role can be deployed easily by simply copying an existing per-device variable file and changing the values.

Templates allow for easier troubleshooting because troubleshooting issues with one standard template should find and fix issues with all devices that use the same template.

Tracking the file versions for the template versus the variables files allows for easier troubleshooting as well. Issues with a device can be investigated to find changes in the device’s settings separately from the standard configuration template.

Files That Control Configuration Automation

Configuration management tools also provide different methods to define logic and processes that tell the tool what changes to make, to which devices, and when. For instance, an engineer could direct a tool to make changes during a weekend change window. That same logic could specify a subset of the devices. It could also detail steps to verify the change before and after the change is attempted, and how to notify the engineers if an issue occurs.

Interestingly, you can do a lot of the logic without knowing how to program. Each tool uses a language of some kind that engineers use to define the action steps, often a language defined by that company (a domain-specific language). But they make the languages to be straightforward, and they are generally mush easier to learn than programming languages. Configuration management tools also enable you to extend the action steps beyond what can be done in the toolset by using a general programming language. Figure 19-7 summarizes the files you could see in any of the configuration management tools.

Figure 19-7 Important Files Used by Configuration Management Tools

Ansible, Puppet, and Chef Basics

This chapter focuses on one exam topic that asks about the capabilities of three configuration management tools: Ansible, Puppet, and Chef. The first major section of the chapter describes the capabilities of all three (and other) configuration management tools. This second major section examines a few of the features of each tool, focusing on terminology and major capabilities.

Ansible, Puppet, and Chef are software packages. You can purchase each tool, with variations on which package. However, they all also have different free options that allow you to download and learn about the tools, although you might need to run a Linux guest because some of the tools do not run in a Windows OS.

As for the names, most people use the words Ansible, Puppet, and Chef to refer to the companies as well as their primary configuration management products. All three emerged as part of the transition from hardware-based servers to virtualized servers, which greatly increased the number of servers and created the need for software automation to create, configure, and remove VMs. All three produce one or more configuration management software products that have become synonymous with their companies in many ways. (This chapter follows that convention, for the most part ignoring exact product names, and referring to products and software simply as Ansible, Puppet, and Chef.)

Next, on to some details about each.

Ansible

To use Ansible (www.ansible.com), you need to install Ansible on some computer: Mac, Linux, or a Linux VM on a Windows host. You can use the free open-source version or use the paid Ansible Tower server version.

Once it is installed, you create several text files, such as the following:

Playbooks: These files provide actions and logic about what Ansible should do.

Inventory: These files provide device hostnames along with information about each device, like device roles, so Ansible can perform functions for subsets of the inventory

Templates: Using Jinja2 language, the templates represent a device’s configuration but with variables (see Example 19-2).

Variables: Using YAML, a file can list variables that Ansible will substitute into templates (see Example 19-3).

As far as how Ansible works for managing network devices, it uses an agentless architecture. That means Ansible does not rely on any code (agent) running on the network device. Instead, Ansible relies on features typical in network devices, namely SSH and/or NETCONF, to make changes and extract information. When using SSH, the Ansible control node actually makes changes to the device like any other SSH user would do, but doing the work with Ansible code, rather than with a human.

Ansible can be described as using a push model (per Figure 19-8) rather than a pull model (like Puppet and Chef). After installing Ansible, an engineer needs to create and edit all the various Ansible files, including an Ansible playbook. Then the engineer runs the playbook, which tells Ansible to perform the steps. Those steps can include configuring one or more devices per the various files (step 3), with the control node seen as pushing the configuration to the device.

Figure 19-8 Ansible Push Model

As with all the tools, Ansible can do both configuration provisioning (configuring devices after changes are made in the files) and configuration monitoring (checking to find out whether the device config matches the ideal configuration on the control node). However, Ansible’s architecture more naturally fits with configuration provisioning, as seen in the figure. To do configuration monitoring, Ansible uses logic modules that detect and list configuration differences, after which the playbook defines what action to take (reconfigure or notify).

Puppet

To use Puppet (www.puppet.com), like Ansible, begin by installing Puppet on a Linux host. You can install it on your own Linux host, but for production purposes, you will normally install it on a Linux server called a Puppet master. As with Ansible, you can use a free open-source version with paid versions available. You can get started learning Puppet without a separate server for learning and testing.

Once installed, Puppet also uses several important text files with different components, such as the following:

Manifest: This is a human-readable text file on the Puppet master, using a language defined by Puppet, used to define the desired configuration state of a device.

Resource, Class, Module: These terms refer to components of the manifest, with the largest component (module) being composed of smaller classes, which are in turn composed of resources.

Templates: Using a Puppet domain-specific language, these files allow Puppet to generate manifests (and modules, classes, and resources) by substituting variables into the template.

One way to think about the differences between Ansible’s versus Puppet’s approach is that Ansible’s playbooks use an imperative language, whereas Puppet uses a declarative language. For instance, with Ansible, the playbook will list tasks and choices based on those results, like “Configure all branch routers in these locations, and if errors occur for any device, do these extra tasks for that device.” Puppet manifests instead declare the end state that a device should have: “This branch router should have the configuration in this file by the end of the process.” The manifest, built by the engineer, defines the end state, and Puppet has the job to cause the device to have that configuration, without being told the specific set of steps to take.

Puppet typically uses an agent-based architecture for network device support. Some network devices enable Puppet support via an on-device agent—think of it as another feature configurable on the device. However, not every Cisco OS supports Puppet agents, so Puppet solves that problem using a proxy agent running on some external host (called agentless operation). The external agent then uses SSH to communicate with the network device, as shown in Figure 19-9.

Figure 19-9 Agent-based and Agentless Operation for Puppet

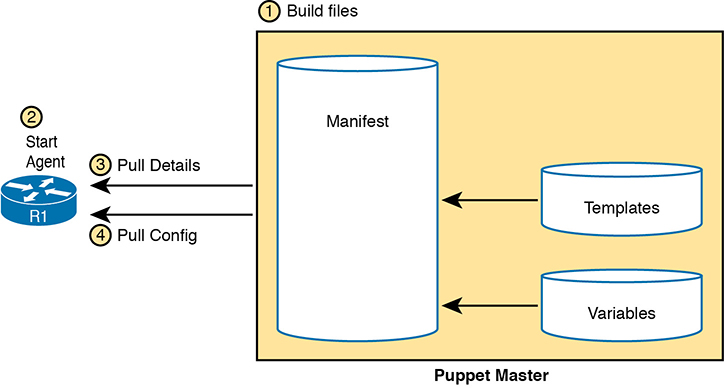

Armed with a manifest that declares something like “This device should have this configuration state,” Puppet uses a pull model to make that configuration appear in the device, as shown in Figure 19-10. Once installed, these steps occur:

Step 1. The engineer creates and edits all the files on the Puppet server.

Step 2. The engineer configures and enables the on-device agent or a proxy agent for each device.

Step 3. The agent pulls manifest details from the server, which tells the agent what its configuration should be.

Step 4. If the agent device’s configuration should be updated, the Puppet agent performs additional pulls to get all required detail, with the agent updating the device configuration.

Figure 19-10 Pull Model with Puppet

Chef

Chef (www.chef.io), as with Ansible and Puppet, exists as software packages you install and run. Chef (the company) offers several products, with Chef Automate being the product that most people refer to simply as Chef. As with Puppet, in production you probably run Chef as a server (called server-client mode), with multiple Chef workstations used by the engineering staff to build Chef files that are stored on the Chef server. However, you can also run Chef in standalone mode (called Chef Zero), which is helpful when you’re just getting started and learning in the lab.

Once Chef is installed, you create several text files with different components, like the following:

Resource: The configuration objects whose state is managed by Chef; for instance, a set of configuration commands for a network device—analogous to the ingredients in a recipe in a cookbook

Recipe: The Chef logic applied to resources to determine when, how, and whether to act against the resources—analogous to a recipe in a cookbook

Cookbooks: A set of recipes about the same kinds of work, grouped together for easier management and sharing

Runlist: An ordered list of recipes that should be run against a given device

Chef uses an architecture similar to Puppet. For network devices, each managed device (called a Chef node or Chef client) runs an agent. The agent performs configuration monitoring in that the client pulls recipes and resources from the Chef server and then adjusts its configuration to stay in sync with the details in those recipes and runlists. Note however that Chef requires on-device Chef client code, and many Cisco devices do not support a Chef client, so you will likely see more use of Ansible and Puppet for Cisco device configuration management.

Summary of Configuration Management Tools

All three of the configuration management tools listed here have a good base of users and different strengths. As for their use for managing network device configuration, Ansible appears to have the most interest, then Puppet, and then Chef. Ansible’s agentless architecture and the use of SSH provides support for a wide range of Cisco devices. Puppet’s agentless model also creates wide support for Cisco devices.

Table 19-2 summarizes a few of the most common ideas about each of the three automated configuration management tools. Note that the column for Puppet assumes an on-device agent.

Table 19-2 Comparing Ansible, Puppet, and Chef

Action |

Ansible |

Puppet |

Chef |

Term for the file that lists actions |

Playbook |

Manifest |

Recipe, Runlist |

Protocol to network device |

SSH, NETCONF |

HTTP (REST) |

HTTP (REST) |

Uses agent or agentless model |

Agentless |

Agent* |

Agent |

Push or pull model |

Push |

Pull |

Pull |

* Puppet can use an in-device agent or an external proxy agent for network devices. |

|||

Chapter Review

One key to doing well on the exams is to perform repetitive spaced review sessions. Review this chapter’s material using either the tools in the book or interactive tools for the same material found on the book’s companion website. Refer to the “Your Study Plan” element for more details. Table 19-3 outlines the key review elements and where you can find them. To better track your study progress, record when you completed these activities in the second column.

Table 19-3 Chapter Review Tracking

Review Element |

Review Date(s) |

Resource Used |

Review key topics |

|

Book, website |

Review key terms |

|

Book, website |

Repeat DIKTA questions |

|

Book, PTP |

Review memory table |

|

Book, website |

Do DevNet Labs |

|

DevNet |

Review All the Key Topics

Table 19-4 Key Topics for Chapter 19

Key Topic Element |

Description |

Page Number |

List |

Issues that arise from configuration drift |

|

Sample of showing router configuration file differences with GitHub |

||

Basic configuration monitoring concepts. |

||

List |

Primary functions of a configuration management tool |

|

Sample Jinja2 Ansible template |

||

List |

Advantages of using configuration templates |

|

Ansible’s push model and other features |

||

Puppet’s pull model and other features |

||

Summary of configuration management features and terms |

Key Terms You Should Know

Do DevNet Labs

Cisco’s DevNet site (https://developer.cisco.com)—a free site—includes lab environments and exercises. You can learn a lot about configuration management and Ansible in particular with a few of the lab tracks on the DevNet site (at the time this book was published). Refer to the “Chapter Review” section of the companion website for links to some good labs, or just go to https://developer.cisco.com and search for learning labs about Ansible.