Overview of Global Business Negotiations

In business you don’t get what you deserve, you get what you negotiate.

—Chester L. Karras

Business requires undertaking a variety of transactions. These transactions involve negotiations with one or more parties on their mutual roles and obligations. Thus, negotiation is defined as a process by which two or more parties reach agreement on matters of common interest. All negotiations involve parties (i.e., persons with common interests who deal with each other), issues (i.e., one or more matters to be resolved), alternatives (i.e., choices available to negotiators for each issue to be resolved), positions (i.e., defined response of the negotiator on a particular issue: what you want and why you want it), and interest (i.e., underlying needs a negotiator has). These should be identified and stated clearly at the outset.

In the post-World War II period, one of the most important developments has been the internationalization of business. Today companies of all sizes increasingly compete in global markets to seek growth and maintain their competitive edge. This forces managers to negotiate business deals in multicultural environments.

While negotiations are difficult in any business setting, they are especially so in global business because of (a) cultural differences between parties involved, (b) business environments in which parties operate differently, and (c) gender issues in global business negotiations. For these reasons, business negotiations across borders can be problematic and sometimes require an extraordinary effort.1 Proper training can go a long way in preparing managers for negotiations across national borders. This book provides know-how and expertise for deal making in multicultural environments.

The book is meant for those individuals who must negotiate deals, resolve disputes, or make decisions outside their home markets. Often managers take international negotiations for granted. They assume that if correct policies are followed, negotiations can be carried out without any problems. Experience shows, however, that negotiations across national boundaries are difficult and involve a painstaking process. Even with favorable policies and institutions, negotiations in a foreign environment may fail because individuals are dealing with people from a different cultural background within the context of a different legal system and different business practices. When negotiators have the same nationality, their dealing takes place within the same cultural and institutional setup. But where negotiators belong to different cultures, they have different approaches and assumptions relative to social interactions, economic interests, legal requirements, and political realities.

This book provides business executives, lawyers, government officials, and students of international business with practical insights into international business negotiations. For those who have no previous training in negotiations, the book introduces them to the fundamental concepts of global deal making. For those with formal training in negotiation, this book builds on what they already know about negotiation in the global environment.

Negotiation is interdependent, since what one person does affect another party. It is imperative, therefore, that a negotiator, in addition to perfecting his or her own negotiating skills, focus on how to interact, persuade, and communicate with the other party. A successful negotiator works with others to achieve his or her own objectives. Some people negotiate well, while others do not. Successful negotiators are not born; rather, they have taken the pains to develop negotiating skills through training and experience.

Negotiation Architecture

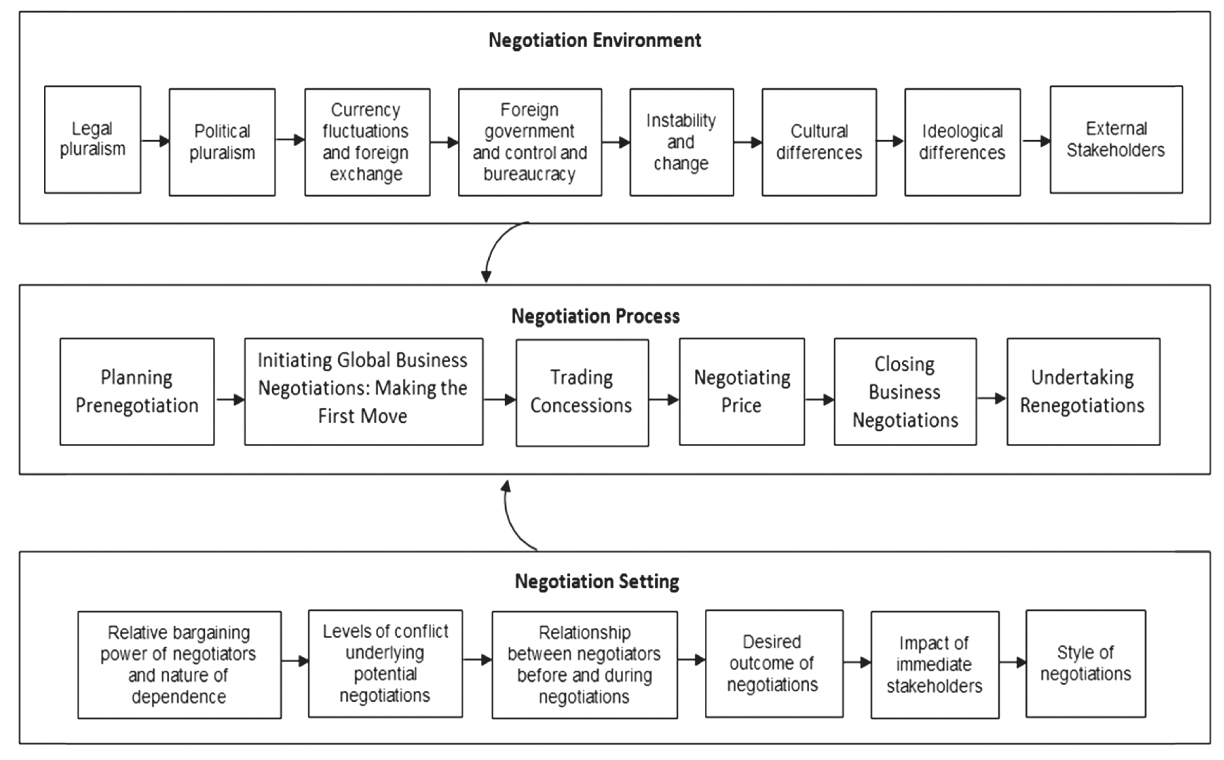

There are three aspects to the architecture of global negotiations: negotiation environment, negotiation setting, and negotiation process. Negotiation environment refers to the business climate that surrounds the negotiations; this is beyond the control of negotiators. Usually, negotiators have influence and some measure of control over the negotiation setting. Negotiating process refers to the events and interactions that take place between parties to reach an agreement. Included in the process are the verbal and nonverbal communication among parties, the display of bargaining strategies, and the endeavors to strike a deal. Figure 1.1 depicts the three aspects of negotiation architecture.

Figure 1.1 Negotiation architecture

Negotiation Environment

Negotiation environment can be thought of having the following components: legal pluralism, political pluralism, currency fluctuations and foreign exchange, foreign government control and bureaucracy, instability and change, cultural differences, ideological differences, and external stakeholders.2

Legal Pluralism A multinational enterprise in its global negotiations must cope with widely different laws. A U.S. corporation not only must consider U.S. laws wherever it negotiates, but also must be responsive to the laws of the negotiating partner’s country. For example, without requiring proof that certain market practices have adversely affected competition, U.S. law, nevertheless, makes them violations. These practices include horizontal price fixing among competitors, market division by agreement among competitors, and price discrimination. Even though such practices might be common in a foreign country, U.S. corporations cannot engage in them. Simultaneously, local laws must be adhered to even if they forbid practices that are allowed in the United States. For example, in Europe, a clear-cut distinction is made between agencies and distributorships. Agents are deemed auxiliaries of their principal; distributorships are independent enterprises. Exclusive distributorships are considered restrictive in European Union (EU) countries. The foreign marketer must be careful in making distribution negotiations in, say, France, so as not to violate the regulation concerning distributorship contracts.

Negotiators should be fully briefed about relevant legal aspects of the countries involved before coming to agreement. This will ensure that the final agreement does not contain any provision that cannot be implemented because it is legally prohibited. The best source for such briefings is a law firm with in-house expertise on legal matters of the counterpart’s country.

Political Pluralism A thorough review of the political environment of the party’s country with whom negotiation is planned must precede the negotiation process. An agreement may be negotiated that is legal in the countries involved and yet may not be politically prudent to implement. There is no reason to spend effort in negotiating such a deal. Consider the following example.

The U.S. federal government officially discourages cigarette smoking in the United States. But if people in other countries are going to smoke, why shouldn’t they puff away on American tobacco?

Thailand, with a government tobacco monopoly of its own, has been fighting U.S. pressure to open up, and U.S. tobacco companies approached the Bush administration to take up trade sanctions against Thai authorities. That raises the question about U.S. trade policy, such as: Should Washington use its muscle to promote a product overseas that it acknowledges is deadly? The U.S. should first examine this question before deciding to negotiate with the Thai authorities to open their cigarette market.3

A thorough review of the political environment of a country must precede the negotiation exercise. A rich foreign market may not warrant entry if the political environment is characterized by instability and uncertainty.

Political perspectives of a country can be analyzed in three ways: (1) by visiting the country and meeting credible people; (2) by hiring a consultant to prepare a report on the country; and (3) by examining political risk analysis worked out by such firms as the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), a New York-based subsidiary of the Economist Group, London, or the Bank of America’s country Risk Monitor or BERI S.A.’s Business Risk Service.

Currency Fluctuations and Foreign Exchange A global negotiation may involve financial transfers across national lines in order to close deals. Financial transfers from one country to another are made through the medium of foreign exchange. Foreign exchange is the monetary mechanism by which transactions involving two or more currencies take place. It is the exchange of one country’s money for another country’s money.

Transacting foreign exchange deals presents two problems. First, each country has its own methods and procedures for effecting foreign exchanges—usually developed by its central bank. The transactions themselves, however, take place through the banking system. Thus, the methods of foreign exchange and the procedures of the central bank and commercial banking constraints must be thoroughly understood and followed to complete a foreign exchange transaction.

A second problem involves the fluctuation of rates of exchange that occurs in response to changes in supply and demand of different currencies. For example, in 1992, a U.S. dollar could be exchanged for about three Swiss francs. In early 2001, this rate of exchange went down to as low as 1.3 Swiss francs for a U.S. dollar, and in early 2016 the U.S. dollar further declined such that a dollar fetched less than one Swiss franc. Thus, a U.S. businessperson interested in Swiss currency must pay much more today than in the 1990s. In fact, the rate of exchange between two countries can fluctuate from day to day. This produces a great deal of uncertainty, as a businessperson cannot know the exact value of foreign obligations and claims.

Foreign Government Controls and Bureaucracy An interesting development of the post-World War II period has been the increased presence of government in a wide spectrum of social and economic affairs it previously ignored. In the United States, concern for the poor, aged, and minorities, as well as consumers’ rights and the environment has spurred government response and the adoption of a variety of legislative measures. In a great many foreign countries, such concerns have led governments to take over businesses to be run as public enterprises. Sympathies for public-sector enterprises, successful or not as businesses, have rendered private corporations suspect and undesirable in many countries. Also, public-sector enterprises are not limited to developing countries. Great Britain and France had many government corporations, from airlines, to broadcasting companies, to banks and steel mills. Thus, in many nations, negotiations may take place with a government-owned company, where profit motive may not be as relevant as for a private company.

Some nations look upon foreign investment with suspicion. This is true of developed and developing countries. Take, for example, Japan, where it is extremely difficult for a foreign business to establish itself without first generating a trusting relationship that enables it to gain entry through a joint venture. Developing countries are usually afraid of domination and exploitation by foreign businesses. In response to national attitudes, these nations legislate a variety of controls to prescribe the role of foreign investment in their economies. Therefore, a company should review a host country’s regulations and identify underlying attitudes and motivations before deciding to negotiate there. For advice on legal matters, the company should contact a law firm, who may know an expert in the host country. Furthermore, the company should examine the political risk analysis of firms such as the Economist Intelligence Unit, mentioned previously.

The government of a country sometimes imposes market control to prevent foreign companies from competing in certain markets. For example, until recently, Japan prohibited foreign companies from selling sophisticated communications equipment to the Japanese government. Thus, AT&T, Hewlett Packard, and Cisco could do little business with Japan.

Obviously, in nations with an ongoing bias against homegrown private businesses, a foreign company cannot expect a cordial welcome. In such a situation, the foreign company must contend with the problems that arise because it is a private business as well as a foreign one. Sound business intelligence and familiarity with the industrial policy of the government and related legislative acts and decrees should provide clarification of the role of the private sector in any given economy. This type of information should be fully absorbed before proceeding to negotiate.

Instability and Change Many countries have frequent changes of government. In such a climate, a foreign business may find that by the time it is ready to implement an agreement, the government with whom the initial agreement was negotiated has changed to one that is not sympathetic to the commitment by its predecessor. Consequently, it is important for international negotiators to examine, before making agreements, whether the current government is likely to continue to be in office for a while. In a democratic situation, the incumbent party’s strength or the alternative outcomes of the next election can be weighted to assess the likelihood of change. To learn about the political stability of a country, a company should contact someone who has been doing business in the host country for some time. A company may also gain useful insights on this matter from its government agencies. For example, in the U.S., a company may contact the International Trade Administration (U.S. Department of Commerce) in its area for advice; they may even put the company in touch with a representative in the host country.

More than anything else, foreign companies dislike frequent policy changes by host countries. Policy changes may occur even without a change in government. It is important, therefore, for foreign businesses to analyze the mechanism of government policy changes. Information on the autonomy of legislatures and study of the procedures followed for seeking constitutional changes can be crucial for the global negotiator.

An example of policy change is provided by China. A few years ago, China ordered all direct-sales operations to cease immediately. Alarmed by a rise in pyramid schemes by some direct sellers and uneasy about big sales meetings held by direct sellers, Beijing gave all companies that held direct-selling licensing six months to convert to retail outlets or shut down altogether. The move threatened Avon’s China sales, of about $75 million a year, and put Avon, Amway, and Mary Kay Inc.’s combined China investment of roughly $180 million at risk. It also created problems for Sara Lee Corporation and Tupperware Corporation, which had recently launched direct-sales efforts in China.4 (China withdrew the order after a little arm-twisting from Washington and because over 20 million Chinese were involved in direct sales, with more turning to the businesses as unemployment rose.)

Sovereign nations like to assert their authority over foreign business through various sanctions. Such sanctions are regular and evolutionary and, therefore, predictable. An example is increase in taxes over foreign operations. Many developing countries impose restrictions on foreign business to protect their independence. (Economic domination is often perceived as leading to political subservience.) These countries are protective of their political freedom and want to maintain it at all costs, even when it means proceeding at a slow economic pace and without the help of foreign business. Thus, the problem posed by political sovereignty exists mainly in developing countries.

The industrialized nations, whose political sovereignty has been secure for a long time, require a more open policy for the economic realities of today’s world. Today, governments are expected simultaneously to curb unemployment, limit inflation, redistribute income, build up backward regions, deliver health services, and avoid abusing the environment. These wide-ranging objectives make developing countries seek foreign technology, use foreign capital and foreign raw materials, and sell their specialties in foreign markets. The net result is that these countries have found themselves exchanging guarantees for mutual access to one another’s economies. In brief, among developed countries, multi-nationalism of business is politically acceptable and economically desirable, which is not always true of developing countries.

A basic management reality in today’s economic world is that businesses operate in a highly interdependent global economy and that the 200-plus developing countries are significant factors in the international business area. They are the buyers, suppliers, competitors, and capital users. To successfully negotiate in developing countries, a company must recognize the magnitude and significance of these roles.

Cultural Differences Doing business across national boundaries requires interaction with people nurtured in different cultural environments. Values that are important to one group of people may mean little to another. Some typical attitudes and perceptions of one nation may be strikingly different from those of other countries. These cultural differences deeply affect negotiation behavior. International negotiators, therefore, need to be familiar with the cultural traits of the country with which they want to negotiate. International business literature is full of instances where stereotyped notions of countries’ cultures have led to insurmountable problems.

The effect of culture on international business ventures is multifaceted.5 The factoring of cultural differences into the negotiating process to enhance the likelihood of success has long been a critical issue in overseas operations. With the globalization of commerce, cultural forces have taken on additional importance. Naivety and blundering in regard to culture can lead to expensive mistakes. And although some cultural differences are instantly obvious, others are subtle and can surface in surprising ways.6

Successful negotiators advise that in Asian cultures, a low-key, nonadversarial, win-win negotiating style works better than a cut-and-dried businesslike attitude. A negotiator should listen closely, focus on mutual interests rather than minor differences, and nurture long-term relationships.

Four aspects of culture are especially important in negotiating well. They are spoken language, body language, attitude toward time, and attitude toward contracts.7

Ideological Differences There are always ideological differences between nations, which influence the behaviors of their citizens. Ideologies that are attributed to traditional societies imply that they are compulsory in their force, sacred in their tone, and stable in their timeliness. They call for fatalistic acceptance of the world as it is, respect for those in authority, and submergence of the individual in collectivity. In contrast to this, the ideologies of Western societies can be described as stressing acquisitive activities, an aggressive attitude toward economic and social change, and a clear trend toward a higher degree of industrialization.

For example, many feel that having a contract with the Chinese does not have the same meaning because Chinese do not view contracts as binding. Even if a contract was negotiated in good faith with Mr. Chu, when Mr. Lin comes in to replace Mr. Chu, he might say, “Well, you signed the contract with Mr. Chu, not me. So to me this contract is void. So what you can do is to sue the Chinese government.” While keeping their ideological differences intact, traditional societies want to be economically absorbed in Western ways, having a strong emphasis on specificity, universalism, and achievement. Thus, if matters are handled in a delicate fashion, problems can be averted.

Negotiators should be familiar with and respect each other’s values and ideologies. For example, a fatalistic belief may lead an Asian negotiator to choose an auspicious time to meet the other party. The other party should be duly sensitive to accommodate the ideological demands of his or her counterpart.

External Stakeholders The term external stakeholders refers to different people and organizations that have a stake in the outcome of a negotiation. These can be stockholders, employees, customers, labor unions, business groups (e.g., chambers of commerce), industry associations, competitors, and others. Stockholders welcome the negotiation agreement when it increases the financial performance of the company. Employees support the negotiation that results in improved gains (financial and in-kind) for them. Customers favor the negotiation that enables them to have quality products at a lower price. Thus, if a foreign company that is likely to provide good value to consumers is negotiating to enter a country, the consumers will be excited about it. However, the industry groups will oppose such negotiation to discourage competition from the foreign company.

Different stakeholders have different agendas. They support or oppose negotiation with a foreign enterprise depending on how it will affect them. In conducting negotiation, therefore, a company must examine the likely reaction of different stakeholders.

Negotiation Setting

Negotiation setting refers to factors that surround the negotiation process and over which the negotiators have some control. The following are the dimensions of negotiation setting: the relative bargaining power of the negotiators and the nature of their dependence on each other, the levels of conflict underlying potential negotiation, the relationship between negotiators before and during negotiations, the desired outcome of negotiations, impact of immediate stakeholders, and style of negotiations.

Relative Bargaining Power of Negotiators and Nature of Dependence

An important requisite of successful negotiations is the mutual dependence of the parties on one another. Without such interdependence, negotiations do not take place. The degree of dependence determines the relative bargaining power of each side. The style and strategies adopted by a negotiator depend on his or her bargaining power. A company with greater bargaining power is likely to be more aggressive than one with weaker bargaining power. A company with other equally attractive alternatives may apply a “take it or leave it” posture, while a company with no other choice to fall back upon may adopt a more submissive stance.

Levels of Conflict Underlying Potential Negotiations Every negotiation situation has a few key points. When both parties agree on essential issues, the negotiation is concluded with supportive attitude. On the other hand, differences over the key points may cause the potential negotiation to conclude in a hostile environment.

Where the goals of two parties depend on each other in such a way that the gains of one party have a positive impact on the gains of the other party, the negotiations are concluded in a win-win situation (also called a nonzero-sum game, or integrative bargaining). If, however, the negotiation involves a win-lose situation (i.e., the gains of one side result in losses for the other party), the negotiation will proceed in a hostile setting.

Suppose a U.S. women’s fashion company is interested in manufacturing some of its goods in a developing country to take advantage of low wages. The developing country, on the other hand, is interested in increasing employment. This presents a win-win situation, and the negotiation will take place in a friendly setting. Assume a European company is negotiating a joint venture in a developing country. The company desires majority equity control in the joint venture, while the government of the developing country is opposed to it (i.e., the government wants the foreign company to have a minority interest in the joint venture). This case represents a win-lose situation (or a zero-sum game, or distributive bargaining) since the gains of one party come at the cost of the other.

Relationship between Negotiators before and during Negotiations The history of a positive working relationship between negotiating parties influences future negotiations. When previous negotiations establish a win–win situation, both sides undertake current negotiation with a positive attitude, hoping to negotiate another win-win agreement. However, when the previous experience is disappointing, the current negotiation setting may begin with a pessimistic attitude.

Even during the current negotiation, what happens in the first session sets the stage for the next session and so on. Usually, a negotiation involves several sessions over a period of time. When, in the first session, relationships are less than cordial, future sessions may proceed in a negative atmosphere. Therefore, a company should adopt a positive, friendly, and supportive posture in the initial session(s). Every effort should be made to avoid conflicting issues.

Desired Outcome of Negotiations The outcomes of global business negotiation can be tangible and intangible. Examples of tangible outcomes are profit sharing, technology transfer, royalty sales, protection of intellectual property, equity ownership, and other outcomes whose values can be measured in concrete terms. Intangible outcomes include the goodwill generated between two sides in a negotiation, the willingness to offer concessions to enhance the relationship between parties (and the outcome through understanding), and give-and-take. The tangible-intangible outcomes can be realized in the short term or long term.

One basic precept of global business negotiation is to compromise for tangible results to happen in the long run. Business deals are long-term phenomena. Even when a company is interested in negotiating with a foreign company only for an ad hoc deal, the importance of a long-term relationship and its positive impact should be remembered. The situation may change in the future such that the company with whom a person negotiated in the past on a minor project may not be a major player for which he or she is currently negotiating. Relationship is an important criterion for conducting successful negotiations. And it takes time to establish a relationship.

Often, developing countries want multinational companies to transfer technology to the country. But technology is a very important and unique asset of the company, which it does not want to fall into the wrong hands. Negotiators from developing countries should, in the short term, be willing to live with intangible benefits from the current negotiation, in the interest of realizing the tangible gain of technology transfer in the long run. Similarly, a multinational corporation might initially accept a minority position in a developing country if the latter is willing to reconsider the equity ownership question a few years later. When goodwill is created, the government may approach the company’s desire to have equity control in the venture with an open mind.

Impact of Immediate Stakeholders The immediate stakeholders in global business negotiation refer to employees, managers, and members of the board of directors. Their experience in global negotiations, their cultural perspectives, and their individual stakes in negotiation outcomes have a bearing on the negotiating process.

Long-term experience in negotiating deals with Japanese, for example, teaches a U.S. manager that the Japanese do not mean yes when they say “okay” to some point. Experience also teaches about the rituals of a culture and the meaning of gestures, jokes, gifts, and so on. Such experience comes in handy in the planning of negotiating tactics and strategies. Likewise, the cultural background of negotiators influences the outcomes. In Russia and Eastern European countries, the emphasis on profits by Western managers is not easy to grasp. In many cultures, people like to deal with their equals. Thus, a lower-ranking Western manager may have a problem negotiating with the CEO of an Indian company. The ranks of the people involved in negotiation are a consideration in the successful outcome. Other cultural traits such as outside interests, emphasis on time, etc. also impact negotiations.

Different stakeholders have different stakes in the negotiation. Labor in a developed country does not want global negotiation to transfer jobs overseas or to use pressure to institute lower wages. Managers do not like to negotiate an agreement that counters their personal stakes, such as financial gain, career advancement, ego, prestige, personal power, and economic security. Members of a board of directors may be interested in an agreement for prestige sake rather than any financial gain. This means they might compromise on an agreement in terms of profit as long as it ensures the prestige they are seeking.

Style of Negotiations Every person has certain traits that characterize his or her way of undertaking negotiation. Some people adopt an aggressive posture and hope to get what they want by making others afraid of them. Some people are low-key and avoid confrontation, hoping their counterparts in negotiations are rational and friendly. Different styles have their merits and demerits.

With regard to negotiations, the best style is the one that satisfies the needs of both parties. In other words, a negotiator should embrace a style that helps in a win-win outcome, i.e., adopt a style that makes the other party feel comfortable and helps in minimizing any conflict.

Negotiation Process

Although companies of all sizes run into negotiation problems, managers of small- and medium-sized firms often lack the business negotiation skills needed to make deals in the international marketplace. These companies may also need negotiation skills for discussions with importers or agents when the firm is exporting its products. Such skills are also necessary when the firm is exploring joint-venture possibilities abroad or purchasing raw materials from foreign suppliers. As mentioned previously, negotiating with business partners located in other countries, where the customs and language of the counterpart are different from those at home, is more difficult than dealing with local companies. Such cultural factors add to the complexities of the transaction.

Assume the export manager of a small manufacturing company specializing in wooden kitchen cabinets wants to find an agent for the firm’s products in a selected target market and has scheduled a visit there for this purpose. The manager has never been to the country and is not familiar with the business practices or the cultural aspects. The manager realizes the need for a better understanding of how to conduct business negotiations in the market before meeting several potential agents.

The negotiation process introduced in this book (see Figure 1.1) can be of real help to managers who do not have any formal training on the subject. The negotiation begins with prenegotiation planning and ends with renegotiation, if necessary. In between are stages of initiating negotiation, trading concessions, negotiating price, and closing the deal.

After completing prenegotiation planning, negotiation begins with contention; i.e., each party starts from a different point concerning what he or she hopes to achieve through negotiation. In the example above, when the export manager meets the potential agents in the target market, he or she has certain interests to pursue in the business dealings that may not necessarily coincide with those of the counterpart. The manager may want the agent to work for only a minimal commission so the extra profits can be reinvested in the company to expand and modernize production. Furthermore, the manager may wish to sign up several other agents in the same country to increase the possibility of export sales; he or she may also want to limit the agency agreement to a short period in order to test the market. The potential agent, on the other hand, may demand a higher percentage of sales than is being offered as commission, may insist on exclusivity within the country concerned, and may call for a contract of several years instead of a short trial period. In this situation, the exporter needs to know how to proceed in the talks to ensure that most of the firm’s interests are covered in the final agreement.

The terms clarification, comprehension, credibility, and creating value are basic phrases in the negotiating process between the initial starting position and the point where both parties develop a common perspective. By applying each concept in sequence, one can follow a logical progression during the negotiation.

Clarification and comprehension are the first steps away from the situation of confrontation. In the case above, the exporter and the potential agent should clarify their views and seek the understanding of the other party about matters of particular concern. For instance, the parties may learn that it is important for the exporter to obtain a low commission rate and for the agent to have exclusivity in the territory concerned.

The next stages in business negotiation concern the concepts of credibility and creating value; i.e., the attitudes that develop as both parties discuss their requirements and the reasons behind them. In the example above, this may mean that the agent accepts as credible the exporter’s need to reinvest a large portion of profits in order to keep the company competitive. The exporter, on the other side, has confidence that the agent will put maximum efforts into promoting the product, thus assuring the exporter that a long-term contract is not disadvantageous. As the negotiation proceeds, the two gradually reach a convergence of views on a number of points under discussion.

Following this is the stage of concession, counterproposals, and commitment. In this phase, the final matters on which the two parties have not already agreed are settled through compromises on both sides.

The final stage is conclusion; that is, agreement between the two parties. In the case of the exporter, this means a signed agreement with a new agent, incorporating at least some of the exporter’s primary concerns (such as a low commission on sales) and some of the agent’s main considerations (for instance, a two-year contract). The negotiation process, however, is not complete as circumstances may change, particularly during the implementation phase, requiring a renegotiation, a possibility both parties should keep in mind.

Negotiation Infrastructure

Before proceeding to negotiate, it is desirable to put negotiation infrastructure in place. It makes the lives of negotiators easier and makes their jobs more rewarding. The infrastructure consists of assessing the current status of the company and establishing the BATNA; i.e., best alternative to a negotiated agreement.

Assessing Current Status

The current status can be assessed using the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis, a technique often used to assess business management situations. Although this is a well-known business management tool, insufficient attention has been given to linking the results of a SWOT analysis with the development of a business negotiation strategy.

The SWOT method as used for business management purposes consists, in simple terms, of looking at a firm’s production and marketing goals and assessing the company’s operations and management policies and practices in the light of these goals. The framework for this analysis consists of four key words: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. All aspects of the company’s activities are reviewed and classified under one of these terms.

This analysis is taken a step further when the results of SWOT analysis are applied to a negotiating plan. The strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats identified are used to plan the negotiating strategy and tactics. Applying the SWOT technique to cross-border negotiations helps executives optimize their companies’ strengths, minimize their weaknesses, be open to opportunities, and be ready to neutralize threats. On the basis of his or her company’s strengths, a negotiator can obtain more support for the firm’s proposals during the discussions. Similarly, to offset weaknesses, the negotiator can minimize their importance by focusing on other aspects of the talks or broadening the range of issues. With regard to opportunities, specific plans can be incorporated into the negotiating strategy for capitalizing on them. Finally, any threats to the company’s business operations identified through the SWOT analysis can be countered in the negotiations through specific measures or proposals.

For example, if a company, through the SWOT analysis, finds that one of its weak points is a lack of consumer familiarity with its products, the negotiator might overcome this weakness in negotiation with prospective agents in the target market by offering promotional allowance. At the same time, the negotiator may use one of the company’s strength identified through the SWOT analysis, that of the high quality of the firm’s wooden cabinets, to convince the prospective agents to work with the firm on favorable terms.

Assessing BATNA

By assessing its BATNA (i.e., the best alternative to a negotiated agreement), a party can greatly improve the negotiation results by evaluating the negotiated agreement against the alternative.8 If the negotiated agreement is better, close the deal. If the alternative is worse, walk away.

The BATNA approach changes the rules of the game. Negotiators no longer see their role as that of producing agreements, but rather as making good choices. If an agreement is not reached, negotiators do not consider that a failure. If a deal is rejected because it falls short of a company’s BATNA, the net result is a success, not a failure.

BATNA is affected by several elements; namely, alternatives, deadlines, interests, knowledge, experience, negotiator’s resources, and resources of the other party. Any change in these elements is likely to change the BATNA. If, during the discussions, the negotiator obtains new information that influences the BATNA, he or she should take time to review the BATNA. BATNA is not static, but dynamic, in a negotiation situation.

The BATNA should be identified at the outset. This way an objective target that a negotiated agreement must meet is set, and negotiators do not have to depend on subjective judgments to evaluate the outcome. As the negotiation proceeds, the negotiator should think of ways to improve the BATNA by doing further research, by considering alternative investments, or by identifying other potential allies. An attempt should be made to assess the other party’s BATNA as well. The basic principle of BATNA is this: Never accept an agreement that is not at least as good as the BATNA.

Going into Negotiations

When conducting business negotiations, executives should keep in mind certain points that may arise as the discussions proceed.

• Situations to avoid during the negotiations: conflict, controversy, and criticism vis-à-vis the other party

• Attitudes to develop during the talks: communication, collaboration, and cooperation

• Goals to seek during the discussions: change (or, alternatively, continuity), coherence, creativity, consensus, commitment, and compensation

In business negotiations, particularly those between executives from different economic and social environments, introducing options and keeping an open mind are musts for establishing a fruitful, cooperative relationship. Experienced negotiators consider the skill of introducing options to be a key asset in conducting successful discussions. Giving the other party the feeling that new ideas proposed have come from both sides also contributes greatly to smooth negotiations.

The goal in such negotiations is to reach an agreement that is beneficial to both parties, leading to substantive results in the long run, including repeat business. To negotiate mutually beneficial agreements requires a willingness to cooperate with others. The discussions should, therefore, focus on common interests of the parties. If the negotiations come to an impasse for any reason, it may be necessary to refocus them by analyzing and understanding the needs and problems of each party.

The approach to business negotiations is that of a mutual effort. In an international business agreement (whether it concerns securing an order, appointing a new agent, or entering into a joint venture), the aim is the creation of a shared investment in a common future business relationship. In other words, a negotiated agreement should be doable, profitable, and sustainable.

Plan of the Book

In today’s global business environment, you must negotiate with people born and raised in different cultures. Global deal making has become a key element of modern business life. To compete abroad, you need skills to negotiate effectively with your counterparts in other countries. This book provides insightful, readable, and well-organized material about the conceptual and practical essentials of international business negotiations.

The book is divided into five parts. Part 1 covers an overview of global negotiations. Discussed in Chapter 1 are a number of variables relative to negotiation environment and negotiation setting. Of these, one environmental factor and one setting factor stand out as having the biggest effect in global negotiations. These are influence of culture and choice of proper negotiating style. Part 2, made up of Chapter 2 and Chapter 3, is devoted to the negotiation environment and setting. Chapter 2 examines the important role of cultural differences in global negotiations, and Chapter 3 discusses the appropriate negotiation style for successful results.

The negotiation process is examined in Part 3. The subject is covered in Chapters 4 to 9. Chapter 4 deals with prenegotiation planning. Initiating global business negotiation and making the first move are covered in Chapter 5. In Chapter 6, trading concessions are examined. Chapter 7 explores price negotiations. Closing negotiations is covered in Chapter 8. Chapter 9 focuses on renegotiations.

The four chapters, Chapter 10, 11, 12, and 13, in Part 4 deal with negotiation tools. The subject of Chapter 10 is communication skills for effective negotiations, while Chapter 11 is devoted to demystifying the role of power in negotiations. Chapter 12 examines management of negotiating teams. Chapter 13, the last chapter in Part 4, focuses on developing organizational capabilities for negotiations. Finally, Part 5 includes five chapters: Chapter 14 is devoted to negotiating intangibles; Chapter 15 explores online negotiations; Chapter 16 examines gender role in cross-cultural negotiations; Chapter 17 focuses on negotiations by smaller firms; and Chapter 18 deals with negotiating via interpreters.

Summary

For most companies, global business is a fact of life. That means executives must negotiate with people from two or more different cultures. This is more difficult than simply making deals with people who share one’s own culture. Therefore, it is important to learn fundamental principles of global business negotiations.

This chapter introduces the global business negotiation architecture and its three aspects: negotiation environment, negotiation setting, and negotiation process. The environment defines the business climate in which negotiation takes place. The setting specifies the power, style and interdependence of the negotiating parties. The negotiation process involves planning prenegotiation, initiating global business negotiation, negotiating price, closing negotiations, and renegotiating.

The next topic concerns negotiation infrastructure, which includes assessing the current status of a company from the viewpoint of global negotiation and assessing the BATNA (i.e., best alternative to a negotiated agreement).