CHAPTER 9

Legal, Regulations, Investigations, and Compliance

This chapter presents the following:

• Computer crime types

• Motives and profiles of attackers

• Various types of evidence

• Laws and acts put into effect to fight computer crime

• Computer crime investigation process and evidence collection

• Incident-handling procedures

• Ethics pertaining to information security and best practices

Computer and associated information crimes are the natural response of criminals to society’s increasing use of, and dependence upon, technology. For example, stalking can now take place in the virtual world with stalkers pursuing victims through social web sites or chat rooms. However, crime has always taken place, with or without a computer. A computer is just another tool and, like other tools before it, it can be used for good or evil.

Fraud, theft, and embezzlement have always been part of life, but the computer age has brought new opportunities for thieves and crooks. Organized crime can take advantage of the Internet to exploit people through phishing attacks, 419 scams (also called Nigerian Letter scams), and financial dealings. Digital storage and processing have been added to accounting, recordkeeping, communications, and funds transfer. This degree of complexity brings along its own set of vulnerabilities, which many crooks are all too eager to take advantage of.

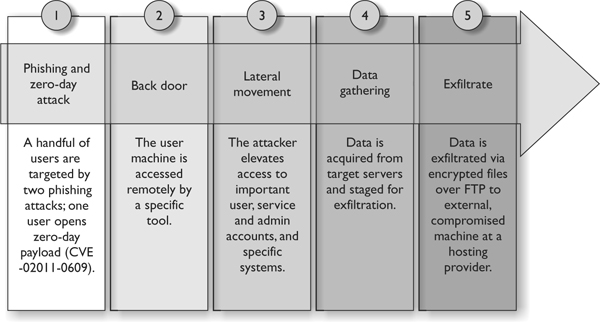

Companies are being blackmailed by cybercriminals who discover vulnerabilities in their networks. Company trade secrets and confidential information are being stolen when security breaches take place. Online banks are seeing a rise in fraud, and retailers’ databases are being attacked and robbed of their credit card information. In addition, identity theft is the fastest growing white-collar crime as of the writing of this book.

As e-commerce and online business become enmeshed in today’s business world, these types of issues become more important and more dangerous. Hacking and attacks are continually on the rise, and companies are well aware of it. The legal system and law enforcement are behind in their efforts to track down cybercriminals and successfully prosecute them (although they are getting better each year). New technologies to fight many types of attacks are on the way, but a great need still exists for proper laws, policies, and methods in actually catching the perpetrators and making them pay for the damage they cause. This chapter looks at some of these issues.

The Many Facets of Cyberlaw

Legal issues are very important to companies because a violation of legal commitments can be damaging to a company’s bottom line and its reputation. A company has many ethical and legal responsibilities it is liable for in regard to computer fraud. The more knowledge one has about these responsibilities, the easier it is to stay within the proper boundaries.

These issues may fall under laws and regulations pertaining to incident handling; privacy protection; computer abuse; control of evidence; or the ethical conduct expected of companies, their management, and their employees. This is an interesting time for law and technology because technology is changing at an exponential rate. Legislators, judges, law enforcement, and lawyers are behind the eight ball because of their inability to keep up with technological changes in the computing world and the complexity of the issues involved. Law enforcement needs to know how to capture a cybercriminal, properly seize and control evidence, and hand that evidence over to the prosecutorial and defense teams. Both teams must understand what actually took place in a computer crime, how it was carried out, and what legal precedents to use to prove their points in court. Many times, judges and juries are confused by the technology, terms, and concepts used in these types of trials, and laws are not written fast enough to properly punish the guilty cybercriminals. Law enforcement, the court system, and the legal community are definitely experiencing growth pains as they are being pulled into the technology of the 21st century.

Many companies are doing business across state lines and in different countries. This brings even more challenges when it comes to who has to follow what laws. Different states can interpret the same law differently, or they have their own set of laws. One country may not consider a particular action against the law at all, whereas another country may determine that the same action demands five years in prison. One of the complexities in these issues is jurisdiction. If a hacker from another country steals a bunch of credit card numbers from a U.S. financial institution and he is caught, a U.S. court would want to prosecute him. His homeland may not see this issue as illegal at all or have laws restricting such activities. Although the attackers are not restricted or hampered by country borders, the laws are restricted to borders in many cases.

Despite all of this confusion, companies do have some clear-cut responsibilities pertaining to computer security issues and specifics on how companies are expected to prevent, detect, and report crimes.

The Crux of Computer Crime Laws

Computer crime laws (sometimes referred to as cyberlaw) around the world deal with some of the core issues: unauthorized modification or destruction, disclosure of sensitive information, unauthorized access, and the use of malware (malicious software).

Although we usually only think of the victims and their systems that were attacked during a crime, laws have been created to combat three categories of crimes. A computer-assisted crime is where a computer was used as a tool to help carry out a crime. A computer-targeted crime concerns incidents where a computer was the victim of an attack crafted to harm it (and its owners) specifically. The last type of crime is where a computer is not necessarily the attacker or the attackee, but just happened to be involved when a crime was carried out. This category is referred to as computer is incidental.

Some examples of computer-assisted crimes are

• Attacking financial systems to carry out theft of funds and/or sensitive information

• Obtaining military and intelligence material by attacking military systems

• Carrying out industrial spying by attacking competitors and gathering confidential business data

• Carrying out information warfare activities by attacking critical national infrastructure systems

• Carrying out hactivism, which is protesting a government or company’s activities by attacking their systems and/or defacing their web sites.

Some examples of computer-targeted crimes include

• Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks

• Capturing passwords or other sensitive data

• Installing malware with the intent to cause destruction

• Installing rootkits and sniffers for malicious purposes

• Carrying out a buffer overflow to take control of a system

NOTE The main issues addressed in computer crime laws are unauthorized modification, disclosure, destruction, or access and inserting malicious programming code.

NOTE The main issues addressed in computer crime laws are unauthorized modification, disclosure, destruction, or access and inserting malicious programming code.

Some confusion typically exists between the two categories—computer-assisted crimes and computer-targeted crimes—because intuitively it would seem any attack would fall into both of these categories. One system is carrying out the attacking, while the other system is being attacked. The difference is that in computer-assisted crimes, the computer is only being used as a tool to carry out a traditional type of crime. Without computers, people still steal, cause destruction, protest against companies (for example, companies that carry out experiments upon animals), obtain competitor information, and go to war. So these crimes would take place anyway; it is just that the computer is simply one of the tools available to the evildoer. As such, it helps the evildoer become more efficient at carrying out a crime. Computer-assisted crimes are usually covered by regular criminal laws in that they are not always considered a “computer crime.” One way to look at it is that a computer-targeted crime could not take place without a computer, whereas a computer-assisted crime could. Thus, a computer-targeted crime is one that did not, and could not, exist before computers became of common use. In other words, in the good old days, you could not carry out a buffer overflow on your neighbor, or install malware on your enemy’s system. These crimes require that computers be involved.

If a crime falls into the “computer is incidental” category, this means a computer just happened to be involved in some secondary manner, but its involvement is still significant. For example, if you had a friend who worked for a company that runs the state lottery and he gives you a printout of the next three winning numbers and you type them into your computer, your computer is just the storage place. You could have just kept the piece of paper and not put the data in a computer. Another example is child pornography. The actual crime is obtaining and sharing child pornography pictures or graphics. The pictures could be stored on a file server or they could be kept in a physical file in someone’s desk. So if a crime falls within this category, the computer is not attacking another computer, and a computer is not being attacked, but the computer is still used in some significant manner.

You may say, “So what? A crime is a crime. Why break it down into these types of categories?” The reason these types of categories are created is to allow current laws to apply to these types of crimes, even though they are in the digital world. Let’s say someone is on your computer just looking around, not causing any damage, but she should not be there. Should the legislation have to create a new law stating, “Thou shall not browse around in someone else’s computer,” or should we just use the already created trespassing law? What if a hacker got into a system that made all of the traffic lights turn green at the exact same time? Should the government go through the hassle of creating a new law for this type of activity, or should the courts use the already created (and understood) manslaughter and murder laws? Remember, a crime is a crime, and a computer is just a new tool to carry out traditional criminal activities.

By allowing the use of current laws, this makes it easier for a judge to know what the proper sentencing (punishments) are for these specific crimes. Sentencing guidelines have been developed by governments to standardize punishments for the same types of crimes throughout federal courts. To use a simplistic description, the guidelines utilize a point system. For example, if you kidnap someone, you receive 10 points. If you take that person over state boundary lines, you get another 2 points. If you hurt this person, you get another 4 points. The higher the points, the more severe the punishment.

So if you steal money from someone’s financial account by attacking a bank’s mainframe, you may get 5 points. If you use this money to support a terrorist group, you get another 5 points. If you do not claim this revenue on your tax returns, there will be no points. The IRS just takes you behind a building and shoots you in the head.

Now, this in no way means countries can just depend upon the laws on the books and that every computer crime can be countered by an existing law. Many countries have had to come up with new laws that deal specifically with different types of computer crimes. For example, the following are just some of the laws that have been created or modified in the United States to cover the various types of computer crimes:

• 18 USC 1029: Fraud and Related Activity in Connection with Access Devices

• 18 USC 1030: Fraud and Related Activity in Connection with Computers

• 18 USC 2510 et seq.: Wire and Electronic Communications Interception and Interception of Oral Communications

• 18 USC 2701 et seq.: Stored Wire and Electronic Communications and Transactional Records Access

• Digital Millennium Copyright Act

• Cyber Security Enhancement Act of 2002

NOTE You do not need to know these laws for the CISSP exam; they are just examples.

NOTE You do not need to know these laws for the CISSP exam; they are just examples.

Complexities in Cybercrime

Who did what, to whom, where, and how?

Response: I have no idea.

Since we have a bunch of laws to get the digital bad guys, this means we have this whole cybercrime thing under control, right?

Alas, hacking, cracking, and attacking have only increased over the years and will not stop anytime soon. Several issues deal with why these activities have not been properly stopped or even curbed. These include proper identification of the attackers, the necessary level of protection for networks, and successful prosecution once an attacker is captured.

Most attackers are never caught because they spoof their addresses and identities and use methods to cover their footsteps. Many attackers break into networks, take whatever resources they were after, and clean the logs that tracked their movements and activities. Because of this, many companies do not even know they have been violated. Even if an attacker’s activities trigger an intrusion detection system (IDS) alert, it does not usually find the true identity of the individual, though it does alert the company that a specific vulnerability was exploited.

Attackers commonly hop through several systems before attacking their victim so that tracking them down will be more difficult. Many of these criminals use innocent people’s computers to carry out the crimes for them. The attacker will install malicious software on a computer using many types of methods: e-mail attachments, a user downloading a Trojan horse from a web site, exploiting a vulnerability, and so on. Once the software is loaded, it stays dormant until the attacker tells it what systems to attack and when. These compromised systems are called zombies, the software installed on them are called bots, and when an attacker has several compromised systems, this is known as a botnet. The botnet can be used to carry out DDoS attacks, transfer spam or pornography, or do whatever the attacker programs the bot software to do. These items are covered more in depth in Chapter 10, but are discussed here to illustrate how attackers easily hide their identity.

Within the United States, local law enforcement departments, the FBI, and the Secret Service are called upon to investigate a range of computer crimes. Although each of these entities works to train its people to identify and track computer criminals, collectively they are very far behind the times in their skills and tools, and are outnumbered by the number of hackers actively attacking networks. Because the attackers use tools that are automated, they can perform several serious attacks in a short timeframe. When law enforcement is called in, its efforts are usually more manual—checking logs, interviewing people, investigating hard drives, scanning for vulnerabilities, and setting up traps in case the attacker comes back. Each agency can spare only a small number of people for computer crimes, and generally they are behind in their expertise compared to many hackers. Because of this, most attackers are never found, much less prosecuted.

This in no way means all attackers get away with their misdeeds. Law enforcement is continually improving its tactics, and individuals are being prosecuted every month. The following site shows all of the current and past prosecutions that have taken place in the United States: www.cybercrime.gov. The point is that this is still a small percentage of people who are carrying out digital crimes.

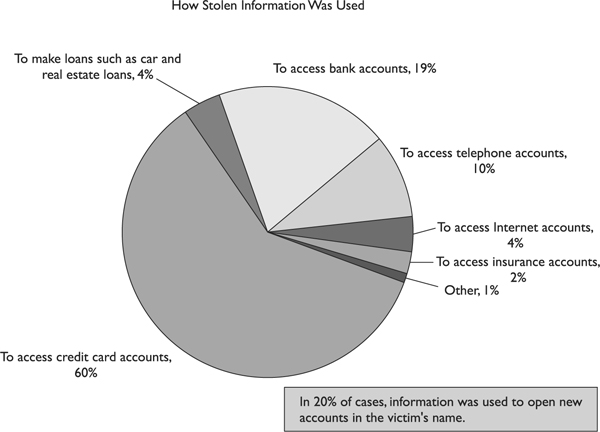

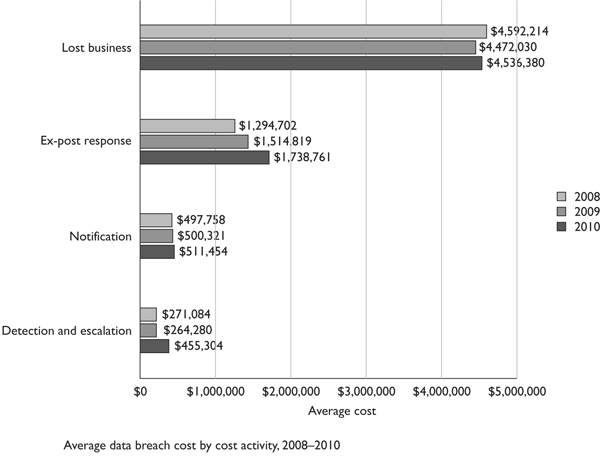

Really only a handful of laws deal specifically with computer crimes, making it more challenging to successfully prosecute the attackers who are caught. Many companies that are victims of an attack usually just want to ensure that the vulnerability the attacker exploited is fixed, instead of spending the time and money to go after and prosecute the attacker. (Most common approaches to breaches are shown in Figure 9-1.) This is a huge contributing factor as to why cybercriminals get away with their activities. Some regulated organizations—for instance, financial institutions—by law, must report breaches. However, most organizations do not have to report breaches or computer crimes. No company wants their dirty laundry out in the open for everyone to see. The customer base will lose confidence, as will the shareholders and investors. We do not actually have true computer crime statistics because most are not reported.

Figure 9-1 Common approaches to security breaches

Although regulations, laws, and attacks help make senior management more aware of security issues, when their company ends up in the headlines and it’s told how they lost control of over 100,000 credit card numbers, security suddenly becomes very important to them.

CAUTION Even though financial institutions must, by law, report security breaches and crimes, that does not mean they all follow this law. Some of these institutions, just like many other organizations, often simply fix the vulnerability and sweep the details of the attack under the carpet.

CAUTION Even though financial institutions must, by law, report security breaches and crimes, that does not mean they all follow this law. Some of these institutions, just like many other organizations, often simply fix the vulnerability and sweep the details of the attack under the carpet.

Electronic Assets

Another complexity that the digital world has brought upon society is defining what has to be protected and to what extent. We have gone through a shift in the business world pertaining to assets that need to be protected. Fifteen years ago and more, the assets that most companies concerned themselves with protecting were tangible ones (equipment, building, manufacturing tools, inventory). Now companies must add data to their list of assets, and data are usually at the very top of that list: product blueprints, Social Security numbers, medical information, credit card numbers, personal information, trade secrets, military deployment and strategies, and so on. Although the military has always had to worry about keeping their secrets secret, they have never had so many entry points to the secrets that had to be controlled. Companies are still having a hard time not only protecting their data in digital format, but defining what constitutes sensitive data and where that data should be kept.

NOTE In many countries, to deal more effectively with computer crime, legislative bodies have broadened the definition of property to include data.

NOTE In many countries, to deal more effectively with computer crime, legislative bodies have broadened the definition of property to include data.

As many companies have discovered, protecting intangible assets (i.e., data, reputation) is much more difficult than protecting tangible assets.

The Evolution of Attacks

We have gone from bored teenagers with too much time on their hands to organized crime rings with very defined targets and goals.

About ten years ago, and even further back, hackers were mainly made up of people who just enjoyed the thrill of hacking. It was seen as a challenging game without any real intent of harm. Hackers used to take down large web sites (Yahoo!, MSN, Excite) so their activities made the headlines and they won bragging rights among their fellow hackers. Back then, virus writers created viruses that simply replicated or carried out some benign activity, instead of the more malicious actions they could have carried out. Unfortunately, today, these trends have taken on more sinister objectives.

Although we still have script kiddies and people who are just hacking for the fun of it, organized criminals have appeared on the scene and really turned up the heat regarding the amount of damage done. In the past, script kiddies would scan thousands and thousands of systems looking for a specific vulnerability so they could exploit it. It did not matter if the system was on a company network, a government system, or a home user system. The attacker just wanted to exploit the vulnerability and “play” on the system and network from there. Today’s attackers are not so noisy, however, and they certainly don’t want any attention drawn to themselves. These organized criminals are after specific targets for specific reasons, usually profit-oriented. They try and stay under the radar and capture credit card numbers, Social Security numbers, and personal information to carry out fraud and identity theft.

NOTE Script kiddies are hackers who do not necessarily have the skill to carry out specific attacks without the tools provided for them on the Internet and through friends. Since these people do not necessarily understand how the attacks are actually carried out, they most likely do not understand the extent of damage they can cause.

NOTE Script kiddies are hackers who do not necessarily have the skill to carry out specific attacks without the tools provided for them on the Internet and through friends. Since these people do not necessarily understand how the attacks are actually carried out, they most likely do not understand the extent of damage they can cause.

Many times hackers are just scanning systems looking for a vulnerable running service or sending out malicious links in emails to unsuspecting victims. They are just looking for any way to get into any network. This would be the shotgun approach to network attacks. Another, more dangerous attacker has you in his crosshairs and he is determined to identify your weakest point and do with you what he will.

As an analogy, the thief that goes around rattling door knobs to find one that is not locked is not half as dangerous as the one who will watch you day in and day out to learn your activity patterns, where you work, what type of car you drive, who your family is, and patiently wait for your most vulnerable moment to ensure a successful and devastating attack.

In the computing world, we call this second type of attacker an advanced persistent threat (APT). This is a military term that has been around for ages, but since the digital world is becoming more of a battleground, this term is more relevant each and every day. How APTs differ from the regular old vanilla attacker is that it is commonly a group of attackers, not just one hacker, who combines knowledge and abilities to carry out whatever exploit that will get them into the environment they are seeking. The APT is very focused and motivated to aggressively and successfully penetrate a network with variously different attack methods and then clandestinely hide its presence while achieving a well-developed, multilevel foothold in the environment. The “advanced” aspect of this term pertains to the expansive knowledge, capabilities, and skill base of the APT. The “persistent” component has to do with the fact that the attacker is not in a hurry to launch and attack quickly, but will wait for the most beneficial moment and attack vector to ensure that its activities go unnoticed. This is what we refer to as a “low-and-slow” attack. This type of attack is coordinated by human involvement, rather than just a virus-type of threat that goes through automated steps to inject its payload. The APT has specific objectives and goals and is commonly highly organized and well-funded, which makes it the biggest threat of all.

An APT is commonly custom-developed malicious code that is built specifically for its target, has multiple ways of hiding itself once it infiltrates the environment, may be able to polymorph itself in replication capabilities, and has several different “anchors” so eradicating it is difficult if it is discovered. Once the code is installed, it commonly sets up a covert back channel (as regular bots do) so that it can be remotely controlled by the attacker himself. The remote control functionality allows the attacker to transverse the network with the goal of gaining continuous access to critical assets.

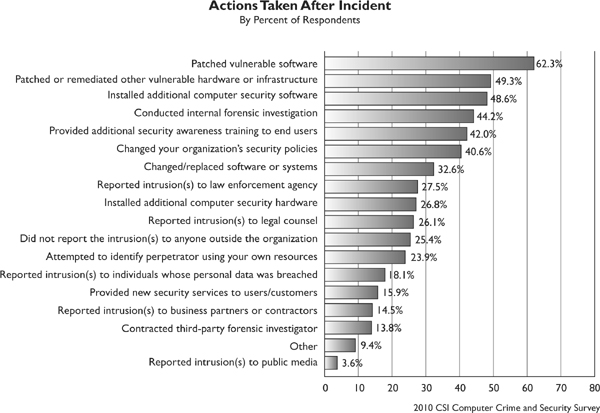

APT infiltrations are usually very hard to detect with host-based solutions because the attacker puts the code through a barrage of tests against the most up-to-date detection applications on the market. A common way to detect these types of threats is through network traffic changes. When there is a new IRC connection from a host, that is a good indication that the system has a bot communicating to its command center. Since several technologies are used in environments today to detect just that type of traffic, the APT may have multiple control centers to communicate with so that if one connection gets detected and removed it still has an active channel to use. The APT may implement some type of virtual private network (VPN) connection so that its data that is in transmission cannot be inspected. Figure 9-2 illustrates the common steps and results of APT activity.

Figure 9-2 Gaining access into an environment and extracting sensitive data

The ways of getting into a network are basically endless (exploit a web service, e-mail links and attachments to users, gain access through remote maintenance accounts, exploit operating systems and application vulnerabilities, compromise connections from home users, etc.). Each of these vulnerabilities has their own fixes (patches, proper configuration, awareness, proper credential practices, encryption, etc.). It is not only these fixes that need to be put in place; we need to move to a more effective situational awareness model. We need to have better capabilities of what is happening throughout our network in near to real time so that our defenses can react quickly and precisely.

Our battlefield landscape is changing from “smash-and-grab” attacks to “slow-and-determined” attacks. Just like military offensive practices evolve and morph as the target does the same, so must we as an industry.

We have already seen a decrease in the amount of viruses created just to populate as many systems as possible, and it is predicted that this benign malware activity will continue to decrease, while more dangerous malware increases. This more dangerous malware has more focused targets and more powerful payloads—usually installing back doors, bots, and/or loading rootkits.

So while the sophistication of the attacks continues to increase, so does the danger of these attacks. Isn’t that just peachy?

Up until now, we have listed some difficulties of fighting cybercrime: the anonymity the Internet provides the attacker; attackers are organizing and carrying out more sophisticated attacks; the legal system is running to catch up with these types of crimes; and companies are just now viewing their data as something that must be protected. All these complexities aid the bad guys, but what if we throw in the complexity of attacks taking place between different countries?

International Issues

If a hacker in Ukraine attacked a bank in France, whose legal jurisdiction is that? How do these countries work together to identify the criminal and carry out justice? Which country is required to track down the criminal? And which country should take this person to court? Well, we don’t really know exactly. We are still working this stuff out.

When computer crime crosses international boundaries, the complexity of such issues shoots up exponentially and the chances of the criminal being brought to any court decreases. This is because different countries have different legal systems, some countries have no laws pertaining to computer crime, jurisdiction disputes may erupt, and some governments may not want to play nice with each other. For example, if someone in Iran attacked a system in Israel, do you think the Iranian government would help Israel track down the attacker? What if someone in North Korea attacked a military system in the United States? Do you think these two countries would work together to find the hacker? Maybe or maybe not—or perhaps the attack was carried out by their specific government.

There have been efforts to standardize the different countries’ approach to computer crimes because they happen so easily over international boundaries. Although it is very easy for an attacker in China to send packets through the Internet to a bank in Saudi Arabia, it is very difficult (because of legal systems, cultures, and politics) to motivate these governments to work together.

The Council of Europe (CoE) Convention on Cybercrime is one example of an attempt to create a standard international response to cybercrime. In fact, it is the first international treaty seeking to address computer crimes by coordinating national laws and improving investigative techniques and international cooperation. The convention’s objectives include the creation of a framework for establishing jurisdiction and extradition of the accused. For example, extradition can only take place when the event is a crime in both jurisdictions.

Many companies communicate internationally every day through email, telephone lines, satellites, fiber cables, and long-distance wireless transmission. It is important for a company to research the laws of different countries pertaining to information flow and privacy.

Global organizations that move data across other country boundaries must be aware of and follow the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data rules. Since most countries have a different set of laws pertaining to the definition of private data and how it should be protected, international trade and business get more convoluted and can negatively affect the economy of nations. The OECD is an international organization that helps different governments come together and tackle the economic, social, and governance challenges of a globalized economy. Because of this, the OECD came up with guidelines for the various countries to follow so that data are properly protected and everyone follows the same type of rules.

The core principles defined by the OECD are as follows:

• Collection of personal data should be limited, obtained by lawful and fair means, and with the knowledge of the subject.

• Personal data should be kept complete and current, and be relevant to the purposes for which it is being used.

• Subjects should be notified of the reason for the collection of their personal information at the time that it is collected, and organizations should only use it for that stated purpose.

• Only with the consent of the subject or by the authority of law should personal data be disclosed, made available, or used for purposes other than those previously stated.

• Reasonable safeguards should be put in place to protect personal data against risks such as loss, unauthorized access, modification, and disclosure.

• Developments, practices, and policies regarding personal data should be openly communicated. In addition, subjects should be able to easily establish the existence and nature of personal data, its use, and the identity and usual residence of the organization in possession of that data.

• Subjects should be able to find out whether an organization has their personal information and what that information is, to correct erroneous data, and to challenge denied requests to do so.

• Organizations should be accountable for complying with measures that support the previous principles.

NOTE Information on OECD Guidelines can be found at www.oecd.org/document/18/0,2340,en_2649_34255_1815186_1_1_1_1,00.html.

NOTE Information on OECD Guidelines can be found at www.oecd.org/document/18/0,2340,en_2649_34255_1815186_1_1_1_1,00.html.

Although the OECD is a great start, we still have a long way to go to standardize how cybercrime is dealt with internationally.

Organizations that are not aware of and/or do not follow these types of rules and guidelines can be fined and found criminally negligent, their business can be disrupted, or they can go out of business. If your company is expecting to expand globally, it would be wise to have legal counsel that understands these types of issues so this type of trouble does not find its way to your company’s doorstep.

The European Union (EU) in many cases takes individual privacy much more seriously than most other countries in the world, so they have strict laws pertaining to data that are considered private, which are based on the European Union Principles on Privacy. This set of principles addresses using and transmitting information considered private in nature. The principles and how they are to be followed are encompassed within the EU’s Data Protection Directive. All states in Europe must abide by these principles to be in compliance, and any company wanting to do business with an EU company, which will include exchanging privacy type of data, must comply with this directive.

A construct that outlines how U.S.-based companies can comply with the EU privacy principles has been developed, which is called the Safe Harbor Privacy Principles. If a non-European organization wants to do business with a European entity, it will need to adhere to the Safe Harbor requirements if certain types of data will be passed back and forth during business processes. Europe has always had tighter control over protecting privacy information than the United States and other parts of the world. So in the past when U.S. and European companies needed to exchange data, confusion erupted and business was interrupted because the lawyers had to get involved to figure out how to work within the structures of the differing laws. To clear up this mess, a “safe harbor” framework was created, which outlines how any entity that is going to move privacy data to and from Europe must go about protecting it. U.S. companies that deal with European entities can become certified against this rule base so data transfer can happen more quickly and easily. The privacy data protection rules that must be met to be considered “Safe Harbor” compliant are listed here:

• Notice Individuals must be informed that their data is being collected and about how it will be used.

• Choice Individuals must have the ability to opt out of the collection and forward transfer of the data to third parties.

• Onward Transfer Transfers of data to third parties may only occur to other organizations that follow adequate data protection principles.

• Security Reasonable efforts must be made to prevent loss of collected information.

• Data Integrity Data must be relevant and reliable for the purpose it was collected for.

• Access Individuals must be able to access information held about them, and correct or delete it if it is inaccurate.

• Enforcement There must be effective means of enforcing these rules.

Import/Export Legal Requirements

Another complexity that comes into play when an organization is attempting to work with organizations in other parts of the world is import and export laws. Each country has its own specifications when it comes to what is allowed in their borders and what is allowed out. For example, the Wassenaar Arrangement implements export controls for “Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies.” It is currently made up of 40 countries and lays out rules on how the following items can be exported from country to country:

• Category 1 Special Materials and Related Equipment

• Category 2 Materials Processing

• Category 3 Electronics

• Category 4 Computers

• Category 5 Part 1: Telecommunications

• Category 5 Part 2: “Information Security”

• Category 6 Sensors and “Lasers”

• Category 7 Navigation and Avionics

• Category 8 Marine

• Category 9 Aerospace and Propulsion

The main goal of this arrangement is to prevent the buildup of military capabilities that could threaten regional and international security and stability. So everyone is keeping an eye on each other to make sure no one country’s weapons can take everyone else out. The idea is to try and make sure everyone has similar military offense and defense capabilities with the hope that we won’t end up blowing each other up.

One item the agreement deals with is cryptography, which is seen as a dual-use good. It can be used for military and civilian uses. It is seen to be dangerous to export products with cryptographic functionality to countries that are in the “offensive” column, meaning that they are thought to have friendly ties with terrorist organizations and/or want to take over the world through the use of weapons of mass destruction. If the “good” countries allow the “bad” countries to use cryptography, then the “good” countries cannot snoop and keep tabs on what the “bad” countries are up to.

The specifications of the Wassenaar Arrangement are complex and always changing. The countries that fall within the “good” and “bad” categories change and what can be exported to who and how changes. In some cases, no products that contain cryptographic functions can be exported to a specific country, a different country could be allowed products with limited cryptographic functions, some countries require certain licenses to be granted, and then other countries (the “good” countries) have no restrictions.

While the Wassenaar Arrangement deals mainly with the exportation of items, some countries (China, Russia, Iran, Iraq, etc.) have cryptographic import restrictions that have to be understood and followed. These countries do not allow their citizens to use cryptography because they follow the Big Brother approach to governing people.

This obviously gets very complex for companies who sell products that use integrated cryptographic functionality. One version of the product may be sold to China, if it has no cryptographic functionality. Another version may be sold to Russia, if a certain international license is in place. A full functioning product can be sold to Canada, because who are they ever going to hurt?

It is important to understand the import and export requirements your company must meet when interacting with entities in other parts of the world. You could be breaking a country’s law or an international treaty if you do not get the right type of lawyers involved in the beginning and follow the approved processes.

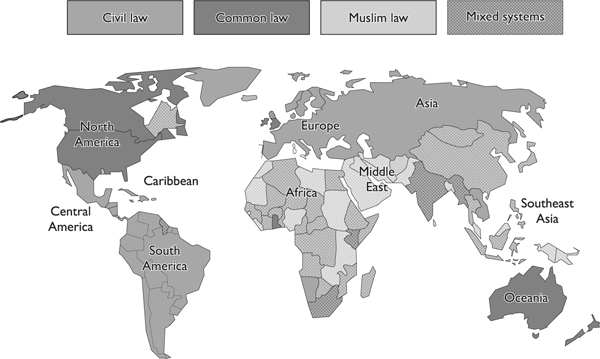

Types of Legal Systems

As stated earlier, different countries often have different legal systems. In this section, we will cover the core components of these systems and what differentiates them.

• Civil (Code) Law System

• System of law used in continental European countries such as France and Spain.

• Different legal system from the common law system used in the United Kingdom and United States.

• Civil law system is rule-based law not precedence based.

• For the most part, a civil law system is focused on codified law—or written laws.

• The history of the civil law system dates to the sixth century when the Byzantine emperor Justinian codified the laws of Rome.

• Civil legal systems should not be confused with the civil (or tort) laws found in the United States.

• The civil legal system was established by states or nations for self-regulation; thus, the civil law system can be divided into subdivisions, such as French civil law, German civil law, and so on.

• It is the most widespread legal system in the world and the most common legal system in Europe.

• Under the civil legal system, lower courts are not compelled to follow the decisions made by higher courts.

• Common Law System

• Developed in England.

• Based on previous interpretations of laws:

• In the past, judges would walk throughout the country enforcing laws and settling disputes.

• They did not have a written set of laws, so they based their laws on custom and precedent.

• In the 12th century, the King of England imposed a unified legal system that was “common” to the entire country.

• Reflects the community’s morals and expectations.

• Led to the creation of barristers, or lawyers, who actively participate in the litigation process through the presentation of evidence and arguments.

• Today, the common law system uses judges and juries of peers. If the jury trial is waived, the judge decides the facts.

• Typical systems consist of a higher court, several intermediate appellate courts, and many local trial courts. Precedent flows down through this system. Tradition also allows for “magistrate’s courts,” which address administrative decisions.

• The common law system is broken down into the following:

• Criminal.

• Based on common law, statutory law, or a combination of both.

• Addresses behavior that is considered harmful to society.

• Punishment usually involves a loss of freedom, such as incarceration, or monetary fines.

• Civil/tort

• Offshoot of criminal law.

• Under civil law, the defendant owes a legal duty to the victim. In other words, the defendant is obligated to conform to a particular standard of conduct, usually set by what a “reasonable man of ordinary prudence” would do to prevent foreseeable injury to the victim.

• The defendant’s breach of that duty causes injury to the victim; usually physical or financial.

• Categories of civil law:

• Intentional Examples include assault, intentional infliction of emotional distress, or false imprisonment.

• Wrongs against property An example is nuisance against landowner.

• Wrongs against a person Examples include car accidents, dog bites, and a slip and fall.

• Negligence An example is wrongful death.

• Nuisance An example is trespassing.

• Dignitary wrongs Include invasion of privacy and civil rights violations.

• Economic wrongs Examples include patent, copyright, and trademark infringement.

• Strict liability Examples include a failure to warn of risks and defects in product manufacturing or design.

• Administrative (regulatory)

• Laws and legal principles created by administrative agencies to address a number of areas, including international trade, manufacturing, environment, and immigration.

• Responsibility is on the prosecution to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt (innocent until proven guilty).

• Used in Canada, United Kingdom, Australia, United States, and New Zealand.

• Customary Law System

• Deals mainly with personal conduct and patterns of behavior.

• Based on traditions and customs of the region.

• Emerged when cooperation of individuals became necessary as communities merged.

• Not many countries work under a purely customary law system, but instead use a mixed system where customary law is an integrated component. (Codified civil law systems emerged from customary law.)

• Mainly used in regions of the world that have mixed legal systems (for example, China and India).

• Restitution is commonly in the form of a monetary fine or service.

• Religious Law System

• Based on religious beliefs of the region.

• In Islamic countries, the law is based on the rules of the Koran.

• The law, however, is different in every Islamic country.

• Jurists and clerics have a high degree of authority.

• Cover all aspects of human life, but commonly divided into:

• Responsibilities and obligations to others.

• Religious duties.

• Knowledge and rules as revealed by God, which define and govern human affairs.

• Rather than create laws, lawmakers and scholars attempt to discover the truth of law.

• Law, in the religious sense, also includes codes of ethics and morality, which are upheld and required by God. For example, Hindu law, Sharia (Islamic law), Halakha (Jewish law), and so on.

• Two or more legal systems are used together and apply cumulatively or interactively.

• Most often mixed law systems consist of civil and common law.

• A combination of systems is used as a result of more or less clearly defined fields of application.

• Civil law may apply to certain types of crimes, while religious law may apply to other types within the same region.

• Examples of mixed law systems include Holland, Canada, and South Africa.

These different legal systems are certainly complex and while you are not expected to be a lawyer to pass the CISSP exam, having a high-level understanding of the different types (civil, common, customary, religious, mixed) is important. The exam will dig more into the specifics of the common law legal system and its components. Under the common law legal system, civil law deals with wrongs against individuals or companies that result in damages or loss. This is referred to as tort law. Examples include trespassing, battery, negligence, and products liability. A civil lawsuit would result in financial restitution and/or community service instead of a jail sentence. When someone sues another person in civil court, the jury decides upon liability instead of innocence or guilt. If the jury determines the defendant is liable for the act, then the jury decides upon the punitive damages of the case.

Criminal law is used when an individual’s conduct violates the government laws, which have been developed to protect the public. Jail sentences are commonly the punishment for criminal law cases, whereas in civil law cases the punishment is usually an amount of money that the liable individual must pay the victim. For example, in the O.J. Simpson case, he was first tried and found not guilty in the criminal law case, but then was found liable in the civil law case. This seeming contradiction can happen because the burden of proof is lower in civil cases than in criminal cases.

NOTE Civil law generally is derived from common law (case law), cases are initiated by private parties, and the defendant is found liable or not liable for damages. Criminal law typically is statutory, cases are initiated by government prosecutors, and the defendant is found guilty or not guilty.

NOTE Civil law generally is derived from common law (case law), cases are initiated by private parties, and the defendant is found liable or not liable for damages. Criminal law typically is statutory, cases are initiated by government prosecutors, and the defendant is found guilty or not guilty.

Administrative/regulatory law deals with regulatory standards that regulate performance and conduct. Government agencies create these standards, which are usually applied to companies and individuals within those specific industries. Some examples of administrative laws could be that every building used for business must have a fire detection and suppression system, must have easily seen exit signs, and cannot have blocked doors, in case of a fire. Companies that produce and package food and drug products are regulated by many standards so the public is protected and aware of their actions. If a case was made that specific standards were not abided by, high officials in the companies could be held accountable, as in a company that makes tires that shred after a couple of years of use. The people who held high positions in this company were most likely aware of these conditions but chose to ignore them to keep profits up. Under administrative, criminal, and civil law, they may have to pay dearly for these decisions.

Intellectual Property Laws

I made it, it is mine, and I want to protect it.

Intellectual property laws do not necessarily look at who is right or wrong, but rather how a company or individual can protect what it rightfully owns from unauthorized duplication or use, and what it can do if these laws are violated.

A major issue in many intellectual property cases is what the company did to protect the resources it claims have been violated in one fashion or another. A company must go through many steps to protect resources that it claims to be intellectual property and must show that it exercised due care (reasonable acts of protection) in its efforts to protect those resources. If an employee sends a file to a friend and the company attempts to terminate the employee based on the activity of illegally sharing intellectual property, it must show the court why this file is so important to the company, what type of damage could be or has been caused as a result of the file being shared, and, most important, what the company had done to protect that file. If the company did not secure the file and tell its employees that they were not allowed to copy and share that file, then the company will most likely lose the case. However, if the company went through many steps to protect that file, explained to its employees that it was wrong to copy and share the information within the file, and that the punishment could be termination, then the company could not be charged with falsely terminating an employee.

Intellectual property can be protected by several different laws, depending upon the type of resource it is. Intellectual property is divided into two categories: industrial property—such as inventions (patents), industrial designs, and trademarks—and copyright, which covers things like literary and artistic works. These topics are addressed in depth in the following sections.

Trade Secret

I Googled Kentucky Fried Chicken’s recipes, but can’t find them.

Response: I wonder why.

Trade secret law protects certain types of information or resources from unauthorized use or disclosure. For a company to have its resource qualify as a trade secret, the resource must provide the company with some type of competitive value or advantage. A trade secret can be protected by law if developing it requires special skill, ingenuity, and/or expenditure of money and effort. This means that a company cannot say the sky is blue and call it a trade secret.

A trade secret is something that is proprietary to a company and important for its survival and profitability. An example of a trade secret is the formula used for a soft drink, such as Coke or Pepsi. The resource that is claimed to be a trade secret must be confidential and protected with certain security precautions and actions. A trade secret could also be a new form of mathematics, the source code of a program, a method of making the perfect jelly bean, or ingredients for a special secret sauce. A trade secret has no expiration date unless the information is no longer secret or no longer provides economic benefit to the company.

Many companies require their employees to sign a nondisclosure agreement (NDA), confirming that they understand its contents and promise not to share the company’s trade secrets with competitors or any unauthorized individuals. Companies require this both to inform the employees of the importance of keeping certain information secret and to deter them from sharing this information. Having them sign the nondisclosure agreement also gives the company the right to fire the employee or bring charges if the employee discloses a trade secret.

A low-level engineer working at Intel took trade secret information that was valued by Intel of $1 billion when he left his position at the company and went to work at his new employer, Advanced Micro Device (AMD). It was discovered that this person still had access to Intel’s most confidential information even after starting work at the company’s rival competitor. He even used the laptop that Intel provided to him to download 13 critical documents that contained extensive information about the company’s new processor developments and product releases. Unfortunately these stories are not rare and companies are constantly dealing with challenges of protecting the very data that keeps them in business.

Copyright

In the United States, copyright law protects the right of an author to control the public distribution, reproduction, display, and adaptation of his original work. The law covers many categories of work: pictorial, graphic, musical, dramatic, literary, pantomime, motion picture, sculptural, sound recording, and architectural. Copyright law does not cover the specific resource, as does trade secret law. It protects the expression of the idea of the resource instead of the resource itself. A copyright is usually used to protect an author’s writings, an artist’s drawings, a programmer’s source code, or specific rhythms and structures of a musician’s creation. Computer programs and manuals are just two examples of items protected under the Federal Copyright Act. The item is covered under copyright law once the program or manual has been written. Although including a warning and the copyright symbol (©) is not required, doing so is encouraged so others cannot claim innocence after copying another’s work.

The protection does not extend to any method of operations, process, concept, or procedure, but it does protect against unauthorized copying and distribution of a protected work. It protects the form of expression rather than the subject matter. A patent deals more with the subject matter of an invention; copyright deals with how that invention is represented. In that respect, copyright is weaker than patent protection, but the duration of copyright protection is longer. People are provided copyright protection for life plus 50 years.

Computer programs can be protected under the copyright law as literary works. The law protects both the source and object code, which can be an operating system, application, or database. In some instances, the law can protect not only the code, but also the structure, sequence, and organization. The user interface is part of the definition of a software application structure; therefore, one vendor cannot copy the exact composition of another vendor’s user interface.

Copyright infringement cases have exploded in numbers because of the increased number of “warez” sites that use the common BitTorrent protocol. BitTorrent is a peer-to-peer file sharing protocol and is one of the most common protocols for transferring large files. It has been estimated that it accounted for roughly 27 percent to 55 percent of all Internet traffic (depending on geographical location). Warez is a term that pertains to copyrighted works distributed without fees or royalties, and may be traded, in general violation of the copyright law. The term generally refers to unauthorized releases by groups, as opposed to file sharing between friends.

Once a warez site posts copyrighted material, it is very difficult to have it removed because law enforcement is commonly overwhelmed with larger criminal cases and does not have the bandwidth to go after these “small fish.” Another issue with warez sites is that the actual servers may reside in another country; thus, legal jurisdiction makes things more difficult and the country that the server resides within may not even have a copyright law within its legal system. The film and music recording companies have had the most success in going after these types of offenders because they have the funds and vested interest to do so.

Trademark

My trademark is my stupidity.

Response: Good for you!

A trademark is slightly different from a copyright in that it is used to protect a word, name, symbol, sound, shape, color, or combination of these. The reason a company would trademark one of these, or a combination, is that it represents their company (brand identity) to a group of people or to the world. Companies have marketing departments that work very hard in coming up with something new that will cause the company to be noticed and stand out in a crowd of competitors, and trademarking the result of this work with a government registrar is a way of properly protecting it and ensuring others cannot copy and use it.

Companies cannot trademark a number or common word. This is why companies create new names—for example, Intel’s Pentium and Standard Oil’s Exxon. However, unique colors can be trademarked, as well as identifiable packaging, which is referred to as “trade dress.” Thus, Novell Red and UPS Brown are trademarked, as are some candy wrappers.

NOTE In 1883, international harmonization of trademark laws began with the Paris Convention, which in turn prompted the Madrid Agreement of 1891. Today, international trademark law efforts and international registration are overseen by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), an agency of the United Nations.

NOTE In 1883, international harmonization of trademark laws began with the Paris Convention, which in turn prompted the Madrid Agreement of 1891. Today, international trademark law efforts and international registration are overseen by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), an agency of the United Nations.

There have been many interesting trademark legal battles over the years. In one case a person named Paul Specht started a company named “Android Data” and had his company’s trademark approved in 2002. Specht’s company went under and while he attempted to sell it and the trademark, he had no buyers. When Google announced that it was going to release a new phone called the Android, Specht built a new website using his old company’s name to try and prove that he was indeed still using this trademark. Specht took Google to court and asked for $94 million in damages. The court ruled in Google’s favor and found that Google was not liable for trademark damages.

Patent

Patents are given to individuals or companies to grant them legal ownership of, and enable them to exclude others from using or copying, the invention covered by the patent. The invention must be novel, useful, and not obvious—which means, for example, that a company could not patent air. Thank goodness. If a company figured out how to patent air, we would have to pay for each and every breath we took!

After the inventor completes an application for a patent and it is approved, the patent grants a limited property right to exclude others from making, using, or selling the invention for a specific period of time. For example, when a pharmaceutical company develops a specific drug and acquires a patent for it, that company is the only one that can manufacture and sell this drug until the stated year in which the patent is up (usually 20 years from the date of approval). After that, the information is in the public domain, enabling all companies to manufacture and sell this product, which is why the price of a drug drops substantially after its patent expires.

This also takes place with algorithms. If an inventor of an algorithm acquires a patent, she has full control over who can use it in their products. If the inventor lets a vendor incorporate the algorithm, she will most likely get a fee and possibly a license fee on each instance of the product that is sold.

Patents are ways of providing economical incentives to individuals and organizations to continue research and development efforts that will most likely benefit society in some fashion. Patent infringement is huge within the technology world today. Large and small product vendors seem to be suing each other constantly with claims of patent infringement. The problem is that many patents are written at a very high level and maybe written at a functional level. For example, if I developed a technology that accomplishes functionality A, B, and C, you could actually develop your own technology in your own way that also accomplished A, B, and C. You might not even know that my method or patent existed; you just developed this solution on your own. Well, if I did this type of work first and obtained the patent, then I could go after you legally for infringement.

NOTE A patent is the strongest form of intellectual property protection.

NOTE A patent is the strongest form of intellectual property protection.

At the time of this writing, the amount of patent legislation in the technology world is overwhelming. Kodak filed suit against Apple and RIM alleging patent infringement pertaining to resolution previews of videos on on-screen displays. While the U.S. International Trade Commission ruled against Kodak in that case, Kodak had won similar cases against LG and Samsung, which provided them with a licensing deal of $864 million. Soon after the Trade Commission’s ruling, RIM sued Kodak for different patent infringements and Apple also sued Kodak for a similar matter.

Apple has also filed two patent infringement complaints against the mobile phone company HTC, Cupertino did the same with Nokia, and Microsoft sued Motorola over everything from synchronizing e-mail to handset power control functionality. Microsoft sued a company called TomTom over eight car navigation and file management systems patents. A company called i4i, Inc., sued Microsoft for allegedly using its patented XML-authoring technology within its product Word. And Google lost a Linux-related infringement case that cost it $5 million.

This is just a small list of the amount of patent litigation taking place as of the writing of this book. These cases are like watching 100 Ping-Pong matches going on all at the same time, each containing its own characters and dramas, and involving millions and billions of dollars.

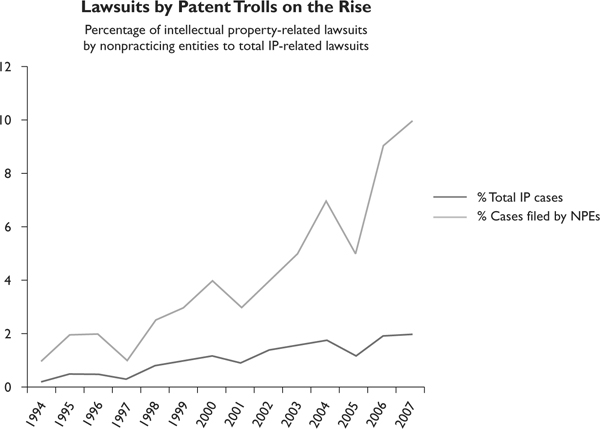

While the various vendors are fighting for market share in their respective industries, another reason for the increase in patent litigation is patent trolls. Patent troll is a term used to describe a person or company who obtains patents not to protect their invention but to aggressively and opportunistically go after another entity who tries to create something based upon their ideas. A patent troll has no intention of manufacturing an item based upon their patent, but wants to get licensing fees from an entity that does manufacture the item. For example, let’s say that I have 10 new ideas for 10 different technologies. I put them through the patent process and get them approved. Now I actually have no desire to put in all the money and risk it takes to actually create these technologies and attempt to bring them to market. I am going to wait until you do this and then I am going to sue you for infringing upon my patent. If I win my court case, you have to pay me licensing fees for the product you developed and brought to market.

Source PatentFreedom © 2008. Data captured as of November 2008.

It is important to do a patent search before putting effort into developing a new methodology, technology, or business method.

Internal Protection of Intellectual Property

Ensuring that specific resources are protected by the previously mentioned laws is very important, but other measures must be taken internally to make sure the resources that are confidential in nature are properly identified and protected.

The resources protected by one of the previously mentioned laws need to be identified and integrated into the company’s data classification scheme. This should be directed by management and carried out by the IT staff. The identified resources should have the necessary level of access control protection, auditing enabled, and a proper storage environment. If it is deemed secret, then not everyone in the company should be able to access it. Once the individuals who are allowed to have access are identified, their level of access and interaction with the resource should be defined in a granular method. Attempts to access and manipulate the resource should be properly audited, and the resource should be stored on a protected system with the necessary security mechanisms.

Employees must be informed of the level of secrecy or confidentiality of the resource, and of their expected behavior pertaining to that resource.

If a company fails in one or all of these steps, it may not be covered by the laws described previously, because it may have failed to practice due care and properly protect the resource that it has claimed to be so important to the survival and competitiveness of the company.

Software Piracy

Software piracy occurs when the intellectual or creative work of an author is used or duplicated without permission or compensation to the author. It is an act of infringement on ownership rights, and if the pirate is caught, he could be sued civilly for damages, be criminally prosecuted, or both.

When a vendor develops an application, it usually licenses the program rather than sells it outright. The license agreement contains provisions relating to the approved use of the software and the corresponding manuals. If an individual or company fails to observe and abide by those requirements, the license may be terminated and, depending on the actions, criminal charges may be leveled. The risk to the vendor that develops and licenses the software is the loss of profits it would have earned.

There are four categories of software licensing. Freeware is software that is publicly available free of charge and can be used, copied, studied, modified, and redistributed without restriction. Shareware, or trialware, is used by vendors to market their software. Users obtain a free, trial version of the software. Once the user tries out the program, the user is asked to purchase a copy of it. Commercial software is, quite simply, software that is sold for or serves commercial purposes. And, finally, academic software is software that is provided for academic purposes at a reduced cost. It can be open source, freeware, or commercial software.

Some software vendors sell bulk licenses, which enable several users to use the product simultaneously. These master agreements define proper use of the software along with restrictions, such as whether corporate software can also be used by employees on their home machines. One other prevalent form of software licensing is the End User Licensing Agreement (EULA). It specifies more granular conditions and restrictions than a master agreement. Other vendors incorporate third-party license-metering software that keeps track of software usability to ensure that the customer stays within the license limit and otherwise complies with the software licensing agreement. The security officer should be aware of all these types of contractual commitments required by software companies. This person needs to be educated on the restrictions the company is under and make sure proper enforcement mechanisms are in place. If a company is found guilty of illegally copying software or using more copies than its license permits, the security officer in charge of this task may be primarily responsible.

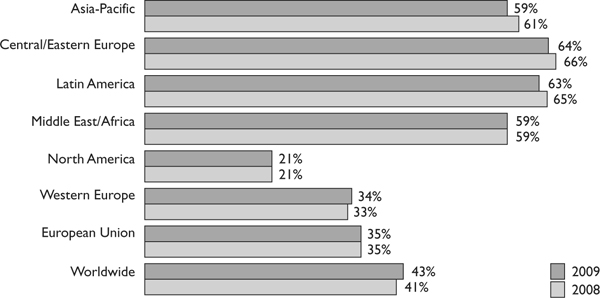

Thanks to easy access to high-speed Internet, employees’ ability—if not the temptation—to download and use pirated software has greatly increased. A study by the Business Software Alliance (BSA) and International Data Corporation (IDC) found that the frequency of illegal software is 36 percent worldwide. This means that for every two dollars’ worth of legal software that is purchased, one dollar’s worth is pirated. Software developers often use these numbers to calculate losses resulting from pirated copies. The assumption is that if the pirated copy had not been available, then everyone who is using a pirated copy would have instead purchased it legally.

Not every country recognizes software piracy as a crime, but several international organizations have made strides in curbing the practice. The Software Protection Association (SPA) has been formed by major companies to enforce proprietary rights of software. The association was created to protect the founding companies’ software developments, but it also helps others ensure that their software is properly licensed. These are huge issues for companies that develop and produce software, because a majority of their revenue comes from licensing fees.

Other international groups have been formed to protect against software piracy, including the Federation Against Software Theft (FAST), headquartered in London, and the Business Software Alliance (BSA), based in Washington, D.C. They provide similar functionality as the SPA and make efforts to protect software around the world. Figure 9-3 shows the results of a BSA 2010 software piracy study that illustrates the breakdown of which world regions are the top offenders. The study also estimates that the total economical damage experienced by the industry was $51.4 billion in losses in 2010.

Software Piracy Rates by Region

Source: Seventh Annual BSA/DC Global Software Piracy Study, May 2010

Figure 9-3 Software piracy rates by region

One of the offenses an individual or company can commit is to decompile vendor object code. This is usually done to figure out how the application works by obtaining the original source code, which is confidential, and perhaps to reverse-engineer it in the hope of understanding the intricate details of its functionality. Another purpose of reverse-engineering products is to detect security flaws within the code that can later be exploited. This is how some buffer overflow vulnerabilities are discovered.

Many times, an individual decompiles the object code into source code and either finds security holes and can take advantage of them or alters the source code to produce some type of functionality that the original vendor did not intend. In one example, an individual decompiled a program that protects and displays e-books and publications. The vendor did not want anyone to be able to copy the e-publications its product displayed and thus inserted an encoder within the object code of its product that enforced this limitation. The individual decompiled the object code and figured out how to create a decoder that would overcome this restriction and enable users to make copies of the e-publications, which infringed upon those authors’ and publishers’ copyrights.

The individual was arrested and prosecuted under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which makes it illegal to create products that circumvent copyright protection mechanisms. Interestingly enough, many computer-oriented individuals protested this person’s arrest, and the company prosecuting (Adobe) quickly decided to drop all charges.

DMCA is a U.S. copyright law that criminalizes the production and dissemination of technology, devices, or services that circumvent access control measures that are put into place to protect copyright material. So if you figure out a way to “unlock” the proprietary way that Barnes & Noble protects its e-books you can be charged under this act. Even if you don’t share the actual copyright-protected books with someone, you still broke this specific law and can be found guilty.

NOTE The European Union passed a similar law called the Copyright Directive.

NOTE The European Union passed a similar law called the Copyright Directive.

Privacy

You don’t even want to know about all the data Google collects on you.

Response: I am sure there are no privacy issues to be concerned about.

Privacy is becoming more threatened as the world relies more and more on technology. There are several approaches to addressing privacy, including the generic approach and regulation by industry. The generic approach is horizontal enactment—rules that stretch across all industry boundaries. It affects all industries, including government. Regulation by industry is vertical enactment. It defines requirements for specific verticals, such as the financial sector and health care. In both cases, the overall objective is twofold. First, the initiatives seek to protect citizens’ personally identifiable information (PII). Second, the initiatives seek to balance the needs of government and businesses to collect and use PII with consideration of security issues.

In response, countries have enacted privacy laws. For example, although the United States already had the Federal Privacy Act of 1974, it has enacted new laws, such as the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), in response to an increased need to protect personal privacy information. These are examples of a vertical approach to addressing privacy, whereas Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and New Zealand’s Privacy Act of 1993 are horizontal approaches.

The U.S. Federal Privacy Act was put into place to protect U.S. citizens’ sensitive information that is collected by government agencies. It states that any data collected must be done in a fair and lawful manner. The data are to be used only for the purposes for which they were collected and held only for a reasonable amount of time. If an agency collects data on a person, that person has the right to receive a report outlining data collected about him if it is requested. Similar laws exist in many countries around the world.

Technology is continually advancing in the amount of data that can be kept in data warehouses, data mining and analysis techniques, and distribution of this mined data. Companies that are data aggregators compile in-depth profiles of personal information on millions of people, even though many individuals have never heard of these specific companies, have never had an account with them, nor have given them permission to obtain personal information. These data aggregators compile, store, and sell personal information.

It seems as though putting all of this information together would make sense. It would be easier to obtain, have one centralized source, be extremely robust—and be the delight of identity thieves everywhere. All they have to do is hack into one location and get enough information to steal thousands of identities.

The Increasing Need for Privacy Laws

Privacy is different from security, and although the concepts can intertwine, they are distinctively different. Privacy is the ability of an individual or group to control who has certain types of information about them. Privacy is an individual’s right to determine what data they would like others to know about themselves, which people are permitted to know that data, and the ability to determine when those people can access it. Security is used to enforce these privacy rights.

The following issues have increased the need for more privacy laws and governance:

• Data aggregation and retrieval technologies advancement

• Large data warehouses are continually being created full of private information.

• Loss of borders (globalization)

• Private data flows from country to country for many different reasons.

• Business globalization.

• Convergent technologies advancements

• Gathering, mining, and distributing sensitive information.

While people around the world have always felt that privacy was important, the fact that almost everything that there is to know about a person (age, sex, financial data, medical data, friends, purchasing habits, criminal behavior, and even Google searches) is in some digital format in probably over 50 different locations makes people even more concerned about their privacy.

Having data quickly available to whomever needs it makes many things in life easier and less time consuming. But this data can just as easily be available to those you do not want to have access to it. Personal information is commonly used in identity theft, financial crimes take place because an attacker knows enough about a person to impersonate him, and people experience extortion because others find out secrets about them.

While some companies and many marketing companies want as much personal information about people as possible, many other organizations do not want to carry the burden and liability of storing and processing so much sensitive data. This opens the organization up to too much litigation risk. But this type of data is commonly required for various business processes. As discussed in Chapter 2, a new position in many organizations has been created to just deal with privacy issues—chief privacy officer. This person is usually a lawyer and has the responsibility of overseeing how the company deals with sensitive data in a responsible and legal manner. Many companies have had to face legal charges and civil suits for not properly protecting privacy data, so they have hired individuals who are experts in this field.

Privacy laws are popping up like weeds in a lawn. Many countries are creating new legislation, and as of this writing over 30 U.S. states have their own privacy information disclosure laws. While this illustrates the importance that society puts on protecting individuals’ privacy, the amount of laws and their variance make it very difficult for a company to ensure that it is in compliance with all of them.

As a security professional, you should understand the types of privacy data your organization deals with and help to ensure that it is meeting all of its legal and regulatory requirements pertaining to this type of data.

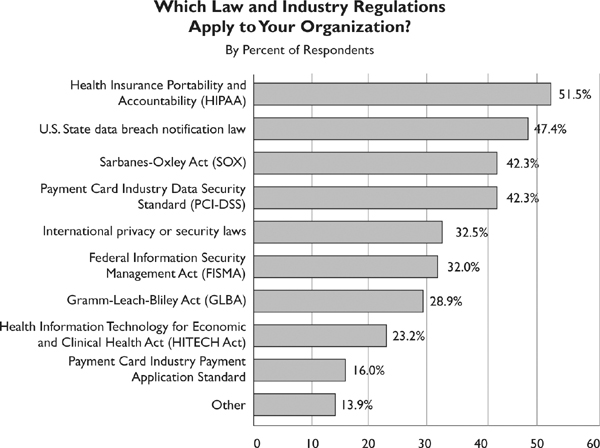

Laws, Directives, and Regulations

Regulation in computer and information security covers many areas for many different reasons. Some issues that require regulation are data privacy, computer misuse, software copyright, data protection, and controls on cryptography. These regulations can be implemented in various arenas, such as government and private sectors for reasons dealing with environmental protection, intellectual property, national security, personal privacy, public order, health and safety, and prevention of fraudulent activities.

Security professionals have so much to keep up with these days, from understanding how the latest worm attacks work and how to properly protect against them, to how new versions of DoS attacks take place and what tools are used to accomplish them. Professionals also need to follow which new security products are released and how they compare to the existing products. This is followed up by keeping track of new technologies, service patches, hotfixes, encryption methods, access control mechanisms, telecommunications security issues, social engineering, and physical security. Laws and regulations have been ascending the list of things that security professionals also need to be aware of. This is because organizations must be compliant with more and more laws and regulations, and noncompliance can result in a fine or a company going out of business, with certain executive management individuals ending up in jail.