What’s the Big Deal About Decentralization?

It’s impossible to understand blockchain technology or to fully appreciate its potential impact without coming to grips with the concept of decentralization. The idea is wrapped up in the nature of the technology itself. They are as inseparable as sunlight and solar energy, or a stream and flowing water. In other words, one springs from the other.

Modern humans have no experience that can easily translate decentralization into something comprehensible because we’ve been so entrenched in the centralized command and control operations that have dominated Western civilization for millennia.

Nevertheless, decentralization is not new. Biblical scholars are familiar with the structure of a small nation of Hebrews before they insisted on installing a king. Israel was a nation governed by 12 tribes. Each tribe colonized a specific geographic region within the land of Canaan. From each tribe arose a series of judges who served as leaders during times of crisis. There was no central government.

As far as blockchains are concerned, the features all run together. Immutability, decentralization, enhanced security, distributed ledger, faster payments, consensus, increased computing capacity, peer-to-peer interaction, and minting all go hand in hand. While some blockchains may not have all nine of these characteristics, the first six are essential. Remove any one of them and you don’t have a blockchain. Each of the features are part and parcel of the whole package. And the benefits flow from them.

Decentralized social media attempts to take this package and apply it to one use case that gives users more control over their identities, greater account security, and the ability to monetize their own content without fear of censorship or retaliation by some centralized overlord.

The Modern Internet’s Power Structure Is Centralized

Decentralization is sharing control over all the resources on a network. It means that no one individual or group of individuals makes all the decisions. Since everyone can participate, everyone can benefit to the degree that they participate in the ongoing operations of the network.

There’s decentralized finance, decentralized file storage, decentralized gaming, decentralized marketplaces, decentralized organizations, and decentralized computing. So why not decentralized social media?

This may come as a surprise to some people, but the Internet started as a decentralized network that has since strayed from its decentralized roots.

In its infrastructure and architecture, the Internet is still decentralized. No one owns or controls the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP), File Transfer Protocol (FTP), or Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), which are the basic building blocks of the Internet. However, several large organizations do exert a certain amount of control over the Web and how it is used. For instance, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers is the nonprofit entity that controls the issuance of domain names, the approval for generic top-level domains (TLDs), and country code TLDs. Google controls which websites rise to the top of its search results. And Wikipedia editors decide what content makes it into the Web’s clumsiest encyclopedia.

In November 2020, Google owned 69.80 percent of the search market on desktop computers and a whopping 93.96 percent of mobile searches.1 By the same token, 3.21 billion people used at least one of Facebook’s core products (Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, or Messenger) each month in the third quarter of 2020.2 In September 2019, 150.6 million mobile users shopped from Amazon’s mobile app, almost twice as many that used the second most popular e-commerce shopping app, Walmart.3

These are startling statistics considering there are almost 2 billion websites4 today. Let’s take a quick look at the development of the Internet so we can see how it became so centralized.

Where Did the Internet Come From?

In the 1930s, a man named Alan Turing came up with the concept of a digital computing machine, a primitive scanner.5 By 1941, there was a functional working model. During World War II, Turing and another cryptanalyst working for the Government Code and Cypher School in Bletchley Park, UK created a digital computer called The Colossus. It was used to intercept and decrypt German communications.

In 1945, the United States built its first digital computer, a device called ENIAC, an acronym for Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, to calculate artillery tables.

Over the years, digital computing research continued and machines grew in size, function, and speed. In 1952, IBM created the first mass-produced electronic computer, ushering in the age of business computing. The IBM 701 became the favored computer of U.S. defense department scientists because of its ability to run fast computations.

As America’s, and the world’s, reliance on computers grew, there were soon thousands of national and global businesses, colleges and universities, and government agencies using them to handle daily business, defense, and scientific tasks. Many of these entities worked closely together on business and government initiatives, but their computers couldn’t talk to each other. A need arose to network them together so that key people working on projects in different geographical locations, sometimes with hundreds or thousands of miles between them, could more efficiently get work done.

Development of the ARPANET

By the mid-1960s, wide area networks (WANs) were the norm. A Department of Defense agency called Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) saw a huge benefit to the military having its own WAN and, in 1962, commissioned what would become the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET).

The ARPANET relied upon two recently developed pieces of technology that would later become essential elements of the Internet. Packet switching and the TCP/IP protocol allowed defense department and university research computers anywhere in the world to share information over a WAN for military and national defense purposes. The ARPANET also had one other feature that was instrumental in maintaining a technological lead during the Cold War. It was decentralized.

ARPANET connectivity saw its consummation in 1969 and the defense department’s network program officially launched a year later. In 1975, Congress created the Defense Communications Agency, which took control over the ARPANET.

While there was a central office managing the defense asset, the computers on the network had no hierarchy. All the computers were considered equal on the network and had equal access to the network. This distributed nature of the network was considered a benefit because it was a defense against any potential communications attack. If one node on the network was taken down by any kind of attack, the other nodes would all pick up the slack and there’d be no break in communications. This was during the height of the Cold War, so it was a very real threat.

Because ARPANET was a government-owned asset, its use was restricted to noncommercial activities. That’s why it was widely used by government agencies and university research teams. Over time, however, its expansion included major corporations that were involved in research and defense contracting. Some government agencies developed their own WANs.

By the mid-1980s, supercomputers had taken over several government agencies, personal computers had become a regular in many U.S. homes, and public–private partnerships had been created to network computers in state and local governments, nonprofit organizations, and private enterprises.

It would be misleading to suggest that the major developments toward a worldwide Internet all took place in the United States and Great Britain. The truth is, by the late 1980s, every major country around the world had their own networks. In some cases, they had networks of networks where independent WANs were connected to each other through TCP/IP protocols and packet switching technology.6

It had already become clear to major users of these networks on both sides of the Atlantic that linking their networks together would provide a mutual benefit. The United States had been discussing this with the UK and other European countries since the 1970s.7

Essentially, the Internet is an international network of networks. It pulls together independently developed WANs in various countries around the world that use the same underlying technologies of packet switching and TCP/IP.

What Was the Usenet?

In 1979, a couple of Duke University students came up with a brilliant idea for academics and researchers at universities.8 These students envisioned a worldwide decentralized bulletin board system. By establishing connections between computer nodes all around the world, anyone would be able to enter into the newsgroup or discussion group of choice and have a textual conversation with another person interested in the same topic. And there would be no one—no company or corporation, no government, no king or president, and no central authority—who could stop it.

This system was the Usenet, a shorter phrase that stands for user network.

The Usenet system was revolutionary for a few reasons. First, it predated the Internet. Second, it was created in the days before digital subscriber lines (DSLs), high-speed Internet connection systems that are a necessary component for today’s highly digitized Web. Before DSL, all that computer systems had for connecting to each other was a dial-up service utilizing a modem and a router. It was really all that was necessary for the primitive technology of Usenet, which brings me to the third reason the Usenet system was so revolutionary. It was centered on delivering ASCII text messages that did not rely on graphical content, so it was essentially like e-mail but with a one-sender-to-many-recipients component.

Another thing the Usenet gave us is the language of the Internet. Much of the modern Internet lingo is a holdover from the Usenet days. Many Usenet terms9 have been added to the dictionary:

• FAQ (frequently asked questions)

• Spam

• Flaming

• Sockpuppet

• Lurker

• Troll

Usenet groups typically came in two kinds. There were moderated newsgroups and unmoderated groups. A newsgroup moderator would receive all incoming messages and approve them before they could be published to the newsgroup. Unmoderated newsgroups posted messages from members automatically with no approval agent. In the days before the Internet when Usenet newsgroups were popular, most newsgroups were unmoderated.

Due to the limitations of primitive computing and networking technology, newsgroups were typically limited in their storage capacity. Therefore, messages had to be kept small, so many newsgroups limited the size of messages.

It didn’t take long for the Usenet and the ARPANET to marry, allowing users of both systems to interact together side by side. Over time, however, the Usenet fell out of fashion. This happened for a number of reasons. There were legal issues related to copyright infringement, particularly in many unmoderated newsgroups. There was also a criminal element that would use newsgroups to distribute child pornography and facilitate other illegal activities. On top of that, advancements in technology and the genesis of the Internet with developments in online bulletin boards and Internet forums made the Usenet no longer relevant.

Communications Protocols

Just like humans, in order for computers to communicate with each other, they need to understand the same language. The language of computers on a network is called a protocol. The modern Internet runs on three primary networking protocols—TCP/IP, FTP, and SMTP.

TCP/IP was created in the 1970s by two men associated with DARPA. Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn met at the University of California, Los Angeles. Initially, they created the Transmission Control Program (TCP) based on the packet switching network of CYCLADES,10 a French alternative to the ARPANET.

The IP part of TCP/IP developed separately, but Cerf and Kahn combined them in 1975 to facilitate the connection of almost any computer in the world to the ARPANET. Their work together combined the technology of packet switching, the file sharing process that today’s routers use to deliver information from one computer to another over the Internet, and TCP/IP technology. By combining these two developments, they essentially created the underlying foundation for the Internet.

FTP was created in 1971 by a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

FTP is significant because it is the file transfer format used to send data files between a client and a server on a computer network. It’s the format used by website developers and designers when they create a website and publish it to the World Wide Web. In Internet technology, the client is the individual computer that accesses information on a server. The server is the computer or program that provides functionality for the client to use while accessing the Internet.

Before TCP/IP, there was another networking protocol called Network Control Program (NCP), which facilitated the ARPANET. Initially, FTP ran on NCP. In 1980, that changed and FTP started running on TCP/IP.11 This was a necessary development for the future World Wide Web in order for users on the network to create and publish websites.

If you’ve used e-mail, then you’re familiar with SMTP.

SMTP was first developed in 1982. Several key people were significant to the mail transfer protocol coming to fruition. It was necessary because sending electronic mail over the ARPANET prior to SMTP was somewhat clunky. At that time, the delivery of electronic mail was more efficient when both computers were not connected to the network at the same time.

There are other e-mail network protocols that are used today, but SMTP is the most efficient for sending and receiving e-mail when the sender and receiver are both connected to the World Wide Web at the same time.

By 1985, the Domain Name System (DNS) and Uniform Resource Locator (URL) system we use today had been created. The DNS is like a phone book for the computers connected to the Internet. It translates human-created computer host names into IP addresses so that computers on the network can identify each other more efficiently. Unfortunately, DNS names are difficult for humans to memorize, so the URL system translates IP addresses into website addresses within browsers to make the Internet easier for people to use. With these two developments, the Internet was primed to make its transition into the commercial behemoth we now know as the World Wide Web.

The Development of the World Wide Web

Having a technical understanding of each of these foundational Internet technologies is not necessary to use the World Wide Web, or blockchain technology. However, understanding how these technologies developed does give users a better understanding of the evolution of computing in general and computer networking specifically. If you use the Internet, you are connected to a massive worldwide computer network. Blockchains are extensions of that network.

Before we get to the big idea—decentralization and why it’s important—let’s first delve into the development of the World Wide Web and how it went from being decentralized to being centralized.

The man responsible for creating the World Wide Web is an English computer scientist named Tim Berners-Lee. He developed what is called hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP), the communications protocol World Wide Web resources use to send and receive information over the Web. This information includes e-mail, website content, links between websites, audiovisual content, cookies, and more.

Berners-Lee was a researcher at the European Council for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Geneva, Switzerland when he published a proposal designed to persuade CERN management to allow him to create a hyperlinked information management resource called Mesh.12 (Figure 2.1) That was in March 1989. He created the first Web browser, called WorldWideWeb, in 1990.13 He used his browser, which was also an HTML editor, to publish the first website in August 1991.

Figure 2.1 The basic architecture of the Internet is decentralized, allowing Web browsers from anywhere in the world to access the Internet through various servers as well as information stored on servers, which are also located all over the world

Credit: Taylored Content (recreated from a diagram included in tim Berners-lee’s original proposal

From the beginning, it’s clear that Berners-Lee intended the creation of the WorldWideWeb to be for CERN’s internal use, and he intended it to be decentralized.14 He wrote, “To be a practical system in the CERN environment, there are a number of clear practical requirements.” They included:

• Remote access across networks

• Heterogeneity (access from different types of systems)

• “Non-centralisation”—In his own words, “Information systems start small and grow. They also start isolated and then merge. A new system must allow existing systems to be linked together without requiring any central control or coordination.” (emphasis mine)

• Access to existing data

• The ability to add private links to and from public information as well as annotate links privately

• Addition of graphics at a later date

• Data analysis

• Live links

That list summarizes the concept of the World Wide Web in the mind of its creator, and it’s the vision that Satoshi Nakamoto had when he created bitcoin and the world’s first blockchain. Around that idea of a decentralized digital currency, an entire ecosystem of cryptocurrencies have arisen attempting to achieve the same end goal and blockchain developers all over the world are working toward that end.

In case there is still a bit of skepticism in your mind, Berners-Lee wrote an essay in 2015 describing how he came upon the idea for the World Wide Web, which he initially called Enquire, and the process he went through to create it. He used the word “decentralized” twice in that document. The first instance was on page 1, where he wrote:

What that first bit of Enquire code led me to was something much larger, a vision encompassing the decentralized, organic growth of ideas, technology, and society.15

The second time he used the word “decentralized” was on page 16, where he wrote:

The system had to have one other fundamental property: It had to be completely decentralized. That would be the only way a new person somewhere could start to use it without asking for access from anyone else. And that would be the only way the system could scale, so that as more people used it, it wouldn’t get bogged down. This was good Internet-style engineering, but most systems still depended on some central node to which everything had to be connected-and whose capacity eventually limited the growth of the system as a whole. I wanted the act of adding a new link to be trivial; if it was, then a web of links could spread evenly across the globe.16

Berners-Lee went on to write, “So long as I didn’t introduce some central link database, everything would scale nicely …. Hypertext would be most powerful if it could conceivably point to absolutely anything …. Every node, every document … would be fundamentally equivalent …. Each would have an address …. They would all exist together in the same space—the information space.”

Hyperspace.

It’s a fact that Berners-Lee’s vision and Nakamoto’s vision were similar in the sense that they both encompassed the quality of decentralization as fundamental to their creations. But if we look at the World Wide Web today, is it decentralized? In many ways, it isn’t. Let’s take a look and see why.

The Wild and Wicked 1990s

It didn’t take long for the World Wide Web to take off. Berners-Lee published the first website in August 1991. One year later, there were just 10 websites published.17 In mid-1993, there were 130, representing 1,300 percent growth. But the biggest growth year in history for the World Wide Web was from June 1993 to June 1994 when there were 2,738 websites, according to data compiled by NetCraft and Internet Live Stats. In that same year, the number of World Wide Web users jumped from just over 14 million to more than 25 million.18

In order for the Web to scale, users would need a browser. Between 1991 and 1993, several different browsers competed for early dominance. Most were based on the UNIX operating system, which made them impractical for everyday users because most personal computers operated on OS or Windows.

Another drawback to some of the early browsers was that they weren’t graphical. That made them cumbersome for people accessing the Internet from home on their early Windows-based personal computers. In September 1993, a browser called Mosaic made the World Wide Web practical for everyday use by people other than research scientists, business executives, and university professors.19 It fueled the growth of the Internet.

In 1994, the leader of the Mosaic development team, Marc Andreessen, left the company to start Netscape. In October, Netscape launched the Navigator browser, which grew to be very popular.

1994 was a pivotal year for the World Wide Web in another way. Yahoo! launched that year under the name Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web. It served one purpose: To catalog websites. It was the world’s first website directory. Named for its two founders, Jerry Yang and David Filo, it was one of the first attempts to create a centralized online database. By the end of 1994, there were more than 10,000 websites published.20

Prior to the first website directory, there were two attempts to create a search engine for indexing websites. The first was a website called JumpStation, which utilized the first Web crawler, or robot, to crawl the Internet and index Web pages—much like Google does today.21 However, due to funding issues, the site was dead within a year.

The other project was more successful and more decentralized. ALIWEB, an acronym that stands for Archie-Like Indexing for the WEB, was announced in late 1993 but launched in 1994.22 The tool was designed so that information indexed in the database could be retrieved from multiple different Archie servers and was collected through an anonymous FTP protocol.23 This set up maintained the Internet’s initial decentralization feature and the central feature of anonymity that some blockchains attempt to create through their protocols.

In 1995, the same year Amazon launched, Microsoft developed its browser Internet Explorer, which threw a knuckleburger right into the face of Netscape Navigator and thus enflamed the famous browser war of the late 1990s.

A writer for Network World described the start of the browser war as something akin to a college fraternity prank. He wrote:

Late on the night of September 30, 1997, a group of Microsoft employees strategically placed a large metal likeness of the Internet Explorer logo on the front lawn at Netscape Communications in Mountain View, California—a signal that the browser war was fully ignited.24

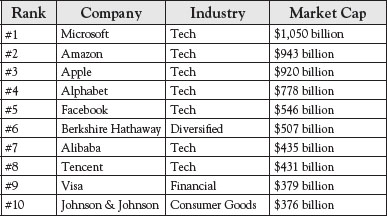

At the time, Netscape Navigator had 72 percent of the browser market. Microsoft was on its fourth iteration of Internet Explorer. When Netscape wanted to release a version of its browser for Windows 95, Microsoft tried to discourage it and the U.S. Department of Justice sued.25 Eventually, Microsoft won the first battle in the browser war, but it was a long fight that pitted the world’s largest company at the time26 (Figure 2.2) with an upstart that was winning in one small part of Microsoft’s overall business.

Figure 2.2 In 1999, Microsoft was the largest company in the world with a market cap of more than 583 billion. In 2019, as depicted here, it was still No. 1 with a market cap over $1,000 billion

Credit: Taylored Content. Based on data provided by VisualCapitalist.com

As Netscape and Microsoft duked it out for dominance, a small company called AltaVista launched in 1995 using a Web crawler and quickly became the world’s most popular search engine. Where JumpStation failed, AltaVista succeeded in using a software program to index websites without user-submitted data. Yahoo! bought the company in 2003 and shut it down in 2013. By that time, Google had become the world’s leading search engine.

Google launched in 1998. Revolutionizing information retrieval by improving upon Web crawler technology, the company is singlehandedly responsible for birthing an entire industry of search engine marketers.

When Google entered the scene, there were already a handful of search engines competing to knock AltaVista off the throne. Most of them relied on a primitive search model based on keyword indexing, a holdover from the Usenet days. However, Larry Page and Sergey Brin based their search algorithm on the number and quality of backlinks from other Web pages. It proved to be a good move. By the end of its launch year, the search engine had 60 million Web pages indexed and was considered by at least one Internet journalist to offer the best search results of them all.27

Google arrived just in time. PayPal launched a year later, providing millions of eager Internet citizens a way to move money online, make online payments, and run online businesses more efficiently.

As Microsoft and Netscape competed for dominance in the browser market, investors went crazy throwing money at any Web-based business that moved. Interest rates were low, the economy was booming, and dot-com companies were spending money left and right. Many of them operated on net losses, hopeful that the future was as bright as their ideas. In fact, Amazon went six years before realizing a profit even though founder Jeff Bezos had planned on going eight.28 In the year 2000, the bubble burst.

What caused the crash is beyond the purview of this book, but it’s needless to say there was a heightened level of irrational exuberance as optimistic venture capitalists gambled on technology they didn’t understand. The optimism sprung from the enthusiasm that the World Wide Web was the greatest invention since the printing press. As great as it is, a business still needs a sound model and a solid financial strategy. Many Internet businesses didn’t.

The World Wide Web had grown to over 3 million websites by the end of 1999. Almost 300 million users were logging on. It could only go up from there, right?

It did, actually. One year later, there were more than 17 million websites and more than 400 million World Wide Web users.29 Still, the bubble burst and thousands of Internet businesses went down. Among the survivors were eBay, Google, PayPal, Yahoo!, and then-unprofitable Amazon. All of them would rise to be among the largest companies on the planet today. Each of these young companies went on to become some of the most revered and reviled companies in the world as younger generations came of age and introduced their own ideas. What contributed to the success of each company is a vision and a centralized approach to business that made them efficient and effective at positioning themselves in front of a market craving their product.

The next two decades would give rise to a new suite of centralized Internet behemoths, some of them social media companies. YouTube is the second largest search engine and the largest video sharing site, but it is also owned by Google. Facebook is the largest social media company that seems to continuously slosh around in the mosh pit of controversy as its profits escalate. One can’t help but wonder, where do we go from here?

Why Isn’t the Web Decentralized?

When Ralph broke the Internet, we all laughed, but today the Internet is broken and it’s no laughing matter. Ralph has become a fitting and startling metaphor for Big Tech. George Orwell taught us to fear Big Brother, but no one thought it was going to be corporations that gave us Newspeak.

Nevertheless, the largest companies on the planet today have set themselves up as either partners or rivals to the largest governments. In late 2020 and early 2021, people left Facebook and Twitter in droves to protest against the platforms’ “censorship” of then-President Donald Trump. Most of them were Trump supporters, but even people who do not like his politics, his policies, and his personality opposed the censorship.30 What happened to the Internet? Why did it fall from its original grace as a decentralized tool of communication to its current state of power centralized in the hands of a few? Better yet, what can we do to fix it?

As Sir Berners-Lee noted, the natural tendency for systems is to merge. Thomas Jefferson said something similar. “The natural progress of things is for liberty to yield and government to gain ground,” said the author of the Declaration of Independence. If he were alive today, I think the third president of the United States would be appalled that some of the biggest threats to liberty are coming from private citizens.

Since the early 1980s, Internet users have argued over a concept called net neutrality. As early as 1994, in the early days of broadband, Senator Al Gore expressed concerns about ensuring fair treatment and equal opportunity for everyone on the World Wide Web.31 Few people then understood what he was talking about.

Gore has had a reputation throughout his political career as being wooden and high-minded. Truthfully, he’s not very inspiring, but his insights into the workings of the Internet have largely been underestimated and misunderstood. He was well ahead of most people in the early 1990s and foresaw how Internet Service Providers (ISPs), in particular, could make it difficult for certain classes of people or specific types of content to be treated fairly. While he had no specific solutions to offer, he at least saw the problem.

In 2004, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) established a set of guidelines for maintaining Internet freedom.32 It didn’t take long before the principles to be stress-tested. In 2007, the Associated Press (AP) ran an experiment and determined that Comcast was blocking some BitTorrent traffic.33

BitTorrent is a peer-to-peer file sharing service. The AP experiment involved downloading a King James Bible using BitTorrent software because “it is an uncopyrighted work.” The experiment led to a settlement in 2009 with Comcast paying class action litigants $16 million while admitting no wrongdoing.34 The FCC had already ruled against Comcast in August 2008 declaring the company had illegally throttled the bandwidth of some of its customers.

The FCC faced its own set of problems in 2013 when a federal court ruled it had no authority to enforce net neutrality rules because ISPs were not classified as common carriers under the Communications Act of 1934.35

This setback sent the FCC back to the drawing board. A proposal was published for new rules that would allow the FCC to enforce net neutrality without violating the court order.36 Essentially, these new rules included a plan for an “Internet fast lane” where some content—mostly content from large corporations—could be given preferential treatment while everyone else used the slow lane. Big Tech came unglued. More than 100 Internet companies, including Google, Microsoft, eBay, and Facebook sent a letter to the FCC chairman opposing the rules.37

Despite Big Tech’s concerns about what they considered a “grave threat to the internet,” the FCC passed the new rules in a 3 to 2 vote. Internet companies formed a protest and purposely slowed down their services on September 10, 2014 to show what the Internet would look like under the new rules. Participating websites included Twitter, Reddit, Netflix, Vimeo, Kickstarter, Tumblr, and many more.38 A month later, then-President Barack Obama asked the FCC to classify broadband as a telecommunications service in order to preserve net neutrality. Future president Donald Trump tweeted, “Obama’s attack on the Internet is another top-down power grab. Net neutrality is the Fairness Doctrine. Will target conservative media.39”

Throughout the first three months of 2015, Republicans and Democrats in Congress argued over net neutrality. In March, the final rules were published.40

Predictably, several ISPs took it to court. A three-judge panel ruled in favor of the FCC, maintaining the idea that ISPs are public utilities.

In 2017, shortly after taking office, then-President Donald Trump appointed Ajit Pai, a vocal opponent of net neutrality, to chair the FCC. Pai set out immediately to repeal net neutrality. After a long fight, a public comment period, and some nasty politics, the repeal was finalized on June 11, 2018.41 However, that did not mean the fight was over and the matter settled. Several states created their own rules for net neutrality with President Trump’s criticism attached.

The battle over net neutrality has largely been a partisan bicker. Democrats favor net neutrality. Republicans want freedom for big corporations to do as they please, which often means running roughshod over smaller businesses and consumers. Both sides have good talking points and neither trusts the other. But when you have one large monolothic centralized agency—be it a government, corporation, or something else—fighting with another over a public asset, the big loser will always be those who can’t fight for themselves. In this case, that means the average Internet user.

The old adage “money talks” is apropos, too. Both sides are funded by big moneyed interests. In the end, those without the money to fight for themselves are left with the table scraps of those who can.

Has Centralization Failed Us?

Centralization is nothing new. In a sense, some form of centralization has been with us for most of human history. Ancient Sumeria, at least 6,000 years ago, had organized itself into city-states with functioning infrastructure and a code of laws. It’s likely there were earlier civilizations with similar centralized structures.

In many ways, centralization is good. Who can argue that roads and bridges are a bad thing, particularly when so much of modern commerce relies on them for the transport of goods so that consumers can purchase them and put them to use? When a crime is committed, police officers can respond to the event and arrest those responsible. On the other hand, what can be used for good can also be abused.

The U.S. Declaration of Independence was written in response to perceived abuses of the King of England upon the colonists in North America. In 1953, the U.S. Army ran biological and chemical weapons tests on personnel who were not informed of the tests and did not volunteer. In 2004, the Abu Ghraib prison abuse scandal involved U.S. military and civilian contractors who had humiliated enemy prisoners of war at the detention camp. These are just a few examples.

Throughout human history, governments have overstepped their authority and, at times, become downright abusive. The 20th century is full of tales of authoritarian regimes that have been brutal, from the Red Terror to the Nazi concentration camps.

Abuse doesn’t always come from the hands of government either. Corporations and private individuals have been known to get aggressive or become negligent. In March 1989, oil tanker Exxon Valdez spilled more than 10 million gallons of crude oil into Prince William Sound doing damage to marine life. Michael Milken is a noted financier known for selling junk bonds and violating U.S. securities laws during the 1980s.

Early in 2021, stock investing app Robinhood halted trading on GameStop stock when a group of Reddit users collaborated on buying up shares to drive up prices.42 It infuriated some users, including popular YouTuber Philip DeFranco, who pulled his money out of Robinhood and stopped showing Robinhood ads to his audience.43 DeFranco, a long-time supporter of bitcoin, is now a supporter of a cryptocurrency that competes with YouTube.44

Libertarians of various stripes, the cypherpunks, radicals on the left and right, and blockchain enthusiasts will often point to these abuses as evidence that centralization is bad, evil, or untrustworthy. They have a point. Human nature has a dark side.

The question is whether decentralization can or will solve any of these issues. Die-hard blockchain enthusiasts swear by the technology, claiming it will solve the issues and make trust between humans unnecessary and obsolete. But the conundrum is that all technology comes from the mind of man, which means it bears his mark—untrustworthy, imperfect, and fallible. This is where a healthy skepticism can save the day.

Nevertheless, there’s something to be said for decentralization. When centralized hedge fund billionaires shorted Gamestop stock 150 percent, it was a decentralized group of smaller investors who combined their power to fight back, driving the stock price up again. The reason the Robinhood incident is so irksome is because it’s another example of centralization beating down the little guy. That’s why crypto enthusiasts are willing to cede control to the code.

The “trustlessness” of the technology is a feature that means everyone on the network is treated the same no matter who they are, how much wealth they have, or what their name is. Whether that can be achieved or not is what the fuss is about.

How Blockchain Promises to Fix the Centralization Problem

Jack Dorsey, cofounder and former CEO of Twitter, believes he shouldn’t have had the power to banish people from his platform, even though he used that power against a sitting president. He said such bans could “erode a free and open global internet.45”

Dorsey is also the CEO and founder of payments company Block (formerly Square) and an investor in bitcoin. Decentralization is clearly on his radar.

In 2019, Twitter announced that it was funding research into a decentralized social network called Bluesky.46 What makes the announcement so interesting is that one of the largest centralized social networks is experimenting with decentralization. That not only says a lot about Twitter, but it says a lot about the current state of the Internet. It has become a collage of walled gardens.

The conversation on decentralizing the Web has much to do with the difference between protocols and platforms. TCP/IP is a protocol. No one owns it. No one controls it. Facebook and Twitter, on the other hand, are platforms and we all know who controls them.

Blockchains also have protocols. Some of the popular blockchain protocols include Bitcoin, Ethereum, Ripple, EOS, Litecoin, and Polkadot.

A blockchain is a secure method for storing data. A protocol is a set of rules or guidelines that govern how that data is communicated. If no one owns it and no one controls it, then no one can stop anyone else from building on top of it. Once an application has been built, no one can take it down. This is the concept behind Unstoppable Domains, a company that sells blockchain domain names that allow people to synchronize all of their crypto wallets into a single address that bears the owner’s name. Each domain name is a private key. If that private key is secure, whoever controls it controls the domain name and no one can unpublish it, delete it, remove it, ban it, confiscate it, or hide it.47 Of course, browsers can always stop people from seeing a website or domain name, but since end users can choose which browser they use, that should not be a problem for anyone ready for a decentralized Internet.48

Whoever controls the platform controls the content. Facebook controls everything within its domain through algorithms and human editors. Twitter controls all the content within its domain. Google controls which websites rise to the top of its search queries and which ads are displayed. Amazon essentially controls the online retail industry.

Legacy social media will always be beholden to advertisers. Anything deemed a threat to advertiser interest is subject to editing, blocking, deletion, and deplatforming. People can lose their means of income just by running afoul of policies they didn’t agree to when they joined a platform.

Blockchain technology threatens to turn this reality on its head by reverting the Internet back to its decentralized nature through the implementation of competing and cooperating protocols. And social media can be a part of that.

While the technological infrastructure of the modern Internet is still decentralized, power on the Internet is centralized in the hands of a few large corporations and the people who control them. The early Internet was decentralized in its infrastructure as well as its power structure. To return to that state of technological bliss, the core technology of the Internet is in dire need of enhancement. That’s what the blockchain revolution is all about.

When social media platforms can demonetize and deplatform users for any reason, it’s imperative to reclaim the benefits of decentralization. Recent events have proven that to be true.

The leading authority figures of legacy social media agree they have too much power. Even as they overextend their reach and exploit their own users, they plan their own move to decentralized protocols and scheme to launch their own cryptocurrencies.

Decentralization promises the same benefits to everyone. Once again, it may not be prudent for every use case, but anyone who cares about the future of freedom should embrace decentralization in at least some use cases.

1 “Search Engine Market Share,” November 2019-February 2021. NetMarketShare, www.netmarketshare.com/search-engine-market-share.aspx (accessed March 31, 2021).

2 Tankovska, H. February 02, 2021. “Cumulative Number of Monthly Face-book Product Users as of Fourth Quarter 2020.” Statista, www.statista.com/statistics/947869/facebook-product-mau/ (accessed March 31, 2021).

3 Statista Research Department. February 04, 2021. “Most Popular Mobile Shopping Apps in the United States as of September 2019, by Monthly Users,” Statista, www.statista.com/statistics/579718/most-popular-us-shopping-apps-ranked-by-audience/ (accessed March 31, 2021).

4 “Total Number of Websites,” Internet Live Stats, www.internetlivestats.com/total-number-of-websites/ (accessed March 31, 2021).

5 December 18, 2000. “The Universal Turing Machine,” The Modern History of Computing, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/computing-history/#UTM (accessed March 31, 2021).

6 R. Hauben. 2004. “The Internet: On Its International Origins and Collaborative Vision (A Work in Progress),” AIS.org. www.ais.org/~jrh/acn/ACn12-2.a03.txt (accessed December 29, 2020).

7 Ibid.

8 “History of Usenet,” Usenet Reviewz, https://usenetreviewz.com/history-of-usenet/ (accessed January 04, 2021).

9 “Usenet Newsgroups Terms Defined,” Newsdemon, www.newsdemon.com/usenet-terms.php (accessed January 04, 2021).

10 “TCP/IP,” History-Computer.com. https://history-computer.com/Internet/Maturing/TCPIP.html (accessed January 04, 2021).

11 C.M. Kozierok. 2005. “FTP Overview, History and Standards,” The TCP/IP Guide, www.tcpipguide.com/free/t_FTPOverviewHistoryandStandards.htm (accessed January 04, 2021).

12 T. Berners-Lee. 1989. “Information Management: A Proposal,” W3.org, https://web.archive.org/web/20090315161300/http://www.w3.org/History/1989/proposal.html (accessed January 05, 2021).

13 J. Quittner. 1999. “Network Designer,” Time Magazine, https://web.archive.org/web/20071016213128/http://time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,990627,00.html (accessed January 04, 2021).

14 T. Berners-Lee. 1989. “Information Management: A Proposal,” W3.org, https://web.archive.org/web/20090315161300/http://www.w3.org/History/1989/proposal.html (accessed January 05, 2021).

15 T. Berners-Lee. 2015. “Enquire Within Upon Everything,” cs.wellesley.edu, https://web.archive.org/web/20151117022333/http://cs.wellesley.edu/~cs315/BOOKS/TBL12.pdf (accessed January 05, 2021).

16 Ibid.

17 “Total Number of Websites,” Internet Live Stats, www.internetlivestats.com/total-number-of-websites/ (accessed January 05, 2021).

18 Ibid.

19 R.J. Vetter, C. Spell, and C. Ward. 1994. “Mosaic and the World-Wide Web,” https://web.archive.org/web/20140824192903/http://vision.unipv.it/wdt-cim/articoli/00318591.pdf, (accessed January 05, 2021).

20 M. Gray. 1996. “Web Growth Summary,” stuff.mit.edu, https://stuff.mit.edu/people/mkgray/net/web-growth-summary.html (accessed January 05, 2021).

21 J. Miller. September 2013. “Jonathon Fletcher: Forgotten Father of the Search Engine,” BBC News, www.bbc.com/news/technology-23945326 (accessed January 05, 2021).

22 M. Koster. November 1993. “ANNOUNCEMENT: ALIWEB (Archie-Like Indexing for the WEB),” Google Groups, https://groups.google.com/g/comp.info-systems.www/c/WQO-hJwFNi8?pli=1 (accessed January 05, 2021).

23 “Your Friend Archie,” https://www2.cs.duke.edu/csl/docs/EFF_Guide/eeg_139.html (accessed January 05, 2021).

24 J. Fontana. 2007. “Microsoft IE vs. Netscape Navigator,” Network World, www.networkworld.com/article/2287919/microsoft-ie-vs--netscape-navigator.html (accessed January 10, 2021).

25 U.S. District Judge Jackson, P. Thomas. 1999. “United States of America vs. Microsoft Corporation,” The United States Department of Justice, www.justice.gov/atr/us-v-microsoft-courts-findings-fact#findings (accessed January 10, 2021).

26 J. Desjardins. 2019. “A Visual History of the Largest Companies by Market Cap (1999-Today),” Visual Capitalist, www.visualcapitalist.com/a-visual-history-of-the-largest-companies-by-market-cap-1999-today/ (accessed January 29, 2022).

27 S. Rosenberg. 1998. “Let’s Get This Straight: Yes, There is a Better Search Engine,” Salon, www.salon.com/1998/12/21/straight_44/ (accessed January 10, 2021).

28 A. Khan. 2018. “How Jeff Bezos Started Amazon.com and Became the Richest Person,” Startup Wonders, https://startupwonders.com/amazon/ (accessed January 10, 2021).

29 “Total Number of Websites,” Internet Live Stats, www.internetlivestats.com/total-number-of-websites/ (accessed November 18, 2021).

30 M. Vespa. 2020. “Why a Liberal Reporter Ripped Twitter for Censoring Trump’s Tweets … Again,” Townhall, https://townhall.com/tipsheet/mattvespa/2020/11/09/liberal-reporter-rips-twitter-for-censoring-trumps-tweets-n2579604 (accessed January 10, 2021).

31 A. Gore. 1994. “To The Superhighway Summit,” Art Context, http://artcon-text.com/calendar/1997/superhig.html (accessed January 10, 2021).

32 M.K. Powell. February 2004. “Preserving Internet Freedom: Guiding Principles for the Industry,” Federal Communications Commission (accessed January 10, 2021).

33 J. Cheng. 2007. “Evidence Mounts that Comcast is targeting BitTorrent Traffic,” Ars Technica, https://arstechnica.com/uncategorized/2007/10/evidence-mounts-that-comcast-is-targeting-bittorrent-traffic/ (accessed January 10, 2021).

34 J. Cheng. 2009. “Comcast Settles P2P Throttling Class-Action for $16 Million,” Ars Technica, https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2009/12/comcast-throws-16-million-at-p2p-throttling-settlement/ (accessed January 10, 2021).

35 September 2013. “Verizon, Appellant v. FCC, Appellee,” U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, www.cadc.uscourts.gov/internet/opinions.nsf/5DFE38F28E7CAC9185257C610074579E/$file/11-1355-1475317.pdf (accessed January 10, 2021).

36 N. Weil. 2014. “FCC will Set New Net Neutrality Rules,” Computerworld, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Net_neutrality_in_the_United_States#Early_history_1980_%E2%80%93_early_2000s (accessed January 10, 2021).

37 G. Nagash. 2014. “Amazon, Google, Facebook and Others Disagree With FCC Rules on Net Neutrality,” The Wall Street Journal, www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303701304579548364154205126 (accessed January 10, 2021).

38 J. Axelrad. 2014. “Internet Slowdown Day: Why Websites Feel Sluggish Today,” The Christian Science Monitor, www.csmonitor.com/Technology/Horizons/2014/0910/Internet-Slowdown-Day-Why-websites-feel-sluggish-today (accessed January 10, 2021).

39 M. Snider. 2016. “Net Neutrality, Beloved by Netflix, Looks Headed for the Ax Under Trump,” USA Today, www.usatoday.com/story/tech/news/2016/11/22/trump-team-appointees-indicate-net-neutrality-reversal/94266912/ (accessed January 10, 2021).

40 2015. “Protecting and Promoting the Open Internet,” Federal Register, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2015/04/13/2015-07841/protecting-and-promoting-the-open-internet (accessed January 10, 2021).

41 K. Collins. 2018. “Net Neutrality Has Officially Been Repealed. Here’s How That Could Affect You,” The New York Times, www.nytimes.com/2018/06/11/technology/net-neutrality-repeal.html (accessed January 10, 2021).

42 K.A. Smith. January 28, 2021. “Robinhood Halts GameStop Trading, Angering Lawmakers and Investors,” Forbes, www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/robin-hood-gamestop-trading/ (accessed November 18, 2021).

43 P. DeFranco. January 28, 2021. “Why This Disgusting Robinhood Dumpster Fire Has Me Furious, H3H3, Mia Khalifa, DHS Warnings, & More,” YouTube, www.youtube.com/watch?v=KfN0-OvZCp4 (accessed April 04, 2021).

44 J.E. Solsman. February 16, 2018. “YouTube Star Wants a Cryptocurrency Payday for you Every Day,” CNET, www.cnet.com/news/youtube-star-phil-defranco-cryptocurrency-props-wants-a-payday-for-you/ (accessed April 04, 2021).

45 E. Lopatto. January 13, 2021. “Jack Dorsey Defends Twitter’s Trump Ban, Then Enthuses About Bitcoin,” The Verge, www.theverge.com/2021/1/13/22230028/jack-dorsey-donald-trump-twitter-ban-moderation-bitcoin-thread (accessed April 04, 2021).

46 @Jack. December 11, 2019. “Twitter for iPhone,” https://twitter.com/jack/status/1204766078468911106 (accessed April 04, 2021).

47 M. Thibodeau. April 22, 2019. “Unstoppable Domains and the End of Internet Censorship,” HedgeTrade, https://hedgetrade.com/unstoppable-domains-ending-internet-censorship/ (accessed April 04, 2021).

48 Unstoppable Domains. March 28, 2020. “Browsers Are the Gatekeepers of the Decentralized Web,” Hackernoon, https://hackernoon.com/browsers-are-thegatekeepers-of-the-decentralized-web-i7543y1z (accessed April 04, 2021).