Chapter 1

Security and Risk Management

This chapter covers the following topics:

Security Terms: Concepts discussed include confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA); auditing and accounting; non-repudiation; default security posture; defense in depth; abstraction; data hiding; and encryption.

Security Governance Principles: Concepts discussed include security function alignment, organizational processes, organizational roles and responsibilities, security control frameworks, and due care and due diligence.

Compliance: Concepts discussed include contractual, legal, industry standards, and regulatory compliance and privacy requirements compliance.

Legal and Regulatory Issues: Concepts discussed include computer crime concepts, major legal systems, licensing and intellectual property, cyber crimes and data breaches, import/export controls, trans-border data flow, and privacy.

Professional Ethics: Ethics discussed include (ISC)2 Code of Ethics, Computer Ethics Institute, Internet Architecture Board, and organizational code of ethics.

Security Documentation: Documentation types include policies, processes, procedures, standards, guidelines, and baselines.

Business Continuity: Concepts discussed include business continuity and disaster recovery concepts, scope and plan, and BIA development.

Personnel Security Policies and Procedures: Policies and procedures discussed include candidate screening and hiring; employment agreements and policies; onboarding and offboarding processes; vendor, consultant, and contractor agreements and controls; compliance policy requirements; privacy policy requirements, job rotation, and separation of duties.

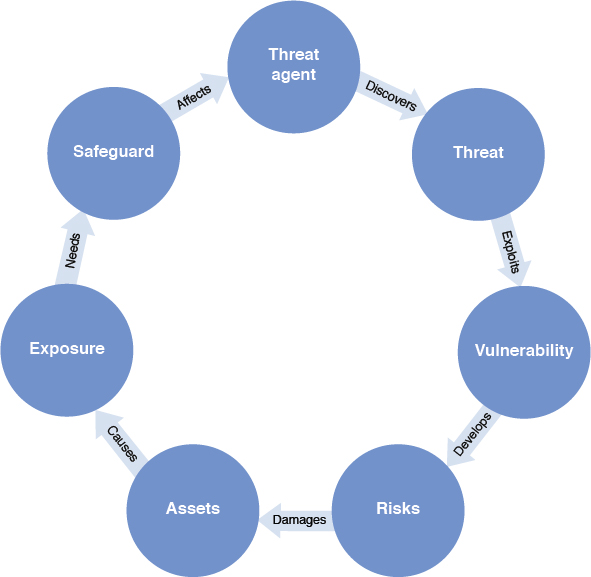

Risk Management Concepts: Concepts discussed include asset; asset valuation; vulnerability; threat; threat agent; exploit; risk; exposure; countermeasure; risk appetite; attack; breach; risk management policy; risk management team; risk analysis team; risk assessment; implementation; control categories; control types; control assessment, monitoring, and measurement; reporting and continuous improvement; and risk frameworks.

Geographical Threats: Concepts discussed include internal versus external threats, natural threats, system threats, human threats, and politically motivated threats.

Threat Modeling: Concepts discussed include threat modeling concepts, threat modeling methodologies, identifying threats, potential attacks, and remediation technologies and processes.

Security Risks in the Supply Chain: Concepts discussed include risks associated with hardware, software, and services; third-party assessment and monitoring; minimum security requirements; and service-level requirements.

Security Awareness, Education, and Training: Concepts discussed include levels required, methods and techniques, and periodic content reviews.

The Security and Risk Management domain addresses a broad array of topics including the fundamental information security principles of confidentiality, integrity and availability, governance, legal systems, privacy, the regulatory environment, personnel security, risk management, threat modeling, business continuity, supply chain risk, and professional ethics. Out of 100% of the exam, this domain carries an average weight of 15%, which is the highest weight of all the eight domains. So, pay close attention to the many details in this chapter!

Information security governance involves the principles, frameworks, and methods that establish criteria for protecting information assets, including security awareness. Risk management allows organizations to identify, measure, and control organizational risks. Threat modeling allows organizations to identify threats and potential attacks and implement appropriate mitigations against these threats and attacks. These facets ensure that security controls that are implemented are in balance with the operations of the organization. Each organization must develop a well-rounded, customized security program that addresses the needs of the organization while ensuring that the organization exercises due care and due diligence in its security plan. Acquisitions present special risks that management must understand prior to completing acquisitions.

Security professionals must take a lead role in their organization’s security program and act as risk advisors to management. In addition, security professionals must ensure that they understand current security issues and risks, governmental and industry regulations, and security controls that can be implemented. Professional ethics for security personnel must also be understood. Security is an ever-evolving, continuous process, and security professionals must be watchful.

Business continuity and disaster recovery ensures that the organization can recover from any attack or disaster that affects operations. Using the results from the risks assessment, security professionals should ensure that the appropriate business continuity and disaster recovery plans are created, tested, and revised at appropriate intervals.

In this chapter, you will learn how to use the information security governance and risk management components to assess risks, implement controls for identified risks, monitor control effectiveness, and perform future risk assessments.

Foundation Topics

Security Terms

When implementing security and managing risk, there are several important security principles and terms that you must keep in mind: confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA); auditing and accounting; non-repudiation; default security posture; defense in depth; abstraction; data hiding; and encryption.

CIA

The three fundamentals of security are confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA), often referred to as the CIA triad. Although the CIA triad is being introduced here, each principle of the triad should be considered in every aspect of security design. The CIA triad could easily be discussed in any domain of the CISSP exam.

Most security issues result in a violation of at least one facet of the CIA triad. Understanding these three security principles will help security professionals ensure that the security controls and mechanisms implemented protect at least one of these principles.

Every security control that is put into place by an organization fulfills at least one of the security principles of the CIA triad. Understanding how to circumvent these security principles is just as important as understanding how to provide them.

A balanced security approach should be implemented to ensure that all three facets are considered when security controls are implemented. When implementing any control, you should identify the facet that the control addresses. For example, RAID addresses data availability, file hashes address data integrity, and encryption addresses data confidentiality. A balanced approach ensures that no facet of the CIA triad is ignored.

Confidentiality

To ensure confidentiality, you must prevent the disclosure of data or information to unauthorized entities. As part of confidentiality, the sensitivity level of data must be determined before putting any access controls in place. Data with a higher sensitivity level will have more access controls in place than data at a lower sensitivity level. Identification, authentication, and authorization can be used to maintain data confidentiality.

The opposite of confidentiality is disclosure. Encryption is probably the most popular example of a control that provides confidentiality.

Integrity

Integrity, the second part of the CIA triad, ensures that data and systems are protected from unauthorized modification or data corruption. The goal of integrity is to preserve consistency, specifically:

Data integrity: Implies information is known to be good, and that the information can be trusted as being complete, consistent, and accurate.

System integrity: Implies that a system will work as intended.

The opposite of integrity is corruption. Hashing can be used to prove (or disprove) data integrity.

Availability

Availability means ensuring that information, systems, and supporting infrastructure are operating and accessible when needed. The two main instances in which availability is affected are (1) when attacks are carried out that disable or cripple a system and (2) when service loss occurs during and after disasters. Each system should be assessed in terms of its criticality to organizational operations. Controls should be implemented based on each system’s criticality level.

Availability is the opposite of destruction or isolation. Fault-tolerant technologies, such as RAID or redundant sites, are examples of controls that help improve availability.

Auditing and Accounting

Auditing and accounting are two related terms in organizational security. Auditing is the internal process of providing a manual or systematic measurable technical assessment of a system or application, while accounting is the logging of access and use of information resources. Accountability is the process of tracing actions to the source. Security professionals can perform audits of user or service accounts, account usage, application usage, device usage, and even permission usage. The purpose of internal auditing is to provide accountability. Regular audits should be carried out to ensure that the security policies in place are enforced and being followed. Accounting then is used to determine what changes need to be made.

Organizations should have a designated party who is responsible for ensuring that auditing and accounting of enterprise security are being completed regularly. While computer security audits can be performed by internal personnel, such as corporate internal auditors, the audits may also need to be completed by federal or state regulators, external auditors, or consultants.

Keep in mind that in many contexts auditing can also be a third-party activity whereby an organization gains independent assurance based on evidence. With this type of auditing, the third party is usually assessing an organization’s compliance with standards or other organizations’ guidelines.

Non-Repudiation

Non-repudiation is the assurance that a sender cannot deny an action. This is usually seen in electronic communications where one party denies sending a contract, document, or email. Non-repudiation means putting measures in place that will prevent one party from denying it sent a message.

A valid digital signature gives a recipient reason to believe that the message was created by a known sender (authentication), that the sender cannot deny having sent the message (non-repudiation), and that the message was not altered in transit (integrity).

Default Security Posture

An organization’s approach to information security directly affects its access control strategy. For a default security posture, organizations must choose between the allow-by-default or deny-by-default options. As implied by its name, an allow-by-default posture permits access to any data unless a need exists to restrict access. The deny-by-default posture is much stricter because it denies any access that is not explicitly permitted. Government and military institutions and many commercial organizations use a deny-by-default posture.

Today few organizations implement either of these postures to its fullest. In most organizations, you see some mixture of the two. Although the core posture should guide the organization, organizations often find that this mixture is necessary to ensure that data is still protected while providing access to a variety of users. For example, a public website might grant all HTTP and HTTPS content, but deny all other content.

Defense in Depth

A defense-in-depth strategy refers to the practice of using multiple layers of security between data and the resources on which it resides and possible attackers. The first layer of a good defense-in-depth strategy is appropriate access control strategies. Access controls exist in all areas of an information systems (IS) infrastructure (more commonly referred to as an IT infrastructure), but a defense-in-depth strategy goes beyond access control. It also considers software development security, asset security, and all other domains of the CISSP realm.

Figure 1-1 shows an example of the defense-in-depth concept.

Abstraction

Abstraction is the process of taking away or removing characteristics from something to reduce it to a set of essential characteristics. Abstraction usually results in named entities with a set of characteristics that help in their identification. However, unnecessary characteristics are hidden. Abstraction is related to both encapsulation and data hiding.

Data Hiding

Data hiding is the principle whereby data about a known entity is not accessible to certain processes or users. For example, a database may collect information about its users, including their name, job title, email address, and phone number, that you want all users to be able to access. However, you may not want the public to be able to access their Social Security numbers, birthdate, or other protected personally identifiable information (PII). Encapsulation is a popular technique that provides data hiding.

Encryption

Encryption is the process of converting information or data into a code, especially to prevent unauthorized access. Data can be encrypted while at rest, in transit, and in use. Encryption is covered in more detail in Chapter 3, “Security Architecture and Engineering.”

Security Governance Principles

Corporate governance is the system by which organizations are directed and controlled. Governance structures and principles identify the distribution of rights and responsibilities. As applied to information cybersecurity, governance is the responsibility of leadership to

Determine and articulate the organization’s desired state of security

Provide the strategic direction, resources, funding, and support to ensure that the desired state of security can be achieved and sustained

Maintain responsibility and accountability through oversight

Organizations should use security governance principles to ensure that all organizational assets are protected. Organizations often use best practices that are established by organizations, such as National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) or Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL). Because information technology is an operational necessity, management must take an active role in any security governance initiative.

Security governance assigns rights and uses an accountability framework to ensure appropriate decision making. It must ensure that the framework used is aligned with the business strategy. Security governance gives directions, establishes standards and principles, and prioritizes investments. It is the responsibility of the organization’s board of directors and executive management.

The IT Governance Institute (ITGI) issued the Board Briefing on IT Governance, 2nd Edition, which is available from the Information Systems Audit and Control Association’s (ISACA’s) website at www.isaca.org/Knowledge-Center/Research/ResearchDeliverables/Pages/Board-Briefing-on-IT-Governance-2nd-Edition.aspx. It provides the following definition for IT governance:

IT governance is the responsibility of the board of directors and executive management. It is an integral part of enterprise governance and consists of the leadership and organizational structures and processes that ensure that the organization’s IT sustains and extends the organization’s strategies and objectives.

According to this publication, IT governance covers strategic alignment, value delivery, risk management, resource management, and performance measurement. It includes checklists and tools to help an organization’s board of directors and executive management ensure IT governance.

Security governance principles include security function alignment, organizational processes, organizational roles and responsibilities, security control frameworks, and due care and due diligence.

Security Function Alignment

The security function must align with the business strategy, goals, mission, and objectives of the organization. Every information security decision must be informed by organizational goals and be in alignment with strategic objectives. When strategically aligned, security functions as a business enabler that adds value.

It is critical that organizations implement a threat modeling program (which we will discuss later in this chapter), continually reassess the threat environment, including new adversaries, and proactively adapt their information security program.

Organizational Strategies and Goals

The organizational security strategy and goals must be documented. Security management protects organizational assets using physical, administrative, and logical controls. While management is responsible for the development of the organization’s security strategy, security professionals within the organization are responsible for carrying it out. Therefore, security professionals should be involved in the development of the organizational security strategy and goals.

A strategy is a plan of action or a policy designed to achieve a major or overall aim. Goals are the desired results from the security plan. A security management team must address all areas of security, including protecting personnel, physical assets, and data, when designing the organization’s security strategy and goals. The strategy and goals should change over time as the organization grows and changes and the world changes, too. Years ago, organizations did not need to worry about their data being stolen over the Internet. But today, the Internet is one of the most popular mediums used to illegally obtain confidential organizational data.

Organizational Mission and Objectives

The organization’s mission and objectives should already be adopted and established by organizational management or the board of directors. An organization’s security management team must ensure that any security strategy and goals fit with the mission and objectives of the organization. Information and the assets that support the organization’s mission must be protected as part of the security strategy and goals.

The appropriate policies, procedures, standards, and guidelines must be implemented to ensure that organizational risk is kept within acceptable levels. Security professionals will advise management on organizational risks. Organizational risk is also affected by government regulations, which may force an organization to implement certain measures that they had not planned. Weighing the risks to the organization and choosing whether to implement security controls are ultimately the job of senior management.

Security management ensures that risks are identified and adequate controls are implemented to mitigate the risks, all within the context of supporting the organizational mission and objectives.

Business Case

A business case is a formal document that gives the reasons behind an organizational project or initiative and usually includes financial justification for a project or an initiative. The security management team should develop a formal business case for the overall security assessment of an organization. Once the organization’s security assessment is complete and its business case has been created, management will decide how to proceed.

At that point, other business cases for individual security projects will need to be developed. For example, if management wants the security management team to ensure that the organization’s internal network is protected from attacks, the security management team may draft a business case that explains the devices that need to be implemented to meet this goal. This business case may include firewalls, intrusion detection systems (IDSs), access control lists (ACLs), and other devices, and it should detail how the devices will provide protection.

Security Budget, Metrics, and Effectiveness

The chief security officer (CSO) or other designated high-level manager prepares the organization’s security budget, determines the security metrics, and reports on the effectiveness of the security program. This officer must work with other subject matter experts (SMEs) to ensure that all security costs are accounted for, including development, testing, implementation, maintenance, personnel, and equipment. The budgeting process requires an examination of all risks and ensures that security projects with this best cost/benefit ratio are implemented. Projects that take longer than 12–18 months are long-term and strategic and require more resources and funding to complete.

Security metrics provide information on both short- and long-term trends. By collecting these metrics and comparing them on a day-to-day basis, a security professional can determine the daily workload. When the metrics are compared over a longer period of time, the trends that occur can help to shape future security projects and budgets. Procedures should state who will collect the metrics, which metrics will be collected, when the metrics will be collected, and what the thresholds are that will trigger corrective actions. Security professionals should consult with the information security governance frameworks listed later in this chapter, particularly ISO/IEC 27004:2016 and NIST 800-55 Rev. 1, for help in establishing metrics guidelines and procedures.

Although the security team should analyze metrics on a daily basis, periodic analysis of the metrics by a third party can ensure the integrity and effectiveness of the security metrics by verifying the results of the internal team. Data from the third party should be used to improve the security program and security metrics process.

Resources

If the appropriate resources are not allocated to an organization’s security function, even the best-laid security plans will fail. These resources include, but are not limited to, security personnel, devices, and controls. As discussed in the “Security Budget, Metrics, and Effectiveness” section, resource allocation is limited based on the security budget. Risk analysis helps an organization determine which security resources are most important and which are not necessary. But keep in mind that as the security function of the organization is constantly changing, so should the resource allocation to the security function change as needed. What may have been cost-prohibitive last year may become a necessity this year, and what may have been a necessity a few years ago may now be considered outdated and may not provide the level of protection you need. For this reason, security professionals should continuously revisit the risk analysis process to determine what improvements can be made in the security function of an organization.

Security professionals should also understand what personnel resources are needed to support any security function. This may include, but is not limited to, data owners, system administrators, network administrators, IT technicians, software developers, law enforcement, and accounting officers. The size of the organization will influence the availability of resources to any organizational security function. Security professionals should work to build relationships with all personnel resources to ensure a successful security program.

Organizational Processes

To understand organizational processes, organizations must determine the work needed to accomplish a goal, assign those tasks to individuals, and arrange those individuals in a decision-making organizational structure. The end result of documenting the processes is an organization that consists of unified parts acting in harmony to execute tasks to achieve goals. But all organizations go through periods of growth and decline. Often during these periods, organizations will go through acquisitions, mergers, and divestitures. In addition, governance committees will be formed to help improve the organization and its processes.

Acquisitions and Divestitures

An acquisition occurs when one organization purchases another, and a merger occurs when two organizations decide to join together to become one organization. In both cases, they can be considered friendly or hostile.

Security professionals should bring several considerations to the attention of management to ensure that organizational security does not suffer as a result of an acquisition or a merger. The other organization may have new data and technology types that may need more protection than is currently provided. For example, the acquired organization may allow personnel to bring their own devices and use them on the network. While a knee-jerk reaction may be to just implement the same policy as in the current organization, security professionals should assess why the personal devices are allowed and how ingrained this capability is in the organization’s culture.

Another acquisition or merger consideration for security professionals is that the staff at the other organization may not have the appropriate security awareness training. If training has not been given, it may be imperative that security awareness training be deployed as soon as possible to the staff of the acquired company.

When acquisitions or mergers occur, usually a percentage of personnel are not retained. Security professionals should understand any threats from former personnel and any new threats that may arise due to the acquisition or merger. Security professionals must understand these threats so they can develop plans to mitigate the threats.

As part of a merger or acquisition, technology is usually integrated. This integration can present vulnerabilities that the organization would not have otherwise faced. For example, if an acquired company maintains a legacy system because personnel need it, the acquiring organization may need to take measures to protect the legacy system or to deploy a new system that will replace it.

Finally, with an acquisition or a merger, new laws, regulations, and standards may need to be implemented across the entire new organization. Relationships with business partners, vendors, and other entities also need to be reviewed. Security professionals must ensure that they properly advise management about any security issues that may arise.

A divestiture, which is the opposite of an acquisition, occurs when part of an organization is sold off or separated from the original organization. A divestiture impacts personnel because usually a portion of the personnel goes with the divestiture.

As with acquisitions, with divestitures, security professionals should bring certain considerations to the attention of management to ensure that organizational security does not suffer. Data leakage may occur as a result of exiting personnel. Personnel who have been laid off as a result of the divestiture are of particular worry. Tied to this is the fact that the exiting personnel have access rights to organizational assets. These access rights must be removed at the appropriate time, and protocols and ports that are no longer needed should be removed or closed.

Security professionals should also consider where the different security assets and controls will end up. If security assets are part of the divestiture, steps should be taken to ensure that replacements are implemented prior to the divestiture, if needed. In addition, policies and procedures should be reviewed to ensure that they reflect the new organization’s needs.

Whether an organization is going through an acquisition, a merger, or a divestiture, it is vital that security professionals be proactive to protect the organization.

Governance Committees

A governance committee recruits and recommends members of an organization’s governing board (e.g., board of directors or trustees). The governance committee should be encouraged to include among the board members individuals who understand information security and risks.

A board committee (generally the audit or enterprise risk management committee) is generally tasked with the oversight of information security. Management-level security professionals should make themselves available for briefings as well as establish a direct line of communication with the designated committee.

Organizational Roles and Responsibilities

Although all organizations have layers of responsibility within the organization, cybersecurity is generally considered the responsibility of everyone in the organization. This section covers the responsibilities of the different roles within an organization.

Board of Directors

An organization’s board of directors includes individuals who are nominated by a governance committee and elected by shareholders to ensure that the organization is run properly. The loyalty of the board of directors should be to the shareholders, not high-level management. Members of the board of directors should maintain their independence from all organizational personnel, especially if the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act or Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) applies to the organization.

Note

All laws that are pertinent to the CISSP exam are discussed later in this chapter. Keep in mind that for testing purposes, security professionals only need to understand the types of organizations and data that these laws affect.

Senior officials, including the board of directors and senior management, must perform their duties with the care that ordinary, prudent people would exercise in similar circumstances. This is known as the prudent-man rule. Due care and due diligence, discussed later in this chapter, also affect members of the board of directors and high-level management.

Management

High-level management has the ultimate responsibility for preserving and protecting organizational data. High-level management includes the CEO, CFO, CIO, CPO, and CSO. Other management levels, including business unit managers and business operations managers, have security responsibilities as well.

The chief executive officer (CEO) is the highest managing officer in any organization and reports directly to the shareholders. The CEO must ensure that an organization grows and prospers.

The chief financial officer (CFO) is the officer responsible for all financial aspects of an organization. Although structurally the CFO might report directly to the CEO, the CFO must also provide financial data for the shareholders and government entities.

The chief information officer (CIO) is the officer responsible for all information systems and technology used in the organization and reports directly to the CEO or CFO. The CIO usually drives the effort to protect company assets, including any organizational security program.

The chief privacy officer (CPO) is the officer responsible for private information and usually reports directly to the CIO. As a newer position, this role is still considered optional but is becoming increasingly popular, especially in organizations that handle lots of private information, including medical institutions, insurance companies, and financial institutions.

The chief security officer (CSO) is the officer who leads any security effort and reports directly to the CEO. Although this role is considered optional, this role must solely be focused on security matters. Its independence from all other roles must be maintained to ensure that the organization’s security is always the focus of the CSO. This role implements and manages all aspects of security, including risk analysis, security policies and procedures, incident handling, security awareness training, and emerging technologies.

Security professionals should ensure that all risks are communicated to executive management and the board of directors, if necessary. Executive management should maintain a balance between acceptable risk and business operations. While executive management is not concerned with the details of any security implementations, the costs or benefits of any security implementation and any residual risk after such implementation will be vital in ensuring their buy-in to the implementation.

Business unit managers provide departmental information to ensure that appropriate controls are in place for departmental data. Often business unit managers are classified as the data owner for all departmental data. Some business unit managers have security duties. For example, the business operations department manager would be best suited to oversee the security policy development.

Audit Committee

An audit committee evaluates an organization’s financial reporting mechanism to ensure that financial data is accurate. This committee performs an internal audit and engages independent auditors as needed. Members of this committee must obtain appropriate education on a regular basis to ensure that they can oversee financial reporting and enforce accountability in the financial processes.

Data Owner

The main responsibility of the data or information owner is to determine the classification level of the information he owns and to protect the data for which he is responsible. This role approves or denies access rights to the data. However, the data owner usually does not handle the implementation of the data access controls.

The data owner role is usually filled by an individual who understands the data best through membership in a particular business unit. Each business unit should have a data owner. For example, a human resources department employee better understands the human resources data than an accounting department employee.

Data Custodian

The data custodian implements the information classification and controls after they are determined by the data owner. Although the data owner is usually an individual who understands the data, the data custodian does not need any knowledge of the data beyond its classification levels. Although a human resources manager should be the data owner for the human resources data, an IT department member could act as the data custodian for the data.

System Owner

A system owner owns one or more systems and must ensure that the appropriate controls are in place on those systems. Although a system has a single system owner, multiple data owners can be responsible for the information on the system. Therefore, system owners must be able to manage the needs of multiple data owners and implement the appropriate procedures to ensure that the data is secured.

System Administrator

A system administrator performs the day-to-day administration of one or more systems. These day-to-day duties include adding and removing system users and installing system software.

Security Administrator

A security administrator maintains security devices and software, including firewalls, antivirus software, and so on. The main focus of the security administrator is security, whereas the main focus of a system administrator is the system availability and the main focus of the network administrator is network availability. The security administrator reviews all security audit data.

Security Analyst

A security analyst analyzes the security needs of the organization and develops the internal information security governance documents, including policies, standards, and guidelines. The role focuses on the design of security, not its implementation.

Application Owner

An application owner determines the personnel who can access an application. Because most applications are owned by a single department, business department managers usually fill this role. However, the application owner does not necessarily perform the day-to-day administration of the application. This responsibility can be delegated to a member of the IT staff because of the technical skills needed.

Supervisor

A supervisor manages a group of users and any assets owned by this group. Supervisors must immediately communicate any personnel role changes that affect security to the security administrator.

User

A user is any person who accesses data to perform their job duties. Users should understand any security procedures and policies for the data to which they have access. Supervisors are responsible for ensuring that users have the appropriate access rights.

Auditor

An auditor monitors user activities to ensure that the appropriate controls are in place. Auditors need access to all audit and event logs to verify compliance with security policies. Both internal and external auditors can be used.

Security Control Frameworks

Many organizations have developed security management frameworks and methodologies to help guide security professionals. These frameworks and methodologies include security program development standards, enterprise and security architect development frameworks, security controls development methods, corporate governance methods, and process management methods. Frameworks, standards, and methodologies are often discussed together because they are related. Standards are accepted as best practices, whereas frameworks are practices that are generally employed. Standards are specific, while frameworks are general. Methodologies are a system of practices, techniques, procedures, and rules used by those who work in a discipline. In this section we will cover all three as they relate to security controls.

This section discusses the following frameworks and methodologies and explains where they are used:

ISO/IEC 27000 Series

Zachman Framework

TOGAF

DoDAF

MODAF

SABSA

COBIT

NIST 800 Series

HITRUST CSF

CIS Critical Security Controls

COSO

OCTAVE

ITIL

Six Sigma

CMMI

CRAMM

Top-down versus bottom-up approach

Security program life cycle

Note

Organizations should select the framework, standard, and/or methodology that represents the organization in the most useful manner, based on the needs of the stakeholders.

ISO/IEC 27000 Series

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO), often incorrectly referred to as the International Standards Organization, joined with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) to standardize the British Standard 7799 (BS7799) to a new global standard that is now referred to as ISO/IEC 27000 Series. While technically not a framework, ISO 27000 is a security program development standard on how to develop and maintain an information security management system (ISMS).

The 27000 Series includes a list of standards, each of which addresses a particular aspect of ISMSs. These standards are either published or in development. The following standards are included as part of the ISO/IEC 27000 Series at the time of this writing:

27000:2018—Published overview of ISMSs and vocabulary

27001:2013—Published ISMS requirements

27002:2013—Published code of practice for information security controls

27003:2017—Published guidance on the requirements for an ISMS

27004:2016—Published ISMS monitoring, measurement, analysis, and evaluation guidelines

27005:2011—Published information security risk management guidelines

27006:2015—Published requirements for bodies providing audit and certification of ISMS

27007:2017—Published ISMS auditing guidelines

27008:2011—Published guidelines for auditors on information security controls

27009:2016—Published sector-specific application of ISO/IEC 27001 guidelines

27010:2015—Published information security management for inter-sector and inter-organizational communications guidelines

27011:2016—Published telecommunications organizations information security management guidelines

27013:2015—Published integrated implementation of ISO/IEC 27001 and ISO/IEC 20000-1 guidance

27014:2013—Published information security governance guidelines

27016:2014—Published ISMS organizational economics guidelines

27017:2015—Published code of practice for information security controls based on ISO/IEC 27002 for cloud services

27018:2014—Published code of practice for protection of personally identifiable information (PII) in public clouds acting as PII processors

27019:2017—Published information security controls for the energy utility industry guidelines

27021:2017—Published competence requirements for information security management systems professionals

27023:2015—Published mapping the revised editions of ISO/IEC 27001 and ISO/IEC 27002

27031:2011—Published information and communication technology readiness for business continuity guidelines

27032:2012—Published cybersecurity guidelines

27033-1:2015—Published network security overview and concepts

27033-2:2012—Published network security design and implementation guidelines

27033-3:2010—Published network security threats, design techniques, and control issues guidelines

27033-4:2014—Published securing communications between networks using security gateways

27033-5:2013—Published securing communications across networks using virtual private networks (VPNs)

27033-6:2016—Published securing wireless IP network access

27034-1:2011—Published application security overview and concepts

27034-2:2015—Published application security organization normative framework guidelines

27034-5:2017—Published application security protocols and controls data structure guidelines

27034-6:2016—Published case studies for application security

27035-1:2016—Published information security incident management principles

27035-2:2016—Published information security incident response readiness guidelines

27036-1:2014—Published information security for supplier relationships overview and concepts

27036-2:2014—Published information security for supplier relationships common requirements guidelines

27036-3:2013—Published information and communication technology (ICT) supply chain security guidelines

27036-4:2016—Published guidelines for security of cloud services

27037:2012—Published digital evidence identification, collection, acquisition, and preservation guidelines

27038:2014—Published information security digital redaction specification

27039:2015—Published IDS selection, deployment, and operations guidelines

27040:2015—Published storage security guidelines

27041:2015—Published guidance on assuring suitability and adequacy of incident investigative method

27042:2015—Published digital evidence analysis and interpretation guidelines

27043:2015—Published incident investigation principles and processes

27050-1:2016—Published electronic discovery (eDiscovery) overview and concepts

27050-3:2017—Published code of practice for electronic discovery

27799:2016—Published information security in health organizations guidelines

These standards are developed by the ISO/IEC bodies, but certification or conformity assessment is provided by third parties.

Note

The numbers after the colon for each standard stand for the year that the standard was published. You can find more information regarding ISO standards at https://www.iso.org. All ISO standards are copyrighted and must be purchased to obtain detailed information in the standards.

Zachman Framework

The Zachman Framework, an enterprise architecture framework, is a two-dimensional classification system based on six communication questions (What, Where, When, Why, Who, and How) that intersect with different perspectives (Executive, Business Management, Architect, Engineer, Technician, and Enterprise). This system allows analysis of an organization to be presented to different groups in the organization in ways that relate to the groups’ responsibilities. Although this framework is not security oriented, using this framework helps you to relay information for personnel in a language and format that is most useful to them.

The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF)

TOGAF, another enterprise architecture framework, helps organizations design, plan, implement, and govern an enterprise information architecture. TOGAF is based on four interrelated domains: technology, applications, data, and business.

Department of Defense Architecture Framework (DoDAF)

DoDAF is an architecture framework that organizes a set of products under eight views: all viewpoint (required) (AV), capability viewpoint (CV), data and information viewpoint (DIV), operation viewpoint (OV), project viewpoint (PV), services viewpoint (SvcV), standards viewpoint (STDV), and systems viewpoint (SV). It is used to ensure that new DoD technologies integrate properly with the current infrastructures.

British Ministry of Defence Architecture Framework (MODAF)

MODAF is an architecture framework that divides information into seven viewpoints: strategic viewpoint (StV), operational viewpoint (OV), service-oriented viewpoint (SOV), systems viewpoint (SV), acquisition viewpoint (AcV), technical viewpoint (TV), and all viewpoint (AV).

Sherwood Applied Business Security Architecture (SABSA)

SABSA is an enterprise security architecture framework that is similar to the Zachman Framework. It uses the six communication questions (What, Where, When, Why, Who, and How) that intersect with six layers (operational, component, physical, logical, conceptual, and contextual). It is a risk-driven architecture. See Table 1-1.

Table 1-1 SABSA Framework Matrix

Viewpoint |

Layer |

Assets (What) |

Motivation (Why) |

Process (How) |

People (Who) |

Location (Where) |

Time (When) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Business |

Contextual |

Business |

Risk model |

Process model |

Organizations and relationships |

Geography |

Time dependencies |

Architect |

Conceptual |

Business attributes profile |

Control objectives |

Security strategies and architectural layering |

Security entity model and trust framework |

Security domain model |

Security-related lifetimes and deadlines |

Designer |

Logical |

Business information model |

Security policies |

Security services |

Entity schema and privilege profiles |

Security domain definitions and associations |

Security processing cycle |

Builder |

Physical |

Business data model |

Security rules, practices, and procedures |

Security mechanism |

Users, applications, and interfaces |

Platform and network infrastructure |

Control structure execution |

Tradesman |

Component |

Detailed data structures |

Security standards |

Security tools and products |

Identities, functions, actions, and ACLs |

Processes, nodes, addresses, and protocols |

Security step timing and sequencing |

Facilities Manager |

Operational |

Operational continuity assurance |

Operation risk management |

Security service management and support |

Application and user management and support |

Site, network, and platform security |

Security operations schedule |

Control Objectives for Information and Related Technology (COBIT)

COBIT 5 is a security controls development framework that documents five principles:

Meeting stakeholder needs

Covering the enterprise end-to-end

Applying a single integrated framework

Enabling a holistic approach

Separating governance from management

These five principles drive control objectives categorized into seven enablers:

Principles, policies, and frameworks

Processes

Organizational structures

Culture, ethics, and behavior

Information

Services, infrastructure, and applications

People, skills, and competencies

It also covers the 37 governance and management processes that are needed for enterprise IT.

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication (SP) 800 Series

The NIST 800 Series is a set of documents that describe U.S. federal government computer security policies, procedures, and guidelines. While NIST publications are written to provide guidance to U.S. government agencies, other organizations can and often do use them. Each SP within the series defines a specific area. Some of the publications included as part of the NIST 800 Series at the time of this writing are as follows:

SP 800-12 Rev. 1: Introduces information security principles.

SP 800-16 Rev. 1: Describes information technology/cybersecurity role-based training for federal departments, agencies, and organizations.

SP 800-18 Rev. 1: Provides guidelines for developing security plans for federal information systems.

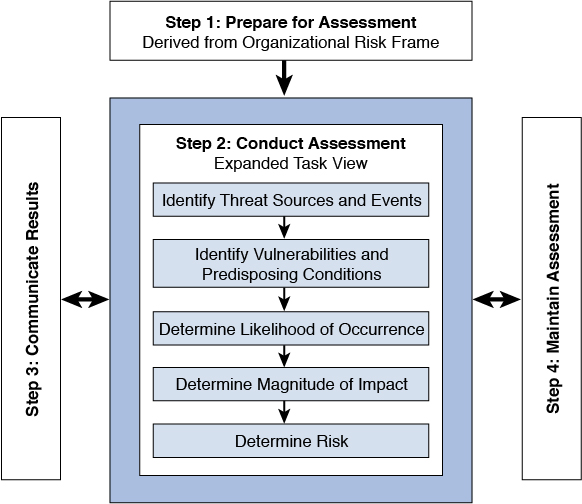

SP 800-30 Rev. 1: Provides guidance for conducting risk assessments of federal information systems and organizations, amplifying the guidance in SP 800-39.

SP 800-34 Rev. 1: Provides guidelines on the purpose, process, and format of information system contingency planning development.

SP 800-35: Provides assistance with selecting, implementing, and managing IT security services through the IT security services life cycle.

SP 800-36: Provides guidelines for choosing IT security products.

SP 800-37 Rev. 1: Provides guidelines for applying the risk management framework to federal information systems (Rev. 2 pending).

SP 800-39: Provides guidance for an integrated, organization-wide program for managing information security risk.

SP 800-50: Identifies the four critical steps in the IT security awareness and training life cycle: (1) awareness and training program design; (2) awareness and training material development; (3) program implementation; and (4) post-implementation. It is a companion publication to NIST SP 800-16 Rev. 1.

SP 800-53 Rev. 4: Provides a catalog of security and privacy controls for federal information systems and a process for selecting controls (Rev. 5 pending).

SP 800-53A Rev. 4: Provides a set of procedures for conducting assessments of security controls and privacy controls employed within federal information systems.

SP 800-55 Rev. 1: Provides guidance on how to use metrics to determine the adequacy of in-place security controls, policies, and procedures.

SP 800-60 Vol. 1 Rev. 1: Provides guidelines for mapping types of information and information systems to security categories.

SP 800-61 Rev. 2: Provides guidelines for incident handling.

SP 800-82 Rev. 2: Provides guidance on how to secure Industrial Control Systems (ICS), including Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems, Distributed Control Systems (DCSs), and other control system configurations, such as Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs).

SP 800-84: Provides guidance on designing, developing, conducting, and evaluating test, training, and exercise (TT&E) events.

SP 800-86: Provides guidelines for integrating forensic techniques into incident response.

SP 800-88 Rev. 1: Provides guidelines for media sanitization.

SP 800-92: Provides guidelines for computer security log management.

SP 800-101 Rev. 1: Provides guidelines on mobile device forensics.

SP 800-115: Provides guidelines for information security testing and assessment.

SP 800-122: Provides guidelines for protecting the confidentiality of PII.

SP 800-123: Provides guidelines for general server security.

SP 800-124 Rev. 1: Provides guidelines for securing mobile devices.

SP 800-137: Provides guidelines for an Information Security Continuous Monitoring (ISCM) program.

SP 800-144: Provides guidelines on security and privacy in public cloud computing.

SP 800-145: Provides the NIST definition of cloud computing.

SP 800-146: Describes cloud computing benefits and issues, presents an overview of major classes of cloud technology, and provides guidelines on how organizations should consider cloud computing.

SP 800-150: Provides guidelines for establishing and participating in cyber threat information sharing relationships.

SP 800-153: Provides guidelines for securing wireless local area networks (WLANs).

SP 800-154 (Draft): Provides guidelines on data-centric system threat modeling.

SP 800-160: Provides guidelines on system security engineering.

SP 800-161: Provides guidance to federal agencies on identifying, assessing, and mitigating information and communication technology (ICT) supply chain risks at all levels of their organizations.

SP 800-162: Defines attribute-based access control (ABAC) and its considerations.

SP 800-163: Provides guidelines on vetting the security of mobile applications.

SP 800-164: Provides guidelines on hardware-rooted security in mobile devices.

SP 800-167: Provides guidelines on application whitelisting.

SP 800-175A and B: Provide guidelines for using cryptographic standards in the federal government.

SP 800-181: Describes the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) Cybersecurity Workforce Framework (NICE Framework).

SP 800-183: Describes the Internet of Things (IoT).

Note

For many of the SPs in the preceding list, you will simply need to know that the SP exists. For others, you need to understand details about the SP. Some NIST SPs will be covered in more detail later in this chapter or in other chapters. Refer to the index in this book to determine which SPs are covered in more detail.

HITRUST CSF

HITRUST is a privately held U.S. company that works with healthcare, technology, and information security leaders to establish the Common Security Framework (CSF) that can be used by all organizations that create, access, store, or exchange sensitive and/or regulated data. It was written to address the requirements of multiple regulations and standards. Version 9.1 was released in February, 2018. It is primarily used in the healthcare industry.

This framework has 14 control categories:

0.0: Information Security Management Program

1.0: Access Control

2.0: Human Resources Security

3.0: Risk Management

4.0: Security Policy

5.0: Organization of Information Security

6.0: Compliance

7.0: Asset Management

8.0: Physical and Environmental Security

9.0: Communications and Operations Management

10.0: Information Systems Acquisition, Development, and Maintenance

11.0: Information Security Incident Management

12.0: Business Continuity Management

13.0: Privacy Practices

Within each control category, objectives are defined and assigned levels based on their compliance with documented control standards.

CIS Critical Security Controls

The Center for Internet Security (CIS) released Critical Security Controls version 7 that lists 20 CIS controls. The first 5 controls eliminate the vast majority of an organization’s vulnerabilities. Implementing all 20 controls will secure an entire organization against today’s most pervasive threats. The 20 controls are as follows:

Inventory and control of hardware assets

Inventory and control of software assets

Continuous vulnerability management

Controlled use of administrative privileges

Secure configuration for hardware and software on mobile devices, laptops, workstations, and servers

Maintenance, monitoring, and analysis of audit logs

Email and web browser protections

Malware defenses

Limitation and control of network ports, protocols, and services

Data recovery capabilities

Secure configurations for network devices, such as firewalls, routers, and switches

Boundary defense

Data protection

Controlled access based on the need to know

Wireless access control

Account monitoring and control

Implement a security awareness training program

Application software security

Incident response and management

Penetration tests and red team exercises

The CIS Critical Security Controls provide a mapping of these controls to known standards, frameworks, laws, and regulations.

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) of the Treadway Commission Framework

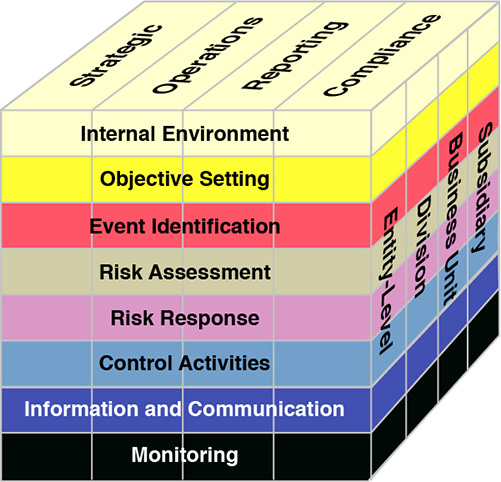

COSO is a corporate governance framework that consists of five interrelated components: control environment, risk assessment, control activities, information and communication, and monitoring activities. COBIT was derived from the COSO framework. COSO is for corporate governance; COBIT is for IT governance.

Operationally Critical Threat, Asset, and Vulnerability Evaluation (OCTAVE)

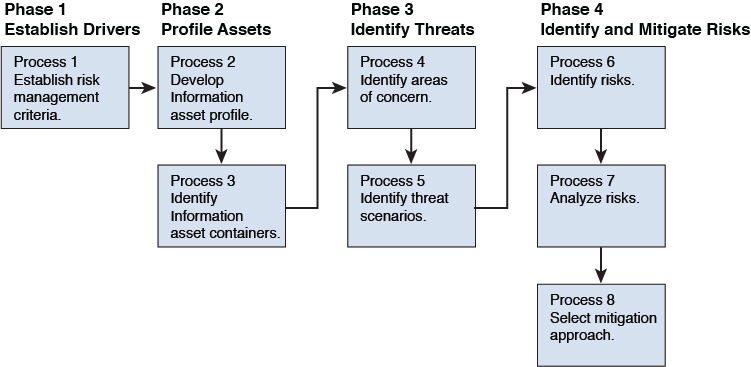

OCTAVE, which was developed by Carnegie Mellon University’s Software Engineering Institute, provides a suite of tools, techniques, and methods for risk-based information security strategic assessment and planning. Using OCTAVE, an organization implements small teams across business units and IT to work together to address the organization’s security needs. Figure 1-2 shows the phases and processes of OCTAVE Allegro, the most recent version of OCTAVE.

Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL)

ITIL is a process management development standard developed by the Office of Management and Budget in OMB Circular A-130. ITIL has five core publications: ITIL Service Strategy, ITIL Service Design, ITIL Service Transition, ITIL Service Operation, and ITIL Continual Service Improvement. These five core publications contain 26 processes. Although ITIL has a security component, it is primarily concerned with managing the service-level agreements (SLAs) between an IT department or organization and its customers. As part of the OMB Circular A-130, an independent review of security controls should be performed every three years.

Table 1-2 lists the five ITIL version 3 core publications and the 26 processes within them.

Table 1-2 ITIL v3 Core Publications and Processes

ITIL Service Strategy |

ITIL Service Design |

ITIL Service Transition |

ITIL Service Operation |

ITIL Continual Service Improvement |

Strategy Management |

Design Coordination |

Transition Planning and Support |

Event Management |

Continual Service Improvement |

Service Portfolio Management |

Service Catalogue |

Change Management |

Incident Management |

|

Financial Management for IT Services |

Service Level Management |

Service Asset and Configuration Management |

Request Fulfillment |

|

Demand Management |

Availability Management |

Release and Deployment Management |

Problem Management |

|

Business Relationship Management |

Capacity Management |

Service Validation and Testing |

Access Management |

|

|

IT Service Continuity Management |

Change Evaluation |

|

|

|

Information Security Management System |

Knowledge Management |

|

|

|

Supplier Management |

|

|

|

Six Sigma

Six Sigma is a process improvement standard that includes two project methodologies that were inspired by Deming’s Plan–Do–Check–Act cycle. The DMAIC methodology includes Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control. The DMADV methodology includes Define, Measure, Analyze, Design, and Verify. Six Sigma was designed to identify and remove defects in the manufacturing process, but can be applied to many business functions, including security.

Note

The Deming cycle is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Figures 1-3 and 1-4 show both of the Six Sigma methodologies.

Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI)

Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) is a process improvement approach that addresses three areas of interest: product and service development (CMMI for development), service establishment and management (CMMI for services), and product service and acquisition (CMMI for acquisitions). CMMI has five levels of maturity for processes: Level 1 Initial, Level 2 Managed, Level 3 Defined, Level 4 Quantitatively Managed, and Level 5 Optimizing. All processes within each level of interest are assigned one of the five levels of maturity.

CCTA Risk Analysis and Management Method (CRAMM)

CRAMM is a qualitative risk analysis and management tool developed by the UK government’s Central Computer and Telecommunications Agency (CCTA). A CRAMM review includes three steps:

Identify and value assets.

Identify threats and vulnerabilities and calculate risks.

Identify and prioritize countermeasures.

Note

No organization will implement all of the aforementioned frameworks or methodologies. Security professionals should help their organization pick the framework that best fits the needs of the organization.

Top-Down Versus Bottom-Up Approach

In a top-down approach, management initiates, supports, and directs the security program. In a bottom-up approach, staff members develop a security program prior to receiving direction and support from management. A top-down approach is much more efficient than a bottom-up approach because management’s support is one of the most important components of a security program.

Security Program Life Cycle

Any security program has a continuous life cycle and should be assessed and improved constantly. The security program life cycle includes the following steps:

Plan and Organize: Includes performing risk assessment, establishing management and steering committee, evaluating business drivers, and obtaining management approval.

Implement: Includes identifying and managing assets, managing risk, managing identity and access control, training on security and awareness, implementing solutions, assigning roles, and establishing goals.

Operate and Maintain: Includes performing audits, carrying out tasks, and managing SLAs.

Monitor and Evaluate: Includes reviewing auditing and logs, evaluating security goals, and developing improvement plans for integration into the Plan and Organize step (step 1).

Figure 1-5 shows a diagram of the security program life cycle.

Due Care and Due Diligence

Due care and due diligence are two related terms that organizations must understand as they relate to the security of the organization and its assets and data.

Due care is the standard of care that a prudent person would have exercised under the same or similar conditions. In the context of security, due care means that an organization takes reasonable measures to protect its information assets, systems, and supporting infrastructure. This includes making sure that the correct policies, procedures, and standards are in place and being followed.

Due care is all about action. Organizations must institute the appropriate protections and procedures for all organizational assets, especially intellectual property. In due care, failure to meet minimum standards and practices is considered negligent. If an organization does not take actions that a prudent person would have taken under similar circumstances, the organization is negligent.

Due diligence is the act of investigation and assessment. Organizations must institute the appropriate procedures to determine any risks to organizational assets. Due diligence then provides the information necessary to ensure that the organization practices due care. Without adequate due diligence, due care cannot occur.

Due diligence includes employee background checks, business partner credit checks, system security assessments, risk assessments, penetration tests, and disaster recovery planning and testing. NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 4, discussed earlier in this chapter, in the “Security Control Frameworks” section, provides guidance for implementing security controls that will help with due diligence.

Both due care and due diligence have bearing on the security governance and risk management process. As you can see, due diligence and due care are codependent. When due diligence occurs, organizations will recognize areas of risk. Examples include an organization determining that regular personnel do not understand basic security issues, that printed documentation is not being discarded appropriately, and that employees are accessing files to which they should not have access. When due care occurs, organizations take the areas of identified risk and implement plans to protect against the risks. For the identified due diligence examples, due care examples to implement include providing personnel security awareness training, putting procedures into place for proper destruction of printed documentation, and implementing appropriate access controls for all files.

Compliance

Compliance involves being in alignment with standards, guidelines, regulations, and/or legislation. An organization must comply with governmental laws and regulations. However, compliance with standards bodies and industry associations can be considered optional in some cases, while it is mandatory for contractual obligations (like Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard) and certification requirements (like ISO 27001).

All security professionals must understand security and privacy standards, guidelines, regulations, and laws. Usually these are industry specific, meaning that the standards, guidelines, regulations, and laws are based on the type of business the organization is involved in. A great example is the healthcare industry. Due to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), healthcare organizations must follow regulations regarding how to collect, use, store, and protect PII. Often consideration must be given to local, regional, state, federal, and international governments and bodies.

Organizations and the security professionals that they employ must determine which rules they must comply with. An organization should adopt the most strict rules to which it must comply. If rules conflict with each other, organizations must take the time to determine which rule should take precedence. This decision could be based on data type, industry type, data collection method, data usage, or individual residence of those on whom they collect PII.

Any discussion of compliance would be incomplete without a discussion of a risk management approach referred to as governance, risk management, and compliance (GRC). Governance covers core organizational activities, authority within the organization, organizational accountability, and performance measurement. Risk management identifies, analyzes, evaluates, and monitors risk. Compliance ensures that organizational activities comply with established rules. Each of the three separate objectives accepts input from and supplies input to the other objectives. The GRC relationship is shown in Figure 1-6.

As part of the discussion of compliance, security professionals must understand legislative and regulatory compliance and privacy requirements.

Contractual, Legal, Industry Standards, and Regulatory Compliance

No organization operates within a bubble. All organizations are affected by laws, regulations, and compliance requirements. Organizations must ensure that they comply with all contracts, laws, industry standards, and regulations. Security professionals must understand the laws and regulations of the country or countries they are working in and the industry within which they operate. In many cases, laws and regulations are written in a manner whereby specific actions must be taken. However, there are cases where laws and regulations leave it up to the organization to determine how to comply.

The United States and European Union both have established laws and regulations that affect organizations that do business within their area of governance. While security professionals should strive to understand laws and regulations, security professionals may not have the level of knowledge and background to fully interpret these laws and regulations to protect their organization. In these cases, security professionals should work with legal representation regarding legislative or regulatory compliance.

Note

Specific laws and regulations are discussed later, in the “Privacy” subsection of the “Legal and Regulatory Issues” section of this chapter.

Privacy Requirements Compliance

Privacy requirements compliance is primarily concerned with the confidentiality of data, particularly PII. PII is increasingly coming under attack in our modern world. Almost daily, a new company, organization, or even government entity announces that PII on customers, employees, or even government agents has been compromised. These compromises damage the reputation of the organization and also can lead to liability for damages.

Both the U.S. government and the European Union have enacted laws, regulations, and directives on the collection, handling, storage, and transmission of PII, with the goal of protecting the disclosure of this data to unauthorized entities.

Security professionals are responsible for ensuring that management understands the requirements and the possible repercussions of noncompliance. Staying up to date on the latest developments regarding PII is vital.

Legal and Regulatory Issues

The legal and regulatory issues that affect organizations today have vastly expanded with the usage of computers and networks. Gone are the days when physical security of data was the only worry. With technological advances come increasing avenues of attack. This section discusses computer crime concepts, major legal systems, licensing and intellectual property, cyber crimes and data breaches, import/export controls, trans-border data flow, and privacy.

Computer Crime Concepts

Computer crimes today are usually made possible by a victim’s carelessness. If a computer crime has occurred, proving criminal intent and causation is often difficult. Investigating and prosecuting computer crimes is made even more difficult because evidence is mostly intangible. Further affecting computer crime investigation is the fact that obtaining a trail of evidence of activities performed on a computer is hard.

Because of these computer crime issues, it is important that security professionals understand the following computer crime concepts:

Computer-assisted crime

Computer-targeted crime

Incidental computer crime

Computer prevalence crime

Hackers versus crackers

Computer-Assisted Crime

A computer-assisted crime occurs when a computer is used as a tool to help commit a crime. This type of crime could be carried out without a computer but uses the computer to make committing the crime easier. Think of it this way: Criminals can steal confidential organizational data in many different manners. This crime is possible without a computer. But when criminals use computers to help them steal confidential organizational data, then a computer-assisted crime has occurred.

Computer-Targeted Crime

A computer-targeted crime occurs when a computer is the victim of an attack that’s sole purpose is to harm the computer and its owner. This type of crime could not be carried out without a computer being used. Computer crimes that fit into this category include denial-of-service (DoS) and buffer overflow attacks.

Incidental Computer Crime

An incidental computer crime occurs when a computer is involved in a computer crime without being the victim of the attack or the attacker. A computer being used as a zombie in a botnet is part of an incidental computer crime.

Computer Prevalence Crime

A computer prevalence crime occurs due to the fact that computers are so widely used in today’s world. This type of crime occurs only because computers exist. Software piracy is an example of this type of crime.

Hackers Versus Crackers

Hacker and cracker are two terms that are often used interchangeably in media but do not actually have the same meaning. Hackers are individuals who attempt to break into secure systems to obtain knowledge about the systems and possibly use that knowledge to carry out pranks or commit crimes. Crackers, on the other hand, are individuals who attempt to break into secure systems without using the knowledge gained for any nefarious purposes.

In the security world, the terms white hat, gray hat, and black hat are more easily understood and less often confused than the terms hackers and crackers. A white hat does not have any malicious intent. A black hat has malicious intent. A gray hat is considered somewhere in the middle of the two. A gray hat will break into a system, notify the administrator of the security hole, and offer to fix the security issues for a fee.

Computer Crime Examples

Now that you understand the different categories of computer crime and the individuals that perpetuate the crimes, it is appropriate to give some examples of computer crimes that are prevalent today.

Through social engineering tactics, hackers often scare users/victims into installing fake or rogue antivirus software on their computers. Pop-up boxes tell the user that a virus infection has occurred and that by clicking the button in the pop-up box, the user can purchase and install the antivirus software to remove the virus. If the user clicks the button, he or she unknowingly infects the computer with malware. Web browsers today deploy mechanisms that allow users to block pop-up messages. However, this has the drawback of sometimes preventing wanted pop-ups. Simply configuring an exception for the valid pop-up sites is better than disabling a pop-up blocker completely.

Ransomware is a special category of software that attempts to extort money out of possible victims. One category of ransomware encrypts the user’s data until a payment is made to the attacker. Another category reports to the user that his or her computer has been used for illegal activities and that a fine must be paid to prevent prosecution. But in this case, the “fine” is paid to the attacker, posing as a government official or law enforcement agency. In many cases, malware continues to operate in the background even after the ransomware has been removed. This malware often is used to commit further financial fraud on the victim.

Scareware is a category of software that locks up a computer and warns the user that a violation of federal or international law has occurred. As part of this attack, the banner or browser redirects the user to a child pornography website. The attacker claims to be recording the user and his or her actions. The victim must pay a fine to have control of the computer returned. The line between scareware and ransomware is so fine that it is often hard to distinguish between the two.

These are only a few examples of computer attacks, and attackers are coming up with new methods every day. It is a security professional’s duty to stay aware of the newest trends in this area. If a new method of attack is discovered, security professionals should take measures to communicate with users regarding the new attack as soon as possible. In addition, security professionals should ensure that security awareness training is updated to include any new attack methods. End-user education is one of the best ways to mitigate these attacks.

Major Legal Systems

Security professionals must understand the different legal systems that are used throughout the world and the components that make up the systems.

These systems include the following:

Civil code law

Common law

Criminal law

Civil/tort law

Administrative/regulatory law

Customary law

Religious law

Mixed law

Civil Code Law

Civil code law, developed in Europe, is based on written laws. It is a rule-based law and does not rely on precedence in any way. The most common legal system in the world, civil code law does not require lower courts to follow higher court decisions.

Note

Do not confuse the civil code law of Europe with the United States civil/tort laws.

Common Law

Common law, developed in England, is based on customs and precedent because no written laws were available. Common law reflects on the morals of the people and relies heavily on precedence. In this system, the lower court must follow any precedents that exist due to higher court decisions. This type of law is still in use today in the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, and Canada.

Today, common law uses a jury-based system, which can be waived so the case is decided by a judge. Common law is divided into three systems: criminal law, civil/tort law, and administrative/regulatory law.

Criminal Law

Criminal law covers any actions that are considered harmful to others. It deals with conduct that violates public protection laws. But the prosecution must provide guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. The plaintiff is usually the civil body, such as the state or federal government, that establishes the law that is violated. In criminal law, guilty parties might be imprisoned and/or fined. Criminal law is based on common law and statutory law. Statutory law is handed down by federal, state, or local legislating bodies.

Civil/Tort Law

Civil law deals with wrongs that have been committed against an individual or organization. A defendant is liable for damages to the victim (plaintiff) if the defendant had a duty of care to the victim, breached that duty (was negligent), and was the actual cause of harm to the victim. Under civil law, the victim is entitled to seek compensatory, punitive, and statutory damages. Compensatory damages are those that compensate the victim for his losses. Punitive damages are those that are handed down by juries to punish the liable party. Statutory damages are those that are based on damages established by laws.

In civil law, the liable party has caused injury to the victim. Civil laws include economic damages, liability, negligence, intentional damage, property damage, personal damage, nuisance, and dignitary torts.

In the United States, civil law allows senior officials of an organization to be held liable for any civil wrongdoing by the organization. So if an organization is negligent, the senior officials can be pursued by any parties that were wronged.

Administrative/Regulatory Law