Chapter 1

BECOMING A BETTER LEADER

The Basics

We're blind to our blindness. We have very little idea of how little we know. We're not designed to know how little we know.

—Daniel Kahneman

The ballots were all counted.

Final score: 38–6.

Thirty-eight votes to six!

And it wasn't me that won the 38. It was my opponent. How could this be?

…I lost? For real?

Wow!

Only six votes?

I sat in a puddle of disbelief.

That can't be true!

But it was true. When all was said and all was done, I'd lost.

By a landslide.

I'd been creamed.

This all happened in 1999, but it seems like yesterday.

I was living in New York City, where I was hoping to become the new executive director of a nonprofit leadership development organization. At the annual meeting the members elected new officers.

In my mind, I was a shoo-in for the job. No one else had worked as tirelessly as I had. No one else had the “feet on the street” experience that I had. No one else was more passionate than I was.

Committed to the cause, I was a “super-volunteer.” I'd put in countless hours, doing anything and everything. The outgoing executive director had called me the organization's newest rising star.

I had one competitor for the job: Gary.

Gary was a newbie: he'd just joined in the past year. Gary owned his own business in the construction industry, where he'd been quite successful. However, when it came to our nonprofit, he was still green.

Yet, somehow, Gary had trounced me. He'd captured more than 85% of the vote.

What was his secret? How had he done it?

I wouldn't find out how he managed to beat me so soundly for another month. It took me that long to set up a meeting with Gary—and not because of a busy schedule. It was my ego. I couldn't face Gary. My pride was too hurt. I needed some time to lick my wounds before I could look him in the eye.

On a blustery gray day in early December, Gary and I finally met up for lunch. We met at the Galaxy Diner, a bustling spot smack dab in the middle of Hell's Kitchen. The Galaxy is a classic New York diner, where the size of the menu is only outdone by the size of the portions. The waitresses seem like they've been working there since diners were first invented.

After some small talk and minestrone soup, I casually told Gary how surprised I was about the outcome of the election. I asked him if he was surprised as well.

“No,” he answered easily.

I was taken aback. He was serious. What did he know that I didn't know?

“How did you know that you'd get all those votes?” I asked him—expecting a quick, one-sentence answer.

I couldn't have been any more wrong.

Gary's response shocked me. He had thought this whole thing out:

I reached out to people. I invited people out to coffee and to lunch. I got to know them. I asked them how long they'd been active in leadership development and with our nonprofit. I asked them what they liked about the organization. I asked them what they would change if they could. I asked them what they hoped the future might look like.

Then, I shared why I was running for executive director. I told them how important this work is to me. I told them that I wanted to build a team of people to take this organization to the next level. I asked if they'd be a part of that team.

Finally, I asked them to show up on election night and vote for me, so that we could be the team to make things happen.

As Gary finished, I felt lightheaded. I propped myself up on the red cushion of the booth.

His explanation made perfect sense. In fact, it was so perfect that it hit me like a blinding flash of the obvious.

Why hadn't I done that? Why hadn't I done anything even close to that?

I'd been living in a fantasy world. Whether you call it inexperience or ignorance, I had just expected to be elected. In hindsight, I could see that I'd made a whole lot of assumptions:

- People in the nonprofit would know about me.

- They would have heard about all the hard work that I had done on behalf of the organization for the past few years.

- All my previous efforts would speak for themselves.

- People would know who the “best” candidate was.

- People would vote based on merit.

- I'd “earned” the job, based on my excellence and tenure.

- People would vote for me.

Given my boatload of assumptions, I never even considered taking the step of actually asking people to show up and support me. So I hadn't. And, except for five other people, they didn't.

Ask for votes? Be that explicit? It wasn't my style. It seemed so weird. So…direct.

But Gary knew something I didn't.

Gary knew that the key to successful leadership is influence, not authority. He wasn't interested in acquiring a title and throwing the weight of the position around. Gary knew that no one wanted to work under an authoritative leader.

The whole organization ran on the backs of volunteers. We felt connected to the mission and vision of the organization. Everyone was there out of commitment, not compliance. We did things because we cared. We offered our time, talents, and efforts because we wanted to, not because we had to.

As a volunteer, working from commitment had fueled my own journey for the past three years. However, as a candidate for executive director, I'd fallen for the leadership trap of my own ego.

My fantasy of becoming the person “in charge” had intoxicated me with visions of grandeur. I'd become aloof and had neglected the principles that really mattered. I'd already envisioned how everyone else would fall in line and do what I wanted them to do. I thought I was entitled to lead. This version of reality was crystal clear in my imagination. Sadly, I was blind to the greater truth.

Gary, however, knew that leadership isn't about what goes on in the mind of a leader: it's about what goes on in the minds of people they want to lead. Understanding how things really work, Gary tapped into their energy and explicitly asked them to show up and vote for him. And show up they did. And I lost.

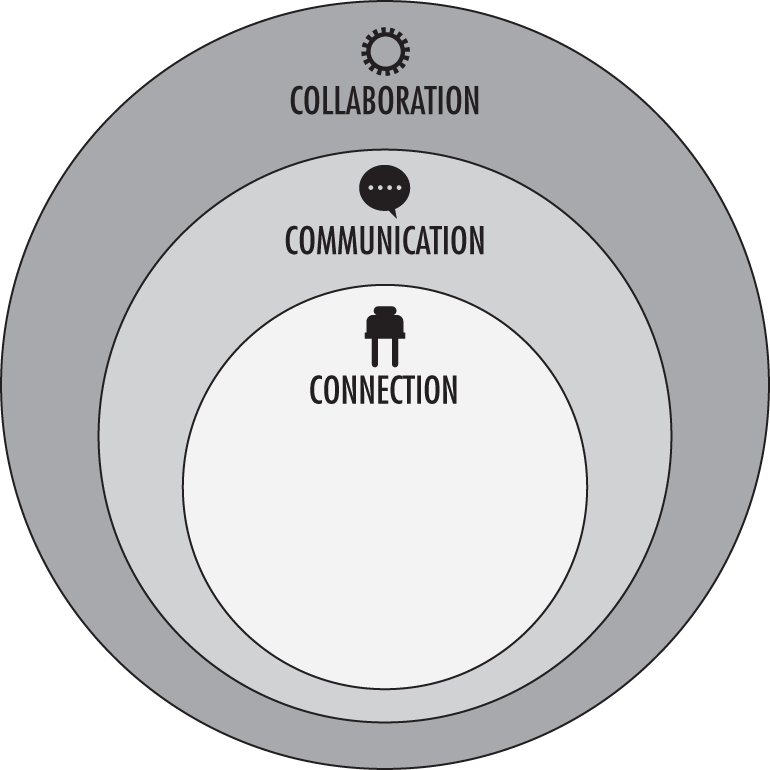

The experience was incredibly humbling. However, that defeat turned out to be one of the most valuable lessons of my life. Gary, through his modeling, had provided me with a map of how to become a better leader (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Core Components of Being a Leader

The loss to Gary burst the bubble of my ignorance. I suddenly realized that there was a lot about leadership that I didn't even know that I didn't know. In preparing and executing his election victory, Gary modeled three essential leadership principles: connection, communication, and collaboration.

CONNECTION

Invisible threads are the strongest ties.

—Friedrich Nietzsche

When you connect with people on a personal level, they feel that you care about them. Connection provides the spark that gets others to willingly follow your lead. It's the main ingredient in trust. Think of Gary's decision to invite members of the organization out to coffee and/or lunch. He made the members feel valued, and he sent a clear message that he wanted to get to know and understand them. Connection doesn't come cheap; you need to give of your time and attention. However, your investment pays dividends of engagement and commitment.

There's a simple yet powerful exercise I've done with dozens of groups to demonstrate the importance of connection to become a better leader.

Let's try it together right now.

Grab a pen and paper and think of the best leader you've ever worked with. It can be a work leader, school leader, sports coach, and so on. Make a list of qualities of that leader. What made them so great? Come up with at least 10 qualities.

Now review those qualities. Place each quality into one of these three categories:

- Intelligence/smarts (understanding, reasoning, judgment)

- Technical skills (specific ability to perform a job function well)

- Emotional intelligence (able to identify/manage their own emotions and recognize/influence the emotions of others)

Which bucket did most of the qualities fall into?

If you're like most people, most of the qualities landed in the emotional intelligence bucket. Great leaders have a sixth sense for people. They have a knack for saying the right thing at the right time. They know that support should sometimes be nurturing and other times be challenging. Above all, they know how to connect.

COMMUNICATION

You can make more friends in two months by becoming interested in other people than you can in two years by trying to get other people interested in you.

—Dale Carnegie

Genuine, honest dialogue is one of the most powerful relationship-building tools in existence. In Gary's case, he intuitively recognized that the best leaders create candor and build trust by seeking first to understand. He didn't try to convince anyone why he was right for the job. Instead, he started by getting others to open up. He asked them to share about the things that really mattered to them. He sought to pull out their insight and experience.

Gary knew that the best way to create value in conversation was to create depth. He did this through deep listening. He asked big, broad, meaningful open-ended questions. Then, he took in what people really felt and really thought.

This ability to inquire—to draw out what matters most to people—is the basis for being an expert communicator. It's also a powerful means to build relationships.

Only after Gary made others feel understood did he seek to share his point of view. This tactic is an essential key to increasing influence. After all, at that point in the conversation, Gary knew exactly what was most important to the person he was speaking to; they had just told him.

For example, after hearing a member share their desire to attract more socioeconomically diverse members, Gary responded by sharing an idea on how to offer more scholarships for leadership trainings. This naturally created common understanding.

Gary's ability to create commonality is what psychologists call the similarity attraction effect. This is the phenomenon in which people are attracted more strongly to others who are similar to them (“like attracts like”). Gary's skill at creating Shared Understanding took a solid connection and made it even stronger. Then he could build a platform for working together.

COLLABORATION

The fun for me in collaboration is, one, working with other people just makes you smarter; that's proven.

—Lin-Manuel Miranda

Gary wasn't interested in leading in a vacuum. He knew that to achieve success, it would take a team. He didn't just ask for votes; he asked for help. He asked others to join him on this mission of building the organization.

In making this request, Gary tapped into one of the strongest motivators of human behavior: the desire to be part of something that is greater than oneself. When you work toward a greater good, it brings a tremendous sense of purpose and meaning.

Moreover, when something really matters to you, you naturally bring more passion and energy to it. You also feel the satisfaction that comes from making progress toward a meaningful goal.

Gary created a vision in which people could already see themselves as part of the bigger picture. He got them excited about turning that vision into a reality. The next logical step was to act: to elect Gary so that they could get started making their vision come to life.

Finding ways to inspire and motivate those whom you lead brings your influence to a whole new level. When you harness the power of collaboration, you will achieve so much more than you could otherwise.

LOOKING IN THE MIRROR

You don't need to change the world; you need to change yourself.

—Miguel Ruiz

Ultimately, your leadership will be judged by your behavior: what you say and what you do. How you show up as a person is how you show up as a leader. You can't separate the two.

This idea isn't new. About 2,500 years ago, Socrates wrote, “To know thyself is the beginning of wisdom.” “Knowing thyself” has been rebranded as “self-awareness” in our present-day society.

Self-awareness is the foundation of emotional intelligence (EI). It's the basis of creating effective working relationships. After all, if you don't recognize your own drives and actions, how can you begin to understand the drives and actions of others?

Not only is EI essential to lead in today's organizations but also it's the competitive advantage of anyone who aspires to lead. In fact, when IQ and technical skills are roughly similar, EI accounts for nearly 90% of what moves people up the organizational ladder.1

Marshall Goldsmith, considered by many to be the world's preeminent executive coach, wrote a best-selling book called What Got You Here Won't Get You There. If leaders want to continue to develop, he argues, they must grow and change—and the first step of change is self-awareness. You need to hold up the mirror and pay attention. After all, you can't change what you don't see. Self-awareness is the skill that enables you to transform unconscious incompetence or competence into conscious competence. You can't become excellent at anything if you're oblivious as to why and how you do it.

Know thyself. It sounds so easy.

But it's easier said than done. Looking in the mirror is a lot harder than it seems. It takes humility to recognize that what's staring back at you is less than perfect.

We humans have a cognitive bias called illusory superiority. It's the reason that 90% of drivers think their driving skills are above average.2 It's common to overestimate our own abilities relative to others. Looking at our own flaws is hard. Some people find the process of self-examination so uncomfortable that they will repress, hide, or deny the facts. I certainly hid from the truth in the run-up to the election with Gary. However, as ostriches demonstrate so well, putting your head in the sand doesn't make reality go away.

If the idea of change makes you uncomfortable, you're on the right track. Leaders who are committed to developing themselves keep putting themselves in situations outside of their comfort zone. They know it's the only place they will grow.

FOCUS ON THE FUNDAMENTALS

Success is neither magical nor mysterious. Success is the natural consequence of consistently applying the basic fundamentals.

—Jim Rohn

When Gary shared his winning strategy with me, I was thunderstruck—and not just because it was a great strategy. I was astonished by how simple it was. Connection, communication, collaboration. In hindsight, it all just seemed obvious—common sense, even. So why hadn't I done something similar?

It's one thing to understand something conceptually. It's quite another to put it into practice. I thought I'd “got it.” But all I had gotten was the idea of leading. I hadn't followed through with action. I thought leading meant being all sophisticated. These basics? They were beneath me.

Yet, those fundamentals are the foundation for success. No, they don't require a great deal of sophistication. But they do require unusual amounts of focus, effort, and tenacity.

As an example, imagine that you're a star high school basketball player. In fact, you're so good that you're voted an All-American. Division 1 colleges fall all over themselves to give you a scholarship to their school. You could go anywhere you want.

You decide to go to UCLA. UCLA has built an amazing program and has won the last seven men's NCAA championships. No other school has won more than two in a row.

You're excited. It's now the first day of practice. You've come to play for Coach John Wooden, the winningest coach in basketball history. Coach Wooden is known as “The Wizard of Westwood.” What wisdom will he impart on the first day?

Coach Wooden begins the first lesson in the locker-room. He starts by telling you to take everything off of your feet. He then says,

The most important part of your equipment is your shoes and socks. You play on a hard floor. So you must have shoes that fit right. And you must not permit your socks to have wrinkles around the little toe—where you generally get blisters—or around the heels.3

You might think, “Has coach lost his mind? Doesn't he know I'm an All-American athlete? Is he for real?”

Coach Wooden doesn't stop there. He details how to put on your socks and shoes—holding the sock up while you put on the shoe, how to tie it and double-tie it. “I don't want shoes coming untied during practice or during the game,” he argues.4

What?!

You came all the way to UCLA to learn how to pull up your socks and tie your shoes!?

Coach Wooden then turns around and closes his practice by saying,

If there are wrinkles in your socks or your shoes aren't tied properly, you will develop blisters. With blisters, you'll miss practice. If you miss practice, you don't play. And if you don't play, we cannot win. If you want to win Championships, you must take care of the smallest of details.5

Coach Wooden was a master of the details. In fact, over his career, he developed a philosophy of coaching and leadership that he called the “Pyramid of Success.” Bigger things only came as a result of smaller things, and smaller things were based on fundamentals.

Whether it's basketball or leadership, success is based on fundamentals: learning them, mastering them, applying them, and teaching them to others.

These small details aren't hard to understand. The challenge is to consistently apply the fundamentals on a daily basis. That's what separates the amateurs from the pros and the average from the excellent.

Years ago, I had the opportunity to have dinner with a colleague and her father. Her father had started working more than 30 years before as a salesman for a food processing company, and, in the course of his career, he rose up the ranks and became CEO of what was a multibillion-dollar organization.

I asked him, “At what point in your career did you feel like you arrived? That you could relax and not work so hard to prove yourself? Was it when you became CEO?”

He beamed and broke into a hearty laugh. “Relax? Not prove myself? That's easy. I remember that day vividly. It was the day I retired.”

He continued, “When you lead, you keep coming back to the fundamentals: being a role model, communicating clearly, managing your time, providing vision, making informed decisions. That never ends. The day you stop doing that is the day you get into trouble.”

Connection, communication, and collaboration: you'll spot their fingerprints all over the handiwork of outstanding leaders. By the end of this book, you'll have a thorough understanding of these principles. You'll be armed with dozens of specific tools of how to apply them back at work. You'll be well equipped to make extraordinary leadership an everyday occurrence.

In doing so, you'll separate yourself from the pack. For as simple as the basics seem to be, they're not practiced consistently. These leadership fundamentals are sorely lacking in today's 21st-century organizations.

As we've already seen, most of today's leaders are mired in mediocrity. But it's not for lack of desire or effort. There are a lot of invisible forces working to get you stuck in a rut. The forces at play are much bigger than interactions at a personal level. As the acclaimed management consultant W. Edwards Deming stated, “A bad system will beat a good person every time.”6

These undercurrents are cultural, institutional, and societal in origin. They've been around for a long time and affect us in ways we don't even realize. It's important to know how these dynamics shape the way you see, think, and act as a leader. Understanding them enables you to step back and look at leadership through a long lens and see the big picture.

When you have this context, the basics will be illuminated with a rationale you wouldn't have otherwise. You'll see how what you do fits into the larger whole. Then, when you apply the basics, you won't be mindlessly following a leadership checklist that someone else wrote out for you. So, before diving deep into these three fundamental principles, let's look at these influences and how we got into this mess in the first place.