3

Setting the strategy

This chapter outlines how to design a robust corporate responsibility program, including a step-by-step approach to establishing clear strategies and objectives, as well as how to predict and manage emerging issues.

If a man knows not what harbor he seeks, any wind is the right wind (Seneca).

You have a role or are thinking about a role in corporate responsibility. What do you do first? How do you prioritize all of the issues that compose the huge scope that you must cover? How do you accomplish all that needs to be done with the limited resources that are the norm for corporate responsibility departments? In this chapter we will cover methods to establish priorities, set clear goals, and distribute the workload. We will also outline techniques to identify emerging issues to ensure your programs stay on the leading edge.

Materiality

Working in corporate responsibility can be a lot like being the plate spinner at the carnival – you are constantly moving between projects and disparate topics that are important and without your care and feeding may fail. Developing a successful corporate responsibility program requires that you start with a clear strategy based on a few critical, high-priority issues. Corporate responsibility practitioners call these “material issues” and the technique to identify these issues is a “materiality analysis.”

The starting point for any strategy is defining your priorities. While this may seem obvious and simple, in practice it can be complex and challenging, because the field of corporate responsibility is so broad and all of the issues seem important. The business axiom that applies here is: “When everything is a priority, then nothing is a priority.”

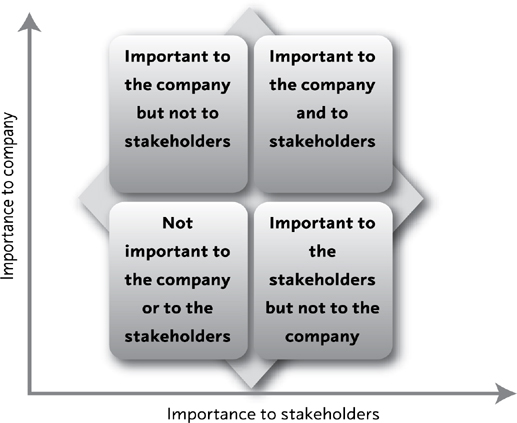

The materiality analysis is a structured process to distinguish the most important issues around which you will build your strategy. It is a relatively straightforward process of aligning your company’s priorities with the concerns of stakeholders external to your company. While there are several versions available, Figure 1 is a generic representation of the four quadrants in a standard materiality analysis. The two-by-two matrix is bound by the horizontal axis indicating increasing importance to influential stakeholders outside of your company. The vertical axis indicates increasing importance to your company’s business success. Like all two-by-two matrices, the items that end up in the top right quadrant are the areas for additional focus. Does this mean that you can ignore the CR issues in the other quadrants? No. The materiality analysis is a priority-setting tool that provides you with a small subset of opportunities that constitute the primary focus of your company’s corporate responsibility goals, investments, programs, and communications. This small set should be considered as potential leadership opportunities for your program – in other words, the issues where additional investment could return good value for your company and produce demonstrable societal benefits.

As your company and your CR programs mature and evolve, you should periodically review and revise the materiality matrix. It is wise to revisit your materiality analysis on an annual cycle or if there have been significant changes inside or outside of your company.

Figure 1 Corporate responsibility materiality matrix

The following is a list of steps for effectively applying a materiality analysis in the development of a corporate responsibility strategy:

Step 1: List the issues

Create a list and description of the universe of issues that could fall into the realm of corporate responsibility at your company. This can be a daunting task since the field is so broad, and it is difficult to have knowledge or expertise in all of the issues. A partial list of the issues that are within the scope of a corporate responsibility program includes:

• Ethical treatment of labor in the supply chain

• Corruption and bribery in the supply chain

• Product toxicity concerns

• Product energy efficiency

• Health and safety for workers and customers

• Diversity and equal opportunity

• Product packaging, take-back, and recycling

• Carbon footprint and climate protection

• Water scarcity

• Philanthropy and volunteering

• Business ethics

• Independence and diversity of the company’s governance structure

• Special risks such as nanotechnology or toxic materials

• Resource consumption

• Privacy of customer information

• Public policy and government lobbying

• Human rights

• Security practices

• Labor management relations (e.g., freedom of association and collective bargaining)

• Protecting biodiversity

• Economic impacts

• Sustainability innovations/products

• Compliance and fines

Obviously, there is a long list of issues that fall within the purview of corporate responsibility. In this initial step, gather a robust inventory of all corporate responsibility issues. A good starting point is the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)32 list of performance indicators. In addition to the GRI, review the criteria for awards and rankings (see Chapter 13) such as the Sustainable Asset Management’s (SAM) 85+ page questionnaire used to screen companies for inclusion on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index.33 These lists and surveys will provide you with insight into the corporate responsibility issues that external stakeholders are monitoring.

An efficient way to approach this step in the analysis is to hire a consultant that has experience with these analyses within your business sector. The consultant should be able to provide you with a comprehensive list of corporate responsibility issues that similar companies have faced, and help you with the prioritization process.

Step 2: Narrow your list

The next step is to thin down the list. For example, worries over childhood obesity might be a high-priority issue for a company like McDonald’s, but are not applicable to a company like Apple. Anyone with knowledge of your company’s business model can winnow the list down to the applicable issues in a couple of hours. It is often best to convene a small core team to work on this step. If you have a standing corporate responsibility committee, you could select a few people from different departments and walk through the list with them to see which issues might be eliminated before you start the prioritization process.

Step 3: Prioritize your company’s issues

Figuring out the priority corporate responsibility issues from your company’s perspective is the next step. The best method to tackle this task is to set up a series of interviews with the business leaders from each major department/business unit in your company. Target these interviews to the executive staff if you can – including the chief executive officer. Interviewing top executives can be challenging, but it is essential for a robust strategy process. Depending on your company’s structure, there will likely be a couple of management layers with whom you will need to coordinate to set up the interviews. If interviews with the executive team are not feasible, shoot for the highest level of management possible in each relevant business unit. Perhaps the top executive might delegate someone for the interviews to represent their area of responsibility.

Start by setting up meetings well in advance, with a detailed agenda. The agenda should outline the purpose of the meeting (to discuss priorities for the corporate responsibility strategy), the process you will follow, pre-read materials, the list of questions you plan to ask, and the narrowed down list of corporate responsibility issues that will be discussed. With most of the people you will interview, this preparation will make the process go much more smoothly, but expect that some people will show up to the meeting without having read the materials. For this group, you should develop and practice an “elevator speech” – a concise explanation of the purpose of the meeting, the process, and how you plan to use the results.

Expect reactions to range from clueless to eager, and adapt your interview style appropriately. Construct your interviews around open-ended questions,34 and you will gain a much greater understanding of the issues, plans, and concerns from each one of the people you interview. If you can, it is best to have someone accompany you to take notes so that you can focus on the interview. In many cases, bringing in a consultant to conduct the interviews and/or take the notes can be extremely useful because it gives you a buffer that allows you to listen and learn from the interviews. If you use a consultant, you should still participate in each of the interviews because you will not only gain first-hand knowledge of company priorities and perspectives, you will also build relationships with business leaders who are essential to the success of your corporate responsibility program.

Another method, although less advisable, for eliciting corporate responsibility priorities is a survey. Surveys can be useful, but they tend to be overused in the corporate world. While you might get more responses this way, they may not be well-considered responses. The trend in most companies is to send too many surveys to employees on a myriad of issues. Many employees feel over-surveyed and don’t think too much about the answers they give. Further, the survey taker is usually very busy, trying to clear away yet another task in their stuffed inbox, and is likely not familiar with the issues. Thus, most survey results are compilations of a series of snap judgments, and may not be representative of actual opinions.

Nonetheless, surveys can be useful tools if used judiciously. Avoid over-surveying, over-analyzing the results, or solely relying on the survey responses as the absolute truth. Surveys results must be “sanity checked” by the person/group responsible for the strategy. In other words, never feel constrained by the results of a survey – not every data point is accurate and you should corroborate the information and apply judgment when making decisions based on the results.

Step 4: Prioritize your stakeholders’ issues

The outcome of Step 3 should be a clear understanding of the priority of the applicable corporate responsibility issues from the perspective of your company’s leaders. The next step is to gauge the expectations of external stakeholders. This can be the trickiest stage of the process, as each stakeholder group may have a different agenda. Again, a consultant with experience in this process for your industry can be helpful. Seek out consultants that have experience working with your industry and have frequent interactions with NGO activists, socially responsible investors, and other stakeholders that track corporate responsibility performance in your sector, or, better yet, your company.35 This can be a wise investment since these consultants should be able to provide you with a one-stop shop for solid and credible ranking of the issues that are likely at the top of the priority list for your stakeholders.

Another approach is to establish a stakeholder advisory panel. If you have the time, inviting external stakeholders to provide input on the selection of priority issues can be extremely valuable. Their perspectives and insights can be richer and more impactful if you are able to engage directly. Stakeholder engagement, however, can be a lengthy and delicate process, as explained in Chapter 10.36

Short of a formal stakeholder panel, you can informally interview a few influential stakeholders within your network. Again, outreach and discussion will help to build relationships. The preparation is very similar to the internal interviews, but be sure to establish some ground rules up front. For example, you should set out whether the stakeholder comments are anonymous or can be attributed; develop a common understanding of how their opinions will be used as input to the strategic process; and determine how and when you will provide feedback to the stakeholders on the outcome of the process.37

Step 5: Pulling it all together

Perhaps the most important element in the development of a robust materiality analysis is a group meeting of your internal stakeholders. Owing to the breadth of the issues covered by corporate responsibility, many companies set up a council or advisory committee to guide the program. If your company has an existing council, this is the team that should be gathered together to develop the final list of priorities. If your company does not already have a corporate responsibility council, the development of a new strategy (or a strategy refresh) is a great opportunity to set one up. Similar to the executive interviews, the council membership should be made up of senior-level people from the key business units. In fact, during the interview process you could ask the executives to assign a delegate to the council. The ideal candidate is someone who is in a decision-making role within his or her business unit, has a passion for the topic of corporate responsibility, and can devote the time needed. An effective CR council is an important mechanism to help sort through and prioritize complex and sometimes ambiguous issues.38 Like a jury, people will bring in their unique perspectives, and the group conversation will spur creativity and thought that would not have happened otherwise.

To have successful meetings on establishing corporate responsibility priorities, it is essential to be well prepared. When setting up the sessions, it is best to set aside at least four hours in one of the more comfortable meeting rooms in your offices, or consider setting up an off-site location. Although off-site meetings can be more difficult and costly to set up, an off-site location helps participants to mentally untether from their day jobs, resulting in better focus and engagement. Again, send out pre-read materials with clear expectations, an agenda, and relevant background documents and be prepared for some of the participants to have skipped their homework.

I have found it best to start these meetings with a review of the objectives, the plan for the day, and – as an icebreaker39 – go around the room and ask each person to state their expectations for the meeting (capture these on a flip chart to refer back to at the end of the meeting). After this, the opening presentation should cover the results of the internal and external interviews and set out the initial findings of the materiality analysis. Keep it short so that the audience does not slide into listening mode (also known as “thinking about something else mode”) and to ensure that the audience knows that you are not giving them the answer, but rather a starting point for the discussion to follow.

In my experience, there is a huge value in hiring or assigning a facilitator for the meeting. If you have to manage the whole session, you will not be able to participate and, worse yet, the topic can appear to be a niche or even a personal agenda. Have the facilitator speak first and establish themselves as the emcee by setting out the ground rules for the session. Assign speaking roles to several people, perhaps bring in some outside speakers if the time and budget allows, and – most importantly – save plenty of time for group discussions.

Group discussions are the heart of the meeting. This is where you will get the perspectives and discussion that will establish the priorities for your program. These can be done as a facilitated dialogue with the whole group or, if you have a larger group, split the attendees into smaller breakout sessions. In either case, set out clear instructions, such as “evaluate the results of the interviews and define the top three highest priorities for the corporate responsibility program.” Draw up your list of the questions for the group discussions beforehand and ask them if they understand the expectations before you begin. If participants are not jumping in with ideas, ask someone directly or poll the group by asking each person in the room to respond to the prompt. Make sure that someone is capturing the input of the discussions on a flip chart.40

Follow up the group discussions with a summary of the key points. It is during the summary that the group’s thoughts start to crystallize into a common position. Look for and encourage the minority report – the views of the iconoclast in the room who sees things a little differently. Seek out the quiet ones who have listened a lot but not offered too much verbally. You might find that “still waters run deep” and the quieter participants – those who have spent more time listening than talking – will come up with the observation that can completely change the direction of the meeting.

The tough part is bringing it all together at the end. This is situational, and takes skilled facilitation – someone who can weave the common threads across diverse perspectives and draw out the themes that will have everyone silently nodding in agreement. Depending on how the session has progressed, the closing can range from “we have a couple of important ideas, but will need more time to work through the issues,” to “here are the priorities we have agreed to today, let’s talk about next steps.”

In my experience, I like to take notes on the common themes that emerge throughout the day. For example, at AMD, the corporate responsibility council had recognized business ethics as a material issue. Each time this issue came up though, it was clear that the group thought we already had a well-managed and -resourced program. This observation led the group to a paradigm that helped us find the signal in the noise: we added another criterion to our priority setting – issues that are “important but well covered.” This quickly surfaced a series of other issues that were “important and need more attention.” Once we agreed on this additional criterion we were able to establish a small and workable list of issues for additional focus.

Don’t rush the materiality assessment. It may take a series of meetings and follow-up discussions. As discussed above, if you can, you should engage external stakeholders in the materiality process. You should also review the draft results with the executives you previously interviewed before finalizing. The people in positions of authority over the business groups responsible for the material issues that you identify must agree with your assessment and accept their responsibility to address these issues.

For example, your process results in a recommendation that supply chain social responsibility is a high-priority issue. This conclusion is based on well-documented activist allegations of sweatshop conditions in your industry’s supply chain, coupled with a recent shift by your company to more outsourcing. Based on the data, prioritizing this issue makes sense, but it could be meaningless unless the head of your company’s procurement team buys in to the conclusion and will help drive the strategy.

One last word on the materiality meeting – or all long meetings for that matter: Serve food. The old axiom that we learn the most important life lessons in kindergarten is applicable to long meetings. When people are hungry, tired, or both, they will be cranky and will disrupt your meeting. Not only will I serve food at long meetings, but I also like to schedule plenty of breaks and, if possible, schedule these meetings on Fridays – for some reason people are just a lot happier on Fridays …

Setting the strategy

Once you have defined the list of priorities for your company’s corporate responsibility program, it is time to develop strategies for each. There are many books on developing business strategies, but I have found that effective strategy can be distilled into three main components:

1. Vision. Set out a clear vision of where you want to be in the future (this is also referred to as the future state). The vision can be “aspirational,” meaning, “we have no idea how we will ever achieve this,” or it can be literal, meaning, “we are fairly certain that we will get there.” Avoid generic vision statements like “be the world-class corporate responsibility program,” or lengthy vision statements that try to fit in everyone’s pet priority. The best vision statements are short, memorable, and actionable41

2. Objectives. Break down the steps to achieving the vision (future state) into bite-sized, achievable programs. For example, if the vision is: “Be, and be perceived as, the most responsible brand in our industry,” a supporting objective might be: “Publish a GRI-certified Grade ‘A’ report prior to the stockholders meeting.” Each objective should be assigned to an owner who has the responsibly, authority, and resources needed to achieve success. Each objective should have a deadline and be measurable with data (see KPIs below) that are reviewed on a regular basis

3. Key performance indicators (KPIs). These are the critical few “key” measures of success for each of the objectives in your strategy.42 For example, if your objective is that all tier-one suppliers should conform to your company’s code of conduct (i.e., those suppliers that work directly with your company as opposed to those who work through an intermediary), the KPI could be the number of critical non-conformance findings from audits of tier-one suppliers. It is important to understand the baseline of the KPI data, how it will be reported, and the process for review of progress toward the goal. Qualitative objectives such as “the annual corporate responsibility report was well received by influential stakeholders” can be more difficult to measure. For more subjective goals, you can establish a process of polling certain people or groups for feedback. In the next chapter, we will cover operations reviews and other forums to oversee and manage progress against goals.

Keep it simple

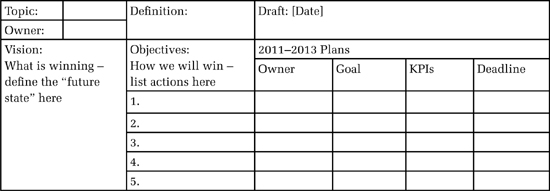

In strategy setting, I have found that the “keep it simple stupid” (KISS) rule is the best advice. People in corporate life view strategy setting as a high-value activity, so expect your company to have a defined process for establishing strategy that is the “secret sauce” in their success. While it is best to adapt to whatever paradigm your company uses for developing strategy, never lose sight of the fact that unless a strategy is understood (i.e., is actionable and memorable) and implemented by the stakeholders, it is meaningless. To keep your strategies simple, it is useful to enforce the discipline of articulating all of the elements of the strategy on a single page. The generic template in Figure 2 can be adapted and used for setting the strategies around corporate responsibility or many other issues.

Ideally, each strategy is assigned to an owner who takes responsibility for outlining the objectives (tasks) and owners, ensuring that the resources are in place and overseeing the progress against the goals. Since it is often difficult to get people to agree to take on additional work, this part can be especially challenging. A tactic that has worked for me in the past is to ghostwrite the strategy for the assigned owner, but have them present it to the appropriate review body. This makes sure that: (a) it gets done; (b) it covers the topics that you need; and (c) the owner understands it enough to present to others and gets the credit for the approach. Of course, it is preferable to have the owners develop their own strategies, but sometimes by putting in a little sweat equity, you can get the ball rolling.

Getting your strategies down on paper is all-important, but it is just the first step. In the next chapter we will cover proven tactics for implementing strategies, staying focused, and driving continuous improvement.

Figure 2 One-page strategy format

Benchmarking: The lazy person’s strategy

The human species has a fundamental “herd mentality.” We instinctually feel safer when we are doing what everyone else is doing. We feel vulnerable when we stand outside of the crowd. Perhaps this is why one of the most popular methods for approaching corporate responsibility strategy (and all strategy) is benchmarking.

Benchmarking is studying the actions of others in your field and comparing them with your own strategies. The typical ways to approach benchmarking are to: (a) identify competitors; and (b) identify the leaders in the field both within your industry (competitors) and across all sectors; then (c) identify their actions; and (d) compare their actions against your plans to identify gaps. Benchmarking is a big business for consulting firms because it is always interesting to know what others are doing on similar issues, and especially interesting to find out about leading firms.

While this can be extremely useful information for identifying gaps in your program, it should not be the only input for establishing strategy. By definition, benchmarking is backward-looking. It typically identifies what others have already done long after they have done it. For example, by the time a company is ready to disclose its strategies and results to the outside world, it has been through the planning and implementation process and is likely seeing results. Benchmarking does not reveal the emerging issues that may impact your company and your strategy; instead it shows you how others prioritized and managed issues. While benchmarking can reveal best practice and the gaps in your programs, relying on benchmarking alone can lead you to following the actions of others.

Effective strategy setting means that you have to be part fortuneteller, part iconoclast, and a first-rate risk-taker. Look around corners to identify the approaches that have not yet been tried and tested. Use benchmarking to identify what others are not doing and to generate new ideas. Find emerging threats and opportunities, and then take that leap of faith to craft a unique niche that will differentiate your company. There is a tendency in strategy development to wait for complete information and absolute certainty before taking action.

Think different: The iPhone example

When I worked at Apple, CEO Steve Jobs announced the iPhone. Smartphones were prevalent at the time of this announcement (July 2007) and the mobile phone business model was well established with a few dominant players. If Apple had relied on benchmarking and emulating the actions of leaders in the field, there would be no iPhone today.

The company motto of “think different” says it all. Mr. Jobs announced the iPhone by saying, “I don’t know about you, but I hated my phone.” He was so sure that the iPhone would change the smartphone industry forever that he said, “You will remember where you were on this day.”43

The point here is that Steve Jobs looked at a ubiquitous technology and said, “Hey, this sucks. I can make it much better.” In doing so, Apple redefined the smartphone industry and, as a result, quickly took a leadership position in a highly competitive market. While this is not a corporate responsibility example, it demonstrates that true innovation is solving problems creatively, not simply following what others have done.

Leadership entails risk-taking, which, by definition, means that you could fail. Colin Powell (former U.S. Secretary of State and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) provided some outstanding leadership tips, many of which are applicable to the business world. The Powell tip that applies here is:

Part I: Use the formula P = 40 to 70, in which P stands for the probability of success and the numbers indicate the percentage of information acquired.

Part II: Once the information is in the 40 to 70 range, go with your gut.44

Depending on the culture of your company, risk-taking can range from being encouraged to being punished. Since the definition of risk-taking involves the possibility of failure, make sure you understand the culture of your company and, to the extent you can, line up supporters in leadership roles to hedge your bets.

The crystal ball: Identifying emerging issues

Good corporate responsibility programs are excellent at identifying and prioritizing emerging issues. As discussed above, if your program’s main source of input is tracking your competitor’s actions, you will be a follower rather than a leader. But how do you uncover the emerging issues that are likely to become the next big thing and develop effective management strategies? The answer lies in developing an excellent emerging issue identification and prioritization process.

No one has a crystal ball, and all of the “futurists” are just guessing. So, if no one knows the future, what are the best ways to get out in front of issues rather than follow? There are many ways to approach this problem and none guarantees success, but I will outline some techniques that have worked in my experience.

Step 1: Issues scan

Start by defining the scope of issues you are covering in your strategy. For example, your scan could be narrowly focused on product-related environmental regulations or more broadly defined to cover the entire slate of corporate responsibility issues applicable to your company.

The issues scan is essentially a literature search of the trends and discussions within your scope. The phrase “literature search” is kind of a throwback in the Internet age – emerging issues scans involve Web searches with multiple search strings, word clouds, heat maps, social media, blogs, discussion boards, etc. – all of which can be done with internal staff, interns, or consultant support.

You may want to augment your search technique by conducting a series of interviews with people outside of your company who have a broad perspective and deep understanding of the issues at hand. For example, if the topic is environmental sustainability, talk to a green business writer from a leading media outlet, an influential NGO, or a social investment analyst. If you do interview people, design an interview guide with a few key questions that you ask consistently so that you can compare the responses. The goal is to gather information to determine which issues are being discussed by the plurality of influencers but are still nascent (which means that the issue has not yet become a government policy, widely reported in the press, or the subject of a major activist campaign). This is not an exact science and, as discussed below, the findings should be vetted in a group process.

A recent example is the emergence of water scarcity as a major sustainability issue. A few years ago, only a few influential groups were discussing this issue, while most corporate environmental programs focused on climate change. Today, water scarcity has blossomed into the “new carbon,” as an issue at the top of the environmental priority list. Another example from a few years ago was the switch from focusing on the local environmental impacts of factory emissions to the impacts throughout the lifecycle of a product.

The challenge in these “crystal ball” processes is that every issue can look like a big threat or an opportunity. Of course, not every simmering issue will boil over into a real threat or opportunity that is relevant for your program. To separate the important from the merely interesting, the issues scan is just the starting point.

Step 2: Sanity check

Once you have processed the issues scan into a few trends and key issues, the next step is to convene a group process to “sanity check” your results. While this step is not absolutely necessary, it is helpful to get other opinions into the mix and can result in adding, deleting, or editing the topics that were identified in your scan.

As part of your group session, or in advance, you should compare the trends identified in the scan against your current strategies and plans to identify any gaps. For example, if your business is making semiconductors and your scan identifies emerging concerns about the health implications of nanotechnologies, the question to examine is how your business would fare if these concerns suddenly got traction in the public consciousness. Could these concerns impact semiconductor operations? If so, does your company have a plan to cope with these issues?

Step 4: Prioritize the gaps

Once the gaps have been identified, the best way I have found to prioritize them for action is to analyze the magnitude and likelihood of the future risks or opportunities. A good way to look at this is to ask the following question: “If we did nothing more on this issue, what is the likelihood we will be impacted (positively or negatively) by the expected trend?” Then ask: “What is the potential magnitude of that impact?” By polling a group of people with knowledge of the topic on these questions, you can get a qualitative prediction (high, medium, low) of the likelihood and magnitude of potential impacts. The product of these predictions (likelihood multiplied by magnitude) yields a fair gauge of where you should consider future investments in your program.

Scenario planning

Scenario planning is a process that elegantly ties together the emerging issue scans and strategy setting. Future scenarios are created based on your issues scan and the participants role-play as if the scenario was reality. This can be an effective and fun method to shake up participants’ perspectives and paradigms. Like all group processes, it takes strong facilitation to keep the discussion on track and to extract the important lessons from the sessions.46

Intel went through an emerging issue process where the environmental team looked at the issue of climate change and saw a steeply increasing curve of public/regulatory interest (this was before the Kyoto Protocol).45 When Intel took stock of its vulnerabilities (gaps) on this issue, the team recognized that semiconductor manufacturing was one of the few industries using materials known as perfluorocarbons, or PFCs. PFCs are a class of chemicals that are very potent greenhouse gasses – in some cases more than 10,000 times the potency of carbon dioxide.

Even though there were no regulations at the time and Intel had received no public complaints about this material, future trends pointed to emerging public outrage on the climate change issue and a high likelihood that regulation would follow. The impact of a regulation to ban or severely restrict these compounds would have jeopardized multi-billion-dollar investments in manufacturing around the world.

With a high likelihood of restrictions and public outrage, a huge potential magnitude of impact (the inability to manufacture products) combined with a lack of any plan to reduce or phase out the use of PFCs, this issue quickly became a top priority. As a result, Intel assigned an internal team to work on engineering solutions and an external team to work on climate policy. Notably, these efforts resulted in the World Semiconductor Council (WSC) developing the world’s first voluntary global phase-out of greenhouse gasses. Ultimately, PFCs were regulated in several jurisdictions but, because Intel had planned ahead, it experienced no manufacturing delays and was able to collaborate with the entire industry to reduce emissions of these potent global warming gasses.

Trend spotting: Radar and sonar

While there is no single method for staying abreast of emerging trends, it is an essential capability for a corporate responsibility manager. There are two fundamental components to staying on top of emerging trends: looking outward (radar) and looking inward (sonar).

Radar

To stay on top of emerging trends and conversations on a real-time basis, subscribe to relevant blogs and e-newsletters, and follow influencers and leaders using social media tools like Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn. Some of the current leading corporate responsibility e-newsletters are: GreenBiz.com; Environmental Leader; 3BL; TriplePundit; Treehugger; Sustainable Brands; CSRwire; Grist; and Fast Company.

Establish a work-only Twitter handle and follow corporate responsibility influencers.47 Participate in significant corporate responsibility events such as the Business for Social Responsibility conference; Ceres, SRI in the Rockies; the Social Investment Forum; Net Impact; Sustainable Brands; and Fortune Brainstorm Green. The goal is to stay current and understand trends.

It is also important to apply judgment and filter the issues that show up on your radar screen. Some issues look critical but may be baseless. Raising the red flag (i.e., notifying people in your chain of command) on issues that are not well founded could result in a “cry-wolf” reputation and will not be helpful to your credibility. Alternatively, waiting for an issue to become a known threat or opportunity could result in your program being too reactive and late to act. Balancing these two scenarios to identify the critical issues and take appropriate and timely action is more art than science, but it is essential and can be managed with the techniques outlined in this chapter.

Sonar

Just as important as the radar function is the sonar function, which involves tracking your company’s trajectory. What you should look for are the changes that you can reliably predict and that could have a material impact on your CR program. If your company has a strategy office, arrange a time to speak with the staff and ask them about industry trends and the likely directions for your company.

For example, if your company may enter the wireless communications business, you should review the data and trends on the health effects of the wireless spectrum. You might also look at opportunities such as the use of wireless technology for smart grid applications that could reduce energy demand.

Another example of predicting company changes comes from my experience at Intel. With Moore’s Law driving continuous improvements in semiconductor technology, the manufacturing processes needed to make these increasingly sophisticated devices are always on the leading edge of chemistry and physics. New and potentially harmful chemicals coming into the factories and labs meant that the environment, health, and safety team needed to anticipate and mitigate potential risks on a variety of increasingly exotic materials.

Establishing a clear strategy on the right issues with appropriate staffing, resources, and oversight is the foundation of all good CR programs. By using the techniques in this chapter, you should be able forecast and prioritize key issues and design effective strategies that will achieve the vision for your CR program.