Chapter 20

Demystifying Commercial Research Methods

CONTRIBUTOR PROFILE: ANNE DYE

Anne Dye is Head of Technical Research at the RIBA, responsible for delivering the research agenda in alliance with the RIBA Research and Innovation Group. This includes the development, support and promotion of a range of strategic built-environment research projects within the RIBA, in partnership with other organisations and within the wider research community, as well as providing advocacy for research to key stakeholders.

Context

‘People often reject creative ideas even when espousing creativity as a desired goal.’1 Why should this be, and what are the implications for architects – particularly architects in commercial practice?

Research published by Cornell University’s ILR (Industrial and Labor Relations) School suggests that when people wish to reduce uncertainty (and so risk), an unconscious bias against creativity is activated.2 And, as a recent series of roundtable discussions at the RIBA highlighted,3 risk is a significant concern for commercial clients. This is one of the reasons why, for architects in commercial practice, skills related to addressing certainty and risk (such as those below) are advantageous.

Skillset of commercial architects 4

- Appraisal of financial viability – translation of construction knowledge into the language of business.

- Ability to maximise investment potential – the planning, design and implementation of a development, redevelopment or regeneration project with multiple uses of a single prime use, the success of which is predicated on financial viability.

- Efficient business practice – leadership and planning to reduce risk to the client.

- Conversant with patterns of consumption – understanding and application of knowledge about retail, marketing, real estate and related fields.

- Regulatory and planning compliance – maintaining standards while maximising value.

These skills go hand in hand with a number of types of research that also support commercial architectural practice. What is particularly important in research in commercial practice is that it leads to actionable insights. This means that exploratory research is likely to play a lesser role in a commercial practice’s projects (though it might form part of the a practice’s own research) and that other methodologies – especially those that are well known and command the client’s confidence, including those from other fields such as statistics, the physical sciences, or historical and legal disciplines (as Gordon Gibb uses in his work – will dominate.

But research can also help to lessen the impact of the risk-averse nature of very commercial clients on practice, helping clients to understand and value the creative skills of architects – or by acting to change the environment in which architects practice, for example by influencing the policy around procurement, which Walter Menteth has been working towards. This chapter explores some of these methods, and their relevance to commercial practice.

Using Research to Inform Projects

Where there is a need to carry out research to support a commercial project it is likely that there will be a very specific use intended for the results and insights from the project which will lead to focused research questions. The research questions will help you focus the review and minimise the time and resources needed to collect relevant and useful evidence.

You and your clients will also want to make sure that you can have a high degree of confidence in the results of the research. This doesn’t necessarily mean favouring quantitative data over qualitative, but it does require care and attention to detail throughout the research process.

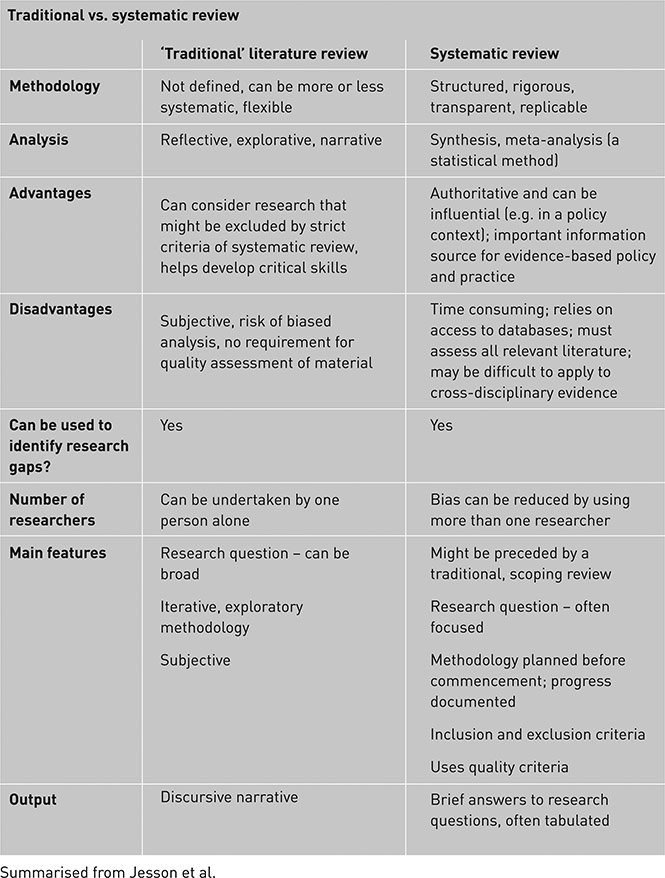

Before undertaking research for a project it is also important to have a good grasp of the current knowledge on the subject. Staff may have collected literature related to the subject, and this can be a good starting point for a review. You need to decide whether a traditional literature review or a systematic review will meet your project’s needs better – see box, below. A full systematic review may not be called for, or affordable, but you may want to incorporate some of the aspects of it into your literature review, such as using rigorous inclusion and exclusion criteria for evidence, or using more than one reviewer to reduce bias, this can make a traditional literature review more authoritative. Alternatively you might consider a ‘rapid appraisal’5 which has some characteristics of a systematic review but is less time-consuming to produce.

Doing (or reviewing) systematic reviews and rapid appraisals might be particularly useful for healthcare buildings where evidence-based design is well embedded. But all types of project and client can benefit from insights derived from previous research and projects.

Existing buildings are often useful when talking with a client as examples of what can and cannot be achieved in a new project. While this might be done informally through a guided visit to a practice’s building, it is worth remembering that case study analysis is also a formal research strategy, which can use qualitative or quantitative methods. Case study research is especially suited to complex situations and multidisciplinary phenomena – such as buildings and their interactions with their users and context – with multiple sources of evidence. One source of evidence that may be useful in case studies is post-occupancy evaluation (POE), and its big sister building performance evaluation (BPE).7

By formalising your case study processes your insights will be more authoritative and more likely to persuade a sceptical client. You may also want to consider multiple case study analysis, where you can explore concepts and ideas in greater detail, either to inform a particular project or the practice’s work in general. Robert Yin’s book Case Study Research: Design and Methods is possibly the most useful resource for those starting to do formal case study research.8

Research is not just something external that informs briefing and design, but can be an integral part of these processes. Often, a piece of research will have an experiment (testing the impact of one or more specific variables on outcome of interest)9 at their heart – a powerful methodology, as it has the potential to establish causal links.

Modelling – experiment’s powerful ally (with an Achilles heel)

It is not always possible to do physical experiments for either practical or ethical reasons. For example, you probably wouldn’t want to set fire to a completed building to assess spread of fire and effectiveness of evacuation.

Modelling or simulation, can help overcome these issues. A model can be either physical, for example using salt baths to model heat flow and natural ventilation10, or virtual, which is becoming progressively more sophisticated as computing power continues to increase. Software can model physical properties – such as daylight, energy consumption or thermal response – or behaviour, such as crowd movement through stadia. Alternatively it can provide a different way for people to interact with a proposed design, such as through the use of virtual reality headsets, and provide evaluation feedback. These can help architects to make informed design decisions, evaluating the pros and cons of different options.

But simulation does not always predict the actual behaviour of the completed building. Why? Are the maths or physics wrong? Are the assumptions about things like human behaviour too generalised? It turns out to be a mixture of reasons but in particular the difference between as-designed and as-built – even where issues are ‘small’, such as mortar bridging a cavity wall or half a brick in a ventilation duct11 – can have big impacts on performance and it is rare that the building is actually used as the client predicted. This can lead to large discrepancies between modelled and actual performance – the so-called performance gap.

This type of research can, for example, help a building meet sustainability aspirations under challenging circumstances such as in the heat of Abu Dhabi. For the Al Bahr Towers, modelling (physical and virtual) helped refine the design and performance of a contemporary and adaptive interpretation of a traditional mashrabiya shading screen which reduces solar gain by up to 50 per cent.12

Another experiment might be about how to improve the pedestrian flow through, and experience of, a railway station – as for the refurbishment of Kings Cross station in London. Arup, working with the architects Stanton Williams, used the pedestrian modelling methods Legion,13 STEPS14 and Pedroute when evaluating pedestrian flow through the station.15 In particular the Legion model allowed the team to look at the impact of types of pedestrian (commuters, those with reduced mobility, those with luggage), train timetables and issues such as those whose tickets are rejected by the ticket barrier and need to seek assistance.16 Arup disseminates its research outcomes and profits from sales of its journal. Others have dedicated research journals17 which help to promote their practice through research.

Using Research to Inform Practice, Build Reputation and a Practice USP

While much research in commercial practice is likely to be related to specific projects, other more speculative research projects can yield significant and long-lived advantages to a practice – advantages that far outweigh the resource implications. These projects might be exploratory; at the outset you may not be sure what type of insights you might find or even whether they will be useful or not, perhaps using methods such as Grounded Theory (see box, below). Alternatively they might answer specific questions that could be useful in informing the practice’s work, perhaps by doing statistical analysis of records from a database of the practice’s POEs.

Exploratory research; developing theory

An explanatory study might use quantitative methods (such as statistics or graphical analysis) or you might want to analyse information from your practice qualitatively, either to see whether an existing research question is worth pursuing (testing a theory) or to develop an entirely new theoretical understanding of your practice, project or clients.

One way to do this is to use a method such as Grounded Theory, where a theory is developed by looking for connections in raw data (for example from your own site notes, design team meeting minutes, focus group audio recordings, or even quantitative data such as that from POE) in a systematic way,18 similar to the way research is analysed in a literature review. The process of analysis is called coding, and can be done by hand, or by using software packages such as the free AQUAD 7,19 CAT (Coding Analysis Toolkit)20 or CATMA (Computer Aided Textual Markup & Analysis).21 A quick web search will yield the most up-to-date free tools, or you might consider a commercial package such as NVivo22 – especially if you intend to do many studies.

By using codified procedures such as Grounded Theory analysis to evaluate qualitative data you reduce the risk of bias, and are more likely to develop truthful (and useful) theory.

A good example of an exploratory study would be the collaborative study of the impact of flat-panel displays on trading room design23 undertaken by Pringle Brandon.24 The study both addressed prior client criticisms of the practice’s approach and directly led to work that made the practice ‘world-wide market leaders overnight’.25 It has also had a lasting impact on both the practice (it is still an important part of the practice’s marketing, reflecting the impact it has had on the practice’s profile and reputation among clients)26 and the profession, having been included in the Metric Handbook.27

Statistical methods

Statistical studies can be very powerfully persuasive in influencing clients and policymakers, but must be applied with care. Correlation does not always imply causation and, while studies with small samples open up new avenues of enquiry, be careful if using them to give ‘an indication’ of what the answer might be.

Using generalised research methods can lead practices on to develop their own research tools or to market specialised research services to their clients.

| Some commercial research services offered by architecture practices | ||

| Tool/Service (practice) | What it is | Research methodology (more information) |

|

|

||

| WorkWare, WorkWareLEARN and WorkWareCONNECT (Alexi Marmot Associates) | A suite of five methods looking at how buildings are used | POE - statistical and case study, quantitative and qualitative (aleximarmot.com/workware) |

| BUS (building use studies) methodology (Arup) | Domestic and non-domestic POE, used on the PROBE studies in the 1990s | POE-statistical and I case study, quantitative and qualitative (www.busmethodology.org) |

| Rapiere (Architype, BDSP, Greenspace Live and Sweett Group) | BIM-compatible carbon, energy and cost-modelling tool | Modelling/Simulation (rapiere.net) |

| Conservation reports | PPS5 statements, Heritage Impact Assessments, conservation management plans, views analyses, Conservation Area studies | Historical - architectural history graphical (alanbaxter.co.uk) |

Selling Research Services

Developing research in a practice that is not linked to particular projects, and so is likely not to have restrictions on how widely it can be disseminated, allows a practice to really develop its research skills and related tools. These can then be commercialised, bringing further financial benefits and cementing the practice’s position as a market leader.

Having a research speciality also allows a practice to offer one-off research services, which all add to the practice’s knowledge base and standing. Projects of this type include:

- Bringing together complex issues into guidance in Building for Life28

- Mapping and applying existing housing standards29, 30

These examples of research – across projects, practice and services – are just a sample of the myriad that can thrive in commercial practice. For those yet to develop research in their practice they can offer inspiration about how to get started, while for those looking to expand their research, this material flags a few additional avenues worth exploring.