6

Supplier responsibility:

Part 1

Establishing the program

This chapter sets the context for “supplier responsibility” and covers the steps to establish your program.

All is connected … no one thing can change by itself (Paul Hawken).

There are probably more jobs and more job growth for corporate tree-huggers working on supply-chain issues than in any other area of the company. Because of the rapid growth in this area, unlike the previous chapter on environmental sustainability, this chapter will delve into the details of how to set up and run a “supplier responsibility” program. For this area, the word “treehugger” may not be the most appropriate because, as you will see, most of the priority issues in this space tend to be social (i.e., labor and human rights).

Setting the context

Decades ago, companies figured out that it was far cheaper to outsource their manufacturing to suppliers in “low-cost” countries. While the primary driver behind outsourcing is cheaper labor rates, many of these low-cost locations suffer from lax labor and environmental regulations and/or poor enforcement. As a result, an increasing number of companies are hiring people to monitor conditions in the factories that manufacture their products.

The most recognizable of the low-cost manufacturing countries is China. I have spent a good deal of time in China, first with Intel, and then with Apple. At the time of writing, the current Chinese minimum wage is about $200 per month (this wage has been rapidly increasing and varies by location). Compare this to the U.S. minimum wage of $7.25 per hour ($1,160 per month for a 40-hour week without overtime) and the advantage is obvious: a Chinese worker will work for less than 20% of the cost of an American worker. In other popular outsourcing countries (e.g., Vietnam, Cambodia, Philippines), the differential in labor rates is even more skewed in favor of outsourcing. This trend, combined with improving quality, flexibility, speed, and logistics, has made outsourcing to China and other hotbeds of manufacturing irresistible. The cost advantages of outsourcing are now so compelling that one could argue that it is the fiduciary responsibility of the company to use this strategy.

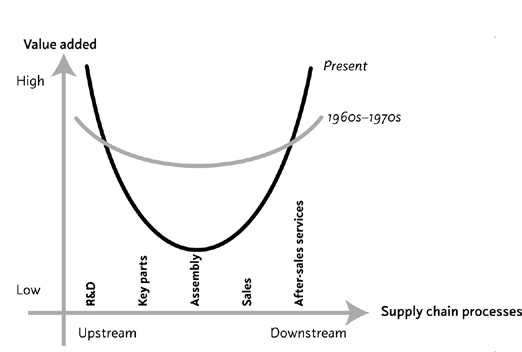

One more piece of context for the outsourcing trend is called the “smiling curve” (also called the “smiley curve”). Stan Shih, the founder of Acer (a computer company headquartered in Taiwan), first proposed the smiling curve in 1992.58 The curve shown in Figure 3 is a simple illustration of the amount of value added throughout the product lifecycle. The reason that the curve is turned up on both ends – like a smile – is that the beginning and the end of the lifecycle command higher returns on investment compared with the middle part – production. In other words, the profit margins for companies that are focused on product design or marketing are much higher than for companies focused solely on manufacturing.

Ultimately, the smiling curve makes intuitive sense: value is created from innovation. For most manufacturing processes, there is very little creativity or innovation involved. The goal is to optimize product quality against speed and cost – fairly standard stuff for most products (the exceptions to this rule are the products where manufacturing is incredibly complex, such as making semiconductors on silicon wafers).

Figure 3 The smiling curve

Source: Dedrick et al. 199959

A smart manager reacts to the smiling curve by focusing the company’s efforts on the activities that produce the highest value, or return on investment – design, marketing, and sales. This also means that the business manager’s imperative is to cut costs in the middle part of the curve, assembly or manufacturing, where the margins are the slimmest. Cost-cutting almost always leads to outsourcing manufacturing operations to low-cost locations.

While simple, this observation is a very powerful insight because it is at the heart of the outsourcing movement. If the smiling curve was the spark that lit the outsourcing movement, then globalization was the gasoline. The advent of globalization – which relaxed trade barriers, made information instantly available, logistics cheaper, and international capital more accessible – made it easier for businesses of all types to use outsourcing. As shown in Figure 3, the smiling curve has become even more pronounced in recent years. With globalization, every manufacturing business could be linked to a foreign manufacturer who could produce their designs at a fraction of the cost.

So, how does this trend create jobs for corporate treehuggers? Since the mid-1990s, when Nike became the poster child for outsourcing its production to sweatshops in Asia, public attention and corporate awareness have been focused on conditions in the supplier’s factories. The Nike story was quickly followed by related stories in the apparel industry such as child laborers making clothing promoted by Kathy Lee Gifford and the similar conditions in factories making clothes for Gap.

These high-profile cases changed everything. The reputations of companies on the right and left sides of the smiling curve that focused on design, branding, and sales, were suddenly at risk from the public outrage over poor treatment of their suppliers’ assembly-line workers. Like a post-globalization industrial revolution, activists have successfully attached these issues to global brands, forcing them to drive improvements.

At first, Nike pushed back against the activists by saying that it did not control the companies that supplied its shoes. When it was clear that this strategy was tarnishing the entire brand, the company changed course and figured out ways that it could in fact control the practices at these factories through its buying power. Similarly, when made aware of conditions in Honduran factories making clothes with her label, Kathy Lee Gifford originally said she was not involved in the production of the clothes. Later, she contacted federal authorities to investigate the allegations and began supporting laws to protect children from working in sweatshop conditions. Gap assembled a global team of auditors – over 100 people strong – to stamp out poor conditions in its supply chain, which, as you will read below, can be a tough job.

Supplier responsibility in electronics

I first encountered the supplier responsibility issue when I worked at Intel. Intel was informed that a news organization was planning an exposé on one of the company’s outsourced circuit board manufacturers in Hong Kong. Up to this point, Intel had adopted the prevalent attitude at that time that suppliers’ behaviors were their own affair – Intel’s involvement was limited to the product or service we buy from them.

Thinking that an accusation was imminent, Intel scrambled a team to visit the factory to assess the situation. There were a few gaps in their program but nothing on the scale of the apparel industry stories. Ultimately, the story never aired, but after this experience, Intel took a hard look at this issue, and decided we had to make some changes to address supplier behavior on labor and environmental issues. The program began with a training class for product quality teams – in essence, asking them to monitor conditions in supplier factories. The issue stayed quiet for several years in the electronics industry (while continuing to make headlines in the footwear and apparel industries) until the early 2000s. Around this time, the company started to observe significant increases in the number of inquiries from customers about Intel’s practices. Many of these inquiries were focused on environmental issues in the aftermath of an incident involving Sony.

In December of 2001, the government of the Netherlands seized 1.3 million Sony PlayStation® game consoles. The estimated value of the items seized was $162 million. The reason for the seizure was that there was too much cadmium in some of the cables. Sony had outsourced much of the production of the PlayStation® and a supplier installed the cadmium-tainted cables. Given the very high cost of this episode in lost product and brand reputation, Sony started its “green partner” program. This program set out to audit every supplier involved in the PlayStation® and other Sony consumer products for compliance with Sony’s code of conduct. Soon, other electronics firms followed suit and every electronics supplier experienced a huge increase in the number of customer surveys and audits focused on social and environmental issues.

During this period, I was the Director of Sustainable Development for Intel. Intel had joined the trade association, Business for Social Responsibility (BSR), and started a small group called the High Tech Coalition that included Sony and several other branded electronics firms. In early 2004, the group was meeting at Intel’s offices in Chandler, Arizona when we collectively decided to take on supplier responsibility in the electronics industry as our primary focus. The goal was to harmonize the standards and assessment methods we would all use to hold each other accountable for social and environmental issues. From this small team and lofty mission, the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition (www.EICC.info) was born. We officially announced the new organization at the 2004 BSR conference in New York City with seven member companies. Today there are more than 70 member companies in the EICC.

As the group struggled to agree on the specific standards to use within the electronics industry, it appeared that the effort might founder. Two things changed that brought the EICC to fruition:

• Birth of the Electronic Industry Code of Conduct. During this time, Dell, HP, and IBM had been in negotiations with several NGOs over shareholder proxy resolutions focused on conditions in their supply chains. These negotiations produced an agreement on a five-page “Code of Conduct.” Because this Code was the product of a multi-stakeholder agreement, the other companies in the coalition quickly approved it and it became the first version of the Electronic Industry Code of Conduct

• The iPod story. During this same time period, poor working conditions at a Chinese factory making the iPod were highlighted in a British tabloid, the Daily Mail, and the story quickly went viral. Suddenly, the industry had a “Nike problem,” with the hottest brand in the industry being called out for poor conditions in its supply chain. With this exposé, interest in the EICC soared. Apple quickly joined the group, as did a flood of other companies from across the electronics supply chain

Genesis of a supplier responsibility program

Soon after the allegations of sweatshop conditions in Chinese iPod factories, I accepted the role to create and run Apple’s supplier responsibility program. Apple was under tremendous pressure to take action and address the allegations. The scrutiny was so intense that Apple posted the job announcement for the new position for only one day because it had attracted press inquiries.

When I got to Apple, the management had already completed an audit of the factory that had been named in the press allegations as well as three others. For context, these facilities are massive; the largest has an employee population near 400,000. Apple had also worked with the leaders of these factories to address the audit findings and then issued a very candid statement that some of the allegations were true – such as long hours and poor living conditions.

On my first day, my manager handed me the four audit reports (50-plus pages each) and asked me to extract and categorize the major findings so that Apple could systematically ensure that each issue was resolved. Looking back, we were all a bit naïve about the depth and breadth of the issues we would have to tackle. There were many times that I felt overwhelmed and woefully under-resourced to deal with the social and environmental conditions in such a giant and complex supply chain.

Nonetheless, I distilled the findings from the four reports into high-, medium-, and low-priority categories and briefed the senior management on the summary. The picture was a mixed bag. The conditions were not as bad as described by the press and activists, but clearly there were areas for improvement. Soon, I was on my way to China to speak to the leaders of these four factories (a trip I would repeat at least once a quarter for the time I was at Apple). As you might imagine, these meetings could be contentious. In the end, the Apple team had the two ingredients that were needed to make a program like this successful:

• Strong executive support. The support for this program at Apple extended through the highest levels of the company

• A strong market position. Most companies are eager to work with Apple because of its large buying power and growth potential. Many suppliers were willing to take whatever actions were necessary (within reason) to secure the Apple business

After the initial crisis and intense scrutiny had eased a bit, I began the process of setting up the management systems for the program and hiring a team. There are many ways to establish a supplier responsibility program, but this chapter follows the general approach I took at Apple. While some program elements may not apply to your company, this outline can serve as a resource for you to pick and choose the attributes that fit your situation best.

A word of caution about the world of supplier responsibility: if the two attributes mentioned above – executive support and market power – are not in place or are weak within your company, you will likely need to make some compromises. Ultimately, this field is about trying to get people from other countries and cultures to conform to international standards and norms. This is a tough job in any situation, but it is a whole lot easier when you have the backing from your company and enough money flowing to the suppliers to get their attention.

Establishing your company’s code of conduct

The first question you should be able to answer is: Why do you need a code of conduct? The answer to this lies in the fact that most companies now have a global supply chain. The applicable laws and regulations for social and environmental issues vary from country to country. Most contracts already contain boilerplate stipulations that the supplier must comply with all applicable laws and regulations. But if the supplier is in a country where labor and environmental laws are inadequate or poorly enforced, the purchasing company could be exposed to liability for using sweatshops. In essence, the code of conduct establishes a consistent “floor,” or the minimum expectations for your suppliers, regardless of the locally applicable laws or enforcement.

If your company does not have a formal supplier code of conduct, start by benchmarking with others in your industry as well as reviewing your company’s own internal policies, such as business ethics, human resources policies, and EHS policies. There are also international standards for many aspects of social and environmental performance. For example, Social Accountability 8000 (SA8000)60 is a highly regarded standard for labor rights which sets out international norms for maximum working hours per week, minimum days of rest per week, the definition of child labor, and the right to collectively bargain with management, as well as other issues.

Even if your company is in another industry sector, I would recommend starting with the EICC, because it is based on internationally accepted standards and it is comprehensive. The EICC covers five main areas of conduct:

1. Labor and human rights

2. Environment

3. Health and safety

4. Ethics

5. Management systems

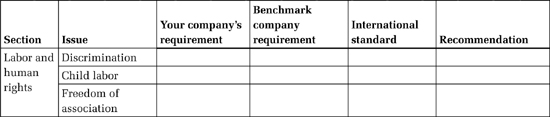

Whether you start from the EICC or another code, you will need to get executive support. The best way to approach this is to gather the codes of conduct from your benchmarking analysis and your company’s existing workplace policies, as well as any applicable international standards, into a “side-by-side” analysis. For each issue, list the policies for the company codes that you benchmarked, any relevant policy from your own company, and the applicable international standard. Based on this analysis, you should be able to quickly determine if your company has any gaps compared with other codes and standards.

Cut and paste the verbatim language from each source into the table shown in Figure 4 and compare them word for word. While this is a useful analytical tool, it is not necessarily the best tool for communication to senior management. With limited time and attention spans, senior management typically wants you to get to the bottom line as quickly as possible. With this in mind, use a table similar to Figure 4 as an analytical tool and backup reference for your summary of the recommendations for developing your company’s supplier code of conduct.

Figure 4 Side-by-side analysis for development of a code of conduct

The analysis is similar whether you are starting from no code or trying to improve an existing code. In essence it boils down to your recommendations on the standards that your company will establish for its suppliers and the rationale for your recommendation. For example, on the issue of child labor, SA8000 sets the minimum working age at 15 years with exceptions for qualified apprentice programs. The EICC also uses age 15 as the minimum working age but respects the applicable country law if it is higher than 15 (for example, the minimum working age is 16 in China). Your recommendation could be to adopt the child labor definition from EICC or SA8000, or a modification based on your company’s existing policies. In any case, the side-by-side table will allow you to reference the sources for the standards in your code.

In earlier chapters, we talked about “reading the system,” or understanding the political paradigm and reacting appropriately. When recommending a new policy for your company, you will need to understand your company’s position on the overall issue of supplier responsibility. For example, Apple was motivated to establish a leadership code based on clear, actionable standards. The company started with the EICC code and made changes that both clarified and strengthened the requirements. In contrast, other companies may choose to take a “light touch” approach by establishing only broad principles rather than a code of conduct that explicitly states the expectations for each area. For example, the Institute for Supply Management’s Principles of Sustainability and Social Responsibility outlines a series of high-level principles but stops short of setting specific standards for supplier behavior.61

Wherever your company ends up on this spectrum, it is essential that a written policy is established and ratified by the highest level appropriate in the firm. This is important because the policy is the only tangible indication of your company’s expectations. If there is no written policy, there will always be a credible argument that the expectations were not clear, and thus any performance from your suppliers could be deemed acceptable.

Laying down the law: Put the code in your contracts

In my opinion, the best practice is to include your company’s code in supplier contracts. It is important to have the code embedded in contracts, because compliance with the code will then be contractually binding for the supplier. The clause should contain language that provides your company with the right to audit the facility for conformance with the code and obligates suppliers to correct deficiencies in a timely manner. The provision should also state the possible remedies for breach (violating the code of conduct) that should include contract termination.

Apple reopened every supplier contract to add in a clause obligating the supplier to conform to the code of conduct and updated the standard contract with this clause for all new suppliers. When this clause was added into contracts, there were two camps of suppliers: those who read it and those who signed it. While this may sound flippant, many suppliers will sign almost anything to get the business. This is problematic, because it means that they have not done an assessment of their ability to comply with the new contractual requirements, and thus are unaware if they are able to comply or not. The suppliers that read the contract language and assessed their programs would often push back and negotiate for better terms, such as: advance notification before an audit; granting more time to correct deficiencies; or limiting the damages in the event of a breach. Apple spent months working through these negotiations and ended up with an array of individual agreements with suppliers. In each case, the core terms Apple insisted on were: (1) that the supplier had to adopt Apple’s code or its own code if it was deemed equivalent; (2) suppliers had to allow inspections (audits); and (3) suppliers had to commit to correcting deficiencies. In retrospect, starting the program with this contractual work was essential to the success of the program, because later on as Apple audited these facilities, there was little room to argue about the suppliers’ commitments or the standards they had agreed to meet.

Choosing which suppliers to monitor

As you set out the contractual conditions for your company’s code, one of the first issues you will encounter is which suppliers should be covered. This can be a thorny issue depending on your company management’s level of support for supplier responsibility. Start with the premise that it does not make sense to cover everyone. You can’t expect to monitor code conformance for every supplier who does business with your company. For example, your office supply vendor, your transportation company, or the landscaping company that trims the grass around your office are unlikely targets for code-conformance monitoring. These types of supplier are typically called “indirect” suppliers because they provide a product or service that is not directly related to your company’s product or service. Most supplier responsibility programs focus on direct suppliers – those companies directly involved in your company’s product or service. Establishing priorities for monitoring suppliers is critically important and involves a series of judgments outlined in the steps below:

Step 1: Create your initial target list

Apply some general criteria to filter your company’s overall supplier list. Broadly speaking, the object of this exercise is to prioritize the suppliers that are closest to your company’s business model and, by extension, your company should be able to exercise significant influence to monitor the suppliers’ behavior. Another way to look at this exercise is to identify the suppliers that could do the most harm to your company’s brand if they are committing serious code violations. There are two main criteria to determine which suppliers should be covered by your supplier oversight efforts:

• Amount of spending (this is often referred to as “spend” and expressed as a percentage of the overall spending on all suppliers) and/or the strategic value of the supplier (these could be two distinct criteria but are lumped together here because they both signify the importance of the supplier to your company)

• The likelihood that the supplier will violate the code based on generic data such as location of the supplier and/or the type of business

The most common way to identify suppliers that fall within the scope of your monitoring program is to focus on the direct suppliers that constitute 80% of your company’s total spend (direct spending only). Once you have this list, then it is appropriate to conduct a “sanity check” with your supply chain management team. This review can identify any suppliers that should be removed from the list (e.g., perhaps the supplier will be phased out) and any that should be added (e.g., a new supplier that you will be ramping up significantly or is of strong strategic importance to the company). Next, you should look at the risk of code violations posed by these suppliers. The EICC has two risk assessment tools on its website (www.eicc.info), but there are many others and you can just as easily construct your own risk tool.

To assess the potential risk of your suppliers violating your code of conduct, the first thing you have to do is to identify the specific facilities that you are buying from. You may discover that your buyers only deal with the suppliers’ sales people and may have no idea where the factories that produced the goods your company is buying are located. In this case, you will have to identify the specific facilities that supply your company. Once you have catalogued the facilities and locations, you can match up these locations against the lists of countries with known labor, human rights, or corruption problems published by Freedomhouse (www.freedomhouse.org) and Maplecroft (www.maplecroft.com) as a first approximation of the risk of violations that these facilities may pose.

Step 2: Refine your risk assessment

The next step is to refine the risk assessment process to narrow the list of supplier facilities that your program will monitor. Look at the type of work conducted by the suppliers. For example, assume that there is more risk of labor violations if the company has a large unskilled labor force with on-site worker dormitories. You can also assume that suppliers which utilize manufacturing processes entailing physical, chemical, or electrical hazards pose a heightened risk for occupational safety violations.

Step 3: Consider other known risks

Further refine your risk assessment by identifying other risk factors that may warrant scrutiny. For example, Apple discovered that suppliers located in certain countries had a higher likelihood of employing bonded laborers. Bonded labor is where workers have paid an exorbitant fee to get their job and are primarily working to pay their debt. The countries that have recently become more affluent typically import a lot of contract labor to fill lower-paid, unskilled positions that locals would not accept. In some cases, unscrupulous labor brokers will deliver workers to supplier factories who owe them (are bonded) for recruiting fees and expenses. This is a heinous practice that was found in factories with depressing frequency. After learning how to identify this practice, by insisting on interviewing contract laborers, Apple quickly figured out that the pattern was repeated in certain countries and identified these locations as an additional risk factor.

Step 4: Define the coverage of your program

Consider how many layers of the supply chain your program will cover. Most companies start their program with the suppliers with whom they have a direct relationship (tier one suppliers), but it is becoming more common to see companies diving deeper into their supply chains (tier two and beyond) to monitor code conformance. These are the suppliers to your suppliers. It becomes very difficult to approach these companies about code conformance since your company does not conduct any direct business with these suppliers.

The decision to approach tier-two+ suppliers is dependent on the company culture and the relationship to these suppliers. A typical approach is to “pass down” supplier responsibility from your direct suppliers to suppliers further down the chain. In other words, part of your conformance program is to ensure that your direct suppliers have a robust supplier responsibility program to monitor their own suppliers. Apple made the decision to monitor tier-two+ companies based on their strategic relationship. For example, if Apple directly engaged with the supplier in defining the specifications of their products, as opposed to ordering a generic commodity, then they were included in the monitoring program.

Step 5: Ask the targeted suppliers for a self-assessment

Send out a self-assessment questionnaire to the suppliers identified in steps one through four. In my experience, the self-assessment surveys can provide terrific insights into the day-to-day activities at supplier factories. The EICC has an excellent self-assessment questionnaire that delves into every aspect of its code. While self-assessments are not as reliable as audits, the results can be revealing. After reading hundreds of these, the responses range from programs that were clearly world-class to others that essentially self-declared that they had serious problems.

Be aware that it is a huge amount of work to ask your suppliers to fill out a self-assessment (for example, the EICC questionnaire is longer than 50 pages) and even more work for you and your team to evaluate the results. If you are going to use a self-assessment tool, start with a clear idea of how the data will be used. For example, would a poor score on the self-assessment lead to a supplier being put on the top of the list for an on-site audit? Does a good score mean that the facility would not be audited? The one item that is strongly recommended for any self-assessment process is to clearly indicate that the data will be verified if the facility is audited. Including this statement tends to increase the level of accuracy you can expect from the responses.

Step 6: Select suppliers for audits

Create a prioritized list of suppliers for your audit program. This task is often a mix of objective criteria (e.g., direct spend and facility locations) and subjective judgment (e.g., strategic value). This list is critically important in that it defines the scope of the audit program and the resources required. This is not a static list. You should set up a schedule by which you will review and revise your list of facilities to be audited.

Make sure that you have a process to evaluate any new suppliers that your company may hire. It is ideal to include a baseline audit or at least a self-assessment questionnaire as part of the supplier selection process. It is far more efficient and effective to identify and manage social and environmental issues as part of the supplier selection process, as opposed to doing so after the business relationship is firmly established.

This chapter covered the fundamental decisions, data requirements, and steps needed to establish a supplier responsibility program. In the next chapter we will cover the essential elements for implementing the program.