2

![]()

WHAT MAKES AN ANALYTICAL

COMPETITOR?

Defining the Common

Key Attributes of Such Companies

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO compete on analytics? We define an analytical competitor as an organization that uses analytics extensively and systematically to outthink and outexecute the competition. In this chapter, we’ll describe the key attributes of companies that compete on analytics, and describe the levels and stages of these attributes that we found in researching actual organizations.

Among the firms we studied, we found that the most analytically sophisticated and successful had four common key characteristics: (1) analytics supported a strategic, distinctive capability; (2) the approach to and management of analytics was enterprise-wide; (3) senior management was committed to the use of analytics; and (4) the company made a significant strategic bet on analytics-based competition. We found each of these attributes present in the companies that were most aggressively pursuing analytical approaches to business.

We don’t know, of course, exactly how many analytical competitors there are, but we do have data allowing a good estimate. In a global survey of 371 medium to large firms conducted in late 2005, we asked respondents (IT executives or business executives familiar with their companies’ enterprise IT applications) how much analytical capability their organizations had. The highest category was described by the statement “Analytical capability is a key element of strategy” for the business. Ten percent of the respondents selected that category. According to our detailed analysis of the data, perhaps half of these firms are full-bore analytical competitors. There may be slightly more or fewer, but we don’t know of any better estimate.

Primary Attributes of Analytical Competitors

Next, we’ll describe how several of the companies we studied exemplify the four attributes of analytical competition. True analytical competitors exhibit all four; less advanced organizations may have only one or two at best.

Support of a Strategic, Distinctive Capability

It stands to reason that if analytics are to support competitive strategy, they must be in support of an important and distinctive capability. As we mentioned in the first chapter, the capability varies by organization and industry, and might involve supply chains, pricing and revenue management, customer service, customer loyalty, or human resource management. At Netflix, of course, the primary focus for analytics is on predicting customer movie preferences. At Harrah’s, it’s on customer loyalty and service. Marriott International’s primary analytical orientation is on revenue management. Wal-Mart obviously emphasizes supply chain analytics. Professional sports teams generally focus on human resources, or choosing the right players.

Having a distinctive capability means that the organization views this aspect of its business as what sets it apart from competitors and as what makes it successful in the marketplace. In companies without this strategic focus, analytical capabilities are just a utility to be applied to a variety of business problems without regard for their significance.

Of course, not all businesses have a distinctive capability. They usually suffer when they don’t. It’s not obvious, for example, what Kmart’s, US Airways’, or General Motors’ distinctive capabilities are. To the outside observer, they don’t do anything substantially better than their competitors—and their customers and potential shareholders have noticed. Without a distinctive capability, you can’t be an analytical competitor, because there is no clear process or activity for analytics to support.

It’s also possible that the distinctive capability an organization chooses would not be well supported by analytics—at least this has been true in the past. If the strategic decisions an organization makes are intuitive or experience based and cannot be made analytically, it wouldn’t make sense to try to compete on statistics and fact-based decisions. We mentioned the fashion and executive search businesses in this regard in chapter 1. One might add management consulting to this list, in that most consulting advice is based on experience rather than analytics. We suspect, however, that in each of these industries there is the potential for analytical competition and that some firm will adopt it at some point in time. Fashion businesses could try to decompose and predict the elements of consumer taste. Executive search firms could build their businesses around a database of what kinds of executives perform well under certain circumstances. And consultants (and lawyers and investment bankers, for that matter) could base their advice to clients on detailed statistical analysis of what management approaches have been effective in specified business situations. They could perhaps transform their industries by taking an analytical approach to strategy.

A corollary of this factor is that analytical competitors pay careful attention to measures of the distinctive capabilities in their businesses. They engage in both exploitation and exploration of measures—they exploit existing measures to a considerable degree and are early to explore new measures. We’ve already discussed professional baseball, where teams like Oakland’s have moved to new measures of player performance. Consumer finance is another industry with a strong emphasis on developing new metrics.

Because there are many quantitative transactions in consumer financial services, it’s relatively easy to employ measures in decision making. Perhaps the most commonly used measure in consumer finance is the credit or FICO score, which is an indicator of the customer’s credit-worthiness. There are many possible credit scores, but only one official FICO score. (FICO scores are based on an algorithm developed by Fair, Isaac and Company [currently Fair Isaac Corporation] in 1989. Now, the three major credit bureaus have created a competitor, the Vantage Score, that, unlike the FICO score, is consistent with all credit ratings; in Europe, some financial services firms employ credit scores from Scorex.) Virtually every consumer finance firm in the United States uses the FICO score to make consumer credit decisions and to decide what interest rate to charge. Analytical banking competitors such as Capital One, however, adopted it earlier and more aggressively than other firms. Their distinctive capability was finding out which customers were most desirable in terms of paying considerable interest without defaulting on their loans. After FICO scores had become pervasive in banking, they began to spread to the insurance industry. Again, highly analytical firms such as Progressive determined that consumers with high FICO scores not only were more likely to pay back loans, but also were less likely to have automobile accidents. Therefore, they began to charge lower premiums for customers with higher FICO scores.

Today, however, there is little distinction in simply using a FICO score in banking or property and casualty insurance. The new frontiers are in applying credit scores in other industries and in mining data about them to refine decision making. Some analysts are predicting, for example, that credit scores will soon be applied in making life and health insurance decisions and pricing of premiums. At least one health insurance company is exploring whether the use of credit scores might make it possible to avoid requiring an expensive physical examination before issuing a health policy. One professor also notes that they might be used for employment screening:

It is uncommon to counsel individuals with financial problems who don’t have other kinds of problems. You’re more likely to miss days at work, be less productive on the job, as well as have marriage and other relationship problems if you are struggling financially. It makes sense that if you have a low credit score that you are more likely to have problems in other areas of life. Employers looking to screen a large number of applicants could easily see a credit score as an effective way to narrow the field.1

Since credit scores are pervasive, some firms are beginning to try to disaggregate credit scores and determine which factors are most closely associated with the desired outcome. Progressive Insurance and Capital One, for example, are both reputed to be disaggregating and analyzing credit scores to determine which customers with relatively low scores might be better risks than their overall scores would predict.

One last point on the issue of distinctive capabilities. These mission-critical capabilities should be the organization’s primary analytical target. Yet we’ve noticed that over time, analytical competitors tend to move into a variety of analytical domains. Marriott started its analytical work in the critical area of revenue management but later moved into loyalty program analysis and Web metrics analysis. At Netflix, the most strategic application may be predicting customer movie preferences, but the company also employs testing and detailed analysis in its supply chain and its advertising. Harrah’s started in loyalty and service but also does detailed analyses of its slot machine pricing and placement, the design of its Web site, and many other issues in its business. Wal-Mart, Progressive Insurance, and the hospital supply distributor Owens & Minor are all examples of firms that started with an internal analytical focus but have broadened it externally—to suppliers in the case of Wal-Mart and to customers for the other two firms. Analytical competitors need a primary focus for their analytical activity, but once an analytical, test-and-learn culture has been created, it’s impossible to stop it from spreading.

An Enterprise-Level Approach to and Management of Analytics

Companies and organizations that compete analytically don’t entrust analytical activities just to one group within the company or to a collection of disparate employees across the organization. They manage analytics as an organization or enterprise and ensure that no process or business unit is optimized at the expense of another unless it is strategically important to do so. At Harrah’s, for example, when Gary Loveman began the company’s move into analytical competition, he had all the company’s casino property heads report to him, and ensured that they implemented the company’s marketing and customer service programs in the same way. Before this, each property had been a “fiefdom,” managed by “feudal lords with occasional interruptions from the king or queen who passed through town.”2 This made it virtually impossible for Harrah’s to implement marketing and loyalty initiatives encouraging cross-market play.

Enterprise-level management also means ensuring that the data and analyses are made available broadly throughout the organization and that the proper care is taken to manage data and analyses efficiently and effectively. If decisions that drive the company’s success are made on overly narrow data, incorrect data, or faulty analysis, the consequences could be severe. Therefore, analytical competitors make the management of analytics and the data on which they are based an organization-wide activity. For example, one of the reasons that RBC Financial Group (the best-known unit of which is Royal Bank of Canada) has been a successful analytical competitor is that it decided early on (in the 1970s) that all customer data would be owned by the enterprise and held in a central customer information file. Bank of America attributes its analytical capabilities around asset and interest-rate risk exposure to the fact that risk was managed in a consistent way across the enterprise. Many other banks have been limited in their ability to assess the overall profitability or loyalty of customers because different divisions or product groups have different and incompatible ways to define and record customer data.

An enterprise approach is a departure from the past for many organizations. Analytics have largely been either an individual or a departmental activity in the past and largely remain so today in companies that don’t compete on analytics. For example, in a 2005 survey of 220 organizations’ approaches to the management of business intelligence (which, remember, also includes some nonanalytical activities, such as reporting), only 45 percent said that their use of business intelligence was either “organizational” or “global,” with 53 percent responding “in my department,” “departmental,” “regional,” or “individual.” In the same survey, only 22 percent of firms reported a formal needs assessment process across the enterprise; 29 percent did no needs assessment at all; and 43 percent assessed business intelligence needs at the divisional or departmental level.3 The reasons for this decentralization are easy to understand. A particular quantitatively focused department, such as quality, marketing, or pricing, may have used analytics in going about its work, without affecting the overall strategy or management approach of the enterprise. Perhaps its activities should have been elevated into a strategic resource, with broader access and greater management attention. Most frequently, however, these departmental analytical applications remained in the background.

Another possibility is that analytics might have been left entirely up to individuals within those departments. In such cases, analytics took place primarily on individual spreadsheets. While it’s great for individual employees to use data and analysis to support their decisions, individually created and managed spreadsheets are not the best way to manage analytics for an enterprise. For one thing, they can contain errors. Research by one academic suggests that between 20 percent and 40 percent of user-created spreadsheets contain errors; the more spreadsheets, the more errors.4 While there are no estimates of the frequency of errors for enterprise-level analytics, they could at least involve processes to control and eliminate errors that would be difficult to impose at the individual level.

A second problem with individual analytics is that they create “multiple versions of the truth,” while most organizations seek only one. If, for example, there are multiple databases and calculations of the lifetime value of a company’s customers across different individuals and departments, it will be difficult to focus the entire organization’s attention on its best customers. If there are different versions of financial analytics across an organization, the consequences could be dire indeed—for example, extending to jail for senior executives under Sarbanes-Oxley legislation. Hence there are considerable advantages to managing key data and analytics at the enterprise level, so that there is only one version of critical business information and analytical results for decision making. Then, of course, the information and results can be distributed widely for use across the organization. Harrah’s, for example, calls its management approach for customer analytics “centrally driven, broadly distributed.”

Enterprise management may take a variety of forms. For some organizations, it may mean only that central IT groups manage the data and procure and install the needed business intelligence software. For others, it may mean that a central analytical services group assists executives with analysis and decision making. As we’ll discuss in chapter 7, a number of firms have established such groups.

From an IT standpoint, another approach to enterprise-level management of analytics is the establishment of a business intelligence competency center, or BICC. According to SAS, a BICC is defined as “a cross-functional team with a permanent, formal organizational structure. It is owned and staffed by the [company] and has defined tasks, roles, responsibilities and processes for supporting and promoting the effective use of business intelligence across the organization.”5

In the business intelligence survey of 220 firms described earlier, 23 percent of respondents said their firm already had a BICC. The purpose of such groups is often limited to IT-related issues. However, it could easily be extended to include development and refinement of analytical approaches and tools. For example, at Schneider National, a large trucking and logistics company, the central analytical group (called engineering and research) is a part of the chief information officer organization, and addresses BICC-type functions as well as working with internal and external customers on analytical applications and problems.

Senior Management Commitment

The adoption of a broad analytical approach to business requires changes in culture, process, behavior, and skills for multiple employees. Such changes don’t happen by accident; they must be led by senior executives with a passion for analytics and fact-based decision making. Ideally, the primary advocate should be the CEO, and indeed we found several chief executives who were driving the shift to analytics at their firms. These included Gary Loveman, CEO of Harrah’s; Jeff Bezos, the founder and CEO of Amazon.com; Rich Fairbank, the founder and CEO of Capital One; Reed Hastings of Netflix; and Barry Beracha, formerly CEO of Sara Lee Bakery Group. Each of these executives has stated both internally and publicly that their companies are engaged in some form of analytical competition. For example, Fairbank commented, “It’s all about collecting information on 200 million people you’d never meet, and on the basis of that information, making a series of very critical long-term decisions about lending them money and hoping they would pay you back.”6

Fairbank summarizes this approach as “information-based strategy.” Beracha, before he retired as CEO of Sara Lee Bakery, simply kept a sign on his desk reading, “In God we trust; all others bring data” (a quote originally attributed to W. Edwards Deming). Loveman frequently asks employees, “Do we think, or do we know?” Anyone presenting ideas for initiatives or strategies is pressed for supporting evidence. Loveman has hired into Harrah’s a number of very analytical senior and middle managers. He also listed three reasons why employees could be fired from Harrah’s: “. . . you don’t harass women, you don’t steal, and you’ve got to have a control group.”7

Loveman provides an excellent example of how a CEO—and ideally an entire executive team—who constantly pushes employees to use testing and analysis, and make fact-based decisions, can change an organization’s culture. He’s not just supportive of analytics—he’s passionate on the subject.

Without the push from the top, it’s rare to find a firm making the cultural changes necessary to become an analytical competitor. We know it’s a bit of a cliché to say that an idea needs the passionate support of the CEO or other senior general managers, but in our research on analytical competitors, we simply didn’t find any without such committed and broad support from the executive suite. We found some firms, for example, in which single functional or business unit leaders (such as heads of marketing or research) were trying to engineer an analytically oriented shift in their firms but weren’t able to sufficiently change the culture by themselves. This doesn’t mean, of course, that such an executive couldn’t lead a change like this under other circumstances, and we did find organizations in which lower-level advocates were making progress on changing the culture. Any cross-functional or cross-department change, and certainly any enterprise-wide effort, clearly requires the support and attention of executives senior enough to direct and coordinate efforts in those separate units.

How does an executive develop a passion for analytics? It helps, of course, if they learn it in school. We’ve mentioned the math teacher background of Reed Hastings at Netflix. Loveman of Harrah’s has a PhD in economics from MIT and taught at Harvard Business School. Bezos from Amazon.com was a quantitatively oriented A+ engineering and computer science student at Princeton. Fairbanks and New England Patriots COO Jonathan Kraft were MBAs and analytically oriented management consultants before taking their jobs at their respective analytical competitors. Chris Lofgren, the president and CEO of Schneider National, has a PhD in operations research. It’s obviously a desirable situation when a CEO can go toe-to-toe with the “propeller heads” in the analytical department.

However, not every analytical executive has or needs such an extensive background. Statistics and data analysis are taught at virtually every college in the land. And a CEO doesn’t have to be smarter or more quantitatively oriented than all of his or her employees. What is necessary is a willingness to delve into analytical approaches, the ability to engage in discussions with quantitative experts, and the fortitude to push others to think and act analytically.

There are several corollaries of the senior management commitment factor. CEO orientation drives not only the culture and mind share directed to analytics but also the level and persistence of the investment in people, IT, data, and so forth. It is no simple matter, as we will describe in subsequent chapters, to assemble these resources, and it can require substantial time.

Barclays’s consumer finance organization, for example, had a “five-year plan” to build the unit’s capabilities for analytical competition.8 Executives in the consumer business had seen the powerful analytical transformations wrought by such U.S. banks as Capital One, and felt that Barclays was underleveraging its very large customer base in the United Kingdom. In adopting an analytical strategy, the company had to adjust virtually all aspects of its consumer business, including the interest rates it charges, the way it underwrites risk and sets credit limits, how it services accounts, its approach to controlling fraud, and how it cross-sells other products. It had to make its data on 13 million Barclay-Card customers integrated and of sufficient quality to support detailed analyses. It had to undertake a large number of small tests to begin learning how to attract and retain the best customers at the lowest price. New people with quantitative analysis skills had to be hired, and new systems had to be built. Given all these activities, it’s no surprise that it took from 1998 to 2003 to put the information-based customer strategy in place. A single senior executive, Keith Coulter (now managing director for Barclays U.K. consumer cards and loans), oversaw these changes during the period. Coulter couldn’t have worked out and executed on such a long-term plan without clear evidence of commitment from Barclays’s most senior executives.

Large-Scale Ambition

A final way to define analytical competitors is by the results they aspire to achieve. The analytical competitors we studied had bet their future success on analytics-based strategies. In retrospect, the strategies appear very logical and rational. At the time, however, they were radical departures from standard industry practice. The founders of Capital One, for example, shopped their idea for “information-based strategy” to all the leaders of the credit card industry and found no takers. When Signet Bank accepted their terms and rebuilt its strategy and processes for credit cards around the new ideas, it was a huge gamble. The company was betting its future, at least in that business unit, on the analytical approach.

Not all attempts to create analytical competition will be successful, of course. But the scale and scope of results from such efforts should at least be large enough to affect organizational fortunes. Incremental, tactical uses of analytics will yield minor results; strategic, competitive uses should yield major ones.

There are many ways to measure the results of analytical activity, but the most obvious is with money. A single analytical initiative should result in savings or revenue increases in the hundreds of millions or billions for a large organization. There are many possible examples. One of the earliest was the idea of “yield management” at American Airlines, which greatly improved the company’s fortunes in the 1980s. This technique, which involves optimizing the price at which each airline seat is sold to a passenger, is credited with bringing in $1.2 billion for American over three years and with putting some feisty competitors (such as People Express) out of business.9 At Deere & Company, a new way of optimizing inventory (called “direct derivative estimation of non-stationary inventory”) saved the company $1.2 billion in inventory costs between 2000 and 2005.10 Procter & Gamble used operations research methods to reorganize sourcing and distribution approaches in the mid-1990s and saved the company $200 million in costs.11

The results of analytical competition can also be measured in overall revenues and profits, market share, and customer loyalty. If a company can’t see any impact on such critical measures of its nonfinancial and financial performance, it’s not really competing on analytics. At Harrah’s, for example, the company increased its market share from 36 percent to 43 percent between 1998 (when it started its customer loyalty analytics initiative) and 2004.12 Over that same time period, the company experienced “same store” sales gains in twenty-three of twenty-four quarters, and play by customers across multiple markets increased every year. Before the adoption of these approaches, the company had failed to meet revenue and profit expectations for seven straight years. Capital One, which became a public company in 1994, increased earnings per share and return on equity by at least 20 percent each year over its first decade. Barclays’s information-based customer management strategy in its U.K. consumer finance business led to lower recruitment costs for customers, higher customer balances with lower risk exposure, and a 25 percent increase in revenue per customer account—all over the first three years of the program. As we’ll discuss in chapter 3, the analytical competitors we’ve studied tend to be relatively high performers.

These four factors, we feel, are roughly equivalent in defining analytical competition. Obviously, they are not entirely independent of each other. If senior executive leadership is committed and has built the strategy around an analytics-led distinctive capability, it’s likely that the organization will adopt an enterprise-wide approach and that the results sought from analytics will reflect the strategic orientation. Therefore, we view them as four pillars supporting an analytical platform (see figure 2-1). If any one fell, the others would have difficulty compensating.

FIGURE 2-1

Four pillars of analytical competition

Of all the four, however, senior executive commitment is perhaps the most important because it can make the others possible. It’s no accident that many of the organizations we describe became analytical competitors when a new CEO arrived (e.g., Loveman at Harrah’s) or when they were founded by CEOs with a strong analytical orientation from the beginning (Hastings at Netflix or Bezos at Amazon.com). Sometimes the change comes from a new generation of managers in a family business. At the winemaker E. & J. Gallo, when Joe Gallo, the son of one of the firm’s founding brothers, became CEO, he focused much more than the previous generation of leaders on data and analysis—first in sales and later in other functions, including the assessment of customer taste. At the New England Patriots National Football League team, the involvement in the team by Jonathan Kraft, the son of owner Bob Kraft and a former management consultant, helped move the team in a more analytical direction in terms of both on-field issues like play selection and team composition and off-field issues affecting the fan experience.

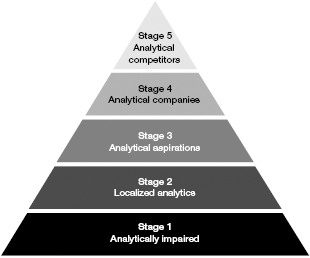

Assessing the Degree of Analytical Competition

If these four factors are the hallmarks or defining factors of analytical competition, we can begin to assess organizations by how much or how little they have of them. To do so, we have identified five stages of analytical competition, as seen in figure 2-2. The key attributes for each stage are listed in table 2-1. Like the well-known “capability maturity model” for software development, these stages can describe the path that an organization can follow from having virtually no analytical capabilities to being a serious analytical competitor. In chapter 6, we describe the overall road map for moving through these stages.

Stage 5 organizations are full-blown analytical competitors, with high degrees of each of the four factors described earlier. Their analytical activities are clearly in support of a distinctive capability, they are taking an enterprise-wide approach, their executives are passionate and driving, and their analytical initiatives are aimed at substantial results. Some of the firms that fall into this category include Google, Harrah’s, Amazon.com, Capital One, Progressive, Netflix, Wal-Mart, and Yahoo!, as well as several sports teams we’ve discussed. These organizations could always apply their analytical capabilities even more broadly—and they are constantly doing so—but they already have them focused on the most significant capability their strategy requires. In our sample of thirty-two firms that are at least somewhat oriented to analytics, eleven were stage 5 analytical competitors. However, we sought out firms that fit in this category, so by no means should this be taken as an indicator of their overall prevalence. From our other research, we’d estimate that no more than 5 percent of large firms would be in this category overall (i.e., half of the percentage in our survey saying that “analytical capability is a key element of strategy”; the other half would be stage 4). Most of the stage 5 organizations we discovered, as might be predicted, were information-intensive services firms, with four firms in financial services. Several were also dot-com firms. However, it’s difficult to generalize about industries for analytical competition, since we found stage 5 organizations in several industry categories.

FIGURE 2-2

The five stages of analytical competition

Competing on analytics stages model

| Stage | Distinctive capability/level of insights | Questions asked | Objective | Metrics/measure/value |

| 1 Analytically impaired |

Negligible, “flying blind” | What happened in our business? | Get accurate data to improve operations | None |

| 2 Localized analytics |

Local and opportunistic—may not be supporting company’s distinctive capabilities | What can we do to improve this activity? How can we understand our business better? | Use analytics to improve one or more functional activities | ROI of individual applications |

| 3 Analytical aspirations |

Begin efforts for more integrated data and analytics | What’s happening now? Can we extrapolate existing trends? | Use analytics to improve a distinctive capability | Future performance and market value |

| 4 Analytical companies |

Enterprise-wide perspective, able to use analytics for point advantage, know what to do to get to next level, but not quite there | How can we use analytics to innovate and differentiate? | Build broad analytic capability—analytics for differentiation | Analytics are an important driver of performance and value |

| 5 Analytical competitors |

Enterprise-wide, big results, sustainable advantage | What’s next? What’s possible? How do we stay ahead? | Analytical master—fully competing on analytics | Analytics are the primary driver of performance and value |

Stage 4 organizations, our analytical companies, are on the verge of analytical competition but still face a few minor hurdles to get there in full measure. For example, they have the skill but lack the out-and-out will to compete on this basis. Perhaps the CEO and executive team are supportive of an analytical focus but are not passionate about competing on this basis. Or perhaps there is substantial analytical activity, but it is not targeted at a distinctive capability. With only a small increase in emphasis, the companies could move into analytical competitor status. We found seven organizations in this category.

For example, one stage 4 consumer products firm we studied had strong analytical activities in several areas of the business. However, it wasn’t clear that analytics were closely bound to the organization’s strategy, and neither analytics nor the likely synonyms for them were mentioned in the company’s recent annual reports. Analytics or information was not mentioned as one of the firm’s strategic competencies. Granted, there are people within this company—and all of the stage 4 companies we studied—who are working diligently to make the company an analytical competitor, but they aren’t yet influential enough to make it happen.

The organizations at stage 3 do grasp the value and the promise of analytical competition, but they face major capability hurdles and are a long way from overcoming them. Because of the importance of executive awareness and commitment, we believe that just having that is enough to put the organization at a higher stage and on the full-steam-ahead path that we described in the first chapter. We found seven organizations in this position. Some have only recently articulated the vision and have not really begun implementing it. Others have very high levels of functional or business unit autonomy and are having difficulty mounting a cohesive approach to analytics across the enterprise.

One multiline insurance company, for example, had a CEO with the vision of using data, analytics, and a strong customer orientation in the fashion of the stage 5 firm Progressive, an auto insurance company with a history of technological and analytical innovation. But the multiline company had only recently begun to expand its analytical orientation beyond the traditionally quantitative actuarial function, and thus far there was little cooperation across the life and property and casualty business units.

We also interviewed executives from three different pharmaceutical firms, and we categorized two of the three into stage 3 at present. It was clear to all the managers that analytics were the key to the future of the industry. The combination of clinical, genomic, and proteomic data will lead to an analytical transformation and an environment of personalized medicine. Yet both the science and the application of informatics in these domains are as yet incomplete.13 Each of our interviewees admitted that their company, and the rest of the industry, has a long way to go before mastering their analytical future. One of the companies, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, has made significant progress toward analytical competition—not by striving toward the analytical holy grail described earlier, but by making more analytical decisions in virtually every phase of drug development and marketing.

Despite the implementation issues faced by stage 3 firms, because executive demand is one of the most important aspects of a company’s analytical orientation—and because sufficient interest from executives can drive a great deal of change relatively quickly—we’d put these firms ahead of those that may even have more analytical activity but less interest from executives. We refer to them as having competitive aspirations with regard to analytics.

Stage 2 organizations exhibit the typical localized analytics approach to “business intelligence” in the past—that is, an emphasis on reporting with pockets of analytical activity—but they don’t measure up to the standard of competing on analytics. They do analytical work, but they have no intention of competing on it. We found six of these firms in our study, although they would be much more common in a random sample, and perhaps the largest group.

By no means have analytics transformed the way these organizations do business. Marketing, for example, may be identifying optimal customers or modeling demand, but the company still markets to all customers and creates supply independent of the demand models. Their business intelligence activities produce economic benefits but not enough to affect the company’s competitive strategy. What they primarily lack is any vision of analytical competition from senior executives. Several of the firms have some of the same technology as firms at higher stages of analytical activity, but they have not put it to strategic use.

Stage 1 organizations have some desire to become more analytical, but thus far they lack both the will and the skill to do so. We call them analytically impaired organizations. They face some substantial barriers—both human and technical—to analytical competition and are still focused on putting basic, integrated transaction functionality and high-quality data in place. They may also lack the hardware, software, and skills to do substantial analysis. They certainly lack any interest in analytical competition on the part of senior executives. To the degree that they have any analytical activity at all, it is both small and local. At a state government organization we researched, for example, the following barriers were cited in our interview notes from April 4, 2005:

[Manager interviewed] noted that there is not as great a sense in government that “time is money” and therefore that something needs to happen. Moreover, decision making is driven more by the budget and less by strategy. What this means is that decisions are as a rule very short-term focused on the current fiscal year and not characterized by a longer-term perspective. Finally, [interviewee] noted that one of the other impediments to developing a fact-based culture is that the technical tools today are not really adequate. Despite these difficulties, there is a great deal of interest on the part of the governor and the head of administration and finance to bring a new reform perspective to decision making and more of an analytical perspective. They are also starting to recruit staff with more of these analytical skills.

As a result of these deficiencies, stage 1 organizations are not yet even on the path to becoming analytical competitors, even though they have a desire to be. Because we only selected organizations to interview that wanted to compete on analytics, we included only two stage 1 organizations—a state government and an engineering firm (and even that firm is becoming somewhat more analytical about its human resources). However, such organizations, and those at stage 2, probably constitute the majority of all organizations in the world at large. Many firms today don’t have a single definition of the customer, for example, and hence they can’t use customer data across the organization to segment and select the best customers. They can’t connect demand and supply information, so they can’t optimize their supply chains. They can’t understand the relationship between their nonfinancial performance indicators and their financial results. They may not even have a single definitive list of their employees—much less the ability to analyze employee traits. Such basic data issues are all too common among most firms today.

We have referred to these different categories as stages rather than levels because most organizations need to go through each one. However, with sufficiently motivated senior executives, it may be possible to skip a stage or at least move rapidly though them. We haven’t yet observed the progress of analytical orientation within a set of firms over time. But we would bet that an organization that was in a hurry to get to stage 5 could hire the people, buy the technology, and pound data into shape within a year or two. The greatest constraint on rapid movement through the stages would be changing the basic business processes and behaviors of the organization and its people. That’s always the most difficult and time-consuming part of any major organizational change.

In the next chapter, we describe the relationship between analytical activity and business performance. We discuss analytical applications for key processes in two subsequent chapters. The first, chapter 4, describes the role that analytics play in internally oriented processes, such as finance and human resource management. Chapter 5 focuses on using analytics to enhance organizations’ externally oriented activities, including customer and supplier specific interactions. Before we get there, we will explore the link between organizations that have high analytical orientations and high-performance businesses.