We find by experience (our own or another’s) what is hurtful or helpful. | ||

| --Giovanni Battista Lamperti, Vocal Wisdom (1895) | ||

I have but one lamp by which my feet are guided, and that is the lamp of experience. | ||

| --Patrick Henry, Speech before the Virginia Convention (1775) | ||

You learned in Chapter 1 why an integrated approach to process improvement may make sense for both you and your organization. In this chapter, we continue on that path and explore various aspects of an integrated approach. Specifically, we discuss what must be in place for you to think about making ongoing “continuous” improvements in an integrated manner. We address various topics such as tools and methods that are available to you, and the importance of demonstrating leadership and of having a customer and quality focus. We describe “five keys” for continuous improvement (process excellence, CMMI, lean, Six Sigma, and knowledge management) and indicate how they complement each other. We explore ways to manage continuous improvement activities and show how everyone in an organization has a role to play. Finally, we conclude with some pearls of wisdom as take-away thoughts from these first two chapters.

In many organizations (including yours, one hopes), management focuses on how to stay highly effective and how to make needed improvements. In larger organizations, you might address the need to improve by making the enterprise more integrated. Whether small or large, vital activities for continuous improvement focus on enhancing business performance across the organization. For those efforts to succeed, every employee should be aware of the rationale and goals for improvement. Continuous improvement is a process in which everyone in the organization may be expected (frequently and routinely) to participate and contribute. While major process improvement activities might be conducted by small teams, making processes better is an everyday responsibility for which everyone is accountable.

If you want your organization to succeed both now and in the future, then you need to operate in a well-orchestrated, data-driven, and process-focused manner. Your goal should be to develop and nurture a strong culture of relentless process improvement—a learning environment that is highly responsive to customers, shareholders, and employees. Organizational objectives associated with this learning environment might include these outcomes:

Establishing a culture of continuous improvement across the organization

Creating and sustaining a framework to drive business results, measured by financial performance, new-business capture rate, and customer satisfaction

Identifying, evaluating, promoting, and supporting the deployment of appropriate continuous improvement methodologies, practices, and tools, such as those currently used in (but not limited to) the lean, Six Sigma, theory of constraints, ISO, and CMMI initiatives

Identifying and sharing successful (and unsuccessful) practices[1] across the organization

Implementing a robust set of leading indicators that give advanced warning of potential problems

Being the employer of choice for employees

By realizing these objectives, an organization may improve its financial performance; attract, retain, and fully leverage the talent that it has; and be a trusted provider for its customers.

Chances are good that many of the activities that are included under the banner of “continuous improvement” have been under way in your organization for some time. Supporting policies and procedures may be in place already. Employees who provide outstanding service may be given appropriate recognition and rewards. You may use metrics to manage daily operations. Perhaps your organization invests in providing employees with the training they need to do their jobs, and in developing the leaders who will forge the way in the years ahead. It may be that the lessons learned on one program are used on subsequent programs. All of these are elements of a continuous improvement culture: process discipline, applied learning, employee recognition, collection and use of metrics, training and development, and the identification and deployment of successful practices.

To really drive business performance, however, you may need to leverage your existing efforts. Reevaluating, refocusing, reemphasizing, and communicating the combined effect of those efforts may be a key step in developing and nurturing a strong culture of continuous improvement. Often organizations will reward the heroes who have had the fortitude and wisdom to get the organization out of trouble when programs faltered in meeting their objectives. But what if the organization chose to provide equal rewards to those whose fortitude, wisdom, and leadership keep the organization out of trouble in the first place? What a concept!

Management needs to make sure that there is a general understanding of its vision for continuous improvement—why it is being pursued and how it may affect employees. The goal should be to sharpen the tools that are used to improve the organization’s operations, so that problems are addressed and their solutions enhance the business, and so that data is used to analyze and improve organizational processes. The use of such tools may produce a quantifiable financial gain for the organization. Improvement objectives must also be aligned with customer priorities and with efforts to improve earnings and cash flow. Management should willingly invest in improvement projects, but only when there is a strong business case that such investment is justified. One essential goal (to avoid a frequent need for crisis management) is to uncover the root causes of ongoing problems and to make systemic changes to processes so as to guard against the reoccurrence of those problems. This will free up the wonderful, creative talent in the workforce to focus more on value-added activities. When performance and products are aligned and equally recognized for their excellence by customers, shareholders, and employees alike, an organization will be on the road to becoming a truly world-class operation that is deeply committed to continuous improvement.

The key elements of continuous improvement include the following issues:

Understanding the tools for improvement

Nurturing a continuous improvement culture

Providing strong leadership

Linking improvement to business strategies and results

Focusing on the customer

Making quality as important as cost and schedule

Establishing criteria for larger improvement events

Often different parts of an organization (such as engineering, supply-chain management, and manufacturing) are schooled in different tools and approaches for process improvement. Perhaps you work at a site or in a department that has favored one set of methods and techniques over others. As a result, you may not be equally well acquainted with all of your options for continuous improvement. In a smaller organization, you might find that everyone follows only one approach while ignoring others.

One reason for this variation is that many process improvement approaches have their origins in specific and limited areas of the enterprise. For example, lean engineering began in the manufacturing world, as did Six Sigma. In contrast, CMMI was created from the Capability Maturity Model for Software and the Systems Engineering Capability Model—models that addressed two key aspects of the engineering development world. Your goal now should be to apply continuous improvement tools to all aspects of an operation, and irrespective of origins, to select the specific process improvement methodologies or techniques that best address the problems at hand and lead to the desired business results. That could even mean applying CMMI to manufacturing, or lean engineering to software development. Operations and service functions also follow processes that should be examined with an eye toward continuous improvement.

A culture of continuous improvement and innovation is a culture that embraces change. People at all levels in the organization routinely and frequently look for ways to improve. Because its environment is constantly changing, an organization that never changes is in danger of failing to understand the dynamic needs and desires of its customers and stakeholders. At the same time, change for the sake of change is both unsettling and counterproductive. Instead, the goal is to implement change that improves the ability of the organization to meet its business objectives. With a culture of continuous improvement, all employees (from upper management on down) know that they have a stake in the game. Every employee looks for opportunities to improve and welcome improvement suggestions from others. Everyone knows how he or she aligns with the goals of continuous improvement.[2]

Sometimes your customers—especially those who want you to succeed and improve—will establish requirements for your operations, such as having an ISO certification, demonstrating a CMMI maturity level, or developing a plan on how you intend to use lean engineering. For example, an ISO certification might be required to do business in some European countries, a CMMI appraisal at specified maturity or capability levels might be called out in an RFP to bid on a contract, or a sub-contractor on a particular job might be required by an acquirer to execute a lean engineering plan. However, the benefits of focusing on process improvement extend far beyond your need to respond to such external encouragement.

From time to time, take the opportunity to think more clearly about what it really means to “embrace change.” A culture of continuous improvement helps you to develop and maintain processes that will achieve the following goals:

Improve program success and avoid crisis management

Enable action on the root causes of persistent problems, making adjustments so that the same problems do not reappear again and again

Institutionalize learning throughout the organization

To make this cultural shift become reality, continuous improvement initiatives must outline the various changes needed at all levels in the organization: senior management, program management, functional management, program personnel, and the champions for process improvement. In a smaller organization, many of these roles may be combined—and might even be yours.

Cultural change in an organization requires top leadership at all levels to be engaged, accountable, and committed. Leaders should be ready to explain and defend from a business perspective the investment that they are making in continuous improvement. Their support must be strong, consistent, and visible to build a consensus among practitioners that the endeavor is not merely the management approach du jour. (Whatever happened to total quality management, anyway?)

Executive buy-in and support are critical to obtain resources for process improvement activities and to ensure rewards for the innovation and additional hard work required for change. When initiatives cut across organizations, executives must bridge the organizational gaps and soothe the bruised egos that inevitably appear in the course of multidisciplinary endeavors. Leadership must achieve consensus among both middle management and the practitioners; otherwise, process improvement will become a paper exercise that produces hollow artifacts and lackluster performance.

For these reasons, it is essential to get commitment from executives early and often. Help them construct the “elevator speech” they need to counter resistance from middle management.[3] Executives must “walk the talk” and understand that if they take actions that belie process improvement tenets, this seemingly subtle message will be heard just as loudly as public denigration of the program. Help them develop an ongoing communication strategy, achievable goals, and good metrics for their own performance plans that can trickle down to their direct reports. Above all, make sure that upper management is notified of early successes. These stories can be trotted out to defend the program when the first wave of cash-flow problems, schedule adjustments, or other similar crisis occurs.

Leadership continuously focuses everyone on the big-picture goals:

Processes must be best-in-class if business performance and growth demands are to be met.

The process environment must rely on measurable data to deliver on commitments to customers.

The benefits of a skilled workforce and a strong process focus are realized best when managers lead the charge. Concentrate on keeping your executives aware, involved, and excited. If you do, you will be well on your way to a successful continuous improvement program.

Improvement efforts require organizational support and the allocation of resources. Those efforts should support stated business objectives and goals. Those who advocate specific process improvement projects have the obligation to make explicit the link between those projects and the organization’s stated business strategies. If a specific process improvement activity can improve the chances of winning critical business in the future, it is more likely to be embraced.

Some improvements target cost savings; others tackle cost avoidance. Process improvement will have more success, however, if a majority of those improvements directly target cost savings. Simply put, the resources expended on a specific process improvement effort should be offset by the future savings that will result from instituting the change. A convincing business case for this should be made before starting any larger-scale process improvement effort.[4] In particular, each process improvement effort that exceeds a certain size threshold should have a project charter that provides a business case.

A successful process improvement proposal will detail which data is to be collected, how that data is to be used, and what the measure of success will be; it will make a clear business case for the change. Having good data available to support business decisions and to run programs well is a central goal of any continuous improvement initiative. Senior management may listen politely when well-meaning individuals state their fervent beliefs about why some change should be made, but it is the appropriate collection, analysis, and use of data that is likely to win approval and maintain management commitment to the activity.

In recent years, virtually all of the major process improvement initiatives have emphasized the importance of focusing on customer value and on managing customer expectations. Six Sigma, lean engineering, and CMMI, for example, share this feature.

For instance, listening to the voice of the customer (VOC) is an essential component of the Six Sigma methodology. Typically, the defects that Six Sigma projects seek to correct manifest themselves in a failure to meet a measurable customer requirement. An important aspect of any Six Sigma improvement is its impact on customer satisfaction and how it adds value to the customer by better meeting the customer requirements.

Similarly, one of the 12 overarching principles in the Lean Enterprise Model (LEM) is having a continuous focus on the customers. Within the LEM, emphasis is placed on the following concerns:

Having stable and cooperative relationships with customers and suppliers

Including customers on integrated product teams

Being proactive to understand and respond to the needs of internal and external customers

Providing insight for customers into the metrics used by suppliers

Sharing information with customers

Having customers involved in requirements generation, product design, and problem solving

Having strategies to deal with customer changes

An essential theme within the CMMI models is the identification and involvement of all key project stakeholders, where “stakeholder” is understood to mean a group or individual that is affected by or in some way accountable for the outcome of an undertaking. Stakeholders may include project members, suppliers, customers, and end users. In CMMI, Integrated Product and Process Development (IPPD) is defined as a systematic approach that achieves a timely collaboration of relevant stakeholders throughout the life of the product in an attempt to better satisfy customer needs, expectations, and requirements, including quality objectives.

In CMMI, the customer appears in many contexts. Customer needs are viewed as essential to defining quantitative process objectives. The requirements development process in CMMI is characterized as transforming customer needs into product requirements, whereas final validation of the product focuses on whether customer needs have been met. Process improvement activities are to be undertaken in part because of their effects on customer satisfaction. A part of project planning entails addressing all the commitments that have been undertaken with the customer. Information from progress reviews should be communicated to customers, as well as the status of program risks. As in the LEM, in CMMI customers should be considered for inclusion in integrated product teams. During all stages of product development, life-cycle cost issues should be brought to the attention of the customers. In all of these areas of the CMMI model, as well as in others, what customers want and need is paramount.

Having seen how Six Sigma, lean engineering, and CMMI all value the role of the customer, we must also issue a call for common sense: Anything—even a customer focus—can be overdone. For example, care must be taken when customer views are undeveloped, inconsistent, or just plain wrong. It is not a good idea to unthinkingly accept everything that the customer says is needed, and the effects of a customer’s change of mind on cost, schedule, and quality must be carefully examined. Even with these provisos, however, continuous improvement should always be undertaken (as the Six Sigma, lean engineering, and CMMI approaches indicate) with a close eye maintained on customers. Indeed, careful consideration is needed from the start regarding not just the benefits that improvement efforts might provide to a customer, but also the role a customer might play in those continuous improvement efforts.

For many years and in many business contexts, discussions about quality and the importance of an organizational focus on quality have generated strong interest. To highlight one example, for many years the U.S. automobile industry has strived to improve both the quality of its products and consumers’ recognition of that improved product quality. Clearly something still is missing, as the U.S. domestic market share in this industry continues its slide. We may surmise that this slide will be reversed only after both quality products and consumers’ recognition of quality are firmly entrenched.

Needless to say, quality does not stand alone. We are all familiar with the sign in the print shop: “Good, Fast, Cheap: Pick Any Two.” In other words, a good product with fast service will not come cheaply; a fast and cheap product will not have the highest quality; and a good product at a reduced cost may be obtained, if one is willing to be patient. Of course, it is easy for a shop owner to pronounce with authority (and advertise) that he provides his customers with all three: good, fast, and cheap. Nevertheless, such a pronouncement does not make it easier to do in the real world.

In many industries, a similar list of three items might be this: cost, schedule, and quality. In this case, it is clear that we do strive for all three: meet the financial targets, deliver the product on time, and have the end result meet the customer’s expectations for a quality product. However, on a daily basis we tend not to give the quality dimension equal emphasis. While cost and schedule issues are objects of incessant attention, aspects of product quality (including product performance, reliability, supportability, and field availability) are often the subject of less intense monitoring. In the end, a project may compromise on quality to achieve cost and schedule objectives.

In a culture characterized by continuous improvement, quality is the responsibility of everyone. Quality shortcomings are prime candidates for the scrutiny of a process improvement project. Indeed, any candidate process-improvement project should be evaluated in part based on how it affects both the quality of products and customers’ recognition of that quality. It is especially important to make sure that the processes contributing to better quality are not (easily or routinely) compromised as a result of cost and schedule pressures.

So far, we have discussed various aspects of an improvement project. Clearly, not all of the activities that relate to improvement occur in the context of a formal and organized project. If you are doing your job and collecting data to monitor your progress, and that data tells you that an adjustment is needed, you do not need a large and expensive team of experts to help you fix the problem. At the other end of the spectrum, if a problem could have a major impact on the business—one that will require study and investigation to understand both the extent of the problem and its root causes—then running a project-like activity is needed. Multi-month, multi-person activities need formal criteria to prioritize and authorize the outlay of resources.

Here is the kind of information typically required in a proposal for a large-scale process improvement event:

Current problem

Approach to improvement, including tools to be used

Resources needed

Areas to be improved

Anticipated benefits

Risk analysis

Schedule, with termination criteria

Effect on customers and other key stakeholders

Metrics to be used

Options for employee recognition

Link to business strategy

Templates that outline all of the required information are useful in planning such a project. In considering the continuum of small and large process-improvement projects, it is the larger ones that tend to need the full criteria set. For smaller improvements or in smaller organizations, just making sure that the effort and resources are consistent with the expected payoff may be sufficient.

In the past, process improvement initiatives have existed in stovepipes associated with specific techniques. That is, there were lean engineering advocates, ISO quality experts, CMMI enthusiasts, and so on. Our integrated viewpoint, however, has moved us to a more methodology-independent level. We can look across all of the tools and techniques in all of these initiatives, and select the unique set of approaches that best meets our needs.

The five keys that we discuss in this section are not keys to five separate doors; rather, it is their use in appropriate combinations that will open various doors on the path to continuous change and improvement. When improvements are undertaken using a single approach, the “big picture” for process improvement is obscured. By integrating the various tools and methodologies, we are able to address a wider array of problems than if we stayed within the process improvement box with which we happen to have the most familiarity.

From a strategic point of view, the first “key” of process excellence involves nurturing a culture of continuous improvement, while identifying and using appropriate tools and methodologies to improve your processes. The other four “keys” (discussed in Sections 2.3.2 to 2.3.5) are examples of such tools and methods (Figure 2-1).

An infrastructure for process excellence allows process knowledge to be used to improve the business. A process library holds the organization’s policies, process requirements, procedures, guidance, and related process information (e.g., templates, checklists). Most organizations will develop multiple processes to meet the needs of all the kinds of projects that they do—large or small, normal or time critical, and so forth. Guidance in applying the appropriate process in a given situation is extremely important.

Process excellence relies on the identification of both successful and unsuccessful practices, and on the use of lessons learned; these two go hand-in-hand. Suppose that some process change has been identified that, if it were more widely practiced, would bring a significant competitive advantage (via cost savings, reduced cycle time, or some other criterion). In one scenario, a successful practice (or lesson learned) is stored somewhere so that potential benefactors who want to improve their own operations can search for improvement ideas. In another scenario, a group—a committee, council, or integrated process team (IPT)—that oversees a successful practice actively identifies potential benefactors throughout the organization and “pushes” the information out to them in an effort to maximize the potential benefits. Of course, in the case of unsuccessful practices, warnings—rather than kudos—are recorded or communicated.

The best way to derive value from lessons learned and successful practices is not just to list them, but to incorporate them into the standard processes and procedures by which business is routinely conducted. This should be a central activity in any culture of continuous improvement. Those who champion improvements to standard processes should be recognized for their efforts.

To understand the effects of process improvement, process performance must be measured and monitored. While the extent to which defined processes are followed is important, the extent to which they contribute to meeting business objectives and delivering value to your customers is even more telling. When changes are made, they must be implemented and deployed correctly to ensure that they deliver their full value to the organization. Business priorities and gaps drive process improvement activities. The process monitoring infrastructure is in place to ensure that all the necessary support activities needed to realize the expected benefits occur. For instance, if you improve one process but don’t take into consideration adverse effects on enabling or dependent processes, as well as the effects of the change on users, you may actually see a reduction in business performance.[5]

Usually primary process performance indicators (such as product quality, schedule, cycle time, and productivity, and the impact that these may have on customer satisfaction and cost) are used to measure the effectiveness of a process improvement program. Improvements related to these indicators typically support the achievement of company business goals, which may include increased profitability or larger market share.

By identifying which performance indicators are to be targeted for improvement, and then selecting process improvement projects that focus on those indicators, you are in a position to begin the calculation of business value and return on investment (ROI) from the project. To quantify the benefit associated with an indicator, you need to specify an appropriate metric, such as defects per unit, hours per unit, days for the project, costs saved or costs avoided, or a customer satisfaction score. You can convert these metrics into dollar amounts, based on the value of hours saved, the amount of additional business garnered, or the amount of additional profit generated, for example. Similarly, you need to quantify the cost of the improvement activity, including purchases, development work, training, maintenance, and fees. Finally, by dividing the financial benefits by the financial costs, and then subtracting 1, you can compute the ROI. For example, if an effort cost $50,000 and had a benefit of $50,000, there would be a 0 percent ROI. By contrast, if an effort that cost $50,000 had a benefit of $100,000, the project would have a 100 percent ROI.[6]

One industry standard whose use may promote process excellence is ISO 9000. Actually, this certification comprises a family of standards that represents good management practices to ensure an organization can consistently deliver products or services that meet its customers’ quality requirements. Within the ISO 9000 family of standards, ISO 9001:2000 is the one that contains process requirements; it covers these five areas:

Quality management systems

Management responsibility

Resource management

Product realization

Measurement, analysis, and improvement

There is substantial overlap between the requirements in these five areas and the process requirements in CMMI. While some differences in coverage exist, in general we predict that an organization that meets CMMI requirements will likely meet most ISO 9001:2000 requirements, and (to a lesser extent) vice versa.

Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI), which is the principle topic of this book, comprises a framework for coordinating process improvement efforts across an enterprise and measuring and monitoring the status of those efforts. Given that we will describe CMMI in detail in Part II of this book, here we will offer only a brief exposition of this model.

The CMMI provides a basis for benchmarking the “capability” of individual processes and the “maturity” of organizational efforts relating to process. One distinctive feature of CMMI is its use of “levels” to measure both of these things: the capability of an organization in individual process areas (from capability level 0 to capability level 5, with capability level 5 being best), and an overall organizational process maturity rating (from maturity level 1 to maturity level 5, with maturity level 5 being best).

Periodic CMMI appraisals can provide a broad-brush scorecard indicating where process strengths and weaknesses exist, and which areas deserve attention in future process improvement planning. The teams that are formed to conduct a CMMI appraisal are usually led by someone from outside the organization being appraised. This must be the case when level values are assigned; the independence of the lead appraiser guards against any biased ratings. In contrast, the members of the team who come from within the organization being appraised play important roles in helping the team understand the processes within the user’s context and interpret the organization’s vocabulary. It is these team members who have sufficient knowledge of the organization to probe it for process weaknesses and strengths.

The lean engineering approach to process improvement is a result of the Lean Advancement Initiative (LAI), a U.S. consortium of government, industry, labor, and academic institutions. In the early 1990s, the U.S. Air Force began to ask whether the advances that had been made in lean-engineering automobile production in Japan could be applied to the U.S. aerospace industry. As a result, LAI was started at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1993 to help reduce the cost of producing aircraft and other aerospace products. The Lean Enterprise Model focuses on the reduction of waste to improve the flow of information and work products, and the efficient creation of value for the enterprise.

Similar to other process improvement methods, a basic premise of lean engineering is that there is always a better way to provide products and services by continuously improving operations. Managers and employees learn to question the need for every work-sequence motion, for every item of in-process stock, and for every second that people, material, or machines are idle.

A key activity in a lean engineering approach is to focus on the process steps by which “value” is added to work products. A step that moves one toward the functionality of a product or service that is valued by a customer is a “value-added” step, whereas a step that does not is “non-value-added.” A mapping of the “value stream” is created to depict all of the process steps used in creating the product, some of which may add value and some of which may not. For each step, the extent to which “value” is added to the product is determined. The central objective is to use this analysis to reduce the time during which no value is added, such as a part sitting unused for days in a queue during a manufacturing process.[7]

A complete value-stream map of a process is called a “current-state map.” To reduce the number of non-value-added steps in a process is to “eliminate waste.” It is through the elimination of waste that one tries to move from the current-state map to a “future-state vision.” [8]

Here are some key principles for any lean engineering journey:

Understand “value” from the view of a customer.

Map the value stream to make it visible to all stakeholders.

Make changes to have value “pulled” from upstream in the process rather than “pushed” to the next step.

Pursue perfection as a journey and not a destination.

For example, in a large organization it may take on the average six weeks to get an international travel request approved. In this case the traveler is the customer. A mapping of the current state for the travel approval process may show that 12 signatures are needed for international trips, and that paper is passed sequentially to 12 different individuals. Much of the time during the six weeks is taken up with the non-value-added activities of mailing the request from one location to another and having the request sit in an in-box somewhere awaiting a signature.

A future-state vision for this process may be to get a decision on the travel request within four working days, on average. Perhaps the needed signatures could be reduced from 12 to 4 without jeopardizing any needed oversight or checks or exposing the company to any unnecessary risk. Perhaps some of the signature approvals could be received concurrently instead of serially. Perhaps an electronic distribution would be speedier than relying on the company mail system. By mapping the value stream with experts and process owners and identifying the non-value-added steps, one can chart a course for improving this process.[9]

For an operation to be and stay lean, managers should frequent the venues in which value is created for the organization. They should ask questions about problems and their causes, help employees understand that they have management support for their efforts to solve the problem, and make sure everyone understands which data would be used to show that the problem has been addressed.[10]

Six Sigma is an improvement methodology developed and used by Motorola, Texas Instruments, General Electric, Allied Signal, Lockheed Martin, Honeywell, and many other companies. The popularity of the Six Sigma model is due in part to the publicity regarding former General Electric CEO Jack Welch and his commitment to achieving Six Sigma capability. The Six Sigma methodology and tools are applicable to any process, including manufacturing, services, and engineering.

Six Sigma has four major objectives: (1) maintain control of process, (2) improve constantly, (3) exceed customer expectations, and (4) add tangibly to the bottom line. This methodology brings with it several tools, such as failure modes and effect analysis (FMEA), regression analysis, process simulation, and control charts. Within the Six Sigma framework there is an explicit use of statistical tools to understand and address process variation.

One central concept is analyzing a process, measuring the number of defects that may occur, and then systematically working to determine how to improve the process so as to eliminate as much as possible the causes of defects. Defects are defined as anything outside of customer specifications. To achieve the Six Sigma goals, a process must not produce more than 3.4 defects per 1 million opportunities, where an opportunity is defined as an action with a chance for a defect.

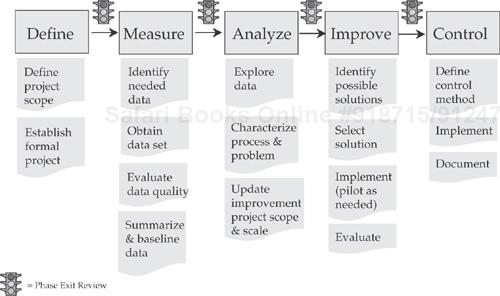

There are several Six Sigma improvement methodologies, the most widely used of which is called DMAIC (![]() ), which stands for five process steps: define, measure, analyze, improve, and control. Figure 2-2 illustrates the key Six Sigma concepts.

), which stands for five process steps: define, measure, analyze, improve, and control. Figure 2-2 illustrates the key Six Sigma concepts.

Define. The Six Sigma team defines the project’s purpose and scope, creating a project charter as a contract between the organization’s leadership and the team. The charter contains (for example) the problem statement, the business case for the project, the scope, the roles of the various team members, the milestones, and the required resources. The team obtains information on the customer (the voice of the customer [VOC]) and uses this data to develop a list of CTQs (critical to quality), CTCs (critical to cost), and CTDs (critical to delivery). More generally, we refer to all three of these components as CTX analysis. CTXs are requirements necessary for a product or service to fulfill the needs of a customer. Basic facts about the processes to be improved are captured using SIPOC (an acronym for “suppliers, inputs, processes, outputs, and customers”). In other words, SIPOC defines which inputs are needed for the process and who supplies those inputs, and which outputs are produced by the process and who makes use of those outputs.

The team may also identify “key characteristics,” which are features of a product or process whose variation may play a key role in product fit, performance, service life, manufacturability, or some other central requirement. If a key characteristic is not being met, you may need to consider a redesign, or better process control, or better inspection and testing.

Measure. The team measures the performance of the current process relative to the CTXs. The goal is to collect data relating to a process, to identify defects that are produced by the process, and to determine the possible causes of those defects. A variety of methods are available to collect, organize, and display the data. It is at this stage that the existing process is characterized and mapped, a baseline is defined, and the process capability is determined.

Analyze. The team identifies and verifies the underlying root causes of the defects produced by the existing process and quantifies their effects. Tools such as fishbone charts are useful in identifying the various causes and interdependencies at work in producing defects. Correlation and regression analysis, hypothesis testing, and statistical process control (SPC) are other methods of analyzing process data. The goal in this step is to identify sources of variation.

Improve. The team screens the potential causes of variation, reviews variable relationships, and optimizes the process. Improvement actions are identified and plans are established based on a cost–benefit analysis. Changes may be implemented in pilot tests to determine their effectiveness.

Control. The team validates the measurement system, determines the new process capability, and ensures that process controls are in place for monitoring and controlling the new process. The gains expected from the implemented changes are measured and maintained. Once the value of the new process has been documented, the results are made available to the process owner. And, of course, the team celebrates its success.

One way to think about Six Sigma, and its relationship with lean engineering and CMMI, is to focus on three key, interconnected process features: maturity, efficiency, and control. In general terms, maturity models such as CMMI focus on the maturity and capability of processes, lean engineering focuses on process efficiency and the removal of waste, and Six Sigma addresses process control and the reduction of process variability. It should be obvious that your toolkit for continuous improvement could benefit from including tools that help with all three aspects: maturity, efficiency, and control.

The somewhat formal title of “knowledge management” (KM) means simply managing data and information for the organization to promote its value as a shared resource. The goal of KM is to make relevant organizational knowledge available to those who need it, when they need it. To accomplish this task, an organization needs to have processes and tools in place to facilitate the flow of information. The larger the organization, the more “knowledge” there is, and the more daunting the management challenge. The effective use of organizational knowledge can have many beneficial results—improved performance and competitiveness, better sharing of successful practices, and better team collaboration, to name a few.

There are many ways in which a culture of continuous learning and improvement depends on the effective management of organizational knowledge. If an important lesson learned is not known by those for whom it would be useful, prior mistakes could be repeated. If information about corporate strategic goals is not widely disseminated, business decisions could be out of alignment and might run counter to each other. If insight into customer preferences is lacking, one of the prime targets for process improvement could be misunderstood. We can facilitate continuous improvement activities by working toward the KM goal of having organizational knowledge available to people when they need it.

In many organizations, one important aspect of KM is knowledge retention. As a workforce ages and members with expert knowledge approach retirement, a challenge that emerges is the need to assure that critical knowledge is not lost to the organization. One response to this issue is simple: hire retirees back as independent contractors. While this plan can have many benefits, it is helpful to supplement it with a more comprehensive approach to the issue, including mentoring of new talent by the experts, requiring succession planning, and requiring knowledge transfer planning and execution.

Starting in Chapter 3, we will explore in detail one of the five keys to continuous improvement: CMMI. Our brief discussion here is intended to encourage current and potential CMMI users to adopt an expansive view toward continuous process improvement. You need to strive for process excellence and a culture amenable to continuous improvement by developing indicators that help you achieve your business objectives. A variety of improvement strategies are available to you in the tools and techniques offered through ISO, CMMI, lean engineering, and Six Sigma, as well as other methods. You need to look at the big picture and not just CMMI. Good management of your knowledge resources is a critical foundation for any improvement strategy.

Typically in larger organizations, multiple groups are responsible for coordinating continuous improvement. Their objective is to define and implement a coordinated and integrated approach to continuous process improvement in certain areas.[11] Such groups may have the following responsibilities:

Creating and sustaining a framework for continuous improvement that is focused on customers and quality, data driven, linked to business strategy, and tied to business results

Establishing and promoting a culture of continuous learning and improvement across the organization

Identifying, evaluating, promoting, and supporting the deployment of appropriate continuous improvement methodologies, practices, and tools, such as those currently used in (but not limited to) lean engineering, Six Sigma, ISO, and CMMI initiatives

Identifying and sharing successful practices across the organization

Establishing common definitions, methodologies, and standards for process management

Developing qualified practitioners to participate in process improvement initiatives

Developing common criteria and metrics to evaluate the viability and business benefits of process improvement initiatives

Developing and maintaining a set of leading indicators

Providing insight and recommendations to the senior staff of the organization to advance continuous improvement

Helping the practitioners apply the processes in an efficient, effective, and locally controlled way

It is critical to establish the roles and responsibilities for those individuals who will lead, train, and perform the process improvement activities. This infrastructure becomes even more crucial when the organization is approaching continuous improvement in an integrated fashion. Generally, a cadre of process champions will provide the core energy, experience, and initial sweat and blood to get process improvement off the ground. These people, however, may not represent all of the stakeholders or power centers that will have important roles in the fully integrated environment.

Be aware of the political ramifications of integrating process improvement activities when forming your process groups. Make sure that all of the organizations involved have a place at the table; their participation will help counter the idea that the initiative is “something being done to them” against their wishes. Hold open meetings and advertise the outcomes. Also, keep a sense of equity throughout the effort—everyone should share in the rewards as well as the responsibility and the work.

The steering group should not be limited to practitioners and process improvement specialists. Instead, it will prove much more effective if middle management is included and if executive management is represented or chairs the group. In this way, the process-oriented groups can adequately deal with resource and other management issues, and the process champions can lead by example. The steering group should provide a feedback mechanism for the process practitioners.

Similarly, a process group that comprises mostly managers probably will not get the nitty-gritty work done. To achieve its goals, it will need subgroups, committees, or work teams to coordinate necessary training, build better processes, maintain process assets, and perform all the other activities involved in process improvement. From the outset, make sure that sufficient resources and guidance are available to allow these groups to function reasonably autonomously. Otherwise, you’ll end up with your steering group micromanaging process improvement, and chaos waiting at the doorstep.

For both the steering group and the work teams, it is important to recognize that team development is a crucial step. It takes time for team members to get up to speed; to define and understand their roles, responsibilities, expectations, and outcomes; and to recognize and address each member’s wants and needs. Strong leadership can help steer the course through both smooth and rough waters.

Skill development is probably one of the more expensive—and more important—aspects of the infrastructure. With integrated process improvement, the required skills and training go beyond simple process definition, facilitation, and model comprehension courses; they extend into the various disciplines involved as well. Software, hardware, and systems engineers may need to be cross-trained. They certainly need to understand the fundamentals of one another’s disciplines to define effective processes that involve all three areas. Although most organizations have internal resources that can provide much of this training, others may need to look into local university courses or professional training resources. Whatever way you acquire those resources, the quality, timeliness, and relevance of the training and other skill development activities can have enormous implications for the success of your program.

One cornerstone of any continuous improvement effort is having each manager and employee understand the processes that apply to the tasks at hand, and having them perform those tasks in a manner consistent with the defined processes. Questions about the processes that you should be following may be addressed simply by reading the process documentation or by availing yourself of training courses or expert mentoring. Everyone should have an understanding of the processes they are expected to follow to do their job, including both those processes specific to their current assignment and the standard processes that everyone is to follow.

If someone in the organization finds that the current defined process is faulty, inefficient, or otherwise obstructing job performance, that person should initiate a change request or otherwise raise the issue to get the process updated. Ineffective processes on the books help no one. Often there is a necessary give-and-take between those who want elaborate processes in place to guard against potential problems and those who on a day-in, day-out basis work to get product out the door and who may find certain process requirements burdensome.[12] It is a continuous activity for all of us to constantly refine our organization’s defined processes so that they are not burdensome and are viewed as a positive force in getting the job done right.

An organization may not need a large cadre of full-time process improvement experts. While a few such people may provide needed benefit, the contrast between those who “work projects” and those who “work process” needs to evolve. In short, we need people with a sufficient amount of real-world project experiences to be leaders in the effort to improve the processes; otherwise, we put the success of the process improvement effort at risk. Some organizations are moving toward a rotation system where employees “do tours” in multiple areas to increase the competency of both those who work projects and those who work process. Of course, fundamentally, everyone in the organization should be an improver!

At the same time, to run Six Sigma projects, an organization needs Green Belts, Black Belts, and Master Black Belts. A Master Black Belt may have the training and experience to justify a nearly full-time focus on process improvement; for most people who are trained to the Green Belt or Black Belt level, however, this may be an occasional or part-time effort. Similarly, to contribute to a value-stream mapping, an organization may need knowledgeable people with an appropriate degree of understanding and experience in lean engineering. To participate on a CMMI or ISO appraisal, we need an appropriate number of lead appraisers and trainers who can help prepare and guide the activity, and then educate those who will participate in the appraisal regarding what is expected of them. Very few of these assignments require a full-time commitment. For those who in varying degrees work on activities related to continuous improvement, a community of practice (CoP) may be established to help them to share their knowledge and experiences.

As you strive to embed continuous improvement into your organizational culture, you will need to provide specific guidance to all employees—from new hires all the way to the most experienced staff. This educational effort should include the steps to be taken if an employee wishes to participate on a more formalized continuous improvement activity, the organization’s current needs in terms of process improvement skills, training options, manager approvals needed, and so on.

In this chapter, we have recommended an expansive, inclusive, and integrated approach to continuous improvement. Nevertheless, you should not assume that by becoming a CMMI expert you will have all you need to improve processes and your business.

Perhaps you are part of an organization that has performed admirably in recent years while many of your competitors have faltered. Perhaps your products are well accepted; perhaps you already have established and well-documented processes; perhaps you already enjoy a good market share and high levels of customer satisfaction. So you have been—and are—doing something right; in fact, you may be doing a lot that is right. Given this enviable position, why do you want to embark on a new effort to “continuously improve”? Why do you want to “tinker” with a profit-generating machine that is working quite well? What is the risk of change? What is wrong with the status quo?

The answers to these questions are not hard to understand: However successful you have been, you should strive to do better. To remain competitive, you may need to do better. One of the cornerstones of the continuous improvement is the link with business strategies, and a focus on business results. To lay a strong foundation for “doing better,” you should take the following steps:

Study problems that affect both your customers and your profitability

Make improvements that put your organization in a better position to obtain future business

See that the savings realized from improvement projects pay back the outlay to run those projects and, in addition, provide a significant supplemental return

Champion changes that support your doing a better job of meeting your programs’ quality, cost, and schedule objectives

We conclude this chapter with some brief practical advice, or “pearls of wisdom.” These ideas are intended to help you keep in mind some general issues as you start to learn more about CMMI.

Support an integrated structure for continuous improvement groups.

Build accountability into every step, at every level.

Manage “experts and zealots” carefully—they can sometimes raise more barriers than they overcome.

Integrate continuous improvement reviews into project management reviews and individual performance evaluations.

Capture the hearts of middle managers.

Create continuous improvement as a core competency within the organization; hire for it, recognize it, reward it.

Understand that the devil is in the details—make sure that the implementation is as strong and coherent as the vision.

Train to organizational processes so that future changes to improvement models, standards, and other facets of the improvement process will have smaller effects on the organization.

Conduct regular process appraisals that emphasize proactive improvement, replacing the audit philosophy and decreasing the fear factor.

Engage real process users who can force the process definitions to be user-friendly and to address real-world, multidisciplinary concerns.

Encourage process users to “own” their processes and take pride in using and improving them.

Employ a well-designed cost accounting system to facilitate the collection of useful process metrics data, particularly for cross-functional activities.

Make a focused, continuing effort to identify common improvement opportunities.

Use a “workshop” approach to process engineering, which can result in a tenfold increase in productivity for typical meetings.

Use pilot projects early in any effort to create an integrated process, thereby allowing for testing and fine-tuning. A good cross-section of projects gives early feedback on where improvements are needed.

Don’t try to integrate organizations that differ widely in their process capabilities or maturity levels. Work first on process basics with groups that are just starting out on the journey.

Fight the “Not invented here” syndrome. “Steal with pride” is a better motto.

Focus on the development of a straightforward and consistent method for tailoring standard processes, especially for organizations that include highly diverse project domains. Even better, organize your process assets so that “standard” processes are very close to every type of project you might encounter (such as safety-critical processes, schedule-critical processes, processes using agile or other nontraditional development methods, and legacy product maintenance).

Remember that almost any change in an integrated environment will affect other groups. John Donne was right: “No man is an island.”

Recognize that an integrated, cross-disciplinary improvement effort may identify many issues and rivalries, and you will need to find creative ways to address them.

Strive for improvements that prevent the sub-optimization of processes in a cross-disciplinary environment.

Strive for cross-disciplinary continuous improvements that yield more accurate project planning and reduced cycle time.

Work to increase the buy-in from all affected organizations as you develop an integrated approach to improvement.

Implement integrated engineering assets as part of your efforts in continuous improvement.

Now, don’t you feel wiser already? On to CMMI!

[1] You usually hear about “best practices,” right? Rich has spent several years attempting to change that terminology. In his experience, there is no such thing as a “best practice”—only practices that have shown to be useful within a specific context. That same practice could be useless or even detrimental in another context (e.g., an avionics system may benefit from formal verification, whereas a Web site that changes daily would not). Given that we are generally talking about improvement here, a case can be made for improving “good” practices to “better” ones. In any event, the term “best practice” is misleading. We prefer to use “successful” (or “unsuccessful”) to describe practices that provide useful knowledge. Unsuccessful processes and practices are as critical to understand as successful processes and practices.

[2] It is extremely important that continuous improvement advocates don’t become what Barry Boehm calls “change-averse change agents”!

[3] By an “elevator speech,” we mean a brief summary of the goals, costs, and benefits of your project. This sales pitch should be short enough to be delivered effectively in the space of an elevator ride.

[4] Many smaller improvements (e.g., removing an unneeded step from a process) should not be burdened with the task of creating a business case for such change. Having a lot of managerial requirements for simple process improvements will discourage people from making those improvements.

[5] A classic example would be improvements to a company’s ordering system that meet the stated goals, but that fail to account for how those changes affect subsequent processes. While the ordering system “improves,” the product delivery system may fail to respond to the orders in a timely manner.

[6] ROI may be expressed also as a ratio. The result of the first example stated in this manner would be 1:1 ROI, and the second would be 2:1 ROI.

[7] Three indications that an activity adds value are these: (1) The customer wants it and is willing to pay for it; (2) it changes the product or service; and (3) it is done right the first time, with no rework.

[8] Most discussions of lean engineering identify multiple categories or types of waste. Typical categories include overproduction, inventory, waiting, transportation, motion, overprocessing, defects, reprioritization, and people skill utilization. Where you find one type of waste, expect to find others; they tend to snowball!

[9] It is interesting to see how different improvement initiatives can bring different perspectives to the table. In lean engineering, frequently an inspection is viewed as a non-value-added activity, one that should be eliminated. In CMMI, software inspections are viewed as a successful practice, one that should be emulated. Hmmm, eliminate or emulate inspections?

[10] For more information about lean engineering, go to http://lean.mit.edu.

[11] Of course in a smaller organization there may be only one group or even just one person assuming the responsibilities outlined here.

[12] A good example is trade studies and the requirement to document important decisions and their rationale. Those working an effort may not want to expend the resources needed to document a decision, whereas those who inherit a program that is in trouble may wish they had a better understanding of decisions made earlier in the program’s history.