CHAPTER 5

OOPS, HERE'S THE BUST

History reminds us that dictators and despots arise during times of severe economic crisis.

—Robert Kiyosaki

Bernanke's policy did not bring about a “recovery” in 2008–2009 as it was often heralded. In fact, then‐Treasury Secretary Hank Paulsen's big bank bailouts were just fuel on the fire. We call it “papering” over a problem. Print more money. Quantitative easing. Call it what you want, the American government began buying private assets off the market to prop up bank earnings and create the illusion of recovery. This period of artificial stimulation is the net cause of the historic inflation we experienced globally in 2022.

And now it is Jerome Powell's job to clean up the magma‐hot cinders. Some might even say that the global economy has yet to undo the effects of such “cheap money.” The dollar has been teetering between deflation and inflation. But before the demise of the dollar can be arrested, the causes—runaway debt and US government policy—must be addressed. In targeting “deflation” for so many years following the 2008 financial panic, the Fed actually created another one: an inflationary panic. To fight what they perceived to be a deflationary environment, the Fed left interest rates at zero for six years, from 2009–2015, all prior to the pandemic, an historic period of easy money.

In the past, US recessions arose from cheap money and excess credit. So here we go again. It's a feature, or a bug, of the Great Dollar Standard Era that the Federal Reserve has to pull levers and push buttons, publish the minutes to their FOMC meetings, and hold press releases to signal the banks what's coming down the road, direct traders on Wall Street what to buy and when and thereby “control” the economy. All for nigh? Hopefully our work here is helpful enough so you understand and don't have to worry about it… too much.

THE R‐WORD(S)

So what is a “recession,” anyway? According to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)—the official recession scorekeeper—a recession is “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months.”1 Of course, it takes time for the NBER to compile the data, so a common guffaw among writers in the financial space is the NBER will tell us we were in a recession well after the recovery is underway.

Most normal people think of a recession in terms of lost jobs, which is only one aspect of the bigger picture which involves difficulty in getting loans for homeowners, car buyers, and small businesses, and students trying to pay tuition.

The theory the Fed operates on, as we've seen aggressively in 2022, is that it can raise interest rates and squash demand for goods and services in the economy. A “recession” will slow down the economy, rein in inflation, and bring the financial system back into balance. The unnatural phenomenon here is that a recession is not necessarily something that has arisen naturally. When you pump money into the system, each dollar becomes less valuable. The only tool the Fed has to slay inflation is to dampen economic activity.

It's a necessary evil in the Fed's eyes. Its goal is to keep inflation in check by crushing consumer demand, meaning it wants to slow down people's desire to spend money. That's nuts. People change their spending habits based on the signals they get from the media and the like before the economy retreats.

Cutting back on credit when recession occurs is a form of economic dieting. We have to slim down as a result of tight money so that the economy can get back into those tight jeans it wore last summer. Most of us know exactly what that is like and what it means.

Thing is something has changed in the United States. Our economy is fast becoming morbidly obese, and we have long abandoned the desire to slim down. We just keep buying bigger and bigger expectations. We've been living in the bubble. And it's about to pop.

It became official economic policy under Alan Greenspan's tenure with the Fed not only to accept but to actually encourage borrowing and spending excesses. This occurs under the respectable label of “wealth‐driven” spending.

When we speak at conferences and talk to people around the country, we're consistently surprised at how little people actually know about the money they pack away in their wallets. Since 1913 and the passage of the Federal Reserve Act, the federal government has ceded the power over money expressly given to it by the Constitution to private interests. Article I of our Constitution gives Congress the power to coin money and to regulate its value. But that power has been delegated to the Fed, which is essentially a banking cartel and not part of Congress. This isn't just politics or stuffy economics. By allowing the Fed to have this power, we have no direct voice in how monetary policy is set, not that it would do much good anyway. The loss of sound money—money backed by a tangible asset rather than a government process—is the root imbalance that's plaguing the dollar.

To give you an idea of how the recession and recovery trend has changed, look at the historical numbers—the real numbers, not the political/economic numbers we are being fed. Early in 2007, President George W. Bush released a budget in which the ledger shifted from red to black and showed a nice surplus of $61 billion, by 2012. But—and this is a big but—it assumed real government spending growth of 0.4% a year. Bush racked up real growth at the rate of 4.6% since he took office in 2001, compared with 2.7% under Ronald Reagan and 0.8% under Bill Clinton. As the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas wrote in April 2007, “Washington's fiscal fitness remains a matter of concern… . The most recent proposal envisions eliminating them [budget deficits] within six years, but doing so will require lawmakers to overcome several significant obstacles.”2

And we all know, unfortunately, that's not likely to happen, given the fiscal leadership we've seen so far.

The peak‐to‐trough changes shown in past recessions make the point: We're not gaining and losing economic weight and returning to previous health in the same way; something has changed drastically and, like a Florida sinkhole, we're slowly going under.

That's why the dollar crisis is invisible. We really don't want to think about it, and the Fed enables us to ignore it by telling us that all is well. As long as credit card companies keep giving us more cards and increasing our credit limits, why worry? And that, in a nutshell, defines the economic problem behind the demise.

An economist would shrug off these changes as cyclical or simply as signs that in the latest recovery a bias toward consumption is affecting outcome. But what does that mean? If, in fact, we are no longer willing to accept tight money as a reality in the down part of the economic cycle, how can we sustain economic growth? How much is going to be enough? And what will happen when seemingly infinite credit and debt excesses finally catch up with us?

AMERICAN MONEY

The United States has a lot of wealth, but that wealth is being consumed very quickly. History shows that no matter how rich you are, you can lose that wealth if you're not productive. Meanwhile, the dollar's value falls and—in spite of the Fed's view that this is a good thing—it means our savings are worth less. Your spending power falls when the dollar falls, and as this continues, the consequences will be sobering.

The dollar's plunge has taken many people, currency experts of banks included, by surprise. For many of them, it is still impossible to grasp. A talking head on CNBC said that he was at a complete loss to understand how such weak economies as those seen in the European Union could have a strong currency. For American policy makers and most economists, the huge trade deficit is no problem. They find it natural that fast‐growing countries import money while slow‐growing economies export money. At least, that is the recurring theme.

So Americans traveling abroad may continue to complain that “it has become so expensive to travel in Europe” as though the problem were somehow the fault of the Europeans. But in fact, it is the declining spending power of the dollar that is to blame, and not just the French, the Italians, and the residents of the so‐called chocolate‐making countries.

This problem is pegged not to some speculative or fuzzy economic cause, even though the concept of currency exchange rates continues to mystify. A historically large trade deficit is at the core of the declining dollar. Somebody needs to get over the notion that our economy is strong and other economies are weak, merely because this is America. In the United States, the reason for the trade deficit is not a high rate of investment as we see in some other countries, but an abysmally low level of national savings. We are spending, not producing.

A second argument offered by some is that “capital flows from high‐saving countries to low‐saving countries, wanting to grow faster.” Under this reasoning, a deficit country, looking at both consumption and investment, is absorbing more than its own production. But whether this is good or bad for the economy depends on the source and use of foreign funds. Do those funds pay for the financing of consumption in excess of production (as in the United States) or for investment in excess of saving? That is the key question that ought to be asked in the first place about the huge US capital imports.

To quote Joan Robinson, a well‐known economist in the 1920s and 1930s who was close to John Maynard Keynes:

If the capital inflows merely permit an excess of consumption over production, the economy is on the road to ruin. If they permit an excess of investment over home saving, the result depends on the nature of the investment.3

The huge US capital inflows (economic jargon for money coming into the country), accounting now for more than 6% of GDP, have not financed productive investment; in fact, they are financing more and more debt. Capital grew from 5% in 2005 to more than 6% in 2006, according to a report from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), “US International Investment Position.” Our net investments are among the lowest in the world, meaning we prefer spending and borrowing over actual production and growth. The huge capital inflows have not helped finance a higher rate of investment. The United States has been selling its factories and financial assets to pay for consumption.

It's helpful to use a real means for measuring economic strength. Money coming here from overseas finances higher personal consumption. The steep decline in personal saving is a symptom of our spending, and along with that habit we have lower capital investment and a growing federal budget deficit. In the third quarter of 2005, for the first time ever, the rate actually fell into negative territory—to –1%.

The US economy has for years been the strongest in the world, leading the rest of the countries. Our Daily Reckoning newsletter routinely gets reader responses saying, in effect, “How dare you impugn the superiority of the American economy! How dare you!” We're rather thick‐skinned, so the insults bounce off rather easily. But facts are stubborn things. The fact that the US economy has outperformed the rest of the world in the past several years is easily explained: Our credit machine has been operating in overdrive nonstop. It is geared to accommodate unlimited credit for two purposes—consumption and financial speculation. Let's look at these two things a little more deeply.

Credit is not the same thing as production, despite the fuzzy logic you get from the financial media. There is a severe imbalance between the huge amount of credit that goes into the economy and the minimal amount that goes into productive investment. Instead of moving to rein in these excesses and imbalances, under Greenspan, The Fed clearly opted to sustain and even to encourage them. Under the tenure of Bernanke, and Yellen following, we wanted to believe the Fed would do better.

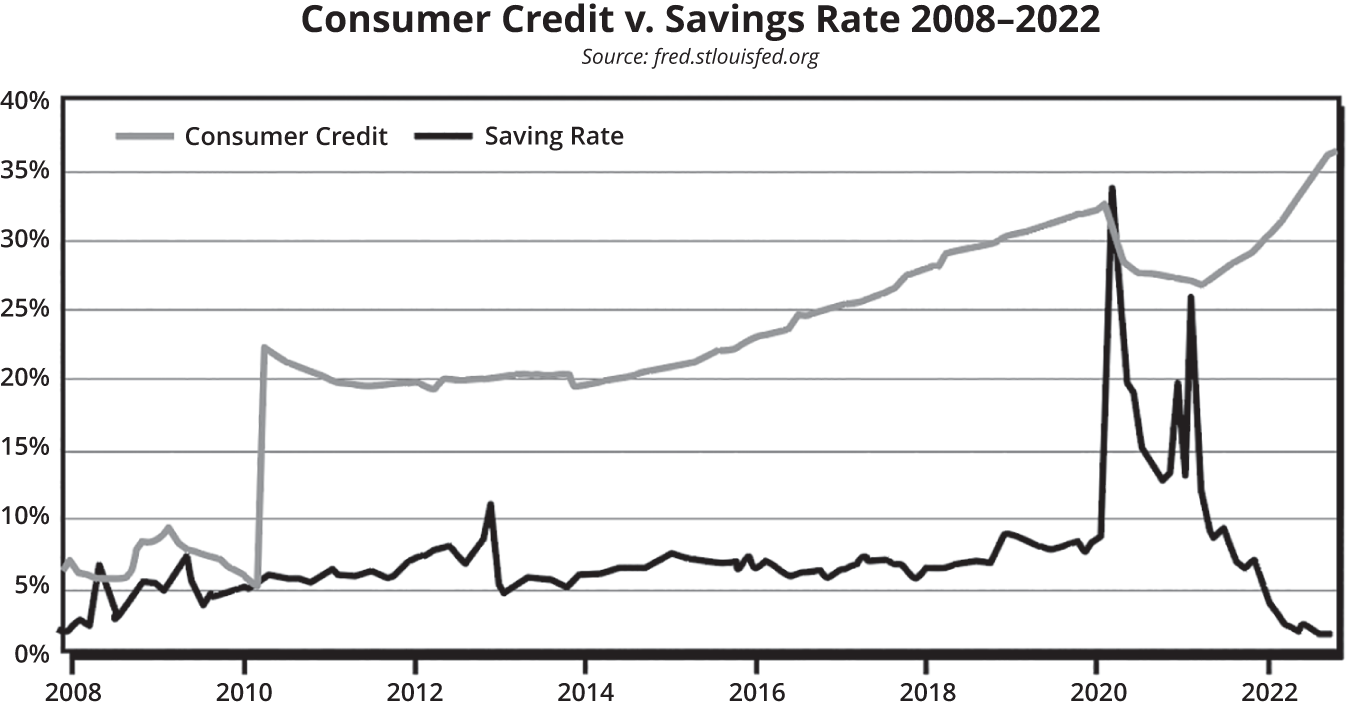

Alas, by 2021, Jerome Powell had to contend with a decade of below‐market, Fed‐set interest rates. Low interest rates encouraged increased consumer spending on credit cards and jumbo mortgages often beyond borrowers' means. Low interest rates also disincentivized saving. These economic behaviors became habitual. The average American, while feeling as though they were getting more wealthy were really benefiting from an extended era of cheap money.4

FIGURE 5.1 Consumer Credit Versus Savings Rate

Source: St. Louis Fed, fred.stlouisfed.org

You can see the spike in 2010 of consumer credit as rates were historically low. They sustained high levels until 2020, while the savings rate stayed relatively steady. The real cravings caused by the nation's credit habit began to show during 2022. As the Powell Fed got serious about fighting inflation, raising interest rates at the most aggressive pace in the Fed's history, consumers began to get squeezed. Inflation was causing consumers to use credit as a way to keep up their spending. Savings, which were already low, plummeted. (See Figure 5.1).

Low interest rates spurred a decade‐long frenzy of financial speculation too, which is equally unproductive. An “investor” puts up capital to generate a sustained and long‐term growth plan. For example, buying and holding stocks is a form of investment and a sign that the investor has faith in the management of that company.

“Speculators” don't care about long‐term growth. They want to get in and out of positions as quickly as possible, make a profit, and repeat the process. Instead of investing money to produce a product, they're interested in taking advantage of price anomalies in the market. They trade paper, not goods. So speculative profits—especially those paid for with borrowed money—tend to be churned over and over in further speculation and increased spending. None of that money goes into investment in the long‐term sense. The speculator is invested in short‐term profits, nothing more. Even so, the speculator is today's cowboy, the risk‐taking, living‐on‐the‐edge market hero willing to take big chances. He is seen as a guy with big stones because he's staring the prospect of loss right in the eye.

MAKING LESS THAN DAD

Inflation is a hard nut to crack. Most people in the job market have grown up with the expectation they'll make more and more as life and experience accumulate. Is it true?

The riddle of the next recession is not necessarily an economic one. Recessions happen. The riddle is how the next generation deals with it. Do we have the tools and wherewithal to build new products and businesses? Or are we just trying to game our way into new dollars for ourselves. A new app? Maybe. A new platform? That might work, too. The entire American economy is propped up on the idea, as my son says, to “make a fuck ton of money.” How is that going to be possible if we don't make and sell stuff? How do you make a fuck ton of money without irrational exuberance and excessive credit production? The entire economy has been handed over to the bankers and politicians. What do they care if we make stuff, or not?

The demise of the dollar and depreciation of the value of its physical aspect, i.e., the paper, has led to an obsession with accumulating wealth—greed!—without creating any value for anyone.

In past recoveries, industrial production always led the way to this idea of wealth; it was a dependable sign to measure the strength or weakness of the recovery. Production surged by an average of about 18% in the first two years after the typical recession. Since November 2001, though, when the so‐called current economic expansion began, industrial production—the creation of goods and the traditional driver of the economy—has barely moved. In fact, the total number of factory jobs lost since the start of the most recent recession in March 2001 is 2.8 million. (We have lost a total of 3.4 million jobs since 1998.) This was the single greatest percentage fall in the labor force in almost eight decades since the Great Depression of the 1930s. What has been happening to American manufacturing can only be described with the word depression. And yet this important trend is almost invisible if we look at overall GDP.

This loss in the industrial base is not a temporary thing. It is a sharp downward plunge within a longer‐term trend—going south and with the dollar's spending power soon to follow unless we turn it around. How does the loss of manufacturing jobs play into the true economic picture and, by association, the dollar crisis? Putting it another way, how is the news spun by the media?

In one headline on the topic in 2003, when the fallout from the 2001 recession was still being felt, we read: “Jobs: The Turning Point Is Here.”5 What was even more interesting in that story was a table titled “A Jobless Recovery? That Depends.” Obviously, the author wanted to convey the message that the dismal employment picture was offset by good news elsewhere in the economy. But in fact, the story's statistics only confirmed that the US economy is in a wrenching crisis. Today a more timely news headline is “Making Less Than Dad,” published on May 25, 2007, on CNN. The production side with high‐paying jobs is disappearing, while the consumption side with low‐paying jobs is booming. “There's a Job‐Market Riddle at the Heart of the Next Recession,” Bloomberg reads in 2022, and jobs are at the center again. “Tech giants and banks are already cutting workers,” they continue, “but many employers seem desperate to keep hiring.”

FICTITIOUS CAPITALISM, AGAIN

The gains in construction, commercial banking, and real estate were directly related to the housing and mortgage refinancing bubble. Look at the phenomenal growth in accommodation and services—10 times the numbers just a few years ago—and at temporary help services, which more than doubled.

What does such growth say about our real productivity? This employment record shows just how the economy's grossly distorted spending and growth pattern is moving. While the production side is collapsing, the consumption side is expanding.

Our economy is changing in big, big ways. We are moving away from goods production and toward services. It is a development that American policy makers and economists have hailed as a normal and natural shift in emphasis for a developed economy. This complacent view ignores two important points, though. First, the manufacturing sector pays the highest wages, which makes it a no‐brainer for anyone to understand—especially anyone who has lost a manufacturing job and who now works in the retail sector. Second, manufacturing is the source of earnings that pay for the overseas obligations of every country. After a slight dip in 2005 to 53%, the United States is now at the point where our exports are at only 56% of our imports (57%, if you count the gold shipped out of the country). We know that manufacturing produces more and more goods while employing fewer and fewer people. But the American case is different; the production of goods increasingly lags behind growth in personal income. But so what? How does the balance of trade affect the typical American, and how does it hurt the dollar?

We read in our media that miraculous productivity gains have become the main driver of US GDP growth. But is this for real, or is it only a big economic hoax? We may hear a variety of possible explanations. For example, businesses are supposed to be able to squeeze more value out of the average worker. As this idea boosts profits, the impending comeback of business investment spending is taken for granted. The concept of improved productivity is supposed to offset lost market share in a global sense.

Labor productivity is an economic indicator that tells us how efficiently people work. In 2004—the year we supposedly put the recession behind us—labor productivity in business, which covers 70% of all labor productivity—sank to 2.9%. And in 2005 and 2006, the drop was really alarming: 2% and 1%, respectively. That will explain why the government jumped up and down about the surge in the third quarter of 2007. But keep in mind what I said earlier about surges. They imply that things are improving. This would be true if, at the same time, average wages were growing or at least keeping pace. The claim is contradicted by the numbers. The United States is going through an employment shift away from high‐paying manufacturing jobs into low‐paying jobs, in sectors like health services and retail.

If you want to make the hair on your head stand on end, check out the numbers from a recent survey by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which studied data from the Commerce Department going back to 1929. In 2006, the share of national income that went to wages and salaries was the lowest on record. Since the 2001 recession, wages and salaries grew on average 1.9% annually, compared with corporate profits at 12.8%. In previous recoveries, wages and salaries grew at an average annual rate of 3.8%—that's nearly twice the recent rate—while corporate profits grew at 8.3%, about two‐thirds the recent rate.

The belief that productivity growth is the whole deal is delusional, but as an economic principle, it is unique to American economists. In contrast, European economists rarely mentioned the notion. They know about the importance of productivity growth, but they view it as part of a more important trend, capital investment. American economists don't like to go there because it brings up the real problem with the relationship between employment and the value of the dollar. As a rule, where there is high capital investment, high productivity growth can also be taken for granted. And by the way, capital investment also provides the increase in demand and spending necessary to translate growing productivity into effectively higher employment and economic growth.

This concept—another no‐brainer—is known to anyone who has studied history. The creation of jobs is part of the creation of infrastructure. In the United States of the nineteenth century, an era of building great railroads and canals created unprecedented economic growth and jobs. Those jobs were not created in the vacuum of a passive economy.

NICE WORK IF YOU CAN GET IT

So here we find ourselves, in the enigma of high productivity growth along with plunging employment. Why? Well, the American economists have the explanation, as always: High productivity growth goes hand in hand with jobless economic growth.

It's possible. But it might be worth pointing out that it has never happened before. It's a little like saying we can expect workers to work harder if we give them pay cuts. Higher productivity has always accompanied job creation, and that comes directly from capital investment. Old‐fashioned productivity growth also involves genuine wealth creation through the building of factories and installation of machinery. The country's most recent productivity growth had nothing to do with capital investment, sadly.

There is only one logical explanation for this contrary indicator: It must have more statistical than economic causes. If we select economics, then we have to confront the facts: There is no reasonable economic explanation for the reported trend. The doubtful accuracy in reported productivity begins with the fact that real GDP growth is vastly overstated. This is due to inflation rates that have been systematically trimmed to the downside—falsified, if you will, to present a conclusion that is just not realistic. GDP is supposed to mean growth in the domestic economy. In practice, the numbers are not only inaccurate; they are misleading.

Around the world, inflation is based on measuring price changes. In the United States, we have moved away from that idea. Our economists prefer measuring consumer satisfaction or confidence. As a result, quality improvements and the so‐called substitution effect play a key role in reducing reported inflation. Substitution refers to the way consumers alter their pattern of purchases as prices change. If beef prices rise, the consumer buys chicken. If air travel is too expensive, people drive or take a train or bus.

Our economic reporting system is like a vast national used car dealership, complete with fashion‐challenged salespeople. We are being sold a lemon. The statistical gimmick of how inflation is reported, for example, means that our actual inflation rates are understated by around 2 percentage points per year, based on how the same trend is measured in other countries. The result: overstatement of GDP.

So inflation is higher than we think, and the GDP is not growing as well as we have been told. In assessing the value of our dollars on an after‐tax and after‐inflation basis, we are losing spending power. If we use the phony government inflation number, we are not even breaking even. This problem is not limited to how our savings and investment values are being eroded. It goes far beyond the cost of milk or tomatoes.

If we look at changes in business investment, what do we find?

According to conventional reports, a great rebound in business investment spending is already in full swing, primarily in the high‐tech sector. But the so‐called investment rebound comes completely from the way we price computers. You'd have to have a Ph.D. in “statistical economics” to understand the method used by the BEA to account for price declines in the computer industry brought on by natural competition for their products.

“The inflation‐adjusted figure for investment in computers is no longer published,” is the way the BEA describes it, “because [the US Department of] Commerce was concerned the rapid price declines for computers made the figures misleading.”

Doesn't that statement seem odd? The reported rate of productivity growth comes from the potential production of computers, not from their actual use. But all the talk of the high productivity effects of computers logically relates to such effects from their use, of which we know nothing. Why? Because they are impossible to measure. The pricing of computers creates absurdly exaggerated perceptions of the money being spent and earned on computers—resulting in correspondingly higher GDP growth.

For example, under such a pricing scheme, computer producers reported an increase in revenue of $128.2 billion, or 49%, from $262.1 billion to $390.3 billion between first quarter 2002 and third quarter 2003. Very nice. But in actual dollars, the gain was only $16.4 billion, from $71.9 billion to $88.3 billion. BEA's inflated report created a boom for what was, in effect, a trickle. From an economic perspective, this contrast is huge, and the phony numbers are what most people use to draw conclusions.

Given the disparities between economic reporting and the real world, the economic importance of high‐tech industries has been and continues to be overhyped in the United States. In terms of sales, employment, and earned profits, it is a sector of minor importance. The high‐tech profit performance has been abysmal. Remember the industrial revolution and its lessons. Implementing new technologies involves radical changes across the economies, requiring and creating huge new industries with soaring employment. It radically changes economic and personal life. Is our so‐called technological revolution a new industrial revolution? Hardly. By comparison, the new high‐tech industries—what Andy Kessler refers to as the iPod Economy—are marginal. At the very least, measuring production based on these sectors is deceptive.

Under the official methodology—meaning reports from the government and from the official National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA)6— the profit picture is impressive. But a variety of profit studies tell a different story. Most economists have a great liking for the most comprehensive figure: corporate profits with inventory valuation and capital consumption adjustments. This is a fuzzy number. For one thing, it obscures what is really going on in the trend, as it includes the financial sector and now exceeds $1.6 trillion. Since their lows during the recessionary years, the aggregate numbers have grown by about 60%. But including the financial sector is a problem.

In what we may term the “real economy” (i.e., excluding the financial sector), the numbers are quite different. This nonfinancial real economy experienced pretax profits at a low of $357.2 billion in 2001 from a peak of $573.4 billion in 1997. Even with gradually increasing reported profits through 2006 (reaching $814.3 billion by the third quarter) the numbers remain, well, flat. This is true when we look at manufacturing alone, where we find that the numbers are no higher than they were in the previous decade. The gain for the nonfinancial sector has overwhelmingly come from retail trade, and we have to confront what this means in terms of jobs as well as profits. When we compare typical manufacturing profits and see a decade‐long flat line, it is difficult to justify claims of an improved economy.

TIKTOK, TOILET PAPER, AND INFLATION PSYCHOSIS

The companies that were able to provide goods and services during the pandemic, while everyone was home, saw stark increases in S&P valuations. Everyone went online; everyone wanted to buy stuff without leaving their beds; people were in desperate need of entertainment—and toilet paper. Netflix, Amazon, Meta (then Facebook), and TikTok. The pandemic created an economic aberration we're all familiar with; one which, in late 2022, no one really knows what to make of yet. It's hard to build a business when you can't read the tea leaves while being forced to sit on your couch. We do want to make it exceptionally clear, however, that the inflation we are seeing today is not the result of coming out of our hidey‐holes; rather, it is the result of the cheap money bailout extravaganza that happened from 2009–2018. The pandemic was just the icing on the cake.

This economic aberration in our reported GDP numbers—what politicians have generously called growth—is a bubble‐driven spending surge. Initially, the emotional experience of the pandemic gave a boost to profits for S&P 500 companies as everyone was locked in and shopping online. Income‐driven spending derives from wages and salaries, which—from another point of view—are also business expenses. In contrast, credit‐financed spending increases business revenues.

Now we apply the same logic to what happens in the economy as a whole. Just as a corporation is limited in how far it can improve its bottom line, the consumer is also subject to economic laws. What turned cost cutting of the past few years into profits for businesses was a debt‐driven economy. Consumers increased their spending despite heavy losses and funded it through higher borrowing.

NOTES

- 1. “How Do Economists Determine Whether the Economy Is in a Recession?” n.d. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2022/07/21/how-do-economists-determine-whether-the-economy-is-in-a-recession/#:~:text=The%20National%20Bureau%20of%20Economic,committee%20typically%20tracks%20include%20real.

- 2. “Fiscal Fitness: The U.S. Budget Deficit 's Uncertain Prospects, ” Economic Letter—Insights 2, no. 4, April 2007, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

- 3. Joan Robinson, “Reconsideration of the Theory of Free Trade,” Collected Economic Papers, Volume IV, 1973.

- 4. Tyler Durden, “The US Consumer Has Cracked: Discover Plunges after ‘Shocking’ Charge‐off Forecast,” ZeroHedge, 2023. https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/us-consumer-has-cracked-discover-plunges-after-shocking-charge-forecast?utm_source=&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=1202.

- 5. BusinessWeek, October 27, 2003.

- 6. To view recent NIPA data, check the BEA web site at www.bea.doc.gov/bea/dn/nipaweb/SelectTable.asp?Selected=Y.