Stage 5

Construction

Chapter overview

During Stage 5 the building is constructed on site in accordance with the Construction Programme and this is where the majority of the contract administrator’s role is performed.

This chapter considers the duties and obligations of the contract administrator, as well as the roles and procedures which may arise during this stage together with the best methodologies for dealing with them to ensure that the building is completed in accordance with the Building Contract.

Irrespective of the contract administrator role, the Schedule of Services for the design team members will have set out the designers’ duties to respond to Design Queries from site, to carry out site inspections and to produce quality reports. However, on a small project it is likely that the contract administrator will be undertaking a number of these project roles.

The key coverage in this chapter is as follows:

Introduction

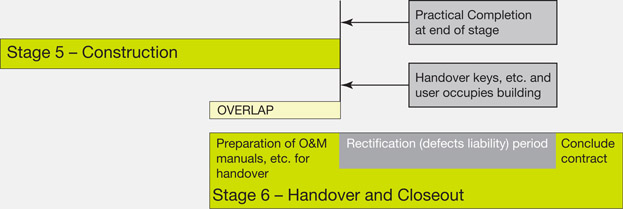

The main role of the contract administrator during Stage 5 will be to facilitate the successful monitoring of the construction process by carrying out activities between the signing of the Building Contract and Practical Completion at the end of the stage. When considering the actions needed at Stage 5 the contract administrator should be aware that there is an overlap with Stage 6, as can be seen in figure 5.1.

Therefore, during the period leading up to handover it should be noted that, because of this overlap, sections of the chapter covering Stage 6 will also be relevant during the latter part of this stage.

Figure 5.1

Overlapping of actions for Stages 5 and 6

From figure 5.1 it can be seen that although Practical Completion is achieved at the end of Stage 5, the actions required to facilitate the Handover Strategy undertaken during Stage 6 starts earlier, with the assembly of information and documentation needed to certify Practical Completion. This is discussed in more detail on page 194: Stage 6.

Practical Completion will be achieved either as a single event or in a phased manner, whereby Practical Completion will be reached in stages (with contracts using the sectional completion option). The tasks and procedures in this chapter are based on a single completion date, but, should the terms of the contract require sectional completion, the same tasks and procedures should be undertaken for each section.

Unlike earlier stages, where the procurement route will impact on the tasks to be performed by the contract administrator, in Stage 5 the tasks will generally be common to all forms of procurement in respect of the contract administrator role. On design and build projects the contract administrator role will be undertaken by the employer’s agent.

The procedures generally relate to JCT forms of contract, but there are some minor variations with other forms. These have been highlighted within the chapter.

What are the Core Objectives of this stage?

The Core Objectives of the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 at Stage 5 are:

The Core Objectives at Stage 5 revolve around the offsite manufacture and onsite construction in accordance with the Construction Programme and the resolution of Design Queries from site as and when they arise.

What supporting tasks should be undertaken during Stage 5?

The Suggested Key Support Tasks noted in the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 have been devised to support the Core Objectives and to ensure that the procedures and documentation required to carry out the administration of the Building Contract are in place so that the building is completed to enable the client to take it over. At this stage the Suggested Key Support Tasks for the contract administrator are:

- Review and implement the Handover Strategy, including agreement of information required for commissioning, training, handover, asset management, future monitoring and maintenance and ongoing compilation of ‘As-constructed’ Information.

- Update Construction Strategy.

What is the role of the contract administrator at Stage 5?

The tasks required of the contract administrator vary, albeit only slightly, depending on the form of procurement. However, the contract administrator’s relationships with other parties may vary according to the procurement route.

On traditional contracts the contract administrator should always act in a fair and reasonable manner and must be impartial in dealings with the client and the contractor. In contrast, on design and build projects, the contract administrator (the employer’s agent) is not impartial as their authority comes from the client (as the employer), not the contract. Furthermore, on the different forms of management contract the contract administrator is again an independent consultant, but the contractual obligations differ from the traditional form and the contract administrator’s roles and responsibilities should be fully described in the Building Contract.

In traditional forms of contract the contract administrator is appointed as a third party consultant to act on the client’s behalf, undertaking a number of administrative functions which will include the following Stage 5 tasks:

- administering the contract and Change Control Procedures

- checking specialist drawings for contractor’s designed portion

- seeking instructions from the client in relation to the contract

- issuing instructions, such as variations or relating to prime cost sums or defects

- chairing construction progress meetings

- preparing and issuing construction progress reports

- coordinating and implementing site inspections

- considering claims and extensions of time

- evaluating payments and issuing interim certificates

- agreeing commissioning and testing procedures

- agreeing defects reporting procedures

- ensuring that project documentation is issued to the client

- issuing certificate(s) of Practical Completion.

Once the Building Contract is entered into both parties will have rights, duties and obligations. The contract administrator should check the relevant standard form of contract, which will set out the procedures and processes that must be observed.

The contract administrator should have a robust and efficient system for monitoring the project and for logging and following up outstanding information. This will also provide evidence to show that the project has been managed properly – according to the RIBA Insurance Agency, one-third of all professional indemnity insurance (PII) claims relate to contract administration.

The time limits for the issue of certificates, notifications, etc. stipulated within the contract are crucial and the contract administrator should adhere strictly to these to avoid the contract becoming ‘at large’. If that happens, the client is unable to claim liquidated and ascertained damages from the contractor, which could lead to a claim against the contract administrator.

Time at large

The vast majority of construction contracts include a date by which the works described in the contract should be completed: the date for Practical Completion.

The term ‘time at large’ describes a situation where no date has been set for completion, or where the date for completion has become invalid, thus the contractor is no longer bound by the obligation to complete the works by the date set.

If there is no clear completion date set or if the contract does not allow the construction period to be extended then time is at large from the outset. Alternatively, where a completion date was set by the contract, time can also cease to apply either by agreement or by an intervention, such as an instruction for additional work that would take the project over the agreed timescale and for which the client has not allowed additional time.

The contract administrator (on traditional contracts) has a function independent of both the client and the contractor. That said, the contract administrator effectively has a dual role as they are also the employer’s agent.

This dual role can sometimes give rise to conflicts. A typical example would be where the client, wanting to limit their cash flow, looks to the contract administrator to under-certify or not agree to a fair and reasonable price for additional work when putting together the final account. Such interference by the client, preventing the contract administrator from acting fairly in contractual matters, will cause the client to be in breach of contract. It is therefore of great importance that the client is fully aware of this and that the contract administrator manages the position openly and correctly.

However, this impartiality has a major benefit for both the client and the contractor as either party may challenge any decision made by the contract administrator.

Where do the contract administrator’s obligations lie?

Often, the client sees the contract administrator as their tool for punishing the contractor, whereas the contractor largely understands the role of the contract administrator and has much greater knowledge of the contract administrator’s obligations under the terms of the Building Contract.

In reality it is a difficult balance, particularly as the contract administrator’s appointment rests with the client. However, the client must be made fully aware that in respect of administering the terms of the contract, the contract administrator must sit ‘squarely in the middle’.

What is the role of the employer’s agent on a design and build project?

In construction the term ‘employer’s agent’ is used to describe an agent acting, on behalf of the employer, as the contract administrator for design and build contracts. The employer’s agent is likely to be either the project lead or the cost consultant; however, the role can be carried out by someone from the client organisation, such as an in-house project manager, or by an independent project manager appointed by the client.

After the contract has been awarded, the employer’s agent’s role as contract administrator during Stage 5 includes:

- issuing instructions

- coordinating the review of information prepared by the contractor

- considering items submitted by the contractor for approval, as required by the Employer’s Requirements

- managing Change Control Procedures

- reviewing the progress of the works and preparing reports for the client

- validating or certifying payments

- considering claims

- monitoring commissioning and inspections

- arranging handover

- certifying Practical Completion.

What administration system could you use?

The contract administrator should have a robust and efficient system for administering the Building Contract based on the particular form of contract selected. The examples shown later in this chapter are based on the RIBA Contract Administration Forms for use with the JCT Standard, Intermediate, Minor Works and Design and Build contracts. They are issued in hard copy or electronic formats using NBS Contract Administrator. Further guidance and detailed information can be found by contacting the NBS:

Contact details for other contract forms are available from the contracts’ publishers (see page 46).

What are the tasks and procedures before work starts on site?

Following the successful tendering and appointment of the contractor at Stage 4 (or earlier) and before the work starts in earnest on site, the contractor will be mobilising and organising the resources required or organising any offsite manufacturing. The contract administrator should allow the contractor a reasonable time to prepare as it can be counterproductive if the contractor starts on site too soon after being appointed.

At the commencement of the stage the contract administrator should advise the client, as the employer under the contract, of their role and their responsibilities for the works on site, which may vary according to the type of procurement. These should include:

- ensuring that the site will be available on the date set for the commencement of the contract works – if it is not, there may be repercussions for the contractor, leading to an immediate delay to the Construction Programme

- I ensuring that the construction phase plan required under the CDM regulations is sufficiently advanced, otherwise work cannot start on site

- ensuring that works are insured

- knowing the level of involvement they should have with the contractor on site and the implications of giving instructions other than through the contract administrator

- ensuring that payments are made to the contractor in accordance with the timescales set, following the issue of certificates by the contract administrator

- organising and paying for materials, products and services which are outside the scope of the main contract, such as specialist installations, fittings, etc.

- understanding procedures for accepting handover at Practical Completion.

Insurance requirements for the project will have been discussed with the client prior to tendering. Before construction commences the contract administrator must ensure that the necessary insurances are in place. The wording for the insurance requirements should be checked in the particular form of contract being used, but it will generally fall into one of three categories:

The contract administrator should obtain evidence that the above insurances are in force for the duration of the project, together with the details of the contractor’s public liability insurances. The dates for renewal should be noted – if they expire before the contract completion date then the party responsible for the insurance should be asked to provide renewal certificates at the appropriate time. As soon as possible after the contractor has been appointed the contract administrator should arrange a pre-contract meeting to introduce the contractor to the client and all the other members of the project team

Figure 5.2

Indicative pre-contract meeting agenda

and endeavour to establish a good working relationship between them. In many instances they may not have worked together before and this may be the client’s first project. If the meeting occurs too close to the date for commencement there may be insufficient time for the contractor to fully mobilise. The contract administrator should issue an agenda, chair the meeting and issue concise and accurate notes as soon as possible after the meeting (see figure 5.2). After the introductions, the first item on the agenda is to confirm the contract sum and the timescale. In many cases the contract sum will be the tender figure, but in other instances the tender sum may have been adjusted. This may be because of errors, additions or agreed post-tender cost reductions and should be set out as in the contract documents. At this point the contract administrator should issue the documentation for construction in a pre-agreed format, such as architect’s instructions forms, and agree the procedures for the issue of subsequent instructions. The issue of further information required by the contractor or, in the case of management contracts, any modifications to the information release schedule prepared in Stage 4 should also be agreed. It is important that communications routes are agreed. The contractor should be advised that only formal instructions issued or countersigned by the contract administrator are valid and that all verbal instructions will be confirmed by a written instruction. A difficulty often encountered is that the contractor will ask the client directly for instructions, or the client will issue instructions directly, particularly when the client is on site or lives there. Action should be taken to prevent this. Although the client may agree to something, they may not fully understand the time or cost implications. A simple example is if the client wants an electrical socket moving there is unlikely to be any time or cost implication if it hadn’t been fixed but, if it had, the client will be liable for the time and cost in moving it. It may not always be possible to avoid this situation, but it should be reflected in the minutes to the pre-contract meeting by saying:

Similarly the contract administrator should advise that:

Small project pre-contract meetings When preparing for the pre-contract meeting a handy tip is that you can pre-draft most of the minutes as many of the items to be discussed are common to all projects and so can be adapted to suit the specific job. On small projects, the contractor is likely to have been through the process before, but that should not prevent the contract administrator from going through the full agenda as a reminder. In any event, particularly with small domestic projects, it should be remembered that the client may not have commissioned a building project before.

The minutes of the meeting should be distributed to all present and any other agreed parties as soon as possible after the meeting, with a note to say that if anyone has any comments or amendments then they should respond within seven days. If there are any amendments then the minutes should be reissued immediately after the seven days have expired as a true record. In most cases, particularly with smaller projects, the pre-contract meeting will be held on the site rather than in the client’s or consultant’s offices. When the meeting is held on site, a site walk around should be conducted immediately after the formal meeting to resolve any queries arising in the meeting relating to access, site set-up and so on, so that any subsequent decisions can be recorded in the meeting minutes. On larger projects the contract administrator should consider subsequently meeting with the contractor before the work starts to address any outstanding site matters from the pre-contract meeting.Checking insurances

Arranging the pre-contract meeting

What is the Construction Programme?

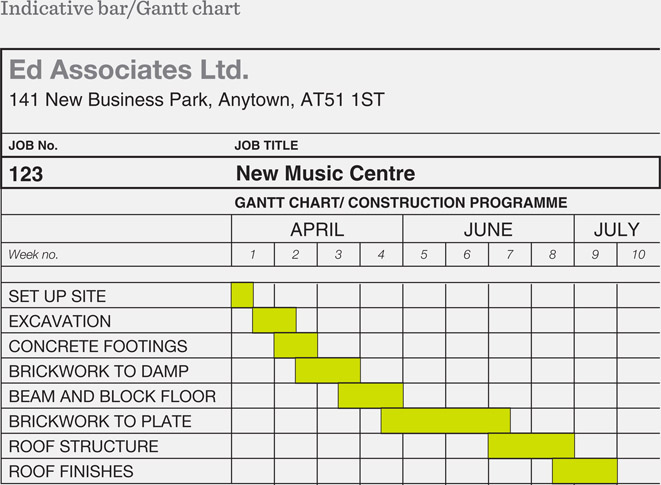

Construction Programmes describe the sequence in which tasks must be carried out so that a project (or part of a project) can be completed on time. Construction Programmes will identify dates and durations allocated to tasks. They can range from a simple bar (or Gantt) chart (see figure 5.3), through to a critical path analysis, where a sequence of critical tasks – upon which the overall duration of the programme is dependent – is highlighted. The critical path shows those activities that must be completed in a specific order so that the project can be completed on time. The critical path is usually shown as a series of lines and circles, with each circle representing an activity that needs to be completed and each line showing the relationship between two activities. The critical path will be the longest sequence of activities through the diagram, and will show how long a project is expected to take – assuming the scope does not change and everything goes according to plan.

Figure 5.3

Indicative bar/Gantt chart programme

For a Construction Programme to be effective, it must be used by the parties as a tool to help plan activities, monitor progress and identify where additional resources may be required.

The contractor’s Construction Programme schedules all the construction activities based on their timescales, paying particular attention to: elements with long lead-in times; pre-contract works, such as demolition and site clearance; prefabricated elements; works outside the main contract, phasing and sectional completion.

Programmes can also incorporate the information release schedules to set out when the contract administrator and design team need to issue Technical Design information to the contractor in order for the works to progress. On design and build or management contracts, the programme should also indicate when information produced by the contractor’s design team or specialist subcontractors should be issued to the contract administrator for comment and integration into the overall design.

The contract administrator should keep the Construction Programme under review, and report progress to the client on a regular basis, but not less frequently than at each site meeting.

The contractor’s Construction Programme is not typically part of the contract documents and so is not enforceable under the Building Contract. The contract completion date, however, is enforceable and failure by the contractor to meet the completion date may lead to a claim by the client for liquidated damages. It should be noted that the completion date indicated on the contractor’s Construction Programme may be earlier than the completion date entered in the Building Contract, to allow the contractor some float during the contract period. Indeed, it is not unusual for the contractor to produce two programmes: the formal one, which is issued to the client and the contract administrator, and the one to which they are working on site, which shows an earlier completion date.

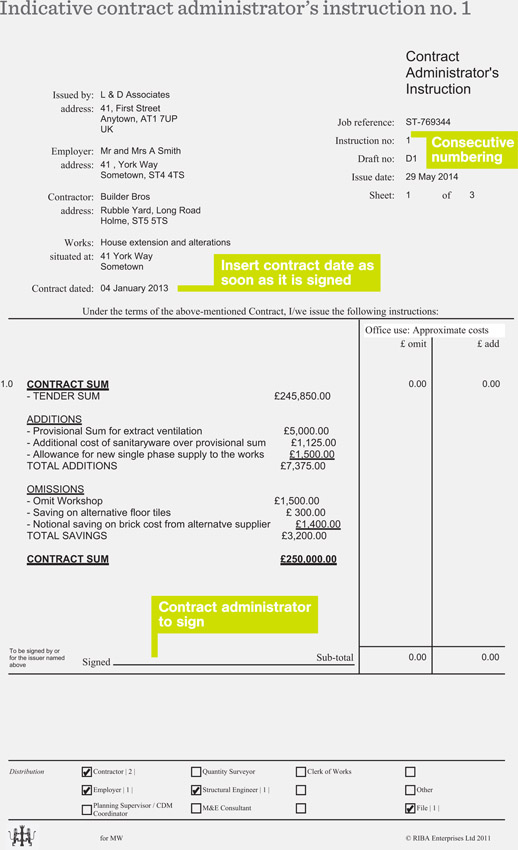

How is the contractor instructed?

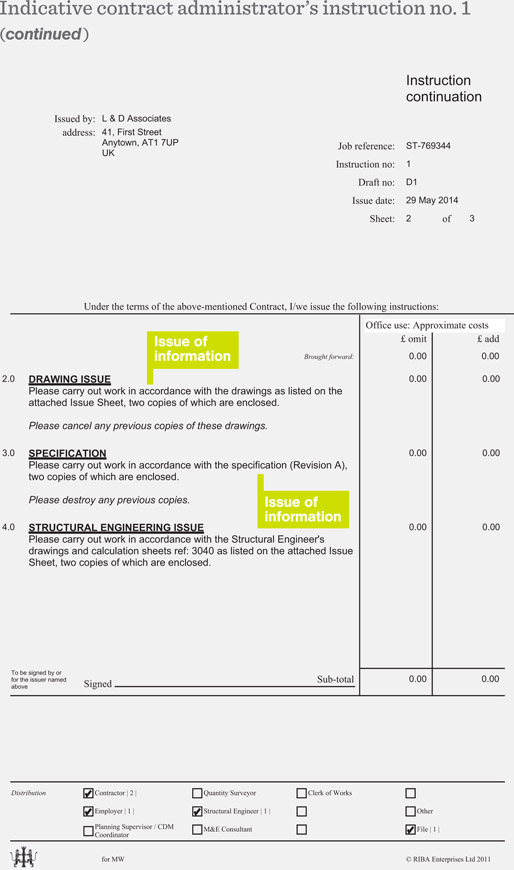

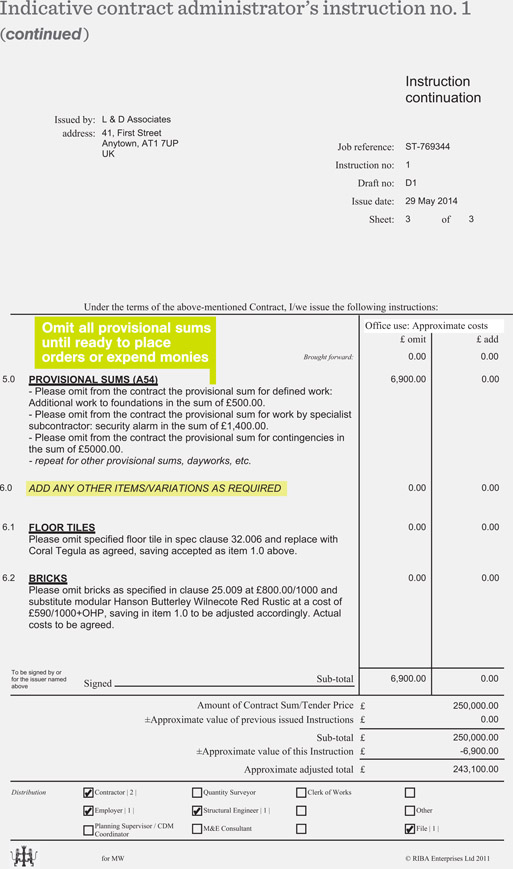

Formal instructions, historically known as architect’s instructions, are issued by the contract administrator to authorise the contractor to carry out the duties associated with the contract. On design and build projects, only the client (the employer) or the employer’s agent has the power to issue instructions. All instructions must be in writing, therefore a standard form is preferable to a letter (see figure 5.4). When issuing instructions the contract administrator needs to be aware that they can have a number of consequences, such as varying the design, increasing the amount of work and adding to the overall costs. Under the terms of the Building Contract, the contractor must comply with these instructions.

All instructions must be in writing and all verbal instructions should be confirmed by the contract administrator within seven days. If a verbal instruction is not confirmed by the contract administrator then the contractor should confirm it within the seven-day period, following which the contract administrator has a further seven days to dissent. If the contract administrator does not dissent then the instruction takes effect from the date of the contract administrator’s notification. That said, if no one confirms and the contractor does the work, the instruction can be issued retrospectively, before the issue of the final certificate, but this should be avoided.

Instructions can be issued for a number of reasons, including:

- discrepancies

- issuing of further drawings and revisions

- expenditure of provisional sums

- variations in the works

- notification of defects arising either before or after Practical Completion

- confirmation of verbal instructions

- to open up work for inspection.

If the instruction varies the work the contract administrator should ideally have the work priced before issuing the instruction or the works described in the instruction should not commence until costs have been agreed.

All instructions should be numbered consecutively and should be worded to avoid the possibility of ambiguity in their interpretation.

The original instruction should be sent to the contractor, with duplicate copies sent to the client and the other design team members, including the cost consultant where employed, as agreed at the pre-contract meeting. They should be signed by the contract administrator before issue and can be issued in hard copy or, more commonly, by email as a PDF.

Contract administrator’s instruction no. 1, which should preferably be handed over to the contractor at the pre-contract meeting, should confirm

Figure 5.4

Indicative contract administrator’s instruction no. 1

the contract sum and issue further copies of the construction drawings and specification. If the drawings have been updated since the tender, change control would be required if there has been a variation to ensure that the cost and time implications of the change have been fully assessed. Within the contract sum there may have been a number of provisional sums and contingencies – these should be omitted from the Building Contract until such time as the relevant works are instructed.

What about the issue of instructions from other members of the design team?

During the course of the works on projects where other design team members are employed, there will inevitably be a requirement for them to issue instructions.

Design team instructions for small projects

On a small project the simplest method is for a design team member to draft their instruction and send it to the contract administrator to issue on one of their instructions. However, the contract administrator should note that the instruction comes from, say, the structural engineer, particularly if it is confirming a verbal instruction.

On larger projects it is often agreed that each consultant should issue their own instructions in a numbered sequence, but with a prefix as an identifier, eg SE/001 for the structural engineer. In such cases the contract administrator should either countersign the instruction or confirm the issue on their own instruction (as technically only the contract administrator is authorised to issue instructions and the contractor could dispute an instruction from another consultant). In this way a record of the instructions generated by each consultant can be kept together.

What are the tasks and procedures after work starts on site?

Once the contractor commences work on site it is the responsibility of the contract administrator to monitor the progress of the works and to authorise payments to the contractor.

Inspecting the works

The contract administrator’s duty to inspect should have been defined for the project within the contract administrator’s terms of appointment. On larger projects, where the contract administrator may not be responsible for the inspections, it may be other members of the project team who carry out the inspections, but the contract administrator should be informed of the details. Whoever carries out the inspections they should inspect the site and the progress of the works with reasonable skill and care. However, the term ‘reasonable’ does not mean that the inspection should go into every matter in detail nor does it guarantee that the inspection will reveal or prevent defective work. Indeed, it should be referred to as periodic inspection not supervision, as the latter has more onerous implications.

Periodic inspection and supervision

Periodic visits to site will cover visual monitoring of progress, but will not normally involve detailed checking of dimensions or testing of materials.

The contractor, on site, will supervise the work on a day-to-day basis and will be responsible for the proper carrying out and completion of construction works and for health and safety provisions on the site.

Periodic visits should be made as considered necessary and the timing and number should depend on the nature of the job – they are not exhaustive or continuous inspections. The contract administrator should make their own decisions on the most appropriate times to inspect and should not rely on the contractor for advice on when such inspections should be carried out. The contract administrator should allow sufficient time to carry out the checks properly and must not be waylaid or rushed by the contractor. However, experience shows that the degree of inspection will depend on the contract administrator’s confidence in the contractor and that it is important to set up good lines of communication with the contractor.

Another factor which can have a bearing on the frequency of visits is how far the site is from the contract administrator’s office, although the project size will also have an influence. Clearly, if it will take a few hours to get to site, it is not economic to carry out frequent inspections nor is it possible to visit the site at short notice should an issue arise. The contract administrator should take this into account when working out their fee for this stage. In any event, site visits should be made at least every two weeks for smaller projects, although monthly is more common on larger projects, particularly where there may be site-based design team members.

When the contract administrator is carrying out an inspection, the onus is on the contractor to provide safe access to the contract administrator. The contract administrator should always insist that safe access is provided, not only for their own safety, but also to check that the work is done properly. For example, the contractor should not be allowed to take down the scaffolding without the contract administrator having carried out a full inspection of the roof. However, the contract administrator should inspect the work in a timely manner to avoid delaying the dismantling of the scaffolding by the contractor.

The contract administrator should ensure that the contractor gives notice of when any work will be covered up, to enable the contract administrator to inspect the work before it is hidden.

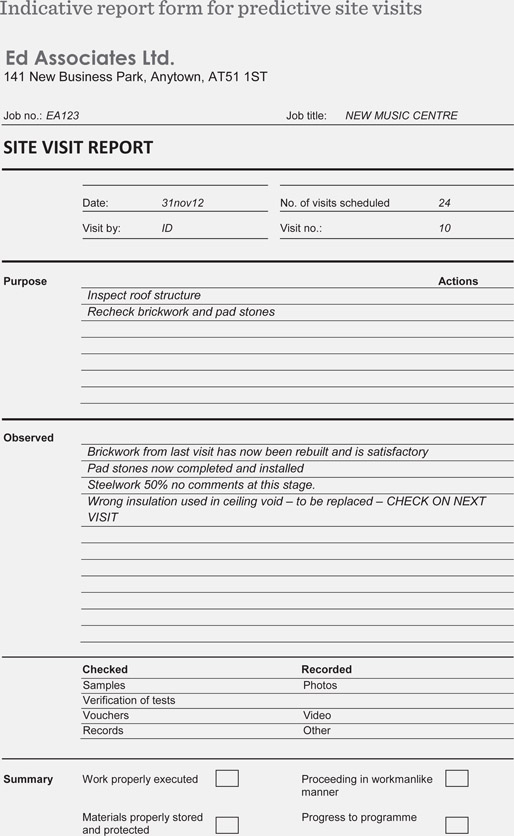

Depending on what is stated in the Schedules of Services, inspections can comprise predictive visits, periodic inspections and spot checks. The contract administrator should prepare a list of all parts of the design that it is essential to check and, before each visit, review the drawings and check any previous notes.

The contract administrator should always make careful notes of inspections and write a short report or prepare a list. A checklist, adapted to the particular project, is a useful tool and acts a reminder when on site. It is good practice to have a standard form for recording visits (see figure 5.5), which can be used on site as an aide memoire. The following items should also be considered and noted:

- the quality of completed work

- the progress of the work in relation to the Construction Programme, including the start and completion dates of sections of the work

- queries from the contractor and answers given

- the weather conditions, where they may affect progress

- resolution of nonconformities, which are to be confirmed in writing

- any other factors which may affect the progress or quality of the work.

Figure 5.5

Indicative report form for predictive site visits

Figure 5.6

Indicative form for defective works

Report forms should be filled in during the site inspection and any defects noted (figure 5.6). At the end of the project these forms will build up a picture of any issues which have arisen.

Towards the end of the contract period the contractor will ask the contract administrator to prepare ‘snagging lists’ to assist the contractor to get the building ready for handover. This should be resisted as it is wholly the contractor’s responsibility to have the building ready for the handover. Many contract administrators do still prepare snagging lists – this can be a time-consuming task, so if it becomes apparent that the building is not ready for handover then the contract administrator should terminate the inspection. However, it can still be useful for the contract administrator to go around with the contractor to point out specific items, but they should leave the obviously incomplete items to the contractor to complete.

What is snagging?

‘Snagging’ does not have an agreed meaning – it is a slang expression, not a contractual term. However, it is widely used to refer to the process of inspection necessary to compile a list of minor defects or omissions in building works for the contractor to complete, put right before Practical Completion or include with the Practical Completion certificate.

Depending on the nature of the project there may also be a requirement for inspections by other consultants, particularly where these are of a specialist nature and outside the detailed knowledge of the contract administrator. These should be reported in the same way as the contract administrator’s inspections, with copies of the reports passed to the contract administrator.

Site inspections

Further guidance and detailed information on inspecting works can be found in the RIBA Good Practice Guide: Inspecting Works by Nicholas Jamieson (November 2009).

In addition, on large projects a full-time resident consultant team or a clerk of works may be employed to monitor work on site. It is the duty of the clerk of works to assist the contract administrator by observing, inspecting, checking and reporting to the contract administrator on a regular basis and to keep a site diary. Their role might include:

- witnessing tests

- monitoring progress against the Construction Programme

- assessing whether the works comply with legal requirements, such as health and safety legislation

- assessing whether the works are being carried out in accordance with the contract documents, including taking measurements and samples if necessary

- monitoring site conditions and providing weekly reports to the contract administrator

- attending construction progress meetings

- keeping records of progress, delays, weather conditions, details of information received, deliveries, health or safety issues or any other significant events.

What about Design Queries?

Design Queries can be raised by the contractor at any time, whether verbally during site inspections, by phone or email or via formal query sheets. Design Queries are typically either requests for information (RFI) or technical queries (TQ). Many contractors will produce formal query sheets to help them keep track of any responses. On receipt of a query sheet, the contract administrator should seek a response from the appropriate design team member as soon as possible, complete the query sheet, date it and return it to the contractor. Design Queries generated by the contractor can arise for a number of reasons, such as errors in or clarification on the information issued, matters arising from unexpected findings on site and requests for more information. Irrespective of the nature of the Design Query, the contract administrator should record and date their answer and issue an instruction or design change notice (see figure 4.15) as appropriate.

The contractor should also give notice of any extra costs to the contract administrator, who should sign and return them to the contractor if in agreement before formally confirming them on a contract administrator’s instruction. However, if the contract administrator disagrees with notices these should be returned as ‘not accepted’.

What about checking drawings?

In addition to responding to Design Queries, the contract administrator is required to check any specialist drawings prepared by subcontractors for the contractor’s designed portion where applicable.

What are variations?

It is fully accepted that any contract, irrespective of size, is never carried out without any variations, whether additions or omissions. Variations may include alterations to the design, quantities, quality, working conditions and sequence of work. Variations are less likely to occur on design and build projects, assuming that the design and brief remain unchanged, but the client should be made aware that any changes they make could have an impact on the overall cost and timescale.

The contract administrator should keep the client fully aware of all variations which have a financial effect so there can be no grounds for complaint when the final account is being prepared. It is usually frustrating for the client to be faced with a bill for extras, whether generated by the client or the contract administrator.

A traditional contract should not only allow for expenditure on provisional sums, but also have a contingency sum to cover any unforeseen matters. The contingency sum should not be seen as a pot of money for paying for work not originally envisaged, it should be used only for genuinely unforeseen items. However, if there is contingency money remaining at a late stage in the project, when the risk of unforeseen matters arising is minimised, then it may be possible to use some of the money, but the contact administrator should still be cautious.

When the works give rise to a variation or additional work, it should ideally be priced before it is instructed, unless the delay could interfere with the regular progress of the works. In such cases the costs should be agreed as soon after the event as possible and the client notified accordingly.

Variations are often sources of dispute (either in valuing the variation, or in agreeing whether the work constitutes a variation at all) and can cost a lot of time and money during the course of a contract. While some variations are unavoidable, it is wise to minimise potential variations and subsequent claims by ensuring that uncertainties are eliminated before awarding the Building Contract.

Variations should always be issued in sufficient time for the work to be included within the building operation it affects to avoid the potential for delays. Whatever form the variation takes, the contract administrator should ensure that the agreed Change Control Procedures are complied with (see Stage 4, page 127).

Are there any limits on variations?

There are technically no limits on the number of variations with JCT contracts, but with the NEC3 and FIDIC forms of contract limits are placed on the extent of variations.

NEC3 (Option B) is a remeasurement and compensation form of contract in which the prices are based on a priced bill of quantities.

When an item is remeasured, if its quantity is different to that in the original bill and as a result the cost per unit changes, and the total remeasured quantity of that item multiplied by the original bill rate is greater than 0.5% of the total of the original bill, then a compensation event occurs, which then allows the unit price to be amended.

FIDIC forms of contract also put limitations on variations that can be instructed. If the value of the contract increases or decreases by more than 15% of the net contract sum (excluding provisional sums and dayworks) then the contract administrator can add or deduct from the contract sum a determined value upon consultation with the contractor, having due regard to their site expenses and other general overheads. Note that this 15% increase or decrease is not for a single item of work, but the total contract sum at completion.

What is the purpose of a site meeting?

Site meetings should be convened on a regular basis (usually at the same frequency as the valuations), such as on the second Thursday of each month or every four weeks. On traditional forms of contract it is usually the contract administrator who chairs the meeting, whereas on design and build and management contracts it is the contractor.

On larger projects the main contractor should chair their own technical meeting with the design team and the specialist subcontractors, often immediately prior to the main progress meeting, so that they can report the outcomes.

The meeting should only be attended by those persons involved in the project at the time. For example, once the ground works and structure are complete it is unnecessary for the structural engineer to attend.

The client or their representative is always welcome to attend – this is more common on larger projects. On smaller projects, particularly where there is not a professional client, they may not attend. In such instances the contract administrator should ensure that they speak to the client before the meeting to check on any actions from the previous meeting and to see if they have any problems or concerns. These can then be reported at the meeting. At the same time, or immediately after the meeting, they

Figure 5.7

Indicative site progress meeting agenda

can give them an update on progress in terms of:

- time: are there any changes to the completion date?

- quality: are there any issues with the materials and workmanship? I cost: have there been any cost adjustments?

An agenda should be issued prior to the meeting and, to save time especially on larger projects, each party attending should be asked to submit written reports before the meeting (see figure 5.7).

The contract administrator may decide to precede the meeting with a site visit to get a prior indication of progress since the previous visit. In general terms the meeting should primarily be to receive reports and to agree actions to be taken, not to receive and answer queries. The latter may be dealt with in ad hoc meetings, but the contract administrator should still ensure that the details are recorded.

Site meetings for small projects

In the case of small projects it is often useful to include an agenda item for Design Queries, to make the meeting more effective.

Detailed and accurate notes of the meeting should be taken by the chairperson or their representative with a separate column to indicate who is to take any action. The notes of the meeting should be distributed to all present and any other parties as agreed as soon as possible after the meeting, with a note to say that if anyone has any comments or amendments then they should respond within seven days. If there are any amendments then the notes should be reissued immediately after the seven days has expired as a true record.

What are the tasks and procedures for payments?

One of the responsibilities of the contract administrator is to issue certificates for payments due to the contractor. Except on short-term projects, the contractor should be provided with regular instalments of money to enable them to finance the work. Payment of the sums is regulated by the contract administrator, whose duty is to certify what amount is due for payment at each instalment date.

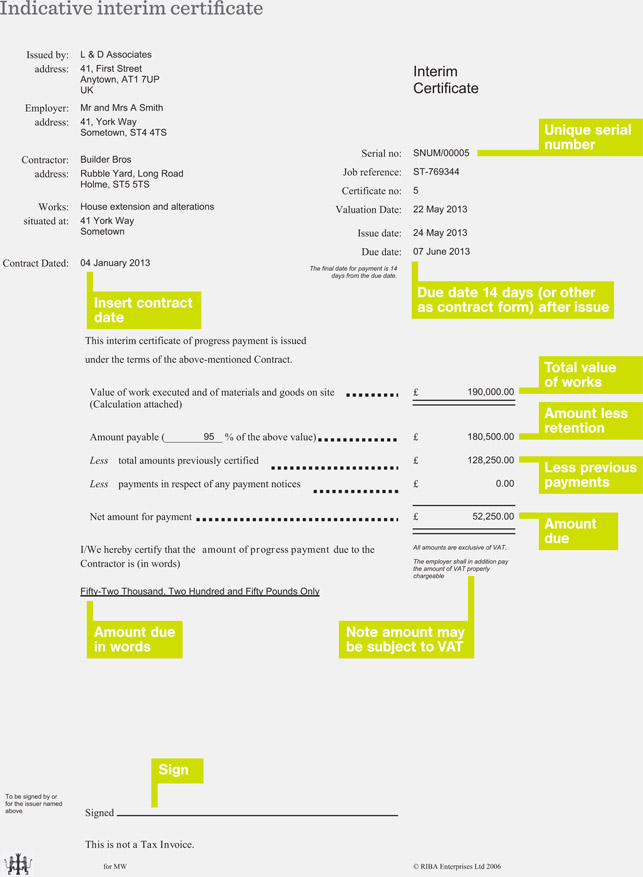

What is an interim certificate?

Interim certificates provide a mechanism for the client to make payments to the contractor before the works are complete. The Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 states that a party to a construction contract in excess of 45 days’ duration is entitled to interim or stage payments.

The contract administrator must exercise reasonable skill and care when issuing certificates to ensure that the values reflect the value of the work that has been carried out. The contract administrator must be impartial and unbiased when certifying payments – they must be satisfied that the payments are for the correct amount as it is unfair to pay less, but it is also unwise to pay more. Should the contract administrator certify too much and the contractor defaults, the client will incur additional costs to complete the works – if the contract administrator has over certified, the client could hold them liable for that loss.

Certificates for payment are known as interim certificates or certificates of progress payments, depending on which form of contract is being used, but essentially they all do the same thing, which is to instruct the client to pay the contractor an agreed sum of money at a particular time.

The contractor should submit their valuation, usually immediately prior to the progress meeting, based on the value of all the work that has been completed to that date, including any variations. Once the total is agreed by the contract administrator the amount is entered on the interim certificate less any amounts already paid with 5% retention deducted during the contract period. Once issued, the client must honour the certificate within the period stipulated by the contract, usually 14 days.

Interim certificates should state the amount of retention. A statement should also be prepared showing the retention for nominated subcontractors, if there are any. On a staged contract the statement of retention should include relevant retentions for the different stages, eg 5%, 2.5% or 0%. Some contracts may require that the retention is kept in a separate bank account and that this is certified. In this case, the client will generally keep any interest paid on the account.

There may be provision to include the value of items that the contractor has not yet delivered to site or items under manufacture or stored at works awaiting delivery. This allows the contractor to order items in good time, without incurring unnecessary long-term expense, but it does put the client at some risk if the contractor or the supplier becomes insolvent.

On design and build projects, the amounts certified as payable may be based on the contract sum analysis prepared by the contractor as part of their tender. On small projects the valuation is usually prepared by the contractor or their estimator and submitted to the contact administrator for evaluation and certification. The contract administrator should ensure that it is in a form which can be evaluated to arrive at a fair and reasonable price. Often contractors will want to be paid at the end of a construction stage, such as when the foundations are in, but these will not always fall at regular intervals. A more efficient way of being able to evaluate the works is to have the contractor prepare a spreadsheet based on the priced schedule of work and for each valuation to proportion the amount of work done in each section and to list any variations. This provides a simple and efficient way for both parties to arrive at a fair valuation.

Once the valuation is agreed, the interim certificate can be completed, as shown in figure 5.8, with the retention and previous payments deducted to arrive at the amount due, exclusive of VAT. VAT is no longer shown on most certificates as VAT may not be applicable on some projects, such as new-build housing and listed buildings, where the onus for charging VAT rests with the contractor.

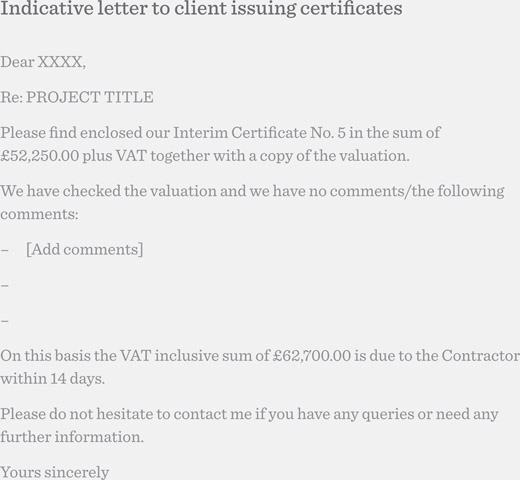

The completed certificate together with a copy of the valuation should be sent to the client with a covering letter instructing them to pay the contractor. However, for clients who are unable to claim back VAT, it is helpful to them if the VAT inclusive figure is stated on the covering letter. A suitable wording for the letter is shown in figure 5.9.

At the same time, the contract administrator should send a similar notification to the contractor with a copy of the certificate, and a copy of the valuation if it has been amended during evaluation, with a request to send a VAT invoice to the client by return for the amount due in the certificate. Under the terms of the Building Contract the client should pay on receipt of the certificate, but many clients need a VAT invoice in order to process the payment through their system.

On larger projects, where a cost consultant has been employed, the valuations are normally prepared by the cost consultant and the contractor

Figure 5.8

Indicative interim certificate

Figure 5.9

Indicative letter to client issuing certificates

together and a figure agreed. The cost consultant will then submit the agreed valuation to the contract administrator, who will process the certificate in the usual way.

The contract administrator (or cost consultant where appointed) should monitor the costs on a regular basis and give the client regular cost updates to keep them informed of any variations in the overall cost. A professional client may only be interested in the contract sum, but a smaller client may be looking at the overall cost so the reports may need to include fees and VAT.

What are dayworks?

Daywork is a means by which a contractor is paid for specifically instructed work on the basis of the cost of labour, materials and plant plus a mark-up for overheads and profit when work cannot be priced in the normal way. Daywork may be applied, for example, when unforeseen circumstances are encountered during the works or when work is instructed for which there are no comparative rates in a bill of quantities or schedule of rates.

Most contracts contain clauses that provide a method of evaluating variations, additional work and instructions by using existing contract rates and prices, but NEC contracts are based on the contractor quoting for the work (see page 168).

Daywork rates can be priced in one of two ways: by either a percentage addition, where a percentage is added for overheads, profit and incidental costs; or by the use of all-inclusive rates. All-inclusive dayworks rates are quoted at tender stage as part of the preliminaries and incorporated into the contract documents. These include an allowance for overheads and profit, either fixed for the period of the contract or, in the case of contract conditions that are index linked, subject to an inflation allowance.

What if the works are delayed?

Where works are delayed or will be delayed beyond completion and the cause of the delay is beyond the control of the contractor, including the impact of variations, the contractor may be entitled to an extension of time and, in certain circumstances, additional costs for loss and expense. Equally, the contractor may only be entitled to an extension of time with no costs attached such as in the case of delays caused by the contractor’s own domestic subcontractors.

If the contractor fails to complete the works by the date set in the Building Contract the client has the right, under the terms of the contract, to deduction of liquidated and ascertained damages, which is a pre-agreed measure of compensation. However, a number of factors may have had an impact on the delay – the contract administrator will need to assess these factors and, if appropriate, issue an extension of time certificate.

An extension of time allows the contract administrator to change the date for completion of the works or a part of the works if the contractor is delayed by certain specified events, which releases the contractor from the need to pay liquidated and ascertained damages. Conversely it also retains the right of the client to deduct or withhold liquidated damages.

The contract administrator must act lawfully, rationally and methodically to decide whether the cause of delay is a ‘relevant event’ qualifying for an extension to the contract period. The contract administrator has a duty to use a calculated approach, not an impressionistic one.

To assess whether a cause of the delay constitutes a relevant event will depend on it falling into one of the following categories:

- variations to the design and detail

- instructions issued by the contract administrator

- the implications of any discrepancies between the drawings, specifications, etc.

- suspension of the works by the contractor

- loss or damage by the perils noted in the Building Contract

- delay in possession of the site or part of the site

- delays as a result of opening up the works as directed by the contract administrator unless the works or the materials are found to be faulty

- any actions by the client, consultant team or others employed by the client which hinder the regular progress of the works

- exceptionally inclement weather

- civil commotion and terrorism threats

- force majeure/‘Acts of God’.

The award of an extension of time is solely the responsibility of the contract administrator, who must assess the time lost by the contractor so that their liability for damages is the same as if the disruption had not occurred. The contract administrator must remain firmly independent of the client in this respect.

What should the contract administrator do about delays?

Under the terms of the Building Contract, when it becomes reasonably apparent that the works are being or are likely to become delayed, the contractor should give written notice to the contract administrator of the delay and provide supplementary information to enable the contract administrator to make an assessment (see figure 5.10). However, having made a claim for lost time, the contractor is still under an obligation to use their best endeavours to make up for this lost time, even if the fault is not of their making.

The supplementary information required will be stated in the contract form, but will include the material circumstances and the cause or causes of the delay and details of any ‘relevant events’.

The contract administrator should assess and make the award as soon as is reasonably practical, but within 12 weeks of the receipt of the detailed information and certainly no later than the completion date.

On NEC3 contracts, delays are included under the term ‘compensation events’, which are any matters that could affect time, cost or quality. There is an obligation on both parties to give early warnings of compensation events. Indeed, where a compensation event arises from the contract administrator issuing an instruction, or changing a previous one, the onus is on the contract administrator to notify the contractor of the compensation event.

If events occur during the course of the works that cause the completion of the works to be delayed then these may be compensation events. Compensation events will normally result in additional payment being made to the contractor and may result in the adjustment of the completion date or key dates.

NEC3 contracts limit compensation events to those, and only those, identified in the contract. If an event is not identified in the contract as being a compensation event then no claim should be submitted, even if there has been a delay. The contract prevents the parties circumventing the contract by making a claim for damages at common law.

The NEC3 assessment system is more formalised than in JCT contracts.

- If a compensation event occurs, the contractor must notify the contract administrator within eight weeks of the event or it is time barred.

- The contract administrator must respond within one week – if the contract administrator does not respond within two weeks it is deemed that the delay is accepted.

- The contractor should then quote for the compensation event within three weeks.

- The contract administrator must respond to the quotation within two weeks.

- The contractor then has three weeks to revise the quotation if required.

- When agreement has been reached, any changes to the contract are implemented.

Unlike in JCT contracts, the assessment of the delay caused by a compensation event is final and cannot be revised later if proved to be incorrect.

NEC3 contracts also make provision for early warning procedures. Both parties must give early warning of anything that may delay the works, or increase costs.

NEC3 contracts

Further details for assessing compensation events in NEC contracts can be found in section 9 of the RIBA Good Practice Guide: Extensions of Time by Gillian Birkby, Albert Ponte and Frances Alderson (June 2008).

In the past it was commonplace for the contract administrator to delay awarding an extension of time and they would wait and see whether the contractor could make up the time or by how much they could reduce the delay. This is now unnecessary as most forms of contract allow the contract administrator a period of 12 weeks following Practical Completion in which to reassess any extensions granted and to make adjustments if necessary. This may mean extending, or even reducing, extensions already granted. Note, however, that it is best to leave the full reassessment of all extensions of time until after completion, when the full picture is known and the contract administrator can carry out a complete review, as some forms will only allow one reassessment.

How should the contract administrator assess extensions of time?

In response to the information supplied by the contractor, the contract administrator needs to build up a full picture of the situation as soon as possible. Pre-existing records should be consulted, such as:

- site progress meeting minutes, where actual or potential delays should have been recorded

- records of site delays noted

- contractor’s reports

- the Construction Programme

- method statements

- daywork sheets

- clerk of works’ reports, where one is appointed

- other team members’ records

- the as-built programme, if assessing after Practical Completion I the contract administrator’s own observations and site notes.

Instructions for variations should be issued in sufficient time for the work to be included within the building operation it affects. Therefore, the fact that a variation has been instructed will not necessarily mean that it was the cause of an operation being delayed. The objective for the contract administrator is to identify when a variation was executed and what impact it had on the building operation, based on the physical and material content of the variation.

Figure 5.10

Indicative form for recording site delays

When dealing with extensions of time, the contract administrator should remember the following:

- Respond to each and every proper notice of delay from the contractor – at least this is evidence that the claim has been considered.

- When awarding extensions of time, do so only for the causes specified in the contract. State the causes, but do not apportion. Keep full records in case the award is contested.

- Comply strictly with the procedural rules.

- Observe the timescale if one is stated in the contract. If none is stated, act within a reasonable time.

- Form an opinion which is fair and reasonable in the light of the information available at the time.

Acknowledging requests from the contractor

The contract administrator should acknowledge requests for extensions of time with the following response:

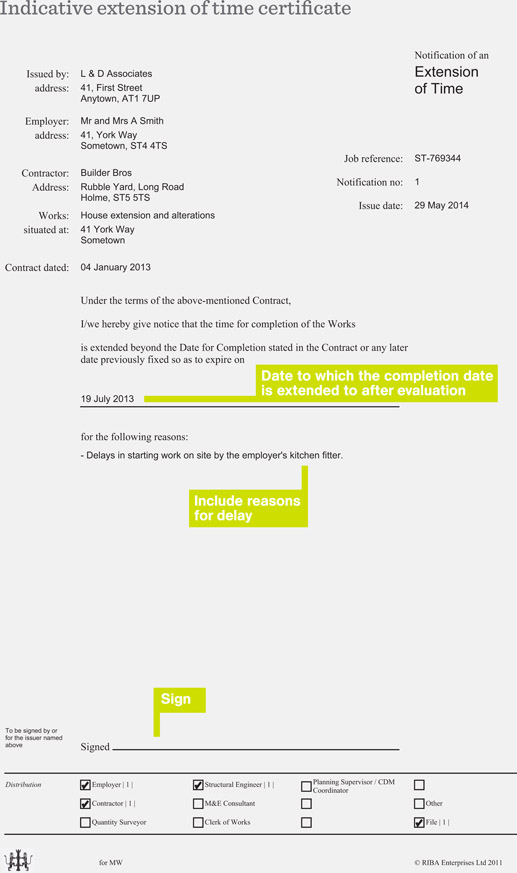

Once the contract administrator has assessed the claim, both the contractor and the client should be notified of the decision by issuing a suitable certificate, such as the one shown in figure 5.11.

On design and build forms the term ‘extension of time certificate’ is replaced by ‘notice of revision to completion date’, but the meaning and processes are the same.

When assessing any claims for extensions of time the contract administrator should be aware that the contractor may make more than one claim at a time, thus the evaluation process is more complex as some claims may attract costs and others not. These are known as concurrent delays (see below).

Figure 5.11

Indicative extension of time certificate

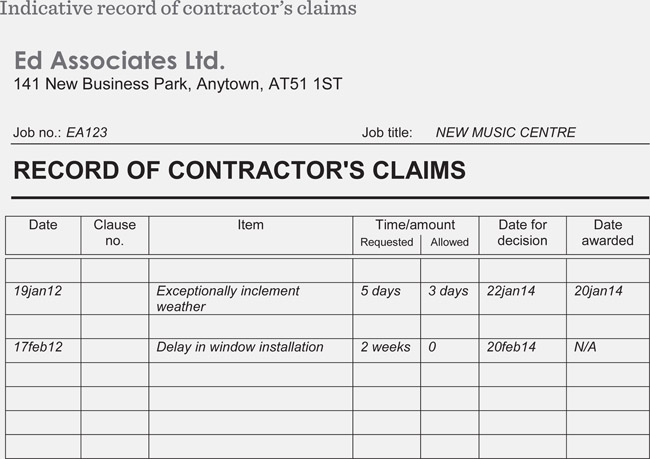

Figure 5.12

Indicative record of contractor’s claims

To assist in such cases the contract administrator should keep a record of all claims arising and the decisions made in a suitable format, such as the one indicated in figure 5.12.

Further references to the assessment of extensions of time can be found in The RIBA Good Practice Guide: Extensions of Time by Gillian Birkby, Albert Ponte and Frances Alderson (June 2008).

What is loss and expense?

At the same time as an extension of time application the contractor can also make a claim for direct loss and expense for some of the contract provisions – the terms of the Building Contract should be consulted to ascertain the actual provisions. Once the contract administrator has confirmed that the application is valid and that sufficient information has been provided, their assessment of loss and expense must be based on the following:

- There must be an actual direct loss and the costs claimed must not allow the contractor to profit as a result of the disruption.

- The works must have been materially affected.

- Disturbance to the planned work must have already occurred.

- Payment for the work cannot be made under any other contractual provision.

The awarding of an extension of time and any associated loss and expense effectively puts the contractor back in the position they would have been in had the disruption not occurred.

What are concurrent delays?

Concurrent delay is a complex term, the legal status of which remains unclear. It refers to the situation where more than one event occurs at the same time, but where not all of those events enable the contractor to claim an extension of time or to claim loss and expense, therefore the contract administrator will have to assess the balance between the individual elements. Increasingly, such analyses are undertaken by experts who specialise in delay analysis, particularly on larger projects.

What can be the effect of late information?

The contract administrator must ensure that any information issued to the contractor during the course of Stage 5 should be timely and meet the contractor’s information required schedule. Failure to do so may not only have an impact on the Construction Programme but may expose the client to a claim for an extension of time and additional costs from the contractor on the grounds of late information.

The contract administrator must avoid issuing information late as it will put them in a difficult situation. In such circumstances, the contract administrator must not be influenced improperly by any other party, and must continue to act professionally and fairly.

Conflicts of interest can arise where the contract administrator is also the designer. Part of the contract administration role is to manage errors and omissions within the design information. In such a situation it may be difficult for the contract administrator to act impartially, as decisions that they make as contract administrator may well have implications for their role as designer.

What if the contractor does not complete in time?

The date(s) for completion of construction works will have been set out in the contract particulars. However, if the date(s) for Practical Completion passes before the works are complete and the contract administrator has not granted any extensions of time, a Practical Completion certificate cannot be issued on the due date.

If the contractor is responsible for the delay and the contract administrator has not issued an extension of time, the client may be entitled to claim liquidated and ascertained damages at the rate set out in the contract particulars.

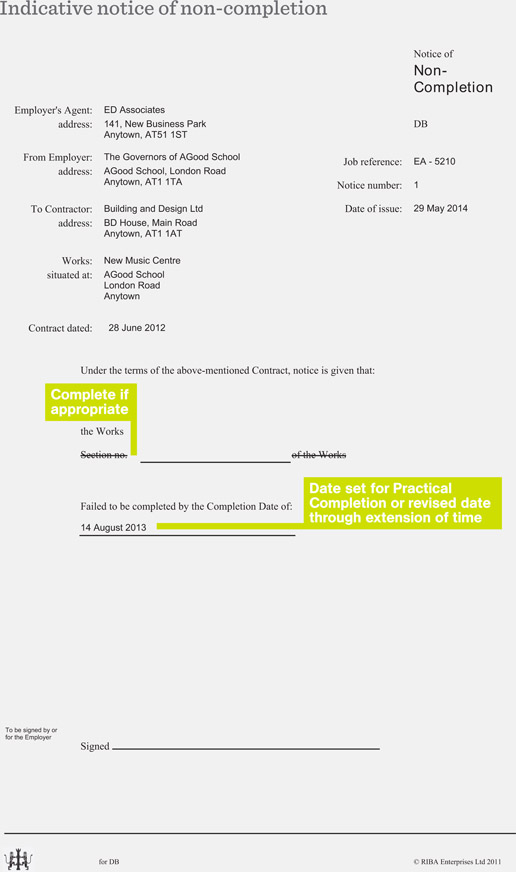

Some contracts, such as the JCT series, require that the contract administrator issues the contractor with a certificate of non-completion before the client can claim liquidated and ascertained damages. This gives formal written notice to the contractor that they have failed to complete the works described in the Building Contract by the completion date or other agreed date.

The contract administrator should have given due consideration to any applications for extension of time before issuing a certificate of non-completion. If there are subsequent extensions of time that result in the completion date being adjusted, and the contractor then fails to meet this adjusted date, a new certificate of non-completion must be issued.

On contracts with sectional completion, separate certificates of non-completion must be issued for each section that is not completed by the required date.

The client is entitled to deduct liquidated and ascertained damages from any subsequent payments due to the contractor, provided that a notice has been issued setting out the basis of the calculation. Note that this entitlement does not affect the contract administrator’s duty to assess interim certificates which should be assessed as normal, with the certificate stating the full value of the work done. The onus is on the client to deduct the liquidated damages, not on the contract administrator

Figure 5.13

Indicative notice of non-completion (design and build project option)

to reduce the certificate accordingly. The deduction can be challenged by the contractor if the procedures and the notice periods set out in the contract have not been followed.

It should be noted, however, that some forms of contract do not require a certificate of non-completion to be issued, but it is considered best practice to issue one on a standard form appropriate to the form of contract being used, such as the JCT design and build form (figure 5.13). (On design and build contracts the term ‘certificate of non-completion’ is replaced by ‘notice of non-completion’, but the meaning and processes are the same.)

What happens at Practical Completion?

When the project is nearing completion, a well-organised, efficient and effective transfer of information to the client is essential to ensure the successful handover and operation of the building, in accordance with the Handover Strategy. The period for the preparation for handover at Stage 6 precedes Practical Completion, which occurs at the end of Stage 5. The tasks and procedures relating to the preparation for handover will be dealt with in the next chapter.

What is Practical Completion?

There is no absolute legal definition of Practical Completion and case law is very complex. It has been defined as completion except for a few minor items when there are no apparent visible defects. From a practical point of view it may be acceptable to hand over the building if there are some cosmetic defects, but not if, say, the heating is not working.

Therefore, while the works may achieve Practical Completion despite the existence of latent defects (which are not known about), it should not be certified if there are patent defects. The contract administrator should be aware that patent and latent defects (see page 201 in Stage 6) are subject to different rules at law, which may be expressed in contracts, and this can cause confusion. However, there is some debate about whether Practical Completion can be certified where very minor items, which do not affect the client occupying the building, remain incomplete.

The contract administrator should certify Practical Completion when they consider that all the works described in the contract have been carried out (this is referred to as ‘substantial completion’ on some forms of contract). The issue of the certificate sets the date when the client can occupy the building and takes over responsibility for insurances. Certifying Practical Completion also has the effect of ending the contractor’s liability for liquidated damages, releasing half of the retention monies and starting the rectification period.

Practical Completion in non-traditional contracts

On construction management contracts, separate certificates of Practical Completion should be issued for each trade contract. Once certificates for all the trade contracts have been issued, the contact administrator should issue a certificate for project or sectional completion. The same is true on management contracts, where each works contract must be certified individually.

Practical Completion is not a term recognised in PPC 2000 and other partnering contracts which simply refer to ‘completion’. This is a far more open-ended term and it can put the contract administrator in a difficult position in deciding when the project becomes useable by the client. In such an instance the project may be deemed complete when the building is ready for the intended use by the client, whether it is for immediate use, such as fitting-out or actual occupation by the end users and this can be done in a safe manner without affecting warranties.

Often the contractor and the client are keen for the contract administrator to issue the certificate when more than minimal defects are outstanding. The contract administrator should be wary of bowing to either as the issue of the Practical Completion certificate could make them liable for subsequent problems, claims for which may arise from either party. This may affect a liquidated damages calculation or the premature release of retention monies, with no guarantees of when the works will be completed.

If the contract administrator has no option but to certify Practical Completion even though the works are not complete, they should inform the client in writing of the potential problems of doing so and obtain written consent from the client to do so. However, before issuing the certificate the contract administrator should also obtain a written agreement from the contractor that they will complete the works and rectify any defects.

What if the building is handed over in stages?

On large projects it is common for the Building Contract to provide for sectional completion, whereby different completion dates are set for different sections of the works. This allows the client to take possession of completed parts while construction continues on others.

Sectional completion is pre-planned and should be defined in the contract documents. The extent of each section must be clearly stated and the liquidated damages and the amount of retention that will be released must be specified for each section.

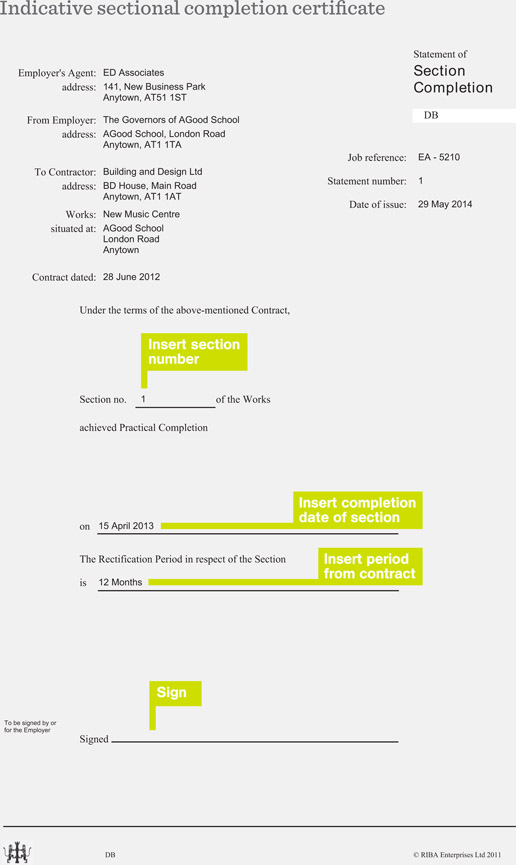

Sectional completion follows the usual handover procedures (see figure 5.14). However, it may exclude mechanical and electrical service systems, which may be reliant on total completion before they can be properly tested and commissioned.

Is partial possession different from sectional completion?

When the building is nearing completion the client or tenants may want to take possession of part of the building even if the works are ongoing or there are defects that have not been rectified. If this has not been pre-programmed as a sectional completion, the contract administrator may be able to arrange for the contractor to agree to partial possession.

The effect of partial possession is that any part for which partial possession is given is deemed to have achieved Practical Completion and half of the retention for that part must be released. The rectification period will begin for that part and liquidated damages will be reduced proportionally.

As with a single handover, the client will then be responsible for that part and should take out insurance cover for it.

The contractor is not obliged to allow partial possession (although permission cannot be unreasonably withheld) and may not wish to, particularly if it will hinder the completion of the remaining part and cost more as a result.

An alternative arrangement might be for the client to ‘use or occupy’ the works. This is different from possession in that the client does not have sole use of the works, and the contractor remains in possession, with

Figure 5.14

Indicative sectional completion certificate

responsibility for insurance and so on. However, care should be taken with this option because of the possibility of the client occupying areas adjacent to, or only accessible through, the ongoing construction works.

Note that NEC3 has a different description of partial possession as ‘taking over’ the works.

What are the tasks and procedures at Practical Completion?

The tasks and procedures leading up to Practical Completion and the assembly of the necessary documentation ready for handover are dealt with at Stage 6.

The main contractor should give the contract administrator due notice that the building will, in their opinion, be ready for Practical Completion by a certain date. During this time the contract administrator should be carrying out their regular inspections to assess whether this is likely to be the case or not. The contract administrator should not, as explained earlier, provide snagging lists for the contractor as this is the responsibility of the contractor.

The pre-handover meeting (see page 197: Stage 6) should be arranged, at which the procedures and date for handover should be agreed.

By the date agreed for the Practical Completion meeting the contract administrator should have arranged for any other consultants to carry out their own inspections and to provide lists of any remaining defective and outstanding items to accompany the certificate.

The Practical Completion meeting should be attended by the client, and other consultants should attend in case they are required to answer queries. There should be a walk-round of every room in the building with the contract administrator making notes of defects as required. Once all parties are satisfied that the works are substantially complete and suitable for occupation, the client should accept the building and the keys should be handed over together with the maintenance and other documentation. Meter readings should be taken as necessary and the contractor should leave the site clear of all plant, etc.

Note that in the case of larger, more complex buildings, handover may occur over a period of a week, so that every room can be inspected before the final handover meeting.

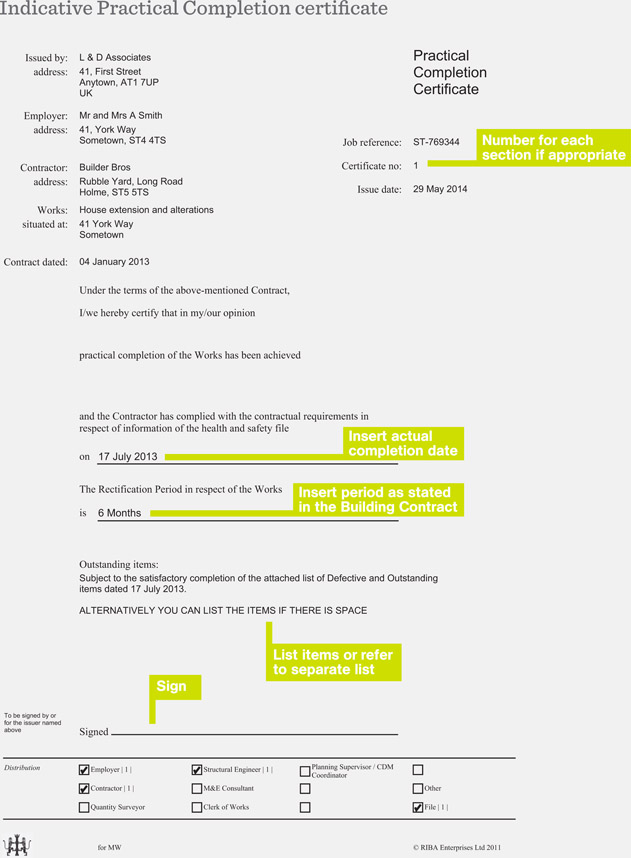

Figure 5.15

Flow chart for tasks and procedures at Practical Completion

Figure 5.16

Indicative Practical Completion certificate

What are the tasks and procedures for issuing the Practical Completion certificate?

Figure 5.17

Indicative letter to contractor following Practical Completion

Once the building has been officially handed over, the contract administrator should assemble their list of defective and outstanding items at Practical Completion, including any items received from other consultants. The Practical Completion certificate appropriate to the form of contract used should be completed with the completion date and the date for the end of the rectification period (see figures 5.15 and 5.16).

There may be provision on the certificate to list the defects, but it is more practical to attach the list and add a statement to the form such as ‘subject to the satisfactory completion of the attached list of defective and outstanding items dated [xxxx]’.

Contractor notification and advice

Original certificates signed by the contract administrator should be issued to the contractor together with the list of minor items to be immediately rectified, with copies sent to the client and the other consultants.

Figure 5.18

Indicative letter to client following Practical Completion

The certificate should be issued with a letter, such as that shown in figure 5.17, outlining the contractor’s responsibilities during the rectification period.

Client notification and advice

The client should be advised of their responsibility to insure the building. It is prudent also to advise the client of what actions they should take if there are any matters relating to defects matters which arise before the end of the rectification period. A suitable form of words is noted in figure 5.18.

The tasks and procedures assume that there is a single handover, but in the case of sectional completion or partial possession, these tasks should be undertaken for each section.

Chapter summary 5

This chapter has demonstrated the tasks and procedures to be undertaken by the contract administrator during the construction process leading up to the Practical Completion of the works, when the client is able to take possession.

Other members of the project team will be undertaking other roles during this period, but the contract administrator is responsible for coordinating their work to ensure the satisfactory completion of the building.

Throughout this process the contract administrator must be methodical and thorough in the procedures to be undertaken, and must keep adequate records to provide an audit trail should any subsequent problems arise.