CHAPTER 8

ALAS, THE DEMISE OF THE DOLLAR

When written in Chinese, the word crisis is composed of two characters. One represents danger and the other represents opportunity.

—John F. Kennedy

The global economy is continuing to change, as it will. The US dollar remains on the front lines of change as its reserve currency, for now. When we take a look at history, we see how past events have affected everything. The Black Death created a devastating labor shortage throughout Europe for decades. Christopher Columbus's voyages turned trade upside down for hundreds of years. The industrial revolution moved economic power in ways that continue to affect economic balances to this day. And now we face another great shift, away from US dominance of world markets and toward new leaders—China and India.

The economic reality—a type of geography—is changing. As a consequence, real estate speculation in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles may be replaced with more global interest in the new real estate markets—in Beijing, Shanghai, and Bombay. Who knows? We can only anticipate how changes will occur based on what we observe today. Does this mean the age of America is ending? No, it simply means that economic muscle will be flexed by someone else in the future. This is a trend. And like all trends, they are more easily viewed in historical perspective but harder to judge from their midst.

When we look at trends in dollar values, we can observe that incomes have not declined. That's great. But we also see that prices have risen faster than incomes. So with decreased buying power (caused by this disparity) we have seen a decline in income in terms of what really counts. It takes more dollars to buy the same thing (in other words, prices are higher), but incomes have not risen to meet that price inflation. That's what happens when the value of the dollar declines.

Economic history is a history of bubbles—and of bursts. The great disservice being done to Americans by the financial media is that they are not being offered the opportunity to learn from what is going on. They are losing buying power, but apart from a few painful spikes at the gas pumps and in grocery lines, it's invisible.

In the Great Dollar Standard Era, the problem is global. While there is, of course, more to it than just the value of the US dollar, here is how it works. Fake money creates fake demand.

The global economy is interconnected. Even as early as the 1930s, we saw the impact of how an economic challenge in the United States could create a worldwide depression. The Great Depression resulted from multiple causes, but most notable among them were two things: a huge transfer of funds from World War I reparations and far too much credit that went beyond the borrowers' ability to repay. All of that credit—essentially, funny money—also created a fake demand. We see the effects of this policy in housing as severely as anywhere.

The whole mess is traced back to the origin—a Fed policy encouraging debt spending as a means to artificially create the appearance of productivity.

It has always been an effective policy to raise rates to slow down inflation, just as lead rods are moved into the radioactive core of a reactor to cool down the chain reaction. Higher rates put a damper on spending. This has been recognized widely, so the Fed policy—based on the idea that lower rates are “good for the economy”—is without merit. In fact, it is damaging. The housing market and the mortgage bubble bursting in 2008—and the following subprime mortgage mess and credit crisis—were the first victims of this policy and the most visible.

Then the Fed persisted and insisted on keeping rates below market value for another decade. The trouble with the Fed keeping rates low as long as it did after the crisis had been averted was that it wasn't prepared for the next crisis when it would invariably hit. In our lucky case, it was a global virus that, through a concerted worldwide policy effort, shuttered the entire global economy.

THE WEAKENING DOLLAR AND ITS EFFECT ON THE ECONOMY

In the first edition, we said that the day was surely coming when foreign investors will reach a limit in their willingness to buy US debt, thus financing our deficit. The finance minister of India hinted as much in late 2004. South Korea, too, made overtures for reducing the amount of US dollars it holds in reserve. Well, that day arrived. In August 2007, the central banks of Japan, China, and Taiwan sold US Treasuries at the fastest rate in as many as seven years. Taiwan cut nearly 9% of its Treasury holdings, its biggest sell‐off since 2000. China shed more than 2%, its biggest move since 2002. And Japan dumped 4% of its US Treasuries, its largest reduction since 2002.

A few months later, in November 2007, the US Treasury's TIC data revealed that Japan, China, Caribbean banking centers, Luxembourg, Hong Kong, South Korea, Germany, Singapore, Mexico, Switzerland, Turkey, Canada, the Netherlands, Sweden, France, Russia, Ireland, and Israel were all net sellers of US Treasuries in September. For three months in a row, Japan and China—the world's largest holders of US government debt—were sellers of such Treasuries. They now hold less than $1 trillion in dollar reserves. The central banks of these countries will conclude that it's smart to move their funds into other currencies—or to demand higher returns on their money.

We have all heard of denial—that self‐protective tendency to contradict the obvious truth. Well, our federal policy makers are suffering from denial. Drunk on the power of the dollar and heedless of the damage it does to print more and more currency, our leaders have convinced themselves of something: that if the dollar's value falls, that will eliminate the trade deficit, reduce inflation, and improve our GDP. Just as onetime fiscal conservative Richard Nixon decided to try wage and price controls to solve the economic problems of 1971 and then took the US economy off the gold standard, this new but illogical plan will also fail.

The United States has seen little to low growth in manufacturing (defined in terms of number of jobs, output, or profits) in more than 20 years. Changing this situation is the only solution to the trade deficit. In other words, we have to compete. We cannot trick the economy into coming into line by reducing the value of the dollar. It was possible on the gold standard to control economic trends to a degree. But we cannot simply look for easy solutions. Destroying our own currency's buying power is not the answer.

In fact, before we actually lost our trading dominance, the dollar wasn't worth too much compared to other currencies. Nixon's economic decisions were based on the realization that some prices were unrealistically low, coupled with the fear that not correcting that problem could cost him re‐election. Unfortunately, he did not stop with wage and price controls and a tariff surcharge. He proceeded as though the problem had been created by the dollar, and that simply was not the case.

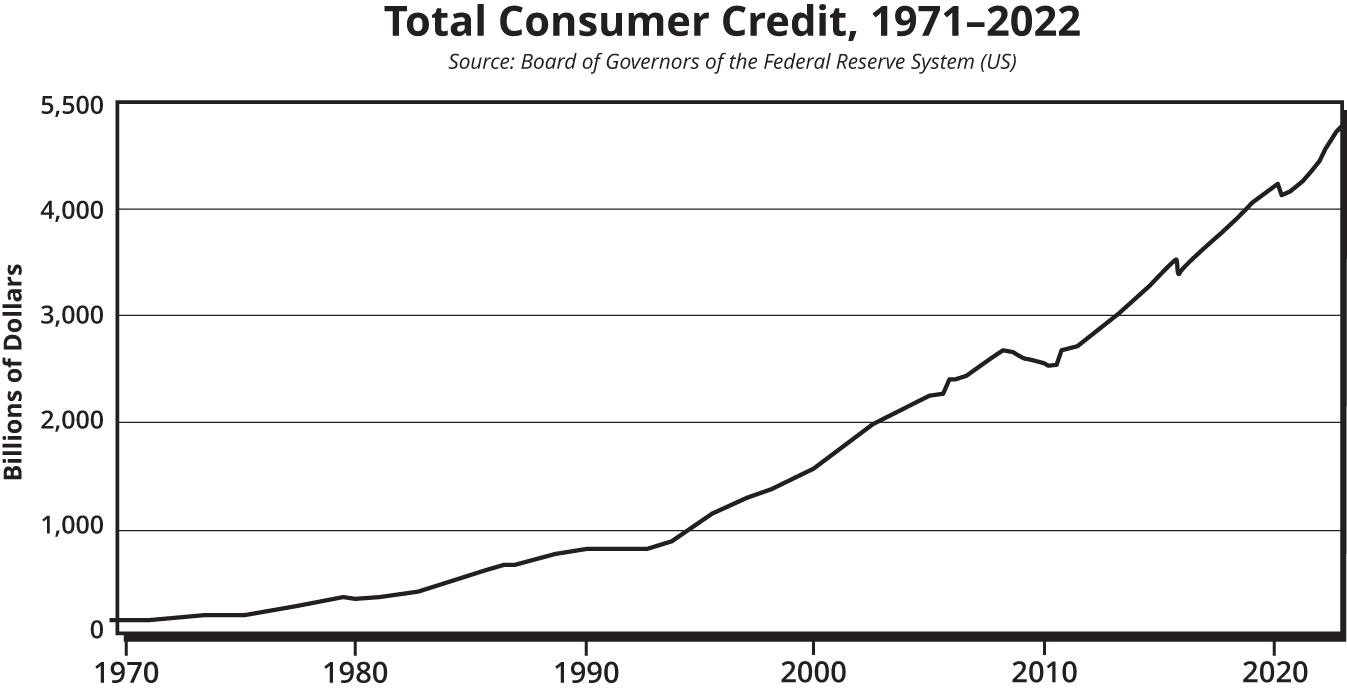

Between 1984 and 1994, total consumer credit in the United States grew from $527 billion to $1.021 trillion (almost doubling in the decade). From 1994 through 2007, the debt rose to $2.480 trillion, doubling again at an accelerated rate. Check the graph in Figure 8.1.

In the years from 1984 to 1994, the average annual growth in consumer debt was $49.4 billion per year. In the next decade, though, the average rate was $108.3 billion and moved upward year after year at that faster rate. In the third quarter of 2007, consumer debt pushed close to $2.5 trillion—a 25% increase in less than three years. But that's only the tip of the proverbial iceberg: The real danger lies in the credit crisis beneath the surface.

It's eerie—in December 2004, we ran the playfully facetious headline, “The Total Destruction of the US Housing Market.” Little did we know how right we were. The crux of our argument at the time was that Fannie Mae, the nation's biggest—and government‐backed—enabler of the subprime mortgage market, was in trouble. We retell it here as a cautionary tale.

Internally, Fannie Mae had published a report revealing the firm's exposure to the derivatives market. The author of the report was reprimanded and fired, and the report mysteriously disappeared from the internet. Fannie had been engaged in Enron‐style accounting. Heck, it even used Arthur Andersen as its accountant—the same firm used by Enron. Congressional hearings followed, but all was soon completely forgotten—until the news surfaced about the fallout with Freddie.

FIGURE 8.1 Consumer Credit Outstanding, 1971–2022

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US)

Until the secondary market for mortgage‐backed securities started drying up over the summer of 2007, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae—which own or guarantee about 40% of the $11.5 trillion residential mortgage market in this country—were the reliable sources of credit that kept the pulse beating. Now Freddie is telling us that if conditions continue to deteriorate, it may have to purchase fewer mortgages, which would take even more homebuyers out of the market.

As if on cue, the worst home sales report of all time was issued the same day. Existing home sales fell 20% in October 2007 from the previous October, to an annual rate of 4.9 million, the lowest ever recorded by the National Association of REALTORS® (NAR). October also marked the 15th out of the past 17 months in which this price measure posted a year‐over‐year decline. And wouldn't you know—a record level of homes are now sitting in inventory, a whopping 11‐month supply.

Given the massive acceleration in rate of credit expansion, it does not seem likely that a falling dollar is going to fix the problem of the trade deficit. This credit money, which is not backed by anything, can best be described as “magical, out‐of‐thin‐air fairy dust money.”1 One saving grace in today's economy is that our trading partners and competitors are in bed with us, economically. In the 1980s, overseas dollar‐based assets held by foreign interests were practically at zero. Today, those holdings have ballooned to about $16.295 trillion. So our fortunes—including the value of the dollar—have ramifications for heavily invested foreign central banks and private interests.

THE THREAT OF INFLATION—OH, WAIT, IT'S HERE

The United States has enjoyed such low inflation for many years (compared to the late 1970s, at least) that many Americans came to believe that inflation was a thing of the past. Ironically, some people even credited the Fed and its monetary policies with controlling or ending inflation.

This is 180 degrees from the truth. We have inflation, but the credit‐based economy and liberal monetary policies of the Fed kept inflation pent up. Experience and history both tell us that these aberrations eventually become realized, usually with a vengeance. And that's exactly what we saw during and following the pandemic (See Figure 8.2).

FIGURE 8.2 Inflation in the United States, 2013–2022

Source: usinflationcalculator.com

We have to remember that inflation and the falling dollar are in fact the same thing, but expressed in different ways. So the Fed's policies are designed to keep interest rates and inflation down while encouraging consumer debt to rise—all on the premise that this will stimulate investment and growth. At the same time that the Fed wants to continue to see a falling dollar, it claims it is fighting to ward off inflation. The two goals are at odds with one another.

The financial media got in the habit of listening to Bernanke during his tenure. Yellen continued the now Nobel‐prize‐winning economist's logic. He had a way of framing bad news that is reminiscent of many corporate annual reports. Their philosophy that economic news must always be expressed in positive tones tends to obscure what is really going on. And did so for more than a decade. It wasn't until Jerome Powell was faced with near double digit inflation that the Fed tone changed. We haven't found any evidence where the Fed governors have taken accountability for causing the inflation they're now hawkish about battling.

In December 2006, Bernanke traveled to Beijing to talk to the Chinese about their economy. He duly noted China's “impressive rate” of growth, of 9% a year from 1990 to 2005.2 But that's nothing compared to the growth in trade that occurred after China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, when the dollar value of exports started growing at an average annual rate of about 30%. Add in capital inflows—particularly foreign direct investment (FDI), which leaped from $2 billion in 1986 to $72 billion by 2005—and you're looking at a pretty robust picture.

But there's a flaw, Bernanke told his audience: The Chinese are investing and saving too much. Approximately 33% of their GDP goes into fixed business investment, and the national savings rate is way into the ozone, at 52%—compared to our now below‐zero rate. That kind of behavior is contributing to “global imbalances,” the Fed head told the Chinese gravely. The solution: Increase monetary and social policies “aimed at increasing household consumption.” In other words: Get debt.

It's amazing just how much Bernanke, then Yellen after him, sounded like the old bespectacled boss. In fact, the Greenspan era, which lasted from 1987 to 2006, set the stage for everything we saw and heard for the ensuing 12 years. To understand just how important Alan Greenspan's influence was, it's helpful to reread him.

In January 2004, Greenspan explained that our trade gap with China (while still a deficit) had narrowed. He explained that “following a shortfall of $41.6 billion a month earlier … the trade deficit with China narrowed to $10.8 billion from $13.6 billion.”3

Great news, Mr. G. The Fed chairman's policy of “salvation by devaluation” was reflected momentarily in reduced trade gap numbers. But are these truly related? While reducing the dollar's value is unavoidably inflationary (by definition, a lower dollar is inflation), it boggles the mind to accept Greenspan's argument. In essence, he claimed that inflation creates lower trade deficits. He has never admitted that a devalued dollar and inflation are the same animal, but anyone who has survived an Economics 101 class knows that it is. We have cleaned up inflation by calling it something else. We have put lipstick on the pig and called it by another name.

In fact, Greenspan shrugged off concerns about the falling dollar. He said that he expected current global currency imbalances would be easily diffused with little or no disruption.4 He referred to flexibility in international policy as the key to this easy fix. On January 13, 2004, Greenspan spoke in Berlin: “The greater the degree of international flexibility, the less the risk of a crisis.”

He also set up the European economies as the fall guy for the effects of the falling dollar, thus a rising euro, saying that any protectionist initiatives among European nations would erode the flexibility. In the same talk, Greenspan—perhaps in a fit of denial?—commented that US current account deficits were not a problem. Here again, he obscured the relationship between a falling dollar and inflation, stating that it was true the US dollar had fallen against other nations' currencies, but at the same time inflation “appears quiescent.”

Greenspan's cryptic warning concerning where this all goes contradicts his claim to a quiescent inflation. He went on to explain that if the current deficit were allowed to continue, “at some point in the future further adjustments will be set in motion that will eventually slow and presumably reverse” demand from foreign investors for US debt, a prediction that looks very possible lately.

At that time, the US trade deficit sat at about 5% of GDP. Greenspan shrugged this off as well, even in the face of rising deficits over time. He claimed that financing the US debt with US dollars would, in essence, expand the US ability to carry debt. Or, putting it another way—if we understood Greenspan correctly—our dollar is so popular that it serves to increase our international line of credit. This sounds like the policy of deficit spending—no big deal, apparently—should only continue and expand.

In fact, Greenspan's opening statement during his January 2004 speech is amazing in itself:

Globalization has altered the economic frameworks of both developed and developing nations in ways that are difficult to fully comprehend. Nonetheless, the largely unregulated global markets do clear and, with rare exceptions, appear to move effortlessly from one state of equilibrium to another. It is as though an international version of Adam Smith's “invisible hand” is at work.5

The “invisible hand” was Adam Smith's metaphor referring to an economic principle of “enlightened self‐interest.” The theory supports a contention that in a capitalist system, the individual works for his own good, but also tends to work for the good of the nation or community as well:

Every individual necessarily labors to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. He intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for society than if it was no part of his intention. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good.6

Greenspan latched onto this argument, made originally by Smith to argue against regulation and protectionism in markets. But the unintended consequences of the principle are disturbing if, as Mr. Greenspan claims, the international monetary situation depends on governments doing less rather than more. The Fed chairman had more praise for Adam Smith a year later in the Adam Smith Memorial Lecture in Fife, Scotland. He described Smith as “a towering contributor to the development of the modern world.” He expressed the belief in Smith's principles of an unregulated market, in an apparent reference to modern trends in international trade and notably China. Greenspan said, “A large majority of developing nations quietly shifted to more market‐oriented economies.”7

Let's not forget, it was the United States that went off the gold standard—arguably to remove the restrictive nature of pegging money to gold, but in practice to enable a planned intervention in international trade by expanding the dollar. That in itself was and still is a form of protectionism, the very thing Greenspan argued against. If US policy was truly faithful to the idea of unregulated international monetary policy, it would have left the gold standard in place, recognizing it as a means for curtailing runaway inflation, jarring monetary disparities, and—as we now have—huge deficits. In spite of the Fed theme to the contrary, printing money and creating a debt‐based economy is contrary to Smith's hypothesis.

Greenspan had a theory about the huge US current account deficits. But he dismissed it in one respect by pointing out that deficits and surpluses always balance out:

Although for the world as a whole the sum of surpluses must always match the sum of deficits, the combined size of both, relative to global gross domestic product, has grown markedly since the end of World War II. This trend is inherently sustainable unless some countries build up deficits that are no longer capable of being financed.8

Hmm. As in the case of the United States perhaps? What Greenspan is saying here is that growing deficits are no problem unless they get so large that the lender nations—those with net surplus dollars—are no longer willing to carry the debt. This is clearly the simplest method by which to judge a nation's economic health. If the size of the current account deficit has gotten too large, it is easy to see that the country is living beyond its means—and the trend cannot continue without dire consequences. However, it appeared that Greenspan was not aware of this. He continued:

There is no simple measure by which to judge the sustainability of either a string of current account deficits or their consequences, a significant buildup in external claims that need to be serviced. In the end, the restraint on the size of tolerable US imbalances in the global arena will likely be the reluctance of foreign country residents to accumulate additional debt and equity claims against US residents.9

In fact, as Greenspan pointed out in the same speech, the trend is certainly heading to that obvious but dire conclusion. He noted that by the end of 2003, net external claims had grown to about 25% of US GDP, with average annual growth continuing at 5% per year. But, he contends, “the sustainability of the current account deficit is difficult to estimate.” Why, we wonder, is it so difficult? Greenspan double‐speaks by explaining that US capacity for increased debt is “a function of globalization since the apparent increase in our debt‐raising capacity appears to be related to the reduced cost and increasing reach of international financial intermediation.”10

Well, that statement makes no sense, but here's what really matters. Any American who holds a mortgage knows where it goes if he or she keeps borrowing on the equity. Your bank wants you to have 20% equity in your home, for example, but you sign up for a series of additional mortgages, a line of credit, and refinancing of your paper equity. At some point your debt is 125% of equity, and then what? Will your lender institute some form of “financial intermediation” by saying, for example, “no more debt”? If a lender draws the line at that point, then your capacity to borrow will be stopped. This is where the US debt trend is going, and Greenspan admitted as much in the statement (even though no one can be sure about what he really meant).

Greenspan seemed to earnestly believe in his theme, that “market forces” would work in a flexible world economy to make everything all right. Does this mean the deficits will simply disappear? No, but it does imply that the level of deficits is acceptable given those very market forces—and that these levels will become even more acceptable in the future. Somehow. It's a matter of flexibility in his view that will lead to this improvement in the state of US debt. He said:

Can market forces incrementally defuse a worrisome buildup in a nation's current account deficit and net external debt before a crisis abruptly does so? The answer seems to lie with the degree of flexibility in both domestic and international markets. By flexibility I mean the ability of an economy to absorb shocks, stabilize, and recover. In domestic economies that approach full flexibility, imbalances are likely to be adjusted well before they become potentially destabilizing. In a similar flexible world economy, as debt projections rise, product and equity prices, interest rates, and exchange rates could change, presumably to reestablish global balance.11

And if only the rest of the world would go along with US policy in other regards, we could all have peace and prosperity. But that isn't going to happen. It's more likely that the invisible hand is going to slap us across the face with a monetary rude awakening.

Greenspan refers to the “paradigm of flexibility” in a stated desire to see exchange rates stabilize. But doesn't that sound like what Nixon was trying to accomplish in 1971 by going off the gold standard? To any extent, what he was trying to accomplish didn't work. It only led to the current mess in terms of the trade deficit and the falling dollar.

Greenspan's speech was revealing, not only in demonstrating his economic philosophy but also in showing his view of how economic forces work. His dismissal of growing debt as a significant force ignored the important differences between spending borrowed funds and investing borrowed funds. Apparently he didn't believe the distinction to be an important one, and neither does his successor. The problem is—and it's a big problem as 2007 draws to a close—the fiscal environment has changed. Inflation is much more of a threat, but Bernanke doesn't have the luxury of following in Greenspan's footsteps. In fact, Greenspan said so to USA Today in an interview published on September 14, 2007, to promote his autobiography. “We had the luxury of not worrying too much on the downside.” But now, “That luxury is gone. So Ben [Bernanke] is going to have a tougher time, more difficult decisions, than I had.”

INFLATION BY ANY OTHER NAME

If you define inflation as an expansion of the money supply (which, of course, devalues the dollar through dilution, at the very least), you need to also look beyond this definition. We are facing a new kind of inflation: price inflation.

Higher prices are a reflection of decreased purchasing power of our dollars. It is academic to argue which method of explanation is more accurate. Under widespread price inflation, it takes more money to buy the same stuff.

We should not ignore the extreme hyperinflation of Germany in the 1920s as an example of how bad things can become when inflation gets out of control. In January 1919, an ounce of gold cost 170 German marks. Less than five years later, the same ounce cost 87 billion marks. The hyperinflation affected everything, even postage stamps. We have seen a similar type of inflationary effect in many other countries. Toward the end of the USSR empire, a worker was interviewed in Moscow during a time when some employers were paying workers in clay bricks rather than currency. When asked about the situation, a worker told a reporter, “We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.”

A devalued currency—or, in the extreme, a worthless currency—is going to affect where and how we invest. It will affect far more than prices, perhaps requiring everyone—even the securely delusional American consumer—to rethink the whole attitude toward money, spending, and debt.

As we've noted, one important sign of the weakening dollar and currency inflation is seen in the price of gold. Tracking gold prices is a reliable way to gauge what is going on with currency values, because the tendency is for gold's value to rise as the dollar value falls.

A historical example from the last period of dollar weakening will help us here. Following the great Tech Wreck, the crash in tech stocks that began March 10, 2000, when the Nasdaq stock market index peaked at 5,132.52, gold began to rise off its 1999 low of $253. By 2003 the price rose above the magic $400 per ounce level for the first time in eight years. By 2004, the gold price had grown 25% in one year and was up 60% from its low point in 1999. Almost as good as gold is the opinion of those in the know, such as Warren Buffett. In 2003, for the first time in his life, Buffett began buying foreign currencies—to the tune of $12 billion by year‐end. He cited continuing weakness in the US dollar as the reason.12

By the beginning of 2005, Buffett was still betting against the dollar. His foreign currency holdings increased to $20 billion. At the time he began buying up overseas currency, the euro was worth 86 cents to the US dollar. By January 2005, the euro traded at $1.33, an improvement of more than 50%, and it continued its upward climb. So is Buffett smart to change his strategy? In the first three quarters of 2004, his company, Berkshire Hathaway, netted $207 million on currency speculation—not bad. Looking back at the fall of the dollar against the euro—33% between 2002 and 2005—it would seem that Buffett's timing was great. Since 2002, he has scooped up $2.2 billion for his shareholders. In his famous plain‐speaking way, he explained his concerns about the value of the US dollar: “If we have the same policies, the dollar will go down.”13

In fact, Buffett told us in person recently, “If the current account deficit continues, the dollar will be worth less 5 to 10 years from now.”

“Insanity consists of doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result,” quoted the sage. “In the United States, the cause, in my view, of the declining dollar in very major part, is the current account deficit, and the trade deficit being the biggest part in that.” He went on to say, “I don't know what it will look like in any short term, but I would say that force‐feeding a couple billion a day to the rest of the world is inconsistent with a stable dollar.”

In a Q&A session with the Financial Post, Buffett admitted he had made “several hundred million” bucks buying Canadian loonies over the past year, a position that he also admitted he regretted leaving.

Today, Buffett says he currently owns only two currencies: the embattled greenback and Brazilian real. The dollar, suffice to say, hasn't been treating him well. Buffett didn't disclose when he bought reals, so we can only guess how he's done on that one.

Buffett's change to foreign currencies is significant. When the Oracle of Omaha does something he has never done before, it's worth noting.

Why, though, has he decided on this big shift now? Buffett is concerned with the huge (and growing) balance of payments deficit. Foreign investors hold $9 trillion in US debt, consisting of bonds and other debts. He sees the day in the not so distant future when this buying spree will end. Because the US economy depends on continued overseas investment (as a means of financing our debt economy), any slowdown in the volume will result in further weakening of the dollar. In other words, it can't go on forever.

Buffett isn't the only guru who saw the problem in clear terms. George Soros, Sir John Templeton, Jim Rogers, and Bill Gates all agreed. In other words, many investment luminaries known for their good timing and vision are in agreement that the dollar is in big trouble. In a nutshell, a weakened dollar is a relative matter, so it means that other currencies will perform better and will strengthen. Even Alan Greenspan knows that all things equal out, whether trade imbalances, deficits and surpluses, or currency values.

THE FED'S PREDICTABLE COURSE, REVISED

Fed policy is, in fact, an intrinsic part of the path toward a falling dollar—not only by inevitable consequences, but as part of a stated federal policy. The Fed wants the dollar to fall, in theory and in practice. It's easier to pay off debt if there are more dollars in the system, even if that means the dollar buys less for you. Jerome Powell, as the chairman of the Fed, has been making bold statements about raising rates until inflation is under control. But with the debt situation the government has gotten itself into, it actually makes sense to inflate the currency. In past economic practice, allowing interest rates to rise was the effective means for curbing excess spending. Today, spending isn't viewed as a problem. A review of Fed history explains how we've gotten to this point.

As we've noted, the Federal Reserve was first suggested in 1907 by Paul Warburg, publisher of the New York Times Annual Financial Review. Warburg suggested the formation of a central banking system to help deter panics. One of Warburg's partners, Jacob Schiff, warned the same year that lacking such a central bank, the country would “undergo the most severe and far reaching money panic in its history.”14

They were both right in their prediction. The infamous Panic of 1907 hit in October. The idea that panics were caused, at least in part, by lack of strong central banking controls continues to find considerable support. Even Milton Friedman (with Anna J. Schwartz) is on record in believing that the Great Depression was as severe as it was primarily because the Federal Reserve mismanaged the nation's money supply.15

To help us sum up, we need to review the responsibilities of the Fed to understand where we are today. The Fed was authorized to undertake three primary roles: supervise and regulate banks, implement monetary policy by buying and selling US Treasury bonds, and maintain a strong payments system. Operating as a central bank (organized with its 12 regional reserve banks, a Board of Governors, and the Federal Open Market Committee), the Fed has expanded beyond its original mandate. Consider the second and third roles: to implement monetary policy by buying and selling US Treasury bonds and to maintain a strong payments system.

Today, the Fed certainly implements monetary policy. The Fed controls interest rates as a means of determining the value of the dollar and—in spite of the rather restrictive original definition of how the Fed was to implement policies—it does much more today than buy and sell Treasury bonds. A “strong payments system” may have had a relatively restrictive meaning in 1913, and we have to wonder what members of Congress would have thought about the original bill if they could see our economy today. Given the widespread isolationist view in that period, it is doubtful that Congress would have been willing to give over the power to the Fed to influence currency exchange values throughout the world. It would have been interesting to see how differently US monetary policy would have developed if the original bill had also tied the Fed's actions into a requirement that the United States remain on the gold standard. Alas, history is moved by conundrums. The dollar just happens to be one of the biggest, most challenging conundrums in financial history. And just happens to have come on our watch.

What is real money, then, in an inflationary period? This question should be on the minds of every investor and everyone who observes what happens at home and abroad. The US government has done an excellent job of convincing us that all of those dollar bills being exchanged work as actual money. In fact, though, everyone knows they have no tangible value. They are backed only by (1) a promise by the government to honor the debt and (2) assurances from the government that the money does have value, that one dollar is worth one dollar.

Both of these promises are questionable. How can the government promise to pay its debts when the total of that debt keeps getting higher and higher? It's already out of control. And in our fiat money system, the implied promise that a dollar is worth a dollar has to be looked at with suspicion as well.

This is not just an exercise in economic theory. The near future could prove to be a financial disaster for anyone who continues to have faith in the strength of the dollar. In fact, a collapse is inevitable, and it's only a question of how quickly it is going to occur.

The consequences will be huge declines in the stock market, savings becoming worthless, and the bond market completely falling apart. As the value of the dollar falls, that dollar will no longer be worth a dollar; it will be worth only pennies on the dollar. It will be a rude awakening for everyone who has become complacent about America's invulnerability.

The monster lurking in the near future has been caused by government policy. Our leaders have allowed foreign interests to take control of our economic destiny, and we cannot necessarily count those foreign interests as allies. We are not threatened by imminent invasion or loss of freedom to move about, but the extravagant American standard of living is about to be changed, drastically and suddenly. This has come about by three changes in fiscal status. First, the strength of the dollar and the level of interest rates are no longer in the control of the Fed. Second, good jobs have been sent overseas, and the so‐called recovery has consisted of low‐paying jobs. Third, because average wages are falling, Americans cannot afford inflation; even with our increasing credit card and mortgage–based bubble economy, the illusion of prosperity cannot go on forever.

HOW TO LOSE CONTROL OVER THE VALUE OF YOUR MONEY

The Fed has decided that nothing can ever stop the US economy. Continued growth is inevitable and—the ultimate delusion—our officials appear to truly believe that they can control it. If the economy slows, no problem. The Fed has declared lower and lower interest rates as a means for encouraging more and more debt—and that is called sound policy.

It's not just the consumer who has spent beyond his means. The government has led the way by bad example. US borrowing has expanded to the point that foreign central banks own major portions of the US debt. The Bank of Japan held $668 billion of Treasury securities in 2004, compared to the Federal Reserve holdings of $675 billion. In other words, the Bank of Japan nearly matched the Fed in ownership of US debt.16 (Shortly after the first edition went to press, Japan began cutting its holdings, down to $582.2 billion as of September 2007—less than the debt the Fed owns, at $666.4 billion. If you just add in China, South Korea, and India, the Asian central banks own a lot more debt than the Fed does.)

With so many Asian currencies tied to the dollar, isn't it in their interests to keep dollar values high? Yes, but only to a point. Asian central banks will ultimately allow the US dollar to fall to contain inflation in their own countries. And the more debt those central banks control, the greater their control over the US dollar—and over the standard of living in the United States.

Should we fear global inflation? Again, we have to take into consideration the anomaly caused by the pandemic and the slowdown it caused in the Chinese economy, but it's worth noting that in 2022, China still had a growth rate greater than 3.6%.

Across the globe, in 2022, India, Saudi Arabia, Colombia, and the People's Republic of Congo all had post‐pandemic growth rates of 6% or more. Perhaps, not too surprisingly, Iraq topped the growth chart with a growth rate of 9.3%. Ireland was close behind with a 9% increase; Australia and the United Kingdome are both still growing above 3%.17

The US economy was shrinking for the better part of the year—averaging out at 1.6% and is still facing the prospect of a full‐blown recession. With the exception of Japan, which is also struggling at 1.7%, my point is real GDP growth in these countries is two and three times ours in the United States. The Fed's attempt to grapple with inflation has additional headwinds.

Ultimately, growth trends lead to inflation. The best way to fight inflation is to let your domestic currency grow in value. And here is where large holdings of US debt become important. Because central banks around the world hold vast sums of US debt, they can also directly impact the value of the dollar.

We are now seeing a trend in Asia toward buying fewer US dollars and then selling the holdings they already have, as well as selling off US bonds. All of these changes will force the US dollar to fall and interest rates to rise here at home. In other words, Asian inflation is held in check and transferred into US inflation. This will ultimately be the price the United States will have to pay for allowing its federal and consumer debt to get out of control.

So domestic interest rates are not really controlled by the Fed any longer. The fact that Asian central banks own such vast dollar reserves and hold so much debt means they will determine not only how much inflation takes place, but also where it takes place.

The trend toward dumping dollars and debt will have a direct impact on the US stock market. Because the dollar has been falling in recent years, foreign investors in US stocks—representing more than 10% of the whole market—have been getting lower returns on their investments. When the dollar takes an even sharper turn south, those foreign investors will sell. That will mean that the supply of stocks will increase rapidly or, putting it another way, prices will plummet as foreign investors start dumping US shares.

WHEN JOBS WERE SENT OVERSEAS

The US government likes to minimize the trend in outsourcing of jobs. They point to job numbers—the creation of millions of new jobs, especially in election years. But the sobering truth is far different.

The US labor market has traditionally been defined by higher wages than in any other industrialized country. But the emergence of cheap production overseas means that companies are going to seek the most competitive labor source. Therefore, high‐paying jobs in the United States are disappearing, and rapidly. The average American factory worker gets $17.42 per hour, which works out to be around $36,230 a year.18 In China, while wage rates vary by region, the average salary is still just $3.80, roughly $8,248 a year. You can see the difference. With US workers earning more in four months than Chinese laborers get in one year, our labor economy still cannot compete. The Chinese economy—with millions of people looking for work—can afford to compete with US wage levels by offering dirt‐cheap pay, and there is an infinite supply glad for the work—even despite Chinese government complaints that wage rates are rising too quickly. The pandemic lockdowns have only made this situation more complicated.

As a consequence of globalization, wages in the United States are flat. In fact, for the first time in decades, wages actually fell in the United States in 2022, by more than 1%.19 Of course, some isolated and highly specialized industries will continue to hold the edge in America, but on average, high‐paying wages are being replaced overseas and our so‐called job growth is in the lowest‐paying industries. We see evidence everywhere. Almost no denim jeans are made in the United States anymore. Most of our clothing (95% of all footwear, for example) is imported from China and other Asian countries. More than half of all laptop computers are manufactured in Asia, and less than a decade ago virtually all of these were made in the United States.

What has brought about this huge change? We have to realize that the change is significant and has ramifications as great as any economic revolution. We must confront the fact that

as a result of the breakdown of communist and socialist ideology and the end of isolationist policies on the Indian subcontinent—the world's economic sphere was enormously enlarged with close to three billion people joining our free‐market, capitalistic system. The importance of adopting capitalism in countries like China, the former Soviet Union, Vietnam, and India cannot be underestimated and will again radically change global economic geography.20

Little discussion has been given on the impact of these three billion new capitalist competitors with the United States. It is, indeed, hard to fathom the overall impact of such a large shift in economic influence, but the shift is very real. The fact that US jobs are being transferred to countries that were previously in the Communist bloc makes the point: As long as these countries were our enemies, there was no trade between us. Now that we are all trading partners, all of those people are a cheap labor pool.

The problem goes back to the Fed and its ill‐advised monetary policies. Driving down interest rates has, more than anything else, caused the shift in jobs. We want to buy from foreign countries, and we're content to do so with debt, especially as long as interest rates are low. Unfortunately, this has created real inflation throughout our economy, at least on the cost side. But on the wage side, we've seen no growth at all. And eventually, this disparity is going to backfire on the Fed and on the American consumer.

HIDDEN INFLATION IGNORES THE REALITY

With wages flat and prices starting to rise, something has to give. It's going to come to a head. Gas prices are increasing rapidly, cutting into the discretionary income of most American consumers. Think about where this is going to hurt the most. Three areas deserve special mention: gas prices, mortgages, and credit card debt.

- Gas prices. That fill‐up costing $17 or $18 only a few years ago has risen to $30 or $40 per tankful, and likely will go far higher before it settles down—above $100 a tank if you drive a monster SUV with a 30‐gallon tank. That's a real bite out of anyone's budget. At the same time, with wages remaining flat and the dollar's buying power falling, the increased cost is even greater than the dollar‐to‐dollar comparison.

- Adjustable‐rate mortgages. More and more refinanced mortgages and first‐time mortgages have been underwritten with dirt‐cheap adjustable‐rate mortgages. Even with annual caps on increases and life caps on the loans, many homeowners will not be able to keep up with their mortgage payments as higher rates begin to kick in. Remember, wages are flat, but interest expenses are going to rise. So as previous factory workers' hourly wages fall from $17 down to $10, mortgage lenders will be sending out letters telling them their monthly payments are going up.

- Credit card debt. As people move debt around from one card to another with overall balances growing month after month, it is possible to take advantage of low rates and special offers. These three‐month no‐interest or low‐interest deals were great in the past because they allowed consumers to use so‐called free money, at least for a few months. But what happens when those special deals start to disappear? Rates will rise, minimum payment levels will follow, and the free money will dry up. Credit card consumers will need to stop buying and to begin repaying their debt—at higher interest rates and using dollars of lower value.

It was only during the Powell Fed that the media gave up parroting the idea that while the dollar is falling against other currencies, we have little or no inflation. Yet a devalued dollar is precisely the definition of inflation in one sense. But inflation can be defined in another way too: Dollar values remain steady, but prices rise. In reality, these are just different aspects of the same phenomenon: a reduction in purchasing power.

Every investor will naturally want to look for ways to protect assets in the coming changes we are going to see. But those who understand the problem will also recognize that there is a solution. It is going to be found in the recognition of a single reality:

As the value of the dollar begins to fall, a corresponding and offsetting rise in value of commodities, raw materials, and tangible goods will occur.

In the large view, this means that investors will do best in the coming fall of the dollar by looking for investments that will benefit from that trend. For those who want to remain in the mutual fund sector, several funds emphasize profits resulting when the dollar falls and commodities (such as gold) rise in value. In the next section, you will see how open‐end funds, closed‐end funds, and exchange‐traded funds (ETFs) can be used defensively to create profits when the dollar falls. The fund approach can work equally well to take advantage of rising prices in oil and other commodities.

For the sophisticated investor willing to take greater risks, currency speculation and using options or financial futures can be highly profitable. But these specialized derivatives markets demand great skill and experience, not to mention superb timing.

THE ESSENTIAL INVESTOR

The US economy is vulnerable on so many fronts. Social emphasis is being placed on protecting ourselves against terrorists and the threats of nuclear and chemical attack. But perhaps an equally serious peril is being ignored: our dependence on Middle East oil, for example.

We face a shrinking dollar, growing federal debt, increasing trade gap, record‐high consumer debt, mortgage bubble, rising oil prices, inflation, flat productivity, falling wages—all part of the same trend translating to financial vulnerability, of course. But this economic sword of Damocles21 points the way to how everyone can change their investing mode, not only to avoid loss but to maximize their investment profits.

If you accept the suggestion that big changes are going to be coming in these arenas, how can you reposition assets without also increasing market risks? Most investors are not going to sell their equity positions and go short on stocks, sell options, or sell futures. It simply isn't within their profile to do so. The trick is to find ways to take advantage of the coming changes in smart ways, and there are several. The way you choose to change strategies should depend on your investing experience and knowledge, risk tolerance, and personal preferences. In seeking ways to reposition your portfolio, keep in mind three major markets as places where you will want to either seek long positions: oil and natural gas, foreign investments, and gold. We still regard cryptocurrencies, options, green, and bio tech plays as speculative, unless you really know what you're doing.

Oil

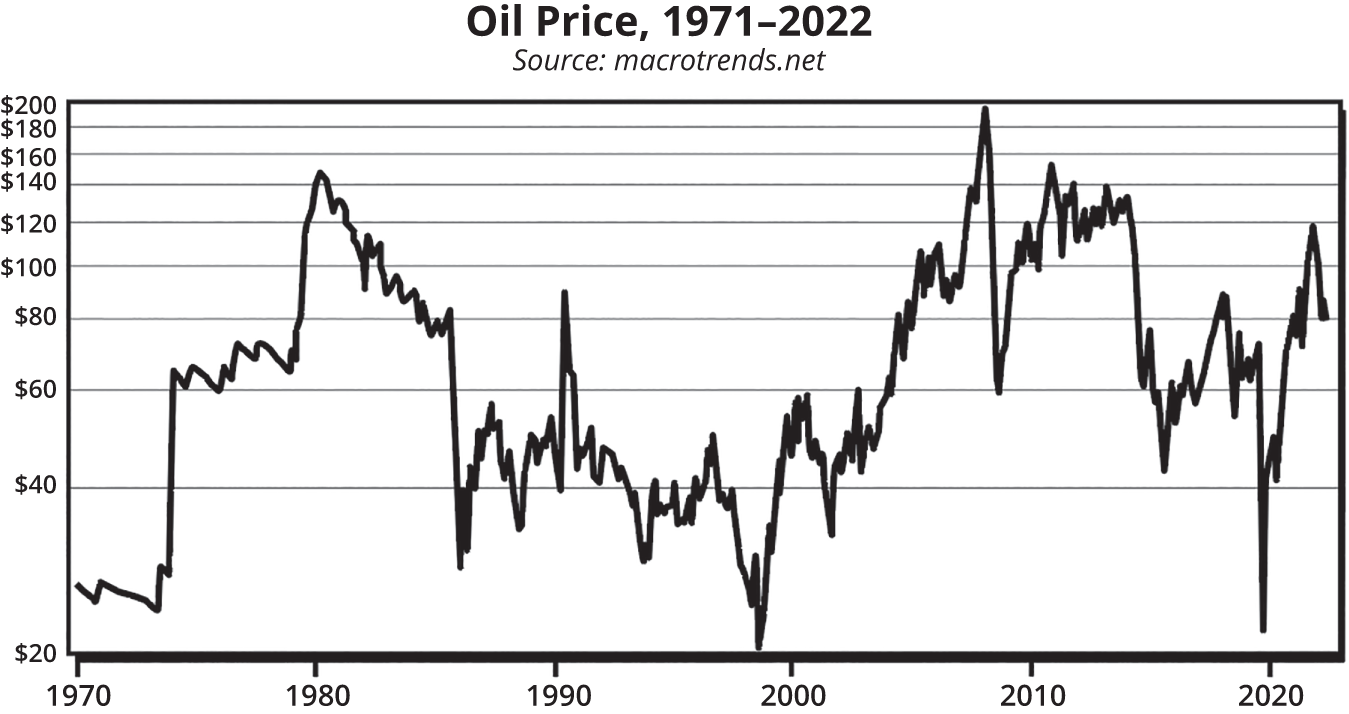

Consistent with the inflationary period from 1971 to 1980, oil went from a low of $23.91 in 1973 to a high of $144.73 in 1980—a 526% increase in just seven years. One hundred and forty‐four dollars in 1980 would be the equivalent of oil costing $518 today. After 1980, just like the gold price, gold took a two decade tumble down to a 1998 low of $20.31. And like the gold price, oil also bounced off the multi‐decade low, climbing for the next 10 years to a fresh high of $189.84 in the height of the Panic of ′08.

As you can see in Figure 8.3, after the high in May 2008, the price took a nosedive down $58.60 by December of the same year. These are the kind of rapid moves both up and that make investing in antacids a viable consideration. For the next decade, while the Fed was keeping rates close to zero, oil traded in a range both above and below $60. It wasn't until the deep shock of March 2020 that oil dropped to $21.82, only to spike back up.

FIGURE 8.3 History of Oil Prices, 1971–2022

Source: macrotrends

A year later, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, subsequent economic sanctions, and supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic saw oil above $100 again. It hit $116.39 in May 2022. Like gold, oil is priced in dollars, so the sustained trend in oil is determined as much by dollar weakness as in short‐term supply concerns. Russia has been trying to form alliances outside the dollar‐dependent West, pricing its oil in rubles and seeking stronger relationships with India and China.22

Prior to the lockdowns, the oil price was also increasingly influenced by growing demand for oil from China. Our long‐time allies in the oil markets have begun treaties selling oil directly to the Chinese priced in Yuan. Its oil imports were up nearly 40% in the early part of the twenty‐first century. Since oil trades in a global market growing demand also driving up prices paid in the United States. Pre‐pandemic, Chinese industry demand for oil was experiencing the highest growth curve in the world. We expect once the virus is dealt with to the Chinese government's satisfaction, consumption growth will return.

On its recent historical trend, COVID‐19 notwithstanding, oil consumption in China, projected forward only a few years, has the capacity to outpace any hopes of production keeping up. We can safely assume based on the trend in both industrial and consumer use that China is going to be the major oil consumer in coming years. So there is no logical reason to expect oil prices to drop. Rising oil prices affect one‐third of all US companies in some way. They create a double whammy on corporate profits. First, they drive up operating costs, and second, higher prices lead to reduced consumer spending. So it isn't just oil; it's the whole economy and any industry using petrochemicals, which includes construction, manufacturing, clothing, carpeting, and a vast number of other industries.

Increased demand affects oil prices as much as weather patterns, political problems, and of course the threat of terrorism. And there is little the United States can do to fix the problem. The relationship between oil discovery and production also looks quite dismal. With the current push toward green energy and a difficult regulatory environment in the United States for new drilling, transportation, or pipeline development, the headwinds are getting stronger.

What can investors do to position their portfolios? Stocks in companies involved in oil drilling and exploration, as well as those supplying drilling ventures, will continue to be solid investment opportunities in the future. New demand for oil rigs and drilling will push profits and stock prices higher. With OPEC already producing at 95% capacity, it is hollow to blame OPEC's policies for shortages. The truth is, reserves are dwindling as demand grows. Evaluate the oil production and drilling industry. Look for stocks that will benefit as oil prices rise. For mutual fund investors, seek out energy and commodity funds. For the more advanced investor who is comfortable with options, consider buying long‐term calls in oil‐related sectors with the greatest growth potential. Consider the four major subsectors within the larger energy sector of the market: coal, oil and gas (integrated), oil and gas operations, and oil well services and equipment.

Of course, looking for energy‐related mutual funds and ETFs is also a wise move. With prices rising, oil and gas companies and their products will become more in demand in the future.

Foreign Investments

Why invest overseas? Let's recall that China holds a huge amount of US Treasury debt—not because it wants to per se but because holding US debt gives China economic leverage over the United States in several ways. First, it ensures the continued trade gap favoring China and hurting the US economy. Second, holding this debt enables China to virtually control US buying patterns, interest rates, and economic policy. Third, China's currency is largely pegged to the US dollar. If the dollar falls, so goes the yuan.

The more we buy from China, the more US debt China acquires. This helps its producing economy while further damaging our consumer economy. What happens next? In the summer of 2007, China began selling off US debt. This caused US interest rates to rise as the Treasury was forced to find new lenders. For those investors anticipating this change, several smart moves are available. Three potential strategies offset the consequences of US–China trade.

First, invest outside of the United States, either directly buying stocks or through ETFs. Seek investments in countries producing commodities and providing valuable resources, such as Australia. This continent is resource rich and geographically positioned to become a major supplier to China. Investing in Australia is a smart way to profit from China's growth without having to invest money in China itself.

Second, buy commodities by purchasing shares in corporations, index funds, or mutual funds specializing in the energy and commodities sector (oil and gas, precious metals, steelmaking). Third, use options to control large numbers of shares rather than buying shares directly.

The ultimate dollar hedge investment will always be gold. Investing in gold through ownership of the metal itself, mutual funds, or gold mining stock provides the most direct counter to the dollar. As the dollar falls, gold will inevitably rise.

In a moment, we'll provide you with many ways for positioning your portfolio to profit from a bull market in gold. For now, we emphasize the high probability of gold's future. The real potential for profits in the coming years and decades is not going to be found in the traditional American blue‐chip industry. That is a financial dinosaur that can no longer compete in the world market. The future growth is going to be seen in gold. The world economy may remain off the gold standard, but ultimately the tangible value of gold as the basis for real value—whether acknowledged by central banks or not—will never change. Historically, this has always been the case, and it always will be. In other words, we are on a “gold standard” in spite of the popularity of fiat monetary systems.

Besides knowing where to position your capital to maximize returns when the dollar falls, also think about strategies that sell the dollar to produce profits.

How to Sell the Dollar

In 2004, then‐Treasury Secretary John Snow was traipsing about the globe trying to “talk the dollar down.” Why? In a word: debt. At the first writing of Demise of the Dollar, our debt stood at $7 trillion, with interest payments in fiscal 2003 totaling $318 billion. Now, the national debt is $31 trillion with paid interest of $3.6 trillion.23,24

The Fed and Treasury have engineered a strategy to pay off the debt with weaker and weaker dollars. And guess what? So far, so good. Of course, this is not the first time we've gone through a managed devaluation of the currency. In the 34‐year period since Nixon slammed the gold window shut and subsequently ended the Bretton Woods exchange rate mechanism, we've had only six major currency trends:

- Weak dollar 1972–1978 (7 years)

- Strong dollar 1979–1985 (7 years)

- Weak dollar 1986–1995 (10 years)

- Strong dollar 1996–2001 (6 years)

- Weak dollar 2002– 2008 (6 years)

- Strong dollar 2011–2022 (11 years)

Until this latest run between 2011–2022, the most notable period spanned the 10 years from 1986 through 1995. After a historic run of growing strength against other foreign currencies, it's a good bet the dollar will have an extended weakening period of six or seven years. There are ways to play these big trends in the market—direct and indirect speculations, using short‐ and long‐term options for each. These plays will help you safely position your money outside the dollar bear market. And you stand to make a fair amount of money, too.

But, as always, there is danger ahead. Once, we noted early in the last downtrend, the trade deficit passed the $759 billion mark—6.3% of GDP—foreigners had to shell out about $1.5 billion a day just to keep the dollar afloat. And even during the managed dollar decline of 2003, the trade imbalance continued to grow. In 2005, Stephen Roach, Morgan Stanley's chief global strategist, predicted that the current account deficit at the time was on course to reach $710 billion—6.5% of GDP. He was short by only a few billion.

Herein lies the drama. The Bank of Japan spent the equivalent of $187 billion in 2003—and $67 billion in January 2004 alone—in a bid to prevent its strengthening currency from choking off the country's export‐led recovery. In dollar terms, the Bank of Japan is now spending more than $1.5 billion every day trying to keep the yen from strengthening against the greenback.

Over a four‐week period in the fall of 2003, combined foreign central bank purchases of US securities topped $40 billion, more than $2 billion every trading day. Yet these central bank billions managed merely to limit the greenback's decline to just 2.3% over the same period. Can you imagine what would have happened if the banks hadn't pumped that money into the Fed's reserves? One former currency trader has asked, “If $40 billion cannot bring about even a minor rally, just how weak and despised is the once‐almighty dollar?”25

We have had to rely on the kindness of strangers to keep the dollar afloat at all. And perhaps for far too long. “We're like the untrustworthy brother‐in‐law who keeps borrowing money, promising to pay it back, but can never seem to get out of debt,” Jim Rogers writes. “Eventually, people cut that guy off.”26

There is no way the United States can possibly pay off its creditors should they decide to cash in their IOUs. Right now, the United States holds only about $70 billion in reserves against its obligations—much less than 2005's $87 billion. That would last about three minutes should creditors begin to sell the dollar rather than trying to support it.

It's hard to imagine, isn't it? The world's reserve currency spiraling downward, out of control. But then, that's what the British must have thought in 1992 when they attempted to manage a devaluation of the pound. Despite the Bank of England's best efforts, sterling got away from them; the currency collapsed and Britain was kicked out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) established to pave the way for the euro. On that day, known as Black Wednesday in Britain, currency speculator George Soros is rumored to have made as much as $2 billion. Don't be surprised if more fortunes emerge in the future as the dollar slips dangerously close to free fall.

By flooding the system with liquidity, the Fed cannot control the value of the US dollar against foreign currencies nor can the Fed control the dollar's purchasing power—at least not indefinitely. The Fed's current policies can “give the majority of investors the illusion of wealth as asset markets appreciate,” wrote Marc Faber in November 2003,27 “while the loss of the currency's purchasing power is hardly noticed. This is particularly true of a society that has a very large domestic market, where 90% of the people don't have a passport and therefore know little about what is going on outside their own continent. And where the import prices of manufactured goods are in continuous decline because of the entry of China, as a huge new supplier of products with an extremely low cost structure, into the global market economy.” If that's the case, you should look at any declines in the dollar as an opportunity to make some money.

The dollar is the single biggest element of risk in the world of finance today. Rearrange the current system of world finance ever so slightly, let confidence in the greenback falter, and the mighty dollar could go up in flames. There are many ways to hedge against this risk. Better still, there are many ways to profit from the likelihood the dollar will fall. Some methods are direct, some indirect. Some are leveraged, some unleveraged. There is a methodology for every taste, but before explaining the specifics, we ask: What ails the dollar?

The dollar is a victim of its own success. It is America's most successful export ever—more successful than chewing gum, Levi's, Coca‐Cola, or even Elvis Presley, Britney Spears, and Madonna put together. Trillions of dollars flow through the global financial markets every week, and they are readily accepted at large and small—and clandestine—business establishments from Kiev to Karachi.

Today, there are simply too many dollars in circulation for the currency's own good. Why? Americans have been living beyond their means for more than two decades. The US dollar's problems stem from a single cause. “If there's a bubble,” wrote David Rosenberg, chief economist at Merrill Lynch, “it's in this four‐letter word: debt. The US economy is just awash in it.”28

You've seen it firsthand: John Q. Public now holds more credit cards and outstanding loans—with a higher and higher total debt load—than ever before. Outstanding consumer credit, including mortgage and other debt, reached $9.3 trillion in April 2003—a significant increase from its $7 trillion total in January 2000—but by the third quarter of 2007, debt had nearly doubled since 2000, to $13.7 trillion. With consumer spending alone responsible for approximately 70% of US GDP, that's quite a hefty personal debt load.

The corporate debt picture is no better. American companies have never depended so much on sales of their corporate bonds. Between 2002 and 2007, investment‐grade corporate bond sales increased nearly 60%, growing from $598 billion to $951 billion. But junk bond sales for that same period broke the bank, surging from $57 billion to $133 billion.

The third leg of the debt problem, following consumer and business debt, is Uncle Sam. Government debt as of November 7, 2007, officially passed $9,000,000,000,000. That's about $30,000 for every man, woman, and child in the country. This total includes debt owned by many types of investors, from individuals to corporations to Federal Reserve banks and especially to foreign interests. (By 2004, foreign central banks had stockpiled more than $1.3 trillion worth of dollar‐denominated Treasury bonds and agency bonds at the Federal Reserve. By 2007, foreign debt had nearly doubled, to $2.033 trillion.) What the $7.8 trillion figure does not account for are items like the gap between the government's Social Security and Medicare commitments and the money put aside to pay for them. If these items are factored in, the government debt burden for every American rises to well over $175,000.

If we're nearing the end of an 11‐year stretch of a strengthening dollar, what should you do? On way to answer that question is look at what great investors have done.

In 2005, the Methuselah of investment mavens, Sir John Templeton, then 93, said you should get out of US stocks, the US dollar, and excess residential real estate. Templeton believed the dollar would fall 40% against other major currencies, and that this would lead the nation's major creditors—notably Japan and China—to dump their US bonds, which would cause interest rates to run up, thus beginning a long period of stagflation. He was right.

Don't let his age fool you—Templeton was still sharp in 1999 when the financial industry hacks in Florida were urging their customers to buy more tech stocks. Templeton warned that the bubble would soon burst. He was right; they were wrong. Of course, he was only 87 back then. Templeton died in 2008 at the age of 96. He didn't live long enough to see what he was confident would be on the horizon. Were he alive today, he'd almost certainly be right again.

Other great investors were also getting out of the dollar. For the first time in his life, Warren Buffett was investing in foreign currencies. George Soros, who made a fortune selling sterling in the 1992 ERM crisis, warns that the US system could “blow up” at any time. Richard Russell, the influential editor of the Dow Theory letters, speaking at the New Orleans Investment Conference, warned: “If ever there was a crisis that could shake the global economy—this is it.”

When old‐timers nod their heads in agreement—especially when they happen to be the most successful investors in the world—their advice may be worth listening to. The trend they observed is likely coming around today, again.

American consumers, companies, the US government, and the country as a whole owe more dollars to more people than ever before. But perhaps the greatest threat to the US economy is its foreign creditors. There is a market‐based limit to the number of dollars foreigners are willing to buy and hold and thus a limit to their willingness to service our credit habit. Why? Because the United States, while still the world's number‐one economic power, is showing itself to be an erratic steward of its own currency.

You don't spend your way to prosperity; no nation ever has or ever will. But guess what? That very idea is the basis of US and Fed monetary policy. Never in US history have the imbalances in the economy been so pronounced, or so dangerous. “My experience as an emerging markets analyst in the 1990s taught me to be on the lookout for signs of financial vulnerability,” observed analyst Hernando Cortina in a Morgan Stanley research note in 2003. His words ring just as true today:

[The signs] include ballooning current‐account and fiscal deficits, overvalued currencies, dependence on foreign portfolio flows, optimistic stock market valuations coupled with murky earnings, questionable corporate governance, and acrimonious political landscapes. Any one of these signals in an emerging market usually raises a red flag, and a market that combines all of them is almost surely best avoided or at least underweighted. I didn't imagine back then that one day these indicators would all be flashing red for the world's biggest and most important market—the USA by‐the‐numbers analysis of America's macro accounts in a global context doesn't paint a flattering picture.29

Yet for growth‐starved financial markets, perceptions and hope are often more important than economic reality. According to the macro indicators that the IMF uses to assess emerging‐market economies, the United States fell between Turkey and Brazil. Hernando Cortina politely concluded: “Investors contemplating the purchase of US dollar‐denominated assets would be wise to factor in significant dollar depreciation over the next few years.”

“Households have been on a borrowing spree,” added Northern Trust economist Asha Bangalore also in 2003. As we've seen, that trend is as apparent and true today, if worse. Consumer credit is skyrocketing while the savings rate has plummeted. Bangalore:

This measure of household borrowing reflects mortgage borrowing, credit card borrowing, borrowing from banks, and the like. Household borrowing is not only at a record high but a new aspect has emerged—household borrowing advanced during the recession unlike in every other postwar recession when households reduced borrowing. The good news is that consumer demand continues to advance with the support from borrowing.30

The bad news is that no economy has ever borrowed its way to prosperity. Despite the conspiracy against it, the dollar has avoided a downright free fall. That's because dollar investors across the globe are still convinced that, given favorable credit conditions, the US economy will surely reenter the heyday of the late 1990s, taking dollar‐denominated assets to new heights. But someday soon, we think, investors will be disabused of their illusions. Sure, the stock market rallied briskly in the recent past, but the US economy continues to struggle. Unemployment persists. And the twin deficits loom larger and larger.

If and when America's creditors—domestic and foreign—decide the country's massive, record‐breaking level of debt is reason enough to get out of their dollar investments, the dollar will have nowhere to go but down, precipitously. We don't know when the exact moment of truth will arrive, but we know it cannot be far off.

Excessive debt is not the only ominous development in the US economy. Just as foreboding is the American consumers' persistent belief that they are wealthier than they actually are. US financial assets are, once again, in the grip of a large bubble, despite fears of a recession. The Fed's frantic attempt to fight inflation spooked stocks into bear market territory in 2022. But late in the year the market began a rally again in a way completely dissociated from any real measure of value.

In fact, the rally in stocks has been so strong that it has rekindled investors' belief in a new bull market, full economic recovery in the United States. But a funny thing has started to happen. The US stock market is soaring. Normally, that means the dollar would go with it; when a country's stock market goes up, demand for its financial assets usually goes up, too. But the dollar is beginning to get dragged down again by debt—government debt, personal debt, and corporate debt. Investors want a bull market, and so they're making one. But the dollar reflects the real state of the American economy … and it knows better.

Foreign investors are especially burned when stocks and the dollar part company. At first blush, the rallying US stock market seems like a very inviting place for their capital. All denominations are welcome, but not all guests are treated equally well.

Foreign bondholders are faring no better. US debt held by foreign countries is $7.07 trillion.31 So, roughly speaking, every 10% drop in the dollar's value impoverishes our foreign creditors by about $100 billion on their US Treasury holdings alone!

That's real money. But if you look closely at the timer clicking away on US Debt.org, the dollar amount of debt held by foreigners is dropping almost as rapidly as the rate of spending is going up!

How is it possible that stocks continue their winning ways, even while the dollar continues its losing ways? These two inimical trends are strange bedfellows indeed. What makes the pairing particularly bizarre is the fact that our nation relies so heavily upon the enthusiasm of foreign investors for US assets.

What is the Fed doing, and why? One writer has pegged the answer:

The Federal Reserve Board [manage] the inflation rate, while the US Treasury is trying to talk down the dollar exchange rate. Not every day does the world's hegemonic power pursue a policy of currency debasement. Still less frequently does it have the courtesy to tell its creditors what it's doing to them.32

Indeed. The Fed and Treasury are engaged in a kind of collusion to lower the dollar's value. And that's a very dangerous game to play, especially for a country like the United States, which relies so heavily upon foreign capital to finance its economy. It has become fashionable in the corridors of power in Washington to advocate “market‐based” exchange rates—code for “weak dollar.” A weak dollar, it is widely believed, will lead to a strong economy. Hmm.

In the olden days, of course, the Fed was supposed to pursue “monetary stability.” But in the enlightened twenty‐first century, the Fed has much grander designs. It imagines itself a kind of marionette master to the world's largest economy, making it dance whenever it wishes, simply by tugging on one little interest rate, or by tugging on the dollar. And so it tugs, and tugs, hoping to revive the economy.

The US Treasury Department is also conspiring with the Fed to weaken the dollar. Hasn't Treasury Secretary Snow touted the weak dollar as a surefire cure for the struggling US manufacturing sector? And hasn't the dollar been tumbling? And yet, isn't the manufacturing sector struggling just as much as it was when the price of a euro was only 83 cents, instead of $1.25?

It's obvious to almost every citizen who does not live in Washington, DC, that devaluing the dollar to stimulate economic growth is a fool's mission. At the turn of the century a little under three hundred dollar bills purchased an ounce of gold. Today, an ounce of gold costs 2,000 paper dollars. Our manufacturers will have become so competitive that they will be exporting firecrackers to the Chinese, or so the gang on Capitol Hill believes. But in fact, we will all be poorer for embracing the idiocy of “competitive devaluations.” The problem is, once a devaluation trend begins—we call it inflation—it is very difficult to stop.

A TREND WHOSE PREMISE IS FALSE

“Find the trend whose premise is false, and bet against.

—George Soros

So what do you do now? The solution comes from repositioning, and the best cues for when, how, and where are found in the gold market—which prospers during times of geopolitical uncertainty and traditionally rises in value when the dollar falls. As we've noted, over the past two decades the spot price of gold has risen from $235 in 1999 to a sustained level around $2,000 by the early 2020s. The metal's impressive rise inspired a dramatic rally in gold shares that has vaulted the XAU Index of gold stocks to a high of $226 in 2011. By 2022, it was making another run starting the year at $158.

What does the gold market know? That the Fed's reflation campaign will succeed too well? A little bit of inflation—like a little wildfire—is a difficult thing to contain. And the gold market seems to have caught a whiff of inflationary smoke.

Or does the gold market know that Iraq will continue to serve as a breeding ground for terrorists and a habitat for anti‐American terrorist acts? As the Iraq situation continues, the dollar will suffer … a lot.

Or maybe the gold market knows only that US financial assets are very expensive, and worries, therefore, that US stocks selling for 35 times earnings and US bonds yielding 4.5% are all too pricey for risk‐averse investors to own in large quantities. A vicious cycle is hard to stop. The dollar's descent is the most worrisome—and influential—trend in the financial markets today. And yet, as long as Cisco is “breaking out to the upside,” few investors seem to care about the dollar's slide into the dustbin of monetary history. The dollar's demise is not inevitable, just highly likely.

When a currency falls, in theory anyway, interest rates usually rise. A government whose currency is falling apart tries to make assets denominated in that currency more attractive by paying higher rates of interest to potential investors. And if the government doesn't raise rates, the market will do it by selling off bonds and driving yields up.

And so, in theory, you would normally expect to see a falling US dollar accompanied by rising US interest rates. The difficulty from the Bush/Greenspan/Bernanke perspective is that rising long‐term rates pose an enormous problem: They make it significantly more expensive for debtors—from US consumers to the US government—to service their obligations. And these costs are not negligible.

In fiscal year 2007, for example, the government was obliged to pay out a whopping $429 billion in interest expense on the public debt outstanding. At a 1% rise in interest rates, that would add $43 billion in interest expense. And to meet this added interest expense, the government would, of course, have to float even more bonds, and at the higher interest rate.

This scenario is the government's nightmare. When the falling dollar eventually pushes interest rates up, the Treasury will have to issue more debt at higher interest rates simply to pay off its existing debt. But if the Asian economic juggernaut were to discontinue recycling its excess dollars into US government bonds and Fannie Mae debt, the dollar would suffer mightily. How much longer until our luck runs out?

In some way, shape, or form foreigners lend our consumption‐crazed nation $1 trillion every year. We Americans, in turn, use the money they send our way to buy SUVs, plasma TVs, and costly military campaigns in distant lands. However, we do not forget to repay our creditors with ever‐cheaper dollars. Someday soon, foreigners must lose interest in subsidizing our consumption habit.

That the dollar's decline comes at the urging of the same nation that prints the things is an irony that is not lost on the world's largest dollar holders. Reading the tea leaves, many Asian central banks are still exploring ways to lighten up on their US dollar holdings. “The Chinese aren't lapping up our Treasury paper for its great investment attributes,” writes Stephanie Pomboy of MacroMavens, “but [rather] because of a mechanical need to maintain the yuan/dollar peg.”33