27

SERVICES: GREAT AND SMALL

Service-oriented “architectures” and micro-service “architectures” have become very popular of late. The reasons for their current popularity include the following:

• Services seem to be strongly decoupled from each other. As we shall see, this is only partially true.

• Services appear to support independence of development and deployment. Again, as we shall see, this is only partially true.

SERVICE ARCHITECTURE?

First, let’s consider the notion that using services, by their nature, is an architecture. This is patently untrue. The architecture of a system is defined by boundaries that separate high-level policy from low-level detail and follow the Dependency Rule. Services that simply separate application behaviors are little more than expensive function calls, and are not necessarily architecturally significant.

This is not to say that all services should be architecturally significant. There are often substantial benefits to creating services that separate functionality across processes and platforms—whether they obey the Dependency Rule or not. It’s just that services, in and of themselves, do not define an architecture.

A helpful analogy is the organization of functions. The architecture of a monolithic or component-based system is defined by certain function calls that cross architectural boundaries and follow the Dependency Rule. Many other functions in those systems, however, simply separate one behavior from another and are not architecturally significant.

So it is with services. Services are, after all, just function calls across process and/or platform boundaries. Some of those services are architecturally significant, and some aren’t. Our interest, in this chapter, is with the former.

SERVICE BENEFITS?

The question mark in the preceding heading indicates that this section is going to challenge the current popular orthodoxy of service architecture. Let’s tackle the benefits one at a time.

THE DECOUPLING FALLACY

One of the big supposed benefits of breaking a system up into services is that services are strongly decoupled from each other. After all, each service runs in a different process, or even a different processor; therefore those services do not have access to each other’s variables. What’s more, the interface of each service must be well defined.

There is certainly some truth to this—but not very much truth. Yes, services are decoupled at the level of individual variables. However, they can still be coupled by shared resources within a processor, or on the network. What’s more, they are strongly coupled by the data they share.

For example, if a new field is added to a data record that is passed between services, then every service that operates on the new field must be changed. The services must also strongly agree about the interpretation of the data in that field. Thus those services are strongly coupled to the data record and, therefore, indirectly coupled to each other.

As for interfaces being well defined, that’s certainly true—but it is no less true for functions. Service interfaces are no more formal, no more rigorous, and no better defined than function interfaces. Clearly, then, this benefit is something of an illusion.

THE FALLACY OF INDEPENDENT DEVELOPMENT AND DEPLOYMENT

Another of the supposed benefits of services is that they can be owned and operated by a dedicated team. That team can be responsible for writing, maintaining, and operating the service as part of a dev-ops strategy. This independence of development and deployment is presumed to be scalable. It is believed that large enterprise systems can be created from dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of independently developable and deployable services. Development, maintenance, and operation of the system can be partitioned between a similar number of independent teams.

There is some truth to this belief—but only some. First, history has shown that large enterprise systems can be built from monoliths and component-based systems as well as service-based systems. Thus services are not the only option for building scalable systems.

Second, the decoupling fallacy means that services cannot always be independently developed, deployed, and operated. To the extent that they are coupled by data or behavior, the development, deployment, and operation must be coordinated.

THE KITTY PROBLEM

As an example of these two fallacies, let’s look at our taxi aggregator system again. Remember, this system knows about many taxi providers in a given city, and allows customers to order rides. Let’s assume that the customers select taxis based on a number of criteria, such as pickup time, cost, luxury, and driver experience.

We wanted our system to be scalable, so we chose to build it out of lots of little micro-services. We subdivided our development staff into many small teams, each of which is responsible for developing, maintaining, and operating a correspondingly1 small number of services.

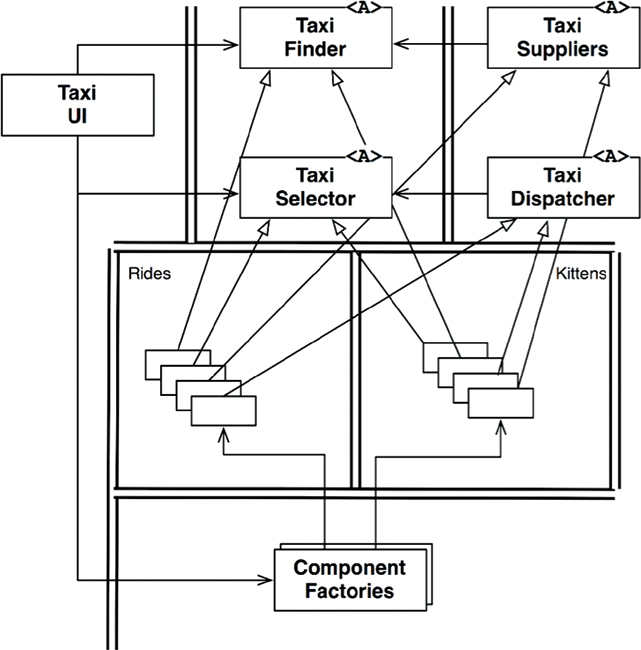

The diagram in Figure 27.1 shows how our fictitious architects arranged services to implement this application. The TaxiUI service deals with the customers, who use mobile devices to order taxis. The TaxiFinder service examines the inventories of the various TaxiSuppliers and determines which taxies are possible candidates for the user. It deposits these into a short-term data record attached to that user. The TaxiSelector service takes the user’s criteria of cost, time, luxury, and so forth, and chooses an appropriate taxi from among the candidates. It hands that taxi off to the TaxiDispatcher service, which orders the appropriate taxi.

Now let us suppose that this system has been in operation for more than a year. Our staff of developers have been happily developing new features while maintaining and operating all these services.

One bright and cheerful day, the marketing department holds a meeting with the development team. In this meeting, they announce their plans to offer a kitten delivery service to the city. Users can order kittens to be delivered to their homes or to their places of business.

The company will set up several kitten collection points across the city. When a kitten order is placed, a nearby taxi will be selected to collect a kitten from one of those collection points, and then deliver it to the appropriate address.

One of the taxi suppliers has agreed to participate in this program. Others are likely to follow. Still others may decline.

Of course, some drivers may be allergic to cats, so those drivers should never be selected for this service. Also, some customers will undoubtedly have similar allergies, so a vehicle that has been used to deliver kittens within the last 3 days should not be selected for customers who declare such allergies.

Look at that diagram of services. How many of those services will have to change to implement this feature? All of them. Clearly, the development and deployment of the kitty feature will have to be very carefully coordinated.

In other words, the services are all coupled, and cannot be independently developed, deployed, and maintained.

This is the problem with cross-cutting concerns. Every software system must face this problem, whether service oriented or not. Functional decompositions, of the kind depicted in the service diagram in Figure 27.1, are very vulnerable to new features that cut across all those functional behaviors.

OBJECTS TO THE RESCUE

How would we have solved this problem in a component-based architecture? Careful consideration of the SOLID design principles would have prompted us to create a set of classes that could be polymorphically extended to handle new features.

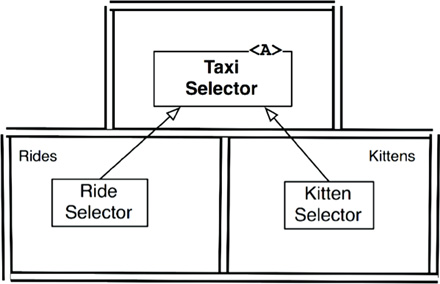

The diagram in Figure 27.2 shows the strategy. The classes in this diagram roughly correspond to the services shown in Figure 27.1. However, note the boundaries. Note also that the dependencies follow the Dependency Rule.

Much of the logic of the original services is preserved within the base classes of the object model. However, that portion of the logic that was specific to rides has been extracted into a Rides component. The new feature for kittens has been placed into a Kittens component. These two components override the abstract base classes in the original components using a pattern such as Template Method or Strategy.

Note again that the two new components, Rides and Kittens, follow the Dependency Rule. Note also that the classes that implement those features are created by factories under the control of the UI.

Clearly, in this scheme, when the Kitty feature is implemented, the TaxiUI must change. But nothing else needs to be changed. Rather, a new jar file, or Gem, or DLL is added to the system and dynamically loaded at runtime.

Thus the Kitty feature is decoupled, and independently developable and deployable.

COMPONENT-BASED SERVICES

The obvious question is: Can we do that for services? And the answer is, of course: Yes! Services do not need to be little monoliths. Services can, instead, be designed using the SOLID principles, and given a component structure so that new components can be added to them without changing the existing components within the service.

Think of a service in Java as a set of abstract classes in one or more jar files. Think of each new feature or feature extension as another jar file that contains classes that extend the abstract classes in the first jar files. Deploying a new feature then becomes not a matter of redeploying the services, but rather a matter of simply adding the new jar files to the load paths of those services. In other words, adding new features conforms to the Open-Closed Principle.

The service diagram in Figure 27.3 shows the structure. The services still exist as before, but each has its own internal component design, allowing new features to be added as new derivative classes. Those derivative classes live within their own components.

Figure 27.3 Each service has its own internal component design, enabling new features to be added as new derivative classes

CROSS-CUTTING CONCERNS

What we have learned is that architectural boundaries do not fall between services. Rather, those boundaries run through the services, dividing them into components.

To deal with the cross-cutting concerns that all significant systems face, services must be designed with internal component architectures that follow the Dependency Rule, as shown in the diagram in Figure 27.4. Those services do not define the architectural boundaries of the system; instead, the components within the services do.

Figure 27.4 Services must be designed with internal component architectures that follow the Dependency Rule

CONCLUSION

As useful as services are to the scalability and develop-ability of a system, they are not, in and of themselves, architecturally significant elements. The architecture of a system is defined by the boundaries drawn within that system, and by the dependencies that cross those boundaries. That architecture is not defined by the physical mechanisms by which elements communicate and execute.

A service might be a single component, completely surrounded by an architectural boundary. Alternatively, a service might be composed of several components separated by architectural boundaries. In rare2 cases, clients and services may be so coupled as to have no architectural significance whatever.

1. Therefore the number of micro-services will be roughly equal to the number of programmers.

2. We hope they are rare. Unfortunately, experience suggests otherwise.