6

FUNCTIONAL PROGRAMMING

In many ways, the concepts of functional programming predate programming itself. This paradigm is strongly based on the l-calculus invented by Alonzo Church in the 1930s.

SQUARES OF INTEGERS

To explain what functional programming is, it’s best to examine some examples. Let’s investigate a simple problem: printing the squares of the first 25 integers.

In a language like Java, we might write the following:

public class Squint {

public static void main(String args[]) {

for (int i=0; i<25; i++)

System.out.println(i*i);

}

}

In a language like Clojure, which is a derivative of Lisp, and is functional, we might implement this same program as follows:

(println (take 25 (map (fn [x] (* x x)) (range))))

If you don’t know Lisp, then this might look a little strange. So let me reformat it a bit and add some comments.

(println ;___________________ Print

(take 25 ;_________________ the first 25

(map (fn [x] (* x x)) ;__ squares

(range)))) ;___________ of Integers

It should be clear that println, take, map, and range are all functions. In Lisp, you call a function by putting it in parentheses. For example, (range) calls the range function.

The expression (fn [x] (* x x)) is an anonymous function that calls the multiply function, passing its input argument in twice. In other words, it computes the square of its input.

Looking at the whole thing again, it’s best to start with the innermost function call.

• The range function returns a never-ending list of integers starting with 0.

• This list is passed into the map function, which calls the anonymous squaring function on each element, producing a new never-ending list of all the squares.

• The list of squares is passed into the take function, which returns a new list with only the first 25 elements.

• The println function prints its input, which is a list of the first 25 squares of integers.

If you find yourself terrified by the concept of never-ending lists, don’t worry. Only the first 25 elements of those never-ending lists are actually created. That’s because no element of a never-ending list is evaluated until it is accessed.

If you found all of that confusing, then you can look forward to a glorious time learning all about Clojure and functional programming. It is not my goal to teach you about these topics here.

Instead, my goal here is to point out something very dramatic about the difference between the Clojure and Java programs. The Java program uses a mutable variable—a variable that changes state during the execution of the program. That variable is i—the loop control variable. No such mutable variable exists in the Clojure program. In the Clojure program, variables like x are initialized, but they are never modified.

This leads us to a surprising statement: Variables in functional languages do not vary.

IMMUTABILITY AND ARCHITECTURE

Why is this point important as an architectural consideration? Why would an architect be concerned with the mutability of variables? The answer is absurdly simple: All race conditions, deadlock conditions, and concurrent update problems are due to mutable variables. You cannot have a race condition or a concurrent update problem if no variable is ever updated. You cannot have deadlocks without mutable locks.

In other words, all the problems that we face in concurrent applications—all the problems we face in applications that require multiple threads, and multiple processors—cannot happen if there are no mutable variables.

As an architect, you should be very interested in issues of concurrency. You want to make sure that the systems you design will be robust in the presence of multiple threads and processors. The question you must be asking yourself, then, is whether immutability is practicable.

The answer to that question is affirmative, if you have infinite storage and infinite processor speed. Lacking those infinite resources, the answer is a bit more nuanced. Yes, immutability can be practicable, if certain compromises are made.

Let’s look at some of those compromises.

SEGREGATION OF MUTABILITY

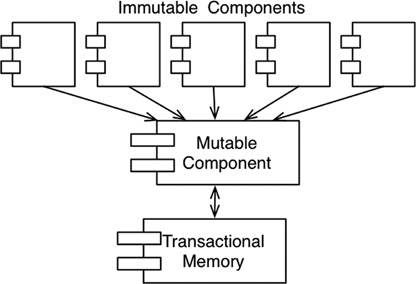

One of the most common compromises in regard to immutability is to segregate the application, or the services within the application, into mutable and immutable components. The immutable components perform their tasks in a purely functional way, without using any mutable variables. The immutable components communicate with one or more other components that are not purely functional, and allow for the state of variables to be mutated (Figure 6.1).

Since mutating state exposes those components to all the problems of concurrency, it is common practice to use some kind of transactional memory to protect the mutable variables from concurrent updates and race conditions.

Transactional memory simply treats variables in memory the same way a database treats records on disk.1 It protects those variables with a transaction- or retry-based scheme.

A simple example of this approach is Clojure’s atom facility:

(def counter (atom 0)) ; initialize counter to 0

(swap! counter inc) ; safely increment counter.

In this code, the counter variable is defined as an atom. In Clojure, an atom is a special kind of variable whose value is allowed to mutate under very disciplined conditions that are enforced by the swap! function.

The swap! function, shown in the preceding code, takes two arguments: the atom to be mutated, and a function that computes the new value to be stored in the atom. In our example code, the counter atom will be changed to the value computed by the inc function, which simply increments its argument.

The strategy used by swap! is a traditional compare and swap algorithm. The value of counter is read and passed to inc. When inc returns, the value of counter is locked and compared to the value that was passed to inc. If the value is the same, then the value returned by inc is stored in counter and the lock is released. Otherwise, the lock is released, and the strategy is retried from the beginning.

The atom facility is adequate for simple applications. Unfortunately, it cannot completely safeguard against concurrent updates and deadlocks when multiple dependent variables come into play. In those instances, more elaborate facilities can be used.

The point is that well-structured applications will be segregated into those components that do not mutate variables and those that do. This kind of segregation is supported by the use of appropriate disciplines to protect those mutated variables.

Architects would be wise to push as much processing as possible into the immutable components, and to drive as much code as possible out of those components that must allow mutation.

EVENT SOURCING

The limits of storage and processing power have been rapidly receding from view. Nowadays it is common for processors to execute billions of instructions per second and to have billions of bytes of RAM. The more memory we have, and the faster our machines are, the less we need mutable state.

As a simple example, imagine a banking application that maintains the account balances of its customers. It mutates those balances when deposit and withdrawal transactions are executed.

Now imagine that instead of storing the account balances, we store only the transactions. Whenever anyone wants to know the balance of an account, we simply add up all the transactions for that account, from the beginning of time. This scheme requires no mutable variables.

Obviously, this approach sounds absurd. Over time, the number of transactions would grow without bound, and the processing power required to compute the totals would become intolerable. To make this scheme work forever, we would need infinite storage and infinite processing power.

But perhaps we don’t have to make the scheme work forever. And perhaps we have enough storage and enough processing power to make the scheme work for the reasonable lifetime of the application.

This is the idea behind event sourcing.2 Event sourcing is a strategy wherein we store the transactions, but not the state. When state is required, we simply apply all the transactions from the beginning of time.

Of course, we can take shortcuts. For example, we can compute and save the state every midnight. Then, when the state information is required, we need compute only the transactions since midnight.

Now consider the data storage required for this scheme: We would need a lot of it. Realistically, offline data storage has been growing so fast that we now consider trillions of bytes to be small—so we have a lot of it.

More importantly, nothing ever gets deleted or updated from such a data store. As a consequence, our applications are not CRUD; they are just CR. Also, because neither updates nor deletions occur in the data store, there cannot be any concurrent update issues.

If we have enough storage and enough processor power, we can make our applications entirely immutable—and, therefore, entirely functional.

If this still sounds absurd, it might help if you remembered that this is precisely the way your source code control system works.

CONCLUSION

To summarize:

• Structured programming is discipline imposed upon direct transfer of control.

• Object-oriented programming is discipline imposed upon indirect transfer of control.

• Functional programming is discipline imposed upon variable assignment.

Each of these three paradigms has taken something away from us. Each restricts some aspect of the way we write code. None of them has added to our power or our capabilities.

What we have learned over the last half-century is what not to do.

With that realization, we have to face an unwelcome fact: Software is not a rapidly advancing technology. The rules of software are the same today as they were in 1946, when Alan Turing wrote the very first code that would execute in an electronic computer. The tools have changed, and the hardware has changed, but the essence of software remains the same.

Software—the stuff of computer programs—is composed of sequence, selection, iteration, and indirection. Nothing more. Nothing less.

1. I know... What’s a disk?

2. Thanks to Greg Young for teaching me about this concept.