Chapter Two

Artists' Books

The artist's book is a conquest of new territory.

Some of the most innovative crossover picturebooks fall into the category of what have been termed “‘artists' books' for children.” Although artists' books have been called “the quintessential 20th-century artform,”1 the definition and the term itself are still the subject of much debate. This study adopts the term “artists' books,” as it has become the most widespread, but often “artist's” is written in the singular or even without the apostrophe. Numerous other labels are also used to refer to these books, including book art, bookworks, and book objects. Often artists' books are defined in terms of what they are not, and one website begins by categorically claiming: “They are not children's books.”2 In fact, some of the most innovative artists' books are intended for young readers. Unfortunately, they are, for the most part, not well-known, unobtainable, and overlooked by critics. In France, “les livres d'artiste pour enfants” have received some scholarly attention, for the most part thanks to Les Trois Ourses, an association founded by several librarians in 1988 to promote artists' books for children and make them available to French readers.3 The French publishing house Éditions MeMo, which collaborates with Les Trois Ourses, specializes in artists' books for children from the past as well as the present. In Italy, Maurizio and Marzia Corraini, who began working with Bruno Munari in the 1970s, reedited titles which had previously been difficult to obtain, making them available not only in Italian, but also in English and French. In the English-speaking world, however, artists' books for children have been virtually ignored and, with very few exceptions, have received only passing mention by critics.4 In his study of artists' books, Stephen Bury cites the “children's book” as an example of the genres into which the artist's exploration of the book extended, and his list of works includes Bruno Munari's Prelibri and Andy Warhol's Children's Book, while Johanna Drucker's seminal The Century of Artists' Books, first published in 1995, devotes a couple of sentences to Munari and mentions Dieter Roth's Kinderbuch (Children's book) in very brief terms.5 Yet artists' books constitute one of the most influential and exciting areas of crossover literature.

The picturebooks examined in this chapter challenge not only the boundaries between adult books and children's books, but the boundaries of the book itself. Many of these innovative works question the conventional codex form, which dictates standard-size pages bound in a rigid sequence. Innovative experimentation with format and design has resulted in books that are also art objects and are sometimes referred to as “object-books” or “book-objects,” the latter term being preferable since they remain first and foremost books. The Italian designer Bruno Munari uses the term “libro-oggetto” (book-object) to refer to several of his groundbreaking works and the Swiss artist Warja Lavater refers to the celebrated series of imageries that she began publishing in the 1960s as “livres-objets” (book-objects).6 In book-objects, the narrative is told as much by the physical form as by the text and images. For these artists, the book is not merely a container for text and images, but a concrete, three-dimensional object. They explore every facet of the book and use all the resources of bookmaking, such as typography, paper, and binding, to tell the story.7 Munari worked as a book designer before he began creating his own children's books in the 1940s. The Japanese artist and designer Katsumi Komagata spent a number of years working as a designer in the United States in the 1980s before founding his own publishing house, One Stroke, in Tokyo in 1990, in order to bring out his unconventional books. The works of these artists constitute a provocative reflection on the very structure of the book.

Although these books are sometimes designated as “‘artists' books' for children,” they appeal widely to adults as well. Indeed, some adults question their status as children's books. Disconcerted by their enigmatic, interactive nature, they feel that these books are unsuitable for young readers, even when they are addressed explicitly to that audience. Limited print runs and high production costs may result in a price tag that is prohibitive for most readers of any age, making them predominantly collectors' books. Not all artists' books are expensive, however, and artists who create books with a young audience in mind are generally particularly concerned with making them accessible to a wider public. However, even reasonably priced artists' books are often sold in art galleries and museum gift shops rather than children's book stores, while libraries are reluctant to lend them if they are fortunate enough to have them in their holdings. The fragile nature of many of these works often discourages adults (parents as well as librarians) from allowing them into the hands of children. Artists' books thus often have the paradoxical status of being children's books that are kept away from children at all costs. The new and exciting possibilities of these versatile books explain their appeal with young readers. Children enjoy the playful, interactive nature of these works, while adults admire the artist's ingenuity. Artists' books offer readers of all ages innovative and challenging books of exceptional aesthetic quality.

Early Experimentations

It is often pointed out that this art form did not really begin in earnest until the 1960s. However, a number of striking examples of artists' books for all ages were produced much earlier. At least one eighteenth-century artists' book has a crossover audience. Like most of the works by the British poet, painter, and engraver William Blake, Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794) combines text and image using the technique he called illuminated printing. The introductory poem, which was first published in Songs of Innocence in 1789, states that all children could take pleasure in hearing the songs he had written. Over the past two centuries, children have indeed taken pleasure in Blake's poetry. Nancy Willard, who first read Blake's work at the age of seven, published the award-winning picturebook A Visit to William Blake's Inn, with illustrations by Alice and Martin Provensen, in 1981. The subtitle, “Poems for Innocent and Experienced Travelers,” is a direct reference to the poet's work, and the author reminded me, in a letter dated March 21, 2000, that Blake wrote his happy songs “in a book that all may read,” and that he also tells us that “every child may joy to hear” them. Willard's book of magical poems about life at an imaginary inn run by William Blake and staffed by dragons that “brew and bake” and angels that “wash and shake” the feather beds became the first book of poetry to win the coveted Newbery Medal. Like Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Willard's picturebook is intended for a crossover audience.8

At the end of the nineteenth-century and the beginning of the twentiethcentury, the artists of the Vienna Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshops) completely rethought the children's book. The Vienna Workshops were founded with the intention of uniting the fine and applied arts to create beautifully designed objects of all kinds, including books. The members experimented with format, page layout, typography, and text-image relationship. The desire to communicate to children the cultural significance of beautiful books led to cheaply produced but high quality, artistically designed publications. The special character of children's book production at the time was largely due to individual publishers, such as Verlag der Wiener Werkstätte and Martin Gerlach & Co., as well as the Viennese art schools. These works demonstrated a wide range of the techniques possible in book art, including lithography, woodcuts, stencils, and so forth. Of particular note is the Gerlachs Jugendbücherei, which became famous well beyond Austria's borders. Between 1901 and 1920, thirty-four volumes were published in the famous series, each illustrated in colour by a different artist. Die Nibelungen, which was published in 1909 as volume 22, offers an excellent example of the trends of the Vienna Workshops. Carl Otto Czeschka, a prominent member of the Vienna Secession and a designer for the Vienna Workshops, is responsible for the illustrations and the design of the text, which was adapted from the ancient tale of knightly honour by Franz Keim. Die Nibelungen is a rather unassuming little book that gives readers no indication of the riches to be found between the rather plain covers. The sixty-seven-page book features eight double-page spreads printed in blue, red, black, and gold, as well as numerous small black-and-white vignettes, initials, and head and tail pieces. The text is written in gothic characters and all the pages, whether they contain text or illustrations, are framed by an ornamental border. This eye-catching frame highlights the small framed vignettes that are centred on a white background. An atmosphere of ritual and pageantry dominates the illustrations, which are reminiscent of the Byzantine imagery that characterizes the work of the Austrian artist Gustav Klimt. Czeschka's striking, abstract figures are solemn and ceremonial, while the décor is highly stylized. The decorative stylisation that was popular in applied arts at the time pervades the illustrations, where it is used for items as varied as wave foam, a ship's sails and figurehead, floor tiles, even horses and birds of prey. The geometric motifs and stylistic ornamentation of the bedclothes, draperies, clothing, armour, and weapons, as well as the use of the gold colour, evoke Klimt's “Golden Phase,” so-named because paintings such as Der Kuss (The kiss, 1907–1908) contained gold leaf. Die Nibelungen is considered the best volume in the popular series and one of the finest examples of the Art Nouveau illustrated book.

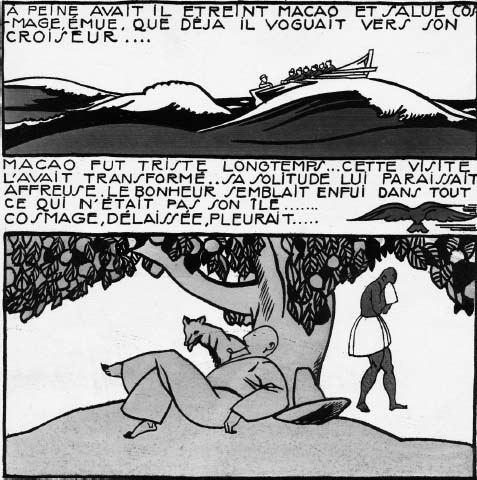

The increasing interest of painters, sculptors, and designers in children's books at the beginning of the twentieth-century resulted in some very revolutionary picturebooks. 1919 saw the publication of one of the great forerunners of the contemporary picturebook, Macao et Cosmage ou L'expérience du bonheur (Macao and Cosmage or The experience of happiness), which was written and illustrated by the French painter and illustrator Edy Legrand. It was the first picturebook for children published by the Éditions de la Nouvelle Revue Française or NRF (the original name of the leading French publisher Gallimard), and it remains one of the most important books in the history of children's book illustration. Macao et Cosmage is the work of a painter at the beginning of his career; Legrand completed the book when he was only eighteen years of age. The artist would go on to become one of the most important illustrators of the twentieth-century, but his later work does not rival the brilliant daring, originality, and visual impact of Macao et Cosmage. Legrand's work marks a significant break from the romantic styles of illustrators such as Arthur Rackham, Edmund Dulac, and Kay Nielsen, who were popular in the early twentieth-century, the so-called “Golden Age of Illustration.”

Macao et Cosmage contains fifty-four full-page engravings, vividly coloured by hand in the pochoir process. The book was revolutionary for a number of reasons, most notably for the reversal of the conventional text-image relationship. The text is minimal (some pages are wordless) and the major role is attributed to the illustrations, which carry the narrative. In addition, the artistically handwritten text becomes a component of the image itself. Some pages consist of a single plate, while others are divided into two asymmetrical images. The page layout is further diversified by the fact that many of the images are framed by a solid, black, handpainted border, while others remain unframed. The author-illustrator experiments with typography: the placement of the text varies from page to page, and can be found within the frame, outside the frame, framed between two images, or actually framing the image itself.

Figure 2.1 Die Nibelungen, interpreted by Franz Keim, illustrated by Carl Otto Czeschka, Verlag Gerlach und Wiedling, 1909, Digital Image © The Museum of Modern ArtLicensed by SCALAArt Resource, NY, reprinted by permission of The Museum of Modern Art.

Figure 2.2 Macao et Cosmage ou L'expérience du bonheur by Édy Legrand, La Nouvelle Revue Française, 1919.

A few of the illustrations seem to herald the graphic novel. A short foreword addressed to the child reader and signed familiarly “Your Friend, Edy-Legrand” insists on the importance of the images. Child readers are advised to look attentively because the author “only tell [s]” the story of Macao and Cosmage, whereas “the colours, the slightest objects, the smallest animals have a raison d'être” that they are intended “to discover” for themselves. Macao et Cosmage broke with standard publishing practices of the early twentieth-century. It is a large book with a square rather than rectangular format, which was highly unusual at the time. Unlike the carefully bound and costly books, with elegant tipped-in plates on fine paper, that were prevalent, Legrand's book had bold illustrations on course paper and it was quite inexpensive. It was an early attempt to make high quality books available to children of all economic backgrounds. While very fine copies of other prominent illustrators of the same period, such as Rackham and Dulac, are plentiful today, even a very good copy of Macao et Cosmage is quite rare.

It is not only the format of Macao et Cosmage that is innovative, but also the content. The author's highly critical attitude toward industrial and technological progress was unusual at the beginning of the twentieth-century. The anti-colonial perspective he adopts was also ahead of his time. The eponymous protagonists, a white man and a black woman, are portrayed and named on a striking doublespread that precedes the foreword and the title page. Their idyllic existence in harmony with nature is brought to an abrupt end when the uncharted paradisiacal island is discovered, and “an army of soldiers, colonists, civil servants, and scholars” arrives, bringing “blessed civilization.” Eventually, Macao turns his back on the progress that was to have brought him happiness. The ending of the book seems quite bleak, especially to adult readers, but in the foreword the author offers the child addressee a glimmer of hope, saying that the story would be “sad” if he wasn't convinced that Macao and Cosmage “are happy today….” The book has a very philosophical message that is encapsulated in the final line of the foreword: “The only mystery in life is penetrated when one knows where one's happiness lies.” In the last unspoiled corner of the island (the image depicts two trees by a puddle-sized pond on a barren mountain), an elderly Macao finally “experiences happiness.” The ultimate message is nonetheless pessimistic, as the last page of the book states: “Child! Macao was a wise man but the governor was right!” The relentless march of “civilization” and “progress” cannot be reversed. Macao et Cosmage played an instrumental role in establishing a new path for children's book illustration. However, because the author forbade the republication of Macao et Cosmage in 1947, it was not available again until 2000, when the French children's publisher Circonflexe offered a faithful reproduction targeted at ages six and up.

In the early years of the twentieth-century, there was a widespread search among avant-garde artists in many countries for innovative styles that would reflect the new age. European artists in particular sought to break down the traditional borders between non-visual art and visual art. The Russian avantgarde artist and designer El Lissitzky designed his first suprematist book, About Two Squares, while teaching in Vitebsk with Kazimir Malevitch. Published in Berlin in 1922, the children's book is a homage to Malevitch, whose Black Square initiated suprematism in 1913. The “grammar” of this art movement was based on simple geometric forms (notably the square and circle), which could communicate directly with everyone and be applied to all creative fields, including books. About Two Squares is at once a picturebook and a manifesto, in which Lissitzky offers a revolutionary rethinking of the children's book and the book in general, applying suprematism to the graphic arts. In “Our Book,” published in 1926, he reflects on what the contemporary book should become in the new age. The traditional form of the book (jacket, spine, sequential numbered pages) must assume a new shape capable of expressing the times. In the young Soviet Union of 1926, he wrote: “The book is becoming the most monumental work of art…. By reading, our children are already acquiring a new plastic language; they are growing up with a different relationship to the world and to space, to shape and to color; they will surely also create another book.” Lissitzky himself had already begun to create another book for the new era, a revolutionary book with a universal visual language that took into account “the semiliterate masses.”9 Paradoxically, this simplified, abstract narrative intended to ensure communication with everyone was considered by many to be elitist.

Lissitzky's avant-garde vision of book design and typography is best illustrated in About Two Squares, which presents a new way of arranging typography on the page and relating it to visual images. The letter and the word have a visual form like the image. In a large format book, Lissitzky tells his “suprematist tale” (he uses the Russian word “skaz” meaning “tale”) in what the title page describes as “6 constructions,” which resemble the artist's Proun compositions. The verso of the title page encourages the active participation of readers in an act of construction rather than of reading. The paradoxical directive “Don't read” at the top of the page is followed by a dynamic graphic line that zigzags down to the bottom left hand corner where “readers” are instructed to “Take—Paper Fold, Columns Colour, Blocks Build.” The two flying squares from afar,” one red and one black, descend upon the round red ball of the earth, where they discover “black alarming” chaos. The red square strikes a downward blow that shatters the chaotic black world of three-dimensional geometric shapes. The words that accompany this Construction also fall, contributing visually to the narrative. In the next illustration, a new, more orderly red world is reconstructed on a black square. In the final Construction, the red square hovers suspended over the transformed world while the much smaller black square exits the upper right hand corner. Lissitzky's children's book presents a clear social and political message that challenges the old social order and proposes a revolutionary transformation. His little tale is an allegory of a new society that young readers will help to build.

Lissitzky's dynamic images of geometrical forms being knocked down and rebuilt remind us of a child playing with building blocks, as Margaret Higonnet rightly points out. The innovative graphic design and typography are strikingly evident already in the title on the front cover, which, states Higonnet, “speaks like a child's rebus.”10 On a stark white background, the word IIPO (ABOUT) appears in small, slanted letters before a large black numerical “2” and the pictorial image of a red square. Lissitzky combines word, number, and pictorial image in a single visual language. A fine black line forms a large square that frames the title on the cover and each of the images in the book. Only the author-illustrator's name figures discretely at the bottom of the cover rather like an artist's signature on a painting (the two words of his name meet on a diagonal so that they share the “L”). Lissitzky bends all the rules of conventional typography in the brief fragments of text under the images, varying the type size and style, mixing upper and lower case, rotating letters, setting words on a diagonal, combining lines and words, and so forth.

The open ending on the last page, which is translated in the English version as “Here it ended, further,” could be interpreted as an encouragement to the reader to continue the work of the two squares: “This is the end, continue.” The transformation of society and humankind is a never-ending process. Lissitzky explicitly targets a crossover audience. On the second page, he dedicates the book “to all, to all children.” The large white “P” that begins the Russian word for children (ribiatam) is set on a solid black rectangular background and tilted backward on the diagonal, as if poised to propel forward into the future. The book's creator also mentioned the intended audience in Typographical Facts: “In this tale of two squares I have set out to formulate an elementary idea, using elementary means, so that children may find it a stimulus to active play and grown-ups enjoy it as something to look at.”11 The square protagonists are introduced rather like the actors in a play. In “Our Book,” Lissitzky refers to the triumph of cinema and the “new media which technology has placed at our disposal.” About Two Squares is an attempt to give the book a “new effectiveness… as a work of art” by mimicking the new media. “The action unrolls like a film. The words move within the fields of force of the figures as they act: these are squares.”12 Lissitzky's children's book was quite successful: the 3,000 copies of the book produced and sold in 1922 was a significant number for that time. In 1990, Artists Bookworks in the United Kingdom made this seminal book available to English-speaking readers by releasing a facsimile reprint with English translations printed on a transparent overlay to register over the original Russian. According to the website of the MIT Press, which published an edition the following year, Lissitzky's book “marked the beginning of a new graphic art and is among the most important publications in the history of the avant-garde in typography and graphic design.” The revolutionary book, which attempts to address children in an abstract language, had a profound influence on other artists creating books for all ages.

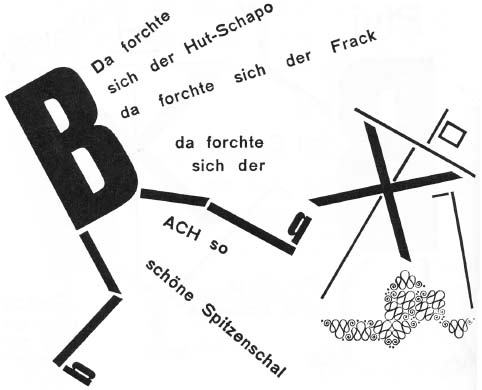

Another very innovative children's book, Die Scheuche: Märchen (The Scarecrow: Fairy Tale), was published in Hannover, Germany in 1925 by Kurt Schwitters, one of the major figures of German Dadaism, famous for his Merz collages and assemblages. He was a friend and collaborator of Lissitzsky, who published his 1923 manifesto, “Typographie der Typographie,” (Typography of Typography) in Schwitters's Merz magazine. In spite of the revolutionary nature of Schwitters's children's books, they are not wellknown.13 The first two children's books he published in collaboration with the talented artist Kate Steinitz, Hahnepeter (Peter the Rooster, 1924) and Die Märchen vom Paradies (Paradise fairy tales, 1924), are more traditional than Die Scheuche despite the typographic experimentation (variations of type and size, a tilted layout of words, etc.). Schwitters and Steinitz hoped to create a whole series of “children's books of our times, yet timeless.” De Stijl founder Theo van Doesburg, who had published a Dutch version of About Two Squares, suggested they make an “even more radical [picturebook], using nothing but typographical elements.”14 Schwitters was responsible for the text of Die Scheuche, but he collaborated closely with Van Doesburg and Steinitz as well as the talented typesetter Paul Vogt on the typography, layout, and design of the avant-garde book. The tale was brought out simultaneously as numbers 14–15 of Merz and by Apossverlag (an acronym for Active, Paradox, Oppose Sentimentality, and Sensitive), a pressmark created by Schwitters and Steinitz, as the latter was concerned that “the Merz label would prejudice teachers (not children) against these new fairy tales for our times.”15

Die Scheuche was influenced by constructivism and De Stijl, two movements which had an important impact in Germany, particularly at the Bauhaus. Like Lissitzky, Schwitters experiments with new forms of typography and adapts his innovative ideas to a young audience. The Futurists had already combined various types and sizes of typefaces on the same page, but Schwitters takes this further, developing a revolutionary illustrative typography. He uses letters, words, sentences, and sounds as he would use any medium. Text is transformed into image in illustrations entirely composed of typographical elements. In keeping with Dada literature, Die Scheuche is a nonsense text, but Schwitters also borrows the conventions of the fairy tale, including the formulaic incipit, to tell the revisionist tale of a scarecrow who “once upon a time” was well dressed in a top hat, tux, cane, and beautiful scarf. It is an absurd, slapstick story in which the elegant Scarecrow is pecked and mocked by Monsieur le Coq and his hens, beaten and cursed by the farmer, and then stripped of his fancy garments by the ghosts of their former owners. The bodies of the flat characters are composed of very large capital letters, to which other typographical elements are added to form legs, feet, arms, etc. The eponymous protagonist is largely constituted of an “X,” which represents his tux, while the Bauersmann (farmer) is a “B” that gives him a protruding belly. Paul Vogt willingly worked with these new typographical ideas, agreeing for example to cut the large “O” they needed for the body of Monsieur Le Coq. Nor did he refuse, as Steinitz says “every ordinary typesetter would have,” to set “the big B slantwise” to allow the angry man to boot the useless Scarecrow.16 This particularly dynamic page is one of the best known images from the book. The Scarecrow's top hat is made up of a black square and a straight line, his cane of two lines, and his beautiful lace scarf of curlicues and loops. These letter-characters are somewhat recognizable figures, especially Monsieur Le Coq.

The size of the letters and words as well as their organization on the page all help to carry the narrative. The hens peck in a circle around Monsieur Le Coq, as the farmer grabs the scarecrow's cane. As in Dada sound poems, the tone and emphasis of voice in which the words should be read is suggested, for example, the capitalization of “ACH” in the refrain-like line: “ACH so schöne Spitzenschal” (OH such a lovely lace scarf). In his quest for a new visual language, Schwitters creates a very rhythmic narrative that is at once graphic and sonorous. The artist's interest in théâtre is evident in the dramatic page layout of the book. In the congested closing scene, the figures are all crowded toward the right side of the page “as if the characters in the drama were all exiting together at one side of the stage.”17 Like Macao et Cosmage and About Two Squares, Die Scheuche is not only revolutionary in form but also in content. The nonsensical revisionist tale can also be read as a political allegory, as both Margaret Higonnet and Jack Zipes point out.18 The pretentious Scarecrow is brought low by the hungry birds and his belongings are returned to their rightful owners. The darkness brought on by the farmer's violence, when he grabs the cane from the scarecrow, is replaced by light when a youth takes possession of the cane. Die Scheuche was a very revolutionary work far ahead of its time, and it has only recently begun to receive serious critical attention. As in the case of Legrand's Macao et Cosmage, Schwitter's children's book is perhaps his most original work.

Figure 2.3 Die Scheuche: Märchen by Kurt Schwitters, Kate Steinitz, and Theo Van Doesburg, Apossverlag, 1925.

In 1937, the French writer Lise Deharme, one of the muses of surrealism, published Le Cceur de pic (The Heart of spades or The woodpecker's heart or The pick-axe heart, a play on words because spades in French is “pique,” while “pic” means “woodpecker” as well as “pick”), a book of short poems for children, accompanied by twenty black-and-white still life photographs by Claude Cahun, a prominent figure of the Parisian avant-garde. Their project fascinated the surrealists André Breton, Man Ray, and Robert Desnos. Le Cœur de pic has the distinction of being the only book for children ever published by José Corti, one of France's most prestigious publishing houses. Its founder, José Corticchiato, published the work of his surrealist friends, including André Breton and Paul Éluard, who wrote the preface of Le Cceur de pic. Deharme's “thirty-two poems for children,” which resemble nursery rhymes, are complemented exquisitely by Cahun's strange and disquieting photographs. Heterogeneous objects, such as flowers, leaves, branches, combs, bird's feathers, and feather pens compose striking, often surprising, little tableaux. As in all her work, Cahun uses photography to challenge the objectivity so often associated with this medium. The evocative atmosphere of these tableaux combines fantasy, mystery, humour, even cruelty. Ordinary objects are used to create a mysterious, strange world of the imagination. One of the photographs depicts three shoes on a set of wooden steps leading down into the darkness. Among them is a glass clog decorated with a white flower, evoking reminiscences of Cinderella's glass slipper. The accompanying text is equally enigmatic, beginning and ending with the same haunting lines: “three little shoes / my shirt burns me / three little shoes / climb up the stairs” (43). A tiny doll's hand, severed from its body, appears in a number of the symbolic photographs. Like many of the avant-garde children's books of the early twentieth-century, Le Cœur de pic is not well known, although it was republished in 2004 by Éditions MeMo. The French publisher recognizes the book as an object, one that is intended for all ages. They insist on their website that appreciating “a beautiful object” is not limited to a particular age group and therefore their books are intended to appeal to “young and old alike.”19 It is a belief and ambition shared by all the artists discussed in this chapter.

Breaking New Ground with Book-Objects

In the 1950s, Italian designers, notably Bruno Munari and Enzo Mari, began to use artistic and graphic language to create exceptional works for children, based on their observations of children's learning styles. The multi-talented Italian artist Bruno Munari, whom Picasso called “the new Leonardo,” had a significant influence on the editorial world throughout much of the twentieth-century. A painter, sculptor, designer, maker of toys, and architect, Munari was also an illustrator and author for both children and adults. As a young artist in the 1930s, Munari was involved in the Futurist experiments with bookmaking and creating metal books from tin cans. He illustrated Tullio d'Albisola's verses in the second famous Litolatta book, L'anguria lirica (The lyric watermelon, 1934). Although the text-image relationship is rather conventional, the format of this book-object is revolutionary: from the pages to the binding it is entirely constructed from tin. Munari would never cease to explore and question the conventions of the codex (binding, standard-size pages, fixed sequence, etc.), in order to find new structures for the book.

Munari's interest in children's books began as a result of his personal relationship with his son, whose birth in 1940 inspired his first games and books for children. In 1942, Munari began working as a graphic designer with the Italian publisher Giorgio Einaudi, and in the 1970s he directed Einaudi's picturebook series Tanti bambini, in which his innovative LAlfabetiere (first published in English in 1960 as ABC) was republished.20 The daring innovation that defines all Munari's books is especially evident in those addressed to children. For this reason, his children's books have always drawn the attention of adults. The groundbreaking book Nella notte buia (English trans., In the Darkness of the Night), published in 1956, has taken on cult status and become a landmark in children's publishing, but its appeal is not limited to young readers. Corraini markets Munari's classic Nella nebbia di Milano (1968; English trans., The Circus in the Mist) as a book-object that actively involves the reader, whether “adult or child.” A special place is devoted to Munari by Corraini, which bills itself as a publisher of “both ‘artists’ books and children's books.”

Like Bruno Munari, Enzo Mari was one of the most provocative and influential Italian designers of the latter half of the twentieth-century. He was also a writer, artist, and art theorist, who, sometimes in collaboration with his wife, Iela, produced several very innovative children's books. Each of his creations is the result of careful analysis and research. Mari's theoretical ideas on aesthetics and perception, expressed in books such as Funzione della ricera estetica (Function of esthetic research, 1970), were demonstrated visually in his picturebooks. The designer had already shown his interest in children in 1957 when he created the Sedici animali (Sixteen animals) puzzle for the Italian company Danese, which was founded in Milan at the end of the 1950s, by Bruno Danese and Jacqueline Vodoz, in order to produce unique objects by artist-designers (these were exhibited in their showroomgallery). Danese's meeting with Bruno Munari and Enzo Mari in 1958 led to the production of many innovative creations, which included books as well as games and other objects. Mari's puzzle is composed of sixteen wooden animals that fit into one another like a jigsaw puzzle. This puzzle-object functions as both a toy and a work of art and is appreciated by children as well as adults. A classic icon of twentieth-century design, it has gone through a number of re-editions. The most recent limited reissue sells for 341€, which means that it is most likely bought for the enjoyment of an entire family. When Enzo Mari addresses children, whether in toys, games, or books, his goal is to stimulate their imagination and their creativity; in so doing, he manages also to appeal to adults.21

As in Italy, designers and artists in other European countries were experimenting with the book as an object. The Swiss-German artist Dieter Roth (he later changed his name to Rot), who eventually settled in Iceland, is an extremely diverse artist well-known for his highly influential artists' books, some of which were produced for children. A poet as well as an artist, Roth chose the book as his medium of exploration and he became a pioneer of the modern artists' book. In the mid 1950s, he began deconstructing the formal qualities of conventional books (flat pages, traditional binding, fixed sequence, etc.) and proposing alternative structures. In Bok (Book, 1958), Roth cut holes in the pages and did away with the codex, permitting the reader to organize the pages in any order, while Daily Mirror (1961) was composed of the found material of a newspaper cut into 2 cm squares bound as a 150-page book. One of his best-known books is undoubtedly Literaturwurst (Literature sausage, 1961), which consisted of a sausage skin stuffed with ground up novels and mixed with spices and ingredients from sausage recipes. However, his first, and perhaps most remarkable books, are children's books; with them he began the exploration of alternative book structures that would mark all his work. His first children's book, titled simply Kinderbuch (Children's book), was conceived in 1954 for the son of the German dramatist and concrete poet Claus Bremer. Roth's playful approach to the book was suited to a young audience, but publishing houses were reluctant to take on such innovative books. Roth was unable to find a publisher either in Switzerland or in Denmark, where he moved in 1955, and the first copy of Kinderbuch was discarded. When he moved to Iceland in 1957, Roth, along with the writer Einer Bragi, established the publishing company, forlag ed., which provided him with a new independence and lack of restrictions that were conducive to his innovative book concepts. The first title published was Kinderbuch, a square book containing twenty-eight letterpress cardboard pages, with hand-cut and die-cut holes, that are folded in half and spiral-bound. The innovative book consists of opart-like geometric shapes and patterns in various sizes and colours, and the perforations allow glimpses of patterns and colours from the pages beneath. The colours and shapes give the book a striking harmony and rhythm. Roth deconstructs the standard-size pages of the codex by varying the sizes of the pages. This children's book marked the beginning of Roth's production of artists' books. However, the previous year he had hand produced three copies of another children's book, titled Bilderbuch (Picturebook). It is another square picturebook, which consists of approximately twenty sheets of transparent colour foil with rectangular die-cut holes of various sizes in a springclip folder. Roth's two children's books were published together in 1976 in the collected works he edited with the Stuttgart editor Hansjorg Mayer. As in the case of Bok, the basic titles chosen by Roth for his children's books (Kinderbuch and Bilderbuch) reflect the fact that structural explorations of the book became the subject matter of the book itself. Kinderbuch remains one of the artist's best and most beautiful books.

The Swiss artist Warja Lavater has gained an international reputation with the innovative “imageries” or “folded stories” that she began publishing in the 1960s. She has referred to these mobile works as “radical” books and they seem to herald the trend that Eliza Dresang would describe forty years later in Radical Change: Books for Youth in a Digital Age (1999). In actual fact, Lavater does not consider them to be books at all, but rather “book-objects” or even sculptures. These versatile books can be read as double-page spreads, either in a conventional manner from left to right or from back to front, or they can be hung and read from top to bottom, or they can stand, allowing all the pages to be viewed simultaneously. Lavater created the prototype of her first folded book, Le Petit Chaperon rouge (Little Red Riding Hood) in New York at the end of 1959, in a minuscule format no larger than a stamp. The first tale to be printed, however, was William Tell, a co-publication between the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York and the Swiss publisher Basilius Presse in 1962. Le Petit Chaperon rouge: une imagerie d'après un conte de Charles Perrault (Little Red Riding Hood: An imagery adapted from a tale by Charles Perrault) would be published by the French publisher Adrien Maeght in Paris in 1965, inaugurating a series of six tales by Charles Perrault (in actual fact, five by Perrault and the Grimms' Snow White) that are undoubtedly her best known works. The final tale in the series, La Belle au bois dormant (Sleeping Beauty), was published in 1982. All of Lavater's imageries are printed from original lithographs by the artist. Special editions of several of these tales were also made for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Children quickly appropriated the expensive luxury books meant to be sold in museums to art lovers.

Katsumi Komagata describes his discovery of an “old-fashioned bookstore” in Paris, where “some wonderful books” produced by an artist using lithographs were treated as “art objects” by the bookshop owner.22 He is obviously referring to Lavater's books in the Librairie Maeght on rue du Bac. While the Japanese artist was working in the United States, he discovered Munari's books in the shop of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Like Munari, Komagata began creating books for children when his first child was born. As he explains in the blurb of Blue to Blue, he hoped these books would expand children's imagination. They are nonetheless crossover works and the artist “expect[s] both adults and children to be flexible when they read [his] picture books.”23 The Form and Colours website designed to promote Komagata's books in the United Kingdom (they are not well known in the English-speaking world) markets them as “books for adults and children alike,” which are “as much examples of book art for children as a delight for book lovers.” Komagata's first books for children were the Little Eyes series, ten small wordless books published, in 1990, after the birth of his daughter, Aï. The title is an intentional play on words, as Aï is a homonym of “eye,” but it also means “love” in Japanese. Perhaps the artist also had the homonym “I” in mind, in light of young children's preoccupation with their own person. The small books are made not only for “little eyes,” but also for “little hands,” so they are user-friendly and easy to handle for babies and toddlers. There is no binding; instead, a kind of paper case contains twelve cards, folded in three sections, which have to be opened, adding rhythm and movement to the act of reading because, as the artist reminds us, babies are constantly moving. Komagata considers it the “minimal book, the basis of the future book.” The artist was strongly marked by the books of Munari, whom he calls “the pioneer” in the field of “three dimensional action books.”24 In turn, Munari expressed his admiration for Komagata's work in 1994. Like Munari, the Japanese artist explores new structural formats for the book and new ways of reading it. The Komagata exhibition organized to mark the centenary of Munari's birth clearly indicates that the Japanese artist is the heir to Munari's pedagogical thinking and his playful and creative approach to the book as a three-dimensional object.25

Book-Games

Book-objects that involve a significant element of play are sometimes referred to as book-games. Munari's early books for children fall into the category of what he calls the “libro-gioco.” The books of the historic series he published in 1945, while he was a graphic designer for the publisher Mondadori, are all designated as “animati” (moveable books), and contain a variety of surprises, including flaps, inserts, and cut-outs. Although these devices later became commonplace in picturebooks, they were quite revolutionary at the time. Munari's remarkable books were created, as Komagata's would later be, with his own child in mind, as he had been unable to find anything he felt was suitable for his five-year-old son. In his view, the children's books available at the time were designed to appeal to the adults buying the books rather than the intended readers, so he tested his book projects on his son to ensure that they were effective.26 Under the simple title I libri Munari, seven of the planned series of ten books were published by Mondadori. All the books in the series have the same rectangular dimensions, but the number of pages varies from eight to twenty-four. In many of the books, Munari offers an alternative to the standard-size pages of the conventional book, using pages of different sizes.

The first book in the series, Mai contenti (Never content), was published in English both as What I'd Like to Be (1953) and The Elephant's Wish (1959). Like humans, the animals in Mai contenti are dissatisfied with their lives and dream of being something else. The humorous illustration on the cover depicts a blue fish with large ox horns and a yellow bird as the pupil of its eye. Like several books in the series, Mai contenti can be turned into a guessing game. Each animal's fantasy is revealed when readers lift the flap of a camouflaged insert positioned in the approximate area of the animal's mind. In this ironic, circular story, the elephant, “bored with being a big heavy animal,” dreams he is a bird, but the bird is “bored with flying and singing,” and wants to be a fish, the fish would like to be a lizard, the lizard dreams of being an ox, and the ox would like to be an elephant. The final line reminds the reader that “the elephant dreams too.” Thus Munari brings readers full circle and they can begin the book again.

The cover of the third book takes the form of a door and the title, Toc toc: Chi é? Apri la porta (Knock, knock: Who's there? Open the door; English trans., Who's There? Open the Door), invites the reader to open the door. The reader enters the book to become the protagonist of the story. Munari felt it was fundamental that children's books should not have a protagonist: “In my books the protagonist is the child him/herself… who opens the door in the book Toc toc: Chi e? Apri la porta, a book in which there are many characters…, but where there is no protagonist.”27 A cut-out in the cover forms a peep hole through which a bird peers, as if deciding whether or not to let the reader in. The title's question is repeated throughout the book, and this questioning of readers is a common strategy in Munari's children's books. The book consists of six doublespreads of different coloured paper glued one inside the other in decreasing size, the largest constituting the cover. Page size helps to tell the story, as the pages constitute doors and objects that must be opened to continue the narrative.28 They reveal ever smaller animals until all the pages, or portions of them, are visible simultaneously at the centrefold. On the first doublespread, the giraffe Lucia stands listening to a wooden crate from Verona (in the English translation, the animals are given common English names and the Italian cities are replaced by major European cities). Inside the crate, readers discover a zebra with a trunk from Lugano, which, in turn, contains a lion with a valise, and so forth. In the fourth book, Il prestigiatore verde, large flaps are also opened to reveal the magician Alfonso's surprises, but this time the flaps are not simply rectangular as they were in the previous book. On the first doublespread, the magician asks readers to guess what is inside a piece of furniture. A hexagonal flap opens to reveal the conjurer himself standing on a table. Surprise is an essential element of the playfulness of Munari's book-games.

The fifth book in the series, Storie di tre uccellini (A tale of three little birds; English trans., Tic, Tac, and Toc, 1957), is composed of three books within a book. This format allows Munari to expand the book's fixed structure by creating additional spaces within it. However, the format is intrinsically linked to the content. The mini-books tell the story of three birds who end up in a cage in the frame story of the larger book. On the cover, the yellow, red, and blue birds are depicted together behind bars that bleed off the page. Each minibook bears its own title: “Storia di Ciò” (The Story of Ciò), “Storia de Cià,” and “Storia de Cì.” Cut-outs are also used to show a bird or part of a bird on the pages beneath. In the sixth book, Il venditore di animali (Animals for sale), page size again varies according to the progress of the narrative. On pages of ever decreasing size, the animal salesman tries unsuccessfully to sell a child ever smaller exotic beasts, including a flamingo, a porcupine, an armadillo, a bat, and a millipede, but the child is not interested because of their strange habits. In the end, all the pages are partially visible, as in Who's There? A sheet on the final endpaper opens to reveal the humorous ending: the child would like a roast turkey with French fries. The green string that had joined the salesman's hand to each of the animals now joins a chicken leg to a fork.

The last book to be published in 1945 was Gigi cerca il suo berretto: dove mai l'avrà cacciato? (English trans., Jimmy Has Lost his Cap), which uses a series of inserts with flaps to take the reader on a search for Gigi's lost cap. In 1997, Corraini brought out two previously unpublished titles in the series, Il prestigiatore giallo (English trans., The Yellow Conjurer) and Buona notte a tutti (English trans., Goodnight Everyone), which also contain pages of different sizes and/or inserts of varying sizes with flaps to lift. Under the flaps of Goodnight Everyone, readers discover creatures sleeping: a boy under a cover in bed, a fish behind a rock in an aquarium, and a cat under a pillow on the couch. Munari reserves two surprises at the end: hidden under a large flap, which looks identical to an umbrella hanging from the attic ceiling, is a sleeping bat, while the final small flap reveals a wide-awake moon. Munari's game-books have lost none of their popularity with the children and parents of the digital age. In 2010, a complete set of I libri Munari was listed on Bloomsbury Auctions in Rome for 4000–6000 €.29

In 1965, Enzo Mari published Il gioco delle favole (The fable game), an inventive children's “book-game” that is, in fact, a book to be endlessly constructed, deconstructed, and reconstructed. The book-game consists of six cards that can be interlocked. With the simple elegance so characteristic of his work, the artist represents forty-six simple animals borrowed from old and new fables (lion, fox, bear, wolf, etc.), as well as natural elements (sun, moon, trees, plants, etc.) and some objects (an apple, a boot, etc.) that could be found in classic fairy tales. One illustration portrays a crow sitting in a tree above a fox, immediately evoking La Fontaine's fable “Le corbeau et le renard” (The crow and the fox) or Aesop's version “Corvus et vulpes.” Despite the simplicity of the animals, generally depicted in only one or two colours, they are very expressive thanks to small details, their poses, and even their colour. The artist does not necessarily use the appropriate colour: the previously-mentioned fox is a vivid red, as is a rabbit, while a bright yellow dog barks at a more traditionally coloured rooster. The cards can be put together in a multitude of combinations, stimulating creativity, storytelling, and imaginative play. Children can invent their own fables or entirely different kinds of narratives; the storytelling possibilities are endless. Since Corraini reissued Il gioco delle favole, it has had several reprintings. It is a timeless classic that is considered even today to be one of the most important and ingenious games designed for stimulating creativity.

The various strategies that Munari uses in his own game-books are shared with children, parents, and educators in La favola delle favole (The fairy tale of fairy tales, 1994), a large book-game that allows children to create “their own personal books to treasure and to read when they are great-grandparents.” The paratext clearly indicates that Munari targets this book-game indirectly at a crossover audience of children and future adults. The fifty-seven large pages are held together by two fold back clips, making them completely interchangeable. A preface, signed by Munari, provides some game rules concerning the construction of the book as well as the story. He suggests the use of coloured sheets of paper as a background to drawings done on transparent paper or the creation of “special effects” with cut-outs from the coloured sheets, then provides the materials that children need to physically create their story. La favola delle favole gives readers of all ages new insights into Munari's creative process in general.

Komagata has also published book-games with three-dimensional cards to colour, titled simply Workbooks: Red Series and Green-Yellow Series. In 1999, a special issue of the Japanese magazine Bessatsu Taikyo, titled “Let's play with picture books,” was devoted to unique picturebooks with a ludic element that often involves the format. Komagata's work was given special attention and a previously unpublished book, Are you OK?, was included in the magazine. It is perhaps not surprising that his card-style books in the Little Eyes series were labelled toys, which have a much higher tax rate than books, by a French customs officer when the artist sent them to Lyon for the “1, 2, 3 Komagata” exhibition in 1994. Munari describes the Little Eyes series as “a game for all ages.”30 The ten mini-books in the series are autonomous but combine to create one large book about the world around us. Inspired by Munari's Prelibri, they offer a similar encyclopedia for preschool children. A different theme or concept is introduced in each of the ten books, which constitute as many visual games to accompany the child from birth. The first three books were created when Komagata's daughter was six months old and are designed specifically for babies, whereas the remaining books are intended for slightly older children. His daughter's development and responses to visual stimuli continued to inspire his later works. Komagata thus uses his artistic skills in the service of neurological and socio-cultural development.

Number 1 in the series is appropriately titled First Look (1990) and is designed especially for “babies from 3 months.” For the first six books in the series, Komagata uses the same format: twelve double-folded cards in a cardboard case. Little eyes are presented with a variety of shapes and forms (circles, triangles, squares, etc.) in the first book, the only one entirely in black and white. By using cut-out shapes, Komagata playfully presents the concept of volume. Three of the books deal specifically with colours. Designed as a “second step for babies,” number 2 is an introduction titled Meet Colours. Number 3 invites readersviewers to Play with Colours by offering more complex and surprising interactions between forms and colours. Although the third book is described as “advanced for babies,” the Forms and Colours website informs potential buyers that “this set is great fun for and actually very popular with design-conscious adults.” Number 6 bears the interrogatory title: What Colour? and relates colour to its occurrence in nature (a black bird and red cherries decorate the cover). Number 4, One for Many (1991), examines the world of geometry using colourful forms in different configurations (on the first card a circle divides into two shapes), while number 5, titled 1 to 10, looks at numbers.

In the tradition of Munari, Komagata combines essential themes and concepts with art and play. Whereas books 4–6 are categorized as “learning for children,” the remaining books in the series are billed as “fun for children,” and the emphasis is on the play element. All the previous books adopted the double-folded card format, but Komagata adopts new formats for the subsequent books. In number 7, a theme-oriented book titled The Animals, folds are used in a different manner to create surprising effects that delight readers. The folds in each of the eight cards get increasingly larger, so that the fold behind is partially visible and an image is formed (whale, elephant, chicken with an egg, cloud, etc.). When the card is unfolded, the image changes in surprising ways, presenting a scene with several animals. The thematic approach is continued in number 8, Friends in Nature. By showing the rain following the fine weather in nature, Komagata introduces the cyclic recurrence of natural laws that is a major theme in his work. This book consists of four booklets, in which the picture undergoes subtle changes from page to page, changes which suggest a mini-story.

The last two books in the Little Eyes series, Walk & Look and Go Around (1992), are the most playful. The format requires the child to move in order to “read” these books. Both books consist of four cards which use accordion folding, but in a slightly different manner. In both cases, the cards depict images (themes or subjects) that change depending on the direction from which they are viewed. However, the cards in number 9 are three-sided, with the accordion-folded images on only one side. This format makes the cards easy to stand up and since the double images only occur on the accordionfolded side, the reader is obliged to move only slightly to view the two images. The last book is more complex, as the cards have images on both sides of the accordion folding, thus creating four different scenes on each card, for example, the four seasons or the four stages in a penguin's life. The absence of the two straight sides makes standing the cards more of a challenge. As the title suggests, children are required to “go around” the card to “read” it. The accordion-folded images of the last book are contained in four, long narrow sleeves that constitute a kind of puzzle. When they are put side by side in the correct order, they form the image of a bee near a large flower on one side and on the other a small boy looking up at what is presumably the same bee above his head. In this series, Komagata begins with the simplicity of forms but shows the complexity of their relationships. Readers of all ages will find their certainties questioned and their perceptions modified. On one website, readers are warned that they are expensive: “At $375 for all ten, these may be the kids books you never let the kid touch,”31 while a comment posted July 21, 2008 on Ohdeedoh.com, a website devoted to “home, design, and children,” states: “The books aren't cheap, but they will surely be enjoyed and later cherished as works of art.”

In 1996, Komogata published Motion in his Mini Book series, which also includes the books Shape and Scene. The books in this series take the form of a case containing twelve cards to be viewed on both sides. Motion is inspired by Book 2 of Munari's Prelibri, in which a stylized white man walks, jumps, and exercises. The simple image changes according to the viewer's angle. In Motion, the figure of a gymnast engages in similar movements around the square hole in the centre of the cardspages that constitutes his body. Munari considered the reading of books like his libri illeggibili to be mental gymnastics. In these two books, reading literally becomes a form of gymnastics, as children move about the work viewing and often imitating the figure. The work's innovative creativity was acknowledged when it won special mention at the Bologna International Children's Book Fair in 2000.

Artists' books have played an important role in the development of the concept of ludopedagogy or education through play. Artists like Munari and Komagata realize that artists' books can be playful tools capable of stimulating children's creativity, learning, and development. Play is an essential element of all their books and inseparable from the act of reading. Late in his career, Munari developed workshops for children based on what he called “Giocare con l'arte” (Play with art), leading the first at the Brera museum in Milan in 1976. Mari and Komagata have also led creative workshops for children in several countries. At the Children's Workshop of the Centre Georges Pompidou in 1965, children who were given Warja Lavater's accordion fold book, Le Petit Chaperon rouge not only viewed it and played with it, but actually “play[ed] it like a musical instrument.”32 This invasion of museums, art galleries, and other bastions of high culture by children, for the purpose of creative play, is characteristic of the often irreverent appropriation of high culture by popular culture in contemporary society. Artists' books are finding their way out of museums and into the playground.

Wordless Books

In many artists' books, the narrative is carried more by the images than by the text, which is generally minimal or non-existent. A large number of books that fall into this category are wordless. In 1949, Munari began publishing the famous series of books he called “libri illeggibili” (unreadable books) because they contain no words to read. As an artist, Munari did not really believe they were “unreadable,” but he warns readers who feel that only text can be “read” to expect a different language. His experimentations in these books were intended to discover if “it's possible to use the materials that make up a book (excluding the text) as a visual language…. Or can the book as object communicate something independently of the printed words?”33 The importance of the libri illeggibili to Munari is evident from the fact that he would continue to produce them throughout his lifetime. He proposes an innovative type of communication that involves neither text nor image. These books tell visual stories by means of format, binding, colour, paper, transparencies, perforated or torn pages, and inserts. According to Munari, these visual stories “can only be understood by following the thread of the visual discourse”34 A cotton thread literally carries the thread of the narrative in a number of these innovative books, but the thread never imposes a story, leaving readers free to construct their own narrative. The beginning and ending can occur anywhere in these versatile books. Munari's early libri illeggibili were handmade works in a single copy or very limited editions, but he later adapted his works for mass production. In 1984, Munari designed Libro illeggibile MN 1 especially for Corraini. The popular book is currently in its seventh edition (each edition having had a print run of thousands) and sells for a mere 3.50€. Munari created this libro illeggibile in a small, square format that is meant for tiny hands. A piece of string or, in the case of the most recent edition, a piece of orange thread, binds together the thirty-two small pages of brightly coloured heavy paper cut in a variety of shapes. Like the Libro illeggibile con pagine intercambiabili, created in 1960, this book has “interchangeable pages.” The conventional formal aspects of the book, such as the title page and colophon, are also missing from Munari's “unreadable” books. These book-objects can be displayed in a standing position, adding the dimension of the play of light and shadow on the coloured forms of the pages.

The “books without words” produced by Iela and Enzo Mari in the 1960s have become classics. The couple's graphic innovation revolutionized Italian children's literature. Enzo Mari has received much more critical attention than his wife, Iela, despite the fact that she published several picturebooks on her own in addition to those on which they collaborated. Their first books were conceived for their own children and, like those of Munari and Komagata, they were based on close observations of their young children. The first books they designed, La mela e la farfalla, translated into English as both The Apple and the Moth and The Apple and the Butterfly, and L'uovo e la gallina (English trans., The Chicken and the Egg, 1970), are wordless books which examine nature's circular life cycles. According to Enzo Mari, they conceived a series of six small, square books, in which the images were to clearly correspond to the represented object in appearance and scale. The apple, the butterfly, and the chicken are all on a scale of 1:1. Books were still conventionally rectangular, so the square format was quite unusual at the beginning of the 1960s. The absence of a cover and the spiral binding would allow readers to begin at any point, eliminating the traditional book's idea of a beginning and an ending in order to emphasize the theme of the eternal cycle. The Apple and the Butterfly was published by Bompiani in 1960, and, according to Iela Mari, the books L'uovo e la gallina and Mangia che ti mangio (English trans., Eat and Be Eaten) had already been planned for the same publisher.35 Enzo Mari admits that The Apple and the Moth was a total failure because the small book was lost among the large, coloured covers of the fairy-tale volumes that adults favoured at the time. In order to present them to other publishers, the two picturebooks were given a more conventional, larger format with a hard cover that gave them a beginning and an ending.36 Both books use striking visual graphics to tell circular stories of the cycle of birth, growth, and reproduction. Inside a red apple, an egg gives birth to a caterpillar which, in turn, burrows out and becomes a chrysalis and finally a butterfly in The Apple and the Butterfly. Then the whole cycle begins again. The Chicken and the Egg depicts a chicken laying an egg, the hatching of the egg, and the development of the chick, which, in turn, becomes a chicken. Unusual perspectives are offered: only the lower part of the body and legs of the chicken are visible as the egg is laid and one doublespread depicts the yellow and white interior of the egg on a shiny black background. These children's books demonstrate how Enzo Mari works with form in all his designs: everything superfluous is eliminated in a desire to achieve simplicity and to express the essence.

The picturebooks that Iela Mari published on her own share the same qualities as those created in collaboration with her husband. In her wordless picturebooks, the narrative is structured by changing forms and the cycles of nature. The first to be published, in 1967, was Il palloncino rosso, which appeared in English in 1969 as The Magic Balloon but was also published subsequently under the more accurate title The Red Balloon. In this surprising book, representational forms are continuously transformed from one page to the next in what Carla Poesio refers to as “a wordless poetic narrative.”37 A little boy inflates a red balloon, which takes off into the sky and attaches itself to a branch, where it becomes a red apple, until it falls to the ground and breaks apart, taking the shape of a large red butterfly, and then landing on a stem where it turns into a red flower. The hand of the same little boy picks up the flower which assumes the shape of an umbrella as storm clouds threaten. The final, striking illustration depicts the umbrella from above, so that readers glimpse only the boy's two little feet walking home. The metamorphosis loses some of its impact in the later, smaller edition of the book. The more extensive white space of the original edition highlights the fine line of the china ink and the transformations of the red object. The Red Balloon is easily understood by small children, but it is thought-provoking for adults as well. Iela Mari continues to explore the cycles of nature in L'albero (1972; English trans., The Tree and The Tree and the Seasons), in which the same scene is used to depict the silent beauty of the changing seasons. In Eat and Be Eaten, finally published in 1980, each spread depicts a predator pursuing its prey. With each page turn, the prey in turn becomes a predator. The Emme catalogue describes Mari's book as “a mortal Ring Around the Rosy of hunger and satiety….” The last children's title she published, Il paesaggio infinito (The infinite landscape, 1988), consists of sixteen eye-catching cards—depicting animals in a shifting landscape—that can be mixed and matched to create an ever changing narrative. Although Iela and Enzo Mari's picturebooks have a limited range of colours, the details and precision of the drawing are outstanding. They reproduce with remarkable accuracy the pattern on a butterfly's wings, the blossom on an apple tree, or the rough texture of a chicken's foot. The simplicity of line and purity of form combined with the playfulness of the artists' images make their books unique and timeless. Their experimentations on communication through the image resulted in wordless picturebooks that stimulate the imagination of readers of all ages.

Warja Lavater also began experimenting with visual communication in the late 1950s. Like Munari, Lavater was influenced by the Bauhaus movement. At a very early stage, she felt that the combination of codes and signs linked to forms and colours could create a kind of new language that would no longer be verbal, but visual. The artist refers to the visual code of her imageries as “pictorial language” or “pictograms.”38 The only text is the legend on the flyleaf at the beginning, which explains the elementary code based on colours and forms. Guided by the symbols, readers construct their own version of the story. According to Lavater, her pictorial language has its origins in traffic signals, whose efficiency as a visual code had struck the artist during her first visit to New York. While this influence is evident in many of her works, it is most clearly demonstrated in Die Rose und der Laubfrosch: eine Fabel (The rose and the tree frog: a fable), a charming little story about traffic lights which Lavater wrote to prevent her two-and-a-half-year-old grandson from crossing the street on a red light. The fable, which the artist considers to be her only “children's book,”39 was published in 1978 by a different editor from her other works.

Lavater's visual code remains the simplest and most effective in the first work that she conceived using this technique. In Le Petit Chaperon rouge, there are only eight icons and they are limited to dots (Little Red Riding Hood is symbolized by a red dot and the wolf by a black dot), with the exception of one rectangle and a squared “U” shape for the bed. Readers easily follow the movements of the little red protagonist as she moves from scene to scene. In later books, a proliferation of more elaborate icons results in a more complex visual code that is less easily decoded without referring closely to the legend. Even William Tell, which was published prior to Le Petit Chaperon rouge although it was created later, is already more complex. Some characters and motifs retain the earlier simplicity: William Tell is a blue dot, his son is a smaller blue dot, Gessler's hat is a red triangle, and the forest is once again a group of green dots. However, the Tyrant Gessler, the knights, and the soldiers are all represented by symbols that combine multiple shapes. The later Perrault tales are also more complicated. In Blanche-Neige (1974), Snow White is a black, white, and red dot that represents her three distinguishing physical features, the evil stepmother is a yellow dot with a black centre that symbolizes her black heart, and the dwarfs are red diamonds outlined in yellow as if they exude a golden aura.40 In Le Petit Poucet (1979), Little Thumbling's brothers are simple blue dots, but the protagonist is distinguished by a purple centre, which no doubt denotes his intelligence, and all are encircled by purple shapes symbolizing their bonnets. In contrast, Lavater did not deem it necessary to represent the distinctive headgear of Little Red Riding Hood in the earlier tale, even though it is an inherent part of her name. The symbols are even more diverse and complicated in Cendrillon, published in 1976. Cinderella is an elegant silver dot ringed with black and blue, and superposed with two matching blue ovals that represent her slippers. In the narrative itself, the icon is sometimes completely splattered with black to represent the cinders of the hearth. The elaborate nature of the visual language of this tale is well illustrated by the scene portraying Cinderella's arrival at the ball. In a colourful, fancy swirl of orange gown, the heroine enters the ballroom, where the prince, a richly decorated triangle with protruding swirls that evoke a moustache, is surrounded by his dot-guests and flanked by the two stepsisters, whose circular icons are now laden with gold ornaments. The king's small triangular servants and soldiers stand at attention, while the fancy, gold-crowned dots of the king and queen occupy a podium, and the simple dots of the proletariat gather outside the line that represents the palace walls.

Figure 2.4 Blanche Neige: une imagerie d'après le conte by Warja Lavater, 1974, copyright © Warja Lavater/SODRAC (2011).

Figure 2.5 Blanche Neige: une imagerie d'après le conte by Warja Lavater, 1974, copyright © Warja Lavater/SODRAC (2011).

Lavater seemed to feel that her visual code was not entirely adequate to tell Perrault's least known tale. La fable du hasard (The fable of fate), based on Perrault's “Les souhaits ridicules” (The foolish wishes, 1968) as retold by the Brothers Grimm in “The Poor Man and the Rich Man,” is the only book in the series that has any text beyond the legend. A handwritten foreword by the author appears on the first double-page spread. Even the narrative itself has some text, as the final two-page fold contains Perrault's moral, but the handwritten text is part of the image. The commas that separate the string of adjectives in the second line are replaced by a series of dots that trail down the page like cosmic dust and blend in with the other dots of the image. The text is necessitated in part by the much more complicated pictograms. The poor man and his wife are charmingly portrayed as two complementary green swirls outlined in yellow, which seem to hold hands, or rather tails. The rich man and his wife, on the other hand, are appropriately represented by two dissimilar, unequal, and detached vertical jagged lines. The amount of text is greatly increased in the legend, where detailed explanations are given along with the interpretation of the symbol. All of the icons, with the exception of those representing “serenity” and the descriptive “a good meal for each day,” are accompanied by at least one line of explanatory text. The symbol for the saddle is followed by a text of six lines, which includes the rich man's second wish that sticks his wife on the saddle. His other wishes are given beside the symbols for horse and rain, the latter being one of the few self-explanatory symbols. The icon for the sun needs no commentary, but the artist includes a complex idea from the Grimms' tale: “it burns the hard of heart, but it shines for the pure of heart.” Such abstract notions cannot easily be rendered visually, but the meaning of the penultimate double-page fold of the couple basking in the rays of a golden sun should be evident to most readers. The two swirls that represent the couple even seem to smile happily at each other (the pink shading around them gives them a rosy, blissful glow). The rather cluttered legend of this tale contrasts sharply with the simple legend of the first tale, and its heavy reliance on text makes this book less accessible to young children.

In some of Lavater's “Folded Stories,” which will be discussed in a subsequent section, the artist includes a summary that covers the entire back of the concertina folding rather than complicating the legend. This is the case for two tales published in 1965: Hans im Glück (Lucky Jack, Folded Story 14, 1965) and The Ugly Duckling (Folded Story 15, 1965), where the tale is told briefly in three languages (German, English, and French) on three folds each. In these books, the legend is in black and white even though the pictorial narrative that follows is in colour. Although an “old woman” figures in the legend of both tales, Lavater does not retain the same symbol but varies it slightly. While the majority of the symbols are quite abstract, some are more figurative, notably the dog's teeth in The Ugly Duckling. A few of the symbols lie midway between, as in the case of the icon for the old woman, which resembles a female figure kneeling with rounded back, bowed head, and breasts. The ugly duckling is a thick vertical line with a rounded top, to which two curlicues are added as wings to represent the beautiful swan. Although the swan is quite stylized in the black-and-white legend, it is much more figurative in the narrative itself, which is rendered in colour. The grey stick with a touch of orange for the beak gradually changes colour and shape throughout the story. A great deal of thought obviously goes into even the most abstract symbols. While the mother duck is represented by an almost complete circle, the pretty ducklings are a neat half circle, and the wild ducks are an untamed version of the half circle with sides that curve up in an unruly manner.

Lavater manages to infuse her visual retellings with suspense, drama, and energy. The impression of movement is particularly striking in La fable du hasard, where the very first image draws viewers into a spiral as they follow a wandering Fortune, disguised as a poor beggar, first to the house of the discordant rich couple who turn him away, and then to the house of the harmonious poor couple who immediately bid him enter. A series of very dynamic doublefolds depict the rich man jumping on his horse and riding after Fortune in ever larger loops that evocatively imitate the galloping horse, until he overtakes him and makes his three foolish wishes. The colourful, dramatic illustration of the bloody scene in which the huntsman arrives to rescue Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother are reminiscent of a smouldering volcano about to erupt, whereas a similar scene in Le Petit Poucet evokes an actual eruption. In both cases, the human contents of the villain's stomach are released unharmed in a spectacular graphic display of dazzling colour and dynamic movement. As the artist herself writes in the foreword to La fable du hasard, these classic tales are retold in a “new language,” a “visual language” that gives “complete freedom of interpretation” to the reader.

The French artist Jean Ache (pseudonym of Jean Huet) used a very similar visual code, which he called abstraction narrative, to recast several fairy tales in the 1970s. The geometrical shapes he employs to tell “Le Petit Chaperon Rouge” and “Cendrillon” in Le monde des ronds et des carres (The world of circles and squares), published in Japan in 1975, are strikingly similar to those used by Lavater. He also includes a legend at the beginning of the tale in both Japanese and French. Little Red Riding Hood is once again a red (or slightly orange) dot or “circle,” but the wolf is a black square. The wolf's symbol is somewhat complex, as it is divided into two triangular shapes by a jagged white line that represents its pointed teeth. Ache's geometric forms are not limited to squares and circles, as the volume's title suggests, and he also introduces into his narrative icons that do not appear in the legend. Ache's version of “Little Red Riding Hood” did not appear until ten years after Lavater's, but his “Cinderella” was published a year before hers. Further, he had already used the same visual code to retell “Le Petit Poucet” and “La Belle au bois dormant” in a collection of fables and tales titled Des carres et des ronds, published in Paris in 1974. Although the visual codes used by the two artists are quite similar, the works themselves are very different. Ache's books have a very conventional picturebook format and the visual retelling is supported by a verbal narrative. The tale is told briefly on the verso in both Japanese and French, while the illustrations appear on the recto. The illustrations also have captions that echo an important line from the text on the facing page.