7. Landscape Photography

Tips, Tools, and Techniques to Get the Most Out of Your Landscape Photography

Landscape photography transports people in ways that other types of photos don’t. Viewers long to be where the sun set over the ocean or where the desert sun warms rock and sand. As a photographer, you get to shoot outdoors and work at the mercy of Mother Nature. A landscape shot challenges you to visualize the landscape and try to capture it with the camera. Landscape photography truly is a celebration of light, composition, and the world we live in.

In this chapter, we will explore some of the features of the EOS M that will not only improve the look of your landscape photography but also make it easier to take great shots. We’ll also explore typical scenarios and discuss methods to bring out the best in your landscape work.

Poring Over the Picture

Seattle gets a bad rap for being gray and rainy, but it’s also home to some of the greatest sunsets in the world. I’m lucky that Shilshole Bay Marina, with its west-facing view and calm bay, is just a few minutes from where I live. Capturing a nice sunset is one thing—add the water’s reflection and you get two sunsets for the price of one.

Poring Over the Picture

While I was driving through the countryside outside Seattle, my eyes caught sight of this expanse of autumn leaves. The patchy sunlight created wonderful shadows against the hillside, and the clouds were too dramatic to ignore. I pulled over, grabbed my tripod, and shot several exposures (while my family patiently waited for me to indulge my photographic compulsion).

Sharp and In Focus: Using Tripods

Throughout the previous chapters, we have concentrated on using the camera to create great images. We will continue that trend through this chapter, but there is one additional piece of equipment that is crucial in the world of landscape shooting: the tripod. Tripods are critical to your landscape work for a couple of reasons. The first relates to the time of day that you will be working. For reasons that will be explained later, the best light for most landscape work happens at sunrise and just before sunset. While this is the best time to shoot, it’s also kind of dark. That means you’ll be working with slow shutter speeds. Slow shutter speeds mean camera shake. Camera shake equals bad photos.

The second reason is also related to the amount of light that you’re gathering with your camera. When taking landscape photos, you will usually want to be working with very small apertures, as they give you lots of depth of field. This also means that, once again, you will be working with slower-than-normal shutter speeds.

Slow shutter = camera shake = bad photos.

Do you see the pattern here? The one tool in your arsenal to truly defeat the camera shake issue and ensure tack-sharp photos is a good tripod.

So what should you look for in a tripod? Well, first make sure it is sturdy enough to support your camera and any lens that you might want to use. Next, check the height of the tripod. Your day will end much better if you haven’t had to bend over all day to look through your viewfinder. Finally, think about getting a tripod that utilizes a quick-release head. This usually employs a plate that screws into the bottom of the camera and then quickly snaps into place on the tripod. This will be especially handy if you are going to move between shooting by hand and using the tripod.

Selecting the Proper ISO

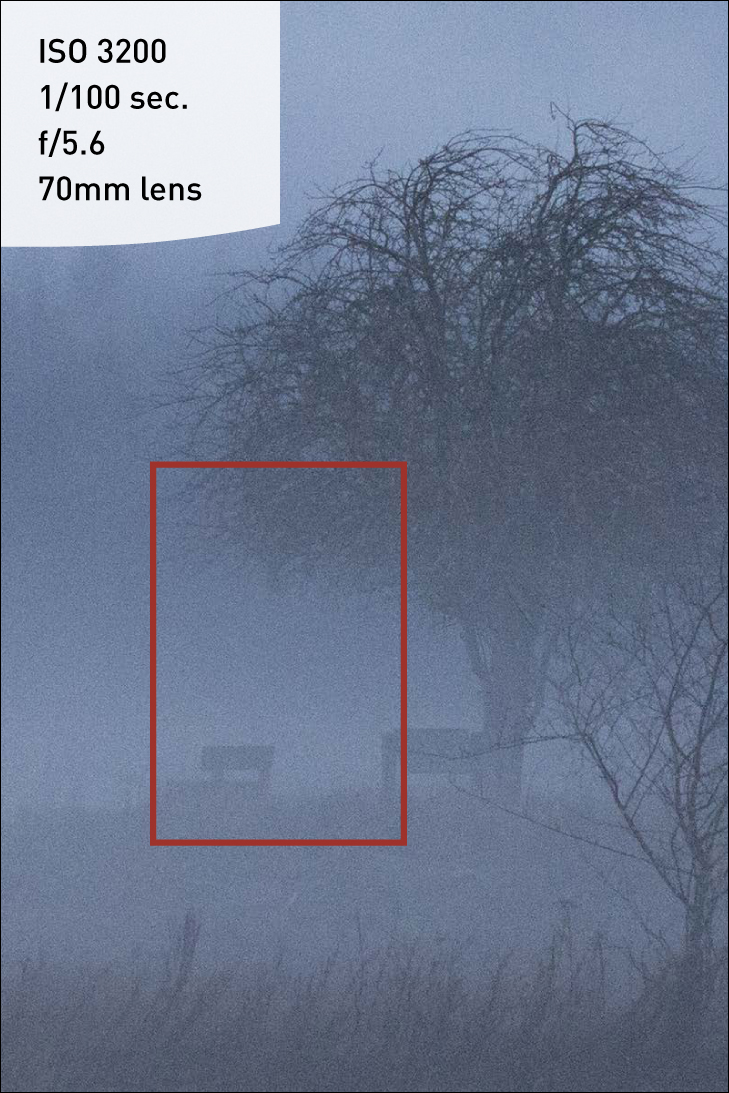

When you’re shooting most landscape scenes, the ISO is the one factor that should only be changed as a last resort. While it is easy to select a higher ISO to get a smaller aperture, the noise that it can introduce into your images can be quite harmful (Figures 7.1 and 7.2).

Figure 7.1. A high ISO setting created a lot of digital noise.

Figure 7.2. When the image is enlarged, the noise is even more apparent.

The noise not only can be visible as large grainy artifacts but can also be multicolored, which further degrades the image quality. Take a look at the image in Figure 7.2, which was taken with an ISO of 3200. It was already getting dark when I arrived, so I cranked the ISO so I’d pull out detail. Unfortunately, I ended up with a lot of noise.

Now check out another image that was taken in the same light but with a much lower ISO setting (Figures 7.3 and 7.4). As you can see, the noise levels are much lower. You’ll get blacker blacks and finer details.

Figure 7.3. By lowering the ISO to 100, I was able to avoid the noise and capture a clean image.

Figure 7.4. Zooming in shows that the noise levels for this image are almost nonexistent.

When shooting landscapes, set your ISO to the lowest possible setting at all times. Between the use of image stabilization lenses (if you are shooting handheld) and a good tripod (which I used in these examples), there should be few circumstances where you would need to shoot landscapes with anything above an ISO of 400.

Using Noise Reduction

Figures 7.1 and 7.3 were both taken with a tripod, but the image set to an ISO of 100 required a much slower shutter speed (1/14 of a second at ISO 100) than the high-ISO image (1/100 of a second at ISO 3200). There can be an issue when using a low ISO setting: The sometimes-lengthy shutter speeds can also introduce noise. This noise is a result of the heating of the camera sensor as it is being exposed to light. This effect is not visible in short exposures, but as you start shooting with shutter speeds that exceed 1 second, the level of image noise can increase. Your camera has a couple of features that you can turn on to combat noise from long exposures and high ISOs.

Setting Up Noise Reduction

1. Press the Menu button, use the Main dial to get to the fourth shooting menu, highlight the High ISO speed NR option, and press Set (A).

2. The default setting is Standard, but you may require the High setting for really high ISOs (B).

3. Press the Set button to apply the change and return to the shooting menu, and then select Long exp. noise reduction. Press the Set button to change the options (C).

4. The default setting is Auto, which will handle most scenarios. If you know you are going to be making extremely long exposures, you should probably go ahead and set it to On (D).

Selecting a White Balance

This probably seems like a no-brainer. If it’s sunny, select Daylight; if it’s overcast, choose the Shade or Cloudy setting. Those choices wouldn’t be wrong for those circumstances, but why limit yourself? Sometimes you can change the mood of the photo by selecting a white balance that doesn’t quite fit the light for the scene that you are shooting. Figure 7.5 is an example of a correct white balance. It was late afternoon and the sun was starting to move low in the sky, giving everything that warm afternoon glow. The white balance for this image was set to Daylight. But what if I want to make the scene look like it had been shot in the early morning hours? Simple—I just change the white balance to Fluorescent, which is a much cooler setting (Figure 7.6).

Figure 7.5. Using the “proper” white balance yields predictable results.

Figure 7.6. Changing the white balance to Fluorescent gives the impression that the picture was taken at a different time of day than it really was.

When you change the white balance setting on the EOS M, the LCD previews the change, so you can get an immediate idea of how the shot will appear.

Changing White Balance Settings

1. Press the Q button to bring up the Quick Control screen.

2. Tap the White Balance icon (the second one from the top on the right side of the screen), and then rotate the Main dial, press the Left/Right cross keys, or tap a setting at the bottom of the screen to change the white balance.

3. Select the white balance setting that looks most appropriate for your scene, then press the Q button to lock in your change and resume shooting.

Using the Landscape Picture Style

When shooting landscapes, I always look for great color and contrast. This is one of the reasons that so many landscape shots are taken in the early morning or during sunset. The light is much more vibrant and colorful at these times of day and adds a sense of drama to an image. You can help boost this effect, especially in the less-than-golden hours of the day, by using the Landscape picture style (Figures 7.7 and 7.8). Just as in the Landscape mode found in the Basic zone, you can set up your landscape shooting so that you capture images with increased sharpness and a slight boost in blues and greens. This style will add some pop to your landscapes without the need for additional processing in any software.

Figure 7.7. Using the Standard picture style, the colors are OK but don’t really pop.

Figure 7.8. The Landscape picture style adds sharpness, a little contrast, and more vivid color.

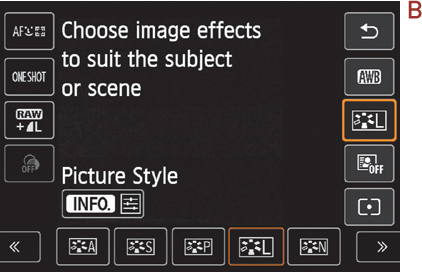

Setting Up the Landscape Picture Style

1. Press the Q button to view the Quick Control settings.

2. Tap the Picture Style button (third down on the right side) (A).

3. Use the Left/Right cross keys, the Main dial, or tap to highlight the Landscape setting (B).

4. To customize the Landscape settings (sharpness, contrast, saturation, and color tone), press the Info button and make adjustments.

5. Press the Set button to lock in your change.

If you are shooting RAW, your images will look like they have the picture style applied when you view them on the LCD, but the style will go away once you open the images in post-processing software. You will need to add the picture style back as part of your post-processing. Only JPEGs have the picture style applied as part of the final in-camera image processing. To keep the picture styles, shoot in the JPEG or RAW+JPEG mode.

Taming Bright Skies with Exposure Compensation

Balancing exposure in scenes that have a wide contrast in tonal ranges can be extremely challenging. The one thing you should try not to do is overexpose your skies to the point of blowing out your highlights (unless, of course, that is the look you are going for). It’s one thing to have white clouds, but it’s a completely different and bad thing to have no detail at all in those clouds. This usually happens when the camera is trying to gain exposure in the darker areas of the image (Figure 7.9).

Figure 7.9. The camera has done a good job of exposing the foreground, but the sky is too light and lacks detail.

The one way to tell if you have blown out your highlights is to check the Highlight Alert, or “blinkies,” feature on your camera (see the “How I Shoot” section in Chapter 4). When you take a shot where the highlights are exposed beyond the point of having any detail, that area will blink on the LCD. Is that particular area important enough to regain detail by altering your exposure? If the answer is yes, then the easiest way to go about it is to use some exposure compensation. With this feature, you can force your camera to choose an exposure that ranges, in 1/3-stop increments, from five stops over to five stops under the metered exposure (Figure 7.10).

Figure 7.10. A compensation of 2/3 stops of underexposure gave me the darker, more interesting skies that I was after.

I generally keep my camera set to –1/3 stop for most of my landscape work unless I am working with a location that is very dark or low key.

Using Exposure Compensation to Regain Detail in Highlights

1. Tap the Exposure Compensation button at the bottom of the screen.

2. Use the Main dial or tap to set the amount of over- or underexposure that you desire.

3. Take another photo.

4. If the blinkies are gone, you are good to go. If not, keep subtracting from your exposure by 1/3 of a stop until you have a good exposure in the highlights.

Shooting Beautiful Black and White Landscapes

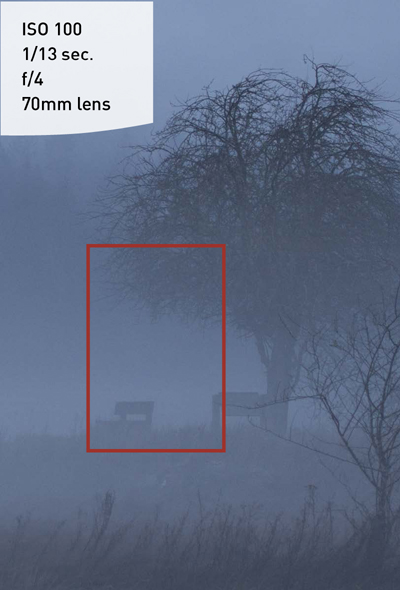

There is nothing as timeless as a beautiful black and white landscape photo. For many, it is the purest form of photography. The genre conjures up thoughts of Ansel Adams out in Yosemite Valley, capturing stunning monoliths with his 8x10 view camera. Well, just because you are shooting with a digital camera doesn’t mean you can’t create your own stunning photos using the power of the Monochrome picture style. (See the “Classic Black and White Portraits” section of Chapter 6 for instructions on setting up this feature.) Not only can you shoot in black and white, you can also apply built-in filters to lighten or darken different elements within your scene, as well as add contrast and definition.

The four filter colors are yellow, orange, red, and green. The most typically used filters in black and white photography are red and yellow. This is because the color of the filter will darken opposite colors and lighten similar colors. So if you want to darken a blue sky, you would use a yellow filter because blue is the opposite of yellow. To darken green foliage, you would use a red filter. Check out the series of shots in Figure 7.11 with different filters applied.

Figure 7.11. Adding color filter settings to the Monochrome picture style allows you to brighten or darken elements in your scene. The upper-right image has no filter applied to it. The lower-left has a green filter, and the lower-right has a red filter.

You can see that there is no real difference in contrast between the color image and the black and white image with no filter. The green filter has the effect of darkening the sky a little and giving a lighter look to the vegetation. Using the red filter makes the sky and the vegetation lighter. For this particular shot, I much prefer the look of the green filter.

Other options in the Monochrome picture style enable you to adjust the sharpness and contrast and even add some color toning to the final image. This information is also in the “Classic Black and White Portraits” section of Chapter 6. Try setting Sharpness to 5 and Contrast to 1 for landscape images. This gives an overall look to the black and white image that is reminiscent of the classic black and white films. Experiment with the various settings to find the combination that is most pleasing to you.

The Golden Light

If you ask any professional landscape photographer what their favorite time of day to shoot is, chances are they will tell you it’s the hours surrounding daybreak and sunset (Figures 7.12 and 7.13). The reason for this is that the light is coming from a very low angle to the landscape, which creates shadows and gives depth and character. There is also a quality to the light that seems cleaner and is more colorful than the light you get when shooting at midday. One thing that can dramatically improve any morning or evening shot is the presence of clouds. The sun will fill the underside of the clouds with a palette of colors and add drama to your skies.

Figure 7.12. The right subject can come alive with color during the first few minutes of sunrise.

Figure 7.13. Late afternoon sun adds drama and warmth to the subject.

Where to Focus

Large landscape scenes are fun to photograph, but they can present a problem: Where exactly do you focus when you want everything to be sharp? Since our goal is to create a great landscape photo, we need to concentrate on creating an image that is tack sharp, with a depth of field that renders great focus throughout the scene.

I have already stressed the importance of a good tripod when shooting landscapes. The tripod lets you concentrate on the aperture portion of the exposure without worrying about how long your shutter will be open. This is because the tripod provides the stability to handle any shutter speed you might need when shooting at small apertures. I find that for most of my landscape work I set my camera to Aperture Priority mode and the ISO to 100 (for a clean, noise-free image).

However, shooting with the smallest aperture on your lens doesn’t necessarily mean that you will get the proper sharpness throughout your image. The real key is knowing where in the scene to focus your lens to maximize the depth of field for your chosen aperture. To do this, you must utilize something called the “hyper focal distance” of your lens.

Hyper focal distance, also referred to as HFD, is the point of focus that will give you the greatest acceptable sharpness from a point near your camera all the way out to infinity. If you combine good HFD practice with a small aperture, you will get images that are sharp to infinity.

There are a couple of ways to do this, and the one that is probably the easiest is, as you might guess, the one that is most widely used by working pros. When you have your shot all set up and composed, focus on an object that is about one-third of the distance into your frame (Figure 7.14). It is usually pretty close to the proper distance and will render favorable results.

Figure 7.14. To get maximum focus from near to far, the focus was set one-third of the way into the image, on the line of trees along the bottom. Using this point of focus with an aperture of f/14 gave me a sharply focused image, from the trees to the distant hills.

One thing to remember is that as your lens gets wider in focal length, your HFD will be closer to the camera position. This is because the wider the lens, the greater the depth of field you can achieve. This is yet another reason why a good wide-angle lens is indispensable to the landscape shooter.

Making Water Fluid

There’s nothing quite as satisfying for the landscape shooter as capturing a silky waterfall shot. Creating the smooth-flowing effect is as simple as adjusting your shutter speed to allow the water to be in motion while the shutter is open. The key is to have your camera on a stable platform (such as a tripod) so that you can use a shutter speed that’s long enough to work (Figure 7.15). To achieve a great effect, use a shutter speed that is at least 1/15 of a second or longer.

Figure 7.15. Using a tripod combined with a small aperture, I was able to get this 1/6-second exposure and make the water look silky smooth.

If the water is blinking on the LCD (the highlight alert; see “How I Shoot” in Chapter 4), that indicates a loss of detail in the highlights. Use the Exposure Compensation feature (as discussed earlier in this chapter) to bring details back into the waterfall.

Setting Up for a Waterfall Shot

1. Attach the camera to your tripod, then compose and focus your shot.

2. For the best quality, make sure the ISO is set to 100.

3. Using Av mode, set your aperture to the smallest opening (such as f/22).

4. Press the shutter button halfway so the camera takes a meter reading.

5. Check to see if the shutter speed is 1/15 of a second or slower.

6. Take a photo and then check the image on the LCD.

There is a possibility that you will not be able to have a shutter speed that is long enough to capture a smooth, silky effect, especially if you are shooting in bright daylight conditions. To overcome this obstacle, you need a filter for your lens—either a polarizing filter or a neutral density filter. The polarizing filter redirects wavelengths of light to create more vibrant and accurate colors, reduce reflections, and darken blue skies. It is a handy filter for landscape work. The neutral density filter is typically just a dark piece of glass that serves to darken the scene by one, two, or three stops. This allows you to use slower shutter speeds during bright conditions. Think of it as sunglasses for your camera lens.

Directing the Viewer: A Word about Composition

As a photographer, it’s your job to lead the viewer through your image. You accomplish this by utilizing the principles of composition, which is the arrangement of elements in the scene that draws the viewer’s eye through your image and holds their attention.

There is a general order in which we look at elements in a photograph. The first is brightness. The eye wants to travel to the brightest object within a scene. So if you have a bright sky, it’s probably the first place the eye will travel to. The second order of attention is sharpness. Sharp, detailed elements will get more attention than soft, blurry areas. Finally, the eye will move to vivid colors while leaving the dull, flat colors for last. It is important to know these essentials in order to grab—and keep—the viewer’s attention and then direct them through the frame.

In Figure 7.16, the eye is drawn to the bright white snow and sharp edges of Mount Rainier. From there, it is pulled toward the lightness of the sky and clouds. The eye moves around the green and curved landscape in the foreground, where it is then lifted back up to the mountain, right back to the beginning. The elements within the image all help to keep the eye moving but never leave the frame.

Figure 7.16. The composition of the elements pulls the viewer’s eyes around the image, leading from one element to the next in a circular pattern.

Rule of Thirds

There are, in fact, quite a few philosophies concerning composition. The easiest one to begin with is known as the “rule of thirds.” Using this principle, you simply divide your viewfinder into thirds by imagining two horizontal and two vertical lines that divide the frame equally.

The key to using this method of composition is to have your main subject located at or near one of the intersecting points (Figure 7.17). By placing your subject near these intersecting lines, you are giving the viewer space to move within the frame. The one thing you don’t want to do is place your subject smack dab in the middle of the frame. This is sometimes referred to as “bull’s eye” composition, and it requires the right subject matter for it to work. It’s not always wrong, but it will usually be less appealing and may not hold the viewer’s focus.

Figure 7.17. With the rule-of-thirds grid atop this image, you can see that I composed the shot so that the ferry is at the bottom-left intersection and the sky dominates the top two thirds.

On the EOS M, the grid overlay can help. This is a feature that actually places a grid over your image, dividing it into thirds, which can be of great benefit in properly composing your image. Press the Menu button, and from the first shooting menu select the Grid display option. Press Set and then choose Grid 1. (The grid doesn’t appear on the final photo.)

The other general rule of thirds deals with horizon lines. Generally speaking, you should position the horizon one third of the way up or down in the frame. Splitting the frame in half by placing your horizon in the middle of the picture is akin to placing the subject in the middle of the frame—it doesn’t lend a sense of importance to either the sky or the ground.

In Figure 7.18, I incorporated the rule of thirds by aligning the horizon in the top third of the frame, with the boats and water occupying the bottom two-thirds. In doing so, I have created a sense of depth in the image. By selecting the right lens focal length (41mm, in this instance) and the right vantage point, I was able to place my horizon line so that it puts the greatest emphasis on the subject.

Figure 7.18. Placing the horizon of this image in the top third of the frame places emphasis on the marina and water reflection below.

Advanced Techniques to Explore

This section comes with a warning attached. All of the techniques and topics up to this point have been centered on your camera. The following two sections, covering panoramas and high dynamic range (HDR) images, require you to use image-processing software to complete the photograph. They are, however, important enough that you should know how to correctly shoot for success should you choose to explore these two popular techniques.

Shooting Panoramas

If you have ever visited the Grand Canyon, you know just how large and wide open it truly is—so much so that it would be difficult to capture its splendor in just one frame. The same can be said for a mountain range or a cityscape or any extremely wide vista. There are two methods that you can use to capture the feeling of this type of scene.

The “Fake” Panorama

The first method is to shoot as wide as you can and then crop out the top and bottom portion of the frame. Panoramic images are generally two or three times wider than a normal image.

Creating a Fake Panorama

1. To create the look of a panorama, find your widest lens focal length. If you’re using the 18–55mm kit lens that came with the EOS M, it would be the 18mm setting. (If your EOS M’s kit lens was the 22mm pancake lens, 22mm is your setting.)

2. Using the guidelines discussed earlier in the chapter, compose and focus your scene, and select the smallest aperture possible.

3. Shoot your image. That’s all there is to it from a photography standpoint.

4. Then, open the image in your favorite image-processing software and crop the extraneous foreground and sky from the image, leaving you with a wide panorama of the scene.

Figure 7.19 shows an example using a photo taken near sunset.

Figure 7.19. This is a nice shot, but the clouds are not very interesting and detract from the image.

As you can see, the image was shot with a lot of headroom, which includes a large portion of the sky. It looked like a good crop at the time, but after opening it in my post-processing software I had second thoughts. I opened the Crop tool, took off the top two-thirds of the frame, and came up with a panorama that is much more dynamic and visually interesting (Figure 7.20).

Figure 7.20. Cropping adds more impact and makes for a more appealing image.

The Multiple-Image Panorama

The reason the previous method is sometimes referred to as a “fake” panorama is because it is made with a standard-size frame and then cropped down to a narrow perspective. To shoot a true panorama, you need to use either a special panorama camera that shoots a very wide frame, or the following method, which requires the combining of multiple frames.

The multiple-image pano has gained in popularity in the past few years; this is principally because of advances in image-processing software. Many software options are available now that will take multiple images, align them, and then “stitch” them into a single panoramic image. The real key to shooting a multiple-image pano is to overlap your shots by about 30 percent from one frame to the next (Figures 7.21 and 7.22).

Figure 7.21. Here you see the makings of a panorama, with four shots overlapping by about 30 percent from frame to frame.

Figure 7.22. I used Adobe Photoshop to combine all of the exposures into one large panoramic image.

It is possible to handhold the camera while capturing your images, but the best method for capturing great panoramic images is to use a tripod.

Shooting Properly for a Multiple-Image Panorama

1. Mount your camera on your tripod and make sure it is level.

2. Choose a focal length for your lens that is, ideally, somewhere between 35mm and 50mm. (I used an 18mm here, which worked well, but a wide-angle lens can distort the edges of the images, making it harder to stitch them together.)

3. In Av mode, use a very small aperture for the greatest depth of field. Take a meter reading of a bright part of the scene, and make note of it.

4. Now change your camera to Manual mode (M), and dial in the aperture and shutter speed that you obtained in the previous step.

5. Set your lens to manual focus, and then focus your lens for the area of interest using the HFD method of finding a point one-third of the way into the scene. (If you use the autofocus, you risk getting different points of focus from image to image, which will make the image stitching more difficult for the software.) If you want to use the autofocus, just remember to set the lens to MF before shooting your images.

6. While carefully panning your camera, shoot your images to cover the entire area of the scene from one end to the other, leaving a 30 percent overlap from one frame to the next.

Now that you have your series of overlapping images, you can import them into your image-processing software to stitch them together and create a single panoramic image.

Shooting High Dynamic Range (HDR) Images

One of the more recent trends in digital photography is the use of high dynamic range (HDR) to capture the full range of tonal values in your final image. Typically, when you photograph a scene that has a wide range of tones from shadows to highlights, you have to make a decision regarding which tonal values you are going to emphasize, and then adjust your exposure accordingly. This is because your camera has a limited dynamic range, at least as compared to the human eye. HDR photography allows you to capture multiple exposures for the highlights, shadows, and midtones and then combine them into a single image using software (Figures 7.23 through 7.26). A number of software applications allow you to combine the images and then perform a process called “tonemapping,” whereby the complete range of exposures is represented in a single image. I will not be covering the software applications, but I will explore the process of shooting a scene to help you render properly captured images for the HDR process. Note that using a tripod is absolutely necessary for this technique, since you need to have perfect alignment of each image when they are combined.

Figure 7.23. Underexposing will render more detail in the highlight areas of the clouds and sky.

Figure 7.24. This is the normal exposure as dictated by the camera meter.

Figure 7.25. Overexposing ensures that the darker areas are exposed to get detail in the shadows.

Figure 7.26. This is the final HDR image that was rendered from the three other exposures you see here.

(The EOS M features an HDR Backlight Control mode that’s similar to this process, but the exposures are all shot and combined into one image within the camera. See Chapter 10 for more information.)

Setting Up for Shooting an HDR Image

1. Set your ISO to 100 if possible to ensure clean, noise-free images.

2. Set your program mode to Av. During the shooting process, you will be taking three shots of the same scene, creating an overexposed image, an underexposed image, and a normal exposure. Since the camera is going to be adjusting the exposure, you want it to make changes to the shutter speed, not the aperture, so that your depth of field is consistent.

3. Set your camera file format to RAW. This is extremely important because the RAW format contains a much larger range of exposure values than a JPEG file, and the HDR software will need this information.

4. Change your shooting mode to Continuous. This will allow you to capture your exposures quickly. Even though you will be using a tripod, there is always a chance that something within your scene will be moving (like clouds or leaves). Shooting in the Continuous mode minimizes any subject movement between frames.

5. Adjust the auto exposure bracket (AEB) mode to shoot three exposures in two-stop increments. To do this, first press the Info button until you’re viewing just the settings without an image preview (A).

6. Tap the Exposure Compensation button, or, if it’s not already selected, use the cross keys to highlight it and press the Set button.

7. Turn the Main dial to the right until the AEB indicators move all the way out to –2 and +2 (B). Press the Set button to lock in your changes.

8. Press the Info button to return to a preview of the scene on the LCD.

9. Focus the camera using the manual focus method discussed earlier in the chapter, compose your shot, secure the tripod, and hold down the shutter button until the camera has fired three consecutive times.

A software program—such as Adobe Photoshop, Photomatix Pro, or Nik’s HDR Efex Pro—can now process your exposure-bracketed images into a single HDR file.

Chapter 7 Assignments

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this chapter, so it’s definitely time to put this knowledge to work in order to get familiar with these new camera settings and techniques.

Comparing depth of field: wide-angle vs. telephoto

You should practice using the hyper focal distance of your lens to maximize the depth of field. You can do this by picking a focal length to work with on your lens. If you have a zoom lens, try using the longest length. Compose your image and find an object to focus on. Set your aperture to f/22 and take a photo.

Now do the same thing with the zoom lens at its widest focal length. Use the same aperture and focus point.

Review the images and compare the depth of field when using a wide-angle focal length as opposed to a telephoto focal length. Try this again with a large aperture as well.

Applying hyper focal distance to your landscapes

Pick a scene that has objects that are near the camera position as well as something that is clearly defined in the background. Try using a wide to medium-wide focal length for this (18–35mm). Use a small aperture and focus on the object in the foreground; then recompose and take a shot. Without moving the camera position, use the object in the background as your point of focus and take another shot. Finally, find a point that is one-third of the way into the frame from near to far and use that as the focus point. Compare all of the images to see which method delivered the greatest range of depth of field.

Using the rule of thirds

With the grid display active, practice shooting while placing your main subject in one of the intersecting line locations. Then take some comparison shots with the same subject in the middle of the frame.

Share your results with the book’s Flickr group!

Join the group here: flickr.com/groups/eosmfromsnapshotstogreatshots