Chapter 12

Subjects, networks, assemblages

A materialist approach to the production of social space

The old and assumed isomorphism between culture, polity, and territory is no longer to be taken as given. The fundamental principle upon which national cultures and communities have been predicated has been called into question.

(Kevin Robins, 2007, p. 158)

What is the territory of a human being? Where are the borders of the society or culture to which a given person belongs? If a society is a collective composed of subjects who share social, political, and economic relations, what are the boundaries around those relations? What is the radius of a citizen’s public sphere, and where do its edges bump up against other spheres of discourse and governance? At the outset of the twenty-first century, in the context of transnational migration and travel, neoimperial military and economic interdependencies, and planetwide technical networks of entertainment and surveillance, the notion of a discrete, coherent social space – “a society,” “a culture” – has become deeply problematic. The precise logics and ultimate consequences of globalization may remain unclear. However, as noted by Kevin Robins in the epigraph above, it is quite apparent that the ontological assumptions, theoretical frameworks, and methodological tools inherited from modern social theories that were predicated on the notion of a society are inadequate for conceptualizing the current state of affairs. Modern social theory took shape as national economies, governments, communication infrastructures, and cultures became more cohesive and reified; consequently, the mark of the nation is deeply inscribed on nineteenth- and twentieth-century thought. If the nation has been an imagined community not only for the masses (Anderson, 1991) but also for theorists – a container of thought not only for popular belief but also for theory – how do we now reconceptualize and investigate the new, more rhizomatic, contours of social space?

In the context of mobility and translocal connectivity, our aim must be to discover the contours of social space without presuming to know them in advance – to follow the flows that reveal the connections and relationships that are salient for a given subject. A materialist theory of communication provides a useful starting point for this task. If we understand communication not as the transmission of meaning but as the production of a common social territory in which geography, mobility, and economic relations play as much a role as the circulation of information and the sharing of language and cultural practices (Carey, 1989, 1997), it becomes apparent that our first question should be, who is connected to whom?

In this chapter, we develop a conceptual model of social space grounded in a materialist understanding of communication. We begin with the basic Marxist premise articulated by Henri Lefebvre (1974, 1991): that the production of space is the production of the social relations of production. Because the social relations of production (and reproduction) are often translocal and transnational, we draw on network theory to develop a conceptual framework for the analysis of social space as non-Euclidean (Appadurai, 1990) and rhizomatic (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987). In our view, the social space of a given subject is simultaneously expressed in and constituted by three kinds of interrelated networks: social networks, or networks of social relations, including relations of production and consumption (Adams,2005; Lefebvre,1991; Marx, 1972 [1849], 1904) and relations of family and friends (Hannerz, 1996; Morley, 2000; Rouse, 1995; Wellman, 2001), geographical networks, or networks of mobility and emplacement (Carrasco et al., 2008; Clifford, 1989, 1992; Larsen et al., 2006; Marcus, 1995; Massey, 1993; Sinclair and Cunningham, 2000), and technical networks, or networks of mediated communication (Castells, 1996, 2009; Fuller, 2005; Hansen, 2006; Morley and Robins, 1995; Sinclair and Cunningham, 2000). We understand a given subject’s practices or activities as an actualization of all three of these networks. Finally, we bring in the concept of agencement (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987) or assemblage (DeLanda, 2006; Marcus and Saka, 2006; Wise, 2005) to describe the consistency and effectivity of the molar arrangements that govern certain portions of a subject’s networks and activities. In closing, we offer some brief reflections on the methodological implications of defining social space in this way.

A materialist theory of social space begins with a focus on the social relations of production (Marx, 1972 [1849]), the means by which human beings transform nature and reproduce their survival as a species, which they do collectively and in particular spatial arrangements, like other social animals such as ants. From this standpoint, communication is, most fundamentally, a spatiotemporal process of arrangement – of bodies, brains, and materials – for the production and reproduction of life, an agencement (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987) or assembling that composes relations for specific purposes. Within the Marxist tradition, the key theorist of social space is Henri Lefebvre (1991). For Lefebvre, the production of space is, most fundamentally, a spatial organization of the social relations of production – a matter of organizing infrastructure, capital, the built environment, and people spatially for the reproduction of capitalism.1 Yet Lefebvre, like many other modern theorists of society and culture, sought to address the production of space “in a given society” (Lefebvre, 1991, pp. 33, 182, 215). We must now ask how space is produced when capitalism is increasingly globalized, networked, and information-driven … when nations, regions, and cities are increasingly reorganized in relation to a globalizing logic of network power (Castells, 2009) and empire (Hardt and Negri, 2000). How is social space conceived, practiced, and lived (Lefebvre, 1991) now that people are understood not only as inhabiting globalized cities (Massey, 1993; Sassen, 2000a, 2000b, 2007) and rhizomatic media ecologies (Fuller, 2005; Hansen, 2006) but are also recognized as mobile (Sheller and Urry, 2006) and connected to distant others (Adams, 2005; Giddens, 1991; Morley, 2000) – when their relation to any specific place, nation, city, or cultural field has become unpredictable?

The increasing complexity of social relations, mobility, and mediated connectivity in late modernity requires a new approach to the study of social space – one which does not start with a sweeping, metahistorical narrative about the transformation of place and space (Castells, 1996) but begins, instead, with what is happening on the ground: with empirical fieldwork that will allow us to discover the realities of spatial transformation that people are (or may be) actually experiencing (Murphy, 2005; Murphy and Kraidy, 2003, 2006; Sassen, 2007). The point is not that the nation, the city, or other archetypal modern forms of spatial organization are obsolete (Waisbord and Morris, 2001), but rather that we simply do not know, for lack of empirical research, how logics of capital, logics of nationality, logics of government and security, and other logics of spatial organization come together to constitute places and to shape the practices and lived experience of space for a specific person or community. Because people are mobile, involved in distanciated social relations, and connected to translocal networks of media and information, they may be articulated to any number of constellations of social relations, to multiple modes of production, and to diverse representations of space operating on a range of scales. We can no longer be certain that their momentary, immediate geographical surroundings define their place. Instead, we need to discover how subjects are linked, via their practices, to particular places and patterns of mobility, to specific technical media and fields of discourse, and to certain networks of other people … and we need to discover how they experience place, space, and mobility as an expression of those connections.

But how do we discover which places, relations, networks, and meanings are salient for a particular individual or collective subject? To answer that question, we propose an analytical strategy based on three premises: methodological individualism, a “hydrological” strategy for the analysis of flows, and the concept of agencement (arrangement or assemblage). We begin with particular subjects, their spatial practices, and their spatial representations – not as discrete, autonomous monads but as concrete lives (Deleuze, 2005; Ferrarotti, 2007; Sotirin, 2010) unfolding at the intersection of conceived, perceived, and lived space (Lefebvre, 1991). We then work inductively, “following the flows” back upstream (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p. 454) to discover the salient arrangements or assemblages (DeLanda, 2006; Deleuze and Guattari, 1987; Wise, 2005) to which that subject is linked. As an alternative to Euclidean assumptions about the location of power, culture, capitalist production, and subjectivity within coherent, coterminous territorial containers (Appadurai, 1990), a hydrological approach in combination with assemblage theory allows us to identify the forces operating in the milieu of a subject without assuming that geographical or cultural proximity determines relevance. Our aim is not simply to rethink place, but rather to discover the social space of an individual – a social space composed of networks of social relations, mobilities and emplacements, and selective appropriations of all kinds of discursive materials.

Subjects, activities, networks, and assemblages: a conceptual model of social space2

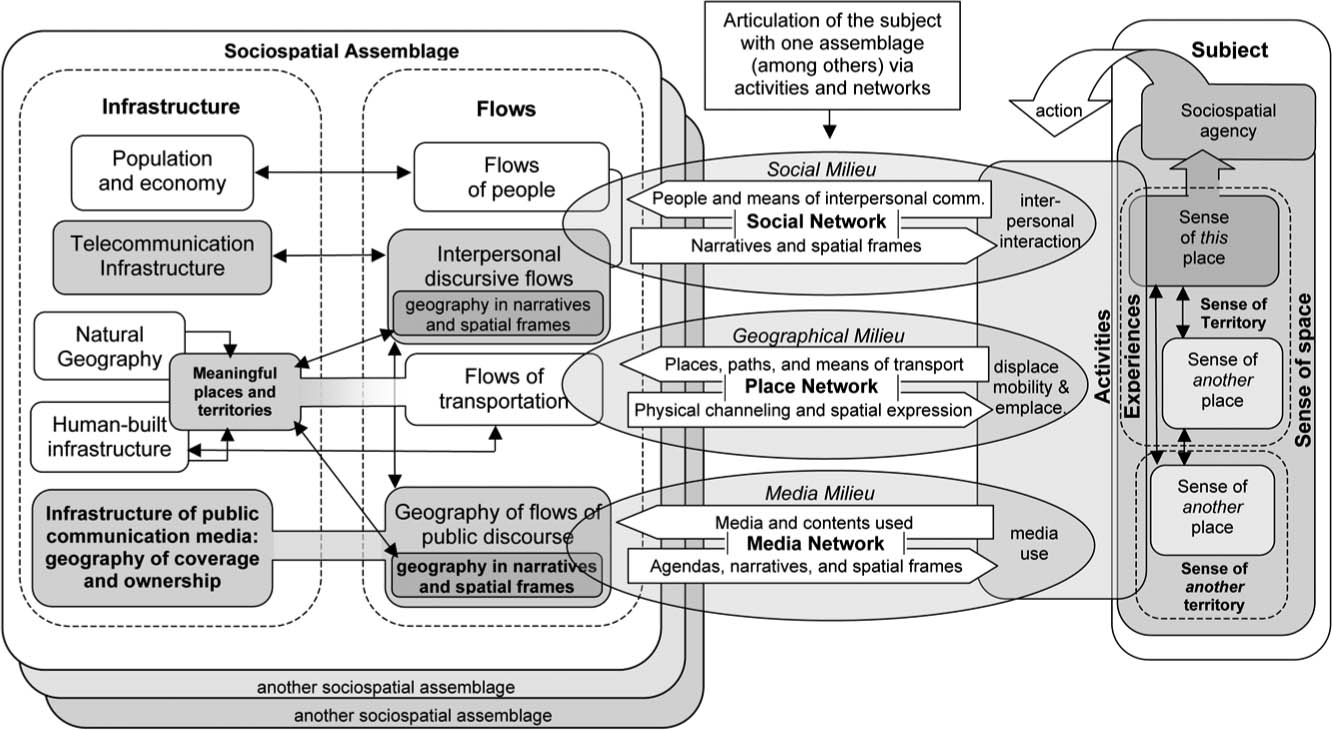

The model we are employing to define and analyze social space draws on four basic concepts: assemblages, networks, activities, and subjects (see Figure 12.1). Assemblages link subjects (whether individual or collective), via networks and activities, to particular arrangements of bodies, technologies, and materials in order to do something – to enable the production of surplus value, to produce citizens, to move or secure populations or resources, to expand human knowledge and develop technologies, to manage and direct force and violence, to create community and solidarity, and so on. Networks (in the center of the model) are the virtual links – that is, the potential articulations, or ties – that connect subjects to assemblages. We focus on social networks, geographical networks, and networks of technical media.

Figure 12.1 Conceptual model of social space.

Much has been written about networks, but here we are proposing to reimagine networking as assembling, an argument which will be developed below. Activities – the things we do everyday, alone and with others – are actualizations of networks; that is, they actualize the virtual links of one’s networks by expressing virtual (potential) relations in actual activity.3 Finally, subjects are human individuals or collectives that perceive, experience, and define reality from a particular perspective and position within relations of power (Foucault, 1982).

We are specifically interested in the ways in which subjectivity entails lived experiences of space and place, which in turn enables spatial practices (Lefebvre, 1991, p. 38). As indicated in the model (on the right-hand side, within the box labeled subject), we break down lived experience of space into sense of place, sense of territory, and sense of space (see below). Finally, our model includes sociospatial agency: subjects are subjects of their activities as well as being subjected to the effects of power (Foucault, 1982, p. 781). We now develop each of these elements of the model – assemblages, networks, activities, subjects, and agency – in greater detail.

The first element of the model (on the far left of the diagram in Figure 12.1) is the assemblage, or more precisely, a constellation of multiple assemblages to which a given subject is articulated. Assemblages, in this model, are the bundles of arrangements and logics that shape a subject’s emplacement, mobility, and connectivity – that is, their social space – with the aim of producing a specific effect. Assemblages are compositions of heterogeneous elements “deducted from the flows” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p. 448) and made to function according to a certain set of logics. As these elements are brought into relations of composition with one another, they constitute a specific territory for a certain duration and code the component elements, and the assemblage as a whole, according to specific discursive categories and rules (DeLanda, 2006; Deleuze and Guattari, 1987; see also, Wiley, 2005; Wise, 2005). As an initial approximation, assemblages may be thought of as similar to organizations or systems (DeLanda, 2006). However, in opposition to the reification and functionalism that often characterizes systems theory and organizational theory (and, at times, DeLanda’s own analysis), the concept of assemblage emphasizes the heterogeneity of the incorporated elements; the incompleteness of their functional integration; the constitutive force of the relations of content/expression that hold the elements together; and the dynamic, unfolding quality of the elements, and of the assemblage as a whole. If we retain the connotations of the original French word employed by Deleuze and Guattari, agencement, it is clear that an assemblage is better thought of as an arrangement or an assembling, and more specifically as an assembling for – that is, as a mustering or gathering together of elements – people, materials, activities, and signs – with specific capacities and in the service of particular logics or aims (Wiley, 2005; Wise, 2005). Assemblage theory gives us a way of thinking about what is connected to what, and about what matters in a given context, without assuming a Euclidean, Westphalian geography of stable, coherent containers with coterminous borders (Appadurai, 1990), and without assuming that geographical proximity determines social, economic, or cultural salience.

Three additional points about the application of assemblage theory must be clarified before we move on. First, assemblages do not necessarily correspond to traditional social, cultural, and political entities, which are generally imagined to be contained within, and coterminous with, coherent geographical territories. DeLanda (2006) analyzes nations as examples of assemblages, for example, but it would be more accurate to include, as part of a nation assemblage, any elements anywhere that are subjected to that specific logic of nationality. Following this approach, there is an USassemblage that is not limited to the official borders of the United States. It incorporates all the places, practices, and people, wherever they may be, who are governed by a logic of US Americanness (however we might specify that logic). This would include not only employees of the US government and military stationed around the world but also entire cultural enclaves surrounding military bases, expatriate communities, Sheraton hotels, and tourist circuits more broadly, as well as the many sites in which other non-US citizens are drawn into, or subjected to, logics of Americanization via military action, corporate ownership, language, media use, subcultures of personal style, economic relations, political discourse, and so on. The topology of an assemblage, then, is not defined by official borders or common-sense assumptions, but rather by following the flows to find all the places in which the logics of the assemblage are operating.

Second, it must be emphasized that subjects are caught up, simultaneously, in multiple assemblages. A person, for example, may be simultaneously a family member, a laborer, a national citizen, a fan of a global rock band, and a follower of a religion; each one of these subject positions may be linked to a specific assemblage, or a single assemblage may place the person in multiple subject positions simultaneously: the church-sponsored Christian rock concert captures a family and positions the man simultaneously as a father, a fan, and a believer. In other words, the goal of analysis is not to identify the one assemblage “in which” a subject is located (e.g., a nationstate assemblage or a city as assemblage), but rather to discover the entire constellation of assemblages that exert force in that subject’s life, linking him or her into multiple – sometimes contradictory, sometimes resonant – roles and relations. It is this constellation of assemblages and the ways in which they position a subject that explains the complex, changing, and apparently idiosyncratic patterns of mobility, emplacement, social interaction, and communication that characterize a life.

Third, we must point out that assemblages themselves are dynamic, mobile, and temporal; the apparent stasis and durability of some macroassemblages such as institutions or cities is a product of our human-centered temporal perspective, which is characterized by relatively short-term existence and relatively high mobility. From a longer-term perspective, however, even apparently durable assemblages such as empires, cities, and political regimes appear ephemeral: empires fall; centers of business and residence that thrived in earlier times are now ghost towns; regions ruled by military regimes in the past are now governed by civilian leaders while democratic regimes in other areas are subjected increasingly to logics of security, surveillance, and control. In our analysis of social space, we must take care to avoid reifying existing states of affairs and assuming that existing centers of power, territories, and relations will necessarily endure or maintain their present-day configuration. A key advantage of assemblage theory is that it allows us to discover emerging networks, embryonic relations of power, and evolving territories – precisely the forms of social organization that we suspect may accompany increased mobility and connectivity.

Assemblages, milieus, and networks

Assemblages are constituted via territorialization and coding of milieus (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987), a process that draws from the surrounding world (the milieu) to produce specific linkages and relations according to specific logics. These connections articulate, or link, the subject to the assemblage, a process that leads to what have popularly been called networks (Castells, 2009; Wellman, 2001). In fact, we propose to reinterpret “networks” from the standpoint of assemblage theory. Networks (or networking) can be understood as the work of tying subjects into social relations – the process of linking or articulating subjects into assemblages. More precisely, networks can be thought of as sets of virtual articulations – potential linkages – which are actualized through activities or practices Deleuze (1994). In this conceptual model, we pay attention to three kinds of networks that we see as critical for linking subjects to assemblages: social networks, networks of technical media, and geographical networks.

Social networks

Within social milieus – the populations through which we move and with which we are potentially connected – we enter into, or are caught within, social interactions whose virtual dimensions are social relations and social networks.

Within technological milieus – the infrastructures, technologies, and media that surround us – our attention is captured and focused on specific sources and discourses whose virtual elements are networks of technical media.

Geographical networks

Within geographical milieus – the built and natural environments through which we move, including the available infrastructures and technologies of mobility, we enact specific practices of mobility and emplacement; the virtual element of these spatial practices are geographical networks, or networks of mobility and emplacement.

In each of these cases, we distinguish between milieus, actual practices, and virtual networks. Milieus are the surroundings from which specific elements are selected (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p. 245) Practices are activities (including physical actions as well as statements and other incorporeal acts) that actualize our various networks. Networks are the virtual, or potential, elements and relations that make up our social space – geographies, people, and media that we perceive, remember, imagine, or desire. These types of network are not expressions of individual freedom and choice but are rather the modes by which a subject is linked to assemblages. In other words, we are not autonomous architects of our social, communicational, and geographical networks; we are born into nets that were already working on us before we came along.

All three of these networks and modes of articulation are actualized, or expressed, in a person’s practices or activities. Any specific activity that a subject undertakes is the product of the multiple articulations that link that subject simultaneously into a whole constellation of assemblages acting in that subject’s milieu. Furthermore, activities themselves depend on the salience and power of one assemblage’s shift in time and space in relation to others. For example, as one moves through one’s daily activities, one experiences the shifting, overlapping salience of the family assemblage and the work assemblage.

The subject

Finally, the model focuses attention on several specific elements of subjectivity that are relevant for conceptualizing a subject’s lived experience of space: sense of place, sense of territory, and sense of space. We define sense of place as the set of meanings, affects, and expectations that a subject associates with a place, including an understanding of the characteristics of the people, activities, and physical components “appropriate” to the place. Sense of place is fundamentally relational, so that my experience of this place is defined in relation to other places, whose positive or negative differences make this place distinctive and meaningful (this is my house, not yours; this is my country, not theirs). Out of our knowledge and experience of multiple places, we develop a sense of territory – a space imagined and experienced as the container of past, current, and potential future activities, within which a subject locates his own places and/or the places of others. Like sense of place, sense of territory can be socially constructed on any scale, but a territory is always understood in relation to a set of places, as the container of those places. Finally, sense of space is the overall set of relational meanings, affects, and expectations within which a subject understands and experiences all the places and territories she knows (whether these have been experienced corporeally, through embodied practices, or incorporeally, via place images and narratives circulated in the media and the accounts of others). Our sense of space positions us, cognitively and affectively, in relation to the places and territories we know (our own and others’), the practices of mobility and stopping that structure our everyday life, and the associated activities and social relations that we experience in places and in movement. It is perhaps not so different from what sociologists once called a “worldview,” or what Raymond Williams famously called “a whole way of life.”

Conclusions: biographical starting points and a hydrological method

The methodological challenges entailed in applying this model to research on social space and sense of place are substantial. The extent and complexity of present-day transportation networks, social networks, and media networks, as well as the extensive and increasingly accelerated flows of populations, materials, and media content they facilitate, create significant challenges for research on actual configurations of social space. In order to discover what constellations of assemblages are at work constituting a subject’s social space (rather than presuming to know this in advance based on a person’s present geographical location, their birthplace, or their citizenship), we employ a strategy of methodological individualism,4 which involves working inductively, from empirical research (right to left in our model) – from the subject and her activities to the networks, and finally to the assemblages. By methodological individualism, we mean that we must begin with a person – or perhaps more accurately, “a life” (Deleuze, 2005; Sotirin, 2010) – and follow the flows and connections that articulate him or her to all the assemblages to which he or she is linked. In this way, we can apply Deleuze and Guattari’s call for a nomad science: a “hydraulic” (or, as we prefer, hydrological) approach to research (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p. 397, 454) in which one follows the flows outward (or inward) from a given starting point to discover the distant connections and the geographical, social, or cultural reach of the assemblages that are acting in the milieu of the subject.

A key point in our argument is that methodological individualism is necessary because, in the context of mobility and global connectedness, no two subjects are linked to the same set of assemblages, or linked in the same way. Because individuals are mobile, because they may inhabit distinct media and information ecologies, and because their social relations and networks may be translocal, it cannot be assumed that two people inhabiting (or working in, or passing through) a given urban area or national territory are members of a common society or that they share a common sense of place. Each person – each subject, in our model – practices and experiences space differently and, most significantly, may be articulated to different conceived spaces (Lefebvre, 1991) – that is to different dominant assemblages that compose social relations and produce space. For example, a university professor may belong to the same neighborhood and even to the same work assemblage as a university maintenance employee, but the professor is articulated to a translocal assemblage of academic knowledge production whose key sites of social interaction and information exchange are distributed across the globe. Methodological individualism allows us to follow those linkages and uncover the distant (or not so distant) assemblages shaping the social space of our interviewees.

Franco Ferrarotti’s (2007) life history sociology provides us with an excellent theoretical rationale for this focus on the individual. Following Ferrarotti, we see individual lives as syntheses of the social and as lenses through which the social world can be understood in all its complexity. As Ferrarotti puts it, “our social system is completely within each of our actions, our dreams, fantasies, accomplishments, and behavior, and the history of this system is completely within the history of our individual life” (ibid., p. 239). The individual biography is not seen as a representative (or unrepresentative) example of the social, but rather as a prism which refracts the social field in all its complexity, from a specific standpoint within the social field. Furthermore, the individual life is not determined by the social in a classical sociological sense but rather expresses the lived complexity and active appropriation of the social by the individual (ibid., p. 239).

It is the implication, or infolding, of the social in the individual that interests us. We intend for our analysis to work through individual accounts to illuminate the social – to work from the practices and experiences of individual subjects toward the articulations, networks, and assemblages that compose the rhizomatic social spaces of an increasingly globalized world. Much remains to be worked out, theoretically and methodologically, in this materialist model of social space. We hope that the initial conceptual elements proposed here provide a useful scaffold for future work.

Notes

1 Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space is of course far more complex than this. However, in a lecture published in 1974, Lefebvre asserted, in an uncharacteristically straightforward manner, “It is in space, and through space, that the reproduction of the social relations of capitalist production are carried out” (1974, p. 223). For a more nuanced discussion of Lefebvre and social space, see Hay (2001, 2011).

2 For an initial development of this proposal, see Wiley et al. (2010).

3 We are employing the terms “virtual” and “actual” in a Deleuzian sense (Deleuze, 1994, pp. 183, 206–215).

4 Methodological individualism, it must be said right away, is not the same as an ontological commitment to the autonomy or individuality of subjects.

References

Adams, P. C. 2005. The boundless self: Communication in physical and virtual spaces. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Anderson, B. 1991. Imagined communities (Rev. ed.). London: Verso.

Appadurai, A. 1990. Disjuncture and difference in the global cultural economy. Public Culture 2(2): 1–24.

Carrasco, J. A., Miller, E. J., and Wellman, B. 2008. How far and with whom do people socialize?: Empirical evidence about distance between social network members. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2076: 114–122.

Carey, J. W. 1989. Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society. Boston: Unwin Hyman.

Carey, J. W. 1997. Afterword: The culture in question, in E. S. Munson, & C. Warren (eds.), James Carey: A critical reader (pp.308–339). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Castells, M. 1996. The space of flows, in M. Castells (ed.), The information age: Economy, society and culture. Volume I: Rise of the network society (Chapter 6, pp. 376–428). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Castells, M. 2009. Communication power. London: Oxford University Press.

Clifford, J. 1989. Notes on Travel and Theory, in J. Clifford and V. Dhareshwar (eds.), Traveling theories, traveling theorists (Special issue of the journal Inscription). New York: Routledge.

Clifford, James. 1992. Traveling Cultures, in L. Grossberg, C. Nelson and P. Treichler (eds.), Cultural studies. New York: Routledge.

DeLanda, Manuel. 2006. A new philosophy of society: assemblage theory and social complexity. London and New York: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1994. Difference and repetition. Translated by Paul Patton. London and New York: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Deleuze, Gilles. 2005. Pure immanence: Essays on a life. Cambridge, MA: Zone Books.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Guattari, F. 1987. A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Ferrarotti, F. 2007. Biography and the Social Sciences, in D. McCarthy (ed.), Social theory for old and new modernities: Essays on society and culture, 1976–2005, pp. 233–248. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Foucault, M. 1982. The subject and power. Critical Inquiry 8(4): 777–795.

Fuller, Matthew. 2005. Media ecologies: Materialist energies in art and technology. Boston: MIT Press.

Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hannerz, U. 1996. Transnational connections: Culture, people, places. London: Routledge.

Hansen, M. B. N. 2006. Bodies in code: Interfaces with digital media. London: Routledge.

Hardt, Michael, and Negri, Antonio. 2000. Empire. Cambridge, MA, and London, England: Harvard University Press.

Hay, J. 2001. Locating the televisual. Television New Media 2(3): 205–234.

Hay, J. (2011). The Birth of the “Neoliberal” City and Its Media, in Packer, J., and Wiley, S. B. C. (eds.), Communication Matters: Materialist Approaches to Media, Mobility and Networks (Chapter 8). Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

Larsen, Jonas, Axhausen, Kay W., and Urry, John. 2006. Geographies of social networks: Meetings, travel and communications. Mobilities 1(2): 261–283.

Lefebvre, H. 1974. La produccion del espacio. Papers: Revista de Sociologia. No. 3. Available: http://www.raco.cat/index.php/Papers/article/view/52729

Lefebvre, H. 1991. The production of space. Malden, MA, USA; Oxford, UK; Victoria, Australia: Blackwell.

Marcus, George E. 1995. Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology 24: 95–117.

Marcus, G. E., and Saka, E. 2006. Assemblage. Theory Culture Society 23(2–3): 101–109.

Marx, K. 1978 [1849]. Wage labour and capital, in Marx, K., and Engels, F. (eds.), The Marx-Engels Reader (Second Ed. Trans. R. C. Tucker). New York: W. W. Norton.

Massey, Doreen. 1993. Power-Geometry and a Progressive Sense of Place, in B. John, (eds.), Mapping the futures: Local cultures, global change (Chapter 4, pp. 59–69). London: Routledge.

Morley, D. 2000. Home territories: Media, mobility and identity. London: Routledge.

Morley, D., and Robins, K. 1995. Spaces of identity: Global media, electronic landscapes, and cultural boundaries. London: Routledge.

Murphy, P. 2005. Fielding the study of reception: Notes on “negotiation” for global media studies. Popular Communication.

Murphy, P. and Kraidy, M. 2003. Global media studies: Ethnographic perspectives. London: Routledge.

Murphy, P. and Kraidy, M. 2006. International communication, ethnography, and the challenge of globalization. Communication Theory.

Robins, Kevin. 2007. Transnational cultural policy and European cosmopolitanism. Cultural Politics 3(2): 147–174.

Rouse, R. 1995. Questions of identity: Personhood and collectivity in transnational migration to the United States. Critique of Anthropology 15(4): 351–380.

Sassen, Saskia. 2000a. Spatialities and temporalities of the global: Elements for a theorization. Public Culture 12(1): 215–232.

Sassen, Saskia. 2000b. The global city. rev. ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sassen, S. 2007. The Places and Spaces of the Global: An Expanded Analytic Terrain, in D. Held and A.G. McGrew (eds.), Globalization Theory: Approaches and Controversies. Cambridge, UK: Polity. pp. 79–105.

Sheller, M., and Urry, John. 2006. The new mobilities paradigm. Environment and Planning A 38: 207–226.

Sinclair, John, and Cunningham, Stuart. 2000. Go with the flow: Diasporas and the media. Television & New Media 1: 11–31.

Sotirin, P. 2010. Autoethnographic mother-writing: Advocating radical specificity. Journal of Research Practice 6(1), Retrieved April 25, 2011, from http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/220/189

Waisbord, S., and Morris, N. 2001. Introduction: Rethinking Media Globalization and State Power. in S. Waisbord and N. Morris (eds.), Media and Globalization: Why the State Matters, pp. vii–xvi. Lanham, MD; Boulder, CO; New York and Oxford, UK: Rowman and Littlefield.

Wellman, Barry. 2001. The persistence and transformation of community: From neighbourhood groups to social networks. Report to the Law Commission of Canada. Toronto, Canada: Wellman Associates.

Wiley, S. B. C. 2004. Rethinking nationality in the context of globalization. Communication Theory 14: 78–96.

Wiley, S. B. C. 2005. Spatial materialism: Grossberg’s Deleuzean cultural studies. Cultural Studies 19: 63–99.

Wiley, S. B. C. 2006a. Transnation: Globalization and the reorganization of Chilean television in the early 1990s. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 50(3): 400–420.

Wiley, S. B. C. 2006b. Assembled agency: Media and hegemony in the Chilean transition to civilian rule. Media, Culture & Society 28(5): 671–693.

Wiley, S. B. C., Sutko, D. M., and Moreno, T. 2010. Assembling social space. The Communication Review 13: 1–37.

Wise, J. Macgregor. 2005. Assemblage, in C. Stivale (ed.), Gilles Deleuze: Key concepts, pp. 77–87. Montreal and Kingston, Canada: McGill-Queen’s Press.