3

CUSTOMER-FOCUS STRATEGY 1: WIN WITH CURRENT CUSTOMERS BEFORE CHASING AFTER NEW ONES

CURRENT CUSTOMERS HAVE HIGHER revenue and profit potential than new customers. And if you meet their needs better than the competition, they’ll buy more from you. Research shows that existing customers are far more profitable than new customers—five to twenty-five times more profitable.1 New customers are expensive to acquire and typically produce less revenue once you do acquire them than satisfied current customers would. Yet, when faced with declining revenues, most companies focus on finding new customers. This is like pouring more water into a bucket with a hole in it. If your customers are draining away, fix the bucket first, or get a new one! But most companies just pour in more water.

Consider Walmart. They sell more goods and employ more people than any company in the world. They changed the retail landscape in the 1990s, but from 2012 to 2016, sales growth and profits steadily declined (see figure 9). Revenue growth declined from 6% in 2012 to −1% in 2016, while net income went from 4% to 3%. From 2017 to 2019 (estimated), revenue increased from 1% to 3%, while net income declined from 3% to 1%. Thus, while Walmart managed to grow sales, it did so at the cost of profit.

Walmart responded to dropping store revenue by cutting back on inventory and laying off workers. That made things worse: customers complained that they couldn’t find the products they wanted. The layoffs lowered morale, so employees refused to engage and answer simple questions from customers. Industry analysts routinely reported that customers were complaining about Walmart’s poor selection, long checkout lines, and bad customer service.2 Of course, some of the customers took their business to Amazon.

FIGURE 9 Walmart revenue and profit trends. Source: “Wal-Mart Stores, Inc.: Revenues and Sales,” eMarketer Retail, https://goo.gl/VqndAt.

Instead of analyzing what the real problem was and trying to fix it, Walmart decided to seek new markets in e-commerce. They blamed Amazon for their declining revenue and customer dissatisfaction. Although they did address some employee complaints and a few customer issues, they focused on expanding Walmart’s e-commerce, acquiring Jet.com in 2016 for $3 billion and buying brands such as Bonobos, ModCloth, and Moosejaw.

Walmart also introduced free two-day shipping for online orders over $35 for 2 million items, in January 2017, but unlike Amazon Prime, they didn’t charge a yearly fee. Not surprisingly, without that, this idea lost the company a lot of money. From 2017 to 2019 (estimated), Walmart did grow its online revenue as a percentage of total revenue from 3.2% to 4.7%, but profit margin declined rapidly, from 2.8% to 1.0% (see figure 10). The exact impact of Walmart’s online sales increase on profitability is difficult to decipher. Nevertheless, e-commerce has not been a positive contributor to their bottom line.

FIGURE 10 Walmart online growth relative to profitability. Source: “Wal-Mart Stores, Inc.: Revenues and Sales,” eMarketer Retail, https://goo.gl/VqndAt.

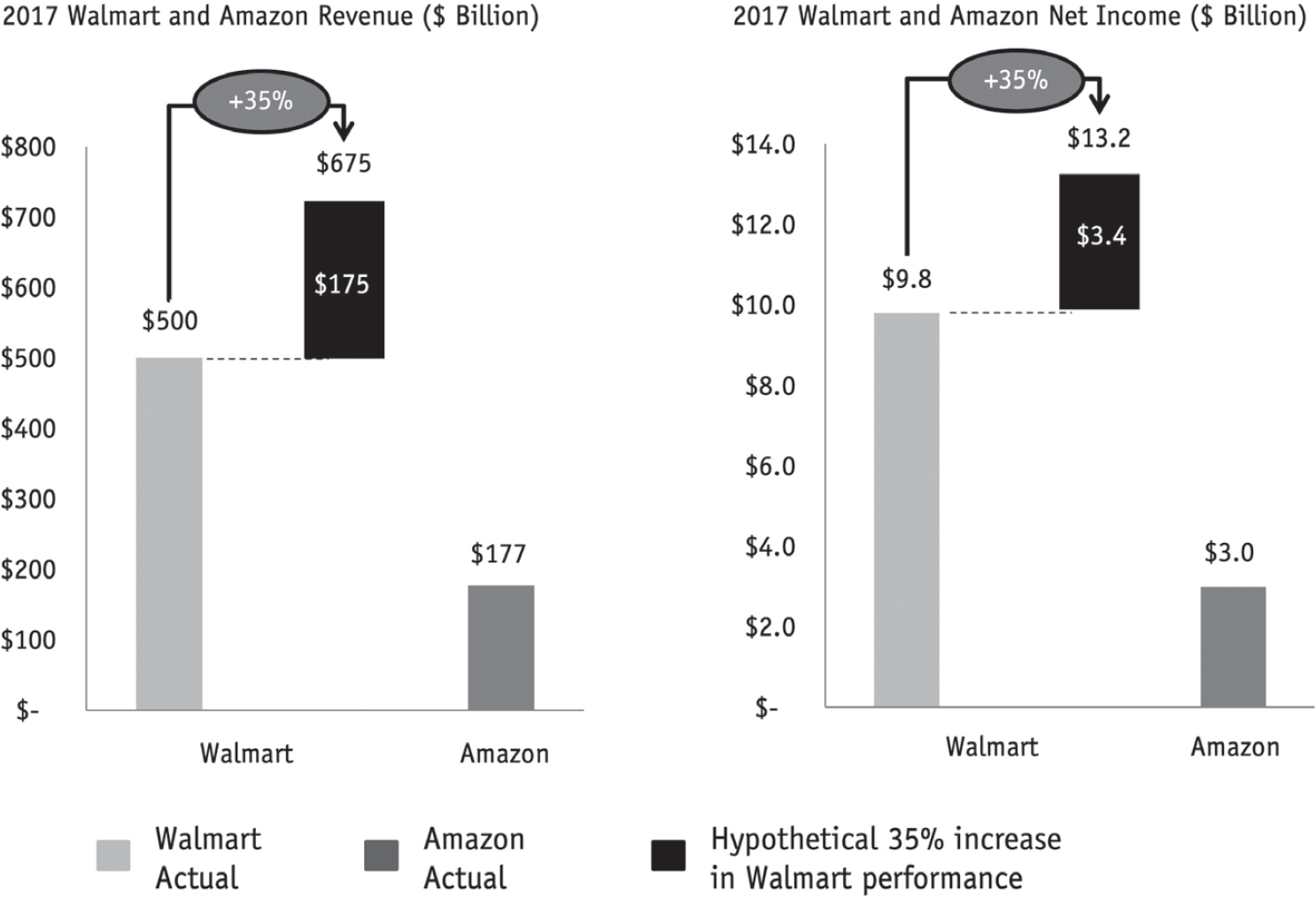

A more effective strategy would have been to focus on current customers and get them to spend more. If Walmart had done that instead of trying to copy Amazon, and if their existing customers had spent one-third more in 2017, or 35% more than they actually did, the increase would have equaled Amazon’s entire revenue and profit (see figure 11).

In 2017, Walmart’s revenue was $500 billion and its net income was $9.8 billion. Amazon’s revenue was $177 billion and its net was income $3 billion. Thus, if Walmart had grown its revenue and net income by 35%, its revenue would have increased by $175 billion and its net income by $3.4 billion—Amazon’s total revenue and profit that year.

But instead of focusing on getting current customers to spend more, Walmart focused on getting new online customers to compete with Amazon—and they did this at the cost of profitability. Amazon, meanwhile, has continued to grow.

If you’re wondering whether your company is becoming more like Walmart or more like Amazon, think about the following questions.

• How much more or less are your existing customers or customer segments spending now than they did a year ago? Two years ago?

• How have your margins changed?

FIGURE 11 Walmart and Amazon actual and hypothetical revenues and profits. Sources: Walmart 2017 Annual Report, Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., March 31, 2017, https://goo.gl/dqxrpD; 2017 Amazon Annual Report, Amazon Investor Relations, February 1, 2018, https://goo.gl/bT84eT.

If neither customer spending nor margins are growing, you need to rethink your selling activities and focus on improving your business appeal to existing customers. The steps at the end of this chapter will show you how to do that.

GETTING CURRENT CUSTOMERS TO SPEND MORE

Study after study has shown that existing customers are likely to spend more and are more profitable than new customers. As the Harvard Business Review put it, “It makes sense: you don’t have to spend time and resources going out and finding a new client—you just have to keep the one you have happy.” Bain and Company found that “return customers tend to buy more from a company over time.”3 Yet, despite this, most companies cope with declining sales by chasing after new customers.

Take Whole Foods. Their customer base increased by 27% from 2013 to 2018, but their revenue per customer dropped, and so did their profit margins, even after Amazon acquired them.4 The new customers simply did not spend as much as the old customers, and the margins on them were lower, too.

Even when businesses do focus on existing customers, most do it in old-fashioned ways that don’t increase revenue.

Loyalty Programs Don’t Work

Industries from airlines to supermarkets to rental cars have used loyalty programs for decades, promising customers that the more they spend, the more they’ll get in discounts or other perks. U.S. marketers spend an estimated $90 billion on noncash loyalty programs, but that investment increasingly appears to be wasted. Accenture found that 54% of people said they’d switched providers in the past year, and 78% say they retract loyalty faster today than they did three years ago.5 Retail, cable, bank, and home or business internet customers are most likely to switch.

But even though all this is well known, companies continue to shore up these loyalty programs. Macy’s sales dropped, forcing store closures in 2015, yet, two years later, CEO Jeff Gennette said, “We are excited about our plans for the holiday, which is when Macy’s truly shines as a gifting destination. The loyalty program, special in-store experiences, and a strong mobile and online presence will help drive holiday sales.”6 In 2017, Macy’s reworked its Star Rewards loyalty program to add e-commerce perks like free shipping offers. Though Macy’s did increase revenue by 1.3% during that holiday season, online retailers such as Wayfair and Amazon increased revenues on similar products much faster.

Companies with the highest brand loyalty do not have loyalty programs. As Dan Bane of Trader Joe’s said, “We know that loyalty does not come from a special card or a so-called ‘reward’ you receive when you spend your hard-earned dollars in a store. At Trader Joe’s, we would never test your loyalty by printing out a three-foot-long scroll of coupons for money off things the next time you shop in our stores. We reward your loyalty by pricing our products as low as they can go every single day. No coupons or club cards needed . . . ever.”7 While other grocery stores in the United States, such as Safeway and Supervalu, were closing stores, Trader Joe’s was opening new ones.

Customers don’t stick with a company because of its loyalty program. They stick with it because it meets their needs better than the competition does.

Customer Retention Programs Are Counterproductive

Other companies attempt to keep current customers by offering them incentives when they threaten to turn off service or cancel their accounts, by making it difficult for them to do it, and sometimes even by penalizing them for doing it. Punishing your customers with fines or forcing them to do something they don’t want to do is bad for business.

Cable companies like Comcast are notorious for these tactics. In November 2014, a Comcast customer decided to disconnect his service, but for several hours the customer service representative refused to disconnect the service, citing one pretext or another. When this was publicly brought to the attention of Brian Roberts, Comcast CEO, he said, “I was embarrassed by a customer service debacle with a customer trying to disconnect his service.” Then he promised to revamp the customer service department with new hires and new leadership. However, Comcast still encourages employees to force customers to buy services that they don’t need and to make it almost impossible for them to cancel their service. Comcast’s combative relationship with its customers continues, and it remains one of the most disliked companies in the United States.8 Not surprisingly, its subscriptions keep shrinking.

“Customer retention program” now has negative connotations. To most people, it means forcing current customers to jump through hoops to negotiate a fair price. Though retention programs may bolster revenue in the short term, the long-term impact on customer relationships is devastating. Not surprisingly, cable companies, the worst offenders, are suffering from cord cutting at an unprecedented rate and are desperately merging with other, profitable companies to extend their lives.

Increased Service Levels Work but Need Thoughtful Execution

The third approach companies typically take in response to falling sales is to increase service, and that has shown better results. Businesses know that they will generate more revenue if they improve service levels. Customers consider some services—warranties, faster returns, and easy credit, for instance—as almost money-back guarantees. They also tend to love having a better selection of products, free shipping, help during shopping, and easy checkout, among other things. These all provide benefits to customers other than price. However, if companies aren’t careful, the increased service levels can significantly reduce profit.

Take return policies. Most customers like lenient return policies; knowing they can easily return anything they don’t like makes them buy with greater confidence. This is particularly true when they are buying online and have never touched the product. It’s an insurance policy of sorts. Making returns easier for online purchases was what made e-commerce possible. However, returns cost retailers money. Post-Christmas returns typically cost retailers close to $300 billion, or 8% of purchases, every year. So now some retailers, including Amazon, are banning customers who return products too frequently.9 This is understandable, but it could be counterproductive for sellers.

Let’s look at what happened when Tumi tried it. Tumi’s products—luggage, bags, backpacks, and the like—were known for their durability. Some had lifetime warranties. The luggage was expensive but it had a big fan following among frequent travelers because of its durability, lifetime warranty, and Tumi’s no-questions-asked repair policy. In 2004, a private equity company bought Tumi, dropped prices to make the products attractive to more people, and decreased the famed lifetime warranty to five years. When Samsonite bought the line in 2016, they stopped honoring warranty commitments altogether. Now frequent flyers are recommending Briggs & Riley instead.10 Lowering service levels is risky!

INCREASING SERVICE LEVELS WITHOUT RUINING YOURSELF

But increasing service levels is risky, too. When the financial services market started changing, one firm’s high net worth customers asked for more support. Afraid of losing them, the firm added free personal bankers, investment specialists, 24/7 customer support, and other services. But the firm offered them to all customers and didn’t charge any of them. Not surprisingly, this ate into the firm’s profitability—so much so that they had to eliminate the popular new services. The trick, when it comes to increasing service levels, is to do it profitably. Otherwise, you will not be able to support the new service as it gains traction among your customers, and you may end up losing them when you make the inevitable cuts.

When companies give all their customers access to the same increased level of service, their costs may increase more than revenues, because a few customers end up overusing or abusing the new services levels. When customers don’t have any incentives to choose an appropriate service level, some take advantage of the company’s generosity. For example, they may return clothes even after wearing them—because they can. But there are ways around this for retailers. For example, instead of changing the return policy for everyone—even customers who never take advantage of it—retailers can ask abusers to pay return fees. Some may be willing to pay them.

Amazon has mastered the art of increasing service levels profitably. In 2005, Amazon wanted to increase its revenue and did it by identifying frequent buyers and asking them to pay for a new service: Prime. This was a financially risky move that completely changed the e-commerce industry. In those days, it took packages a week or longer to reach customers. Two-day shipping was an expensive luxury. But, as Bezos said when he started Prime, two-day shipping became “an everyday experience rather than an occasional indulgence.”11

Amazon had almost 100 million Prime members as of 2018.12 These customers are estimated to spend two to five times as much on Amazon as non-Prime members do. The fact that their shipping is “free” (many forget that they have actually already paid for it with their Prime fee) encourages them to buy more. Now, whenever Amazon offers new categories of products, Prime members automatically start buying them. Plus, customers who once would have gone to Walmart or Target when they needed something quickly now just buy it on Amazon, where prices were already lower.

With Prime, Amazon’s shipping costs increased, but the membership fees more than made up for it. Amazon balanced the cost between high- and low-volume shippers and found alternate ways to generate revenue from their customer base. There was barely any pushback when Amazon increased its Prime annual fees from $79 to $99, in 2014.

Creating Service Levels That Competitors Find Difficult to Copy

The trouble with increasing service levels is that competitors can often copy you as soon as they see you winning customers. Eventually, the new service becomes the industry standard and increases costs for everyone as competitors try to provide similar services at a lower cost, or even for free, to attract customers. Walmart copied Prime’s free two-day shipping, though Walmart had a minimum purchase requirement instead of a membership fee. Now Target and most other retailers have their own versions of two-day free shipping. For the holiday season of 2018, Target offered two-day free shipping without a minimum purchase requirement.13

The way to make money from your service levels is to make it difficult for the competition to copy you. Despite Walmart and Target introducing two-day free shipping, Amazon hasn’t lost its Prime members. The reason is simple: Prime is bigger than two-day shipping. Over time, Amazon added Amazon video, music, photo storage, and many other services to Prime, which now has a 95% renewal rate.14 As Amazon’s chief financial officer admitted, Prime members who stream video renew their membership at “considerably higher rates” than those who don’t, though these additional services have added costs for Amazon.

Amazon uses service levels well, and so do budget airlines. Traditional carriers like British Airways, Lufthansa, and others focus on business travelers, but budget airlines like Ryanair and easyJet concentrate on vacation travelers. Budget airline tickets in Europe can cost less than half the price of tickets from full-service carriers.

To do this profitably, budget airlines reduced their costs. They standardized their planes to get significant discounts from aircraft manufacturers, standardized operations, took advantage of fuel efficiency, removed unnecessary luxuries, turned around faster at gates to keep planes flying, and flew to cheaper airports. They made money by selling food on board and charging for amenities like extra luggage. Ryanair and Wizz made more money than Lufthansa, British Airways, and Air France.15 When full-service airlines tried to copy the budget airlines model, Lufthansa with Eurowings and Air France with Transavia, they failed. Though the budget airline model was simple, it was tough to replicate. Budget airlines in Europe grew year over year by 7.1%, compared to 3.5% for full-service carriers, from 2007 to 2016.

Creating a service model that competitors find difficult to copy can create a sustainable competitive advantage. Amazon’s revenue growth in the United States and the growth of budget airlines in Europe continues at a rapid pace, killing the big and mighty in their respective markets.

INCREASING REVENUE PROFITABLY

Walmart shows what a struggle it is to increase revenue profitably. Companies that do it successfully—like Amazon and the budget airlines—tailor their services to different customer segments and then convince customers to pay for those services. This compensates the companies for the increased cost of providing higher services. There are ways to segment customers in almost all industries.

Tumi, for example, could have offered its beloved lifetime warranty at an additional cost—there was no need to eliminate it completely. It could have kept its base price competitive and offered the warranty at an additional price. Instead, Tumi foolishly ended the warranty and lost its most loyal customers. And it never even asked them whether they would be willing to pay more for lifetime warranties!

Almost all companies can use the following step-by-step approach to increase service levels profitably.

• The first step is to identify customers by segment. Not all customers have the same needs, and segmenting allows you to understand what the important differences are.

• The second step is to identify the services that are valued by each of the segments. In the case of Tumi, the frequent travelers had different requirements than the casual travelers. Providing the right service to each segment is essential to ensuring they are valued.

• The third step is to create a range of services based on the different customer needs and to make them difficult for competitors to copy. Otherwise, the new service level will quickly become the industry standard and increase cost for everyone.

• The last step is to price the new service so that customers will be willing to pay for it.

The following example shows how we used these steps with a client, a leading wireless company. They needed help identifying gaps in their portfolio and developing a service model that would address them. They wanted to increase their revenue, but their customer demographic and psychographic segmentation did not show any opportunities for unique offerings.

Step 1: Identify Customer Segments

Most companies don’t do customer segmentation well. They use methods that provide psychographic and demographic insights, which may be useful for marketing and advertising but is not useful for targeting of services, because these methods don’t provide insights into buying behavior.

A better way is to segment the customer base by buying behavior that can be measured, such as usage or business metrics. This approach makes it easy to target customer segments with the service offerings valued by each.

But most companies use demographic segmentation. They segment customers by age, gender, race, and income. The assumption is that, somehow, everyone in each group will behave the same way and have the same needs. Anyone with two teenage daughters knows from experience how false this is! Some people in the same income group shop heavily online and some do not. There are early adopters of technology across all age groups, genders, and household income. Demographics are not a good way to identify people’s willingness to buy products or services.

Other companies use psychographic segmentation and divide customers into segments based on their values, attitudes, lifestyles, and personalities. The wireless company, for example, segmented customers into psychographic groups such as empty nesters, professionals, or working single parents. You can spend hours discussing the profiles and characteristics of each one of these psychographic segments, but they won’t help you predict unique service needs. A professional can be a heavy or a light wireless user. Those who travel frequently for work might use wireless data more than those who work in the office—but neither has anything to do with psychographics.

The third and least commonly used segmentation, called behavioral segmentation, is based on actual buying behavior, loyalty, usage, user status, and the like. Companies who use this method look at patterns of buying and using different products, then launch products of different sizes based on usage. For example, toothpaste is sold in different sizes in different countries according to usage patterns. Similarly, the design of loyalty programs is based on how frequently buyers purchase from a site or from stores.

Based on client work, I have found that the best way to segment customers is by business metrics such as volume/usage, profitability, or the strategic nature of the segment. For example, Amazon differentiates customers based on how much they shop online, irrespective of their lifestyle choices or demographics. A wireless company should understand the different needs of high- and low-usage customers.

For our wireless client, then, we created a survey to collect usage and purchasing behavior and other criteria from more than eight hundred respondents across the United States. For additional insight, we also used demographics to classify the respondents into four groups: mass market (people older than thirty years), youth (people younger than thirty years), business (companies with fewer than five hundred employees), and enterprise (companies with more than five hundred employees).

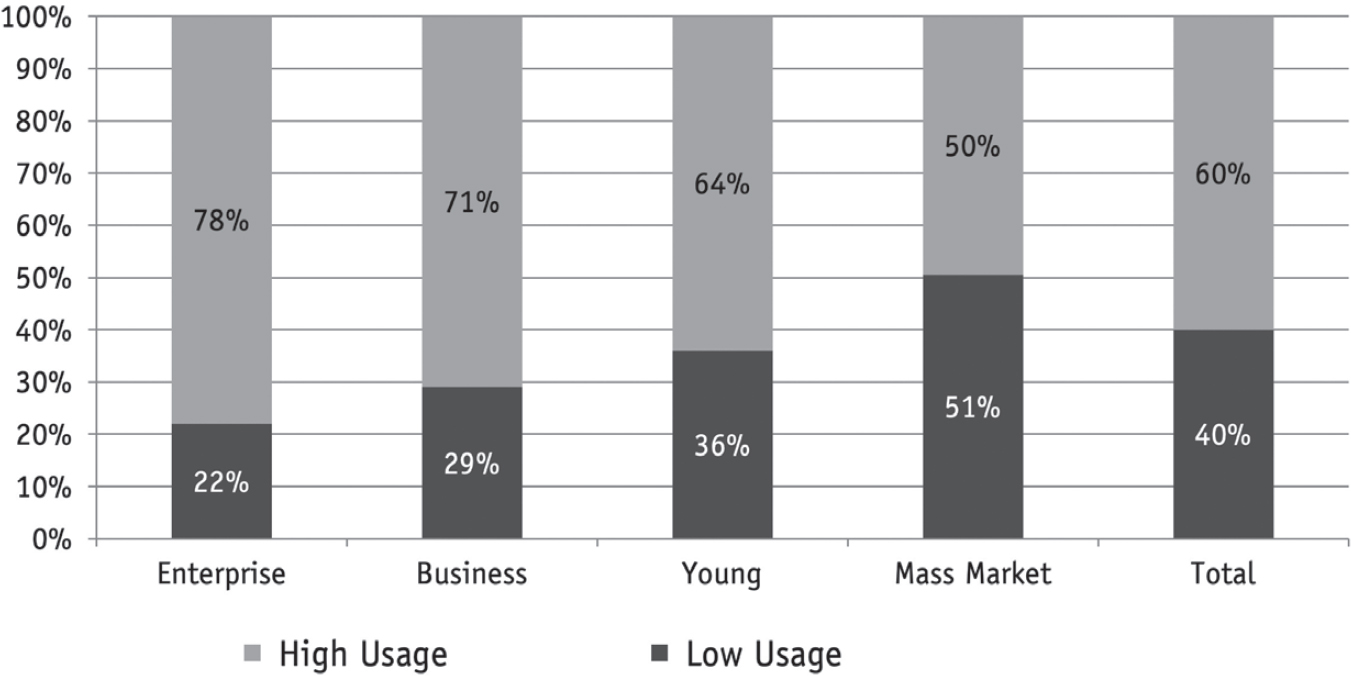

As we analyzed the data, it became clear that talk usage (minutes per month) provided more meaningful segmentation than the psychographic segmentation used by the company and the industry in general. There was a misperception that because people were on their phones all the time, everyone was using wireless services aggressively. In reality, phone usage meant far less; many people who were on their phones all the time were using Wi-Fi, because they were inside of buildings. A large number of customers were barely using wireless services, and the major wireless providers largely ignored their needs.

The heavy and light wireless (talk) users were very different. The high wireless users used more wireless data—sent more texts, used the web more, downloaded more content, and watched more videos. They valued better network connectivity over low prices. The low wireless users group used mainly voice, with some texting—only a small percentage used data. The low wireless user group was very price sensitive and switched providers frequently.

Figure 12 shows how low usage was in all segments. The low-usage group represented 22% of enterprise customers and 51% of mass market customers. On average, the low-usage group was close to 40% of the market. This group used mobile phones only when they were traveling outside the home or office. They cut across all traditional classifications, including business, youth, and mass market. From a demographics perspective, they were at all income levels, genders, races, and age groups. From an ethnicity perspective, though, the low-usage group was primarily white Caucasian as well as young Hispanic. The other ethnic groups were proportionately represented. Wireless companies consistently ignored this low-usage group and focused instead on capturing market share in the higher-usage segment by offering different data services. Yet, by doing this, they were potentially ignoring the needs of 40% of their customers, providing opportunities for low-cost entrants to disrupt the whole wireless market.

FIGURE 12 Low- and high-usage groups by classification. Source: Three S Consulting.

Step 2: Identify Services That Are Valued by Each Segment

Based on the segmentation study, we came up with four new segments to provide a more in-depth understanding of needs among the low-usage group (table 1). The exact need varied among the segments, but all of them were looking for one thing: low-cost calling and texting. They also all preferred to buy data packages, international calling, and roaming services based on specific, sometimes temporary needs—such as, for example, while traveling.

TABLE 1

Low-Usage Group Segments

Step 3: Create a Range of Services Based on Different Customer Needs

Creating a successful offering for the low-usage group required an entirely different approach than the traditional wireless model in the United States. Also, to be known for service, it was essential to develop a model that was difficult for the competition to match. Developing that kind of model is a competitive advantage when product differentiation is low, as it is for wireless service companies.

Our team studied the success of low-cost mobile models in other markets, which featured low base cost, no frills, and add-ons for which customers were willing to pay. We found that the prices had to be 30% lower than the cost of the full-service offering for it to be successful. To maintain a low cost, the company had to remove expenses wherever possible. Since handsets are a significant cost for users, we suggested that customers be allowed to use their existing handsets and not be required to sign contracts. We suggested low monthly prices with affordable add-on data plans, international calling, and roaming in Mexico.

The approach was similar to the one budget airlines use to attract cost-sensitive travelers. These airlines are successful because of their standardized planes, charges for frills, and faster operations. Budget airlines are the most profitable segment of the airline industry. We believed a budget mobile offering could become an equally profitable part of the wireless industry.

Step 4: Price the Service Appropriately So That Customers Will Be Willing to Pay for It

The critical challenge was to determine exactly how much each customer should be charged for service. This is hard to do, so companies typically use their own cost as a guide. Even then, companies lack a complete understanding of the cost of different services. A better way is to understand at what price point customers would get excited about the service, and then find a way to make it happen. It’s the approach taken by Amazon. They launch a service, lose money, learn how to make it work, and then tweak it until customers start to adopt it.

That’s the strategy we recommended to our wireless client. We warned them that it would lose money in the first few years, because of the high customer acquisition and network costs. As figure 13 shows, the client’s major expenses were customer acquisition and network operations, which cost 36% and 33% of revenue, while other costs were relatively small. So we expected the company to lose about 5% of revenue during the new program’s first few years.

To make the budget mobile offering financially viable, our plan focused on removing costs wherever possible. The plan made the offering available online, with no retail presence and no handset subsidy. The company contracted with multiple wireless providers to get preferential rates in different markets. Overhead work was outsourced. Automation was introduced to encourage automatic payments and to reduce customer support cost.

FIGURE 13 Estimated monthly revenue and cost per user. Source: Three S Consulting.

The profit, we hoped, would come from add-ons such as data plans, international calling, and roaming in Mexico. These were priced competitively and not at a discount. The assumption was that, as the company increased its subscriber base, it would be in a position to strike exclusive deals with wireless operators for the add-on services, thereby improving profitability substantially. The client launched a variant of the budget mobile offering as a prepaid service, and within a few years it was showing a profit.

Most Companies Can Profit from Following These Steps

A step-by-step approach like this can help companies to profitably increase revenue from their existing customer base. Even Amazon could learn from it. Though Amazon Prime has been wildly successful, not all of its customer segments are profitable. For instance, it’s prohibitively expensive to send one or two shipments to rural homes. So Amazon is increasing its Prime membership cost again in 2018 to compensate. But by increasing membership costs, Amazon is gambling that its profitable customers will subsidize its loss-making routes. And now, Amazon has competition for its two-day shipping from Walmart, Target, and others. Eventually, customers will probably be put off by the price increases. Wouldn’t it have been better for Amazon to develop a separate offering for rural or other unprofitable customers?

GETTING EXISTING CUSTOMERS TO SPEND MORE

Getting existing customers to spend more is the holy grail of business. Millions of customers continue to visit retail outlets, but they’re spending less than they once did. That’s the real reason for the failure of brick and mortar stores. It’s not Amazon. Companies have to find new ways to meet their customers’ needs so they’ll spend more. But they have to do it in a way that increases profitability, too. Following the process laid out in this chapter will help them to grow revenue in a financially prudent way and have a higher chance of success.

Walmart, for example, could classify its stores by volume and profitability and then provide valet and home delivery at a reasonable price in high-volume stores. Walmart could potentially introduce other services, based on customer need. Would it improve customers’ lives and would customers be willing to pay for the new services? They probably would, but we will never know unless Walmart offers them the services.