7 Strengthen the Story

In 1949, my father came to Liverpool

Seeking full employment on the Mersey docks

The war just four years over

And no work for him in Ireland

All he asked from England was a steady job

It’s true that there were jobs, but it was only daily labor

Some mornings he was hired for the working crew

Sometimes a week went by

With hands deep in empty pockets

Adversity and poverty were all he knew

So my father and his comrades

Set out to march to London

To ask the King for justice for the working class

To tell him those who’d fought the war

Had died for more than England

And with the peace should come a steady job at last

The day they started marching

I stood beside my father

I thought he was the bravest man I’d ever seen

He knelt down unexpectedly

And set me on his shoulder

And we marched off together to confront the King

I do not know how far it is from Liverpool to London

I don’t pretend that I recall each day and night

But when I close my eyes I can feel his face against me

As I rode into London on my father’s pride

These days when oh so many

Look for work on every corner

When justice seems so distant and the way so fraught

I recall us marching and from high up on his shoulder

I see the better world for which my father fought

We are carried on the shoulders

Of those who came before us

Such an over-used cliché

Such a tired, empty phrase

But my own father carried me

From Liverpool to London

On whose shoulders are we carried

In these troubling days

On whose shoulders are we carried

In these days

Sometimes when I talk about how, as creative community organizers, we need to make sure that culture is a central part of everything we do, what I get back is, “That’s easy for you to say. You’re a professional musician. What about those of us who were told in high school choir just to move our lips and never sing a note? What if we can’t even draw water out of a well?”

They often quote Emma Goldman: “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution.” (She didn’t say this, but everyone believes she did.) “But,” they continue, “she must have been a good dancer, or she’d never have said it. What if you’re a community organizer with two left feet (or, I guess, for fairness, two right feet)? Where does that leave you except sitting in the cultural-political wallflower seats at the back of the high school gym?”

They’ve got a point. But they’ve also got a problem. If people are going to organize themselves, take risks, confront power, they need to feel at least potentially powerful. One of the best ways organizers can support the people we work with, as they struggle to build up their self-confidence, is by helping them strengthen their stories.

The stories we tell ourselves and each other about where we came from, the work our families did, their values, what they believed, stood and fought for—these also shape our own sense of who we are, of what we can and should do. Woven together, strand across different strand, they become part of the fabric that holds campaigns and community organizations in place.

One of the most effective ways to create this community fabric is through the strategic use of culture in its many modes: music, art, poetry, theater, the multiple methods human beings use to tell stories. Knowing how to do this is an essential skill for organizers.

You’re right. That’s easy for me to say.

So here’s a suggestion. If you really are profoundly convinced that you have absolutely no musical or artistic talent, try applying a creative community organizing approach to the problem. Think about it as an organizational rather than a personal issue, and work to develop a collective rather than an individual strategy to resolve it.

That’s what we’ve done at Grassroots Leadership, where I’ve worked for the last thirty years. So let me use this organization as a practical case study in how to make culture central to creative community organizing.

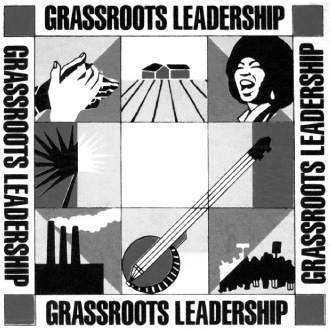

To start with, here is an old-fashioned visual:

We used this logo at Grassroots Leadership for many years— seven images set inside a traditional southern quilt pattern. Start with images of the economic reality that poor and working people confront: a factory with three smokestacks, pouring out smoke, perhaps about to close forever; a farm in distanced perspective, receding from view, much as family farms are disappearing all over the world. Go to the picture that depicts organizing for power, dark-skinned and light-skinned people together on a picket line. Observe the symbols of hope, of the future: a darker hand and a lighter hand either clasped or clapping; a stylized black and white palmetto, the state tree of South Carolina—or is it a rising sun?

Next notice the symbols of song and story. Folksinger/activist Pete Seeger’s five-string banjo stretches its long neck diagonally across the square. Gospel and freedom singer Jane Sapp, at that time a Grassroots Leadership board member, sings or shouts in the upper-right corner.

Go back to the hands. If clapping rather than clasped, are they keeping time with the rhythm of what Jane Sapp is singing? Is Jane one of the people on the picket line, leading the song or the chant, shouting out the demands? Are the hands those of the people on the picket line, keeping time to the song, the chant, the sound of their feet as they march?

These seven images, along with the quilt itself, embody the intersection of creative community organizing and cultural work that is Grassroots Leadership’s mission. They are also a fitting symbol of the way I’ve tried to work for the past forty-five years.

On the one hand, as a creative community organizer, my goal has been to help people who are marginalized, disenfranchised, and dispossessed build power for themselves and those like them, so that we can collectively achieve justice and equity for all.

On the other hand, I believe that power alone is not enough to win a just, equitable world. The experience of oppression does not necessarily make an individual, a community, or a nation wiser or more inherently democratic. When those who have been without power gain it, there is no guarantee they will exercise it more democratically than those who have had it before, or that their values related to race, gender, class, or sexual orientation, to take just these four examples, will be more enlightened, humane, or just.

Organizing alone, however creative, is rarely enough to change deeply held values and beliefs. To do that, we also need to use the cultural tools that throughout history have proved themselves able to break through to the human heart.

As organizers, we need to locate ourselves at that crossroads where activism and culture intersect, so that our work is rooted in both action and reflection. The dynamic tension between these varied ways of thinking and working will only give additional creativity and force to the work we do.

![]()

Organizing, in other words, must change more than power alone. It must also transform the relationship that the people being organized have to power. By integrating cultural work with traditional community organizing techniques, we can transform the nature of organizing and, through a process of celebration and community-building based in culture, art, and craft, help people change both their relationship to power, and how they think about and relate to themselves and to others.

People and their organizations may win on the issues. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they develop new understandings of how and why they won, of power and how it’s exercised, of difference and how it’s exploited. They may experience the power of numbers, but not necessarily the concurrent power of knowledge, of understanding. Some of the conditions of their lives may change, but they will not necessarily transform their relationship to others (particularly their relationships to others different from themselves, to the “other”), to themselves, to power.

These transformations lie within the realm and are the responsibility of political education. Yet traditional organizing by itself isn’t enough to create a transformative process that challenges anti-Semitism, racism, sexism, homophobia, and all the other barriers that divide people. Breaking through such rigid, resistant barriers requires velocity, momentum, torque, acceleration of the spirit as well as of the mind. It is a visceral and emotional as well as an intellectual process. Poems, songs, paintings, murals, chants, sermons, quilts, stories, rhythms, fabrics, pottery, dances can literally lift us out of ourselves, sometimes even into the life and consciousness of someone quite different from us.

The power of culture can also be an antidote to people’s prejudices, their inability to see beyond their own eyes. If creative community organizing can transform power, culture can transform consciousness, can perform the acts of political education that when combined with action make social change transformative rather than merely instrumental.

Yet within the world of traditional community organizing, culture is too often a matter of “add music and stir” (to paraphrase Charlotte Bunch’s famous quotation about women and history). Cultural workers and cultural work itself are often minor adjuncts to the organizing process: a quilt at an auction, a song at a rally, a chant on a picket line. Creative community organizing needs to draw on and incorporate the full power that culture can provide, the rich variety of traditional and nontraditional forms available to us: oral poetry, storytelling, midrash, meditation, quilting, guerrilla theater, preaching, drumming, unaccompanied song, silence.

Finding professional artists, making them allies, and learning to work with them in ways that bring not only their performing abilities but also their full artistic and political sensibilities into play should be a goal for all organizers and organizations. But it’s also critical (and this is something at which many cultural workers and political artists are highly skilled) to call forth and highlight the cultural skills of ordinary people, the members and leaders of our organizations.

A remarkable number of people who in no way consider themselves artists nonetheless paint, draw, sing, write, act, quilt, create pageants, preach, dance. Creating opportunities for them to do so as part of an ongoing campaign or organization allows them to voice their rage and hope, to move from being silenced to being outspoken, to strengthen the stories they tell themselves and others. If the worker who says no to the boss from the opposite side of the negotiating table finds power and pride in that act, so does the community person who reads her poetry at the mass meeting before the negotiations begin.

How do we as creative community organizers move towards effective integration of cultural work with everything else we do? One answer is to add a set of basic tools to our toolboxes. It may or may not be true that everyone is in some way an artist. But every organizer can learn a handful of basic cultural techniques to incorporate into their everyday work. The many options include helping community members and leaders write songs, poetry, and chants (one hint: do it collectively in small groups, rather than individually), and using storytelling and theater to create strategy.

Here’s one example of how to do this. It starts with a story, a piece of oral history told by Aunt Molly Jackson, radical midwife and union organizer from eastern Kentucky. I’ve memorized it, but it’s just as easy to read the script (available at www.sikahn.com). The story takes place in a Kentucky coal camp in the 1930s, where the miners have been locked out, and their children are starving. Aunt Molly borrows an empty sugar sack from a neighbor, robs the company store at gunpoint, distributes the food to the families who need it the most, and goes home:

My house was the next house

and by the time I got inside the door

the deputy sheriff was there to arrest me

And he said to me, he says,

Well, Aunt Molly, what in the world, he says

have you turned out, he says, to be a robber?

I said, Oh, no, Frank, I said

I am no robber

But, I said, it was the last chance

I have heard these little hungry children cry

for something to eat

‘til I’m desperate

I’m almost out of my mind

And, I said, I will get out

as I said

and collect that money

just as quick as I can

and pay them

I said, You know

I’m as honest

as the days is long

And the tears come in his eyes

And he said

Well, Aunt Molly, he says

They sent me up here, he says

to arrest you

The coal operator

well, Goodman, sent me here

to arrest you for that

But, he says

if you’ve got the heart

to do that much, he says

for other people’s children

that’s not got one drop

of your blood in their bodies, he says

then I will pay that bill myself, he says

and, he says, if they fire me

for not arresting you, he says

I will be damned glad of it

That’s just the way he said it

He walked out

and he didn’t arrest me

Aunt Molly’s story makes for a great follow-up discussion, in part because it creates an organizing “case study,” in which everyone shares the same experience and gets the same amount of information. I started using it when I was looking for a way to make training sessions seem more realistic, more like the actual situations organizers encounter in our work.

Discussions of potential strategies and tactics, I decided, could best be held in reference to an actual or constructed situation, when all persons participating had approximately the same degree of knowledge about what was going on. This information could be presented to the group by handing out a written document, showing a short film—or, it now occurred to me, using a narrative taken from oral history to approximate a real-life situation.

I begin this exercise by telling Aunt Molly Jackson’s “Hunger” story in her own words. I then work with the group to analyze the situation: strategy, tactics, leadership, communication, empowerment, risk. We talk through the complex strategic and ethical questions richly presented by the piece. Is Aunt Molly Jackson an organizer or a community leader? Does she make good strategic choices? Is she acting ethically when she points a gun at the store operator? Does she put people in the community at risk without their knowledge or approval? Is that something organizers sometimes just have to do—or is it never acceptable?

At a certain point, the participants begin demanding to know what actually happened, so they can compare their ideas to real life. Given that Aunt Molly’s story is about an incident that really did take place, that I’m a historian, and that from my days with the United Mine Workers of America I know many people who live and have lived, work and have worked in the coalfields, I could probably find out exactly what happened. But I decided it was better for the group—and for me—if I didn’t know the answer. Instead, I say, “Well, let’s find out,” and turn the discussion into improvisational theater.

Since I only know the story as Aunt Molly told it, I ask the participants to treat the story as a half-finished script and to act out the roles as a way of figuring out what might have happened. Members of the workshop became Daisy and Ann, the mothers of the starving children; Frank the good-hearted deputy sheriff; Frank’s boss, the “high sheriff”; Goodman the coal operator; Henry Jackson, Aunt Molly’s young son; Mr. Martin, the clerk at the company store; and Aunt Molly herself.

I act as the theater director to keep the action moving. I’ll say, for example, “All right, Frank, why don’t you go back to the jail now and explain to the sheriff why you decided to let Aunt Molly go free.” When (in our extension of the tale) the high sheriff cusses Frank out and strides off to the coal camp to arrest Aunt Molly himself, I’ll say, “Wow, it looks like Aunt Molly’s going to be in jail for a while. Maybe some of you folks whose children are still alive on account of what she did ought to have a meeting and decide what you’re going to do about that. Are you going to let her rot in jail after all she did for you?”

I never know how the scenario is going to play out. Sometimes Aunt Molly gets dragged off to jail after all, despite Frank’s attempt at intervention and rescue. Sometimes the women get themselves together, storm the jail waving broomsticks and banging on frying pans, and free her. Sometimes the sheriff fires on the crowd and someone gets killed.

Whatever happens, we talk about it, analyze, strategize. In a short time, we share an experience almost like organizing, made all the more real because it incorporates oral history, storytelling, and theater. The cultural content makes the theoretical discussion come alive, pulls it down out of thin air and nails it to the floor.

Sometimes the participants say, “But none of us know anything about coal mining or coal camps.” I try to get them to relate the situation to their own experience. “Okay,” I say, “let’s assume that instead of the high sheriff in the story we’re talking about the local police chief, and that Aunt Molly Jackson robbed the all-night convenience store on the corner next to the projects.” Once the story is reset locally, in terms of power dynamics that are already familiar, people usually overcome their resistance and jump back into the action.

Sometimes, I just plain get lucky. Once in Spokane, Washington, when someone said they didn’t understand what it meant to be in a coal camp, I asked if anyone in the group had ever lived in a company town. I got three hands: an African American woman who’d grown up in a coal camp in West Virginia; a Mexican American woman who’d been raised in a copper mining town in Arizona; and a European American man from a hard rock mining camp in northern Idaho. We were able to talk, not just about mines and company towns, but about class differences and commonalities across lines of gender and race.

I believe that integrating creative community organizing and cultural work is something any organization can do to some extent—and that the progressive movement would be both more effective and more fun if this happened. But at the same time, we need to recognize that this challenge makes demands on the organization that decides to take it on. Just as culture flourishes best in an open society (although extraordinary and heroic art has been created under the most repressive conditions), cultural work is most at home in a democratic organization.

So organizations must strive to provide a set of expectations and attitudes that are conducive to creativity, whether in organizing or in cultural work. We should be proud of our work, but we should always be learning to do it better. We need to be as open and analytical about our failures as we are celebratory about our successes.

Don’t be afraid to experiment. Within the world of community organizing, we need to extend our willingness to risk and fail. So don’t feel bad if you don’t have all the answers. I sure don’t, and I try hard not to pretend that I do.

Many people believe that what successful organizers have is good answers. That’s wrong. What we have is great questions. We’re not in a community to tell people what to do, but to ask them. One of the greatest skills an organizer can have is the ability to frame and ask questions in ways that make people not only want to answer them, but also to think deeply, and in unexpected ways, about what the answers might be.

This is how some of the best strategic research takes place, and how some of the most effective strategies and tactics are developed. Communities of all kinds have a sophisticated understanding of the problems they confront, and often solid, practical ideas about what can be done to solve these problems.

But no one person knows even a major part of the answer. Imagine a giant picture puzzle, with each person having some of the pieces. Not only are they not sure where those pieces go, they don’t even know how to start putting them together—and there’s no photograph on the box the puzzle came in to guide them.

That’s where the creative community organizer comes in: to help people work together to assemble the pieces, so that what they come up with makes at least reasonable sense to everyone who’s been part of the process—and so that they feel a sense of ownership over what they have created together. At its best, this is not just a political, but a cultural process.

As organizers, we need to be eternally vigilant about recognizing and confronting issues of race, class, gender, sexual orientation and power, and many other issues that can be used to dehumanize and divide people. We need to learn, however, not just how to talk about these principles, but how to incorporate them into the work that we do every day.

How then do we work with people, how do we reach and teach them, in ways that transform their understanding of power and their relationship to it, not just individually, but collectively? How do we help them strengthen the story they tell themselves and others, so that they have the self-confidence and pride to stand up and struggle for what they want and need?

Combining organizing with culture and cultural work is part of the answer. It is at this intersection that the future of creative community organizing, and of all work for social justice, lies. We are, as the great Mississippi Delta blues singer Robert Johnson sang so many years ago, “Standing at the crossroads, trying to flag a ride.”