As I hurtled through space, there was only one thought on my mind—that every part of the capsule was supplied by the lowest bidder.

—John Glenn

Firms entering new markets, particularly small- and medium-sized firms, often face problems in initial negotiations with importers, agents, and buyers in the target markets. These difficulties generally center on pricing questions, particularly the fact that their prices may be too high. Although price is only one of many issues that must be discussed during business negotiations, too frequently it tends to influence the entire negotiation process. New exporters may be inclined to compromise on price at the beginning of the discussions, thereby bypassing other negotiating strengths they may have, such as the product’s benefits, the firm’s business experience, and the firm’s commitment to providing quality products.

As pricing is often the most sensitive issue in business negotiations, it should be postponed until all of the other aspects of the transaction have been discussed and agreed upon.1 Decisions involving a long-term commitment to place export orders are, in any case, rarely made on the basis of price alone, but rather on the total export package. This is particularly so in markets where consumers are highly conscious of quality, style, and brand names, where marketing channels are well structured, and where introduction of the product in the market is time-consuming and expensive.

By presenting a more comprehensive negotiating package in a well-planned and organized manner, exporters should be able to improve the effectiveness of their negotiation discussions and, in the long term, the profitability of their export operations.

As a prelude to undertaking the negotiation, a negotiator should analyze his or her flexibility in negotiating on price. This requires examining the factors that influence the pricing decision.2 The factors to consider in international pricing exceed those in strictly domestic marketing not only in number, but also in ambiguity and risk. Domestic price is affected by such considerations as pricing objectives, cost, competition, customers, and regulations. Internationally, these considerations apply at home and in the host country. Further, multiple currencies, trade barriers, and longer distribution channels make the international pricing decision more difficult. Each of these considerations includes a number of components that vary in importance and interaction in different countries.

Pricing Objectives

Pricing objectives should be closely aligned to the marketing objectives. Essentially, objectives can be defined in terms of profit or volume. The profit objective takes the shape of a percentage markup on cost or price, or a target return on investment. The volume objective is usually specified as a desired percentage of growth in sales or as a percentage of the market share to be achieved.

Cost Analysis

Cost is one important factor in price determination. Of all the many cost concepts, fixed and variable costs are most relevant to setting prices. Fixed costs are those that do not vary with the scale of operations, such as number of units manufactured. Salaries of staff, office rent, and other office and factory overhead expenses are examples of fixed costs. On the other hand, variable costs, such as costs of material and labor used in the manufacture of a product, bear a direct relationship to the level of operations.

It is important to measure costs accurately in order to develop a cost/volume relationship and to allocate various costs as fixed or variable. Measurement of costs is far from easy. Some fixed, short-run costs are not necessarily fixed in the long run; therefore, the distinction between variable and fixed costs matters only in the short run. For example, in the short run, the salaries of salespeople would be considered fixed. However, in the long run, the sales staff could be increased or cut, making sales salaries a variable instead of a fixed expense.

Moreover, some costs that initially appear fixed are viewed as variable when properly evaluated. A company manufacturing different products can keep a complete record of a sales manager’s time spent on each product and, thus, may treat this salary as variable. However, the cost of that record keeping far exceeds the benefits derived from making the salary a variable cost. Also, no matter how well a company maintains its records, some variable costs cannot be allocated to a particular product.

The impact of costs on pricing strategy can be studied by considering the following three relationships: (1) the ratio of fixed costs to variable costs, (2) the economies of scale available to a firm, and (3) the cost structure of a firm with regard to competitors. If the fixed costs of a company in comparison with variable costs form the higher proportion of its total costs, adding sales volume will be a great help in increasing earnings. Such an industry would be termed volume-sensitive. In some industries, variable costs constitute the higher proportion of total costs. Such industries are price-sensitive, because even a small increase in price adds a lot to earnings.

If substantial economies of scale are obtainable through a company’s operations, market share should be expanded. In considering prices, the expected decline in costs should be duly taken into account; that is, prices may be lowered to gain higher market share in the long run. The concept of obtaining lower costs through economies of scale is often referred to as the experience effect, which means that all costs go down as accumulated experience increases. Thus, if a company acquires a higher market share, its costs will decline, enabling it to reduce prices. If a manufacturer is a low-cost producer, maintaining prices at competitive levels will result in additional profits. The additional profits can be used to promote the product aggressively and increase the overall scope of the business. If, however, the costs of a manufacturer are high compared to its competitors, prices cannot be lowered in order to increase market share. In a price-war situation, the high-cost producer is bound to lose.

The nature of competition in each country is another factor to consider in setting prices. The competition in an industry can be analyzed with reference to such factors as the number of firms in the industry, product differentiation, and ease of entry. Competition from domestic suppliers as well as other exporters should be analyzed.

Competitive information needed for pricing strategy includes published competitive price lists and advertising, competitive reaction to price moves in the past, timing of competitors’ price changes and initiating factors, information about competitors’ special campaigns, competitive product line comparison, assumptions about competitors’ pricing/marketing objectives, competitors’ reported financial performance, estimates of competitors’ costs (fixed and variable), expected pricing retaliation, analysis of competitors’ capacity to retaliate, financial viability of engaging in a price war, strategic posture of competitors, and overall competitive aggressiveness.

In an industry with only one firm, there is no competitive activity. The firm is free to set any price, subject to constraints imposed by law. Conversely, in an industry comprising a large number of active firms, competition is fierce. Fierce competition limits the discretion of a firm in setting price. Where there are a few firms manufacturing an undifferentiated product (such as in the steel industry), often only the industry leader has the discretion to change prices. Other industry members tend to follow the leader in setting price.

A firm with a large market share is in a position to initiate price changes without worrying about competitors’ reactions. Presumably, a competitor with a large market share has the lowest costs. The firm can, therefore, keep its prices low—thus discouraging other members of the industry from adding capacity—and further its cost advantage in a growing market.

When a firm operates in an industry that has opportunities for product differentiation, it can exert some control over pricing even if the firm is small and competitors are many. This latitude concerning price occurs when customers perceive one brand to be different from competing brands. Whether the difference is real or imaginary, customers do not object to paying a higher price for preferred brands. To establish product differentiation of a brand in the minds of consumers, companies spend heavily for promotion. Product differentiation, however, offers an opportunity to control prices only within a certain range.

Customer Perspective

Customer demand for a product is another key factor in price determination. Demand is based on a variety of considerations, price being just one. These considerations include the ability of customers to buy, their willingness to buy, the place of the product in the customer’s lifestyle (whether a status symbol or an often-used product), prices of substitute products, the potential market for the product (whether the market has an unfulfilled demand or is saturated), the nature of nonprice competition, consumer behavior in general, and consumer behavior in segments in the market. All of these factors are interdependent, and it may not be easy to understand their relationships accurately.

Demand analysis involves predicting the relationship between price level and demand, simultaneously considering the effects of other variables on demand. The relationship between price level and demand is called elasticity of demand, or sensitivity of price, and it refers to the number of units of a product that would be demanded at different prices. Price sensitivity should be considered at two different levels: the industry and the firm.

Industry demand for a product is elastic if demand can be substantially increased by lowering prices. When lowering price has little effect on demand, it is considered inelastic. Environmental factors, which vary from country to country, have a direct influence on demand elasticity. For example, in developed countries when gasoline prices are high, the average consumer seeks to conserve gasoline. When gasoline prices go down, people are willing to use gas more freely; thus, the demand for gasoline in developed countries can be considered somewhat elastic. In a developing country such as Bangladesh, where only a few rich people own cars, no matter how much gasoline prices change, total demand is not greatly affected, making demand inelastic.

When the total demand of an industry is highly elastic, the industry leader may take the initiative to lower prices. The loss in revenues from a decrease in price will presumably be more than compensated for by the additional demand generated, thus enlarging the total market. Such a strategy is highly attractive in an industry where economies of scale are possible. Where demand is inelastic and there are no conceivable substitutes, prices may be increased, at least in the short run. In the long run, however, the government may impose controls or substitutes may develop.

An individual firm’s demand is derived from the total industry demand. An individual firm seeks to find out how much market share it can command in the market by changing its own prices. In the case of undifferentiated, standardized products, lower prices should help a firm increase its market share as long as competitors do not retaliate by matching the firm’s price. Similarly, when business is sought through bidding, lower prices should help. In the case of differentiated products, however, market share can actually be improved by maintaining higher prices (within a certain range).

Products can be differentiated in various real and imagined ways. For example, a manufacturer in a foreign market who provides adequate warranties and after-sale service might maintain higher prices and still increase market share. Brand name, an image of sophistication, and the impression of high quality are other factors that can help differentiate a product and hence afford a company an opportunity to increase prices and not lose market share. In brief, a firm’s best opportunity lies in differentiating its product. A differentiated product offers more opportunity for increased earnings through premium prices.

Government and Pricing

Government rules and regulations pertaining to pricing should be taken into account when setting prices. Legal requirements of the host government and the home government must be satisfied. A host country’s laws concerning price setting can range from broad guidelines to detailed procedures for arriving at prices that amount to virtual control over prices.

Although international pricing decisions depend on various factors (such as pricing objective, cost competition, customer demand, and government requirements), in practice, total costs are the most important factor. Competitors’ pricing policies rank as the next important factor, followed by the company’s out-of-pocket costs, the company’s return-on-investment policy, and the customer’s ability to pay.

Aspects Of International Price Setting

The impact of such factors as differences in costs, demand conditions, competition, and government laws on international pricing is factored in by following a particular pricing orientation.3

Pricing Orientation

Companies mainly follow two different types of pricing orientation: the cost approach and the market approach. The cost approach involves computing all relevant costs and adding a desired profit markup to arrive at the price. The cost approach is popular because it is simple to comprehend and use, and it leads to fairly stable prices. It has two drawbacks though. First, definition and computation of cost can become troublesome. Should all (both fixed and variable) costs be included or only variable costs? Second, this approach brings an element of inflexibility into the pricing decision because of the emphasis on cost.

A conservative attitude favors using full costs as the basis of pricing. On the other hand, incremental-cost pricing would allow for seeking business otherwise lost. It means as long as variable costs are met, any additional business should be sought without any concern for fixed costs. Once fixed costs are recovered, they should not enter into the equation for pricing later orders.

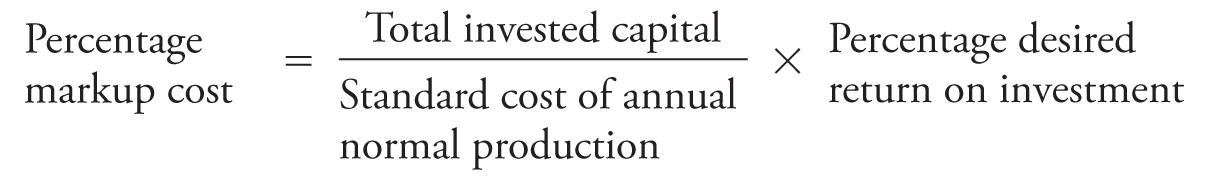

The profit markup applied to the cost to compute final price can simply be a markup percentage based on industry practice. Alternatively, the profit markup can represent a desired percentage return on investment.

This method is an improvement over the pure cost-plus-profit method because markup is derived more scientifically. Nonetheless, the determination of rate of return poses a problem.

Under the market approach, pricing starts in a reverse fashion. First, an estimate is made of the acceptable price in the target country segment. An analysis should be performed to determine if this price meets the company’s profit objective. If not, the alternatives are to give up the business or to increase the price. Additional adjustments in price may be required to cope with competitors, the host country government, an expected cost increase, and other eventualities. The final price is based on the market rather than estimated production costs.

Essentially, the cost and market approaches consider common factors in determining the final price. The difference between the two approaches involves the core concern in setting prices. The market approach focuses on pricing from the viewpoint of the customer. Unfortunately, in many countries, it may not be easy to develop an adequate price-demand relationship; therefore, implementation of the market approach can occur in a vacuum. It is this kind of uncertainty that forces companies to opt for the cost approach.

Export Pricing

Export pricing is affected by three factors:

1. The price destination (that is, who will pay the price—the final consumer, independent distributor, a wholly owned subsidiary, a joint venture organization, or someone else)

2. The nature of the product (that is, whether the product is a raw or semiprocessed material, components, or finished or largely finished products, or whether it is services or intangible property—patents, trademarks, formulas, and the like)

3. The currency used for billing (that is, the currency of the purchaser’s country, the currency of the seller’s home country, or a leading international currency)

The price destination is an important consideration since different destinations present different opportunities and problems. For example, pricing to sell to a government may require special procedures and concessions not necessary in pricing to other customers. A little extra margin might be called for. On the other hand, independent distributors with whom the company has a contractual marketing arrangement deserve a price break. Wholesalers and jobbers who shop around have an entirely different relationship with the exporter as compared to independent distributors.

As products, raw materials and commodities give a company very little leeway for maneuvering. Usually, a prevalent world price must be charged, particularly when the supply is plentiful. However, if the supply is short, a company may be able to demand a higher price.

Escalation of Export Prices

The retail price of exports is usually much higher than the domestic retail price for the same product. This escalation in foreign price can be explained by costs such as transportation, customs duty, and distributor margins—all associated with exports. The geographic distance the goods must travel results in additional transportation costs. Imported goods must also bear taxes in the form of customs duty imposed by the host government. In addition, completion of the export transaction can require passage of the goods through many more channels than in a domestic sale. Each channel member must be paid a margin for the service it provides, which naturally increases cost. Also, a variety of government requirements, domestic and foreign, must be fulfilled, resulting in further costs.

Export Price Quotation

An export price can be quoted to the overseas buyer in any one of several ways. Every alternative implies mutual commitment by the exporter and importer, and specifies the terms of trade. The price alters according to the degree of responsibility the exporter undertakes, which varies with each alternative.

There are five principal ways of quoting export prices: ex-factory; free alongside ship (FAS); free on board (FOB); cost, insurance, and freight (CIF); and delivered duty-paid. The ex-factory price represents the simplest arrangement. The importer is presumed to have bought the goods at the exporter’s factory. All costs and risks from thereon become the buyer’s problem.

The ex-factory arrangement limits the exporter’s risk. However, an importer may find an ex-factory deal highly demanding. From another country, a company could have difficulty arranging transportation and taking care of the various formalities associated with foreign trade. Only large companies or specialized trading firms can smoothly handle ex-factory purchases in another country.

The FAS contract requires the exporter to be responsible for the goods until they are placed alongside the ship. All charges incurred up to that point must be borne by the seller. The exporter’s side of the contract is completed upon receiving a receipt indicating safe delivery of goods and getting the goods through customs. Delivery and transfer of title take place at the side of the ship. The FAS price is slightly higher than the ex-factory price because the exporter undertakes to transport the goods to the point of shipment and becomes liable for the risk associated with the goods for a longer period.

The FOB price includes the actual placement of goods aboard the ship. The FOB price may be the FOB inland carrier or FOB foreign carrier. If it is an FOB inland carrier, the FOB price will be slightly less than the FAS price. However, if it is an FOB foreign carrier, the price will include the FAS price plus the cost of transportation to the importer’s country.

Under a CIF price quotation, the ownership of the goods passes to the importer as soon as they are loaded aboard the ship, but the exporter is liable for payment of freight and insurance charges up to the port of destination.

Finally, the delivered duty-paid alternative imposes on the exporter the complete responsibility for delivering the goods at a particular place in the importer’s country. Thus, the exporter makes arrangements for the receipt of the goods at the foreign port, pays necessary taxes/duties and handling, and provides for further inland transportation in the importer’s country. Needless to say, the price of delivered duty-paid goods is much higher than goods exported under the CIF contract.

Planning for Price Negotiation

To achieve a favorable outcome from a negotiation, an exporter should draw up a plan of action beforehand, which addresses a few key issues. Experienced negotiators know that as much as 80 percent of the time they devote to negotiations should go to such preparations. The preliminary work should be aimed at obtaining relevant information about the target market and the buyers of the product. Preparation should also include developing counterproposals in case objections are raised on any of the exporter’s opening negotiating points.4 So, the preparations should involve formulating the negotiating strategy and tactics.

Knowing what a buyer wants or needs requires advance research. In addition to customers’ preferences, an exporter should assess the competition from domestic and foreign suppliers and be familiar with the prices they quote. The exporter should also examine the distribution channels used for the product and the promotional tools and messages required. Such information will be valuable when negotiating with buyers. The more the exporter knows about the target market and the buyers for the products concerned, the better able he or she is to conduct the negotiations and match an offer to the buyer’s needs.5 On the other hand, making counterproposals requires that the buyer know detailed information about the costs of the exporter’s production operations, freight insurance, packaging, and other related expenses. An exporter should carry out a realistic assessment of the quantities his or her company can supply and schedule for supplying them. Every effort should be made to emphasize the export firm’s size, financial situation, production capacity, technical expertise, organizational strength, and export commitment with compatible buyers.

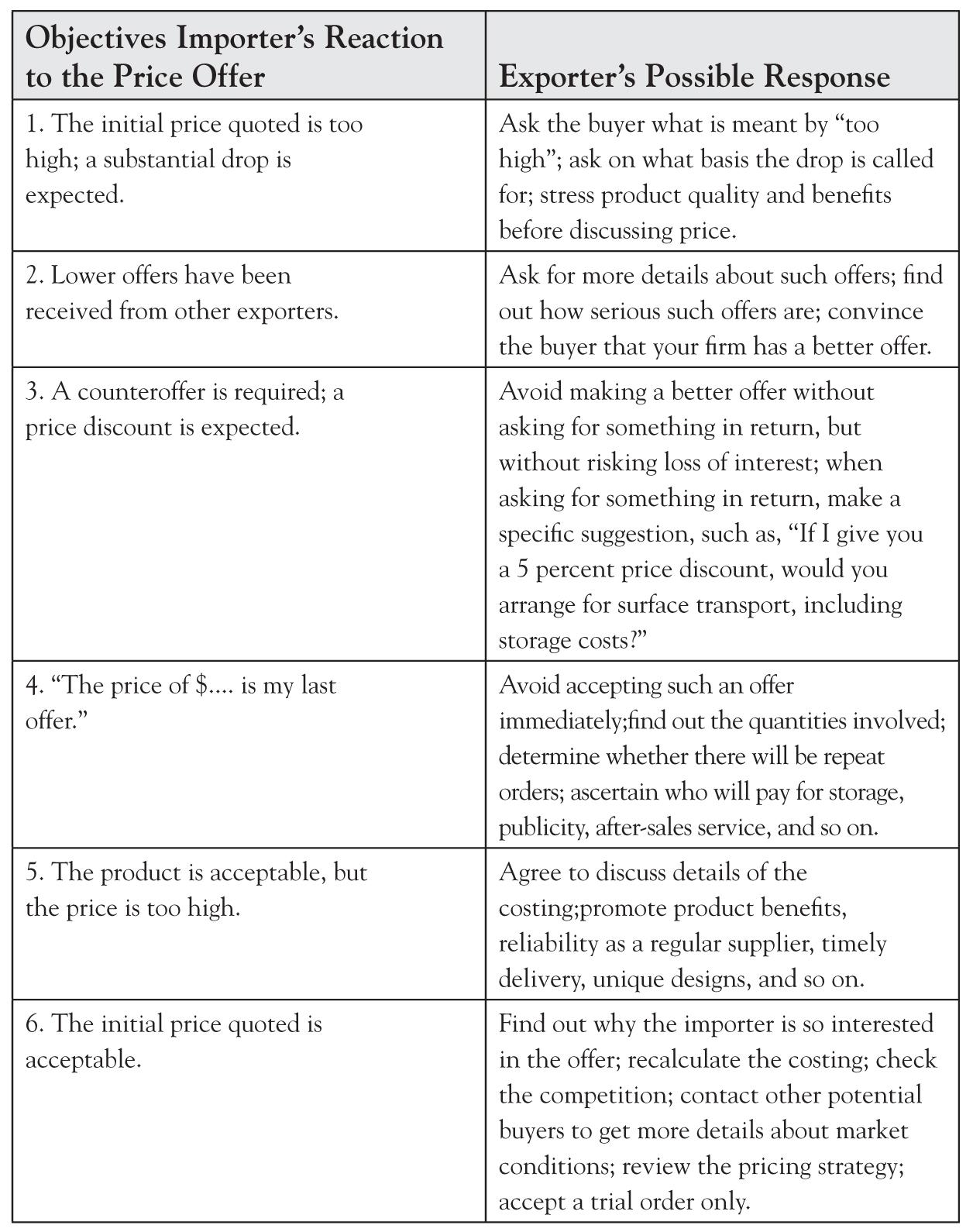

As part of the preparations for negotiations, the negotiator should list the potential price objections the buyer may have toward the offer along with possible responses. Some of the most common price objections, together with suggested actions, are listed in Figure 7.1. Sellers should adapt this list to their own product, the particular competitive situation, and specific market requirements.

Figure 7.1 Handling potential price objections

Source: Claude Cellich, “Negotiating Strategies: The Question of Price,” International Trade FORUM, April–June 1991, p. 12.

Into Negotiations

The preliminary groundwork should provide a negotiator with enough information to initiate the price negotiation. He or she should know the needs and requirements of the other party. If the subject of price is raised at the outset, the negotiator should avoid making any commitments or concessions at this point. The proceeding talks should include the following substantive topics.

Emphasize the Firm’s Attributes

A negotiator should promote the strength of his or her firm as a reliable commercial partner who is committed to a long-term business relationship. The other party should be convinced that the negotiator is capable of supplying the type of goods needed on acceptable terms. This can be accomplished by stressing the following aspects of a firm’s operations:

• Production capacity and processes, quality control system

• Technical cooperation, if any, with other foreign firms

• Export structure for handling orders

• Export experience, including types of companies dealt with

• Financial standing and references from banking institutions

• Membership in leading trade and industry associations, including chambers of commerce

• ISO certification

Highlight the Product’s Attributes

Once the other party is convinced he or she is dealing with a reliable firm, negotiations can be directed toward the product and its benefits. The attributes of a product tend to be seen differently by different customers. Therefore, a negotiator must determine whether his or her product fits the need of the other party.

In some cases, meeting the buyer’s requirements is a simple process. For example, during sales negotiations, a Thai exporter of cutlery was told by a U.S. importer that the price was too high, although the quality and finish of the items met market requirements. In the discussions, the exporter learned that the importer was interested in bulk purchases rather than prepackaged sets of 12 in expensive teak cases, as consumers in the United States purchase cutlery either as individual pieces or in sets of eight. The exporter then made a counterproposal for sales in bulk at a much lower price based on savings in packaging, transportation, and import duties. The offer was accepted by the importer, and both parties benefited from the transaction. This example illustrates that knowing what product characteristics the importer is looking for can be used to advantage by the exporter.

An exporter may not have a unique product, but by stressing the product attributes and other marketing factors in the negotiation, he or she can offer a unique package that meets the need of the importer.

Maintain Flexibility

In the negotiation process, the buyer may request modifications in the product and its presentation. The exporter should show a willingness to meet such a request if possible. The exporter should analyze whether the product adaptation would allow him or her to run a profitable export business. For example, in one case, negotiation on the export of teak coffee tables was deadlocked because of the high price of the tables. During the discussions, the exporter realized that the buyer was interested primarily in the fine finish of the tabletop. Therefore, the exporter made a counterproposal to supply the coffee table at a lower price, using the same teak top but with table legs and joineries made of less expensive wood. The importer accepted the offer, and the exporter was able to develop a profitable export business.

Offer a Price Package

After covering all of the nonprice issues, the exporter can shift the discussion in the final phase of the talks to financial matters that have a bearing on the price quotation. This is the time to come to an agreement on issues such as credit terms, payment schedules, currencies of payment, insurance, commission rates, warehousing costs, after-sales servicing responsibilities, costs of replacing damaged goods, and so on. Agreement reached on these points constitutes the price package. Any change in the buyer’s requirements after this agreement should be reflected in a new price package. For example, if the buyer likes the product but considers the final price to be too high, the exporter can make a counterproposal by, for example, cutting the price, but asking the buyer to assume the costs of transportation, to accept bulk packaging, and to make advanced payment.

Differentiate the Product

In some cases, price is an all-important factor in sales negotiation. The most obvious situation is when firms are operating in highly competitive markets with homogeneous products. Bypassing the pricing issue at the outset of negotiations is difficult when buyers are interested only in the best possible price, regardless of the source of supply. In such a situation, the negotiator should consider differentiating the product from those of the competition in order to shift the negotiations to other factors, such as product style, quality, and delivery.

Guidelines for Price Negotiations

An importer may reject an exporter’s price at the outset simply to get the upper hand from the beginning of the negotiation, thereby hoping to obtain maximum concessions on other matters. The importer may also object to the initial price quoted to test the seriousness of the offer, to find out how far the exporter is willing to lower the price, to seek a specific lower price because the product brand is unknown in the market, or to demonstrate a lack of interest in the transaction as the product does not meet market requirements.

If the importer does not accept the price, the exporter should react positively by initiating discussions on nonprice questions, instead of immediately offering price concessions or taking a defensive attitude. Widening the issues and exploring the real reasons behind the objections to the price quoted will put the talks on a more equal and constructive footing. Only by knowing the causes of disagreement can an exporter make a reasonable counteroffer. This counteroffer need not be based merely on pricing; it can also involve related subjects.

To meet price objections, some suppliers artificially inflate their initial price quotations. This enables them to give price concessions in the opening of the negotiation without taking any financial risk. The danger of this approach is that it immediately directs the discussion to pricing issues at the expense of other important components of the marketing mix. Generally, such initial price concessions are followed by more demands from the buyer that can further reduce the profitability of the export transaction. For instance, the buyer may press for concessions on the following:

• Quantity discounts

• Discounts for repeat orders

• Improved packaging and labeling (for the same price)

• Tighter delivery deadlines, which may increase production and transportation costs

• Free promotional materials in the language of the import market

• Free after-sales servicing

• Supply of free parts to replace those damaged from normal wear and tear

• Free training of staff in the maintenance and use of the equipment

• Market exclusivity

• A long-term agency agreement

• Higher commission rates

• Better credit and payment terms

To avoid being confronted by such costly demands, an exporter should from the outset try to determine the buyer’s real interest in the product. This can be ascertained by asking appropriate questions but must also be based on research and other preparations completed before the negotiations. Only then can a suitable counterproposal be presented.

Summary

Prices determine the total revenue and, to a large extent, the profitability of a business. When making pricing decisions, the following factors deserve consideration: pricing objective, cost, competition, customer, and government regulations. In price negotiations, these factors must be examined in reference to one’s own country and the other party’s country. Each factor is made up of a number of components that vary in each nation, both in importance and in interaction.

Price negotiations follow either a cost approach or a market approach. The cost approach involves computing all relevant costs and adding a profit markup to determine the price. The market approach examines price setting from the customer’s viewpoint. Export price negotiation is affected by three additional considerations: the price destination, the nature of the product, and the currency used in completing the transaction. Price escalation is an important consideration in export retail pricing. The retail price of exports usually is much higher than the domestic retail price for the same goods. This difference can be explained by the added costs associated with exports, such as transportation, customs duty, and distributor margin.

Satisfactory price negotiations require a negotiator to draw up a plan of action ahead of time with regard to buyer wants, willingness, and/or ability to pay, and objections likely to be raised on initially quoted price. The negotiator must prepare responses to the objections and decide whether he or she is willing to make a counterproposal on pricing.

While negotiating price objections likely to be raised on initially quoted price, the negotiator should emphasize his or her firm’s attributes, highlight his or her product’s attributes, maintain flexibility, offer a price package, and attempt to differentiate his or her products from those of the competition. In most negotiations, price is important; however, often at the time of closing, factors such as reliability, reputation, and financial stability are also taken into consideration.