Chapter Seven

Securing Debt in an Insecure World

CREDIT CARDS AND CAPITAL MARKETS

IN 1978, DONALD AURIEMMA, then the vice-president of Chemical Bank’s personal loan department, doubted the wisdom of Citibank’s aggressive expansion into the credit card business that had begun a few years earlier. Auriemma expected that the expansion would not pay off for Citibank since he believed that “the credit card business is marginal, [and] it’ll never make big money for banks.”1 Yet within a few years, these marginal profits on credit cards would become the center of lending. By the early 1980s, credit cards metamorphosed from break-even investments to leading earners. With much higher profits than commercial loans, financial institutions began to lend as much money as they could to consumers on credit cards. By the early 1990s investments in credit cards were twice as profitable as conventional business loans. Drawing on newfound ways to access capital markets, lenders borrowed funds from the markets, supplemented by their own money, to fund consumer debt rather than business investment and remake the possibilities of the American economy. Using new mathematical, marketing, and financial techniques, issuers tipped the scales of capital allocation in the U.S. economy toward consumption over production. For banks to lend, consumers had to borrow. And borrow they did—in record amounts on their credit cards and against their homes. In 1970, only one-sixth of American households had bank-issued revolving credit cards, compared with two-thirds of households in 1998.2 Increasingly the now plentiful credit cards allowed consumers to borrow more money and with greater flexibility than they had before. For home owners, home equity loans also offered a new way to borrow by tapping into the value of their homes. Like credit cards, home equity loans allowed borrowers to pay back their debt when they wanted, without a fixed schedule.

Credit cards and home equity loans—though both revolving debts—still appeared quite distinct from one another in how consumers used them and thought about them. Credit cards bought pants, dinners, and ski vacations. Mortgages bought houses. Credit card debt was unsecured by any claim on real property, while the installment debt of mortgages was secured by a claim on unmovable property. While these two different financial practices—borrowing against a home’s value and borrowing on a credit card—appeared very different for consumers, the business logic and financial practices that underpinned them both grew more and more similar over time. By the late 1980s, these two different debts converged and become financially indistinguishable in how they were funded—by asset-backed securities. By the mid-1990s, even consumers began to use home mortgages and credit cards interchangeably, consolidating the debt of credit cards into the debt of mortgages. How the mortgage and credit became indistinguishable defined a key aspect of the financial transformation of this post-1970s world, reshaping the relationships of lenders and borrowers.

As lenders sought to expand their loans, consumers had new reasons to borrow. While protestors demanded fair credit access for all Americans, innovations in basic financing and lending techniques enabled lenders to profitably extend that access. Home equity loans enabled home owners to borrow against rapidly inflating values of their houses. Credit cards, using new statistical credit scores, allowed more Americans access to plastic than ever before. Mortgage-backed securities, created in the Housing Act of 1968 to fund development in the inner city, paved the way for the easy resale of debt as a financial investment, even as the original development intentions were forgotten. All forms of personal debt became sold as securities, allowing the world to invest profitably in American debt. As wages fell, Americans continued to borrow evergreater amounts, making up the gap between incomes and expectations. Through home equity loans, consumers could easily turn their rising home prices—growing even faster than the inflation that eroded their wages—into money to pay off their credit card bills. Historians who have seen the increase in debt outstanding in the 1970s as a result of increased borrowing, rather than a decrease in ability to repay, have interpreted this rise as a strategic response to inflation. Borrow today and pay back tomorrow when the money is cheaper. Yet few borrowers self-consciously responded to the rise in interest rates. While inflation did not have this strategic consequence for borrowers, it did have an important strategic consequence for lenders, who, in their fixed-rate portfolios, felt the rising interest rate most keenly as they watched their profits fall. Lenders’ business responses to inflation, more than consumers, pushed household debt in new directions that previously, in the most literal sense, had been impossible.

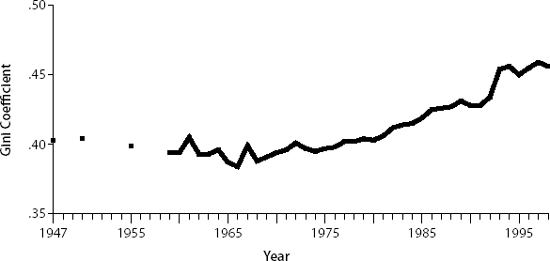

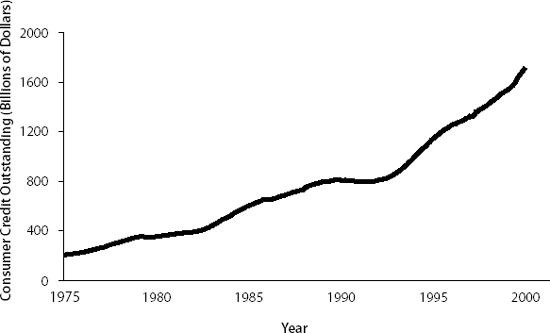

Personal debt after the 1970s was made possible through the global connections of capital that arose after the fall of Bretton Woods. The story of high-flying finance divorced from the everyday lives of Americans, a viewpoint through which financial history is too commonly told, makes as little sense as telling the story of the 1970s only from the viewpoint of consumers. Borrowing and buying, after 1970, took place in a very different world than that of the postwar period, a world where employment and prices were more volatile, where median real wages had fallen for thirty years, and where wealth inequality, which had contracted in the postwar period, had once again began to widen. The aberration of postwar prosperity had ended and the true face of American capitalism—unequal and volatile—had returned with the vengeance of the repressed. The proliferation of revolving credit and home equity loans, as well as securitization, reflected, and to some degree enabled, this changing economic order. While the expansion of debt occurred because consumers were less and less able, on average, to pay back what they borrowed, the massive investment necessary to roll over that outstanding debt required lenders to use capital markets in innovative ways. Moving beyond the resale networks of the mid-twentieth century, new ways to sell debt anonymously on national and even international capital markets inaugurated a new relationship between consumer credit and investor capital. In an insecure world, unsecured debt came of age.

Figure 7.1. Median Male Wages. Source: Robert A. Margo, “Median earnings of full-time workers, by sex and race: 1960–1997,” Table Ba4512 in Historical Statistics of the United States, Earliest Times to the Present: Millennial Edition, eds. Susan B. Carter, Scott Sigmund Gartner, Michael R. Haines, Alan L. Olmstead, Richard Sutch, and Gavin Wright (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006). In 1994 dollars.

Figure 7.2. Income Inequality. Source: Peter H. Lindert, “Distribution of money income among households: 1947–1998,” Table Be1-18 in Historical Statistics of the United States, Earliest Times to the Present: Millennial Edition, eds. Susan B. Carter, Scott Sigmund Gartner, Michael R. Haines, Alan L. Olmstead, Richard Sutch, and Gavin Wright (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Figure 7.3. Consumer Credit Outstanding. Consumers of the 1970s continued to borrow as they had since World War II, but as inequality widened they were increasingly unable to repay what they borrowed. Repayments, not borrowing, were what changed in the 1970s. To fund this borrowing, financiers developed new ways to invest in debt. Source: Federal Reserve, “G. 19, Consumer Credit, Historical Data,” http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g19/hist/cc_hist_sa.txt, accessed December 2009; in billions of seasonally adjusted dollars.

Mortgage-backed Securities and the Great Society

The financial innovation that ultimately allowed capital markets to directly fund any form of debt began with the federal government, not business. In the late 1960s, the federal government sought a way to channel capital into America’s rioting cities. Capital would make possible the Great Society ambitions of saving America’s cities and the newly rising pension funds needed to invest. Ironically, pension funds borne of strong union movements helped provide the justification for policies based on remedying poverty through better access to capital, rather than better access to wages. For Great Society policymakers and promoters, the problems of inequality were framed as a problem of credit access rather than job access. More credit, and not higher wages, would be enough to solve the problems of America’s cities. Toward that end, federal policy fashioned the financial innovation that made possible America’s debt explosion—the asset-backed security—that expanded well beyond its original purpose.

Solving the urban crisis would require solving the housing crisis. But to fix the housing crisis, radical financial innovation would have to occur to maintain the capital flows into mortgages. As the urban riots became the urban crisis, however, mortgage markets had a crisis of their own. American mortgage markets had abruptly frozen—the so-called Credit Crunch of 1966—as investors rapidly withdrew their deposits from banks and put their money in the securities markets. Stocks and bonds offered greater returns than the Federal Reserve-regulated rates available at banks3 Without these deposits, banks could not lend mortgage money. FHA Commissioner Philip Brownstein believed that “our innovations and aggressive thrusts against blight and deterioration, our massive efforts on behalf of the needy, will be lost without an adequate continuing supply of mortgage funds.”4

In a novel move, policymakers seeking a way to fund an expansion of stabilizing home ownership in the cities turned to those same securities markets for new sources of mortgage funds.5 Using markets as sources of capital defined the Great Society approach. Rather than distributing existing mortgages through resale networks as New Deal–era institutions did, markets would guarantee that credit crunches would not interrupt urban development. With the mortgage-backed security, Great Society policymakers tried to harness changes in capitalism to fit its programs rather than trying to regulate capitalism to fit its agenda.

Beyond the immediate crisis of the Credit Crunch of 1966, the old system of buying and selling individual government-insured mortgages through personal connections had already begun to break down over the 1960s. The instruments and institutions through which Americans saved had changed. Beginning in the late 1950s, the big growth in American savings was through pension funds. Pension funds, unlike insurance companies, had little interest in buying mortgages. Whereas insurance companies had large mortgage department staffs whose job was to buy, sell, and collect on mortgages, pension fund managers preferred to invest in stocks and bonds, which could be easily tracked and managed. In 1966, pension funds held $64 billion in assets, according to the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, 60 percent of which were invested in stocks and 25 percent in corporate bonds.6 While pension funds did not have the mortgage departments of insurance companies, they shared the insurance companies’ interest in safe, long-term investments like bonds. To create a new flow of funds, a new financial instrument would have to be fashioned to meet the needs of large institutional investors without the desire or capacity to oversee the collection of a mortgage. If mortgages could be fashioned into an easy-to-invest-in form such as bonds, then pension funds, policymakers believed, would flock to mortgages, which promised a slightly higher return. Making mortgages bond-like, bankers and policymakers realized, would radically expand their investor base, which would have been the goal of such an instrument.

President Johnson announced that to fulfill the aims of his urban housing agenda, he would “propose legislation to strengthen the mortgage market and the financial institutions that supply mortgage credit.”7 Government studies in the aftermath of the “deplorable” credit crunch insisted, in the words of Senator John Sparkman, chairman of the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency, that action be taken to “insure an adequate flow of mortgage credit for the future.”8 The solution, Sparkman asserted, lay in “correcting deficiencies in our financial structure.”9 FHA officials, like Philip Brownstein, believed the mortgage-backed security “may very well be the break-through we all have been seeking for many years to tap the additional sources of funds which so far have shown little interest in mortgages.”10 Disparate groups, from bankers to unions, demanded Congress fashion a “new security-type mortgage instrument” to channel the money invested in the securities markets into mortgages.11 With the support of the mortgage industry, as well as politicians, this mortgage instrument encountered few obstacles. Even the Fed, whose authority would be hampered by such an invention, encouraged Congress to consider creating debt “instruments [issued] against pools of residential mortgages” to “broaden [the] sources of funds available for residential mortgage investment,” so as to “rely less on depository institutions that tend to be vulnerable to conditions accompanying general credit restraint.”12 Creating such instruments would undermine the Fed’s ability to affect mortgages through its monetary policy, and in turn weaken its control over the money supply, but quarantining mortgages from the rest of the economy would also put the Fed, if need be, beyond public blame.

The Housing Act of 1968, which implemented this vision, remade the American mortgage system in a way that had not been done since the New Deal. Congress privatized the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA) and created its signature financial instrument—the mortgage-backed security.13 At the same time, the Housing Act inaugurated a shortterm program, called Section 235, which used these mortgage funds to loan money to low-income borrowers, whose interest would be directly subsidized by the government.14 Through mortgage-backed securities and these low-income loans, policymakers hoped to stabilize the unrests of the American cities.15

These Section 235 loans allowed low-income buyers with little or no savings to buy new and pre-existing homes. The program provided billions of dollars in financing for millions of homes during its operation. The federal government’s role in housing in 1971, when federal programs subsidized 30 percent of housing starts, was shockingly higher than in 1961, when only 4.4 percent did, with “much of the increase in housing units . . . occur[ing] in section 235,” according to Nixon administration officials.16 Government-sponsored mortgage debt accounted for 20 percent of the overall increase in mortgage debt in 1971.17 While in operation, the Section 235 marshaled new financial instruments to transform hundreds of thousands of Americans from renters to owners. Section 235 created such an upswing in housing that by 1972 the president of the Mortgage Bankers’ Association could pronounce it the “principal system” for low-income housing.18 One prominent mortgage banker declared that Section 235 “answered the cry, ‘Burn, baby, burn’ with ‘Build, baby, build!”19 Eighty percent of the funds were earmarked for families at or near the welfare limit. A home buyer who qualified for the program would receive an interest-subsidy every month such that the government would pay all the interest above 1 percent. Sliding scale down payments, which reached as low as $200—two weeks’ income for the median Section 235 buyer—would enable even the very poor to own a house.20 If the borrower defaulted, the government would pay off the balance of the loan. Home buyers could borrow up to $24,000 as long as FHA house inspectors declared the property to be in sound condition. Having bought a home, their monthly rent payments would become equity instead. Section 235 would build wealth. FHA administrators like Brownstein believed the Section 235 program “[broke] down the remaining barriers to the fullest private participation in providing housing for those who are economically unable to obtain a decent home in the open market.”21 By definition, Section 235 lent to borrowers who could not get a mortgage from conventional lenders. The program intentionally sought out the riskiest borrowers that Brownstein described as “families who would not now qualify for FHA mortgage insurance because of their credit histories, or irregular income patterns.” Section 235 buyers had no normal access to home financing. The program offered them their only chance for home ownership. The Section 235 program lasted only a few years, eventually bought down by scandals eerily reminiscent of today’s subprime crisis, as realtors, builders, home inspectors, and mortgage bankers colluded in unsavory ways to defraud trusting first-time buyers without alternatives for home ownership.22 Nonetheless, the mortgage-backed security invented to fund the program persisted, and in the long-run, exceeded the reach of its original purpose, enabling new sources of mortgage capital for home buyers of all incomes.

While in theory the mortgage-backed security allow borrowers to bypass financial institutions and borrow directly from capital markets, in practice, a long chain of financial institutions still mediated the connection between borrower and lender, and it was the way in which the mortgage-backed security fit those institutional needs that made it such a success. Making the mortgage-backed security work required adjusting the financial institutions that constituted the mortgage market—mortgage companies, institutional investors, and the FNMA. The FNMA existed before the credit crunch, but the Congressional response to the credit crunch remade FNMA into a new kind of institution, even more privatized and market-oriented—with a new kind of financial instrument containing great possibilities. Created in the New Deal to buy and sell government-insured mortgages across the country, FNMA had forged a national secondary market for mortgages offered through the FHA. During the 1960s, however, the federal government had created more and more socially oriented, specialized housing programs that relaxed the FHA’s lending requirements, especially in the inner city. FNMA had resold these mortgages alongside the other mortgages. Many policymakers believed that the “credit requirements” used by federal lending programs were “too stringent,” overlooking potential borrowers’ “true merits.”23 Only “liberalized” mortgage financing, which relaxed the FHA’s strict standards, would provide financing to low-income buyers or in low-income neighborhoods.24 Though mortgage officials at the FHA were critical of this policy, loose lending policies found support across the aisle in Congress.

Though privatized, the Housing Act still provided extensive federal oversight over FNMA, explicitly ruling that the secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), even after FNMA’s privatization, could still require FNMA to purchase low-income mortgages.25 Internal matters to FNMA would be private, but larger market actions would remain partially under government control. The Act spun off a new agency, the Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA or Ginnie Mae), which would handle all the subsidized mortgage programs. Splitting FNMA into two organizations—FNMA and GNMA—would cordon off the welfare programs from the market programs, and privatization would take the welfare expenses, to a large degree, off the federal budget because mortgages bought and sold would not look like a government expense on the accounting sheets, enabling the expansion of federal mortgage lending. Only the subsidies to GNMA, and not the total mortgages bought, would go on the books as a federal expense.26

Mortgage-backed securities initially came in two forms: the “modified pass-through” security and the “bond-like” security. Both forms gave the investor a claim on the monthly principal and interest payments of a large, diversified portfolio of mortgages. Both forms rendered the investor’s connection to the underlying assets completely anonymous and secondhand. The differences between them initially irked the mortgage banking industry, however. The pass-through security delivered the real monthly principal and interest payments of the portfolio, minus a servicing fee, to the investor. The bond-like security provided a steady, even payment of principal and interest to the investor. The monthly variance for the pass-through security made it different than a normal bond, which mortgage bankers thought would reduce demand. The pass-through security could vary because of mortgage prepayments, defaults, and any of the other risks incurred with a mortgage. The bond-like security hid those events. While the pass-through mortgage-backed security provided new opportunities for tapping new institutional investors, mortgage bankers remained disappointed.27 What they had wanted was a true bond, guaranteed by GNMA, with fixed guaranteed payments, not a bond-like passthrough instrument, in which they doubted investors would be as interested. Mortgage bankers had envisioned trading their mortgages for a bond, which would be sold at auction. Such a bond, with its underlying assets completely hidden to the buyer, would make mortgage reselling truly competitive, that is to say interchangeable, with other forms of bond issues.

In August 1969, the newly founded GNMA announced that it would be offering mortgage-backed securities for the first time.28 After receiving suggestions from financiers, policymakers, and potential investors for the regulations surrounding the securities, GNMA, in association with FNMA, issued the first mortgage-backed securities on February 19, 1970. Three New Jersey public-sector union pension funds bought $2 million worth of pass-through securities from Associated Mortgage Companies, a sprawling interstate network of mortgage companies.29 Soon thereafter, in May 1970, GNMA had its first sale of bond-like mortgage-backed securities, selling $400 million to investors.

While at first the bond-like mortgage-backed securities outweighed the pass-through mortgage-backed securities, the tables quickly turned. Within the year, in 1971, GNMA and FNMA sold over $2.2 billion in pass-through mortgage-backed securities and $915 million in bonds. Within a few years, in fact, GNMA stopped offering the bond-like mortgage-backed securities entirely. For the bond-like mortgage-backed securities to work, the pools had to be enormous, at least $200 million, and the mortgage company had to have enough capital to guarantee the payments in case of default. Few private companies sold so many mortgages and none had the requisite capital. The pass-through mortgage pools could be much smaller—only $2 million. Private mortgage companies had to content themselves with pass-through mortgage-backed securities, and the mortgage companies could more easily acquire and bundle mortgages than GNMA or FNMA.

The drawbacks that mortgage bankers initially feared turned out to matter little. In many ways how the mortgage-backed security fit the institutional needs of investors mattered as much as the rate of return. While not a true bond, the pass-through security completely hid the hassle of mortgage ownership—the paperwork and collection—while still providing higher returns than government securities, and unlike corporate bonds, the mortgage bonds had foreclosable assets backing the debt. The market mediation that made the mortgage-backed security easier for mortgage companies—No personal networks! No salesmanship! Just buy a typewriter and some GNMA application forms!—made even the pass-through security much more appealing to investors than directly owning the underlying mortgages. Investment required no specialized knowledge of mortgages or even housing—the mortgage-backed securities could be compared to other bonds, whose safety was rated by Standard & Poor’s. The mortgage-backed security eliminated the need to know about the underlying properties or borrowers. As Woodward Kingman, president of the GNMA noted, “this instrument eliminates all the documentation, paperwork problems, and safekeeping problems that are involved in making a comparable investment in just ordinary mortgages.”30 Institutions, big and small, did not need a mortgage department to track payments, check titles, or any of the myriad other details involved in mortgage lending. The institution just needed to file the security. Instead of tracking fifty individual $20,000 mortgages, an investor could just buy the mortgage-backed security for $1,000,000. The mortgage-backed security lowered the accounting costs by making the investments enough like a bond to attract the notice of institutional investors.31 Investors embraced the new securities, although not always the investors that the creators of the mortgage-backed securities had originally intended.

At first, surprisingly, the biggest buyers of mortgage-backed securities were not pension funds but local savings and loan banks. Mortgage-backed securities turned out to be a great way for local banks, legally limited in their geographic scope, to invest in distant places.32 Many states forbade local banks from lending money beyond a certain distance, but had no such provision against the buying and selling of bonds. Mortgage-backed securities allowed capital mobility for all financial institutions, but in allowing savings and loan banks such access, they did not increase the net available funds for mortgages as a nation, since savings and loan banks already invested in mortgages. Such purchases could, however, move funds to capital-poor areas.

With the declining investment in FHA loans in the 1960s, local home buyers outside of the capital-rich east found it harder to find funds for a mortgage since there was no comparable national market for conventional mortgages as there was for federally insured mortgages.33 Every house was unique, which made reselling mortgages difficult. FHA loans had established a secondary market and national lending for distant mortgagees because, through its guarantee and its standards, the FHA created a homogeneity that allowed those loans to be sold as interchangeable commodities.34 All loans that were not federally insured, so-called “conventional mortgages,” had no such secondary market. No conventional mortgage, by itself, could be so homogeneous as to be traded across the country. Mortgage lending, for the conventional market, required local knowledge that no distant mortgage banker could have.

While FNMA could resell federally insured mortgages, such loans grew less important each year in the 1960s. Though the mortgage banking industry had flourished through its ability to originate FHA and VA loans, and then resell them on the secondary markets through FNMA, this reselling could not be done for conventional loans. While federally insured mortgages made up a large portion of American borrowing, it was a good business model, and helped move substantial amounts of capital across the country. After World War II, the use of conventional mortgages had fallen as Americans turned to FHA and VA mortgages to finance the suburban expansion. Around the late 1950s, however, the use of conventional mortgages stabilized at about half of all mortgages issued, and then began to grow again. By the mid-1960s, conventional mortgages accounted for two-thirds of all mortgages. In 1970, conventional mortgages—though double the volume of federally insured mortgages—had no national secondary market. For mortgage companies, this rise in conventional mortgages was dire. While mortgage companies originated 55 percent of federally insured loans, mortgage companies originated only 5 percent of conventional loans.35 And with fewer investors buying federally insured mortgages, demand fell along with supply. The possibilities of a mortgage-backed security for conventional mortgages excited mortgage bankers, because as American consumers moved away from federally insured mortgages their core business shrank.

To create a secondary market for conventional mortgages, Congress, in the Emergency Home Finance Act of 1970, authorized the creation of the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC or Freddie Mac), which drew on the mortgage-backed security financing techniques developed in the Housing Act of 1968. Like FNMA, FHLMC could buy and sell mortgages and issue mortgage-backed securities. Unlike FNMA, Congress intended FHLMC to buy its mortgages primarily from savings and loan banks rather than mortgage companies. Otherwise, the two corporations were largely identical. By this point, mortgage experts, like FNMA executive vice president Philip Brinkerhoff, recognized that finding new sources of capital could “be accomplished more efficiently through the issuance and sale of mortgage-backed securities than through direct sale of mortgages.”36

FHLMC learned from FNMA and, in November 1970, almost immediately after its inception, issued mortgage-backed securities. While this first group of loans was federally insured and not conventional, FHLMC demonstrated to skittish investors that it could buy mortgages and issue mortgage-backed securities. Having its first portfolio insurable guaranteed that existing mortgage-backed security investors would buy the first issue. Thereafter, FHLMC began to transition into conventional mortgages, developing innovative methods to standardize conventional mortgages. Even if the home differed, standardization of information helped their commonalities come to the fore. FHLMC developed a national computer network called AMMINET to provide up-to-the-minute information on mortgage-backed security trades and issues, creating a real national “market” with national information.37

By 1972, FHLMC, with established procedures for credit evaluation, loan documents, appraisals, mortgage insurance, and mortgage originators, began to issue completely conventionally backed, mortgage-backed securities—creating the first national conventional mortgage market. More than just standardization, however, conventional mortgages could be traded because they were issued through mortgage-backed securities and not the old assignment system of the 1950s. While the FHA mortgage reduced investors’ risk by homogenizing standards, the FHLMC reduced risk by heterogeneous diversification. The mortgage-backed security came with a pre-diversified portfolio for a given interest rate, so that the investor did not need to cherry-pick mortgages across regions and neighborhoods. The risk of one bad loan could be diluted across many good loans in a mortgage-backed security’s underlying portfolio. Mortgage portfolios backing the securities brought enough diversification, it was believed, to overwhelm any outlying bad loan. For investors who would never see the property, such risk-reduction was essential. FHLMC substituted risk-reducing portfolio diversification for risk-eliminating federal guarantees.

For GNMA and FNMA, the federal government lent its authority to their operations, and FHLMC, in mimicking them, acquired their patina of government insurance. Beyond the portfolio diversification, as a last resort, the Housing Act of 1968 had also authorized the Treasury Department as a “backstop,” or buyer of last resort to the market, enabling them to buy up to $2.25 billion of FNMA mortgage-backed securities if they could not be sold.38 Otherwise, FNMA was considered to be private—paying taxes and earning profits.39 But this amount the Treasury could “backstop” was more important symbolically than practically, as it amounted to only about half of FNMA’s annual mortgage purchases in 1972. Investors wanted the reassurance that the unlimited tax-collecting resources of the federal government stood behind the securities, even if, legally, there was not an unlimited backstop. While GNMA and FNMA announced in their publications that the “full faith” of the U.S. government stood behind their issues, the reality fell far short of the promise—but for investors, it was close enough. Dangling promises, diversified portfolios, and foreclosable houses convinced many investors.

The mortgage-backed security had come into its own and quickly began to define how mortgage funds flowed in the United States. By 1973, FHLMC was buying three times as many conventional mortgages as federally insured mortgages—nearly $1 billion in conventional mortgages.40 The next year, 1974, FHLMC further doubled its conventional mortgage activity to nearly $2 billion and shrunk its purchases of federally insured mortgages to $261 million.41 This rapid expansion into an uninsured market was made possible through FHLMC’s assiduous mimicry of the debt instruments of GNMA and FNMA, which continued through 1972 to deal primarily in federally insured mortgages. By the end of 1973, FNMA was, next to the Treasury, the largest debt-issuing institution in U.S. capital markets.42

Mortgage-backed securities rescued the mortgage banking industry and preserved the easy access to mortgage funds that middle-class Americans had come to expect. Capital markets became a central source of funds, as the older institutional investor and small depositor arrangements had collapsed in the face of rising interest rates and shifting savings practices. By 1970, withdrawals at savings and loan institutions exceeded deposits nearly every month.43 The president of the Mortgage Bankers of America, Robert Pease, declared at their annual convention that, “except for FNMA, there is almost no money available for residential housing. We are in a real honest-to-goodness housing crisis!”44 On average in 1971, $50 million worth of mortgages flowed from the capital markets through mortgage-backed securities into American housing each month.

In both the cities and suburbs, mortgage-backed securities provided new sources of mortgage funds. While direct mortgage assignment collapsed, mortgage-backed securities provided the financing to dramatically increase the new housing programs in America’s cities. Federally subsidized mortgages, resold as FNMA mortgage-backed securities, propelled the American building industry in 1970, accounting for 30 percent of housing starts (433,000) and 20 percent of the mortgage debt increase.45 In the first year of sales, GNMA issued over $2.3 billion in mortgage-backed securities, funneling money backwards into federal housing programs.46 Typifying the connection in many ways, the first company to bundle enough mortgages for resale, as discussed earlier, was Associated Mortgage Companies, Inc., whose advertisement for its pool of mortgages, “Ghetto ready,/ghetto set,/go!,” illustrated the explicit connection between funds for inner-city America and mortgage-backed securities.47 Mortgage company lending surged as well, providing 90 percent of FNMA’s purchases.48 By January 1973, mortgage companies originated more conventional mortgages than FHA or VA loans.49 Moving away from a reliance on bank deposits, the mortgage industry had been rebuilt atop a new foundation of securities.

The mortgage-backed securities also promoted the lending of mortgage dollars even further down the economic ladder, to those borrowers outside the federally subsidized programs. By November of 1972, FNMA had begun to emulate FHLMC and began to buy mortgages that covered up to 95 percent of a house’s price.50 FHLMC had offered them earlier, but for two firms created and privatized to compete with one another and to service different kinds of financial institutions, competition drove them both to similar lending programs. Mortgages with as little as a 5 percent down payment could now be repackaged and sold as a security. FNMA actuaries calculated that the rate of default on a 95 percent mortgage was three times higher than on a 90 percent mortgage. The higher risk required a higher yield, but investors trusted the U.S. government to make good on the payments, even when the American borrowers could not. Yet, the assurance of payment was not sufficient to draw pension funds to invest in the mortgage-backed securities in the amounts that the creators of the securities had imagined they would.

Mortgage-backed securities, by the mid-1970s, sold in great numbers, but not exactly as the framers of the instrument had intended. While pensions bought over half of the bond-like mortgage-backed securities (52.72 percent) within a few years, such bonds were not sold any longer and pension funds resisted buying the far greater volume of pass-through mortgage-backed securities, bought by the savings and loan banks.51 As Senator Proxmire remarked in Congressional hearings on the secondary mortgage markets, the increase in mortgage-backed security buying by pensions, while “commendable,” was still a low relative share of the market.52 Pension funds, intended to be the primary source of investment for mortgage-backed securities, accounted for only 21 percent of FNMA mortgage-backed security ownership.53 Though GNMA actively sought investment from pension funds, as late as 1975 such funds accounted for only 8.29 percent of 1975’s purchases of pass-through mortgage-backed securities. Savings and loan institutions bought 41 percent of the passthrough mortgage-backed securities. Pension funds’ share of purchases rose, but did not take on the leading role policymakers had hoped for in providing a new source of mortgage capital. FNMA and FHLMC did, however, provide leadership to the U.S. mortgage market. With the creation of mortgage-backed securities, FNMA’s centrality to American mortgage markets increased, sometimes supplying by the mid-1970s as much as half of all new mortgage funds in a given quarter.54

Mortgage-backed securities offered institutional investors stable, bondlike investments in mortgages and provided American borrowers a growing source of mortgage capital. Low-income mortgage lending, funded through those mortgage-backed securities, contained the possibility of giving inner-city renters a stake in their cities to quell, as legislators hoped, the urban unrest. While low-income mortgage lending, in the Section 235 program, quickly fizzled in scandal, not to return in great numbers again until the end of the century, mortgage-backed securities equally quickly assumed a central role in the economy. Savings and loan banks bought these early mortgage-backed securities, substituting their easy administration, low risk, and higher yields for their own mortgages, which did not add, on net, to the level of available mortgage capital. Pension funds—the investors for whom the mortgage-backed security was constructed—still remained minority buyers, but through changes over the next few years would find other ways to invest in American mortgages.

Home Equity Loans and Adjustable-rate Mortgages

While critics gaped at the rising levels of outstanding debt in the late 1970s, economists and social critics always seemed to exclude mortgages from these calamitous computations. These numbers were supposed to reflect the dangerous debt, not the responsible debt. Mortgages, after all, were good debt, helping Americans “own” their homes. Home owners “built equity” by repaying their principal—along with the interest on the debt—every month. And if the value of the home rose, which they had in every year since the Great Depression, then home owners would reap 100 percent of that increase. Houses were the easiest way for people to leverage their equity—multiplying the reward on an increasing value of an asset. Though home owners paid interest on the mortgage, they could get the entire increase in house price. While borrowing on the margin to buy stocks was seen as risky, buying a house with a mortgage was seen as prudent. Homes, for most Americans, were the only kind of financial leverage to which they could have access. For many, such leverage paid off handsomely in the late 1970s. While the average price of houses doubled between 1970 and 1978, the overall consumer price index rose only 65 percent.55 Equity owned nearly doubled from $475 billion in 1970 to $934 billion in 1977.56 Housing prices rose faster than other consumer goods. The inflation-driven rise in house prices provided a broad spectrum of home owners a lot of equity. This paper wealth of equity, however, mattered little since home owners of the 1970s could not use it without selling their home.

Bankers first offered home equity loans in the 1970s to fill just this need. Home equity loans made the value of a home owner’s house more accessible. The equity could be spent while still living in the home. Second mortgages had existed since the nineteenth century—though they became less common with the expansion of FHA loans, which forbade such “junior mortgages”—but home equity loans were more like credit cards than a junior mortgage.57 Home owners could arrange a line of credit and then borrow up to that limit as they liked, repaying the debt irregularly. With flexible access to the credit line, home equity allowed consumers to move money in and out of their house as they saw fit. Easy access to home equity meant that home owners could use the equity of their house to consolidate their other debts, and unlike credit cards, if the borrower did not repay the debt, the lender could foreclose on the house.

The artificial distinction between non-mortgage and mortgage debt, underpinned by this idea of inevitably rising house prices, obscured the ever-growing equivalence between these forms of debt, and legitimated home owners’ borrowing against the value of their houses. Borrowing against a house, on some level, required less financial reasoning than comparing two credit card offers. Comparing interest rates required mathematical skills to calculate the costs and benefits of switching, and the answer was strictly numeric. Borrowing against a house was rooted as much in ideas of ownership as in cold calculations. Home owners already “owned” the equity. It was theirs to spend. The feeling of ownership allowed the choice to be easier than the choice between credit cards, and non-numeric. Yet, the danger of foreclosure remained. Even in 1983, a banking journal wrote that, “the public hasn’t taken too kindly to resales, refinancings, and second mortgages.”58 Caught between “the conflicting desires of minimizing taxes and owning their homes outright,” many debtors resented the home equity loan, even as they took greater advantage of it.

These home equity loans were unlike traditional fixed rate mortgages in other ways too. At the center of lenders’ innovations in the late 1970s was the floating interest rate. In an era of stable, low-interest rates, like the postwar period, lenders could comfortably extend credit at a fixed rate of interest. The sharply rising interest rates of the 1970s, however, made many banking practices unprofitable. Lending long-term mortgages at a low rate and forced to borrow from depositors at high rates, bankers sought out a new way to lend money. A floating interest rate solved their problem. Mortgages with adjustable rates allowed banks to lend money without incurring interest rate risk. Such adjustable rates shifted the risk of a rising interest rate to the borrowers, who, also with fixed incomes, would be even more unable to weather such a shift in their payments than institutions.

In the early 1980s, adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) and secondary markets made commercial banks’ re-entry into mortgages profitable again—and easier.59 If banks wanted mortgages in their portfolios, ARMs allowed them to do so without interest rate risk. If they wanted a quick resell, secondary markets, including mortgage-backed securities, were deep and easy to use, which was necessary if banks were to lend money for mortgages. While bankers embraced the variable rate mortgages, relatively few borrowers did. Attempting to switch borrowers from fixed to variable rate mortgages, banks offered introductory teaser rates, as much as 5 percent lower than the market fixed rate mortgage.60 Despite teaser rates, ARMs comprised only 11 percent of all mortgages in 1984.61

Fixed rate mortgages continued to be the most popular mortgages for borrowers, but presented unacceptable risks for lenders. While it was possible for bankers to offer fixed rate mortgages and hedge the risk of interest rate changes through derivatives, such hedging was outside the skills of most bankers. Even the slightest miscalculation or misunderstanding of how the derivatives functioned could expose a bank to serious losses. Few commercial bankers could carry out a complex hedge strategy against interest rate fluctuations. While mortgage companies with limited capital had securitized mortgages since the early 1970s, banks increasingly used mortgage-backed securities to reduce their interest rate risk. By securitizing the mortgages, banks could collect a steady, interest-rate-independent stream of servicing income and leave the risk of interest rate fluctuations to someone else.62 Once banks began to resell loans, the advantages were overwhelming. Only a third of commercial banks, in 1984, resold mortgages to the secondary markets.63 But those that did sell, sold nearly all—90 to 100 percent—of their mortgages.64

If banks sold off fixed rate mortgages whenever possible, they held onto home equity loans. While lenders struggled to move borrowers into variable rate mortgages, only 4 percent of creditors offered fixed rate home equity loans.65 Forty percent of creditors even offered interest-only loans, unheard of at the time in standard mortgages, because the principal was never repaid.66 As one banker in Fort Lauderdale remarked, “the yield is so good on these [home equity] loans that my parent company doesn’t want to sell any.”67 More than half of all bank advertising dollars were directed at home equity loans by 1986.68 Eighty percent of home owners knew about home equity loans and 4 percent of home owners had them.69 Large consumer finance companies as well, like Household, began in 1980, “redirecting assets from less profitable areas into more profitable activities[,] in particular, real estate secured loans.”70 In the next two years, home equity loans, with variable rates, rose from 34 percent of Household’s portfolio to 50 percent. Household’s reallocation of capital is understandable since it realized a return on its loans of 5.6 percent.71 By the early 1980s, faced with a rising cost of funds, variable rate home equity loans appeared ideal, even for the larger banks. In a joint interview with leading bankers, the consensus on the great challenge to consumer banking was the same: the cost of funds. George Kilguss, senior vice-president of Citizens Bank, remarked that “unless you have variable-rate installment loans, you run into a problem.”72 Kilguss expected Citizens would begin to offer an “open-end credit line with a variable rate in 1983. Equity mortgages will secure these lines, which we expect to be large.” Home equity loans offered banks a way to offer consumers variable rate credit, which solved their cost of funds problem, and offered banks more secure collateral. While banks explored the possibilities of secured lending, they also expanded the boundaries of unsecured lending through innovations in credit card lending.

Collateralized Mortgage Obligations, Tranches, and Freddie Mac

Extending the pass-through mortgage-backed security into other forms during the 1980s, financiers opened up the financing of consumer mortgages. While pass-through mortgage-backed securities offered investors a more bond-like investment, they were still not bonds. And the mortgage-backed securities still had other drawbacks: time and risk. Not all investors wanted a long-term investment over the life of the mortgages, yet they wanted the security and return of investing in house-backed securities. In June 1983, FHLMC, in association with the investment banks Salomon Brothers and First Bank of Boston, issued the first collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO).73 The CMO worked just like a mortgage-backed security of the 1970s except that instead of a single kind of bond, each mortgage pool was split up into several different kinds of bonds. These kinds of bonds were called “tranches,” from the French word tranche, meaning “slice.” Rather than a mortgage-backed security having a single maturity and interest rate, the CMO sliced the mortgage-backed security into multiple bonds, each with a different maturity date and interest rate. The first CMOs offered by FHLMC had three tranches, arbitrarily named A-1, A-2, and A-3, each of which had a different maturity and interest rate.74 The first tranche had a five-year maturity, the second a twelve-and-a-half year maturity, and the third a thirty-year maturity. All tranches received interest payments, but principal payments only went to the tranche with the shortest maturity.75 The shortest maturities have the lowest risk of default or prepayment, since they received the principal payments, and they also received the lowest interest rates.

Tranches made investing in mortgages, especially the short-term tranches, a more certain investment. Early prepayment risk, when interest rates fell and borrowers refinanced, upset the calculations of investors, as did the uncertainty of defaults. The longest maturities, with the highest risk of default or prepayment, commanded the highest interest rates. In CMOs, investors could find what they needed to match their investment needs. The CMO allowed the staid mortgage to split into a variety of securities, each with a unique rate of return different from that of the original mortgage. A mortgage could be a high-risk, high-return investment. A mortgage could be a quick-paying, low-risk investment. With the right math, a mortgage could be turned into anything.

Slicing the mortgage-backed security into tranches expanded the potential investor pool. Institutional investors wanted investments that came due when their obligations came due, like an insurance company paying death benefits or a pension fund beginning to fund a retirement.76 Mortgages and mortgage-backed securities had only long-term maturities. With different maturity dates, the tranches allowed investors to match the dates of their obligations with the maturity of their investments. Insurance companies, for instance, would statistically know what fraction of their life insurance policies would come due, hypothetically, on January 3rd, 1987. The company would want enough of its investments to come due on that day to cover those expenses, but not more and not less. If the investment matured earlier, then the insurance company would have to find another investment, which cost money. If the investment matured later, then the insurance company would not have the cash to meet its obligations. Different investors—insurance companies, pension funds, banks, etc.—all had different time frames and the tranches enabled mortgage investments to fit these time frames, from just a few years to several decades, rather than the real timeframe of mortgage repayment.

Tranches allowed a wide spectrum of investors to put their money in mortgages and tested the limits of the charters of the government-sponsored enterprises that created them. FHLMC President Kenneth Thygerson, upon his retirement in 1985, proudly claimed to have “tried to extend the barriers to the limits of the corporation’s charter. Future opportunities will require an act of Congress, so this is the time for me to look to the private sector.”77 These limits could only be extended by using the most recent technologies. Slicing mortgage-backed securities into tranches required elaborate payment calculations—not only for Freddie Mac, but for investors as well. As Dexter Senft, a First Boston investment banker who worked on the first CMO, remarked, “these products couldn’t exist without high-speed computers. They are the first really technologically-driven deals we’ve seen on Wall Street.”78 Pricing all those tranches, and paying them, required computing power unavailable only a few years earlier. Innovations like the CMO gave Freddie Mac access to new sources of profit as well as new investors. In the three years Thygerson was with Freddie Mac, its portfolio increased four-fold from $25 billion to $100 billion, as its profits increased nearly five times. In the private sector, the rules governing Freddie Mac would not apply, allowing Thygerson, and others like him, to extend the boundaries of finance to places unimagined. The next appointed president of Freddie Mac, Leland Brendsel, who had been directly responsible for the first CMO as Freddie Mac’s CFO, reflected the importance of the CMO to Freddie Mac’s future.79 Other financial institutions began to offer CMOs, substituting the government’s backing for their own, or their credit insurance companies. Citibank, for instance, offered its first CMO in 1985—using its large resources to smooth out the repayment schedule—by providing minimum guaranteed principal and interest payments.80

For the home owners financed through mortgage-backed securities and CMOs, however, the complex debt instruments remained largely opaque, and unimportant. When John and Priscilla Myers of Lancaster, PA, bought their $47,000 two-bedroom split-level in 1984, they went to their local savings and loan for a fixed mortgage.81 Since their local savings and loan, like all banks of the 1980s, feared holding onto fixed rate mortgages, the mortgage was resold and pooled into a CMO. For John Myers, the actual owner of the mortgage did not “make a difference . . . as long as Priscilla and I were able to get the money for the house.” The flood of money from pension funds and other nontraditional investors into mortgage-backed securities gave the Myers the ability to buy their home. While CMOs transformed the mortgage industry, and the amount of capital available to borrow, they also opened the door for turning any other kind of steady stream of income into a security. This alchemical science of turning assets into securities, after it had been perfected with the CMO, underpinned the expansion of many other debt instruments of the 1980s, such as credit cards. Soon the Myers family, and millions of other Americans, would be able to borrow much more than just a mortgage from capital markets.

Credit Cards in the 1970s

Despite their high interest rates, the profitability of credit cards has fluctuated over the past thirty years, sometimes eking out only marginal profits. While Americans always paid a higher interest on credit cards than any other form of debt, the credit card companies—“issuers” in the industry-speak—faced many challenges: the cost of funds, borrower default, finding new creditworthy borrowers, and firm competition. Making credit cards profitable required clever business strategies that challenged conventional ideas of creditworthiness as much as conventional understandings of capital. During the 1970s, those who had access to revolving credit shifted their debts away from installment credit.82 But only the most creditworthy households (35 percent) had bank cards in 1977—double the number in 1970 but still not a majority of American households. Before 1975, retailers continued to serve as the primary source of revolving credit, but such credit was limited in its use to individual stores.83 Only ten of the one hundred largest department stores in the United States took bank credit cards before 1976, continuing to rely on retail credit cards to maintain store loyalty.84

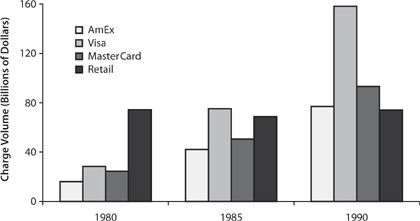

Universal credit cards that could be used anywhere had existed in various guises since the 1950s, but were not widespread until the late 1970s. In the early 1960s, merchant billing networks were proprietary—Diner’s Club and American Express each billed merchants for their own cards. In 1966, banks set up two separate networks that separated the billing of merchants from the lending of consumer credit. Bank of America, in 1966, began to allow other banks to use its billing system—BankAmericard. Also in 1966, another group of banks started the Interbank Card Association, which became MasterCard in 1980, in a bid to share the costs and difficulties of expanding merchant participation. Bank of America spun off BankAmericard in 1970 to the banks that used the system, eventually rebranding itself by 1977 as VISA. These two systems standardized merchant fees, but allowed issuers to charge borrowers whatever they liked, which allowed banks to focus on lending to consumers and not selling their card systems to merchants.85 At first member banks could only use either VISA or MasterCard, but by 1975, after a lawsuit, such restrictions were dropped.86 The proliferation of VISA and MasterCard allowed credit cards to be used by more merchants, which in turn made them more useful for consumers.

In the late 1970s, bank cards were issued only to the most creditworthy borrowers, who tended to repay what they borrowed, and consequently banks’ profits were meager. The primary challenge for credit card issuers was that the borrowers least likely to default also tended to pay off their debt every month—denying the creditors any interest income. These “non-revolvers,” who did not revolve their debt from month to month, treated credit cards like mid-century charge cards. In contrast, borrowers who might not pay off their debt every month had a higher chance of not paying at all, leading to “charge-off” or a complete loss on the loan. Between the non-revolver and the defaulter was the much sought-after “revolver,” who paid the interest every month but not the principal. This sweet spot of revolving debt promised the highest profit rates for credit card companies, but differentiating the revolver from the free-loading non-revolvers and defaulters was extremely difficult. For the credit card companies of the 1980s, revolvers were profitable but lending to them went against the easy risk management models based on guaranteed repayment developed in the era of installment credit.

Issuers also faced the challenge of consumers’ expectations of how they should behave. Unlike department stores, where most consumers used revolving credit until the mid-1970s, credit card issuers sold no goods. The income from the cards was the only income. Consumers had always been told by retailers to pay their charge account bills on time, which generalized a particular connection between profit and repayment into a more general moral principle. What these credit card companies called “revolvers” had historically been called “slow-payers” and had been the bane of all earlier creditors. Slow-payers tied up retailers’ expensive capital. Though borrowers who paid their debts on time still thought of themselves as “good customers,” the logic of revolving credit was different—profitable customers revolved their debt. In 1980, 37 percent of VISA customers, accounting for half of VISA’s credit volume, paid their bills in full and thus incurred no finance charges.87 Consumers believed they were good customers when they paid their bills, but they actually were bad customers, at least from the perspective of the lender.

Proper consumers, but not profitable ones, resisted the idea that they were doing something “wrong.” Non-revolvers abided by the compact created through generations of credit use, now firmly inscribed in common sense. But these proper customers lost money for the d issuers and the easiest way to rectify that was simply to charge them a fee for their unprofitable behavior. Citibank in April 1976, for instance, attempted to charge a 50 cent fee to customers that did not maintain a balance.88 Incensed that good customers were charged fees, the House Consumer Affairs Subcommittee conducted investigations, at which William Spencer, the soon-to-be president of Citibank told the committee, “you obviously do not believe that we are, in fact, losing money on this portion of the business. Let me assure you the contrary.”89 Whether because of threatened legislation or “competitive pressure,” as a Citibank spokesperson claimed, the fee stopped in December 1976. Even the possibility of a fee, it turned out, was struck down two years later in 1978 by the New York Supreme Court, and Citibank was forced to return the fees to its customers.90 The business solution, in the 1970s, to non-revolvers could not simply be a fee, but something that satisfied both the bottom line and the moral expectations of customers. Rather than charge fees afterwards to those who were not revolvers, credit card companies would have to find the revolvers ahead of time. The entire system by which lenders conceived of “creditworthiness” was geared, however, to screening out revolvers. To make revolving credit more profitable for bank lenders, new criteria would have to be developed.

Discrimination and Discriminant Analysis

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act implemented through the Federal Reserve’s Regulation B pushed lenders toward more “objective” models of lending that excluded race, sex, and other protected categories—defined by the Fed as “demonstrably and statistically sound” models. These statistically sound models were required to avoid any inkling of sex or race discrimination. Understandably, lenders quickly developed in-house models, subcontracted them, or bought them from third-party companies, in an effort to avoid legal tussles. The credit scoring system offered by GECC, for instance, promised to be “discriminating enough to accurately determine credit worthiness, yet objective enough to avoid discrimination.”91 While these models were kept secret from the public—though not the Fed, which required proof of their objectivity—academics attempted to develop their models using the same available techniques. If academic and commercial credit systems were similar, which the academics at the time certainly thought they were, then the problems facing academic systems would also be in the commercial credit scoring systems.92 Of course, while the corporate models were secret, the academic models were not. And neither were their shocking findings.

If the antidiscrimination laws of the 1970s hoped to guarantee women and African Americans access to credit, the models developed in the early 1980s confirmed that not only would be this possible—it would be profitable. The models relied on a statistical method called “discriminant analysis” that, despite its exceedingly confusing name, grouped potential lending populations on the factors that distinguished them—without human prejudice. Using discriminant analysis, statisticians could group borrowers into good and bad default risks based on observable characteristics (like phone ownership or income) using data provided by lenders or credit bureaus.93

The great challenge, of course, was not just finding defaults and nondefaults, but revolvers and non-revolvers. These models, while better than random guessing, were not nearly as accurate as the imposing mathematical apparatus might lead one to expect. An academically constructed multidiscriminant model correctly placed 67 percent of the sample into the correct groups of revolver and non-revolver. While 17 percent more correct than a random 50-50 guess, one-third of the sample was still incorrectly placed.94 Unlike a human loan officer, such models could be objective, and ostensibly ignore protected categories. But in general, these models worked no better, and often less well, than human loan officers in differentiating between borrowers—with or without prejudice.95 A lender could still not afford to trust these kinds of models to find the sweet spot of revolvers. The risk of default remained too high.

The very groups that credit cards tended to lend to—affluent households—turned out to be the worst revolvers. The higher the level of education and income, the lower the effective interest rate paid, since such users tended more frequently to be non-revolvers.96 The researchers found that young, large, low-income families who could not save for major purchases, paid finance charges, while their opposite, older, smaller, high-income families who could save for major purchases, did not pay finance charges. Effectively the young and poor cardholders subsidized the convenience of the old and rich.97

And white.98 The new statistical models revealed that the second best predicator of revolving debt, after a respondent’s own “self-evaluation of his or her ability to save,” was race.99 But what these models revealed was that the very group—African Americans—that the politicians wanted to increase credit access to, tended to revolve their credit more than otherwise similar white borrowers. Though federal laws prevented businesses from using race in their lending decisions, academics were free to examine race as a credit model would and found that, even after adjusting for income and other demographics, race was still the second strongest predictive factor. Using the same mathematical techniques as contemporary credit models, the academic models found race to be an important predictor of whether someone would revolve their credit. But while politicians of the 1970s worried that black Americans would be denied credit on account of their race, if creditors, desperate to find revolving borrowers, read academic papers, they found exactly what they needed. Based on the data, the most profitable group to lend to, if a bank were maximizing finance charges, would be black Americans. According to research done with Survey of Consumer Finances in 1977, black borrowers were three times as likely as white borrowers to revolve their debts.100 While nonwhite, nonaffluent borrowers held out the promise of the greatest profit, even though the models circa 1980 remained inaccurate enough to base a lending program upon them. The interest rates available to lenders simply could not cover the losses that would be incurred by such lending.

For every loan, except those that will always default, there is a price that can be charged to make that loan profitable. The profit on a loan is determined by subtracting the cost of lending the money to the borrower from the price of the loan. Lenders of the late 1970s were squeezed from below by the rising cost of funds, and above by state-regulated caps on interest rates. Before lenders could pursue the sweet spot of revolving credit, lenders would have to find a way to address this squeeze. In 1978, lenders would finally have their chance.

End of Rate Caps and the Marquette Decision

Part of the reason that bankers were loathe to lend to the less creditworthy borrowers, and those more likely to revolve, was that many states capped the interest rates at too low a level to overcome the costs of default. For unsecured lending, the risks were much higher than for secured mortgage and installment lending, for which the caps had been established. The rate caps established for secured lending precluded all but the most creditworthy of borrowers from getting credit cards.

Economists of the 1970s, and today, have found it difficult to understand the appeal of interest rate ceilings. For economists, the interest rate contained no moral overtones, but was simply the price of borrowing money, taking into account the risk of the borrower and the relative demand for that money. Money was like any other commodity, and its price ought to have been set by supply and demand. For many people, however, high-interest lending smacked unethically of getting something from nothing. Profit without production seemed profoundly unnatural, as it had for centuries. But profit—not production—continued to be the ambition of the capitalists. In 1979, James Roderick, the chairman of U.S. Steel—the company most aligned in the American consciousness with real production—famously pronounced that “the duty of management is to make money, not steel.”101 If that was true for U.S. Steel, it was certainly true for Citibank. The repeal of interest rate caps, which would allow interest rates to rise to the level set by supply and demand in the market, came not from the state or federal government but from the Supreme Court—refashioning the scope of the credit card.

In 1978, in a seemingly insignificant case—now called the Marquette decision—the Supreme Court ruled that interstate loans were governed by the bank’s home state rather than the borrower’s home state.102 A Nebraska bank had been soliciting credit cards in Minnesota with interest rates above the state’s cap. The Court, in a unanimous decision, ruled that since residents of Minnesota could legally go to Nebraska and borrow money there, the residents of Minnesota should not be penalized, as Justice William Brennan wrote, for “the convenience of modern mail.”103 The National Bank Act had long allowed the interest rate to be determined by the regulations of the state where a bank was located, rather than the home state of the borrower. As the case was decided by an interpretation of federal law, rather than constitutional law, however, Justice Brennan emphasized that Congress had the power to alter the law if it desired.

In 1980, a Chase Manhattan banker predicted that the credit card, for the foreseeable future, would have a “low margin that slips back and forth between profitability and unprofitability.”104 Though the high interest rates of 1980 legitimated high interest rates on credit cards, profits were decimated by the comparably high costs for that debt, both from operations and from the expense of capital. A Federal Reserve study in 1981 found that operating costs were 46 percent of the total costs for consumer credit operations compared to 16 percent of commercial credit operations.105 If banks were paying 8 to 10 percent for deposits in the new money market accounts, as Chase Manhattan’s Paul Tongue suggested, then banks could not reduce their interest rates much further than 19 percent and still be profitable.106 As one Minneapolis banker, who ran his bank’s credit card division, remarked, “the cost of money is going nowhere but up.” For commercial banks, the problem was finding a lower cost source of funds than consumer deposits. Between the credit controls and the negative yields, many banks sold off their credit card operations to other banks, with hundreds of thousands of accounts and millions of dollars of outstanding debt.107

For every credit portfolio sold for fear of losing money, however, that same portfolio was bought. Bankers who were bullish believed that economies of scale and correct pricing could make cards profitable. While small banks, with less than $25 million in assets, averaged 203 loans per credit employee, banks with more than $500 million averaged 1,702 loans per credit employee—or eight times as many loans, substantially lowering labor costs.108 By the early 1980s, the top fifty issuers owned 70 percent of the outstanding balances. With these savings, the largest d companies could offer interest rates 4 percent lower than their smaller competitors.109 Smaller banks could do little to compete with the interest rate difference or the lower operating costs.

But even the big banks continued to lose money because of the high costs of funds. Competitive, yet profitable, pricing—fees and interest—would be the key to making credit cards profitable, but that relied on knowing the risk potential of a borrower and finding a cheaper source of capital than savers’ deposits. Citibank’s earnings fell by one-third in the first quarter of 1980, largely from negative yields in credit cards that stemmed from the high cost of funds.110 Despite 18 percent credit card interest rates, a Federal Reserve Study in 1978 found that Citibank’s woes were widespread in the credit card industry. Small banks, with deposits under $50 million, actually lost money equal to 1 percent of outstanding debt, and the largest banks, with deposits over $200 million, had net earnings of only 2.9 percent of outstanding debt. As the cost of funds increased even more in 1979, analysts expected disastrous losses and for small banks to retreat from the bank card business.111

While the Marquette decision made relocation to other states possible, the rising cost of funds made it compulsory. After the decision, large credit card issuers relocated to South Dakota and Delaware, states that lacked interest rate caps, where they could issue cards across the country. The rewards of deregulation for Delaware and South Dakota were considerable. Card receivables in Delaware grew 24,375 percent. In South Dakota receivables grew a staggering 207,876 percent. More importantly, perhaps, tax revenues grew as well, from $3 to $27 million in South Dakota and from $2 to $40 million in Delaware.112 The states acquired a new tax base, and every other state saw their sovereignty undermined by their inability to regulate credit card companies in their borders. Uber–New York Citibank moved its credit card operations to Sioux Falls, South Dakota under duress. Moving credit card operations to another state cost money. Staff had to be trained; buildings had to be found. Such moves were limited to only the largest firms, who could afford to uproot or branch their operations across the country. Smaller banks, still constrained by usury laws, in turn, felt pressure to sell their operations to larger, more efficient banks. Local politicians and customers could and did protest such moves, but without federal support were effective only for a short time. Banks like Minnesota’s First Bank System, for instance, a bank holding company of ninety-two subsidiaries, planned to consolidate all of its credit card operations in a South Dakota affiliate.113 But between bad publicity and the threat of legal action by the state’s attorney, the bank stopped. Such political and consumer pressures, however, could not end the appeal of a lack of usury rates or curb the cost of funds.

Despite scattered counterexamples, like Minnesota’s First, states were largely unable to stop the movement of big banks to deregulated states. During the next five years, two-thirds of states, including Minnesota, removed their interest rate ceilings or raised them far above market levels. Following Citibank’s move, New York, no doubt fearing the loss of other major banks, removed its usury laws. As expected, in states without ceilings, where risk and return could better equilibrate, charge-offs rose alongside interest rates. In 1984, states without interest rate controls had a charge-off rate of 1.38 percent compared to 0.85 percent in states with strict interest rate controls, as lenders sought out riskier customers.114 Consumers also equilibrated their use of credit card debt and home equity debt, as higher interest rates pushed consumers from credit cards to home equity loans. Though such practices were still not common, economists found that in states that did raise their interest rate caps, home equity borrowers tended to use more of their borrowing to purchase consumer durables, since mortgage credit was cheap relative to credit cards.115 Rate deregulation gave millions of Americans access to credit who otherwise would have been denied, but this access came at a higher price. Without rate caps, issuers could explore new, riskier markets for credit cards and Citibank, now in South Dakota, expanded its credit card operations to thirty-five states.116

Credit Cards and Class Performance in the 1980s

One of riddles of credit cards is how they fell from the height of exclusivity at the beginning of the 1980s to the depth of opprobrium by the middle of the 1990s. To have a credit card defined what it was to be rich. Take, for instance, the film Trading Places (1983), where Dan Aykroyd, as the commodity trader Louis Winthorpe III, is turned out from high society and a high-paying job after his bosses, evidently amateur sociologists as well as commodities brokers, offhandedly bet whether Aykroyd would descend to crime when deprived of his money and his social networks. After he has been turned out of the Heritage Club, arrested for drug possession, and humiliated in front of his prim fiancée, his last-ditch attempt to show that he is wealthy and upstanding is to show his credit cards to a recent prostitute acquaintance (“You don’t think they give these to just anyone, do you? I can charge goods and services in countries around the world!”) in an attempt to borrow money from her. When the cards are taken from him minutes later by a bank employee (“You’re a heroin dealer, Mr Winthorpe. . . . It’s not the kind of business we want at First National”), the last vestige of his class identity is taken away. Credit cards were the most basic tool in his performance of wealth, something without which Aykroyd most certainly could not be who he wanted to be any longer.

Credit cards in the 1980s symbolized the care-free consumption of the affluent. Instant gratification became possible on plastic. More than symbolic, however, affluence was the reality of who owned credit cards in 1980. In the early 1980s, as economist Peter Yoo points out, a household in the top decile was five times as likely to have a credit card as a household in the lowest decile.117 Today, credit cards have acquired an air of the disreputable, associated with the broke and irresponsible, but that shift occurred rather quickly during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Before its loss of status, however, credit card companies trucked on their exclusivity to expand their market shares.