12. Designing Evaluation

(IN WHICH WE LEARN THAT A, B, C, AND D ARE NOT YOUR ONLY OPTIONS)

The Challenge Of Doing Good Evaluation

What Does Learning Evaluation Look Like?

If you close your eyes and picture learning assessment, there’s a decent chance you’ll picture something like this:

The most common form of formal assessment is everybody’s favorite: the multiple-choice question. We’ve all answered more multiple-choice questions than we can possibly remember.

If we use so many of them, they must be the good way to do learning assessment, right? Well, they have a few main advantages:

• They are efficient to write, administer, and score.

• Grading is objective.

• They are consistent; everyone who takes the test can have the same experience.

OK, so what isn’t on that list? Oh yeah—there’s pretty much nothing on there about the learning advantages for the person taking the test.

Multiple-choice tests aren’t really about making the learner better at what they need to do. They are about making test administration efficient and consistent. If your main goal is testing and assessment, then that’s fine. You’ve got yourself a model.

But here’s the thing. Mainly what you learn from multiple-choice tests is how good the learner is at...taking multiple-choice tests. You don’t want to hand someone the keys to the helicopter just because they passed the 100-question multiple-choice test on the history of helicopter flight.

What are We Trying To Measure?

To do evaluation well, you should start by defining what you are trying to evaluate. Some of the things you might want to know include:

• Does my learning design function well?

• Are the learners actually learning the right things?

• Can the learners actually do the right things?

• Are the learners actually doing the right things when they go back to the real world?

Let’s take a look at each of these questions and the kinds of evaluation you can use to answer them.

Does It Work?

When you begin evaluation, the first question you want to answer is, “Does my learning design function well?”—basically, does the darn thing work?

This leads to all sorts of follow-up questions:

• Do I have enough content? Too much content?

• Are the instructions clear? Do people know what to do?

• Does the timing work, or does it go on way too long?

• Are learners engaged, or are they so bored they’d rather chew off a limb than listen any further?

• Are learners keeping up with the pace, or are they getting frustrated and left behind?

The best way you answer these questions = Watch actual learners use your design.

This could mean watching how learners react in a class, or how they use an elearning course, or what they do with other types of learning materials. We discussed this briefly in Chapter 2, but testing things out with actual users is really the only way to know what works and what doesn’t.

Both experience and good design make it easier to create a learning experience that works pretty well out of the box, but even the best learning experience has some hiccups the first time it’s executed:

This kind of thing is going to happen, so it’s probably better if it happens with a nice, tolerant pilot group who know that you’re launching something for the first time. This is something we do automatically with instructor-led classes. I often ask groups of training facilitators if any of them have ever failed to make adjustments between the first and second time they taught a class. No one has ever raised their hand. Of course you would make adjustments after the first time you teach something, so you should plan for a pilot as part of your design process.

Testing Digital Resources

Other types of learning materials—self-study materials or elearning or digital support resources—often get released without any kind of user review. Usually they are just reviewed by stakeholders or subject matter experts, which is a necessary part of the process, but getting feedback only from people who already know the topic well is a problem.

When you design a learning experience, it’s easy to get tunnel vision. You’ve been working for weeks or months, parsing out all the messy pieces of content and figuring out how to organize them, and finally it’s all making sense to you:

But your learners will be starting from scratch, and things that are now perfectly apparent to you will be a muddled mass of confusion to them. But you (and all the other experts and stakeholders) have lost the ability to see the confusion, because you’ve been so close to the material for so long. You need fresh, outside eyes from your target audience to really know what works and what doesn’t work.

The good news is that it has gotten very easy to test online digital resources. The steps are as follows:

1. Recruit some learners. You don’t need very many. The industry rule of thumb is that five or six end users are plenty. I’ve done user testing with two or three people and still gotten value from it. There are agencies that will help you recruit users, but when I needed middle-school teachers, for example, I asked friends and family to get volunteers.

2. Arrange a web meeting with a learner. You want to interact with each learner individually so that you can pay close attention to how they interact with your materials.

3. Explain the process. When they are logged in to the web meeting, explain that you are testing the digital resource (not them) and that they can’t do anything wrong. Ask them to talk aloud as they move through the elearning course or the digital resource.

4. Ask them to share their screen. Have them share their screen via the web meeting application, and have them access the elearning course or resource. Ask them to go through it or to perform specific tasks.

5. Watch what they do. If you have permission, record the session and watch what they do. See where they get frustrated or stuck, and see where they miss things. Don’t help them unless they are really stuck (you won’t be there for all the rest of your learners to explain things).

That’s it. Repeat the process with three to five other learners, and you will learn an enormous amount about how learning functions. Make changes and repeat the testing process as often as you can manage. You can also do these same steps in person if that is more convenient.

Steve Krug’s excellent (and entertaining) books Don’t Make Me Think and Rocket Surgery Made Easy are essential reading if you are designing and testing any kind of digital resource. Usability.gov is another great (and free!) resource for user testing materials and guidelines.

Using Surveys

“This whole user testing thing sounds complicated. Can’t we just give them a survey after they take the course to find out if it works?”

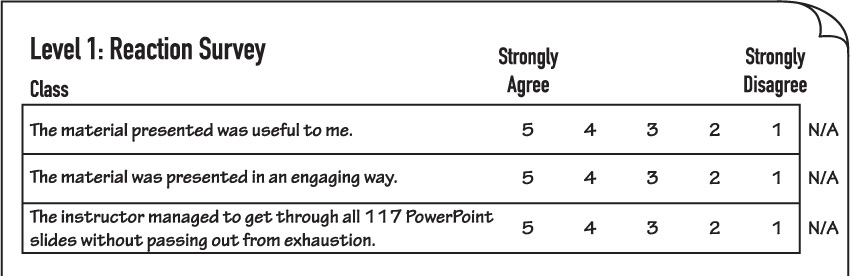

If you’ve studied instructional design, you are probably familiar with the Kirkpatrick levels of evaluation. Level 1 evaluation is “Reaction—To what degree participants react favorably to the training” (Kirkpatrick 2015).

Frequently, it gets measured with something like this:

I have no problem with asking people after the class/course/resource whether they liked it. Sure, why not ask? This is probably the single most common form of evaluation for adult learners, because (like multiple-choice questions) it’s the easiest and quickest to do.

If you choose to measure reaction, here are a few things you should consider:

• This data tends to be collected after the whole learning resource has been completed, proofread, checked, and polished. This means that it’s really hard to go back and change things that aren’t working. If you can get reactions (along with user testing results) earlier in the development process, you are much more likely to be able to correct things before it gets too far.

• Try to keep it short. I’ve noticed a trend toward shorter customer satisfactions surveys (one to three questions), to which I can only say hallelujah! Try to keep yourself to no more than four questions, and have at least one question be an open-ended text field in which people can write their own feedback.

• Recognize the limitations. This kind of survey will most likely alert you to problems. If your audience is unhappy, you probably need to take action. What this type of survey will not do is tell if you things are really working. You could get positive responses because people didn’t really understand, or because they wanted to be nice, or because you asked the question in just the right way. There are ways to maximize the efficacy of reaction surveys (Thalheimer 2015), but to really understand whether the learning experience is effective, we need to look at other measures.

Are They Learning?

There are whole books on the topic of test construction, and I won’t be able to address all the issues with measuring learning, but I want to discuss a few considerations.

Recognition Versus Recall

We discussed the issue of recognition versus recall in Chapter 4, but it’s worth discussing here too.

Take a look at this question. What do you think the right answer is?

You have an angry customer demanding that you reverse a charge on her account, but you don’t have the authority to do so.

What do you say?

A) “I’m sorry ma’am, but that’s the policy.”

B) “Only a manager can do that.”

C) “Ma’am, I understand why you would be upset about an incorrect charge.”

D) “Of course we’ll take care of that right away!”

You don’t have to know all that much about customer service to figure out that answers A and B will cause customer rage and that D is just wrong.

So if a learner answers this question correctly, what does that tell you about what they learned? It tells you that they can apply basic logic to a situation, but it tells you very little about their customer service knowledge.

Recognition isn’t a bad thing, and it’s often a necessary first step in understanding a topic, but it only gets you so far.

A recall-based question would be much better.

You have an angry customer demanding that you reverse a charge on her account, but you don’t have the authority to do so.

What do you say? (Write your answer in the space provided.)

The problem with recall questions is that a human has to look at them to judge whether the answers are right or wrong, which is a much more labor-intensive process than letting a computer grade the choice of A, B, C, or D.

If learners need to recall their answers in the real world, you should use recall-based assessment whenever you can, but sometimes it’s just not an option. Sometimes, the only available tool in your toolbox is recognition-based assessment. How can you use it most effectively?

There are ways to make recognition questions better:

• Make them scenario-based. If the questions are part of a bigger, context-rich scenario based on the real dilemmas people face on the job, then right answers will often be more challenging to identify, and learners will have context cues that will help them transfer the idea to their work environments.

• Have lots of options. This is a fairly blunt solution, but if you are asking a question about what particular tool a repair person should use to replace the solenoid valve on a dishwashing machine, they will have to think more critically to select it from a visual showing all the standard tools in their toolbox, rather than selecting one answer from a list of four in a multiple-choice question.

• Don’t use wrong answers. The format for multiple-choice questions is typically one right answer and two or three wrong answers. But if the choices are one pretty good answer, one semi-mediocre answer, one great answer, and one OK answer, then finding the best answer becomes much more challenging. It can be very difficult to write one plausible distractor (wrong answer). Writing three plausible distractors is sometimes just not possible. You can also weight answers—for example, a really good answer could be worth 10 points, but an OK answer might only be worth 3 points.

So Recognition Can Work?

Recognition-based testing is still a limited format, and it really only works well for knowledge-based gaps. If your learning objectives are all about salespeople knowing the right answers to customer product questions, it’s not too difficult to figure out how to use recognition-based test questions to assess that. Recall or performance are probably still better options, though, particularly when we start to assess skills. We’ll talk about performance feedback next.

Can the Learners Actually Do the Right Things?

If you are assessing a learner’s ability to recall or generate answers, or their ability to perform a skill, you need assessment that has them perform. Their performance should then be evaluated.

Basically, you need to do these two things:

• Have the learner perform the task.

• Give them useful feedback.

That’s it.

OK, it’s a little more complicated than that, but that should be the heart of most learning assessment.

So what are the issues? Well, first you need to figure out who will be providing the feedback, and next you will need to figure out how to make sure that the feedback is valuable and consistent.

Providing Feedback

If the popularity of recognition-based evaluation is because feedback is easy and consistent, the challenge of recall evaluation is that feedback can be difficult and inconsistent.

The more complex the performance, the less likely that there is a single “right” answer, which means that evaluating can’t be handled by a computer or a testing assistant with an answer key. Instead, you have to have a human being who can read or watch the performance and give meaningful feedback.

And your evaluators need to have sufficient expertise not only in the subject area but also in evaluating and providing feedback. I might know how to play tennis, but that doesn’t mean I know how to evaluate tennis performance in others or how to communicate that feedback in a clear and useful way.

If it’s too costly to have an expert reviewer, some possible alternatives include:

• Peer-to-peer feedback. When there aren’t sufficient expert resources, it can be possible to arrange for students to give each other feedback. It obviously depends on the task being performed. Some of the online language platforms have used this to help students get feedback on their pronunciation. If I’m an English speaker who wants to learn Lithuanian, I can help a Chinese speaker with her English pronunciation, and in turn I can get help from a Lithuanian student who is using the platform to learn English.

• Near-peer feedback. While my tennis skills definitely don’t qualify me to give expert-level feedback, my intermediate-level skills could probably enable me to give reasonable feedback to very novice tennis players, particularly if I were given specific guidelines by an expert instructor (e.g.,”Don’t let the racket come up above the elbow”).

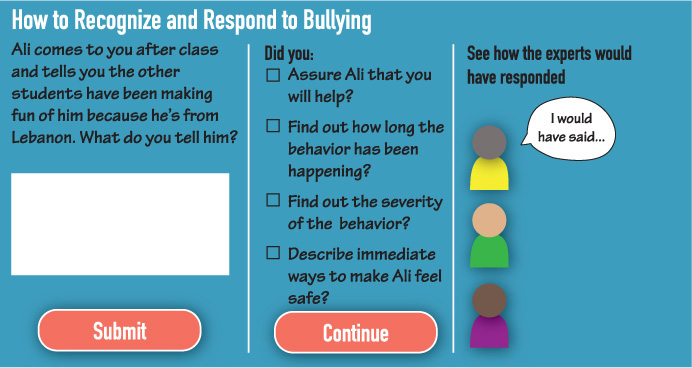

• Self-evaluation. You can create opportunities for the learner to self-evaluate by giving them criteria, reflection questions, or examples that they can compare their performance to. I’ve used the following format in elearning courses when it wasn’t possible to provide human feedback:

The learner enters their own response and then submits it to see the checklist and self-evaluate. Next, the learner can click Continue to see the expert versions.

Consistency

The other issue, of course, is consistency. The more subjective the performance is, the more that the feedback will be in the eye of the beholder.

So if you have human evaluators giving subjective feedback, how do you ensure that there’s consistency? Even if all the feedback is coming from the same person, consistency can be an issue. One study found that judges give harsher sentences right before lunch than they do earlier in the day (Danziger 2011), and it’s not possible for a grader to remember exactly what logic they used on the first paper when they are grading the forty-first paper.

Tools that you can use to create feedback consistency include checklists and rubrics.

A checklist can be a consistent set of steps or items in a task, or a set of criteria that the learner needs to meet. For example, if you want to evaluate whether or not a new housekeeping staff member has adequately learned to clean hotel rooms, you will give much better feedback if you have a checklist of all the required steps with performance criteria (e.g., “Wiped mirror, leaving streak-free”).

A rubric can have the same items, but it will also usually have specific rating criteria to help improve the consistency of scoring. The self-assessment for time management in Chapter 9 is an example of a rubric. Rubrics are frequently developed to make the performance of tacit skills more explicit, as we saw in the Chapter 9 section on designing for habits.

Let’s take a look at an example. Think about how you might assess this situation:

Use Your Objectives

If you’ve used the criteria from Chapter 2 for developing learning objectives (would it happen in the real world, and can you tell if they’ve done it), then those learning objectives should point directly to the performance required for evaluation.

Let’s look at a few of those objectives:

• Learner should be able to identify all the criteria necessary to select the correct product for the client.

• Learner should be able to create a website that works on the five most common browsers.

• Learner should be able to identify whether a complaint meets the definition of sexual harassment, and state the reasons why.

The performance for each one of these is spelled out in the learning objectives, though you still have to determine how you will evaluate that performance.

One trick that experienced learning designers use is to create the evaluation before building the learning experience so that they have a clear road map for the learning design.

Are the Learners Actually Doing the Right Things?

Now that we’ve talked about some of the issues in evaluating learning and ability (roughly Kirkpatrick Level 2, for those keeping track), we get to our last and most important question.

Are the learners actually doing the right things when they go back to the real world?

In my experience, this tends to be the least measured element in adult learning. It’s not hard to understand why. Figuring this out can be a costly undertaking if your organization isn’t already collecting performance metrics.

If your organization does regularly collect metrics, this isn’t so bad. Let’s say you are creating a training on how to sell water softeners for your commercial plumbing service. You probably know how many water softeners were sold in May. If you roll the training out at the beginning of June and sales double, you can be pretty confident that the training accomplished something.

If you want to be sure that it isn’t due to some other variable (a groundbreaking exposé on the tragedy of hard water, or the rollout of a supernewshiny water softener), you can do A/B testing. To do that, you split your sales force in half (groups A and B) and have only group A take the training. If group A outperforms group B, then you have good reason to believe the training was effective. If the training was effective, you can roll out the training to group B after the test period.

But what if your organization isn’t already collecting those metrics? For example, what if you are creating a course to help managers get better at feedback, but there are no manager-effectiveness measures in place? Or what if you don’t have that much access to learners after they go back to the real world, like the students in the public workshop on how to conduct usability tests?

There are two strategies you can look at:

• Observation

• Success cases

Observation

If you lack organizational metrics, direct observation is probably the most effective method. If you do a training that emphasizes wearing safety glasses on the shop floor, then you should go down to the shop floor and count the number of people wearing safety glasses before and after the training.

But what about our manager feedback example? That’s not quite so visible and, therefore, not quite so easy to count. How can we measure whether or not that’s happening in the world?

One option is to use the checklists or rubrics you created for evaluation, and modify them for use by either the learners’ supervisors or the learners themselves. Supervisors often want to help develop their people, but they are busy, and a format that makes it relatively easy for them to do observation and feedback can sometimes make a real difference.

If observation of the entire population just isn’t practical, cohort observation could be an option. If you are training 12,000 nurses how to use a piece of medical technology, it’s probably impossible to observe the whole population, but you could observe two or three groups of 20 nurses and use that data to inform your practice.

You can look for other signals that may indicate whether the training is effective. For example, would employee retention be better if managers were better at giving feedback? Would there be fewer calls to the help desk if the new hire training for service techs were successful? Would the rates of infection go down if the handwashing training were successful?

I saw a presentation a few years ago in which the training department attached Google Analytics to their internal help and support pages so that they could tell which pages were accessed frequently and which had never been accessed. While this wasn’t conclusive proof of efficacy, it did help them understand the impact they were having.

Qualitative Interviews and Case Studies

So if these methods sound great but ultimately aren’t practical for your situation, interviews and case studies could be feasible methods.

Basically, can you call up a half dozen of your learners four to six weeks after the learning event and talk to them about what is working and not working? If you get them to tell you stories about application, you can learn much more from the conversation than you can from a survey or a test score.

If you need a more formalized approach, the Success Case Method, by Robert Brinkerhoff, is a good option. Essentially, the steps are:

• Determine what the impact of the learning should be for the organization.

• Send out a very short survey a short time after the training to identify who is using the learned material and who is not.

• Conduct interviews with a handful of the most successful and least successful users.

If you have the email addresses of your attendees, you can follow up using this method regardless of the circumstances. Even if you talk to only a half dozen of your learners, the information will be invaluable. There is more detail about implementing this method in Brinkerhoff’s book The Success Case Method.

The crucial piece is to figure out how to get feedback into your own learning design practice. How do you know that what you are doing is effective? Some of it probably isn’t, but if you don’t have feedback coming back into the system, you’ll never be sure what is working and what isn’t.

Summary

Summary

• Test your learning on a few users ahead of time so you can smooth out the rough edges before it goes out to your entire population.

• Use recall- or performance-based assessment whenever you can.

• Surveys can give you useful information, but keep them short and give learners some space to write their own responses about what worked and what didn’t. Surveys probably shouldn’t be your only form of evaluation.

• If you use multiple-choice testing, try to use scenario-based questions that require your learners to apply what they’ve learned.

• Have people perform, and give them feedback.

• Peer evaluation or self-evaluation can also provide useful feedback.

• Use checklists or rubrics to make feedback more useful and consistent.

• Observation and interviews can provide feedback to you as the designer about what is and is not working in the learning experience.

• Look for the signals in your organization (e.g., the number of customer service calls) that can give you an idea of whether things are changing.

References

Brinkerhoff, Robert O. 2003. The Success Case Method: Find Out Quickly What’s Working and What’s Not. Berrett-Koehler.

Danziger, Shai, Jonathan Levav and Liora Avnaim-Pesso. “Extraneous Factors in Judicial Decisions.” PNAS April 26, 2011. 108 (17).

New World Kirkpatrick Model. Retrieved October 13, 2015, from www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/OurPhilosophy/TheNewWorldKirkpatrickModel/tabid/303.

Thalheimer, Will. 2015. “Performance-Focused Smile Sheets: A Radical Rethinking of a Dangerous Art Form.” www.SmileSheets.com.